Walt Disney was born in a small railroad town in Missouri. It was a water stop for trains, and he retained a lifelong fascination with trains which led to Disneyland.

He was a bright and industrious young man who had seen too much farm work as a boy to want to be a farmer. In his desire to escape the physical drudgery of farming he is akin to Huey Long.

His distinction in the early animated cartoons was the effort to put emotion into the toons. Whereas rivals like ‘Tom & Jerry’ or ‘Felix the Cat’ were drawings whose heads exploded and then re-assembled, Disney started putting puzzled or hurt expressions on the face of Mickey Mouse.

Walt Disney never stood still. He went from one project to another. He was a workaholic and worked late into the night, even when he was the proprietor of Disney Studios, he was frequently alone in the Studios at midnight.

He was also an innovator and a demon for ever higher quality in drawing, animation, movement, colour, and more. Innovation and quality meant that animators wanted to work for him, and many left higher paying jobs to work at Disney Studios to learn more of the trade. One of his innovations was staff development, as we would call it today. The author also credits Disney with the concept of the storyboard, now used in every movies industry in the world.

He could be volatile. There are many claims that he was tyrant or a racist but this author finds no evidence for either claim. Though the swings of business meant that at times, loyal and able staff had to be dismissed because there was no money to pay them. He was categorically anti-union and paternalistic as an employer. He equated unions with communism as did too many others during the early days of the Cold War, and he was a friendly witness before HUAC. Yuk!

Despite the temptations of Hollywood he was ever loyal to his wife. The author implies that Disney broke profitable business relations with some actors and directors whom he thought, perhaps wrongly, did not treat her with respect. After their first child she had several miscarriages and that led them to adopt a second child.

His brother Roy ran the business side, but always deferred to Walt’s creativity. When Walt used company money to build a scale model train as a hobby, Roy did point out that the stockholders would not accept that. To justify the scale railroad it became a company project, and led to Disneyland.

Roy Disney

Roy Disney

Disney visited many amusement parks and found that those aimed at children bored adults and those aimed at adults bored children. In both cases the boredom meant a short visit. By combining amusements for both adults and children, the visits would be longer, and patrons would spend more money. To facilitate longer visits and more spending, Disney introduced suff development to train guides, operators, vendors in dealing with customers. Another Disney innovation is queue management.

I was surprised to learn how fragile the Disney empire was even in 1960s when it seemed to be an American institution second only to the White House. Since Walt was always pushing ahead to another project – more and better cartoons, television, movies, Disneyland, Disneyworld, EPCOT (which is not mentioned in this book), the finances were always stretched. One sign of this is that the brothers Walt and Roy lived modestly compared to the Hollywood standard of the time.

‘Snow White’ (1937) made mint and set a standard that he never equaled. The single-minded determination to make a feature length cartoon, and to make it an artistic and commercial success is one of the most interesting episodes in the book. The banal description of ‘Snow White’ on the InterNet Movie Database belies what a groundbreaking work it was in 1937.

Disney set out to top that with ‘Fanastia’ (1940) but the technical problems were so great that this project devoured money, and in the desperation to get a product and some financial return, it was neither an artistic nor commercial success. Disney did not always get it right.

Disney made the transition from cartoons to live action films thanks to World War II. When the war began the Department of Defense contracted Disney Studios to make training films, which were at first technical, involving a lot of diagrams and animation, but came to involve actors showing how to repair an engine, or repair a tank tread.

‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ (1954) and ‘Davy Crockett’ (1955) both made money and attracted acclaim. Genius as he might have been, Disney did not follow-up either successfully. He was always reluctant to hire expensive Hollywood directors and actors and ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ is the only time he did. When ‘Davy Crockett’ made even more money, he decided he did not need high priced talent. I do remember that cap!

He seems to have misunderstood the success of ‘Davy Crockett’ because he then cast its star Fess Parker in a series of duds. They were duds because, in effect, Parker was cast as a supporting actors to, by turns, a group of children, a dog, and a bear. When his contract came up for re-newal, Parker quit.

By the way, he picked Parker out of the film ‘The Thing’ (1951), and as an unknown, Parker came cheap.

The 1950s and 1960s television series of Disney was designed to promote Disneyland.

There was a lot of office politics in Disney Studios. Getting his attention was key but he had so many projects going, including constantly rebuilding and expanding the studio that his attention was scarce.

He travelled a lot in the States but also in Europe. The honours and awards poured in but he remained restless for the next project.

There is a good deal in the book about the technical aspects of animation. More than I expected in a ‘Life.’

MIchael Barrier

MIchael Barrier

Michael Barrier played Lieutenant De Salle in Star Trek, the Original Series episode ‘Memory Alpha.’

De Salle

De Salle

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘Elmer Gantry’ (1927) by Sinclair Lewis

In this novel Lewis recounts the life and adventures of the title character with the sledgehammer subtlety that marks all of his work that I have read: ‘Arrowsmith’ and ‘Babbitt.’ In a generous mood, I will call it satire rather than sophomoric caricature.

