What do socialism and the Republican Party have in common? Read on.

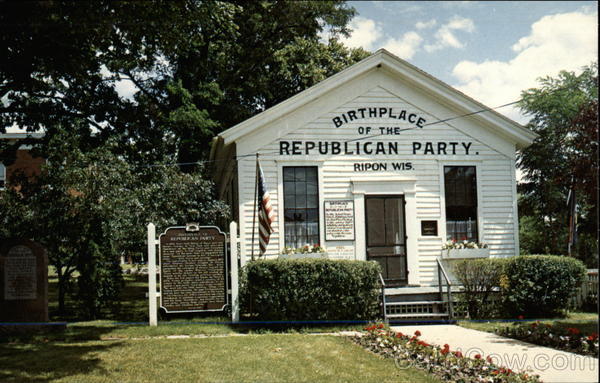

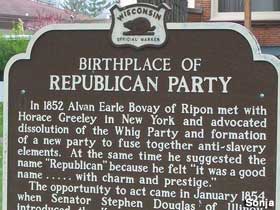

In ‘Murdoch’s Organ’ (aka ‘The Australian’ newspaper) of 5 April one KImberly Strassel mentioned Ripon Wisconsin as the birthplace of the Republican Party in the context of the forthcoming Republican primary election there pitting Donald Trump against all comers.

The little white school house in Ripon Wisconsin is the symbolic birthplace of the Republican Party because in about 1852 the Free Soil Party was first organised there, and it morphed into the Republican Party in 1860 when Abraham Lincoln was its nominee for president, and the eventual winner.

The Whig Party was slowing imploding in parallel with the rise of the Republicans. The Whigs had elected presidents, but had not succeeded in electing its foremost figure and greatest statesman, Henry Clay, whose frequently quoted remark ‘I’d rather be right than president’ proved all too prescient. Clay was the great compromiser whose compromises for a generation staved off civil war and with his death one of the legs of the table of compromise was lost and the war followed.

These days to call someone a compromiser is a dire insult. One must be consistent and uncompromising to win the adulation of the addled minds of the media.

The Whigs had never supposed slavery was a major issue and the Democratic Party, that genetic issue of Thomas Jefferson, himself a slave holder and more importantly a worshipper of states’ rights above all else, had scrupulously avoided the subject. The one church Jefferson honoured was the state house. Andrew Jackson that other founder of the Democractic Party did not mince words about states rights, he simply declared the slaves inhuman.

The Free Soil movement opposed the extension of slavery in the new western states, starting in the north west with Wisconsin because it feared slave labor would undermine…free labor. The short lived Free Soil Party was born in the little White School house and there is more.

Three of the five signatures on the minutes of the first meeting in the Little White School House came from individuals who had been socialists!

Gasp! Shock! Horror!

Yes, an Associationist Fourier community inspired by French utopian socialist Charles Fourier had flourished in what is now Fond du Lac county at Ceresco just east of Ripon for a few years and as it was winding down some of its members aligned themselves with the rising tide of Free Soil. Associationism was a version of Fourier’s phalanx scripted for American ears by Albert Brisbane and promoted, by among others, Horace Greeley. It was Karl Marx who labeled Fourier a utopian socialist, well Frederick Engels, in fact, but few acolytes notice the distinction.

Ergo the seed of the Republican Party bears the original sin of S O C I A L I S M. Not a fact to be found on the Republican National Committee’s website. Not even a fact to be found in Ripon where it is reported that the early records were destroyed in a fire. But a fact that can be confirmed in the Library of Congress where other records survive.

I wondered how anyone knows of the Party’s history since the Republican National Committee has been stripping history from its web site to comply with the worldview of its Tea Party rump these last few years. To be sure the Ripon Society still exists but it is a shadow of its former self. The list of Ripon Republicans (= by definition liberal, some avant le mot) is impressive for their achievements and noteworthy for their near eradication from the GOP’s official history: Herbert Hoover, George Norris, Thomas Dewey, Arthur Vandenberg, John Lindsay, Wendell Wilkie, Earl Warren, Margaret Chase Smith, Henry Cabot Lodge, Nelson Rockefeller, Jacob Javits, Olympia Snowe, Arlen Spector, Nancy Johnson, Christine Whitman, and Harold Stassen. Few, if any, of these giants would be acceptable to a party that nominates Donald Trump for high office. These days the Ripon Society celebrates the likes of Dennis Hastert, mudslinger extraordinaire and one-time wrestling coach.

A liberal Republican (1) was an internationalist who worked with international organisations like the United Nations and preferred multilateral action to unilateral, (2) who worked with trade unions to strength the society, and (3) and advanced civil rights for all. See how many Republicans would say that today.

