What is reality? What is not? What is the difference? Does it matter?

This is a novel from Finland, read in anticipation of a brief visit there later in 2016. It is charmingly enigmatic and low-key, rather reminding this reader of Finnish movies in those respects.

It is episodic, written in what might be diary entries of a young woman who, after graduating from university, goes to work in the editorial office of a publication called ‘The New Anomalist’ which is a one-man publication that prints only the weird and wondrous; two-headed sheep always get a good run.

Our nameless heroine tries to be nice to the oddballs and weirdos who contribute to the magazine, want to contribute to the magazine, or subscribe to it. Gradually, with constant exposure, they seem less weird and odd to her, and her own normal life seems illusory. Part of the explanation, for the literal minded, is in the title, but I took that mostly to be a metaphor for erosion of her own grasp on reality. Datura is an hallucinogenic.

Leena Krohon.

Leena Krohon.

While it is set in Helsinki that hardly matters. Mostly the encounters and rumination occur in the dreary one basement office of the magazine which could be anywhere. Ergo, no travelogue.

Author: Michael W Jackson

John Stuart Mill, ‘Auguste Comte and Positivism’ (186?)

I wanted to read this little book (unpaginated) because my efforts—thrice over the years—to read Auguste Comte’s (1798–1857) ‘Système de politique positive’ (six volumes, 1851-1854) failed. While Comte was the centre of much intellectual ferment he has not attracted much attention so I have not come across another exposition. I also thought Mill a good expositor, most of the time.

Comte was private secretary to Henri de Saint-Simon, that father of French utopian socialism, in the tag that Karl Marx hung on him never to be shed, who was himself a relative of the diarist Le Duc de St.-Simon of the Sun King’s Court. Moreover, any history of sociology will accord Comte pride of place alongside such giants as George Simmel and Émile Durkheim. George Eliot, the novelist, mentions him in some of her novels in a very favourable way. His name comes up now and again. When I was in Montpelier for a conference I saw a plaque on a school where he was educated. Time to scratch this itch, if only a little.

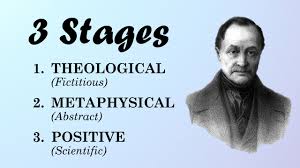

The ‘Système de politique positive’ offered a philosophy of history that explains humanity’s social evolution through the stages of theological and metaphysical, culminating in the age dawning in 1851, the age of Positivism. These stages take different forms in mathematics, science, the arts, industry and so on, and Comte described them in great detail.

Auguste Comte with the three stages of social evolution.

Auguste Comte with the three stages of social evolution.

In this context ‘positivism’ means a lot more than positive. It means saying only what is demonstrable. He is a materialist after Karl Marx’s own heart. Facts shape ideas, and not vice versa. One of many consequences of this foundation is that reason serves feeling but does not govern it. Herbert Spencer took much of this epistemology on board, and, like it or not, set it forth much more succinctly and clearly than did Comte.

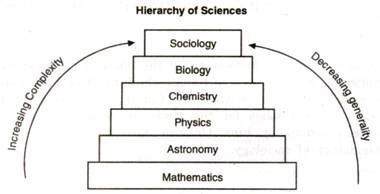

In Comte’s interpretation mathematics is THE science, the foundation of all else, because it is the simplest and sociology is the last science because it is the most complicated. The Wikipedia entry has a potted account that shows signs of the editorial wars for which it is infamous.

Social evolution, per Comte, thanks to Positivism, will lead to a unanimity on all matters, starting with mathematics, by sticking only to the demonstrable. The result is utopia, though Comte does not use the word. Once this unanimity is achieved, then a corporation of philosophers, regarded with reverence, but excluded from political power or material riches, with a modest support from the state, will direct the on-going education (and life) of each individual and the society as a whole. While they have no authority, a sanction from this college of philosopher has a crushing social and moral force. They superintend both the public life and the private life of each and all. They are a panel of very Big Brothers.

Comte’s hierarchy of the sciences.

Comte’s hierarchy of the sciences.

There co-exists a temporal government which is comprised of an aristocracy of capitalists, led by bankers, seconded by merchants, then manufacturers, and finally agriculturalists. In each case the noun refers to the owners not the workers in these domains. There is nary a word about a role or voice for the multitude who do not own banks, grands magazines, factories, or farms. However, there is completely free discussion. The elephantine six volumes brings forth this rather simple-minded pastiche on Plato’s philosopher-kings. Absent is any mentioned of women, contra Plato. By the way, St. Simon was a banker.

Comte could see no reason why inferiors should elect the superiors who will rule them. Public officials should be responsible for training and selecting their own successors subject only to the approbation of their own superiors. This is a man who believed in hierarchies. A citizen must have a settled career by thirty-five, and after that may not change. This is a man who believed in order at any price. No one may pursue occupations that are not useful. So much for basic research. He was specific about stopping useless research into magnetism, archeology, astronomy, and more. Imagine how popular he would be today with budget cutters. The corporation of philosophers will decide what is useful. End. This corporation will also decide which one hundred, yes, one hundred books will survive and the rest will be burned! One hundred is enough, the rest mere distractions.

Comte regarded rich capitalists as a public functionaries and stipulated that they must act accordingly. Talk about a dreamer. What socialists would achieve by law, Comte hoped to achieve by education and suasion, capped with the peer pressure of public opinion.

Such a result may cause a reader to doubt that it is worth the effort to study the volumes that lead to it in order to understand how Comte arrived at such banalities. So says Mill in one of his drôle asides.

The second half of this unpaginated book is another essay on Comte’s later works which were just as ponderous. Comte took the time to explain his own genius. He never read anything but reflected within himself. Echo Rousseau. The result is an autodidact with a great conviction. He was mentally unstable as a youth, voluntarily spending time in an asylum, and later attempting suicide. In middle age, like Mill, he found the love of his life and told the world. This comparison to Mill’s austere passion for Harriet Taylor might have warmed Mill to Comte.

In the latter works Comte goes even further, devising a social religion that leaves behind the metaphysical and theological claptrap of organised religion and preaches this doctrine and this doctrine alone: live for others. In arriving at this creed, he coined the word ‘altruism.’