Elmer Gantry is a self-centred charlatan who starts out a travelling salesman selling anything and everything from snake oil to farm machinery to anyone with a dollar. He has a gift of the gab and personal charm that makes him a success, but he also has many faults that undermine that success, chiefly the faults of whiskey and women.

He learns to sell religion and salvation, and not only does that make money, but it also gives him a power that is so satisfying that, to some extent, he controls his faults. Indeed, he stops drinking altogether. Gantry enjoys the competitive element in drawing crowds and raising money against other rival churches and barnstorming evangelists. Most of all, he enjoys manipulating others, for which he seems to have a gift, i.e., people believe what he says, even those who should know better.

He uses and abuses believers, fellow preachers, and several women.

There are a few bon mots and a couple of well-turned phrases, but for three hundred pages the prose is, well, prosaic.

The telling is episodic and relentless in demonstrating Elmer’s one-dimensional unscrupulousness and complete amorality. There is no limit to Gantry’s mendacity, duplicity, and deceit. There is never a qualm of conscience. Never does he do something for another but always for Elmer over the forty year period covered in the book. He never seems to grow or to change. He switched addiction from booze to power, discovering he could still have women on the side. It becomes one note repeated again and again.

The only people who see through him are either bookish ineffectuals or the blackmailers, who are themselves so corrupt that they have to back off.

The underlying theme is that religious people are all fools in one way or another. Like those without religion, Sinclair cannot imagine what faith means to others.

There is one dramatic moment when Reverend Pengilly asks Elmer why he does not believe in God at the end of Chapter 27 and it not resolved and so becomes a non sequitur.

By far the most interesting character and the best part of the book concerns the strange evangelist Sharon Falconer. She is far more compelling than Gantry himself. She also seems to be sincere in her mission, though she likes the money, too. Doing well by doing good, as Ben Franklin did say. She seems to be a split personality. Lewis kills her off. That is approximately the middle third of the book.

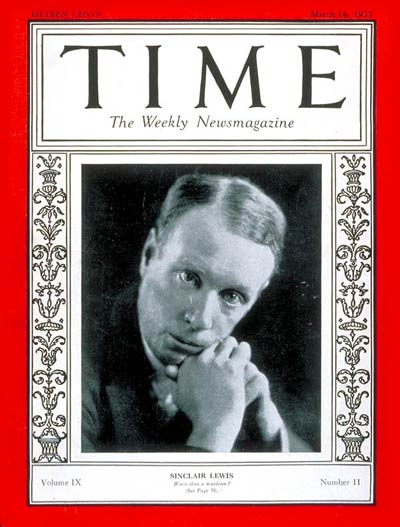

Sinclair Lewis on the cover of Time Magazine.

Sinclair Lewis on the cover of Time Magazine.

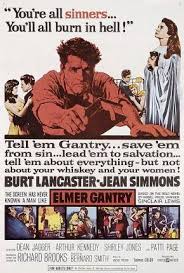

I retain a very strong recollection of the film ‘Elmer Gantry’ (1960), but had never read the book. In memory the film concentrates on Falconer. Time to do the homework. While travelling in Turkey, I downloaded it to the Kindle and read it.

A lobby poster for the film.

A lobby poster for the film.

When I started reading the description of Elmer at the beginning brought to mind the very actor who embodied him in the film, Burt Lancaster. It seemed as though, Lewis created Elmer cased on Burt, though that is chronologically impossible.

The mysteries and treasures of O’Connell Town. 2

The Bougainvillea is a beautful and deadly thing. Those that have been near one, know what I mean. Its name comes the French admiral who commanded the mission that lead to the first European description of this fecund, tropical beauty. We had one for a while, in a pot to contain its growth. Even so it grew over the door to the laundry, and one of us had to go. Either the Bougainvellea or all of us. Those thorns are large and small, each sharp. Owie!

These two are on Hordern Street in O’Connell Town at Shane’s house.

The colours are as intense and vibrant as the thorns are sharp and penetrating.

Beautiful to look at — from a safe distance.

The mysteries and treasures of O’Connell Town. 1

For the cognoscenti O’Connell Town is the historic name of an enclave within the larger historic Bligh Estate that once encompassed most of contemporary Camperdown, Annandale, and Newtown. There are no remnants of the Blight Estate left in the area, or so I have been told by a fellow gym user who has lived in O’Connell Town for forty years.

Having moved into this area, while dog walking, going to and from the gym, and to the station and bus stop we are learning about O’Connell Town.

We noticed this display on the corner a few days ago. Take a look.

Look closer. It is an album of photographs blue tacked to the outside of a house. See.

There were twenty photographs of assorted subjects.

Then one day, one was missing but the rest remained. My hands were full and I did not get a picture. Then a few days later they were all gone only leaving behind the blue tack.

Huh? What was that about? You can tell me.

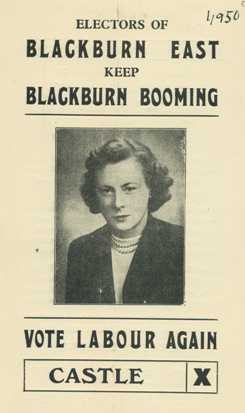

The Red Queen: Barbara Castle

Reader, a test before we begin. Did you ride in an automobile today? Did you wear a seat belt?