By the way GOP stands for Grand Old Party, which was a moniker the Republicans embraced as a nickname after the American Civil War in parallel with Union Army veterans who styled themselves the Grand Army of the Republic or GAR in post war celebrations and reunions. The segue was from GAR to GOP.

Author: Michael W Jackson

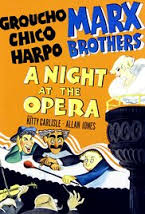

‘A Night at the Opera’ (1935)

It was a morning on the Sydney Opera House Quay at the Dendy Cinema Theatre where Jim Kitay and I went to see the antics of the Marx Brothers, Julius, Leonard, and Arthur, and so on. Neither Karl, Milton, nor Herbert are in this one.

It is feature length at 93 minutes, cut from the original release of 98 minutes, and it is a big production, i.e., a large cast, and some set-pieces worthy of Busby Berkeley. Old troupers like Margaret Dumont and Sig Ruman liven things up. The screen play is by that stalwart of the typewriter, George Kaufman. It is scored at 8.1 on the IMDB. That is impressive.

Among the outstanding scenes are the crowded stateroom on the steamship and the aerial acrobatics in the theatre. There is also a good deal of ‘Il Trovatore’ sung by Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones. Ms Carlisle continued to sing well into her 90s, says the fount Wikipedia.

Otis B. Driftwood, now there is name with which to conjure, reminds me of some scholars I have known. Always on the prowl for easy takings and completely irresponsible.

These things are best seen on the wide screen without distractions, but if that is not an option, turn the lights down and cue it up on the idiot box. These idiots always have something to offer.

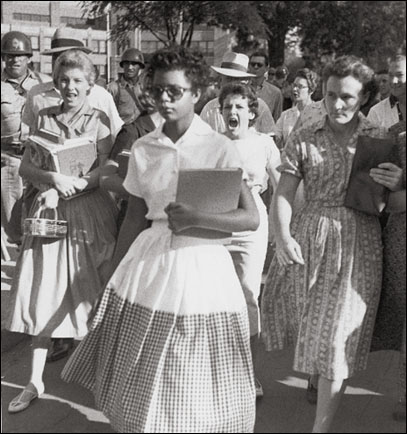

It’s all about race.

There is only one domestic issue in the United States: race.

That President Black Obama got elected was a shock. It certainly surprised me. And a great many people have never accepted that result.

Here are the haters at work. Bibles clutched, voices raised, faces red, necks distended. What the haters feared has happened. These are the Trump and Cruz voters.

Here are the haters at work. Bibles clutched, voices raised, faces red, necks distended. What the haters feared has happened. These are the Trump and Cruz voters.

Of course, the sophisticates have learned to code their reactions for the media, but the heart of the matter is that a black man is president!

How can that be? Those unreliable voters, again!

In the years since his election many means have been tried to rein in voters to prevent the recurrence of such an aberration. They take many forms but commonly raise the barrier to voting while easing the capacity of voter-buyers to do so.

The more direct methods of insuring the outcome as practiced by these Trump voters.

The more direct methods of insuring the outcome as practiced by these Trump voters.

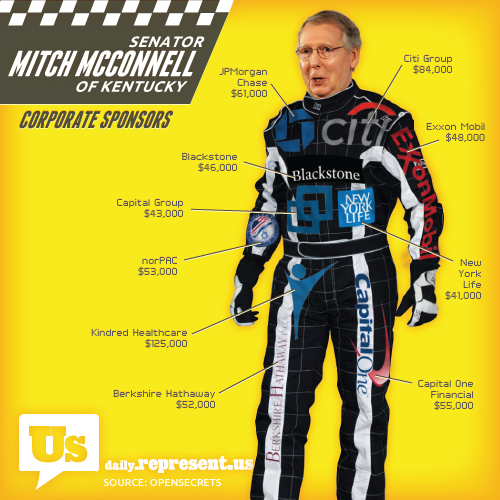

Racing car drivers wear suits labeled with the logos of their sponsors. So should politicians, as has been said by others. Every Representative and Senator should appear thus besuited. Ditto candidates.

The haters prefer someone like Senator Mitch McConnell.

The haters prefer someone like Senator Mitch McConnell.

President Clinton once said something like that title about race, and he was right. Responses to a host of specific issues comes down to race. Unemployment, mortgages, education, health care, even veterans’ care…. The list goes on.

Mr Spock, the logic, is academic, not administrator.

Administrator logic? The moral of the story is that we lie in the bed we made.

When yet another convoluted directive did the rounds of the University, one Ph.D. with enough time on hand to comment wrote, acidly, ‘Administrator logic’ and very kindly hit ‘Reply All’ so that we all could savour the wit and insight.

