This is the eighth title in the adventures of George Sueño and Ernie Bascom, Crime Investigators, Military Police, United States Eighth Army, South Korea in the 1970s when the Cold War was often very hot. Sueño is the thinker of the two, while Bascom resolves most problems with his fists and sometimes with an illegal hand gun.

Having read the previous seven titles over a number of years, I had noticed that North Korea never figures in the books. The villains are inevitably Americans and South Koreans in some combination. Not so in this title. The setting is North Korea.

Sueño has agreed, for reasons of his own but as always involving his first friend, to go into North Korea undercover. Whoa! How can this 6’ 2” American G.I. go undercover in North Korea! Limón contrives some pretty clever ways and means to explain that. They hinge on (1) the isolation of North Korea and North Koreans from the wider world and (2) the tyrannical nature of the regime.

Because North Korea is so isolated, North Koreans, even North Korean police, reason from the propaganda stereotypes the regime has drummed into them for thirty years at the time of the story. Americans are blond-haired and blue eyed with enormous noses. Sueño is a Latino, big, yes, but dark with a cute little nose.

In this tyranny every mistake and failure is greeted by maximum punishment. Not only will the erring official be executed but so will be two generations of his family, his parents and likely his in-laws as well as his own children. This terrible possibility is around the corner for anyone. Just read the news today to realise that is still the practice. Consequently, no one reports anything if it can be avoided, because there might be a mistake. The best way to avoid mistakes is to do nothing. Sueño trades on this reluctance to admit trouble.

He has some tenuous contacts in the North who, also for reasons of their own, cooperate. That standard trope is vividly realised in the case of Kang, but credulity is stretched. Kang gets away with too much and is too conspicuous for the suspension of disbelief. He leaves a trail behind him even Dr. Watson as played by Nigel Bruce could follow but no one is able to follow it. Go figure.

Now inaction may be the safest course, but safety is not guaranteed so the North Korean black market offers a service to officials who realise something is wrong but do not wish to report it through channels. They can hire unofficial fixers who will solve the problem for them without leaving a trail. These fixers are often police officers moonlighting, and in these unofficial investigations they are even less constrained than they would ordinarily be though they, too, have to be careful to cover their tracks from their own superiors, usually by splitting the profits and glory.

The portrayal of North Korea in the book is, to say the least, Orwellian. There is the chanting of slogans of praise to the Dear Leader. There is the robotic obedience to imbecilic commands. There is the starvation of most people amid the lavish luxury of the elite. It is enough to satisfy even Ted Cruz.

Kim Il-sung

Kim Il-sung

Sueño’s cover is that he is a Peruvian sailor with the papers to prove it working on an Albanian ship distributing and collecting cargo along the west coast of North Korea.

That he understands and speaks Korean from long study during his many years in South Korea gives him a double advantage. The first advantage is that he understands what he hears and reads. This advantage is multiplied by the second advantage which is that no North Korea can believe a foreigner understands, still less, speaks Korean. They have been told for so long how unique and special North Korea is, and how barbaric and backward the rest of the world is, that a foreigner is barely human in the eyes of most. In his private moments Sueño compares that attitude to the disdain Anglos showed him when he grew up Latino in East Los Angeles in the late 1960s. It is the same at bottom but it is magnified a thousand times in North Korean.

The plot is, well, fictional. Spoiler alert! The conceit is that a division the North Korean army wants to overthrow the Government of Dear Leader but needs the help of the US 8th Army to do so. Sueño is supposed to convince the 8th Army to hand over fuel, medicines, food, ammunition, and weapons to this division to enable it to do so. Huh! A sergeant is going to convince the 8th Army Command to risk starting a war by violating the DMZ, and in so doing will tell the South Koreans what? Pointless from the get-go.

I have not mentioned the action man Bascom because he did not figure in this book, and I find that is something of relief. In the last title or two I have read in this series I found Bascom’s adolescent temper and libido getting on my nerves.

As always with these books, the place and period are superbly rendered. There are no jarring anachronisms or cultural slips. The characters are each distinguished by speech and attitude, as well as appearance. There is no pointless description of clothes, rooms, or food that pad out so many tedious krimis.

Martin Limón

Martin Limón

When I taught a semester at Korea University in 2004 the director of the Korean Studies Department told me that a reunification of the Koreas was inevitable and would be catastrophic for all concerned. He meant that it would happen one day, and when that day came no one would be able to moderate, slow, temper, channel. or resist it. He also meant that the regime in the North was fragile and could shatter at any time, probably due to starvation. Finally, he meant that the people in the North were creatures of the regime in a way that East Germans were never creatures of the DDR. This last is the most interesting and telling point.

The isolation of North Korea has been much more complete and effective than that of East Germany. East Germans were exposed to radio and television, first from other Warsaw Pact countries and through them to even more sources. In East Berlin they could literally look into the Western World. There was also exposure at a personal level in East Germany through visiting tourists from the West as well as other Soviet Allies. Most East Germans could get West German television programs at home if they dared to adjust their sets. And so on. There were many cracks in the walls around East Germany. Not so North Korea.

The jamming of radio and television and the language barrier to Chinese and Japanese precludes the taint of the airwaves. The kind of punishments dished out routinely in North Korea would discourage anyone from adjusting a television set, not that anyone in North Korea owns one. That is the most important insulator, the poverty and ignorance that the population is kept in. Foreign languages are not taught in part to block contact with foreign ideas and practices. They know nothing of the rest of the world but what the regime says.

Integrating the two Koreas would be far more difficult than integrating the two Germanies. The North Korean regime would have many diehard loyalists, and not just from the elite, who would not readily forsake it. There would be no comparable flood of North Koreans willingly leaving North Korea for the South as East Germans flooded from East Germany to West Germany overnight.

The North Korean regime might collapse due to starvation or a palace coup but then nothing might happen, no one would move. The pressure on South Korea to act would be great, largely from its own population but if South Korea entered the North, even bearing food, there might be armed, if disorganised resistance…. a grim picture, the more so when nuclear weapons are available.

Author: Michael W Jackson

Väinö Linna, ‘Under the North Star’ (1959)

One of the classic sagas of Finnish literature detailing life in a village in the period 1884-1907 as a microcosm of Finnish history of the period, which I read as homework for our planned short visit to Helsinki in September 2016.

It is earnest and documentary in style. We start with Jussi who works hard as the handy man at the parish manse and in his spare time drains a swamp, and with the verbal agreement of the vicar farms it.