If so, then you owe something to Barbara Castle neé Betts (1910-2002) who was a Labour Party stalwart for two generations. She radiated conviction, energy, and determination. The Red Squire Stafford Cripps said in the 1940s she was a prime minister to be, but that was not to be. By the way, Cripps was not an easy man to impress for he had few good words for several others who did become prime minister.

By Lisa Martineau in 2011.

By Lisa Martineau in 2011.

She was lefter than thou yet from a public school, Oxford, and championed radical causes in the 1930s. That together with her red hair invited the sobriquet ‘The Red Queen.’ A title she accepted with pride.

Her achievements were great and small, from securing a ladies’ toilet near the chamber of the House of Commons, a feat other women had been unable to perform. It was, inevitably, called Barbara’s Castle. She also led the charge against turnstiles on public toilets for women, starting with House of Commons. There were no turnstiles on mens’ toilets, yet they were not pregnant, towing children, or carrying shopping. Of course, Margaret Thatcher fixed all that gender inequality by doing away with free public toilets, making it pay if you want to go.

At the other end of the continuum, she was a founder of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and a tireless exponent of the New Jerusalem that Socialism undiluted offered. She worked just as hard to speed British exit from the fifty-seven colonies it held in 1945. To that end she travelled to many of them, particularly in Africa. I rather suspect the parliamentarian played by Flora Robson in the film ‘Guns of Batasi’ (1964) was inspired by her. By the way, Richard Attenborough is electric in this film.

With the flaming red hair, blue eyes, and resonant voice that emerged from this petite woman, she was spellbinder at the podium. Even lifelong enemies like Hugh Gaitskell said he found himself nodding when she argued cases he opposed.

As a minister of the crown she had a deadly eye for detail and put in nineteen hour days and expected the same from the public servants. When they could not, or would not, match her pace she hired private consultants to add to the workforce. One of her great achievement as a minister in four departments was to hire economists. Hard though it is to believe but the ministries of Overseas Aid, Transport, and Health employed no economists until she arrived. Much as the Sir Humphrey’s of the day disliked her, they found her to be a champion for the department unlike any other minister. As one cabinet colleague, and later prime minister, James Callaghan, another lifelong enemy, said, she simply would not shut up until she got her way, and she often got her way because it was the only way to shut her up. Even in times of declining budgets she always boosted the allocation to her department by brow-beating cabinet and won most of the border disputes with other departments.

There is much to like and to admire in Barbara Castle. It is also true that she was completely one-eyed: Socialism was a planned economy, nay, a planned society. Socialism will give people what is good for them whether they want it or not, whether they think it is good or not. There is a zealot there for whom the problem may require that the people be re-educated. She had no patience, no toleration for those who did not accept her vision of the planned society. Guess who would be the planner in chief.

She detested the sewer socialist in her party in the 1940s and 1950s. ‘Sewer Socialist’ were those who wanted and accepted small gains, like clean water, a working sewer system, modest wage increases, affordable housing, industry pension funds… These incremental changes she dismissed as distractions from the larger, main game of social (r)evolution. When Clement Atlee staked his Party on the National Health Service, she thought it was trivial, and said so. The whole of the planned society had to come first before any of its parts.

When she visited the Soviet Union in 1937 it was the Light on the Hill, and she said so forever thereafter. She was not the only intellectual who saw what she wanted to see in the USSR in the 1930s, see Paul Hollander ‘Political Pilgrims’ (1997), but, while many others recanted, admitting their errors, she never did. Indeed in the 1970s she was still defending the paeans of praise she had sung to Comrade Stalin in justifying the Show Trials. While she advocated abortion in Great Britain, when Stalin outlawed it in the USSR, she rushed to the typewriter to justify his action and extol his wisdom.

Successive Labour Party leaders from Clement Atlee, Hugh Gaitskell, Harold Wilson, Jim Callaghan, Michael Foot,Neil Kinnock, Tony Blair, and Gordon Brown found her a loose canon. She certainly blundered as she steamed ahead, arousing expectations that were impossible to fulfil in constituents, in African nationalist leaders, and in many others. But nothing is accomplished if nothing is tried. She tried, if she was trying. Like Moses Malone, whose recent passing I noted, she had ninth and tenth effort, not just second and third effort.

When she advocated British withdrawal from Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios of Greek Cyprus invited her to Athens for private talks. She was all but forbidden to go by the Party leader, by the Foreign Office, by the Ministry of Defence; she went. The professional diplomats had been unable to find an accommodation in Cyprus for years, but she did it in two weeks. The arrangement that led to the Green Line which still partitions this island emerged from personal intervention.

She did not play by the rules, and that enraged many, even some who were close to her like Harold Wilson.

One of the rules she despised was making deals. She wanted everyone to agree with her, and she asserted her case from first principles, not mutual interest or advantage. Nor would she delay until the timing was more conducive. No way. It was always now or never!