It is the sort of snide remark that can only be made by the naive. ‘Why so,’ asks Mr Spock?

The rules and regulations of the University inevitably trace back to a committee of professors, lecturers, and other academics. That we make our own rules is the ultimate explanation for the way they are.

With a committee of smart people, there is usually a competition to show just how smart each person is by thinking of things to include, cases to anticipate, including layers and layers of protection for students, especially those who manipulate the system the most.

I observed, and at times as a committee chair had to deal with, this competition to complicate, and the zealous desire to defend poor defenceless students against the mean University (embodied in yet another committee of academics).

To take one pivotal example, the unit of study syllabus has grown to a multi-volume work through this process. When instructors prepared their own, most were three to six pages for a semester, citing reading assignment and explaining written assignments, assuming the context of university study. Each syllabus would be amplified and explained further in the classroom over the semester.

Then came the pressure to move to a minimum standard for the syllabus. I chaired the first committee that did that, and I was happy to do so because I had seen some ludicrous specimens of syllabi first hand, e.g.,

the instructor did not know the name of the unit of study,

the syllabi did not state assignments,

the reading list was a joke,

and ….then there were the bad examples. (Including at least one that boasted of the number of failures there would be.)

From that bad seed grew today’s Godzilla the Syllabus. Its growth was cultivated solely by committees of academics who each year added more and more to the minimum standard. We could not longer assume anything. Each syllabus had to be a complete and stand-alone document. In it every contingency had to be anticipated and provided for, so that no student could later say ‘I didn’t know…’ The last one I did slavishly in accordance with the template was eighteen pages, of which six were mine, and the remaining twelve were generic information about the University.

Now a student who gets four of these tomes each semester, eight in a year, will find repeated in each of them rafts of material that virtually none of them will ever need. The labor and energy that goes into the lists of campus resources, methods of appeal, location of the front door of the library, definitions of plagiarism (revised annually by yet another committee of scholars), and more is never calculated.

We have then a syllabus template that comes loaded with pages of ancillary information, which is all readily available elsewhere. Repetition, repetition, repetition, there is no evidence that repetition reaches anyone but it is something to do. That much of this is now electronic both makes it even more easily available and even less likely to be read.

Each year the relevant committee tweaks the template. It is a standing item on the agenda these days. It does this at a time of its choosing, and what it does depends very much on which Ph.D.s are present with a bonnet full of bees.

The timing is always bad because there are four semester, summer, first, winter, and second. (Though at one time members of a committee objected to the labels ‘first’ and ‘second’ because it would hurt the feelings of someone who started in the second semester to call it ‘second.’ I make no joke here but report the fact with a straight keyboard. What saved the numbers first and second was the inability of the members of the committee to agree on names to put on the semesters. No, we cannot use the seasons since our seasons do not correspond to those of the Northern Hemisphere from whence arrive most of our golden fee-paying students descend, and it would confuse them. And so.)

Inevitably the new template for the calendar year appears a fortnight before the start of the first semester in March. Too late for those who organise themselves in advance of the stampede. Timed perfectly to create traffic jams on unit of study servers and at photocopiers.

Moreover, the tweaking can be minor or major. It is seldom identified, explained, or justified. The instructor is then enjoined to use it.

Because it repeats reams of information from other University offices, there is a great deal of room for discrepancies, because just as the committee is revising the syllabus template, these other offices of the University are also editing their own material. Discrepancies are the inevitable result. A well intentioned student can then find two different directions, one in the syllabus and another on the homepage of the relevant service. Yes, I personally tried using URL links but found even these changed.

It then falls to the administrative staff to distribute, to cajole use, and to record compliance with the template. And then to be the butt of such criticism. Since the administrative staff are professionals they do not reply in kind.

More than once in handing these things out on paper, hoping that it would be read before filing, I saw students, wiser in the ways of the world than the committee that designed the template, rip the last dozen pages off and drop them in the recycling bin on exit.

Is it any wonder that students grow cynical.

I hasten to add that the competitors in committees are always a minority, perhaps a quarter of the membership. The other three-quarters, if they attend meetings at all, are present only in body and curriculum vitae (CV). The only eye contact, the only time I heard the voices of members of this silent majority was when I introduced myself to them. Yet I am sure when came the time to apply for promotion this committee service would have been cited in bold under Service on the CV.

‘Willa Cather: The Road is All’ (90 minutes) (2005)

While marvelling once again at Willa Cather’s life and work in Red Cloud recently, we acquired this video as an aide-memoir. It is as wonderful as the woman herself. There is a very intelligent narration delivered with grace by David Strathairn, punctuated with interviews from critics and scholars.

While most of the talking head spouted the professional cant, a few seemed to be so emotionally attuned to Cather that they spoke in plain English with a catch in the voice. Those are the capital ‘R’ readers to this reader.

