Walt Disney was born in a small railroad town in Missouri. It was a water stop for trains, and he retained a lifelong fascination with trains which led to Disneyland.

He was a bright and industrious young man who had seen too much farm work as a boy to want to be a farmer. In his desire to escape the physical drudgery of farming he is akin to Huey Long.

His distinction in the early animated cartoons was the effort to put emotion into the toons. Whereas rivals like ‘Tom & Jerry’ or ‘Felix the Cat’ were drawings whose heads exploded and then re-assembled, Disney started putting puzzled or hurt expressions on the face of Mickey Mouse.

Walt Disney never stood still. He went from one project to another. He was a workaholic and worked late into the night, even when he was the proprietor of Disney Studios, he was frequently alone in the Studios at midnight.

He was also an innovator and a demon for ever higher quality in drawing, animation, movement, colour, and more. Innovation and quality meant that animators wanted to work for him, and many left higher paying jobs to work at Disney Studios to learn more of the trade. One of his innovations was staff development, as we would call it today. The author also credits Disney with the concept of the storyboard, now used in every movies industry in the world.

He could be volatile. There are many claims that he was tyrant or a racist but this author finds no evidence for either claim. Though the swings of business meant that at times, loyal and able staff had to be dismissed because there was no money to pay them. He was categorically anti-union and paternalistic as an employer. He equated unions with communism as did too many others during the early days of the Cold War, and he was a friendly witness before HUAC. Yuk!

Despite the temptations of Hollywood he was ever loyal to his wife. The author implies that Disney broke profitable business relations with some actors and directors whom he thought, perhaps wrongly, did not treat her with respect. After their first child she had several miscarriages and that led them to adopt a second child.

His brother Roy ran the business side, but always deferred to Walt’s creativity. When Walt used company money to build a scale model train as a hobby, Roy did point out that the stockholders would not accept that. To justify the scale railroad it became a company project, and led to Disneyland.

Roy Disney

Roy Disney

Disney visited many amusement parks and found that those aimed at children bored adults and those aimed at adults bored children. In both cases the boredom meant a short visit. By combining amusements for both adults and children, the visits would be longer, and patrons would spend more money. To facilitate longer visits and more spending, Disney introduced suff development to train guides, operators, vendors in dealing with customers. Another Disney innovation is queue management.

I was surprised to learn how fragile the Disney empire was even in 1960s when it seemed to be an American institution second only to the White House. Since Walt was always pushing ahead to another project – more and better cartoons, television, movies, Disneyland, Disneyworld, EPCOT (which is not mentioned in this book), the finances were always stretched. One sign of this is that the brothers Walt and Roy lived modestly compared to the Hollywood standard of the time.

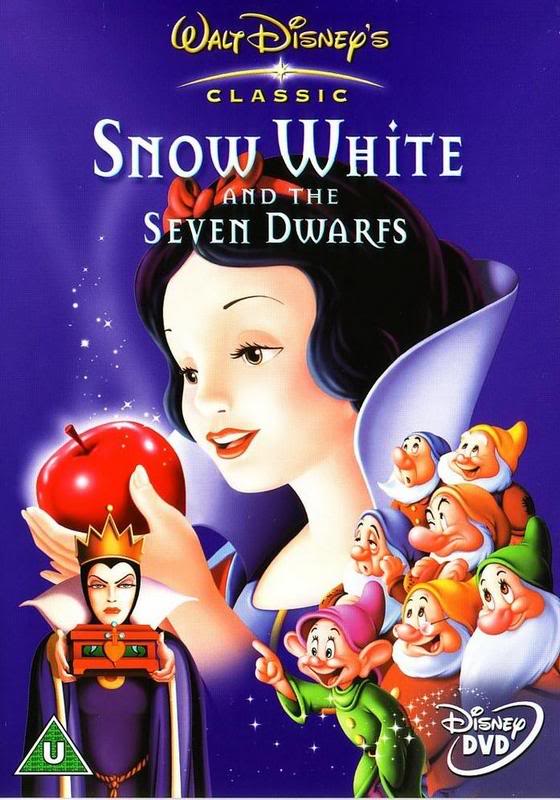

‘Snow White’ (1937) made mint and set a standard that he never equaled. The single-minded determination to make a feature length cartoon, and to make it an artistic and commercial success is one of the most interesting episodes in the book. The banal description of ‘Snow White’ on the InterNet Movie Database belies what a groundbreaking work it was in 1937.

Disney set out to top that with ‘Fanastia’ (1940) but the technical problems were so great that this project devoured money, and in the desperation to get a product and some financial return, it was neither an artistic nor commercial success. Disney did not always get it right.

Disney made the transition from cartoons to live action films thanks to World War II. When the war began the Department of Defense contracted Disney Studios to make training films, which were at first technical, involving a lot of diagrams and animation, but came to involve actors showing how to repair an engine, or repair a tank tread.

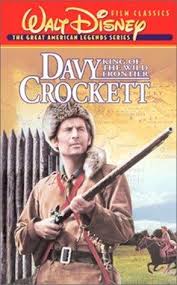

‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ (1954) and ‘Davy Crockett’ (1955) both made money and attracted acclaim. Genius as he might have been, Disney did not follow-up either successfully. He was always reluctant to hire expensive Hollywood directors and actors and ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ is the only time he did. When ‘Davy Crockett’ made even more money, he decided he did not need high priced talent. I do remember that cap!

He seems to have misunderstood the success of ‘Davy Crockett’ because he then cast its star Fess Parker in a series of duds. They were duds because, in effect, Parker was cast as a supporting actors to, by turns, a group of children, a dog, and a bear. When his contract came up for re-newal, Parker quit.

By the way, he picked Parker out of the film ‘The Thing’ (1951), and as an unknown, Parker came cheap.

The 1950s and 1960s television series of Disney was designed to promote Disneyland.

There was a lot of office politics in Disney Studios. Getting his attention was key but he had so many projects going, including constantly rebuilding and expanding the studio that his attention was scarce.

He travelled a lot in the States but also in Europe. The honours and awards poured in but he remained restless for the next project.

There is a good deal in the book about the technical aspects of animation. More than I expected in a ‘Life.’

MIchael Barrier

MIchael Barrier

Michael Barrier played Lieutenant De Salle in Star Trek, the Original Series episode ‘Memory Alpha.’

De Salle

De Salle

Skip to content