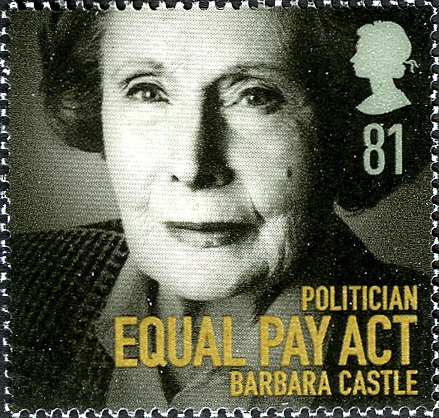

Though the author does not give it emphasis, there is a transformation when she became a cabinet minister. She learned that half a loaf makes a good meal. Compromise today, for tomorrow is another day. As minister of transportation she revolutionised what had been a moribund backwater. In so doing she incurred tsunamis of abuse. She legislated seat belts, breathalysing, speed limits, and other changes that vested interest denounced as a communist plot. The abusive letters, death threats, systematic smear campaigns, jostling on the street, hectoring from the public gallery in the House, she endured from individual motorists who had a god-given right to drive drunk at high speeds, automobile manufacturers who claimed they would be bankrupted by installing seat-belts, publicans, and brewers because breathalysing would and did reduce alcohol consumption. Oh, by the way, her measures also reduced road accidents, deaths, and injuries by 50%.

There was only one way for her, and that was up. She became First Secretary to Cabinet, an archaic title, which made her de facto Deputy Prime Minister to Harold Wilson. She learned to trim, to temporise, to compromise, to balance, to wait for the right time…all those things she denounced in Atlee, Gaitskell, and others in the 1940s, and 1950s. The Tribune group, and later Militant Tendency, in the Labour Party attacked her daily, and she learned what it was like to have marbles underfoot every hour of every day. Some may have seen one of the best political dramas ever, ‘Bill Brand, MP,’ from this time. I say ‘best’ because it got the politics right. In that respect it is comparable to ‘The Sandbaggers.’

Then she moved to labour and took on the Trade Unionarchy that was running much of Britain in the late 1960s. Rivalry between unions took the form of endless demarcation disputes and in effect put the entire county on an unofficial three-day working week (which later became official when the Tories took over). The days lost by strikes in the twelve months before she took over surpassed the total for the previous decade! By now she was less interested in a blueprint for the New Jerusalem and much more interested in sewer socialism, quite literally getting sanitation to work. While Prime Minister Harold Wilson sent her forth, most in the Labour Party opposed any effort to rein in the unions. She was comprehensively undermined, as she had undermined others in earlier years, and failed.

Fail and move up, that is an old adage in Brit politics. She was moved on to take charge of the NHS, rolling up her sleeves started to work reducing private medicine to zero. The doctors resisted, they struck. The winds of hyperbole blew. Once again she played Saint Sebastian, taking the arrows meant for Wilson. She wore away her opponents but the backbiting in cabinet reached new levels. Then Wilson pulled a rabbit out of his hat: He quit. Though she won her battle with the medicos, she was dumped by Wilson’s successor before she could conclude the matter.

She had no future with the new Prime Minister, Callaghan, whose hostility was open; he was a union man first and last, and saw no role for women out of the kitchen. Castle’s effort to legislate for equal pay for equal work for women and then the effort to increase the pay for nurses was anathema to organised labour in the day.

The unions and their bought-and-paid for parliamentarians attacked her even more savagely on equal pay than they had on her earlier effort to sanction illegal strikes. The hate mail, the threats, the denunciations were hysterical. She had to go, and Callaghan dismissed her in his first act after taking the oath while in the car. He did not even wait to get to the office.

She went to the backbench, where she was free to speak her mind. Did she ever! She got herself on every committee in Parliament and the Labour Party and tore into the Labour Government. She reverted to type: Lefter than thou. She hit the typewriter for the newspaper which loved seeing the Labour Party tear itself apart (again). The Tories had only to sit back and watch the fun.

The advent to the European Parliament led her to becoming a Member of the European Parliament where she quickly established a reputation as a demon for detail. She became the leader of the Socialist bloc.

In 1990 she finally accepted a place in the House of Lords, something she has turned down earlier, where she resumed her role as the Socialist conscience of Labour. Age did not weary her, as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown found when she lit into them. She died at her desk, reading legislation line-by-line which always did, looking the mistakes, inconsistencies, slips, and red flags.

The comparison has to be Margaret Thatcher. Ambitious, smart, driven, and similar in complexion and appearance.

Castle was something of a clothes horse, always careful of her appearance, always a man-magnet, with a taste for country houses and French champagne. There were no children. She never learned to drive a car. Her husband Ted, himself a journalist, led the cheering for her. In those days she still performed all the housewifely duties. She ironed, cooked, dusted, often while dictating into a machine.

It also has to be said that she endured the heavy hand, sometimes literally, of the uninhibited sexism of the time and place. Even the newspaper stories from the day make this reader today cringe.

We will not see her like again.