The sayers of cant are the sayers of cant, and their careers will flourish as they impress each other, but they have nothing to say to a reader.

Someone who hesitates to speak, who pauses to think, who slowly finds the right words within, and then says them slowly in simple declarative sentences without the blot of jargon, these people I want to hear. The video had several of these Readers.

More important are the readings from passages of her novels through her life as she explored new themes and ideas, but always returned to Red Cloud for inspiration from her formative observations and interpretations.

How a fourteen year old girl could fathom death, as she did, and revert to it more than once, is one of things that makes me think that Willa Cather and her kind are aliens, come to earth to teach us about ourselves.

That she resigned as the most highly paid and influential editor of the most successful magazine, ‘McClure’s’ in New York City, this girl-woman from Red Cloud, because the magazine kept her from writing is quite a story in itself. Be glad she did.

Led by that man of limited ability and unlimited ego, Ernest Hemingway, she is often disparaged by the literati. So be it. Theirs is the loss. Let them sup on the cant.

Her books earned many favourable reviews and a Pulitzer Prize, but more important, millions of Readers.

This film is more explicit about the lesbian relationship(s) than anything at the Cather Center, but leaves open the question of which her friendship with two other women was erotic. (Figure it out, Mr Spock.) All done with a respectful tact. Ergo not done by journalists.

CarHenge: Genius or Junk? (30 minutes, DVD) (2005)

Welcome to Alliance Nebraska, population 8,519, home of CARHENGE.

Carhenge? Just what it sounds like, Mr Spock. It is Stonehenge with cars.

We have seen Carhenge with our very own eyes, and long to see it again!

Alliance and its sister city Chadron (population 5,767), which is about an hour by car due North, were way stations for French explorers and trappers who followed the Platte River. Practice French pronunciation on each: Alliance, Chadron, and Platte, and voila!

This video is an account of the origin, creation, and development of Carhenge, featuring the founder, Jim Reinders, who discovered his home was not his castle even on the Sandhills. There are interviews with townspeople who reacted to Carhenge. Some for it and others against.

I particularly loved the interview with the mayor whose determination to ensure that it is someone else’s problem appealed to me. The first solution was to move the city boundary line a few feet so that Carhenge no longer fell within the zoning laws of Alliance, which laws in turn had to comply with state standards, which have to comply with Federal standards (to qualify for grants and funds, say emergency relief in crisis). So the boundary was moved. Other issues followed about parking, about toilets…..

Some residents objected to this gloried car wreckers yard, as they saw it, as the emblem of the modest little burg. While others saw it, I think, it was hard to tell, as public art to which one must bow. Others heard to slide of credit cards as tourists left I-80 to give it the once over.

Then there were the hoons who vandalised it.

Patiently Mr. Reindeers and his family responded to each assault, verbal, legal, or destructive, and Carhenge has outlasted its critics and despoilers for more than a decade, evolving in the process.

Having read, Jim Work’s krimi ‘A Title to Murder’ which parallels Cargenge to Stonehenge as it figures in Thomas Hardy’s ‘Tess of the Dubervilles,’ I was reminded of Carhenge, and ordered the DVD.

I would like to see the real thing again on my occasional visits to Hastings on the Platte, but it would a major expedition for Alliance is five hours by car. It closer to Denver.

William Davis,’Breckinridge: Statesman, Soldier, and Symbol’ (1974)

John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875) was born to very comfortable circumstances in Kentucky. He was educated at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) where his father had many family members. Upon his return to Lexington, the young John Breckinridge went west to make his name and fortune to Burlington of the Iowa Territory where he was a lawyer to whom professional success came but slowly. Thus he spent formative years outside the slave-holding South.

He was erect, tall, courtly, well-spoken and thus invited to speak at a 4th of July occasion, where he struck the right note and that earned him both more speaking engagements and clients. His law partner, much like that of Abraham Lincoln, complained of Breckinridge spending too much time politicking and not enough lawyering.

By the way, one reason why the young Breckinridge found it easy to leave Lexington Kentucky for Iowa was that a girlfriend jilted him, she being one Mary Todd, later to wed the aforementioned Lincoln.

Though slavery was the issue that governed his life and everyone else’s at the time, he apparently had no particular opinions about it, one way or another. While he was not slaver, he did not oppose it. On every occasion he always sided, ultimately and if sometimes reluctantly, with the slave states on Lockean grounds of the absolute right of property. By the way, religion does not figure much in his life as told in these pages.

Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, the Iowa excursion had always been intended to be limited, and had more success, professional, political, and social in the Bluegrass State. His public speaking on patriotic occasions made his name known.

