A rollicking krimi with a pair of mismatched buddies, one an extroverted sleek lowlife car-thief with a four letter-word vocabulary and the other an introverted roly-poly PhD scientist in Cologne Germany.

Pascha is a rev head who loves cars, and stealing them is great fun, the more so getting paid to do so. Then one night after stealing a particularly desirable rocket car, on order from the Russian mafia, he finds in it…. Something he should not have.

He pays for his discovery and that brings him into contact with Martin, the super nerd. Their efforts to communicate and, reluctantly, to cooperate are a hoot. One is street wise to the Nth degree and the other equally book wise.

With false starts, snits, and pouts they slowly combine to find a killer, and find both more and less than they bargained for. Along the way they come to respect the assets each brings to the mission. The setting of Cologne, that cathedral city in Germany, offers much to’ing and fro’ing around town. There is some travelogue as each shows the other his haunts.

It is hard to say more without a very large spoiler.

This is the first in a series and I hope the author can keep up the joie de vie.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘Mannerheim: The Finnish Years’ (2014) by J.E. O. Screen

This is the completion of an excellent biography of a singular military and political leader.

When Finland created itself in 1917, Mannerheim was the man of the hour.

From the summer of 1917 to 1919 Finland was a land, with ill-defined borders, of conflict. In the textbook history, there were two overlapping wars. The Independence (sometimes Liberation) War to drive the Russians, be they Czarists or Bolsheviks, of Finland, and a Civil War between Red Finns and White Finns. These two conflicts overlapped and intwined.

White Russians wanted aid from White Finns in their own civil war in Russia, and Red Finns wanted help from the Bolsheviks in Russia in their struggles in Finland.

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia.

Greater Finland, some maps also include Estonia in this national ambition in the same way that some maps in Jakarta include all of New Guinea island as part of a Greater Indonesia.

Both the Western Allies and Germany, even while at war with each other, wanted to stem the spread of Bolshevism. But the Allies did not want the Germans gaining influence in Finland. Mannerheim tried to get support from the Western Allies, but they were in no position to offer material aid in 1917.

The criss-crossing of these aspirations and allegiances is detailed in the book in a concise and lucid way. Some of the belligerents stuck to their position regardless of reality.

Mannerheim changed with the times, slowly and reluctantly, but change he did.

He did try to negotiate with White Russians on joint action to drive the Bolsheviks out St Petersburg, as he always called it, in return for which the White Russians would acknowledge Finnish sovereignty. The White Russians refused to countenance Finnish autonomy. They stuck to their guns and went down.

North is white and south is red.

North is white and south is red.

He created a Finnish Army that disarmed and expelled the Czarist garrisons in Finland, some thirty thousand of them, closed the border against the Bolsheviks, and defeated the Red Finns in a civil war by systemic and methodical action. The Red Finns had dominated Helsinki and southern Finland.

The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners.

The caption says it is White solders murdering Red prisoners.

The Finnish Council wanted a speedy resolution and appealed to Germany for help, which was offered and German troops, freed from the Eastern Front by the collapse of the Czarist regime, though a state of war continued between German and Russia, were sent to Finland. This was presented to Mannerheim as a fait accompli, and he grizzled at it. He stressed that Finland had to be created by Finns, though he said that in Swedish. He also insisted that the Germans play only a supporting role.

Instead it was the Germans who defeated the Red Finns in Helsinki, and this outraged Mannerheim, but he swallowed it. It was a done deal, though it left a long and bitter aftertaste.

Then another comic opera ensued. Finland now had to have a constitution, and the self-appointed leaders decided on a monarchy and in early 1918 invited a German prince from Hesse to be king of Finland. He dickered on terms in great detail about everything from regalia, to aide-de-camps, to caviar so long that, well the German Western Front collapsed, and even the most stubborn Finns realised setting up a German in Helsinki was not a good idea. If the Prince of Hesse had not stuck to his guns he might have slipped in a Finnish throne before the fall.

For about eighteen months as the Civil War wound down, and while a new constitution was formed and then changed, the Finnish Council named Mannerhiem Regent. He was at once Commander-in-Chief of the armed force and head of state. He got the Germans out and spent a lot of time courting the Western Allies.

The war made Mannerheim a Finn as never before, but it also made him a White Finn in the eyes of Red Finns and their sympathisers and supporters in their defeat. He was polarising, even divisive figure. That would change.

The revised constitution called for a President and a Prime Minister on the French model. The President elected and the Prime Minister the leader of a majority in the parliament. How then to elect the president. It was common for such officials to be elected by the legislature, The alternative was direct popular election. No one doubted that Mannerheim would win a popular election.

But he had many enemies in the parliament. The Agrarians of the right thought him Russian in disguise. The Liberals of the centre thought he was a Swedish coloniser. The few remaining socialists of the left hatred him because of the Civil War. The Conservatives suspected he would be a dictator. He would not win election in a parliamentary vote.

Mannerheim recognised the election of the first president in the new, sovereign constitution was a very important event for the future harmony and stability of the country and so in the interest of stability he accepted a parliamentary vote without argument. In due course, he was a candidate and lost decisively. Think of Churchill in July 1945 losing.

From 1920 to 1932 he was a private citizen, if a former supreme commander and head of state can be that. He traveled in Europe and became an unofficial representative of Finland, much to the annoyance of the foreign minister in Helsinki. His aim was to affirm Finland’s sovereignty, and win it friends and support in Western Europe against the tides of the future.

In Finland he remained a popular figure in the public mind, apart from socialists; his political enemies, the full spectrum from left to right, blackened his name at any and all opportunities. This was another reason to travel abroad.

Thanks to the influence of his sister, Sophie, when he retuned to Helsinki, he threw himself into good works and became president of the Finnish Red Cross where he was not content to be a figurehead on the letterhead. Instead he developed training and recruitment. He also strove to raise money and succeeded.

Then in the 1930s the political leadership realised that the League of Nations’ collective security would not protect Finland from the predators, especially the Soviet Union which had reactivated the Czarists claims to the whole country. Mannerheim was made chief of defence in a convoluted arrangement that was neither military nor political, but a little of both. In effect, he was chairman of a defence advisory committee. He was appointed head of the national militia, not the army. There followed another comic opera.

Was he entitled to a uniform? If so what kind? When could he wear it? And so and on. All of this had to be decided by a committee. He wanted symbols of office and others wanted to deny him those appurtenances. Meanwhile, the Soviets built roads to the border, dredged anchorages on the coastal approaches to Finland, flew over Finnish air space to photograph the ground, and so on, while in Helsinki they argued about tailoring. And to the south Hitler was arming Germany with bellicose claims about the oneness of Nordic peoples and threats to Danzig on the Baltic. While in Helsinki they argued about tailoring.

The impasse was broken when the national militia declared Mannerheim an honourary field marshal and presented him with a baton of command. This presentation was widely publicised because Mannerheim had learned to use the press, while his enemies had not. In the end, the parliament, begrudgingly, made him a field marshal of the regular army. But he only and always carried the first baton bestowed on him by soldiers, not parliamentarians.

He became a one-man lobby for increased defence spending, conscription, training, fortifications, aircraft, warships, a medical corps, and so on. He invited newspaper editors to dinners and argued his case with them. He also tried hard to secure an alliance with England and France and when that receded, he then tried for a Nordic defence pact but Sweden would not jeopardise its neutrality, on the assumption that the Russian bear would be content to eat Finland.

He also made an effort to learn Finnish. He had dabbled at this for years without systematic application. He selected two aide-de-camps who spoke only Finnish, and that meant he had to speak Finnish to them, to get a file, to get a match for a cigarette, to bring the car around for trip, to telephone newspaper editors…… He also hired a tutor who worked with him an hour every night. Then there were small dinner parties of four or five Finnish-speakers. These were not business meetings, not were they pleasure, but rather language practica. When this man decided to do something, he did it. In a few years he could speak enough Finnish to give speeches broadcast on radio, and read it, but he could never quite write it properly and retained an assistant especially for that purpose.

When he began inspecting troops, and interviewing field officers, he had cue cards in his pockets to remind himself what to say and how to say it.

Even in 1938 there were parliamentarians who assumed there would be no war that would involve Finland. Wrong! The Baltic Sea would be a prime battleground as Mannerheim saw it. That is one reason why he courted England with the Royal Navy.