The author does have a distance from the subject, frequently pointing out Castle’s inconsistencies, volte faces, mistakes, and rapacious ego. But at other times it slips into the ‘Barbara could do no wrong’ tone.

For a book about politics there is precious little about the elections, especially in the 1960s and 1970s when she played a major role.

Too often the author shows Labour partisan colours. Calling everyone by the first name meant I got lost among the several Dicks, Jims, and Tonyes. There are some typos. Some broken syntax, well, sentences that even on a second reading did not compute in this reader. Some more editing would have increased its impact and shelf-life. I also wearied from the detail of this meeting and that but perhaps a Brit pol junkie would eat that up.

This detail of events though seems to somehow to obscure the person. Her number one supporter, husband Ted, died, and she kept going, inspired, she said, by Dennis Potter’s ‘The Singing Detective.’

I read this book on Kindle. I do find navigating the bookmarks hit and mostly miss and I have not yet mastered switching to Whisper. The Kindle edition has none of the photographs of the published book.

‘Dear Committee Members’ (2014) by Julie Schumacher

I read it in one sitting, stifling laughs, snorts, and chuckles as I went. Set in academe though it is, like ‘Dilbert’ it resonants with life in any large organisation these days. The drive for ever more meaningless detail and perfunctory documentation that is never used is endless and general. Nor is it only in academe that one part of the organisation thrives while another starves. Then there is the snivelling twelve-year old from Tech who mocks those he supports.

Professor Jay Fitger has long since made a separate peace with research and teaching, instead spending many a long day writing letters of recommendation for any and every one, each peppered with asides about life, his life, The universe, and the university that is grinding him to dust. An old salt, he knows many of his correspondents, been married to some, thrown-up on others, and takes that intimacy as licence to be ever more long-winded, circuitous, and explicit. Professor Fitger is surly, mendacious, anachronistic, energetic, and sharp along the edges.

His letters support students applying for internships (unpaid jobs), scholarships, two-week training workshops, jobs in mortuaries, summer jobs, places in a queue, and seminars taught by people Fitger despises but needs must, and for colleagues applying for tenure, part-time jobs, summer jobs in garage, meaningless awards, their own jobs twice in one year, honorary titles (more work for no money), and the use of the toilets where even that prerogative is limited. The point is, everything has to be applied for and every application must be supported by five letters of recommendation.

Fitger brings some of this load on himself since he never says no, and ends up writing in support of candidates — both students and professors — he does not know, nor want to know. along with those he knows and does not like. That is understandable. There are some colleagues, there are some students to whom it is far easier to say yes than no. If they want a letter it is best to do it, rather than try to talk them out of it. Safer, too.

His passing descriptions of colleagues brought tears to my eyes. Two-thirds of the members of his department bear the scars of long-term abuse from the university, mostly imagined but some real, and busy themselves tending to personal grudges like scraps of carrion on which they gnaw in the corners of the open-plan work space they now have instead of offices with doors. Few will survive the killing fields of administration in the next re-organisation. Fidget expects his department will be re-organised out of existence soon.

Against such threats to its existence there was the Department retreat where instead of discussing survival they argued for hours about the placement of a comma in a resolution that no one voted for when it was finally presented. Exhausted and frustrated, they turned to drink.

When not likening students to primordial ooze without individuality, Fitger says of one: she has endured the intellectual abuse and collective disdain for which this university is widely known, overcome administrative snafus of Orwellian proportions, and been penalised by other professors because she is his supervisee.

Though the best is perhaps the periodic correspondence with the campus Wellness Office about a disruptive student, one who terrorises the other twenty-nine in a discussion section, a fact deemed irrelevant to the Wellness Office, which repeatedly charges Fitger to be more supportive, understanding, and lenient. If not, then it is Fitger who is the problem! We have training courses for that! One more irritating complaint and off Fitger will go to be re-educated, Comrade Number One.

Julie Schumacher

Julie Schumacher

Class, there is further reading. Another tale told in letters is Mark Harris, ‘Wake up, Stupid’ (1959) which left me gasping for air in 1980, according to the records. Then there is Iain Pears’s ‘The Titian Committee’ (2004) in which the chair of the eponymous committee, despairing of achieving consensus among the fractious members of said committee, begins to murder them, one-by-one, in the hope that the survivors will be more pliable. As if! The survivors become even more determined to resist consensus. Evidence be damned!

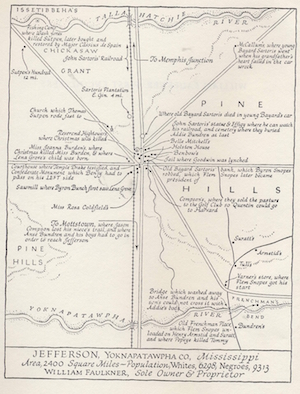

‘William Faulkner at West Point’ (1964) edited by Joseph Fant and Robert Ashley

In April 1962 William Faulkner spent a few days as a writer-in-residence at a college in a small town in New York state, West Point. The book combines the typescript of the story from ‘The Reivers’ which he read (including his hand-written emendations), and transcripts of several question and answer sessions with students and faculty.