He served in the Mexican War, where he showed concern for the troops in his command, and learned the need for staff work to secure supplies, food, harnesses, boots, forage for animals, and medicine. These lessons he would use later in life. He also met the whole gamut of officers who would later figure in the Civil War. The list is too long to repeat here, but it included Hiram Grant and Robert Lee.

While in Mexico he defended an officer falsely accused of crimes. The accusation was hatched as a way to undermine the general commanding, Winfield Scott, whose presidential ambitions were plain to see. This was in hindsight a political conspiracy to hamper Scott’s presidential ambitions. But Breckinridge seems to a have taken it at face value. His defence was finely judged and widely reported and successful, giving him a national profile.

His service in Mexico was after the hostilities had ceased but before the treaty was signed, ceding California and New Mexico. Ergo there were still tensions and alarms, but not cannon fire. Unlike all those other Civil War generals, he did not attend West Point, and later learned to be a general on the job.

In the late 1840s and 1850s the Whig Party was destroying itself by infighting, and Breckinridge aligned himself with the rising Democrats. He vigorously campaigned for others, and in time won a seat in the Frankfort legislature. His public speaking is much emphasised. In these speeches he always took a positive tone and spoke about what was necessary, what he could and would do, and made it a point not to disparage his opponent(s). My, my that is lost art, emphasis on the positive.

When Abraham Lincoln visited his Todd in-laws in Kentucky, he met Breckenridge and thereafter they had an occasional correspondence, e.g., when one won a case reported in the press, the other would sent a note of congratulations.

As the Great Compromiser — Henry Clay, a Whig — lost his grip on Kentucky, growing old and frail, and because his party was eating itself, Democrats filled in the spaces available. Became of his attractive personality and eloquence, Breckenridge was pushed to the front. Clay seems almost to have endorsed him, despite the party differences, for they were often seen together.

In the state legislature Breckinridge was a dynamo for local improvements, from schools, roads, bridges, streets, public buildings, and so on. His staff work in Mexico had taught him the importance of detail and he applied this lesson in the legislature, while many others were satisfied with oratory, and though he was exceptionally good at that, he went beyond it to get the details right.

He married but his wife and family seldom figure in this account.

Unusual for the time, he had lived in New Jersey while in college, Iowa as a young lawyer, and being personable, attractive, and sociable, he made friends where he went and keep in touch by mail. His army service added to his contacts and gave him national publicity. As a budding Congressman, both Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas saw great things in him and said so. He campaigned for others in surrounding states.

As a state Legislator and later as a Congressman, he was a mediator. Where there was a deep divide, while keeping his own counsel, he was trusted by all to understand their positions, if not agree with them, and he would confer widely in search of some common ground.

There was only one issue: slavery, masked by states rights and the Constitution. Breckenridge played a key role in the Kansas-Nebraska Act. However much or little common ground Breckenridge could find in the wording of this resolution or that, it was never enough to paper-over the chasm of slavery.

He campaigned hard for Franklin Pierce in 1852, speaking three or four times a day in five states. While his speeches praised the Democrats, he did not belittle nor insult opponents, and generally struck a positive note, which increased the invitations to speak.

Pierce, whatever his merits, became the first, perhaps the only, incumbent president to try and to fail to secure re-nomination by his party. Though Breckinridge supported Pierce for re-nomination, when Pierce was eliminated, Breckinridge turned the eventual nominee, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, who wanted a southerner on the ticket and one who was presentable to all regions, ego he tapped Breckinridge, though the two had nothing in common and had met but once, briefly. (Pierce never forgave him this switch, though Pierce had no chance of renomination.)

In those days the candidates retired to their homes and did not campaign, leaving that to others, and from this practice party organisations emerged. ‘Buck and Breck’ won for the Democrats.

Breckinridge had the same relationship to President Buchanan that all Vice-Presidents have with all Presidents. None.

Though the country was boiling with dissension and the parties were cracking along geographic lines for the first times, the Pennsylvanian Buchanan did not ask the Kentuckian Breckinridge to attend cabinet meetings. Indeed they had exactly one private meeting and that was in the last year of their term about a triviality.

Buchanan was unmarried and solitary by nature. Accordingly, he delegated ceremonial and social tasks to Vice-President Breckinridge, e.g. receiving ambassadors, hosting functions, addressing celebrations, all of which expanded Breckinridge’s horizons and networks.

His main duty was to chair the Senate and he did this scrupulously, unlike most of his predecessors. He was impartial in the chair during heated and intensely partisan debates, but more importantly he spent much time talking to senators before the debates so that he knew what to expect. Ever the mediator, he often was a go-between used by factions and parties to communicate with each other and at times he found that undiscovered country. – common ground to smooth over the crisis de jour. Even that most stalwart and violent Republican, William Henry Seward praised Breckinridge’s management of the fractious Senate for four years. It may be the only time Seward even publicly said a good word about anyone.