All readers know, as Jussi suspects, that the verbal agreement will be insufficient when tested.

Much of the book is like this. It sets up situations that any reader can see unfolding.

The message is clear, the underclass always takes it on the chin, and the underclass is always Finnish, and even if the overclass is, in the village of Pentti’s Corners anyway, Finnish they hold the position because of Russian suzerainty of the Grand Duchy of Finland.

The language politics pervades all. The old vicar preaches in Russian and consoles the bereaved in Finnish. The local newspaper is in Russian. Finns are seldom permitted to speak Finnish.

Legal questions, like Jussi’s informal tenancy, are adjudicated by Russian law, not Finnish practice. Nor even by the rules of John Locke, i.e., ownership going to those who mix their labor with the land, which in this case would by Jussi.

A young vicar replaces the old and in time the pressure on his young family is resolved by encroaching on Jussi’s farm. The vicar’s wife is the source of this pressure, and she is a cardboard cutout for this role.

Indeed, none of the characters are rounded. Jussi is nearly a robot, who works all day and all night. Though he is credited with the vision to realize the swamp could be drained and farmed, that seems to be limit of his imagination, and that limit is enough for the plot. A little too pat, I thought.

Likewise, the other characters stereotypes from many other such stories, the talented and handsome workman who prefers to lay around scheming his next seduction, the vodka soaked doctor, the fiery tailor who speaks a garbled version of proto-Marxism from Georgi Plekhanov about the masses, the timid newspaper publisher who dares not print a word of Finnish for fear of losing the licence to publish.

The Japanese defeat the Russians in the Far East, and though not a word is said of it by any official source, and not a word published about it, still everyone in this remote village knows it. Yes, I know about rumour mills, but really, most of the unschooled people in the village Linna has conceived would have no idea of the Far East or Japan.

There is also political unrest in Helsinki, including an assassination. While this is closer to home, it is still an alien world to the villagers, whose major worry is retaliation from the Russians. Rational as that is, it also seems a long bow for these rough, uneducated villagers to see cause and effect in this way with the goings on in distant Helsinki where none of them, and no one they know, has ever set foot.

The tailor Halme agitates and the vicar counsels patience. Those locals who are aware of some of the wider world suppose that if the czar only knew how badly the Finns were treated, then he would change things. This is the old Russian folk maximum, perpetuated by every czar. The bad comes from corrupt ministers around the czar, that insulation that kept the Romanovs in business for the last hundred years. (Spell checker note: ‘czar’ is a difficult word to get through the spellchecker. It would prefer tsar so I stubbornly persisted with czar.

When Russia revoked its commitment to a Finnish Constitution, there was a reaction in Helsinki and nationalists adopted some proto-Marxist rhetoric to organised resistance. Some of the youths who resisted were exiled and made it to Queensland in northern Australia, as chronicled in the novel of Craig Cormack ’Kurikka’s Dreaming’ (2000). Russia itself was undergoing severe strains at this time, too.

Marx was right and Plekhanov was wrong, by the way, and the villagers do not arise to seize their the fruits of their labor. Although Jussi’s son Akseli becomes a convert to socialism and that makes him a marked man. While there is no general strike, but there are plenty of strikes here and there. The natives are indeed restless and Halme continues, making suits for the squires, while agitating for a mix of nationalism and socialism, one does not dare say national-socialism any more.

There are divisions among the Finns who are united by nationalism and divided by ideology. Numerous variations are traced in debates, speeches, rallies, and confusion.

The first time the people of the village see a Russian, he comes to nail up a notice filled with threats. Not a public relations master stroke. This followed shortly thereafter by evictions enforced by mounted police who are Finns but labeled Cossacks. It is a common motif that overwhelming force will shock and awe the restive into submission, and it never works, leading to ever more force, as it does in these pages.

Though I found the novel stiff and wooden, it is also true that the author knows the way of life of the people he depicts better, say, than the social realist writers in the United States covering the same period. I have in mind Theodore Dreiser, Frank Norris, and Sinclair Lewis. There is in Linna’s pages none of the condescension that Dreiser, Norris, and Lewis unwittingly reveal while representing the downtrodden. While loud in denouncing the oppressor such writers have no empathy with the oppressed. Their reaction is intellectual, learned from the pages of books. Linna’s voice is much more authentic than any of these three.

There is no redemption for the novel in the descriptions of that north star or nature and the place: these are mechanical. I found only one playful mention of Swedish, albeit I was turning the pages very fast, but ethnic Swedes remain to this day, an exclusive caste in Finnish society, as evinced by the Finnish literature written in Swedish.

Väinö Linna

Väinö Linna

I glanced at the many laudatory reviews on Good Reads and found nothing in them to give me pause. This is volume one of a trilogy and I think I will leave volumes two and three to all those accoladers on Good Reads. Serves them right!

Madeline Miller, ‘The Song of Achilles’ (2013)

This is the story of the boy Achilles and lifelong companion and true love Patroclus from their first meeting when both were eight, told from the point of view of Patroclus and set in a mysterious world. It is ‘mysterious’ because the gods are ever-present. Max Weber said the Enlightenment had gradually ‘demystified (Entzauberung) the world,’ that is, taken the mystery out of the world through rationality and science. Well, this novel is firmly set in a world that has not been demystified. The author handles both the gods and the men and women and the goddess, if that has to be said, quite well, and also their interactions. The prose is gorgeous and the conceptions of the principals is engaging.

I made the remark about goddesses because anyone familiar with the mythology knows that Thetis, the divine mother of Achilles, was one formidable goddess. Even the the king of the gods, Zeus, had been known to steer clear of her.

Patroclus is a foundling who pitches up at the home of Achilles’s mortal father, who takes in boys as future warriors. In a world ruled by the sword this is a wise precaution.

We visited the site of Troy in October 2015.

We visited the site of Troy in October 2015.

The view of the Trojan plain.

The view of the Trojan plain.

The descriptions of Achilles from boy to man are, well, Homeric, it has to be said. He is beautiful, he is graceful, he is simple in manner for there is no need for him to prove himself to himself or to anyone else, his senses are preternatural… he may work all day with sword and spear in practice and yet never seems to sweat. The abrasion of his hands on sword haft never raises a callous, and so on. Truly he is favoured by the gods.