It is overproof Faulkner and there is no stronger elixir. The moral purity of the man glows. By moral I mean his commitment to lift the hearts of readers with true accounts of the conflict within and between us. ‘Morality’ does not mean telling other people what to do; it means doing the best one can at what one does. Believe it, Faulkner says it better.

He acknowledged that his novels are uneven but he loves all his children, the crooked as well as the straight, as would a mother, and learns from them each. When asked about the parochial nature of his work, he admits it, and then goes on to the eternal themes of loss, love, onus, anger, belonging, challenge, and — most of all — comprehension. Asked to say which novel is his favorite, slowly he answered, as I knew he would, ‘The Sound and the Fury’ because it hurt so much to write it, and it still hurts ‘when I read a few pages of it.’ The implication is that a few pages at a time is all he can bear.

Why is the idiot Benjy the narrator in ‘The Sound and the Fury,’ he is asked? Is it because of his childlike simplicity? No, said Faulkner, though much more politely than that, it is because Benjy does not understand what he sees, and even so the novelist must try to make it understood.

Asked about Southern racism he replies that it is a terrible disease to be eradicated by education, but it won’t be as easy as eradicating polio. No, not the education of blacks to be like whites, but the education of whites to end racism. [Maybe in another thousand years.]

The students asked leading questions right out of the textbook, and he gently turned them aside to come back to the bedrock where there are no labels, no simple either/or answers, no symbols, nothing that can go on an exam paper, just the story. Any man’s story is, in part, every man’s story, someone once said.

Asked how he plans his novels he said this:

‘A disorderly writer like me is incapable of making plans and plots. He writes simply about people and the story begins with a phrase, an anecdote, or a gesture, and it goes from there and he tries to stop it as soon as he can. It’s not done with any plan or schedule of work. I write about man in his comic or tragic condition, in motion, to tell a story — give it some order and unity and coherence.

Or in reply to a question about the value of literature:

‘Poetry is best and first. The failed poet writes short stories. The failed short story writer has nothing left but the novel. Poetry condenses everything in a few lines, the short story in a few pages, the novel… goes on.

That old chestnut is tossed in, Where do you get your ideas from?

‘It starts with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does, and maybe even thinks, but he is in charge. I have little to do with it but edit it into some coherence to lay emphasis here and there, but the characters themselves, they do what they do, not me.

Leo Tolstoy said something like that in his time.

When I visited Rowanoak in Oxford Mississippi on stifling hot day one August I beheld his well-used typewriter and the walls on which he used to doodle with his characters. He did try to use the technique he had learned in Hollywood of storyboarding for some of his later novels.

My nomination for his most powerful novel? That is easy: ‘Abalsom, Absalom.’ His most accessible novel for a newcomer who has yet to enter Yoknapatawpha County is ‘Intruder in the Dust’ and his long short story ‘The Bear.’ The funniest is ‘The Reivers.’ The most exhausting? ‘As I Lay Dying.’ The most compelling? ‘Light in August.’ The most harrowing? ‘Sanctuary.’ The most penetrating? ‘Go down, Moses.’ Each of his titles has something distinctive while they form a whole. And let’s not forget that very short story, ‘A Rose of Emily.’ I was always sure it was ‘Emily’ for Emily Dickinson.

A word of warning. Faulkner only became Faulkner in Yoknapatawpha Country.

His earlier novels like ‘Pylon,’ ‘Mosquito,’ and even the elegiac ‘Soldier’s Pay’ are pre-Faulkner. I do believe I have read them all (some more than once) and most of the stories, too, that he managed to stop short before they, too, grew into novels.

On that pilgrimage to Oxford I also recalled that it was on the campus of the University of Mississippi that there were race riots in 1962 led by the governor of that state and subdued by Federal troops. This was a time when Faulkner could not show his face on campus, where now he is honoured.

Michael Gilbert, ‘The Etruscan Net’ (1969).

‘A very smooth and entertaining tale of adventure and intrigue in Florence shortly after the great flood. Art objects form the centre of the crookedness, and the social and political entanglements are done with a sure hand, together with a few persuasive characters. The suspense is light.’ From ‘A Catalogue of Crime’, eds. Jacques Barzun and Wendell Taylor.

Occasionally I select a title recommended by Jack and Wendy and this was one. It was readily available in 2004 reprint. Everything in the comments above is true. Alas, it is also true that I tired of it about half-way through. My failing, no doubt.

I liked the characters, the retired British naval man whose instincts help navigate the troubled waters, the indifferent victim, the forthright housemaid, Mercurio the odd ball adoptee, they all livened up the pages. The method of implicating the victim with his car was new to me. I also read with interest the soupçon of Etruscan art mentioned, and wished for more. How the Etruscans related to ancient Romans is one of those recurrent questions when I read about either, the more so having once seen some Etruscan ruins and art while resident in Firenze at the European Universities Institute. I also know that Decius never trusted any Etruscan, real or imagined. alive or dead.