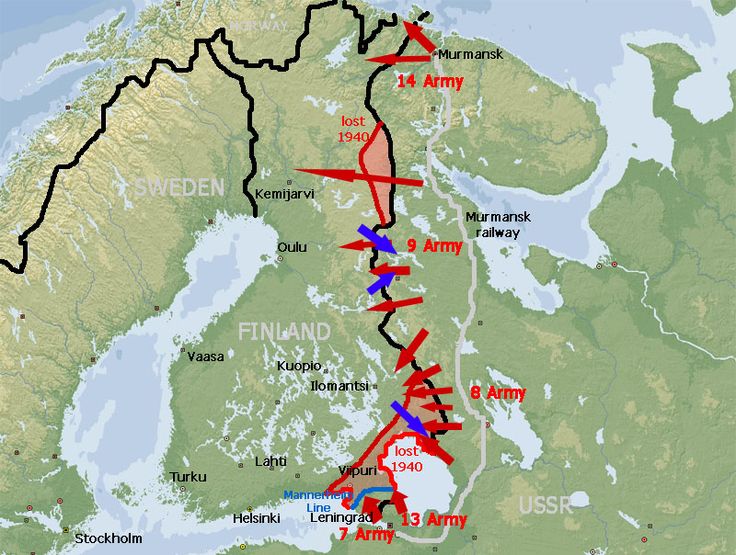

The Soviet offensive.

The Soviet offensive.

Perhaps Mannheim’s most decisive achievement before the Winter War was to change the method of mobilisation. Instead of gathering troops at a few central points, arming them, and then transporting them to the front he changed the locus of organisation to many local levels and distributed the arms and accoutrements of war to warehouses throughout the east parts of the county. Mobilisation would them involve much less transportation, though it dispersed control.

When the Soviet attacked, Finns responded much more quickly thanks to this dispersal of men and armaments. It also left much more leeway for local commanders to use their own judgement, which many did to good effect. He had also implemented a training program for these local commanders to learn the best exercise of that judgement.

Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden.

Finnish troops using reindeer as beasts of burden.

Though Mannerheim knew that details mattered, he never seems to have been a micro-manager.

The Winter War started in November 1939 while Germany and the Soviet Union were dividing up Poland. The Soviets had strategic and historic reasons to attack and they arranged a pretext, taking a page from Hitler’s Poland book. In the first phrase about 400.000 Soviet troops attacked about 150,000 Finns.

The Soviets were better equipped and that became a liability. their heavy tanks and trucks had to use roads through the forests or cross frozen waters. The Finns used those passages as choke points. Most of the Soviet effort was around Leningrad but there was also a strike above the Arctic Circle. This first Soviet offensive failed with terrible losses.

Stalin reacted as Stalin did. He murdered scores of Soviet generals, and formed a new offensive on an even larger scale. Soviet manpower in the army was unlimited compared to Finland. The second offensive included 600,000 troops.

The Finns resisted along the so-called Mannerheim Line in the South. It was nothing like the Maginot Line, representing the places where geography favoured the Finnish defence in the forests and lakes. Elsewhere the white-clad Finns concentrated on behind the lines raids to harass, slow, and deflect the invaders.

Resistance was futile, and many efforts to secure weapons and support from the West and Scandinavia failed. The Soviets offered negotiations, perhaps realising that to vanquish Finland might lead to a military clash with either Germany in Norway, or even the Western Allies.

Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944.

Field Marshall Mannheim at his desk in early 1944.

Mannerheim strove to hold onto Finnish territory until spring thaws would clog roads and melt ice, which together would immobilise the Soviets. The spring was late, and the Treaty of Moscow was concluded in April 1940 on very hard terms. Perhaps 20% of Finland would annexed by the victors, and its population relocated to the rump of Finland. Financial reparations were exacted, paid for mostly by metals and minerals and control of Baltic islands. This might well have been the first bite, with another to follow.

A kind of peace ensued. Mannerheim had been made Commander-in-Chief of all arms during the war and that authority rolled on. His sway with the parliament was great now, because so many of them had been discredited for supposing no war would come, for cutting defence budgets, for not denouncing the Soviet Union earlier enough and loud enough, and for fleeing while the army fought on.

The Finnish national day had been heretofore the day that marked that the end of civil war. To the Reds of Finland that was a day of ignominy. Mannerheim changed the national day to coincide with the defeat in the Winter War. He saw in the months of the Winter War, as did nearly all others, one Finland, neither White nor Red.

If Finland made itself a geo-political entity — a state — in 1917, in 1940 the Soviet made Finland socially into one people — a nation.

From mid-1940, as World War II unfolded, Mannerheim assumed that the two colossi would clash and the Finland would be in the middle. While he did not favour an alliance with Germany, which was on offer, there would now never be any reconciliation with the Soviet Union. The Western Allies were too far away, and France was out of the war, and could not be counted on for support.

Once again he prepared Finland for the next war. Only locally made equipment could be had, but the army was doubled in size.

In the weeks before Operation Barbarossa, the Germans made demands on Finland for passage from far northern Norway to Russia, and the Finns agreed.

The Germans were so intent on practical matters, that they did not press the Finns for a formal alliance. The Finns, for their part, agreed to fight the Soviet, but only if the Soviet first attacked Finland. When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, the Finns held their positions and waited. Sure enough a few days in the battle and the Soviets began bombing and shelling Finnish territory and the Finns became co-belligerants.

It is a technical point that later was of paramount importance.

The Germans had offered Mannerheim supreme command of all troops in Finland, German and Finn. He declined. That would have brought 250,000 German combat troops from the Arctic Circle to the Baltic Sea under his command, along with the 650,000 Finns in uniform. However that would also have made him subordinate of German High Command in Berlin, and he wanted scope to act independently in the interest of Finland, not as ordered from Berlin.

As much as 20% of the Finnish population was in uniform, including scores of thousands of women. It was prodigious national effort that could not be sustained long.

His prudence also meant that he directed the Finnish war effort at strategic targets rather than symbolic ones. Ergo the Finnish advances cut-off Leningrad from the north but did not directly attack Leningrad. Another fine point that later proved crucial. He assumed no subsequent government in Russia would forgive or forget an attack on that city so the Finns would not attack it.

To stress the Finnish nature of the conflict, Finns called it the Continuation War, the war that continued the Winter War. Every effort was made to keep it separate from the German war so that Finnish interest were seen as separate. Finland was divided into a northern and southern zones and the Germans in Lapland had the north. That meant that when the Germans attacked in the north the Finns did not support it. Rather they held their defensive positions much to the outrage of the Germans.

It was widely assumed in 1941 that Germany would knock the Soviet Union out of the war just as it had done in 1917, either directly or by precipitating a regime change.

The Finns in the south advanced to the 1939 border and stopped there and remained on the defensive. In the north the Germans were unable to cut the Murmansk railroad, and that failure registered with Mannerheim. The stout Soviet defence of Murmansk and the railroad led him to conclude that the Soviet regime would not be knocked out, nor would the regime topple.

Thereafter the prospect of a separate peace with the Soviet Union was discussed among Finns.

Hitler wanted to draw Finland closer as his Soviet invasion faltered, and a Fuhrer-visit was proposed.

Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods.

Hitler and Mannerheim deep in the north woods.

Mannerhein advised the government against it, and himself stalled. Finally it was agreed that Hitler would attend Mannerheim’s 75th birthday lunch. On the grounds that he could not leave the front, this was held in a forest in east Finland with few guests and no media, apart from the offical photographers.

Instead of state visit in Helsinki with parades, flowers, presentations, speeches there was a two-hour lunch followed by coffee with a few candid photographs.

Inevitably, as we now know, the Soviet Union attacked Finland in 1944 with a numerical advantage of ten to one, and the front crumbled. The Finns fell back to the second line, to the third line…. Mannerheim told the government that one more push from the Soviets and it was over.

However, the push did not come. Instead Soviet troops transferred south to concentrate on the advance on Germany, while Finland imploded.

Any effort at a separate peace would invite German retaliation, but with no separate peace the Soviets would sooner or later attack again. To walk this fine line the parliamentarians, who were on a carousel by this time, changing governments weekly, proposed uniting civil and military power in Mannerheim. He declined several times but finally agreed and the parliament made him president while he retained the role of commander-in-chief of the armed forces and Marshal of Finland. The feeling was that only Mannerheim had the domestic moral authority to convince the populace to comply but not to lose hope. That only he had the authority to convince the Germans that Finland was serious about leaving war, and the Soviets that it would honour an agreement.

He set about securing a separate peace and preparing for conflict with the Germans. While Finland was a co-belligerent, Germany had been supplying much fuel, war material, and food. Once the rumour of a separate peace circulated these supplies stopped. In anticipation of just such a reaction Mannerheim had been stockpiling supplies for about a month beforehand.