‘Live for others’ is literal. One should only do what benefits others. This is not Jesus’s admonition to love neighbours as oneself, but rather not to love oneself at all but only to love neighbours.

Comte was systematic as indicated by the title of the work cited above, and he carried this creed through in everything, from diet (eat only enough to be able to serve others), to dress (simple and utilitarian to serve others), and so on. Everything becomes a moral question settled by this one doctrine. In short, he required that each of us live as a saint practicing self-abnegation in our every act. Followers? He had none. Nor is there any reason to belief he lived as he advocated, rather like most pundits today, he preferred preaching to practicing.

His lady-love died within a year of their conjunction, consequently Comte, like others so bereaved, was attracted to spiritualism. He included guardian angels in his civil religion, and it seemed to be more than a metaphor.

He also proposed an elaborate civil religion with a Pontiff Positive, which would preach the doctrines he proposed. He supported Napoleon III’s coup d’état because it did away with the charade of elective democracy (which Comte always dismissed as the English disease), and predicted that in a few years Napoleon would turn over government to three wise men. Guess who would be the first to be chosen. That day came and went without the magi.

Comte was not a man who knew when to quit. He proposed to give each day of the year a name, to make the week ten-days along, to rename the planets, to change spelling and orthography, spending pages and pages on the evils of diphthongs. (Look it up!)

The more one reads of Aristotle, the more clear is his towering genius. Ditto many others. In the case of Comte, the more one reads, the less one wants to read any more.

Recently I saw on Télévision Française 2’s news broadcast aired by SBS each morning, which I watch for my daily French lesson, the induction of a scholar into the immortals of the Collège de France, the robes, the ritual procession, the pecking order, the props were all very Masonic to this vulgarian. (There were no more than three women; the immortals number one hundred and no one may resign, ergo someone has to die for a new member to be selected.) These individuals are the sort Comte had in mind for rule.

Collège de France logo. I could not find any imagines of a ceremony such as I saw on the news.

Collège de France logo. I could not find any imagines of a ceremony such as I saw on the news.

Of course, while they retain the trappings of veneration, in fact the broadcast had the air of curiosity more than reverence.

This book is not Mill at his best as an exposition. But it soothed my it itch for Comte. Each sentence is a thicket of dependent clauses, noun phases so long that a GPS is needed to find the predicate, encyclopaedic asides, orphaned relative pronouns, that it taxed this reader. In the essays, for which he was paid by the word, Mill is prolix; in his books which he paid for publishing by the word, he is terse. Go figure. His father had Scots ancestry.

Sharyn McCrumb, ‘The Windsor Knot’ (1990)

This title is a krimi set in contemporary rural Georgia in the borderlands with South Carolina and Florida in a small town whose chief denizens are the Chandler family. Belay those stereotypes!

The Chandler sons are an actor of great ambition and little talent, and a physicist who is proud member of the nerd fraternity. Captain Grandfather spend forty years at sea in the navy. Aunt Amanda, had she been available, would surely have repulsed General Sherman at Atlanta with her wit, skill, forceful personality, and the endless supply of contacts in the right places.

Returning to this fold is niece Elizabeth MacPherson, a forensic anthropologist, to be married in the ancestral home. Her unreconstructed hippie parents continue to smoke dope in Hawaii, trusting all arrangements to the Chandlers in residence.

Her beau is a Scots marine biologist; they pass the time with discussions of decomposition rates of flesh.

The plot thickens when local Emmett Martin dies…for a second time. I will say no more to spoil the plot. Suffice it to say it is clever, rIght down to the Biblical nomenclature.

McCrumb is a dab hand at delineating a cast of characters as individuals from all those named above to the several sheriffs and deputies, the scientific colleagues of each of the principals, and the townspeople, including the whole-earth tree-hugging tofu-eating caterers for the wedding whom Amanda suborns into serving flesh. Even the Queen of England and a princess make an appearance!

Sharyn McCrumb

Sharyn McCrumb

This is the second in the series centring on Elizabeth MacPherson, and I will lay in the first. However not sure about continuing thereafter. With neither zombies nor bimbos, it does not reach the heights of the other books of hers I have read. Being a one-woman industry she also has several other lines of fiction.

Agatha Christie said the secret to finishing was to start. McCrumb got the message.

Alan Sillitoe, ‘The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner’ (1959)

This a collection of short stories that opens with the title story of Smith deliberately losing a race in order, as he sees it, to defy the authorities. Winning would have benefited him, but it would also have benefited the warden and jailers of the Borstal where he is held, and rather than do that he loses, and does so in a way that is obvious to viewers.

It told from his point of view and is hypnotic at points, especially during the fateful run. Once a reader starts, it draws one in.

Most of the stores have a common theme in loneliness. ‘Uncle Ernest’ is a touching story of a very lonely old man trying to befriend some innocent school girls, which is misunderstand by on-lookers. but who knows, maybe in time, Ernest might …. There is just enough ambiguity to make a reader wonder. No sledge hammer morals here.

‘Mr Raynor the School Teacher’ is another person trapped in his own, very small world, dealing with obstreperous boys, some of whom will find their way to the Borstal nearby. Meanwhile, he daydreams, but never dares speak his mind.

‘The Fishing Boat Picture’ is about love and sacrifice, but all clouded by the inability and unwillingness to communicate. Maybe the characters cannot say what they feel because they just do not know how to do so or they do not quite know what they do feel.

Alan Sillitoe at the time the book was published.

Alan Sillitoe at the time the book was published.

There are four other stories, suffice it to say. I enjoyed reading each of them. Though the petulance does wear thin. Sillitoe was one of the ‘Angry Young Men’ of British letters who found the post-war Welfare State inadequate.

We forget just how long it took Britain to recover from World War II, for example, in meat rationing, petrol scarcity, in employment. It did not enjoy the years of growth and plenty that the United States had during the Eisenhower years. One of the reason the decade of the Swinging Sixties was so liberating was because finally it heralded the end of this wartime privations, that had long ended in other English-speaking countries.

The Wikipedia entry on the story is convoluted and one-eyed, as well as pompous. But it has probably benefited editing twice since I looked at it ten minutes ago.

Tom Courteny in a still photograph from the 1962 film based closely on the titular story. I started to type that Courteny was born to play Smith, but then I thought the same about his performance as Ivan in ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970).’