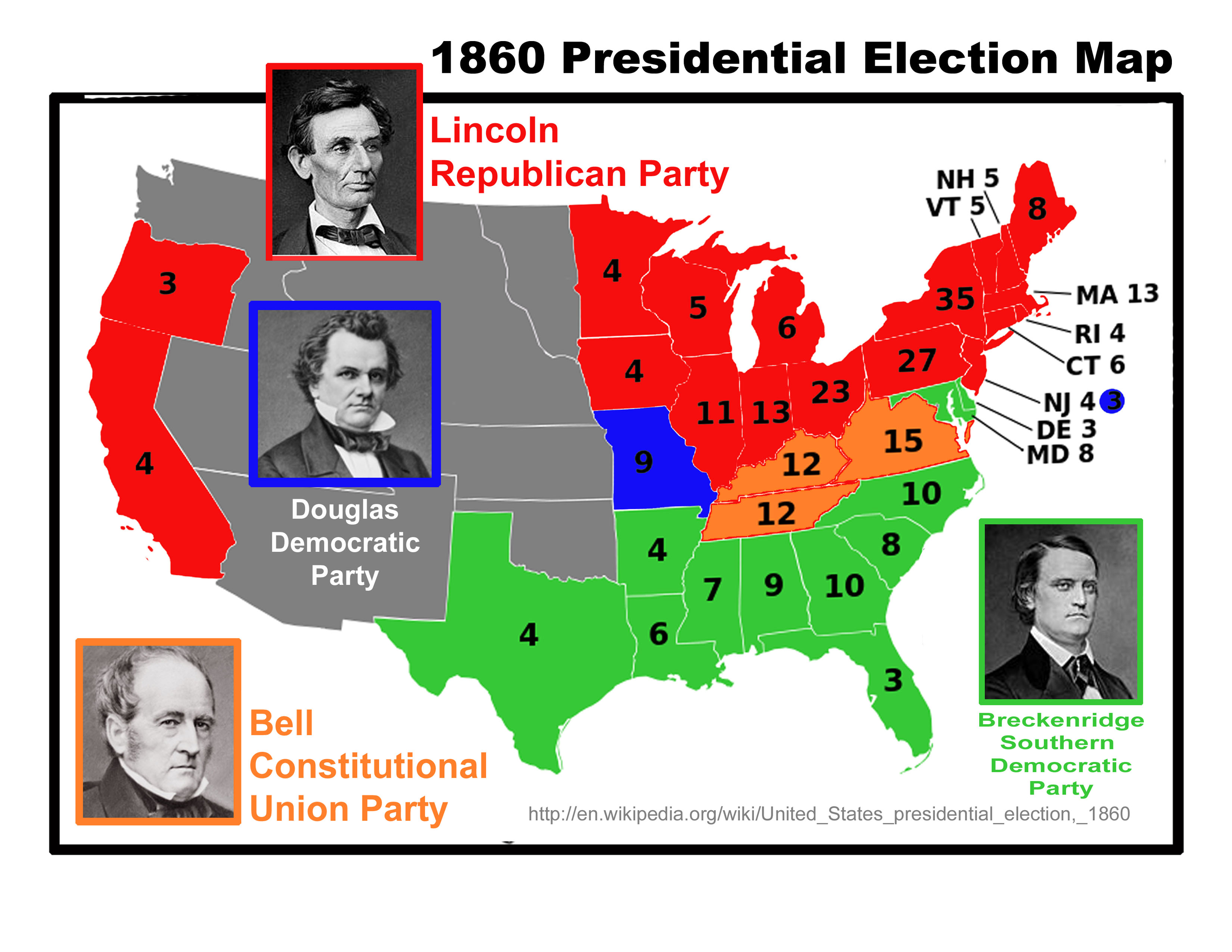

The machinations of the 1860 election are many. The Republicans put up an obscure western lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. The Democrats split along the geographic fault line of Mason-Dixon with Stephen Douglas as the northern Democrat candidate whom southern Democrats distrusted. John Bell became a third party candidate appealing for national unity in the border states like Kentucky, Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri. Southern Democrats nominated Breckinridge, and he accepted. But why?

Splitting the anti-Republican vote would insure that Lincoln was elected, and Breckinridge accepted the nomination precisely to avoid that split. How so? Pay attention now, class, this is today’s lesson.

Once Breckinridge was in the field, the hope was that Douglas would realise he could not win. Then the three candidates — Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell — would meet and agree to withdraw in favour of another candidate and several were lined up, or the other two would withdraw in favour of Breckinridge. Note that Breckinridge did not seek the nomination in the first instance thinking it was inconsistent with his duties as Vice-President. Odd that. But he was certainly flattered to be nominated.