The Soviet demands were territorial, financial, and moral. They wanted back east Karelia and to move the boundary on the Karelian isthmus north, huge reparations, and a treaty of friendship of the kind it had had with Estonia. (Gulp!) The Finns conceded the territory and the reparations but bargained away the treaty in favour of guarantees of neutrality. It was a return to the 1940 post-Winter War borders with a financial burden on top.

It may seem to have been wasted effort, but there was no third way for Finland. Had it not entered the war, the Soviets would likely have occupied the whole country to control the Baltic, and stayed. Sweden was far enough away to be neutral, but Finland was not. Had the Finns not entered the war, the Germans might have occupied the whole country and set up a puppet regime as it had done elsewhere, and used Finnish resources for German ends.

Finland was the only associate of either German or the Soviet Union to keep its independence and to continue its internal way of life, e.g., parliamentary democracy and religious freedom. Despite pressure Jews were not deported. Indeed Mannheim attended a memorial in a synagogue in Helsinki for fallen Jewish soldiers in the Finnish army, a fact reported in the local press.

In addition to the other terms, the Soviets also wanted the Finns to expel the German army in the North, some 250,000 Alpine troops around the Arctic Circle besieging Murmansk. This led to another conflict, called in Finnish history, the Lapland War. The exhausted, defeated, undermanned, ill-equipped Finnish army turned north to push the Germans back into Norway at the behest of the Soviets. While this was a low level conflict compared to what was going on elsewhere, another one thousand Finnish soldiers were killed.

This tumultuous period in sum:

Winter War April 1939 – May 1940

Interim Peace 1940 – 1941

Continuation War June 1941 – April 1944

Moscow truce 1944 ended Continuation War

Lapland War April 1944 – May 1945

Peace 1945

The War of Liberation, the War of Independence, the Finnish Civil War 1917-1919 made the geographic entity Finland. However it was the Winter War together with the Continuation War that made Finns into a single people. The national unity, especially in the Continuation War was palpable, and Mannerheim did everything he could to nurture and encourage it. He ended the celebrations and symbols of the Civil War, and created instead public holidays, awards, and recognition for contributions to these two later wars with the Soviet Union.

With the end of the Continuation War a Soviet Control Commission set up in Helsinki and intervened deeply into Finnish politics, society, and economy, but not as deeply as in the Baltic, eastern, or central Europe. There was no puppet government and sometimes negotiation was possible. But parliamentary candidates, court appointments, factory rebuilding, and more all had to be approved by the Soviet Control Commission, which in turn referred decisions to Moscow. The Soviets ensured that Finland did not receive aid from the Marshall Plan.

In 1948 many Finns, including Mannerheim assumed a communist putsch would occur in Helsinki as it had in Prague. He burned many archival papers at the time, and army officers cached weapons in anticipation of another, guerrilla war.

Mannerheim resigned as domestic politics went back to the old ways of backstabbing and undermining, much of it encouraged by the Soviet Control Commission which preferred disunity. His health was deteriorating and he spent time in Portugal and Switzerland, where he secretly worked on his memoirs. In the memoirs he tried to set the record straight, as he recalled it.

He died in 1951 at age 84. Even in death he polarised the society. Some wanted a state funeral and others opposed it, believe it or not. The army pretty much forced the issue and it was a state funeral which was boycotted by the communists in parliament.

Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

Equestrian statue of Mannerheim in Helsinki.

On 5 December 2004, Mannerheim was voted the greatest Finnish person of all time in the Suuret suomalaiset (Great Finns) contest.

There were twenty years between the first and second volume, yet the level of analysis, handling of sources, expression are continuous. Well done.

The book is a model of economy, presenting vast amounts of information in a few pages. Would the other authors would do likewise. This volume is a mere 250 pages but each is fully loaded.

‘Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey’ (1991) by Brian Urquhart

Heads up! Who was Ralph Bunche (1903-1971), and why do not you know? You do not know, now do you. Shame!

A few hints then. He was point guard on three conference championship basketball teams at UCLA. [Sounds of silence.] This was a minor part of his odyssey.

Another hint. He had a Harvard PhD in political science.

No, still nothing.

How about the fact that he got a Nobel Peace Prize, and in his case, unlike several other recent recipients, it was deserved.

A last try, he served in the OSS during World War II. Huh? I hear the thinking. Look it up, Mortimer.

Let’s get the cat out of the bag. He was Dag Hammarskjöld’s right hand at the United Nations where he worked from 1944 to 1970. In fact, his tenure preceded Hammarskjöld’s and, of course, he outlived the Swede.

Oh, and he was an American Negro (the term he always used). That bespeaks the odyssey. His grandparents were born in the slave society of Missouri.

It was an article of faith from those grandparents onward on both side of the family tree that a black had to be educated to survive in the white man’s world.

Born in a Detroit before it became the manufacturing capital of the United States, his family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico in the early 1915. Tuberculous was suspected in some family members and they packed off for the dry climate with a few dollars and strong wills to make a living. His mother and grandmother combined to insure that he got an education. When his school work was poor they complained to the school, where the principal rather thought they should be grateful that the school even took in a negro.

He was a bored student in high school, these two decided, because the school had slated him for vocational classes, woodwork, typing, auto shop, book-keeping. They more or less sat in the principal’s office until Bunche was put into the academic track of college preparation. They then applied themselves to making sure Ralph lived up to the challenge, and he did.

He encountered racism but only small doses in the sparsely populated New Mexico. The family moved to Los Angeles, as so many others had, to find the land of milk and honey, after the arid dust of the south west. He graduated from high school first in his class but was not recognised as such. Figure it out!

Yes, he played sports as boys do, and got a scholarship to play basketball at Cal.

Sportsman.

Sportsman.

Like many others he combined the gym with the library.

He was first in his class again but not honoured as such…because? See if you can guess. The school did not want a black face at the podium with all those benefactors and check books present.

The BA was not enough. He did the one true major, political science. His undergraduate supervisor encouraged him to do graduate work and he went to Harvard, first for an MA, and then a PhD. Along the way he had many part time jobs as students do, and each time he did his best to do them well. He knew that there was no margin of error for a black man.

The PhD made the man for he studied European colonialism. To do that his supervisor insisted he learn languages, French and German. His supervisor also secured funding for him to do fieldwork in European archives and in west Africa. Young, energetic, idealistic, and black he examined French colonialism in west African colonies some of which had been German. What impressed most him the most in his contemporary letters was the alcohol that French colonial officials put away. Second, was how sloppy the records in the archives in Paris were. Third, he found virtually no racism directed at himself in Paris, Dahomey, or Togo. At the time, he took it for granted but in latter life mused on the two-speeds of racism.

Howard University in Washington, D.C., a black college, created a political science department and appointed him the foundation professor and head of department while he was completing the PhD research. He was appointed ABD!

ABD? I was appointed ABD at Sydney. These days few people would be appointed ABD. ABD? All but dissertation. It means that a graduate student has completed all the requirement for the PhD but has not yet submitted the dissertation and had it accepted.

After a master degree with a thesis, the PhD requirements would include three years of advanced seminar work with many essays and research projects, then general written examinations (in three fields), and oral examinations over the generals. It would also include the preparation, defence in writing and oral tests of a proposal for the PhD dissertation. It is heavy lifting. But the heaviest lift is to come in the dissertation which takes about two more years.

But there are many stops along the way from ABD to completing the dissertation. ABD forms a continuum. At one end is as above, at the other is someone who completed all the research, written the dissertation and had it examined and passed, but the degree has not yet been awarded due to the cycle of the university.

To cut to the chase, many, many ABDs do not become PhDs. They do not complete that final requirement, the dissertation and defend it. Of these most just do not finish; only a few finish the dissertation but fail the final defence, though I have seen it happen twice in my forty years at the table.

There are as many reasons why ABDs do not finish as there are ABDs. Life intrudes, the fellowship runs out and a living has to be earned. Pregnancy alters priorities. It proves hard to conceive, execute, and write a book in the two years.

While ABD Ralph Bunche had his share of problems. His duties at Howard were demanding. and while the pay was adequate there was nothing left for more field-trips, to pay for professional typing, conference travel, or translations. But somehow, thanks largely to his long suffering wife, Ruth, he did it. In sum, he had all the problems any ABD had, and each was overlaid by the racism of the time and place. e. g., getting access to the Library of Congress was a struggle for a black man.

He got another fellowship for archival research, this time at the Colonial and Foreign Office in London and during this period he met a long list of others like Paul Robson, many of them communists to a degree, as the only recourse for black hopes. He found himself at home in this worldly milieu, but argued constantly against the communist line. He agreed that class incorporates race and was the origin of much racially suspicion, fear, and hostility in the white working class and lumpenproletariat, but he had no use for the Communist Party as an agent of change for the better. Of course merely talking to such believers made him a fellow traveller to the likes of Hoover J. Edgar. During this period, 1937-1938, he made an extensive field-trip to East Africa, including Kenya, where he made many contacts thanks to his London friend, Jomo Kenyatta.