Tom Courteny in a still photograph from the 1962 film based closely on the titular story. I started to type that Courteny was born to play Smith, but then I thought the same about his performance as Ivan in ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970).’

Another book that turned up during our move.

The Liberal Expectancy

One of the silent assumption of western societies for the last two generations is now undergoing a severe test. Like most assumed truths, it is seldom stated, and certainly not by the talking heads who can never shut up long enough to think.

What assumption is that?

That life in western societies would erode, reduce, and in time eliminate ethnic, tribal, and religious identities and with the passing of these differences, then we can all live together in peace regardless of race, nationality, language. The old conflicts, animosities, hatreds would wash out in the tolerant bath of multiculturalism.

Societies governed by the rationality of the Enlightenment would create the conditions of life in which these superstitions of the past, ethnicity, tribe, and religion, would fall away.

On such assumptions migration was an opportunity not a problem. While migrants will bring in the baggage their ethnic and religious identities with corollary divisions, these will be subdued and written over by their new lives in Western societies, leaving behind their energy, spirit, and creativity.

While the word ‘liberal’ has been as verboten in academic circles as it is in Republican ones, this was one of the core of liberalism. (Strange isn’t it that the self-styled Left of the Academy and the self-styled right of the Republican Party, now represented by Donald Trump, are as one in reviling liberals.)

Another object of revulsion in academic circles for years has been sociologist Daniel P. Moynihan, whose chief sins were calling attention to the implication of social structure and working for Richard Nixon. Just the kind of sell-out to be expected of a liberal! So harrumphed many know-it-alls of my acquaintance. That in both cases Moynihan promoted and acted as a mid-wife to many social programs that benefited millions is irrelevant to the classroom stone-throwers.

Moynihan tried to disabuse us of this liberal expectation that ethnic and religious identities were but flimsy substitutes for the good life and once the good (material) life was in sight, they would retreat into scrapbooks of the past. He argued (‘Beyond the Melting Pot’ [1974], pp 33ff) and he had plenty of evidence at his command in so doing that ethnic identity and religious commitment were essential to the identity of (many, if not most) people and would endure come what may. These identities could withstand the oppression of police states in Eastern Europe, he said, and they could certainly withstand the seductions of Western materialism. A refrigerator would never replace a god. I once saw him more or less drowned out and shouted down at a political science conference advancing this argument. Edifying, not!

According to this liberal expectancy religion and ethnicity would evaporate in the melting pot of migrant societies. No longer would it be possible to mobilise people by appeals to ethnicity, tribe, or religion. Indeed, one of the silent goals of liberal society was to liberate us from ourselves (our identities as Walloon, Jew, Inuit, Shia, Tatar, Catholic), stripping away these overgrowths and leaving behind the deracinated cosmopolitan.

Daniel Pat(rick) Moynihan

Daniel Pat(rick) Moynihan

The resurgence of ethnic nationalism, religion, and tribe in the skeleton of the Soviet Union would come as no surprise to Moynihan, though it did surprise a great many social scientists who are now less conspicuous at conferences. Nor would he be surprised by the continuing response to the appeals of religion everywhere in the world, but most social scientists are baffled by it.

George Will, ‘A Nice Little Place on the North Side’ (2014)

William Butler Yeats wrote that ‘life is a long preparation for something that never happens.’ No, he was not thinking of the Chicago Cubs in a World Series, but it fits.

I omitted the subtitle: ‘History, Triumph, Mostly Defeat, and Incurable Hope at Wrigley Field.’

George Will has long been an expositor of baseball, well before Ken Burns discovered it. This book is an ode, spiced with some gritty reality, to Wrigley Field and those who have graced and disgraced it from zealous fans, first-ball throwing presidents, class and déclassé players, managers, and owners including the fabled P. K. Wrigley, famous for his indifference to baseball and his genius for marketing.

All of the lore is here reiterated: Babe Ruth calling the shot, Hack Wilson the perpetually hungover human fireplug, the storied Tinkers-Evers-Chance, smiling FDR throwing out the first ball, Ruth Ann Steinhagen shooting first baseman Eddie Waitkus (who had never met her before she pulled the trigger on him), Wrigley’s many innovations from Ladies’ Day to the ivy on the walls, and his decision to contribute the steel for light poles in 1941 to the war effort and the resulting, accidental, consecration of Wrigley Field as a cathedral to daytime baseball. Waitkus, by the way, was the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s novel ‘The Natural,’ ironic since Malamud had no interest in baseball, nor any knowledge of it either, as is apparent in the novel, somewhat emended by the screenwriter for the movie of the same name.

Did the Babe really call his shot? The record is far from clear, but the legend is indelible. Tinkers-Evers-Chance turned very few double plays but the journalist who said they did, created a reality that has endured despite the wizardry of sabermetrics. Will is very good at presenting a lot of facts, including statistical data, in digestible portions with spritely commentary, including the paltry number of double-plays this trio made in the year when they together ascended to myth.

Hack Wilson was certainly hungover on days when he blasted home runs. His drinking shortened his career and life dramatically. FDR and Chicago Mayor Anton Joseph (Tony) Cermak made an odd couple on opening day in 1933, and even more so a few weeks later in Miami when Cermak was murdered at FDR’s side, the speculation being that Cermak was the target of the Mafia as a warning to FDR to call off the IRS or to leave Prohibition alone, which had made them millionaires.

The end of live-ball era is much discussed, surprisingly, without much enlightenment. The rather mystical implication is that the live-ball ended with the advent of Great Depression. One catastrophe begat the other. Members of the pitching fraternity did not mourn the end of the live-ball era and celebrated the dead-ball era. I speak as a brother of this lodge.

The Olympian RBI totals Wilson and others compiled in the live-ball era endure, unlike most other records from the days of yore. Why is that? In those days most teams had but one big hitter who was preceded by yeomen who hit singles and were thus on base for the clean-up man. In those days before money-ball, pitchers threw strikes to such clean-up hitters and the RBIs followed. In subsequent years most teams have more, better hitters so there are just fewer ducks-on-the-pond when the sluggers pounds another home run. And pitchers are often instructed not to pitch to the big hitter when there are runners on base, even to the point of walking in runs. Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire hit phenomenal numbers of chemically-assisted home runs without threatening the RBI record.