The more so when Thetis appears, as she does, now and again and when least expected. The first time she appears to Patroclus, of whom she disapproves as unworthy to be a companion of the god-born Achilles is marvellously realised. (Ditto the last time.) The boy is walking along a mountain path when he realises all has gone quiet. The cicadas have stopped. The birds have left the sky. Even the leaves on the trees are still. The grass itself seems tense in expectation. And then…there she is, a combination of incredible beauty and searing hatred. To look at her burns his eyeballs, when she looks at him, his skin burns. Not a goddess to cross.

Though Thetis hides Achilles to spare him from the Trojan War, the wily Odysseus finds him. That is another story and it is partly re-told here afresh. She hid him among a large group of girls in female attire. Suspecting that Achilles was among these girls, Odysseus threw down a sword before them and the hand that snatched it up with blinding speed, that was the hand of Achilles. He was born to hold that sword, a reflex to grab it. The story is dressed up a little here but stays entirely faithful to the legends. Odysseus used some good old fashioned leg work to find the place where Thetis had secreted her darling boy before he got close enough to drop the sword.

There are some soft spots in the story. It is never clear to me why Achilles took up Patroclus. Achilles is asked this very question a couple of times and answers each time, but none made sense to this reader.

I also found it hard to reconcile this mild mannered Achilles with the butcher he became at Troy. Though the novel does deftly lay the groundwork to explain his double reaction at Troy, first to the loss of the girl Briseis to Agamemnon and then Hector’s murder of Patroclus. Though, strangely, regarding Briseis the author does not quote what Achilles says in the ‘Iliad,’ ‘I love her.’

Yes, Achilles knows the doom that hangs over him, and in time Patroclus learns it, too. But there is a shred of hope even amid these Western Front trenches at Troy, for the prophecy says that as long as Hector, the Trojan champion lives, so shall Achilles, i.e., Achilles will only die after Hector. Since Hector seems indomitable, Patroclus has hope that Achilles will survive, somehow. Patroclus is not a deep thinker.

Achilles faces his destiny and wades into the mayhem at Troy slaying this one and that by the dozen. He moves at five times the speed of even the most athletic opponents. Patroclus, never much a hand at athletics or warfare, stays clear of the fighting and becomes a healer, and there is much to heal. This I do not remember from the ‘Iliad.’ But the author made a choice for reasons of plot and character. So be it.

More than once ethical and moral matters rise to the surface, and are discussed by characters. The writer manages to do this without anachronism, not imputing to these men and women our Enlightenment ethos, nor condemning them for lacking it. Quite an achievement, this. Those that have not read the ‘Iliad’ do not realise how philosophical is that poem of force.

But fate is fate, and bad leads to worse.

Madeline Miller is a high school teacher.

Madeline Miller is a high school teacher.

The novelist clearly shows that, to a degree, even within the ambit of the prophecy, Achilles is the author of his own fate. That is an achievement. Chapeaux!

Stanley Buder,’ Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning, 1880-1930’ (1967).

When doing homework for our trip to Chicago I came across reference to Pullman railway cars, a fascinating business model in itself. Those references also mentioned George Pullman’s artificial community, the eponymous Pullman. It was time to find out more.

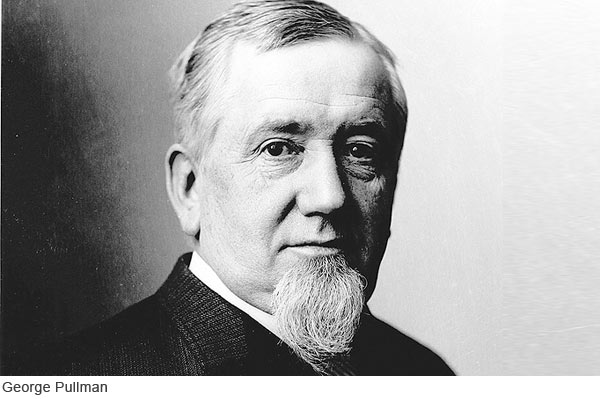

Pullman made a fortune from the railway cars that bore his name from 1867-1968.

George Pullman.

George Pullman.

As railroads were rebuilt after the Civil War and extended coast-to-coast, Pullman built ever more of them and had to expand the manufacturing capacity. Because in his business model the staff of the cars was also contracted with the cars (of which he always retained ownership), he also had to recruit and train staff to maintain the Pullman standard. To do so, he bought more than 4,000 acres south of Chicago and set up a new factory and built a town around it.

To recruit first class mechanics (the term that applied to all skilled workers in his factory), to ease the commute of workers who lived in Chicago, and to satisfy his philanthropic self-image he built a community for his workers called Pullman, after the factory, not after him personally in the first instance. It would offer all the necessities and conveniences of town life from clean water, sanitation, paved streets, schools, libraries, theatres, and so on, all laid down in a plan and built before the first inhabitant moved in. There were would be no demon rum, no gambling, no prostitution and related vices.

The dwellings were varied in size and the occupants rented them from the Pullman Company at a rate calculated to return 6% on the investment of building and maintaining the community, that being the return the Pullman Company realised on its other investments. This return was important because Pullman wished to prove to other robber barons that such social investment was profitable. The author found that it never did quite make 6%, more like 4.5%, something that the Pullman Company kept secret.

Pullman employees had first priority for the housing, but some others also rented there though not many because there was nothing there but the Pullman factory in the early days. The homes were subject to occasional inspections to identify maintenance needs and to insure that the occupants were taking care of them. At first the rent was extracted from salaries before they were paid, but a court struck that down in a class action. Nonetheless when paid, Pullman employees could not leave the pay desk without paying the rent.

What’s so good about utopia? The town of Pullman offered peace and quiet, recreation for families (parks, theatres), libraries and schools, sanitation, clean water, fuel, and the like, all laid on. It was run by a business manager because it was unincorporated. Ergo the residents had no say whatever in what happened. Moreover, their residential tenure depended on the Pullman Company. Furthermore, they could never buy a home there. By the way, the community included a covered market but Pullman did not have a company store, but rented space in the market to providers.

It is a kind utopian thought experiment. One can have all these good things of life in return for giving up democracy.

George Pullman was no friend of democracy, having observed at first hand its practice in the 1850s and 1860s in Chicago where one corrupt political party replaced the other by turns with mayors and councillors each more venal than the other. The corruption at city hall, ensconced by the democratic process, was matched by the drunkenness, robbery, assaults, prostitutions, and drug-taking on the streets. One neighbourhood of two thousand residents had forty bars and fifteen brothels, and more. Ruthless landlords built tenements and extracted maximum rents for rat-infested hovels. Despite the taxes collected, the streets were mud baths with plentiful horse droppings. Schools and libraries were private with stiff fees. But here was vigorous democracy as the parties battled each other in the race to the spoils. The corruption included wholesale vote rigging. Some things have never changed in Chicago. There has always been a high turnout of voters there, especially among the dead who do not care for whom their vote is cast.