When lights went out all over Europe again, the War Department began serous recruiting, and it wanted an African specialist, especially French North Africa. Bunche was recruited to work in that very same Library of Congress. Cognoscenti will know that the OSS was housed there initially because Colonel William Donovan wanted his agents to have a thorough grounding in culture, history, and languages. Yes, Bunche became a desk officer for the Office of Special Services, the parent of the CIA. He wrote manuals and training programs that were eventually used by American forces in Operation Torch, the landings in Morocco and Algeria.

He also attended at least one of the Roosevelt-Churchill summits which addressed the post-war world. President Roosevelt wanted planning for the post-war world to start from day one of the war, or before, and it was in fact before, because he had seen the aftermath of World War I descend into comedy, farce, and now tragedy.

When the idea of a new League of Nations to keep the peace emerged, the State Department wrenched Bunche from the OSS and put him to work on the future of colonial places and peoples. Bunche had become the United States expert on European colonies. He attended the San Francisco foundation of the United Nations on the American delegation, where he soon became the United Nations expert on colonies.

Mediator.

Mediator.

He also worked closely with Eleanor Roosevelt on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

He was a master of the research, also he proved adept at finding small steps of common ground in committee meetings and negotiations. Trygve Lie, the first Secretary General found Bunche was someone who could do the near impossible, and so assigned him to Count Folke Bernadotte, that ill-fated descendent of Napoleon’s wayward marshal, to mediate the Israel partition. The telling of this is a major part of the book, just under one hundred pages, and it proved to be Bunche blooding as an international civil servant, literally and figuratively.

For the ordini, in contrast to the cognoscenti, the Count was murdered in the street, in an open car in Jerusalem wearing a white Red Cross uniform by terrorists who wanted to disrupt all negotiations and drive the fledgling United Nations out. These terrorists — the Stern Gang — included a future prime minister of Israel.

Bunche was catapulted on the spot into the top job as the UN mediator.

There follows a story, familiar today, of intransigence and hostility from Israeli Jews and from Arabs of all stripes. He had remarkable stamina and patience, perhaps born of his own personal experience of enduring the unendurable as a black man, and he kept at it. The key point is simple.

After the murder of Bernadotte all negotiations took place on the island of Rhodes. There the Israel delegation and that of Egypt, the first of the Arab states at the table, stayed in the same hotel, ate in the same dining room, and played on the same ping-pong and billiard tables. There was much posturing, partly, mainly for domestic consumption and then painful deliberations in search of the undiscovered country of common ground. After weeks, there was an agreement for peace, and instead of returning to headquarters to take a bow, Bunche went on negotiate similar agreements with other Arab states, Trans-Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. The first agreement made the second easier to secure, and the second made the third easier and so on.

His approach reminded me a little of MacKenzie King in his days as a mediator. He got the antagonists talking about indirect matters, the size of the table, the menu, all the trivia and as they agreed on these things he went on to other minor points….one after another building up agreement. No agreement was too small because each agreement made the next one easier.

For his labor to end the Arab-Israeli War the Nobel Peace Prize committee recognised him in 1950. He copied much of Bernadotte’s approach, but the substance was his alone. Indeed Bernadotte’s approach was partly his downfall. He was transparent and punctual. He always told everyone what he doing and when he was doing it, and stuck to a rigid timetable. His meetings and travels was published the day before and he was never late for a meeting. Bernadotte also thought the white uniform was protection enough and had no body guards. The murderers had no trouble locating him.

In the lead-up to his murder the extremists in Israel had portrayed Bernadotte as evil incarnate and an anti-semite from the cradle. Think Fox News on Hillary Clinton. The truth is that during World War II as a Swedish Red Cross official Bernadotte had risked his life and limb more than once to extricate people from the Nazis, including many Jews, some later resident in Israel, and also from the Soviets. He survived unlike his colleague and compatriot Raoul Wallenberg.

The burden of racism never ended. On the ocean liner to Oslo to receive the prize he was harangued by a woman at dinner about the inferiority of negroes, she being blind drunk and too vain to wear glasses, did not realise he was a negro, until he told her. But things only got worse.

He was targeted by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. The ostensible cause was that he attended a meeting in 1935 where a self-proclaimed Communist had spoken. The proximate cause was that Alger Hiss had appointed him to the San Francisco delegation to set up the United Nations, and anyone Hiss touched was poisoned in a reverse King Midas.

The accusations were puffed up by the some of the in(per)formers on Roy Cohn’s payroll. Shades of Fox News. The lies were so false that they were hard to refute, but nonetheless Bunche spent two weeks on written replies to fourteen accusations, searching attics, storage trunks, carbon copies, and the like to reconstruct his activities and correspondence fifteen years earlier. The investigation lapsed, but as was the way with these witch hunts, he was never cleared, though nothing incriminating was ever found. The absence of evidence was not evidence of absence.

That he had opposed Communists in the black organisations he had participated in was proof to the conspiracy theorists that he was a secret Red Agent doing so as cover. There is no win available in this cosmology.

Accordingly, accusations against him circulated among the loony right for another generation. No doubt still do in those circles. He was successful; he was black; and he was a United Nations official. These are three things loons hate. These were his crimes. To be born. Guilty. To succeed. Guilty. To serve humanity. Guilty. Why is it that I think of Fox News.

In those days the loons did not own the Republican Party and President Eisenhower demonstrated publicly his confidence in Bunche more than once, while Harold Stassen, the eternal pretender, who had worked with him in San Francisco arranged for him to receive an honorary degree from Penn.

Bunche spoke far and wide about the United Nations, and often emphasised its importance for American negroes as an international conscience. This exposure riled up the rabid right in the States.

Dag Hammarskjōld’s had been appointed Secretary General and after a period of getting acquainted, they worked together as hand and glove, vine and fence. The rule was that no citizen of a member of the Security Council could be Secretary General, ergo Bunche was never a possibility for that job.

The peace he had brokered in the Middle East collapsed a decade later in 1956 when in one of the last spasms of empire, Britain and France invaded Egypt to seize the Suez Canal, while just by coincidence Israel attacked to secure disputed territory around the Gaza Strip, which is still disputed in 2016, sixty years later. Though Bunche tried to intervene, the toothpaste was out of the tube.

In the aftermath of Suez Bunche created the United Nations peacekeeping force. There had been UN observers before but these peace keepers were supposed to keep the antagonists apart, not just report on what happened. The practice of painting vehicles white set by Bernadotte was continued. While no international uniforms were created the blue hats were used to identify the UN troops, first war surplus USA helmet liners painted sky blue, the berets came later. That was the first demand for the supply of peace keeping troops that created the market which exists today, wherein cash strapped Third World countries sell their soldiers to the UN.

More than 3,000 UN peacekeepers from 120 countries have been killed on duty as of 2016.

More than 3,000 UN peacekeepers from 120 countries have been killed on duty as of 2016.

His home life was sacrificed to his travels and to the enormous pressures on him. Though when in New York he had something akin to a normal life for weeks at a time. He and Ruth bought a house in Queens where she lived until her death in 1988. Bunche, by the way, was a heavy smoker but drank alcohol only socially and not always then, apart from the toasts.

Then came the Congo and that just about destroyed the United Nations. When Hammarskjöld was killed, Bunche was once again catapulted into the top job on the spot. Once again in this telling, Belgium earnt the reputation as the worst of the colonisers. The Congo was the biggest in a relentless flow of crises: Yemen, Kashmir, Cyprus, Somali, Namibia, Bahrain, Biafra, Vietnam, and always the Middle East, just to cite the headlines. In addition there is a crisis a day within the United Nations itself as the Soviets undermined it, the non-aligned movement discredited it, and the United States suspected it. Back and forth goes Ralph Bunche.

There is more to his story but perhaps this is enough to whet any appetites out there.

Bunche turned the other cheek many times and he forgave but he did not forget.

Ergo when President Harry Truman offered him the number two job in the State Department, he declined because in Washington D.C. years before when his daughters’ pet dog died it could not be buried in the pet cemetery because the pet cemetery was whites only. Think about that.

When UCLA offered him an honorary doctorate to bask in the glow of his Nobel Prize, he declined it because though he was objectively (by GPA) the best student another had been made class valedictorian. To his credit this other tried to refuse the honour because he knew Bunche had the better GPA.