Denizens of Wrigley Field have included the great and the good, the ordinary and the unknown, and the bad and the ugly. In the heyday of the aforementioned Prohibition Al Capone was a regular. Later Jack Ruby sold peanuts there before finding his way to a Dallas basement carpark a generation later. Ray Kroc had his first experiences at retail food in the concessions under the grandstand. And of course those indefatigable entrepreneurs the Bill Veecks (as in wreck, they always said) Senior and Junior.

While the leagues expanded and new stadia were built Wrigley Field, together with Fenway Park, remained testaments to the past. These new stadia seated tens of thousands, and came equipped with all mod cons, as the realtors say, from plasma television screens to beer on tap, cushioned seating, hot and cold running distractions, and more. They occupied vast tracts of land, sometimes seventy acres far out of town; the further out they went, the more parking they needed for fans to drive cars there; the more parking they needed; the further out they went. Some went so far out they no longer have a connection to any city like Foxboro in Massachusetts.

The needs of television to fill airtime and the need of the owners to sell fans more than a ticket once there, and the needs of fans to do more after driving hours to get there and back turned many such stadia into entertainment complexes. The distractions are many. One of the worst, and there are many contenders, are sound system that assault the senses, though thankfully being largely open spaces, never as excruciating as at NBA games. Being more expensive than the Apollo space program, these colossi have to multi-task, and this was integrated into their design: baseball, football, rock concerts, soccer, you-name-it, anything and everything.

The predictable result was that they do not suit any of them, least of all baseball, which is best played on Astro-dirt.

Wrigley Field stood apart from this pursuit of Baal for a generation or more, literally held together by chewing gum in more than one way. However, the balance sheet caught-up one day. Lights came. There followed a scoreboard that can be read by Apollo astronauts on the way to the moon.

Will deftly demonstrates that the fortunes of the Chicago Cubs who play (at) baseball in Wrigley Field are less important to fans than the price of beer. That price predicts attendance better than the team’s winning percentage (which the cognoscenti know seldom tops .500). The Cubs team has long been the lesser interest both to the ownership, the management, and the fans than the beer.

Will discreetly leaves the players out of this list those indifferent to the game itself. Though some of them did not evince much interest in the game while playing at it what with two errors by the same outfielder on one play in several games, six walks and a balk by a pitcher in one inning without a single out, ground balls lost in the sun, outfielders charging balls hit over their heads, one batter called out on strikes without a swing of the bat a record number of consecutive times, infielders unaware of the location of the ground when it came to ground balls, players traded…for themselves with a cash refund. All of which makes the achievements of some individuals all the more remarkable, like Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks, Bill ‘Sweet’ William(s), Ferguson Jenkins, Ryne Sandberg, Kerry Wood, and a few others.

The book ends with a coda from that poet of baseball Bart Giamatti, he who banned one of its greatest players (for not playing by the rules), who chided us to remember that it is just a game and that is why it is so transcendent, for two hours outside the river of time.

As the story draws to a close the team has changed hands several times and the unforgiving business of major sports prevails, though others have learned some of the lessons of Wrigleyville, as the neighbourhood calls itself, and some new stadia are more like Wrigley Field these days than Chavez Ravine (that is a memory test).

George Will

George Will

When I ordered the book I did so in the recollection that George Will is a wordsmith of excellence, and that assumption was amply vindicated by the light touch, the glib segues, the pertinent metaphors, and the economical allusions. Altogether a perfect game of a book. I read it in one sitting. Gulping it down.

Andrew Brown, ‘Fishing in Utopia: Sweden and the Future that Disappeared’ (2009)

This book came to mind when I read Michael Booth’s ‘The Almost Nearly Perfect People’ (2014) survey of Northern Europe. Booth mentions Brown’s book, too, in a rather left-handed way. Relying on my cataloguing system, I found this book on the shelf at the Ack-Comedy and had a look.

As when I read it first in 2009, I find it to be an understated book that neither condemns nor praises Sweden, the Swedish way, the Swedish model, and, accordingly, it does not satisfy the ideologues. It is low key in every way. It is more a personal memoir than an assessment of Sweden.

Brown lived in Sweden as a boy with diplomat parents, and later as a married man, and worked for a living in a sawmill. His experience of Sweden is far different from a travel writer who passes through for a few weeks of interviews in hotels and restaurants, and guided tours of the country side. His voice is muted and his comments are largely derived from direct, personal experience. Little is black or white, little is so clearcut to satisfy an ideologue. More importantly, his perspective is working class and from the hinterland, not urban middle class.

To judge from krimis Sweden is worse than Midsomer, every street, every town is replete with pedophiles, Neo-Nazis, Sven the Rippers, people smugglers, drug barons that put Latin Americans to shame, bankers who gave the Lehman Brothers lessons, and corporate villains to dwarf Enron, and worse. Anyone with a new car, a bank account in the black, a country cottage, a fine coat, got it by foul means. This compound of envy of the rich and imputation of evil to others is to be found in some other Nordic krimis, too, e.g., the Dane Jussi Adler-Olsen becomes poetic in his lyrical hatred of those he regards as rich. There is no depravity of which they are incapable. I fully expected to find his villains eating their own children, so I stopped reading his diatribes in malice.

But to return to Sweden, of course the pathfinders in this social criticism were Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. By the tenth volume in their Martin Beck series, the villains were cannibals. The first books in the series were police procedurals but along the way the authors ascended a soapbox and every page contained some sort of denunciation, not just of the evil rich, but the Swedish society that bore them. They attacked not just the filthy rich but the Social Democratic scrum who ran the place strictly for the benefit of the rich.

Talk about parochial! The authors lived in a decent society that had gone from subsistence farming to industrial surplus in the three generations, and they hated it for what it was not, namely, a communist Eden. It is rather like those self-righteous leftists in the 1960s who denounced Western liberalism as evil incarnate, while lining up to shake hands with Pol Pot. They do not know evil, that is for sure. Wake up! Look around. Try a few weeks in the third world. These very same types would spent hours defending Robert Mugabe, Muammar Gaddafi, or Fidel Castro, while condemning parliamentary democracy as a sham.