To most residents of Pullman and to the journalists and philanthropists who visited the town, it was superior. ‘To most’ but not all, because some railway workers wanted to extend the union to Pullman workers to secure higher wages and to increase the security of tenure in the homes they rented. There were occasions when workers who did not meet the Pullman Company standard of punctuality, sobriety, and good work were evicted from their homes overnight. In least one case the activities of a worker’s wife caused eviction. (Use you imagination to figure it out, Sherlock.)

George Pullman reacted to these union stirrings as a personal affront to his benign paternalism. There would be no negotiation; not an inch would be given. Cometh the fall.

The railroads were the site of much of the early struggle for unions, often led by the redoubtable Eugene V. Debs. I have discussed a biography of Debs elsewhere on this blog.

At the same time the ever-expanding city of Chicago, doubling in population every ten years, was encroaching on once distant Pullman. In time Chicago incorporated Pullman into Cook County though leaving the domination of the Company largely intact for another decade.

The collision course was laid in. The Pullman Company paid high(er) wages to attract and keep good workers as well providing all of the amenities of Pullman town for them and their families. But it was a business and when competition undercut the Pullman Company it unilaterally reduced wages while leaving the rents at the established level to get that 6% return on investment. When demand was high it expected unpaid overtime out of corporate loyalty. When the bottom fell out of the demand, the Company laid off workers and if they could no longer pay the rent, then they were evicted. The union movement found increasing interest from Pullman workers. By the way, Pullman did retain employees and sell cars at a loss at times before laying off staff. But the layoffs came.

The very kind of workers that the Pullman Company wanted, these were those most likely to chaff at the control of their lives and fates in Pullman Village. They were safe, sane, sober family men who would aspire to home ownership, who would want an education for their children and taken an interest in it, who would want a social life for the housewives, who would want family entertainment, who would want and expect job security. But George Pullman would never relinquish control of anything he owned, not one iota.

The result was the Pullman Strike that went from bad to worse. While the workers offered negotiation, the Pullman Company quickly resorted to force, and was shocked to find resistance. It spiralled out of control amid much posturing. Debs called every calamity a victory. George Pullman affected wounded pride. President Grover Cleveland sent in 12,000 Federal troops, three for every striker. (President Cleveland currently ranks in my book as the worst incumbent.)

The overkill of the corporate and political oppression galvanised public opinion against the Pullman Company. Religious leaders, newspaper editorialists, and even Chicago businessmen blamed the Company, not the strikers. George Pullman found himself ostracised among the business elite and that made him more stubborn. It became a test of wills, one he lost.

In the long aftermath, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the Pullman Company must divest itself of the town. The annual Labor Day holiday in the first week of September was one of the concessions to the union movement from this strike.

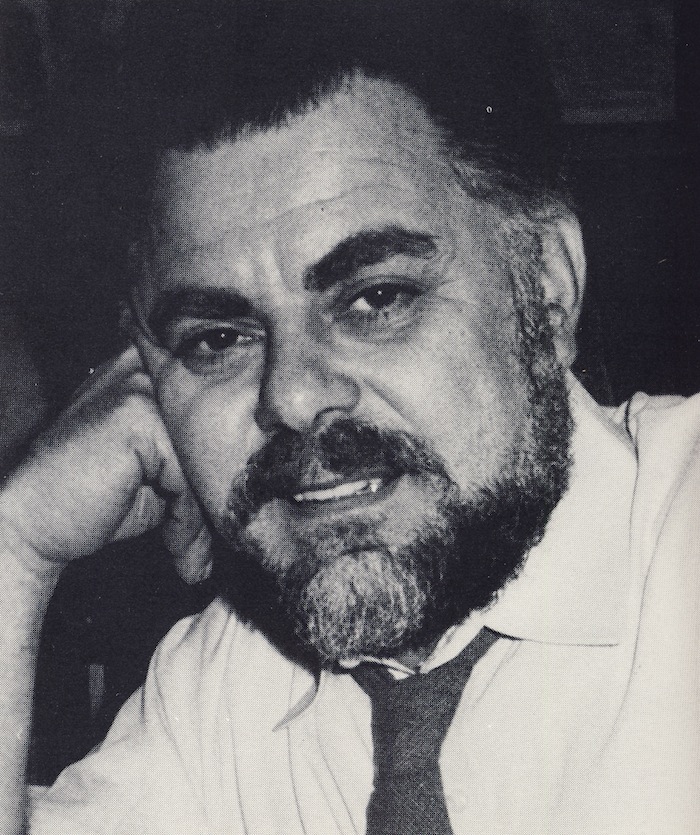

Stanley Buder.

Stanley Buder.

After a hiatus, the Pullman Company survived but was never the same again.

Nothing is said about race, but many members of the over-the-rail staff of Pullman were black. There is much else in the book about the business practices of Pullman which I found of interest. For that, read the book.

Stephen Hess, ‘The Professor and President’ (2015)

A memoir of sorts from the two years in 1969 and 1970 when Daniel P. Moynihan, with Hess as his deputy, served as President Richard Nixon’s chief advisor on domestic policy.

It was the odd couple: the president was a social conservative who courted to the right wing of his party to get the nomination and then moved further right to win the election joined with a high profile exponent of liberalism in American politics. Nixon ran to the right in 1968 first to secure the nomination from much more liberal Republicans like Charles Percy and that Hamlet of the Hudson Nelson Rockefeller. Then Nixon ran even further toward the right to undercut segregationist George Wallace’s independent campaign among those red of neck. Each time the message was simple and clear: law and order, cut welfare to zero, wind back the clock on affirmative action, stop integration by ending funding for its support, stack the Supreme Court with non-entities who would deny government intervention to support minorities…. That was rhetoric. It has a strangely contemporary ring to it, does it not?

In office the reality was this. Nixon wanted peace and quiet in the United States and he personally wanted peace and quiet in the White House. He was willing to buy domestic peace and quiet. Moreover, Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and seemed secure in continuing that. Nixon saw no reason to rile up Congress on domestic matters that he, Nixon, did not care about, nor to stir up the population by eliminating programs that had popular support. None of this could be done overtly for fear of alienating his electoral constituency which he would need again in four years. It was time for some legerdemain.