This plan never flew. Douglas made it clear that he would not withdraw and the four-way race ensued. By then it was too late for Breckenridge to withdraw.

The author makes a good point when he lists those who voted for Breckinridge, which include Robert Lee, Hiram Grant, Jefferson Davis, and Benjamin Butler. The point is that Breckinridge was a national candidate, as well as a regional one. He got votes in Massachusetts, Ohio, Virginia, and Tennessee. But it is also true that his vote was concentrated in the South and he carried all the slave state and Delaware, apart from Tennessee, Virginia (both taken by Bell). and Kentucky (ironic that, and shades of Al Gore) which also went to Bell. (Despite 30% of the total vote, Douglas won a majority only in Missouri.)

As the sitting Vice-President he organised the inauguration of Lincoln. He had won election to the Senate and while other southerners left as soon as Lincoln won in November 1960, he stayed after Fort Sumter in April 1861 and even after Manasses in June 1961. He was trying to calm things down but he gave up.

Meanwhile, Kentucky, divided between unionists and secessionists, tried to be neutral as the war started. But eventually Grant’s army crossed the Ohio River to Paducah, and in response a Confederate army entered eastern Kentucky. Breckinridge then returned to Lexington and accepted a commission from the secessionist governor in the state militia. Quite why he went grey and not blue is not very clear. Most of his relatives were secessionists, but not all, but in confusing times that is what he did, and once comitted he stuck it out.

He was now the soldier of the subtitle. He learned on the job, and learned quickly, but he did make mistakes. Braxton Bragg hated him, but Bragg hated just about every other officer in the army.

He served in a variety of places, including Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia. He took part in General Jubal Early’s 1864 raid on Washington DC and his troops shelled Fort Stevens while Abraham Lincoln watched from the ramparts, those two presidential candidates meeting again at this distance during a barrage.

In desperation, President Davis appointed him Secretary of War in early 1865, and he became a statesman again. This part of his career is the subject of another book reviewed elsewhere on this blog, namely ‘An Honourable Defeat.’ Here it suffices to say that it was his finest hour. He did much to bring a lasting peace.

His health was broken by the war years, and when he returned to Kentucky he eschewed public life, refusing even President Grant’s suggestion that he re-enter political life. But he became a symbol of one who accepted the defeat and looked to the future.

William C. Davis

William C. Davis

The book is meticulous and informative. The last chapter offers a very good summary and judgement of Breckinridge’s careers as statesman, soldier, and symbol of the Confederacy best elements.

Gao Wenqian, ‘Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary’ (2008)

Zhou Enlai was a name and face on the news when I grew up, first a menace and then a calming influence. Yet I know next to nothing about him. In English this title implies it is a biography, and so I chose it. Later I discovered that it’s original title in Chinese was about his last years, and this latter title is descriptively accurate. It is an account of the last years of Zhou preceded by a perfunctory description of his formative years. Nothing in the book bears on that phrase ‘perfect revolutionary.’

There is no doubt Zhou was cursed to live in interesting times. In his youth he spent a year as a student in Japan. But he got the political bug and became a lousy student. He then went to France ostensibly to be a student again, but really to join the surprisingly large group of Chinese exiles organising themselves there. It was five years or so. Many people he met there became major figures in subsequent Chinese politics mostly communist. He did not meet, according to this accord, Nationalists like Sun Yat Sen who was in the States, I guess. Nor André Malraux who was in China at the time.

When the Comintern ordered that the Communists cooperate with the Kuomintang (Nationalists), Zhou worked with and got to know others like Chang Kai-Shel and the later Japanese invasion. The Comintern promoted a popular front with the Kuomintang for years, even at the expense of the Communist Party of China. This shotgun wedding only ended when Hitler invaded Russia and distracted the Soviets.

Zhou very soon became number two to Mao, and stayed there for the rest of his life. He was a trimmer, that being the only way to avoid Mao’s wraith. Though the author admires Zhou, there is no doubt that Zhou looked away at some of Mao’s worst excesses including the Cultural Revolution.

Life with Mao seems like Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ to the Nth power.

Most of the book concerns life on the greasy pole in Mao’s China. Mao is portrayed as a paranoid egomaniac who treated people like disposable chess pieces, and who was culpable in Zhou’s premature death. The bulk of the text describes this meeting and that, particularly before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution, all very Orwellian or very like North Korea today.