In contrast, Brown offers an everyday account of life and work. struggling to learn Swedish on the job in the mill. He finds much different from the England he left. As he notes many times, in Sweden there was a palpable sense of unity among the people he worked with which was aimed at getting things done. Ergo, the work in the factory was hard and everyone went at it with determination, including the owner. He contrasted this with his experience of working in a factory in England where the union made sure productivity was just enough to keep the wheels turning and no more. In Sweden everyone, including the union, wanted to get as much done as possible, whereas in England everyone, led by the union, want to do the least.

The unforgiving climate, the brutal history of the region with Germany on one side and Russia the other, and the recent past of grinding rural poverty combined, he speculated, to teach Swedes that the world does not owe them a living. They will have to earn it day by day. Brown met variations on this attitude in different guises, including church attendance. He found that religion, not necessary denoted by church attendance, seemed important to Swedes in the countryside where he lived. It was a sign of the larger whole beyond the individual.

That sense of a larger whole was comforting at times but stifling at others when he encountered a herd mentality such that no one dared to be different. Individual self-expression was actively disvalued in this milieu.

He is an outsider and is constantly aware of that and as constantly reminded of it by others. Swedes do not worry about what it means to be Swedish because they know it in their blood. They do not talk about it, they just live it. Brown wonders how this silent unity will wear with increasing immigration, made necessary by declining birthrates. The expectation to conform in Sweden is much greater than in England but there are almost no explicit clues about how to do it; he depended on his wife to cue his behaviour, say when checking out books at the library, cashing a cheque at a bank, buying groceries, all those everyday transactions that we do on automatic pilot he re-learned to do the Swedish way. For details read the book. He did learn to speak Swedish, by the way.

For the literal minded, yes there is quite a lot about fishing the book. It is Brown’s hobby and some of the most lyrical passages in the book are his weekends tramping through forests to lakes, amid man-eating mosquitos, to find a place to fish at sunrise, observing the breeze in the trees, the light on the water, the insects in the air. His father taught him to fish and he teaches his son.

The Sweden that Brown describes is all rather normal. Some people grizzle about taxes while cashing their pension cheques, denounce overpaid sportsmen while cheering them on. It is neither the paradise of its many rhapsodic admirers elsewhere, nor the putrid cesspit of depravity portrayed all too seriously by some krimi writers. It is no Midsomer!

Andrew Brown

Andrew Brown

He returned to Sweden as a journalist and covered some of the aftermath of the murder of Olof Palmé in February 1986. There is superb thriller that springs from that event, ‘The Death of Pilgrim’ (2013). Of course, the conspiracy at the heart of the plot is simpleminded, but the performances and tension are very well done without the gratuituous gore and violence of some Nordic thrillers on screen, like ‘The Bridge.’ However, I found the time shifts back and forth threw me more than once, the clothing and hair styles were not enough to indicate to me the context. Brown, to his credit, does not compare Palmé’s murder to that of Jack, but the aftermaths are certainly similar, the desire for meaning, and the desperate desire for there to have been a conspiracy to give the act meaning.

‘An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government’ (2001) by William C. Davis.

The last days of a regime.

Regimes come and go. In most places in the world the change is rocky, ragged, and rugged: Mubarak in Egypt, Allende in Chile, Hitler in Germany, Amin in Uganda, Franco in Spain, or Peron in Argentina. Mobs in the streets, armed police off the leash, fires breaking out here and there, hastily packed bags, the Swiss account numbers memorised. It is even more difficult when there is a war on with marauding raids, artillery shells in the air, and masses of troops on the move.

That is the subject of this book, the transition of the government of the Confederate States of America out of existence from February 1865. The hour finds the man, Italians sometimes say, and this hour found John C. Breckinridge who is the major character in this telling.

An honourable defeat, as in the title, would mean the best possible negotiated terms for the men of the Confederate Army and Navy, e.g., that they would be allowed to go home and not be imprisoned or otherwise punished and also that civil order would continue even when the war ended, i.e., that the state governments would continue to maintain law and order, protect banks and private property, dams, bridges, roads and so on. None of this could be assumed, it had to be brought about…somehow. It also meant that the army would not disintegrate into bands of armed men preying on the civilian population.

An honourable defeat also meant that none of the tens of thousands of armed men pledged to the Confederacy would be encouraged by word, deed, or silence to resort to partisan or guerrilla warfare. That is. when the government capitulated, all its loyalists would lay down their arms. There would be no further resistance.

In return for that guarantee there would be no reprisals against individuals. Breckinridge also wanted the units of the army to remain together and march home, i.e., the Fifth Mississippi infantry regiment would march back to Mississippi en bloc and put themselves under the authority of the state government as a militia to keep order, if that were necessary, and the looting and banditry that occurred in Richmond and environs so quickly after Lee’s withdrawal made this a real possibility. Indeed if the units simply broke up individually, the fear was that some would turn to banditry, think of the James brothers. Even those who called themselves partisans would be a greater threat to Confederate civilians than to the Union army, e.g., the James brothers when they rode with William Quantrell.

To bring about an honourable peace was difficult, first, because the elected president of the constitutional government of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, did not accept defeat was inevitable. Second feelings ran high after years of death and destruction, would anyone listen. Third, getting any message out was nearly impossible given the destruction of railroad and telegraph lines.

A major part of this story is the intransigence of President Davis for whom every reverse meant only that others had to redouble their efforts and make more sacrifices. Under the blows of defeat, he increasing retreated into a silent shell, but when he did speak it was the same message of more effort, more sacrifice. Even when resistance would serve no purpose he would not accept the personal humiliation of defeat, at the cost of the lives of many others.

During most of the flight of the Confederate government from 2 April to the end of May, Davis was lost in a cloud of despair and denial, leaving Breckinridge to exercise the executive powers remaining to the government. These powers were few but they were not negligible for those affected by them. Chief of these was to maintain social order, but also extended the preservation of and then the orderly disposition of government property. He was de facto acting President.

President Abraham Lincoln had refused to recognise the Confederate Government and he would never treat with it in any way. Yet Lincoln’s murder changed everything, for the worse, and meant that the Federal government was even less likely to respond to any overture from the Confederacy.