Enter Pat Moynihan. His credentials as a liberal in American politics were unassailable. He had worked for President Kennedy. He had advocated the cause of minorities. He supported all manner of social programs. His intellect was bright and he was a wordsmith, and he had other credentials, too, as a Professor at Harvard University. Robert F. Kennedy was dead, but Moynihan was his living spirit still flesh. Moynihan embodied from the bow tie on the Eastern Liberal Establishment that Nixon hated privately almost to distraction.

But it would placate Congress and confuse and perhaps divide his critics if he keep Moynihan close, and so Nixon appointed him as the chief domestic political advisor with cabinet rank. It was a masterstroke that won much breathing space for the new Nixon administration.

At the outset it seemed that Nixon’s administration would be dominated by two Ivy League professors, since his chief foreign policy advisor, appointed earlier, was Henry Kissinger, another Harvard professor, head of the National Security Council with cabinet rank. Remember that Kissinger had entered public affairs with Nelson Rockefeller, the most liberal of the Ripon Republicans (a phrase no longer used by the Grand Old Party). Are these two twin and each a deuce philosopher-king?

One of the interesting observation in the book under review is the comparison of the communities in the White House for domestic and foreign policy. While foreign policy is the preserve of the President, per the Constitution, and only two agencies figure in it, though they are the great and good Departments of State and Defense. In fact, with the appointment of Kissinger and the elevation of the position of Director of the National Security Council to cabinet rank, Nixon enlarged the foreign policy circle. It was still, however, a small circle. All the principals could sit around one small table, and a single strong personality could dominate the group, in this case Kissinger, even though he did not have the powerful Department of State and Defense at his back, he had the intellect and cunning to out manoeuvre them to influence Nixon. But that is another story.

In contrast the domestic policy community is vast and ill defined, but it starts with every other cabinet member, fifty state governors, and expands from there.

Moynihan saw an opportunity to dominate the domestic policy community with his own intellect. It would be a contest on two levels. The first was to get Nixon’s attention to domestic policy and the second was to displace his principle domestic policy rival, the economist Arthur Burns. The first step was simple and easy and had continuing implications. It comes down to real estate.

Thousands of people work in the White House and it has long since burst at the seams. Nineteenth Century broom closets have been converted to offices, hallways reduced in size to enlarge offices to shoe horn in more people, doubling and tripling up is the norm. The alternative was the Executive Office Building nearby. Moynihan opted to squeeze into a White House broom closet a few steps from the Oval Office, while Burns chose an opulent suite of rooms in the Executive Office Building. That was very nearly end of story. Game, set, and match to Moynihan. He was at hand instantly, and he made use of that.

In a way that says it all. The imperceptive Burns probably never quite realised it was a competition, and conveniently excluded himself. He further reduced his own influence by his ponderous class room manner. He could not participate in discussions ad lib. He could not debate submissions and never got to the point, if ever he had one, in less than forty-five minutes. If asked for comment in a meeting he would go away and write a lecture to deliver a week later. It was no contest. Nixon, in fact, began to interrupt Burns to ask for the conclusion, and then simply stopped inviting him to meetings. Moynihan excelled at debate and was always ready with an idea.

Getting Nixon’s attention was harder. The Cold War was very cold; the Vietnam War was very hot. The Middle East was on fire. Other trouble-spots vied for attention by more outrageous events.

But domestic policy could not be neglected. There were racial tensions and riots. Moreover, many Johnson programs were coming due for renewal and Moynihan was a genius at using these calendared deadlines to create some domestic policy for Nixon. He conceded some of the Great Society program to the dustbins, re-badged others, and merged many to serve up a diverse and responsive domestic policy. More importantly, he couched it all in terms Nixon could recognise and accept. That is, Moynihan played to the President, whose own background was one of hard times during the Depression. For two years the magic tape held.

Nixon came to like Moynihan who addressed him as an intelligent and well-meaning man, and did not act either the sycophant or supplicant. Sometimes Moynihan addressed complicated arguments to Nixon, in a rain of memoranda, on the assumption that Nixon would read and understand. These memoranda were often short, always witty, and usually tuned to the day’s headlines. Nixon liked being treated as an intellectual equal by this star from the Harvard firmament, just as the star liked being asked to advise on all manner of things, many beyond his remit.

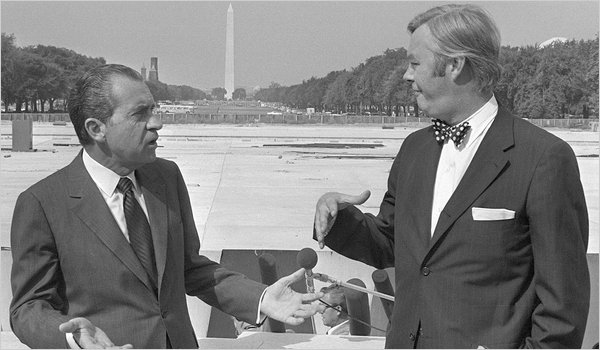

The odd couple.

The odd couple.

It did not last because when all is said and done, well, Nixon was Nixon. He was unable and unwilling to ply Congress on domestic policy. By that I mean, Nixon was not someone who would court the support of anyone, still less in a policy arena in which he had no interest. Part of his dedication to foreign policy was because it was essentially the President’s chess game. He played the lone hand. At that he excelled.

To promote any domestic policy requires a president to woo, court, explain, cajole, coax, trade favours, entertain, persuade, the chairs of sub-committees, the chairs of committees, the party elders, the lobbyists, the press, individual Senators, faction leaders formal and informal, state governors, certain Representatives, and so on and on and on. This kind of endless dance was what Lyndon Johnson did better than anyone before or since, seldom idle and never alone when he could press his case on someone.

Nixon thought this kind of politicking without end led to compromises and bad policy, or so he said, but the truth is deeper. He just could not do this person-to-person persuading even if it was scripted and controlled. We can all speculate on why. Here is my take. Because of his background of penury he was too proud to ask others for help. To do so would be admission of weakness, and the weak are reluctant to admit it. There is also in Nixon a personal shyness that is another result of his upbringing that kept him in the family. That is my pop psychologising. (Yes, I know LBJ’s background was even more penurious and he had no trouble in seeking help.)

After the first few months of his presidency Nixon sharply reduced the time he spent in cabinet meetings, and made himself less and less available for appointments with anyone. Bob Haldeman who kept Nixon’s appointment diary noted that the President said and said often ‘I want to be alone.’ Yes, I thought of Greta, too, as I am sure did Hess, but he passed it in silence.