While on the subject of declines, he also declined Adlai Stevenson in 1951 and Jack Kennedy in 1959 who both asked him to be a foreign affairs advisor at twice the UN salary in their presidential runs. He preferred the UN and New York City. Had he accepted Kennedy, he would likely have become Secretary of State.

When time and tide permitted, he was active in the Civil Rights campaigns.

Protestor with Dr King.

Protestor with Dr King.

Another nail in coffin prepared by Hoover J. Edgar.

Brian Urquhart was a long-time British diplomat at the United Nations.

Much of the book is a record of events in which Bunche participated from which the readers learns little about the man himself. How he could summon the energy and good will to attend one crisis after another remains a mystery, because it became painfully apparent after the Congo that the United Nations could do little. Still little is better than nothing.

Reading about Bunche’s experience as a negro reminded me that once leaving the Hasting Public Library one cold day, in say 1962, I walked out the door and along the sidewalk with a library patron I had often seen there. I was in high school and he was a mature man, with a frosted lens in his eye glasses that implied the loss of an eye. He was old enough to have been in World War II. He was always clean and tidy.

We had seen each other often in the library but never spoken.

That day he did talk to me briefly. While I do recall, and I just tried to retrieve the data from memory Alpha, what precipitated his comments, but I do remember his comments, which were to the effect that every negro in Hastings received communist propaganda. It was said in such a way as to imply that they were receiving it because they were communist themselves. It left me speechless and he walked on as I turned off. That would be all six of them.

Recalling that incident now reminds me that in a way, some of what I became traces back to one of the blacks. In junior English class in high school, one of the students was Sam Mullins, who was slow on the uptake but genial, and once as we walked out of class, he asked me about my plans for going to college. I was surprised, too immature myself to have thought that far ahead at the time, and I said I probably would not go, and he scoffed and said I should. He and I were not buddies but it was one of the first times I was prompted to think about the future like that. Other prompts came later, some institutional, and some personal, but that was the first.

(The teacher was a very short woman who always told us the answer before asking the question, so anyone listening, albeit a minority, could answer. We read Stephen Crane’s ‘Red Badge of Courage’ in that class. That has stayed with me. That seemed then to be a book she placed special emphasis on.)

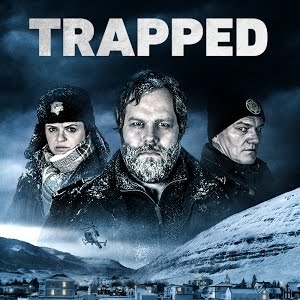

‘Trapped’ (2015)

A ten-part television series from Iceland. Nordic noir without the computer graphic images of gratuitous gruesome gore that typify far too much of the genre. IMDB rates it at 8.2.

It kept us coming back for more. Each fifty-minute episode ending on some crisis, and each subsequent episode beginning with a recapitulation. Slow and old fashioned.

What’s to like?

The pace is measured and low key. No shouting, table banging, or the other crutches mentally impoverished screen writers and directors use to distract from the superficiality of the work.

The setting is great travelogue. Snow, mountains, and fjords, oh, and plenty of ice on the north coast of Iceland.

The Iceland’s weather is a major character that directs and limits what the human agents can do.

The interaction of the public and private lives of the characters in the small town which is cut-off by a storm.

The three small town cops, each different, make a good team, fallible though each is.

The crippled watcher. But we got too little of him.

The several wheels within wheels which were neatly wrapped up in the end.

The redemption of the falsely accused and imprisoned boyfriend.

‘The devil entered me’ said the grieving grandfather.

That most of the trouble was all homegrown and did not come on the ferry.

The mixture of languages, Icelandic, Danish, German, French, and English.

The cannibalistic media. Another tired trope but I am not yet tired of it.

What’s not to like?

The big city cops are a trope, arrogant, easily satisfied, and incompetent.

The ex-wife’s boyfriend is ever present, leading to the conclusion that he will figure in the plot, but he does not. A blue herring.

The ferry captain’s change of heart was pat.

The police commissioner in Reykjavik was built up to be important in the story and then dropped.

Andri’s backstory was a boring distraction as they always are. This is another crutch.

We found it on SBS On-Demand. Hooray!

But we found it very difficult to find on the telly. The TV screen search function could not find itself! Nor could it find ‘Trapped.’

The iPad app is great. It was easy to find ‘Trapped’ on it but we wanted to watch it on the big screen in front of the easy chairs. The app does not communicate with the television as far as we could see.

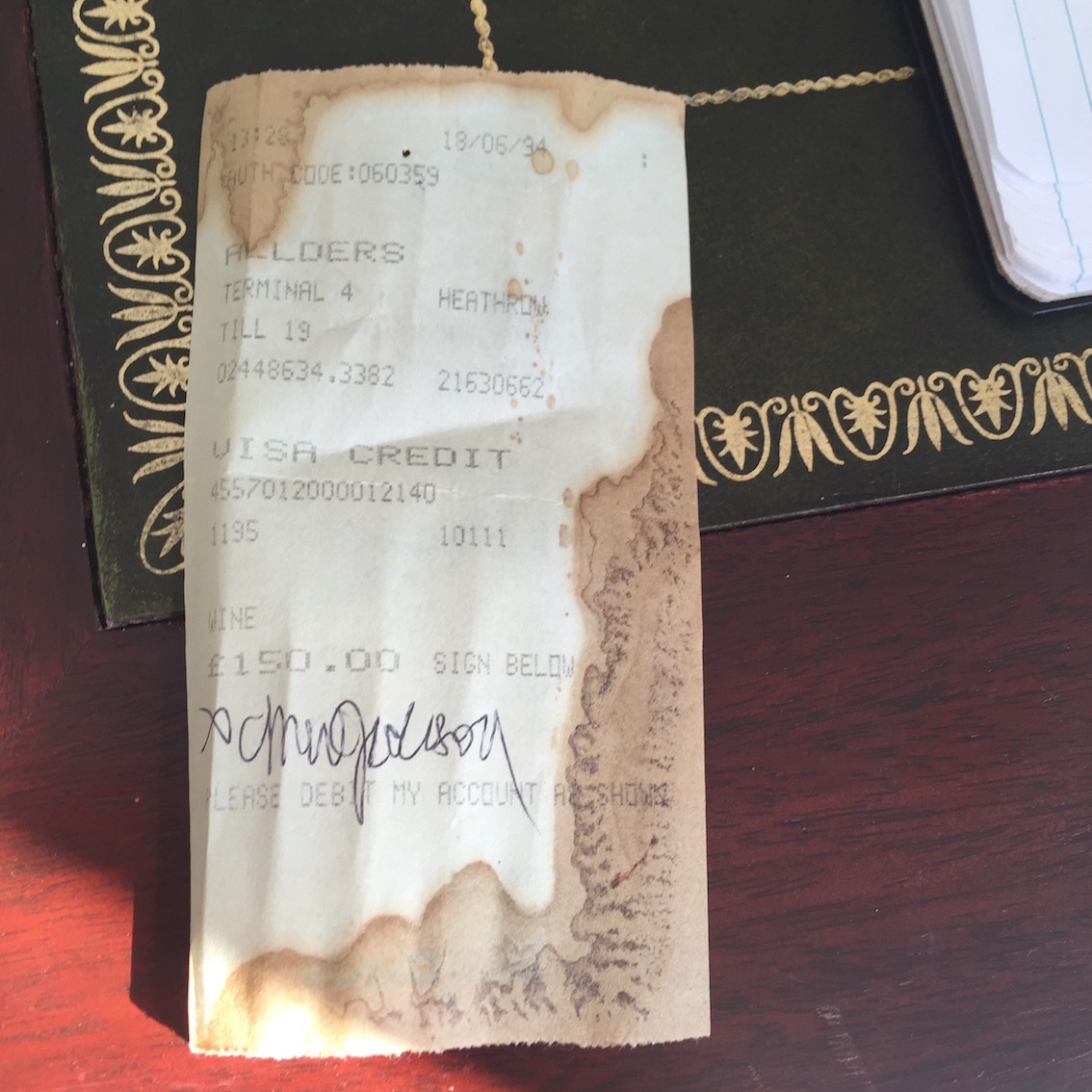

Heathrow- never again.

Heathrow is the worst airport I have had to go through and I have a taken a vow to myself never to do so again. To go to Dublin a couple of years ago we went through Amsterdam instead. I said that recently and was challenged with a barrage of stories about other airports.

Gosh, we travellers are picky.

I stopped to think about my experiences at Heathrow, good and bad. Good is a shorter and less intensely-felt list so I will do it first. I include everything from cab drivers to the elevators because it is all part of the Heathrow experience, n’est pas?

The good.

I had a few painless check-ins that I can no longer remember. The more so since some of my passages were on business class tickets.