That the result was as peaceful, harmonious, and orderly as it was, the author credits largely to the efforts of John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875). He was a moderate from Kentucky with a distinguished political and military career. After a term in the United States Senate he was Vice-President in the administration James Buchanan (1857-1861). He was a candidate in the 1860 presidential election, one of four, and he won most of the Southern states, and so had a national reputation. After the election, won by Abraham Lincoln with far less than a majority of votes, Breckinridge returned briefly to the United States Senate.

John C. Breckenridge

John C. Breckenridge

He had served in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1847, as did so many other Civil War soldiers did. When the Civil War loomed he was commissioned a brigadier general to raise Confederate troops in Kentucky where his family name was widely respected. During the war he rose in rank to major-general of the CSA and served at Shiloh, Stone River, Missionary Ridge, and New Market. Like everyone who had to misfortune to serve with Braxton Bragg, he was sidelined because Bragg, being one of the few with any influence over Jefferson Davis, convinced Davis that Breckinridge was disloyal. Go figure, after reading that list of battles.

Despite being in sole command at one of the few battles Confederate arms won in 1864 at New Market, he was relieved of command. Then in a desperation move, Davis appointed him Secretary of War. It was desperation because no one else wanted or would take the job, and Davis perhaps thought he knew and could control Breckinridge with threats of censure on the the trumped-up charges Bragg had lodged. In this case as in all others, Davis was no judge of men (and perhaps not of women either). Breckinridge took the assignment exactly because he knew the end of days was coming, and he hoped to see an honourable peace as outlined above, and would work hard and intelligently to achieve it.

While the Confederate government remained in Richmond in February 1865 Breckinridge schemed, planned, plotted, and conspired with likeminded others to pressure Davis to face facts and seek peace. It is both heartening and depressing to see that their efforts were constrained by respect for constitutional provisions setting forth presidential powers, upholding states’ right, making supreme the civilian control of the army, and so on. Breckinridge himself was so rule-bound and though he found others who agreed with him about the need to seek peace now, they were also rule-bound. Still others were unwilling to take a position because they still hoped for some benefit from the situation. Even in March 1865 there were some Confederate Senators who aspired to succeed or replace Davis. The ego drove some to hope to be themselves President of the Confederate States of America even as it dissolved. (Pedants note, Confederate presidential elections were scheduled for 1867.)

But Breckinridge never had in mind a coup d’état which would only create more dissension, animosity, and confusion. He and all he involved adhered to the letter of the Confederate Constitution. While the most prestigious figure in the Confederacy General Robert E. Lee agreed with Breckinridge, this demigod would not overstep the chain of command. He reported to Davis and took his orders from Davis and he would not depart one iota from that, though at the same time he would lay out the unvarnished truth of the situation to Davis in his reports. These Davis would hear in silence and as always thereafter speak of redoubled efforts. Breckinridge spent several twenty-four hour days trying to coax and coach Lee into submitting a written report that implied, if did not say, surrender. Lee would never go quite that far. The conclusions to be drawn from his reports were the responsibility of his political masters.

Breckinridge tried at the same time to put together a coalition Senators and Representatives to arouse the Congress to ask the President to report to it and during the subsequent debate the peace initiative could be raised. He could not quite gain the support of the right individuals or in sufficient number.

He also tried winning over this half-a-dozen cabinet colleagues to speak as one to the President to seek peace. Some were so jaded by then as to be indifferent. Others kept alive their own ambitions, if not to succeed Davis, then to return to a political career in a state. One was a complete David sycophant. To win one man over was to alienate that man’s rivals.

He also tried to find a way for the State Government of Virginia to recall its citizens from service in the Confederate States of America armed forces, thus emasculating them in the East, and then for Virginia to secede from the Confederacy on the assumption that other states would have to follow that example and so bring an end to the fighting. The Confederate Constitution recognised state sovereignty.

To sum up, Breckinridge tried six or more different approaches, singly and in combination, to create a coalition for an an honourable peace in the Confederacy. He tried cabinet. He tried the Senate. He tried the House. He tried the state of Virginia and later North Carolina. He tried the leverage of General Lee’s prestige. He tried, later, General Joseph Johnston’s last remaining army as leverage. He tried some of these avenues more than once and several in combination.

He tried to influence Lee to sign his order of surrender on 9 April 1865 as Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate forces, a hollow title Davis had bestowed on him in earlier. Breckinridge thought that nomenclature would justify the end of hostilities across the board. Instead Lee directed his order to surrender to his field command, the Army of Northern Virginia in his General Order Number Nine. He felt he had no larger authority to dictate to others in Mississippi, North Carolina, or Texas.

That might have been enough to keep a normal man busy, but while Breckinridge was doing all of this, and more, he was also managing the largest, most complex, and important department of the Government of the Confederate States of America, accomplishing feats of provisioning, storage, and distribution that had baffled his predecessors. Lee commented on the irony that his army had never been so will stocked with food, uniforms, and munitions as it was in the last few days of its service. That fact he attributed to the labours of Secretary Breckinridge.

To no avail, and on 2 April, General Lee withdrew the scarecrows of his army from the earthworks at Petersburg and fled south and east to avoid the closing jaws of the Union army. The government now had to evacuate Richmond which was open to Federal assault. Breckinridge had no general authority, but as Davis was nearly comatose with shock, he took it upon himself to organise the selection of archive material for destruction or shipment, the opening of warehouses to distribute the food and clothing that remained, before the Federals arrived and took them, the burning of bridges, the assembly of wagon trains to put the government into flight, and to piece together the railway trains to transport the cabinet and the treasure (perhaps $500,000). He also managed to raise a scratch force of horsemen of several thousand to escort the wagon trains.

By default Breckinridge became the de facto manager of the government’s flight and gradual decay. All the while he continued to search for a way to produce an honourable peace.

Nothing was easy and nothing worked smoothly. When they came at all, the trains were five or six hours late. Roads were impassible in the mud of early spring rains and horses were near starvation to begin with. People got lost in the confusion. Mobs choked streets in fear of the coming Federals. Looters got to work. In the confusion arsenals in Richmond were destroyed, setting fire to much of the city. There were fears and rumours of an armed slave uprising fomented by the Federal cavalry.

Apocalyptic it was.