Nixon had to be alone with those yellow legal pads to think. When Nixon was thus isolated, as he preferred, Moynihan was a few steps away and would be summoned to be a one-man sounding board, who would speak freely in the privacy of the tête-à-tête.

Like Senator William Fulbright, Moynihan had made a Faustian bargain. He joined Nixon’s band on the pledge of loyalty and that he would not speak of the Vietnam War which was the biggest and hottest ticket for the incoming president. Moynihan kept his part of the bargain.

It lasted for two years and then Moynihan returned to Harvard. He paid a price for his association with Nixon and gradually went on to a political career in the Senate, taking the seat once held by Robert Kennedy.

The price was a loss of status among his Harvard peers for his dalliance with Tricky Dick. He never quite re-entered the Harvard Square club. Indeed, his association with the Nixon White House also damned him to many anti-Vietnam War protestors. The one chance I had to hear Moynihan speak, at a political science conference, he was shouted down, quite comprehensively, by such protestors.

Stephen Hess has many other books, and I will certainly read more.

Stephen Hess.

Stephen Hess.

He is even handed, and lets the facts do most of the talking. He does, however, present most of this book in the present tense and I found that distracting, and I always find it annoying after I have been distracted.

‘Attack on the Block’ (2011)

This time the aliens try South London instead of East London, and find the locals even tougher!

What’s to like?

The gradually revealed social order amid the outward chaos of the streets, alleys, trash, and detritus of squalid urban life. The additional revelation that for most of the boys in the gang, there is a home to go to but the streets are more exciting.

The mix of races and ages. Mugging passers-by is acceptable to the code but not dealing drugs to brothers.

The foul mouthed swearing is for the streets, not when safe indoors among friends. The swearing and cursing is part of the role of the street-tough.

The implicit social criticism. First the bullies and thugs, then the police, then the drugs, then the guns, all sent to destroy the black migrants of south London.

Then come the aliens. No point in calling the police because they will blame everything on the street toughs and lock them up, leaving the aliens to destroy everyone else. When confronted with the pistol-totting drug lord, the police prefer to arrest the street boys. So much easier. No, the boys from the Block have to look after their own, so they arm up and take on the aliens.

The dope growing nerd, Nick Frost, and his nephew prove to be surprising helpful in the denouement. Some basic sciences goes a long way in this script.

When the newly-moved in nurse tries to explain to the police, who arrive in the end after the street toughs have destroyed the aliens, that the boys saved her and everyone else, the police conclude she has been traumatised by assault, threats, and perhaps rape, Stockholm Syndrome, one officer mutters, while arresting the boys.

The leader of the gang is, by the way, Moses (who led his people to the promised land).

‘Cockneys vs Zombies’ (2012)

From SBS-2 a foul-mouthed slaughter-fest featuring the geriatrics at a nursing home who take on THE ZOMBIES.

I gave it a three and a half snorts rating (four is tops) as I guffawed my way through it.

The nursing home is threatened by a new residential development for the Yuppies who have discovered how handy and cheap East London is. Two grandsons of one of the geriatrics swing into action to come up with the dosh to help out. Their solution is to rob a bank. They assemble a team. This is no A-Team, and includes a klutz, a psycho, an absent minded type, and a cousin who does have some nous. While the lads are busy robbing the bank, the zombies rise and demolish most of the East End.

When the team emerges from the bank, all is devastation. ‘Wh ‘append?, they ask? They are all pretty clueless. But the zombies soon make themselves known. Yes, the have a lot of money now, but who cares! Off they go to save granddad, sure that he will have survived the onslaught, taking along a couple of superfluous hostages who now do not want to be let loose.

What to do? Stay on mission and rescue Granddad.

It is a wild ride and perhaps not best viewed around meal time.

The nursing home includes many familiar faces from Brit cop shows hamming it up, among them Richard Briers who tapes an Uzi to his Zimmer frame, Honor Blackman who knows how to handle a gun, Alan Ford who for years played characters on ‘The Bill’ and similar programs listed in the credits as First Thug, Second Villain, Dudley ‘Tinker’ Sutton whose wheel chair becomes a tank of sorts, and Tony Selby who uses his wooden leg to beat one zombie into pulp.

These seniors have survived Dunkirk, the Blitz, Hitler and World War II, cancer, fifteen years of rationing, the Beatles, divorce, porridge (that is jail time), bell-bottomed trousers, colonial wars, Thatcher, and other catastrophes, a few zombies will not lay them low.

The discerning viewer detects a certain satire here. The Zombies taking over East London surely represent those Yuppies who are driving out the respectable and toiling masses. But then the working class is not spared either, shown to be idle and criminal in the McGuire family.

That it rates a measly 5.9/10 from 14,386 votes on the Internet Movies DataBase confirms a lot about the people to do those ratings, none of it good. There are sixty-eight reviews and I do not recommend reading any of them but I do recommend watching it, though I fear some knowledge of Brit cops shows, personnel, and conventions, will add some seasoning denied those without this background knowledge.

That old tyrant, distance.

One of the sacred text is Australian history is Geoffrey Blainey’s ‘The Tyranny of Distance’ (1966), which made his name and ever after he pontificated on anything and everything until no one (starting with me) listened to him any more. I read it 1974 and not since. The thesis of the book, as I remember, was simple. The great distance of Australia’s English settlements from England made the Europeans in Australia both self-reliant and hostile to, though dependent on, the distant authority because it was unreliable.

The term ‘tyranny of distance’ pops up now and again in the popular media as it did today in a piece on the business pages of Rupert Murdoch’s organ, ‘The Australian.’ There Bernard Salt (‘The Dallas Line,’ 4 February) told readers that Sydney (which is Australia) is more than a plane ride (with current technology) from much of the world. OK, that is certainly true. No airline flies direct, non-stop from Sydney to London or from Sydney to New York City. This, he contends is detrimental to Australia because that is where the money of the world is. OK, that is also true, but what is the detrimental part? That was not articulated, instead the mantra distance is tyranny was cited. One pictures travellers lugging bags of dosh around inside that London-New York nexus unable to change planes, such is the size of dosh bags, in Los Angeles or Dubai.

The news is, and perhaps this is news to some, that money moves around the world in click of the keyboard as the cascade of financial crises around the world has repeatedly shown. Distance does not insulate any country from such financial calamity. That fact is ritually reiterated on the business page of the organ of Murdoch several times a week. Salt describes himself as a futurist on his web site. Think about that.