But the plot quickly descended into yet another rendition of the total corruption of Italian society, from the building janitor, who for a few lira will let the Mafia killers into the apartment, to the traffic warden who for a few lira will wheel clamp any car, to the tax collector who for a few lira will raid the office and impound books….. no questions asked. Our heroes are up against a total conspiracy of a kind to make Stalin envious.

Yet somehow our heroes do prevail but by then I was turning the pages so fast that the detail of how escaped me. There were several villains involved and perhaps they came into collision for there is no honour among thieves, I suppose.

Lawyer by day and writer by night,

Lawyer by day and writer by night,

The author is very accomplished and industrious for there are many other titles. I might try one of the series because I like continuing characters.

‘Victor Hugo’s Conversations with the Spirit World: Literary Genius’s Hidden Life’ by John Chambers. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1998.

Eggheads! Did Victor Hugo (1802-1885) wrote ‘The Miserables’ on Guernsey in the Channel Islands? Yes, he did! He spent nearly twenty years in exile, three years on Jersey and most of the remainder on Guernsey. While this book is not a biography it does limn the relevant elements of this gargantuan writer’s gargantuan life. His books were big and so was he, and as big as he was his ego was even bigger. He regarded himself as the greatest writer ever, full stop, period, and end. He did not mean the greatest French writer, though he meant that, but the greatest writer of all, including William Shakespeare, who latter confirmed this judgement! (The best French writer had to be the best, because French was the best language per Hugo, though he had no knowledge of any other languages. It was a priori knowledge.)

No he was not a Mormon but yes the long-dead Shakespeare did concede Hugo’s surpassing genius … in a séance, for he sampled, practiced, and studied spiritualism with the same intensity he did everything else. At first he was disinterested in the many varieties of spiritualism that washed around Europe in the middle of the Nineteenth Century, but tolerated his wife’s interest, and then himself became hooked when it seemed that he could communicate with his dead daughter, the first born whom he loved (almost as much as himself, as one wit had it).

Some may remember ‘Bergerac.’

Some may remember ‘Bergerac.’

It was a time when the line between the living and the dead was a veil to some. Magnetism, mesmerism, table talking, automatic writing, rap rap, these were all in vogue. Once Hugo tasted this activity he drank deeply of it. A séance might start at 8 pm with a dozen participants in his Guernsey house and as the others departed or fell sleep in place, he continued on and on into the small hours of the morning.

And why not, he was H U G O after all and the spirits of the long dead crowded around to meet him! To the dead, he was a celebrity. [Pause.] Thus did Shakespeare rap out a message as did Aeschylus, Molière, Niccolò Machiavelli, and the Emperor Napoleon. Ego, indeed. He found further confirmation of his own self-estimate in these exercises, as if the chorus of praise from his contemporaries was not enough. Gargantuan that ego.

A séance.

A séance.

Hugo was not a Christian and yet he prayed. Hugo was not a socialist and yet he spoke for the dispossessed. Hugo was not a monarchist and yet he supported Louis Napoleon. Hugo was not a democrat but he came to oppose Louis Napoleon. Hugo loved Paris and yet lived in exile in the Channel Islands. Hugo was principled and yet he broke his word more than once. Hugo despised politics but twice served in parliament. Hugo made a point of defying classification with any one side or position. The words of Walt Whitman came to mind: ‘Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contract myself, I am large, I contain multitudes’ (‘Leaves of Grass,’ 1855). Hugo was a multitude.

Statue Hugo on the island.

Statue Hugo on the island.

Among the spirits who paid court to Hugo was Niccolò Machiavelli during a séance 16 December 1853 and on two other, later occasions (p. 224), and that is why I had look at the book. Most of the séances were recorded by a scribe as the spirits spelled out their messages a letter at a time, mostly in French, sometimes in Latin, and occasionally in an incomprehensible mishmash. While several participants including Hugo himself wrote up the experiences using the transcripts, most of the original transcripts have joined the spirit world, i.e., they have been lost. In this book we find that Machiavelli visited Hugo twice, the first two times they talked politics, and the last the subject was reincarnation and a summary of that last conversation is presented. Nothing further is said about the political discussions because these are among the lost transcripts. Given the Hugo was proscribed by Louis Napoleon III it is likely that Hugo denounced tyranny to Machiavelli, ah hem, in the transcriptions that survive Hugo does a lot of the talking, and so he probably did with Machiavelli who was probably left to agree as most people, living or dead, were in conversation with Le Grand Victor.

John Chambers

John Chambers

The book is well written and based on Hugo’s own accounts and those of contemporaries and it reads like a novel with asides for exposition. However, I had no interest in the word-by-word translations of the actual channeled material in the sessions which form the bulk of the book.

Marc Bloch, ‘Strange Defeat” (1944)

This is a personal memoir of a French officer who was on the front line in Flanders in 1940 during The Defeat. He was a supply officer who managed fuel for tanks, ambulances, motorcycles, cars, and trucks with Henri Giraud’s First Army. Bloch was a professor of history at the Sorbonne, and he volunteered to serve in 1939 again, having been an infantry captain in World War I. Some may recognise the name for Bloch was also a remarkable historian whose two volume study, ‘Feudal Society,’ is one of the most compelling works of history I have read.