There was no plan except to get the government out of Richmond. Breckinridge hoped it still might bring an honourable peace, though the capacity to do so diminished with Lee’s surrender, while Davis spoke of, take a guess, redoubled efforts. The merry-go-round stopped briefly at Danville Virginia. The cabinet set up shop in front parlour of a private home. Davis wrote a message to the people calling for…redoubled efforts. Breckinridge gathered intelligence about the armies and tried to find a way to make peace through the state of Virginia or then North Carolina.

Federal cavalry was out in force looking for this government on wheels, and Danville was so obvious a place that burned bridges or no, it had to move on, to Greensboro in North Carolina and on and on further south.

There was no master plan and it was only Breckinridge’s initiatives that kept the wagons rolling. The group started with thousands of men, soldiers and civilian officials, and their cargo and camp followers, and other citizens terrified of rumours of the Federal atrocities (attributed to black troops, who truth to tell were themselves victims of atrocities).

The purpose of the flight changed as time went on from (1) negotiation, (2) maintenance of social order, (3) personal safety and exiles of Confederate Government officials, and (4) to assist Confederate soldiers who had surrendered to get home, (5) to settle the outstanding debts of the Confederate government with that dosh. The disintegration of Confederate armies rendered negotiation moot. Social order did break down. As soon as the caravan left a town, the government stores, offices, and warehouses as other public facilities were ransacked, looted, and pillaged. As word spread of the comprehensive defeat, other civilians took to the hills, partly to escape the feared Federal atrocities and also to escape the likes of Quantrell.

There was never any intention to take the government into exile, though some of its individual members might go into exile to avoid Federal retribution, especially for the murder of Lincoln, which many in the North thought was a Confederate deed.

Breckinridge tried, on the retreat, to preserve War Department records. Those left in Richmond were put into fire proof safes, not all of which proved to be fireproof. As they shed wagons, railway cars, and load, more and more paperwork was left behind. Much of this he tried to leave in the safes of local banks, and in other cases put into chests and buried. In part he wanted the historical record to show what had happened. This accuracy of record became even more important with the murder of Lincoln. He wanted to demonstrate that the were was no involvement of the Confederate War Department.

He also held onto some of the paperwork long into the journey to the annoyance of some in the group because it slowed the pace. Among the papers he kept at hand were dossiers, documents, charge sheets, affidavits, testimony that identified Confederate officers who had committed atrocities, usually on black Union soldiers. While en route he tried to locate one such officer who had killed helpless black Federal prisoners. This had occurred in an area where Breckinridge had nominal command on paper, though he had become Secretary of War and had left the department, his name was still on the letterhead. That made it personal since these murders had occurred in his name.

Breckenridge authorised the dispersement of the treasure along the way to pay off soldiers in the escort, to buy provisions, shoes, and clothes for paroled soldiers trying to get home, and to buy medicine to treat wounded men. He himself took the soldier’s pay of $26.60 out of the hundreds and thousands he had in hand. This was the amount all soldiers. regardless or rank were paid, Several of his cabinet colleagues were much more grasping according to the assiduous financial records kept even on this trail of tears.

The trip goes on and on, as the group splits, and takes different routes. At the end of May after some weeks in the swamps of south Florida, Breckenridge made it to Cuba, His last act as an official was to appeal through the resident American journalists in Havana for all Confederates to lay down their arms and accept the result. After some years in exile he returned to Kentucky and lived quietly, refusing an invitation from President U.S. Grant to re-enter politics. His health had been badly damaged by war wounds and then the diseases and hardships of the flight through Florida.

Early in the odyssey he become the first and only Secretary of War to lead troops into battle when he led the cavalry escort in a counter attack on Federal pony soldiers who threatened the column (p 99). Would contemporary Secretaries of Defense be less likely to put boots on the ground in combat if the boots were theirs? Or their children’s? The answer is obvious: Yes.

Our author says Breckinridge, as a former Vice-President (1857-1861), was the most senior political figure to side with the Confederacy (p 167). Former President John Tyler (1841-1845) did so, too, serving as a Congressman from Virginia in the Confederate House of Representatives until his death.

A stylistic quibble, ’Secretary of War’ should surely be in capitals since it is a title, like a proper name but it is not.

I read this book near the publication date and when the upheaval of moving brought it to light again, I put it aside and dipped in, but once in I kept going since it is such a compelling and fast-moving story with a cast of characters from the ever-smiling in the face of adversity Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, the taciturn President Davis, the demigod Lee, the clever temporiser Joseph Johnston, the man of the hour Breckinridge, and many lesser known figures who rose to the occasion.

William Davis

William Davis

One such instance of rising to the occasion occurred when a month into the flight, Davis summoned the brigade commanders of the 2,500 escort troops to an audience. When they assembled, Davis spoke of redoubled efforts and still more sacrifices as they stood in dumbstruck silence. Davis expected them to salute in agreement. He did not assemble them for advice or debate but to agree with him and to obey.

As the silence prolonged, he finally asked them to respond. To his credit, the senior man of the five brigadiers, George Dibrell, stepped forward and said it was hopeless situation and useless to ask more of his men who had continued this long out of personal loyalty. In turn, the other four concurred. Davis paled, and as always when confronted with contradiction went into his shell. There was more silence. Finally, Davis’s manners returned and he dismissed them only later to bemoan their lack of resolve. All praise to General Dibrell for calling a halt to the madness.

‘Spear’ a film by the Bangarra Dance Company.

Our last Sydney Festival gig was this film. Through images and dance it conveys the ambiguity of being an aboriginal in contemporary Australia. Note it is not a narrative.

Unlike some of the annual breast beating about Aboriginal Australia that usually occurs on Australia Day and then is quickly filed away, this film is direct without either villains or victims, although there are some cringe-making moments.

A young man undergoes an initiation ritual. Into what? Is he affirming his aboriginal heritage or leaving it behind? Should he do one or the other? What is the past in Arnhem Land? What is the future in Redfern? There is some symbolism interspersed with some very literal and brutal honesty.

Some of the emotions are expressed through dance, somr through symbolic figures. and once and while in words. Mostly it is introspective with some aboriginal language, music, and bird calls. It is spare.

The boy witnesses much and is left to make his own choices, day-by-day.