By the way, the other side of the tyranny of distance that Blainey mentioned was that in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries distance did insulate Australia from some of the more dopey and ephemeral fads that came and went elsewhere before they made the trip to Australia. No Edsel or Apple Newton made it to these shores. Not from all such fads but some. It also insulated Australian from some infectious disease epidemics. No more. Bad ideas are replicated here within twenty-four hours.

The distance was measured in travel time as much as miles. Blainey wrote about Australia as remote but of course it was not remote to its aborigine in habitants, nor was it far from the South East Asians who regularly visited the northern shores.

The colonial master in the formative period of Australia’s European history was a long way away in both space and time. It might take, at best, six months to travel from Sydney to London. Moreover, it was unsure. Ships turned back; some were even less fortunate. Others jettisoned cargo, like correspondence, in heavy seas and so the letter went unanswered. When word did come through from London it was so late as to be laughable, fertilising the attitude that authority was remote, anonymous, and stupid.

The result was the Australian political culture of the 1970s, one that entwined a dependence on government for nearly everything from the marketing of eggs to trimming of hedges, while disparaging government and all who worked for it as cretins. Australians wore this anti-authoritarianism with pride, automatically against the government even while waiting for the next handout from it. Rather like a teenage boy rebelling against his parents while pocketing the weekly allowance and storming off to a room provided by the detested parents.

For Australia the first breach in the tyranny of distance was the Boeing long distance jets that supplanted ships for the travel of mere mortals in the 1970s. There followed a generation later the digital world which has shaken many of the most solid institutions like newspapers themselves.

Why read Murdoch’s organ when I can click up BBC News, Le Monde, or Deustche Welle? (My personal answer, since I have been asked this, is the local news that will never make it to these outlets, and the reviews, cultural, and entertainment information. And the nonsense that ever fewer, ever more desperate journalist write, which provides unintended – always the best kind – entertainment. And reading them on paper is still more convenient that on screen.)

When the fad for small government was born on the winds of Proposition 13 (that was referendum for the taxpayers’ revolt in California) in 1978, the spores circled the globe and arrived in Australia rather like the cloud of radiation in Neville Shute’s ‘On the Beach,’ Australians happily shrank government. The one example I witnessed firsthand was the higher education division in the Federal Department of Education which shrank from 400 to 40 to 14, probably 4 now. Each successive government wins office on a pledge to cut government spending, and cut they do. This is now a forty year race to eviscerate government.

Of course a lot of things go wrong as the cuts were made, but as one prime minister said, ‘Not our fault.’ End of that story.

Strangely enough though government has vacated many realms from airlines to docks, the tax bill has not decreased but the automatic anti-authority posturing has decreased so some good has come from it. Though poseurs quickly find other posture to affect, it is true to say.

The French Social Model

We do not hear much about the French Social Model (FSM) these days, now do we? For those who tuned in late or tuned out early, in the first decade of the 2000s the French Social Model was often invoked in hushed and respectful tones, even here in the far antipodes.

When students proposed to do theses on the French Social Model, that was the first I had heard of it. They were getting the message elsewhere. Then at conferences there were sessions that included the FSM. When I returned from a conference in Paris at the OECD, the Master of the Universe to whom I then reported asked about the manifestations of the FSM, in the expectation that they were there to see, I guess, in the streets.

Of course the same people who humbled themselves before this mirage of Gallic sagacity were unsparing critics of the Anglo societies in which they lived. Liberalism was a hoax and democracy a sham in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Of course, few pay into the system.

I had to report to my boss that there were no signs of utopia in Paris between the hotel room and La Défense where the OECD talkfest occurred. (The area is called La Défense because the Prussian Army stopped at that point in 1870, preferring to let the French in Paris kill each other in the Commune. In French mythology the Prussians were fought to standstill. There are people who think they stopped the Germans in 1940, too, at the Pyrenees.)

Then in 2006 there were riots in the streets in the Arab and African quarters of Paris and other French cities. Gulp! It went on and on. There is plenty of video on You Tube for those who need a refresher. The complaints and demands were many.

What French Social Model? A repressive police apparatus, the routine deportation of anyone who complained too conspicuously, withdrawal of the license to publish in some cases. Fifty per cent unemployment because no European French would hire a dark skinned person. Automatic failure in school for anyone name Ahmed. Denial of family reunion immigration. Closure of hospitals in the third world parts of Paris. The list goes on.

It had been going on for decades and was as effective in deluding intellectuals seeking an illusion to go with the fumé blanc and brie as the Soviet Union had been in the 1930s with vodka and black bread. Neither the levels nor means of repression in the two cases are comparable. What is comparable is the readiness of some intellectuals to be deluded by a convenient illusion.

The worship of the FSM has gone quiet of late. Not even the election of the Socialist President François Hollande quite revived it. This accountant from the country has seemed to be in over his head as did his predecessor (who is now lining up to be his successor). The cleanskin Socialist Party has stumbled from one crisis to another, several if its own making.

President Hollande

President Hollande

My personal favourite was the Socialist finance minister who pushed for draconian penalties for tax avoidance for all sorts of patriotic and humanitarian reasons. He was undone when his own personal tax avoidance became public knowledge. First he denied the monies existed. Then that the monies were significant. Then that the monies were really his (reaching for his wife as a shield). That it was an oversight. Then…. Then he resigned. Oh, and there was that other financial wizard caught with pants down in New York. Ah, the moral leadership of Socialism. That event thrust Hollande into the leadership.

The point is, for those about to jump to a conclusion, not that the Socialists are any worse than others but that they are no different.

Then in response to terrorists attacks, the Socialist President has declared an open-ended state of emergency. Wow! Imagine if President George W. Bush had done that in 2001! He would have been verbally crucified by the talking-head industry around the world and certainly here in Australia where throwing stones at far-away others is a career. The French attacks were bad, to be sure, but not on the scale of 9/11, but the reaction has been far greater and quicker. Not much of it makes the Australian news in preference to car accidents on the Pacific Highway.

Viewers of TF2 news on SBS see daily reports of continuing police raids, and shoot outs. Dare I call this the Real French Social Model? One suspects that the police have had a long list of villains and now they have the justification to strike at them.

The French Social Model has some adjuncts. The French budget has not be balanced since Valery Giscard d’Estang was president (1974-1981). The debts just keeps on rolling.