None of this endless detail fleshes out Zhou the person or deepens insight into him. I never felt I got to know anything about him except that, whatever he thought to himself, he never said, and instead fawned over Mao as the only likely path of survival. It reminded me of reading the memoirs of the elder St Simon who spent eighteen years at the court of the Sun King and who wrote in his compendious and secret memoir that in those eighteen years he never once said what he really thought to anyone, though he talked to everyone everyday all day in the court ritual. No doubt St. Simon lavished praise on Louis but Louis was not as bloodthirsty as Mao.

The book is vague. I will offer only one example of scores that could be cited. The author will say that ‘Zhou handled this problem in his usual smooth way.’ How was that? I would like to know more detail in these hundreds of pages.

Gao Wenqian

Gao Wenqian

The book has too much and too little detail. It has too much detail about this and that plan and plot, the wording of this report or that, and too little concrete detail about what Zhou did that made him so successful and valuable even to Mao. Occasionally the author says Zhou used his usual skill to do this or that. What skill is that? Not enough explanation, e.g., to crush his opponent Mao used the ‘heavy artillery,’ huh, meaning what at a party conference.

So many personalities appear that escape a general reader like me.

The text is both wordy and cryptic. That is, it is wordy and not concrete. I never did form a picture of what Zhou did. The slang-filled translation is no help, e.g., ‘good guys,’ ‘pals,’ ‘hot potato.’ and much more. Though the book is too detailed for a general reader, it is replete with this lazy slang.

Joanna Jodelka, ‘Polychrome’ (2013)

An elderly man in Pozan Poland is found murdered. The more closely the investigating officer, Mariej Bartol, examines the scene the odder it looks. The victim is posed, naked, and almost seems to be smiling despite the strangulation. Then there are the Latin mottoes found on the flower vase, inside the bow of a pair of glasses. Enough to set one to thinking.

Then a second man is found, also posed, also with a few Latin mottoes discretely tucked around the scene.

We get quite a bit of the personal life of our hero, and his mother is some character. But it is laid on with a sledge hammer.

Our hero seems to have been born dumb and misses the obvious a few times.

On the other hand the officers he works with are well drawn, and there is much to’ing and fro’ing in and around Poznan in a wet spring. It has some sense of place.

Then there is the Latin scholar he recruits through his mother’s contacts to make sense of the tags. She is a firecracker from go to whoa, and our hero suffers a rush to blood to his first friend, making him even more slow-witted than usual.

I read it on the Kindle and it was not easy. There were odd font characters, broken lines, run-on paragraphs, spelling errors, and more. The translator into English seems to be a Pole, and I guess that explains the syntax errors and the unfathomable idioms which may make sense in Polish but do not in English. Maybe the translator once worked for Jimmie Carter. (Either you get it, or you don’t.)

Joanna Jodelka

Joanna Jodelka

Before trying another one of these I would want some reassurance that editorial improvements had been made. On Amazon the paperback is $0.08 which is less than the Kindle version. Not sure what to make of that.

It is a double whammy, a lousy presentation and badly translated. It was too much like reading student essays. There were students of my acquaintance who thought that if the work they submitted was incomprehensible, then the instructor — moi — could not fail it. WRONG! They would then challenge me on the ground that their paper was…, yes, incomprehensible, and since I did not therefore comprehend it, I could not honestly fail it. Imagine the time I spend in such conversations. Now it is easy to see why retirement has its attractions.

For what is worth and to balance the books, I had more than one similar conversation with a Ph.D.-bearing lecturers who asserted, no evidence required, that their lousy teaching stimulated students to learn for themselves. This was no argument about the meaning of lousy teaching, they admitted it and celebrated it. Needless to say these individuals all prospered. What did I say about retirement?

The Bette Davis Club (2015) by Jane Lotter.

Or, Margo’s adventures through the money glass. Reluctantly, Margo goes to the wedding of her niece, and the fun begins in Hollywood. The spoiled bride bolts, and the vampire mother of the bride makes Margo an offer she of near bankruptcy cannot refuse and a black AMEX card! She throws in the keys to a red MG and the groom! Who knew such cards existed? Not us plebs.

Off they go down Route 66 meeting all kinds of people, some of the most memorable at the Lesbian dance contest in Palm Springs, others with whom they exchange insults over breakfast, a kindly woman who presses a marriage manual on Margo, and Boone who seems destined to be in recovery from head injuries. He should have stuck to football.

Cary Grant even puts in a cameo appearance,. This book has it all, and more!

Finding the bride, after all this, is anti-climatic. She is a brat.

Margo’s confession at the meeting set a new standard. Indeed. No spoiler here. Find out for yourself.

Along the way the imbecilic nature both of Hollywood and its audiences are noted.

Margo is wrong about almost everything but soldiers on. She may be broke but it is not from a lack of effort.

It shifts gears from silly to serious and back several times but the mix is well judged.

Jane Lotter

Jane Lotter

I was very disappointed to learn it is a once-off.