When it came at long last, the train to Paddington was wonderful. It reduced the pain from the distant airport a lot and it offered the first British train station I had ever seen that was not filthy.

Once when I was particularly discombobulated, turning left instead of right, I lined up in the wrong place at United, and was treated like a king. I expected to be sent back around the corner to the right place but instead I was checked in with a happy smile. The line I hit by mistake was one reserved for VIPs, a category that has never included me.

In 2004 we rented an Avis car for drive around and that was smooth, and while finding the car in a distant lot we watched a Concorde take-off: loud and burning a lot of oil. The Avis agent gave a few personal tips on petrol that we used.

Here is the best, once very early one morning in 1994 while waiting for a flight I saw a sign at 8 a.m. offering free tastings of Chateau d’Yquem at a bottle shop in the terminal. Yquem is worth lining up for any where and any time. So I lined up outside the door to wait for 8 a.m. to arrive, and it did, and I did taste five vintages of this nectar of the gods. I knew that Baron Rothschild used to drink half a glass at breakfast over ice instead of orange juice; I knew that locals genuflected as they passed the vineyard. Now I knew why. It was part of a sale of the stock from a very high-end restaurant that had gone into bankruptcy and the stock had to be sold by the end of the month.

I bought a bottle for about a £150 and carefully carried it back to Sydney. That was a lot of Australian dollars worth of pounds.

A dinner party was arranged and at the end of the banquet, the Yquem was produced and knocked us speechless. I genuflected. We still keep the now empty bottle in a place of honour. Well, in the garage but I found it and the original docket — stored within — as above.

I learned a trick to cook an egg over bread in a microwave once when we ate at a cafe in a terminal. We still refer to that as a Heathrow egg.

The Bad

Ironic.

Ironic.

Taking the Tube to Russell Square, while a struggle, was convenient and I did that many times because of the British Library. Happily the lifts and escalators worked there. Once out of the station I had to walk with the bags to the hotel, or if the bags were too much, then haggle with a taxi driver for a short ride around the Square, and that seemed to get more difficult each time I tried it. Sometimes a double fare was not enough to get the bags and me around the square to the hotel.

The worst single event was one morning waiting in line outside at an airport hotel for hours for the airport bus to arrive. I had gone to that hotel the night before for an early morning flight. There came no bus and no information as more and more travellers emerged from the hotel to join the queue. The line of patient waiters grew longer and less patient. No mobile phones then. That was the day the parking garage fell down. There was never any information but cab drivers bringing people from the airport spread the word and packed us up for the terminals. My Air France flight was delayed, cancelled, etc. Instead of arriving in Florence at 10 am to find my hotel in broad daylight, I arrived at 10 pm and it took some time since I was driving a rental car in the dark in an unfamiliar environment per Italian rules of the road.

In a logic that neither Mr Spock nor I understand, the left luggage office at a Heathrow terminal was on an upper floor. Cheaper floor space, I suppose. Leaving and later collecting luggage meant getting it to that floor. On one trip the lift to that office was out of order both when I left the luggage and later when I went to collect it, so it had to be man(me)handled up and later down the stairs. No explanation, no apology, no discount on the fee for the extra trouble. Just the usual snarl when I mentioned this fact to the attendant who had no doubt heard it all before, and it bounced off.

The most typical experience: to exit the aircraft and to walk through one corridor after another pulling the reluctant carry-on bag over layers of wrinkled and sagging carpet that velcros the wheels. I timed such a walk once and remember it to be 25 minutes through dim and dank corridors.

Then came, as always, the wait in line for the immigration stamp. Yes, I have timed that, too, and hit 45 minutes once. When at last I got to the officer, he was polite, pleasant, brisk, and efficient and the whole transaction lasted less than 30 seconds.

On a bad day.

On a bad day.

When departing once, I disembarked from the bus between terminals at the door to find a queue out of the building. There was no attempt to manage or organise the line. It was raining, as always. and I was not dressed for it since I had assumed I would not be out in the weather. Was this the line to be in? I did not know but I could not otherwise get into the building so I waited, and in the end by some miracle it was the BA check-in, and once I got to the front it was quick, pleasant, and done. But it was an anxious wait, for if I was in the wrong line, by the time I realised it, it would be too later to find the right line for the trans-oceanic flight.

On a good day.

On a good day.

My briefcase split and spilled in the rain once going to a rental car. Well, it was a bad experience and it happened at Heathrow, so it is included. (It was the Japanese one that never seemed to hold anything, though it was heavy and large, there never seemed to be any room inside; it came full of lining, padding, inside pockets all of which precluded putting anything else in it.)

We stayed once in an airport Thistle Hotel at Heathrow. It may be the worst hotel I ever experienced. Faulty Towers would have been an improvement. Nothing brisk, efficient, or pleasant about it. There was no line but check-in seemed like a canto from Dante’s ‘Inferno.’ Getting the bags to the room, over lumps in the floor, sagging carpets, fire doors off the hinges… Communicating with the staff, well, it proved impossible. I say ‘may’ be the worst because we once stayed in a Thistle in London…

One taxi driver, having studied a year and a half for the license, took me to the wrong airport hotel. It was late and I was exhausted from a long flight, and in any event I did not know where the hotel was. There was no definitional argument here. The driver, when we pulled into the drive way, admitted this was the wrong hotel, not the one I had ever so slowly and clearly stated and he promptly turned off the meter and turned around and took me miles to the right hotel on the other side of the airport.

Once I opted for the Heathrow bus from Russell Square at 5 a.m. The pick up in the damp winter darkness at 5 a.m. was on time and that was the last time. Traffic gridlock started at the next intersection and it took hours to get there. I had allowed four hours and just barely made it.

This was the occasion, standing under the Heathrow bus sign waiting patiently, when a taxi driver pulled up and told me the bus was slow, uncomfortable, and he would gladly drive me to Heathrow and even reduce the fare. I said no thanks. He persisted, and I mean persisted. He mentioned prices and I kept saying ‘No, thank you.’ [Keep reading, the punch line is coming.] Finally, he had got himself worked up and said ‘Well what would you pay?’ and I said ‘Five pounds [which was the bus fare]’ and he exploded. Five pounds! I was a crook, a crazy man, and typical foreigner robbing the working man…. and off he went shaking his fist at me. What a home life he must have.

The bus was an improvement, apart from the time, over the Tube. Taking luggage on the Tube to and from Heathrow was… a great convenience and a major hassle. The more so in peak hour and when, pray tell, is not peak hour not the Tube.

Any reader who gets this far is invited to compose a line or two of their own experiences.

‘The Ivory Grin’ (1952) by Ross Macdonald

A gritty tale of unrequited love(s), madness, and sacrifice from the stylist of noir krimis. Raymond Chandler had a ear for dialogue, while Ross Macdonald has a jeweller’s eye for descriptive metaphors and images. Lewis Archer is his avatar.

While the novels obey all the conventions of the genre in its time and place, it also turns them inside out. The PI’s boredom counting flies on his office windrow is interrupted by a femine fatale, as required, but this one, despite the diamonds and furs is barely a femme at all. A very mannish woman is she. Archer’s emphasis on her lack of feminine qualities is partly the everyday sexism of the era but it also turns out to be a pivot in the plot.

As always with Macdonald, everything from the color of the sunset to the hats impart texture, reveal character, and unwind the plot. Nothing is ever wasted in his novels.

This is a triangle of three families, locked together by one of the offspring. Bess is literal when she says she loved him to death. Lucy, the loyal nurse, sees more than she ought and cannot get out of the vortex. That manly woman is normal compared to her brother, who has a gun. Assorted other lowlifes pass by, but the worst of the lot is the quiet suburban doctor.