One of the biggest drains on the budget is the military establishment which accounts for about 40% of it, which is then used for frequent armed interventions in African, including the Arab countries in North Africa. Those admirers of the French Social Model never pause for long on this prolonged neo-colonialism but one images the outrage if the United States did what the French do. Such are double standards.

French African Model

French African Model

At any one time France has military units deployed in twenty or more places in Africa. Colonialism or the Gallic Enlightenment?

Freeman Dyson, ‘Disturbing the Universe’ (1979).

Dyson is sometimes said to be the greatest physicist never to win a Nobel Prize, settling instead with having a space craft named for him in ‘Star Trek.’ The book is autobiographical but not an autobiography. Huh?

The essays set forth something of his life and career as a scientist from his first absorption in and simple adsorption of mathematics, to statistical analysis during World War II in Bomber Command, to theoretical work in the Cold War… That is autobiographical part. However it does not offer much of the private man, though we do find out some of his personal life there is no interior, and it is shorn of any reflections on the might-have-beens in his life. The ruminations, and there are a few, are about science and scientists and those they effect or effect them.

He, by the way, was perhaps among the one million Allied soldiers estimated to be killed in the conquest of Japan, who was saved by the atomic bombs. He had been ordered to Okinawa with a contingent of RAF Bomber Command to join the aerial campaign against Japan in anticipation of a sea landing in November 1946. The Allied planners had assumed one million (1,000,000) Allied causalities to subdue the islands of Japan, based largely not the resistance on Iwo Jima and then Okinawa. He read the news of the first atomic bomb en route to the boat train for the Orient. His orders were altered, and he was demobilised. (The planners also assumed ten times that many Japanese deaths in the conflict and untold numbers later in the devastation of the entire country that would be necessary to subdue it.) The planners also assumed nearly all of these Allied casualties would be Americans, since the other Allies were depleted by the war in Europe and that the Soviet Union would play the waiting game, if for no other reason than in retaliation for the tardy opening of the second front in Europe in 1944. Among the many contingency plans for this operation was, after Japan had been bombed flat, to convert air force personnel to infantry and send them into the charnel house. One such flyboy being converted to infantry in 1945 was my father.

‘The Children’s Crusade’ is the chapter about his RAF experiences. It is an absolutely outstanding account of bureaucratic pathology. I used it a number of times in teaching. The more lies told, the more innocents murdered, the more lives thrown away, the greater the prestige of Bomber Command, the more knighthoods distributed, the larger the budget to continue the mayhem, the less rational analysis occurred. Nothing unique about it, but he lays it all out in a way that is all too familiar.

He started a PhD and sent a year at Cornell University with Hans Bethe, who sent him on to the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton New Jersey to work with J. Robert Oppenheimer. Many of the Los Alamos scientists, apart from Oppenheimer, had been hired by Cornell. (Chicago got the rest.) Entering their company was exhilarating and frightening to the young Dyson. They had won the Pacific War with their brains, it seemed to him, and now he was one of them, well, not really, but he was among them.

He found Cornell and later the Institute very different from Cambridge where he started the PhD research earlier. First, there was plenty of everything from butter to test tubes and clean, crisp white paper. To a theorist like Dyson, who quickly proved himself so inept at experiments as to be a danger to anyone else working nearby, the clean, crisp, empty white paper was a thrill. (Reminded me of paper elsewhere.) Second, he found the informality of first names, all lining up together for lunch, and sitting at one table different from both the RAF Bomber Command, of course, but also from the class, status, and hierarchy consciousness of Cambridge high tables.

There was another distinguishing feature that stayed with him. The anguish of the atomic scientists at having unleashed the atom. Most days at lunch or coffee someone would talk about it as a moral question, as moral guilt, as a genie that would not go back into the lamp, as the last consuming sin of hubris.

It is in this context that Dyson interprets Fredrick Teller’s fatal testimony against Oppenheimer, and it makes sense in this telling. Oppenheimer was so distraught, feeling ashamed and guilty, stunned, confused by the enormity of nuclear weapons that he had become unstable, volatile, sleepless, haunted, and so was not fit for duty. Teller was trying to make a specific and limited criticism of Oppenheimer’s fitness for the job as director of the Atomic Energy Commission, but in the hysteria of the time and place it got blown out of proportion and Teller never lived down this betrayal of his mentor, doing himself as much damage as he did Oppenheimer. Of course, Teller might well have realised that once he took a public side, it would spin out of his control. Too bad the principals of Wikileaks did not learn from such an example. Once it is out, it is out of control. This is one of many examples in the book of the disservice the media does to reason and rationality with its remorseless, cheap sensationalism.

Toward the middle of the book is the story of Matthew Meselson, a biologist, who won a single-handed victory in the Nixon Administration. Armed with reason and evidence he convinced the National Security Council, which in turn convinced President Nixon, to end military research into chemical and biological weapons: One man with an idea, per John Stuart Mill. Moreover, having renounced CBW (chemical and biological warfare) the Nixon administration convinced the Soviet government to do the same, completely in contradiction to the conventional wisdom. This is a marvellous story which was swamped too soon by the tale of Watergate. In order to slip it past domestic opposition, Nixon played it all so low key many involved did not realise it was done, least of all the sensation-seeking media. No great rhetoric but an achievement for the ages. Dyson was one of the scribes doing the technical work on the reports and proposals that went into this effort.

Nixon also deserves credit for listening to the arguments of Daniel P. Moynihan about cities as per Stephen Hess, ‘The President and the Professor’ (2014) but again, to out manoeuvre opponents on the right, Nixon did so with no fanfare to attract the the attention of the jaded hacks.

Dyson like many of his scientific colleagues drew strength from poetry and music. Indeed he often tried to understand what he was doing by finding poems that expressed it. The same with music. He emerges from this book as a modest and direct individual with a great deal of intellect and capacity for meeting challenges, solving problems, indeed, but not only technical ones.

Freeman Dyson.

Freeman Dyson.

Lee Hansen first enticed me to read this book, and I used the chapter about Dyson’s experiences in bomber Command many times in teaching to demonstrate the pathologies of large organisations. I lent it to a friend and when he returned it, I opened it and started to read it again. I had thought of it last year when we saw ‘Particle Theory’ about the God-particle, and I noticed the enormous spectacles on the nose of an owlish man in the audience; it was Dyson.

While in the States Dyson did what so many exchange students have done there, including Jacques Chirac, and criss-crossed the country by bus. Dyson chose his destinations according to his finances and the physicists he might meet at the destinations, either by attending lectures or knocking on the office door, things he would never have done in England.