Bloch wrote ‘Strange Defeat’ as a diary in the last months of 1940, and it remained unpublished at his death in 1944. He was in the Resistance, arrested by the Gestapo, tortured for information, and then murdered. None of this figures in his pages but it is a grim reminder of the mortal gravity of the place and time.

Bloch muses on his own reactions to the approach of war and his decision, at age fifty-two, to take up arms again and reflects on the men with whom he served, and analyses the Defeat from his captain’s eye-view.

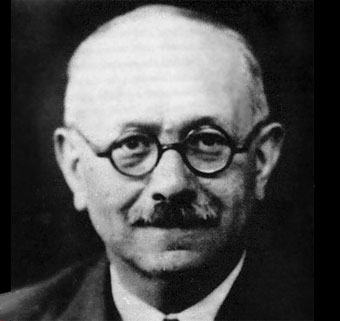

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

He emphasises that the military shibboleths of order and method could not bend but they could break. That is, there was little sense of urgency when the German attack began. He had fuel requisitions rejected because a corner of the page was torn or the ink had run, which meant a long drive back to complete a new copy and get it signed by field officers whose troops were engaged with the Germans, and then return along roads strafed by the Luftwaffe. None of these exigencies were sufficient to compromise protocol. There was all the time in the world, until time ran out and then panic set it.

Even when the First Army retreated, it did so at a leisurely pace, moving back twenty kilometres. His point is that the insistence on procedure and these short retreats were measured against trench warfare of World War I, not against the mobile warfare of the Panzers. A twenty-kilometres retreat was but less than an hour from the next tank attack, which was never enough time to re-set the line of defence. Yet French Army doctrine would not permit a longer retreat, and so nothing was available to facilitate it in the way of equipment, road signs, traffic controls, communication, identified positions, marked map coordinates, and expectation. (To retreat a longer distance required an order from Supreme Command and Supreme Command could only reached by courier and no courier could get through. Supreme Command refused radio and telephone communication even in distress.) The First Army then retreated in these bite-sized steps five or six times before it completely disintegrated. At each retreat more units lost contact, were cut-off by marauding Panzers, read the map sideways and wandered into a Belgian bog, or collapsed in exhaustion and fear.

Then there were the personal rivalries he saw in the career officers in the many headquarters where his duties took him. To say to one colonel that he had instruction from another colonel meant he would get no hearing at all, because these two colonels were old adversaries in the promotions list. After mentioning the first colonel’s name, Bloch watched helplessly as the second colonel dropped his requisition into a drawer and with an icy word dismissed him. Clearly that chit was going no further up the chain of command.

There are many other examples but perhaps enough has been said to make the point. The procedures were cumbersome, inviolable, mysterious, and most of all based on absolute obedience at the expense of any initiative. (By the way, German intelligence services were aware of French army procedures and took them into account in their own planning.)

Black was the day, but Bloch also met, worked with, and observed many officers who manfully did their duty despite the circumstances. More than one staff officer stayed at the radio or telephone directing retreating units to Dunkerque even as shell fire fell on them. Bloch is one of those thousands of men who spent days on the sands at Ostend as British troops were evacuated while the Luftwaffe strafed the beaches and artillery fire grew closer.

The miracle at Dunkirk

The miracle at Dunkirk

Along with more than 120,000+ other French soldiers he was himself evacuated. (Winston Churchill personally ordered the Royal Navy to make no distinction among Allied soldiers and to board them first-come, first-served. For a day or more before that order the Royal Navy had only taken Brits.)

Bloch landed in Dover, marched to the train station, stopping for tea and scones served to the group of French troops he was with at the local lawn bowls club, then onto a train to Plymouth where he boarded a ship for Bordeaux, and thirty-six hours later he was again in France. The French troops shipped back to French Atlantic ports like this were without weapons, some had lost clothing, particularly boots in the surf at Ostend-Dunkerque, some were wounded or injured, and devoid of any chain of command. Bloch and the compatriots he shipped with were billeted in a health camp near Bordeaux, where, he observes, they were received with far less warmth and civility than they had experienced in England where he and his fellows were heroes who had stemmed the tide of the Boches, but in Bordeaux they were burdensome failures.

In World War I the city of Bordeaux was a million kilometres from the front; not so in the mechanised age. No sooner did Bloch arrive than did the Germans. He became one of those poilus, dirty, dazed, ragged, head down, among a thousand others on a road, escorted by a lone Wehrmacht private with a single-shot carbine, marching into captivity.

Les poilus

Les poilus

At fifty-two the Germans deemed him too old for slave labour in the Reich and he was paroled to begin his career in the Resistance shortly thereafter.

A book to be read in parallel with ‘Flight to Arras’ from the pen of Antoine de Saint-Exupery, he of the ‘Little Prince.’ St.-Ex was an air force pilot who flew combat in 1940, then fled to Algeria to continue the war with the Free French. He, too, died in 1944 while on a mission.