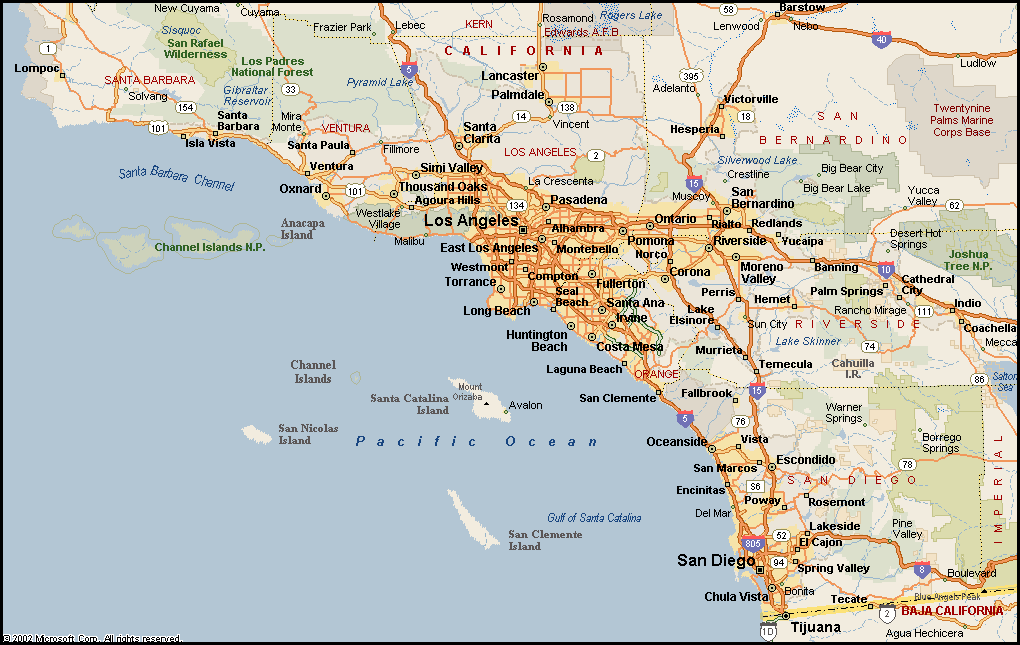

Archer country

Archer country

There are some innocent bystanders along the way, Alex the love-sick boy who pines for nurse Lucy and the love-sick girl Sylvia, who pines for playboy Carl, and who becomes in a convolution of the plot Archer’s client.

I still have the paperback copy of this I read In the 1970s but I re-read it on the Kindle. I turned to it to find something to read after a series of misfires with annoying, self-indulgent, padded, and pointless krimis. If only Jane Austen knew what she had spawned when she told would-be writers to to write about what they know. Far too many only know the IKEA catalogue. Why continue the search for quality when I know right where it is.

Sometimes Macdonald’s metaphors and images come so thick and fast that they create a traffic jam in the reader. Sometimes the psychologizing gets in the way of the momentum of the story. But these are the prices of admission.

Archer is named for Sam Spade’s deceased partner, Miles Archer, who believed in fifty dollar bills.

Macdonald’s krimis are hard boiled in that they are unsparing In word and deed. The villains are villainous with little of no veneer. Often the mystery is less who dun it than why dun it. That is the psychological depth that distinguish his works.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

This one is the fourth of eighteen Archer novels over a thirty year period.

At least one of his krimis had a rave review on the front page of the ‘New York Times.’ The book was ‘The Underground Man’ in 1971 and the reviewer was that southern novelist of note Eudora Welty.

Yet none of his novels was ever awarded a paramount krimi prize like the Edgar. Figure that out, Mortimer.

Had I to pick one, it would be ‘The Blue Hammer’ in 1976, his last completed novel. I recall still how eager I was to get it and to read it, taking it with me when I went jogging to read a few pages while catching my breadth.

A mature work. in it he is not trying so hard to crowd in metaphors and there is less speculative psychologizing by Archer, while retaining the descriptive richness, the psychological depth, the ambiguity of motivations, and the equilibrium of the moral balance. In his books, unlike life, the world bends towards justice of a kind.

Perhaps Macdonald wrote one book eighteen times, as has been said, the same story of twisted love, divided loyalties, wayward offspring, mental imbalance, irresponsible parents, each magnified by a the glare of money in the prism of California sunshine that blinded the individuals to their own deeds.

By volume eighteen the biggest mystery is Lewis Archer himself about whom the reader learns almost nothing. He is a lens that reveals the story of those around him. By his actions we can see he is an inveterate loner, but one who warms readily to some women he meets for their physical and intellectual charms and vulnerability; he is dogged, and hard working. He wears a hat which he sometimes takes off. In one story we note he drives a light blue car, in contrast to his dark blue mood. At least he has a name, unlike Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op.

There is less about Archer in the eighteen titles than there is about Philip Marlowe in one of Chandler’s books. Archer has no backstory. The reader is not manipulated into feeling sorry for him. Why should I, he certainly does not feel sorry for himself.

Archer reports on the dirt under the carpet of the American Dream in the golden sunshine of Southern California, and it is very dirty. Yet he meets honest people whom he likes, and some he even admires. Say in contrast to the BBC’s Christopher Foyle whose world is populated entirely by liars, cheats, and murderers, often dressed in gold braid with aristocratic titles and important government jobs, Foyle’s is a world without hope, but Archer’s world has hope, and that is what keeps him going.

‘The Adventures of Tom Stranger, Inter-dimensional Insurance Agent’ (2016) by Larry Correia.

The title alone was irresistible, and my resistance is futile, quite often.

It opens with the destruction of Earth and then it gets worse!

Fortunately, Earth had an All-Catastrophe policy, no exemptions and no deductible, with Stranger and Stranger Insurance, and Tom Stranger appeared in time to put things right, dragging in his wake one very reluctant intern. (President John Wayne took out the policy and arranged for eternal payment of the premiums.)

Tom offers the best customer service in the universe, and he means that literally. Anything less than a ten our of ten is failure, and Tom does not fail, not even when confronted with dinosaurs sporting Nazi insignia. (Part of a Trump delegation.)

The intern thought a six-month stint in insurance would be, like you know, easy. As a Gender Studies major he had not actually bothered to read any of the print, fine or actually otherwise, but, like, was waiting for the movie, actually, like, so he had no idea, like, actually what he had signed on for actually. Well ‘no idea’ might be a generalisation. ’Thought’ is not the right word. No thinking occurred. The intern is a thought-free zone.

Moreover, this Gender Studies intern was from…yes, it gets worse, Chico State, where beer stains on tee-shirts are, well, like, cool, way cool actually.

Tom would like to return his intern from whence he came, but duty calls and redeeming a Gender Studies major from Chico State, now that would be a challenge of inter-dimensional magnitude.

But first, Tom and the intern find themselves in Nebraska where they must battle the ultimate evil. Gulp!

Tom is rated at 104.3 Bear Grylls while the intern is a puny, 0.4 BG. The Bear Grylls rating refers to what it would take to kill BG. It is an inter-dimensional standard. [Love it!] Tom can man-up, or rather Bear-up, to the ultimate evil there among the corn fields, but he will have to shelter that puny intern who is less than half a Bear Grylls.

Larry Correia

Larry Correia

NO SPOILER.

It is two hours of spoof, like a long skit from SNL in its heyday, read by Adam Baldwin who manages all the inter-dimensional voices, including Muffie back head office. Discerning readers may remember Adam Baldwin as Animal in ‘Full Metal Jacket.’ It is high octane all the way.

The corporate speak, the obsession with the customer experience ratings while ignoring customers, the constitutional inability of an insurance company to pay a claim, the CVs of the policy-holding political leaders encountered along the way, the numb brain of the intern, all of it rings true. How can this be fiction in a world where Donald Trump is reality? Go figure that out.

It has been a while since I used Audible so I had another look and found this corker. I listened to it while pumping iron and pushing pedals at the gym. I call it a krimi because there are plenty of crimes, but in a boring old book store it would be sci-fi.

‘Four for the Boy’ (2005) by Mary Reed and Eric Mayer

The fourth in a series set in Sixth Century in the Constantinople of Justine and Justinian, emperors of Nova Roma. Our principal is John, whose mercenary background has brought him to Constantinople … a slave. He bristles at his status but makes the best of it.

Amid much palace intrigue John, as the Emperor Justin is passing the rule, reluctantly, to his nephew Justinian, is assigned to an excubitor. Felix, he from the Teutonic woods, to investigate the blatant murder of a rich citizen in a church. The Emperor Justine designates them, perhaps more to slow, than speed the investigation for John is after all a slave, and no citizen is required to speak to him. Felix has only a middle rank, poor Latin, and is not the sharpest knife in the drawer. The city’s Prefect resents their intrusion and fobs them off with other duties.

Justinian.

Justinian.