There was much that I did not get, like the upside down man, but the movement, the intensity, the creativity, they were more than compensation. There is some film on You Tube for samples.

We have seen some of Bangarra’s other productions and found them compelling. Ditto this.

‘Double blind,’ modern dance, Sydney Festival 2016, at Carriage Works, Redfern

We loved the wit, creativity, energy, commitment, and choreography by Stephanie Lake. All in about an hour. Nicely done.

The sounds of buzzing electricity coveys human interactions and emotions in the reactions of the dancers.

It is divided into segments and it might have been nice to have them named in a program if for no other reason than to allow a viewer to reflect later on what has been seen.

Some of the early segments were intriguing and amusing: they seemed exploratory. The opening segment showed the energy between a young man and a young women, part playful and part serious. It drew in the audience, a full house it seemed in; l leaned forward, and I was not alone.

During one unpleasant segment in the middle, a voice-over said the word ‘experiment’ in a European accent. Moreover, the static sound in this part was taxing to the ears, like the screech many of us would fear in Room 101. (Get it?)

Stephanie Lake

Stephanie Lake

The closing segment was a reminder of Dr Frankenstein testing the capacity of electricity to bring creatures to life and to bend them to his will.

The press notes say that the choreographer was inspired by the Stanley Milgram experiments of the 1960s, which have been so widely reviled as to enter into the popular culture where all things undergo an alchemical transformation to the simple and sensational.

Download file

Should I suspect that the inspiration was the film ‘The Experimenter’ (2015), which is, well, as they say, based on a true story, and inspired by Milgram’s original studies published in psychological journals culminating in the book ‘Obedience to Authority’ (1974)?

The apparatus to which the dancers were often tethered resembles the film prop. That much is clear.

The Yale University experiments both made Milgram’s reputation and destroyed it.

Stanley Milgram

Stanley Milgram

Made it, because he thought they showed the willingness of ordinary men (they all were men) to inflict suffering on other ordinary men at the behest of an authority figure, and so the results have entered the popular consciousness: We all have a little evil torturer within ourselves. In reaction, he became a celebrity social scientist on the talkshow circuit, rubber chicken speaking tour (on which I saw him in flesh), and head-hunted by universities to add glamour to their funding raising.

Destroyed it, because in the inevitable backlash (read envy) there was a competitive rush to find victims of Milgram himself and to feel sorry for them. A number of psychologists concluded that the ordinary men who participated in Milgram’s experiments had suffered anxiety and fear in ostensibly inflicting pain on others. He became a persona non grata and the Olympian American Psychological Association enacted research protocols to prohibit research that might stress subjects.

‘Blind’ and ‘double blind’ have specific meanings in research. In general ‘blind’ means that one person does not know the identity of the other. When the paper I submit to a journal is assessed by editorial readers I do not know their identity; I am blind to their identities. Sometimes they are permitted to know my name on the cover sheet of the submission. That is an example of ‘single blind,’ or ‘blind.’

When the cover sheet is removed and the manuscript is otherwise cleansed of any information that might reveal my identify then the editorial reader does not know my name. Voilà! This is ‘double blind.’

Human ingenuity can find ways to signal identity through this process and well informed editorial readers make their own inferences, but that is the form, which is practiced very generally these days, made easier by digital communication which widens the net at both ends, submissions from around the world which and sent to editorial readers around the world.

In experimental work like Milgram’s ‘blind’ means that the subject does not know that he (I am going to stick with men because they were Milgram’s subjects) does not realise he is the one being studied. These men were told that that the study was about how other persons reacted to them, in that sense they are part of the research team and not themselves subjects. Ha, ha, ha! They are thus ‘blind’ to the purpose. In this context ‘double blind’ would mean that the experimenter also does not know that the subject is the subject, i.e., whether a member of the control or treatment group, for those who know the terminology. This makes sense in some studies and it cancels any prejudice by the experimenter. A quick look at Milgram’s book does not yield a reference to ‘double blind.’

To return to the dance, perhaps ‘double blind’ means not knowing whether one is in charge or is a victim, is master or servant, is boss or employee. Perhaps those who think they are in charge are in fact being themselves manipulated by still others. That those who are running the machine are in fact being run by the machine. That is how Michel Foucault would put it.

Did Milgram prove what he said he had proven? That evil is within every ordinary persons who will blindly follow any authority. Really? Consider the context.

He did the bulk of those experiments while the streets in American cities like New Haven (Yale) and New York (NYU) where he did his studies were often choked with civil rights demonstrators opposing authorities equipped with pressure hoses, attack dogs, automatic weapons, tear gas… need I go on? When the civil rights protestors were recovering from the beatings they suffered at the hands of authorities, the streets were occupied with anti-war protestors opposing the war in Vietnam. Need I go on? In fact, both of these movements preceded his work and he took no notice of either.

Were his subjects everyman? They were those who answered the newspaper ads, and they were single men who wanted the fee for participation, small though it was. Hardly a cross-section of society. Milligram was not a sociologist so there was never any profiling of the subjects. I said ‘men’ above about the early advertisements called for ‘men’ and the wording of the reports in journal articles and in the book is always that. Nothing in the experiments went into differences among the demographic characteristics of the subjects by age, education, sex, occupation, and the like.

There is a very disturbing book about the evil within, and that is Christopher Browning’s ‘Ordinary Men’ (1992) which is a study of an German police battalion in Poland in 1940s implementing the Final Solution. Grim, indeed. But what emerges in the short book is that these were pretty ordinary men even in that terrible situation, and very few of them were zealous murders, but that some were and they were off the leash, while the others looked away. I learned more about evil from Browning’s book than Milgram’s and part of what I learned is that no generalisation works. I also learned that looking away is the reflex. It may be the best one can do.

Yes, I have published on this in ‘Orders and Obedience: Structure and Agency,’ International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 26 (2006)7-8, 309-325. Dial it up and be enlightened.

Milgram was a brilliant experimenter and his other studies have long been overshadowed by this series. He himself rather encouraged that, I suppose. But he did many others about crowds and queues all the while observing the Milgram rules made by the gods of the APA.

There is a novel that likewise claims inspiration from Milgram, namely Will Lavender, ‘Obedience’ (2009).

I liked reading it but the line to Milgram was tenuous.