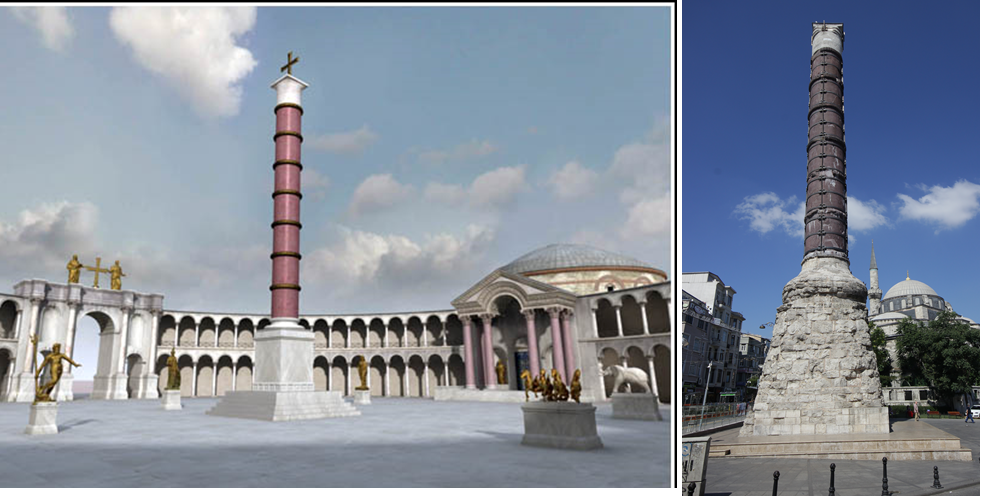

On their fools’ errand, they go here and there in Constantinople from the Hippodrome to the Golden Horn, to the Bosphorus, to Constantine’s column, to the Great Palace. Each time I shout out, ‘I’ve been there!’

Constantine’s column as it was and and it is today.

Constantine’s column as it was and and it is today.

Two such low level functionaries have little access to the great and good, and the few they meet are quick to tell them that. But they do have more access to the panoply of slaves and servants of the great and good, from door men, to kitchen hands, to fishermen who supply the food, to prostitutes. While many of these humble folk are too careful not to say much, sometimes what they do not say, is itself noteworthy. That is the conceit of the work.

I have read two other entries in this series. Each is packed with period detail which is salted throughout the work. There are no long expositions, just everyday asides and comments. Felix is an excubitor and we learn as we go that means he is a palace guard. We are spared an exposition of the nature, organisation, and origin of excubitors that would be inserted by some other writers to discharge their learning. Here the hand is light and the exposition is slight; the emphasis is always on the matters at hand.

However, John’s backstory lingers more than it should for this reader. We would be better off to find out what kind of man he is through his actions, pace John Stuart Mill, than be prompted by his unfortunate biography. My empathy for such contrivances is zero these days.

The title makes sense in the end, though the villain springs from no-where. But it does tie up all the loose ends.

Eric Mayer

Eric Mayer

Mary Reed

Mary Reed

While this is a foreign and, in many ways, a repellant world, the authors do not attempt to explain or justify it, they just present it in its own terms. There are the fantastically rich and the poor who live on the streets, just as in Reagan’s America, and in Obama’s too. Indeed we have such dwellers in Sydney these days. All in all, the authors bring to life a cast of characters from mute beggars, clever scientists, vain artists, working stiffs, court intriguers, wealthy fops, as well as Emperor Justine and soon-to-be Emperor Justinian and she who will be obeyed, Theodora.

Many unusual terms like excutor are used and there is a eight-page glossary at the end for those who must know before turning the page.

‘The Shadow Walker’ (2006) by Michael Walters.

An exotic krimi set in Mongolia as it emerged from the Red World in the 1990s.

Where is Mongolia? Having seen so many episodes of Eggheads with contestants who do know where their elbows are, this map is included.

A series of murders, each more terrible than the previous one, in Ulaan Bataar galvanises attention at the highest level, the more so when a British technician is one of the victims in a five star tourist hotel, and then a senior police officer.

Genghis Khan, a landmark mentioned several times in the novel.

Genghis Khan, a landmark mentioned several times in the novel.

The minister of justice dispatches the one man he can trust to co-ordinate the police efforts, Nergui, he of one name. Into this brew steps a British police officer, Drew MacLeish, sent, as a sop to the slain technician’s family back home, to contribute to the investigation.

Ulaan Baatar

Ulaan Baatar

It is a nice context and premise. There is some travelogue in and around Ulaan Bataar, and the Gobi desert. The centrifugal and centripetal forces of the ancient traditions and new opportunities for wealth are portrayed. All of this was interesting reading.

Ulaan Baatar

Ulaan Baatar

The exposition is far too wordy for this reader. Too many long speeches about either the perils of modernity in Mongolia or the backstories of the principals, which always bores me to tears. In this case Nergui’s backstory is laid on with a trowel; he a man among men, a gentleman and a scholar, a preternatural athlete…. Oh hum. Sainthood can only be a matter of time.

The Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert

Let’s get to the plot and as it unwinds we better learn of the characters. I almost wished for Mike Hammer, so appropriately named. You always know where you stand with Mike, under his heel. He spent no time talking about anything but the beating he was giving you.

The author cleverly turns the language barrier into an opportunity. When Nergui speaks to natives in Mongolian, Drew studies the expressions and body language and makes inferences from those observations. The conceit is that body language and face expressions cross the cultural barrier. Perhaps they do not. Likewise, Nergui uses the presence of the British chief inspector Drew as a lever to secure cooperation from officialdom, both Mongolian (in the ministry) and British (in the embassy).

Michael Walters

Michael Walters

Much of the tension springs from some tired clichés about politics and politicians. The unscrupulous behaviour attributed to politicians in general in these pages can be found in any middle to large organization. There is, surprise, nothing unique about politics, except its ready exposure to such clichés. I did not find any explanation of the title.

The denouement is deus ex machina. [Look it up, Mortimer!]

Intensity, Democracy, … and Brexit.

Democracy has always been about counting the votes and all the votes are equal. That is a given. So given that few stop to think about what it means. It means the minority, the losers may lose a lot unless the scope of voting is limited.

Though all votes are equal, not all outcomes are permitted. Huh? Human rights are sacrosanct, that is, they cannot be voted away by a majority. Certain other liberties and many institutions are put beyond voting, like a high or supreme court. Although many students have told me that such reservations were elitist and anti-democratic. Surely a vote for the Australian High Court would put Derryn Hinch on the bench.

Whoa! Too fast? Better stop for an illustration. X may vote ‘Yes’ and Y may vote ‘No,’ but the result matters far more to Y, if the vote is about Y’s life, limb, family, or property, than it does to X. Yet their two votes count the same. This is the problem, no account is taken of the intensity each has.

Interest is often, usually, entwined as vine to fence with intensity. I may not much care where the new distant freeway goes but those near it do care, a lot. Yet my vote equals, and cancels, one of theirs. Interest is this case refers to the immediate and material.

Intensity may also be ideological as well. Within ideology we shall include for purposes of this discussion religion, though to some adherents it is as material as snowfall. What consenting adults do in the privacy of a home is of no interest to me, but some ideologues may feel soiled by knowing of the possibility of some such activities. Indeed they may be so intense about such activities that privacy is a lesser value to be breached in the interest of policing such activities. Think bathrooms. Be that as it may.

In a polity where voting is free, that is, voting is not compulsory, turnout is one indicator of intensity. Those that care about the result are more inclined to go and to vote, even if that requires advanced registration, and on the day the weather is foul, the wait in line is long, the polling place is distant, the officials are hostile.

Intense voters go to vote, rain or shine.

More than that, intense voters round up like-minded others and take them along to vote as well, and most will then vote as the opinion leader does.

That the wind and rain in Britain may have reduced the turnout in the Brexit vote is another reminder of intensity. The Leave voters voted.

I wrote my first seminar paper in graduate school on ‘Intensity in Democratic Theory.’ It opened with the following epigram:

‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.’

From ‘The Second Coming’ (1919) W. B. Yeats

William Yeats

William Yeats

My last undergraduate class had been English poetry, famed of 8 a.m. on Saturday mornings in McCormick Hall with Dr Harwick. These lines seemed a fitting perspective on democratic theory, but it irritated the political science professor who read it. He was likewise irritated when in the next paper I opened with Robert Frost and ‘Mending Wall’ to start a discussion of political institutions.

Robert Frost

Robert Frost

I also quoted Saint-X, further betraying my literary side.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

‘Let a man but burn with enough intensity and he will set fire to the world,’ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in ‘Terre des Hommes’ (Wind, Sand, and Stars) (1939). The burning man, by the way, was Adolf Hitler. Saint-X died in 1944 while flying for the Free French in North Africa.

For further reading, the sources I can recall from that intensity exercise are these.

Robert Dahl, ‘A Preface to Democratic Theory’ (Chicago University Press 1956).

Willmore Kendall and George W. Carey, The “Intensity” Problem and Democratic Theory, ‘American Political Science Review,’ Vol. 62, No. 1 (Mar., 1968), pp. 5-24.

Giovanni Sartori, ‘Democratic Theory’ (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962).

Today I did have a look at the Web of Knowledge and found a few more recent sources, but none that claimed or seemed to be definitive, all of which cited these three as foundation texts on the subject.