‘What experience and history teach is this: That people and governments never have learned anything from history or acted on principles learned from it.’ Thus spake George Hegel in the ‘Lectures on the Philosophy of History.’

In contrast Ernest May explains the German victory ‘in terms applicable beyond its character or epoch’ as a parable for other times and other places. We can learn from history is the burden of this phrase. We can but do we.

This tome sets out to qualify, refute, and set aside the three most common interpretations of the Fall of France. Instead the Allies’ major error was to misunderstand German intentions, both politically and militarily.

These are the three common explanations of the German defeat of France.

1.That the Germans had a crushing superiority of men and material.

2.That the French and British were badly led.

3.The French people were morally lax.

Of course, there is some truth in each, which is why they have taken root, but May’s claim is that they are not decisive either alone or in combination. The Defeat was not a sure-thing, but rather a long shot with such a high risks that only a singular mad man like Hitler would do it. ‘Singular’ is not the right word. What I mean is that he alone decided, while in the Western countries there were many hands at work.

Against (1) the French and British had better weapons, e.g., French tanks, and more airplanes in the RAF. In addition, there was that large and well-equipped French Army. The German generals were dubious that they could match the Allies, and said so repeatedly to each other and to Hitler.

Against (2) there were many excellent leaders in a situation that defied rationality, i.e., Hitler wanted war and that was a fact Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier could not perceive, themselves horrified at the prospect of another war. The most significant leadership failure is probably Belgium’s King Leopold’s vacillation and that of his government. Certainly May does not gloss over this one. He also acknowledges that French generals (1) did not switch from peace time budget politics, crying poor, to war time reality easily and that there were political rivalries among them that were more important to some than the fighting and (2) the leisurely way communications were done by courier rather than telephone and the many levels orders had to go through to be issued and obeyed. These latter points were structural, it is true, but they were designed and implemented by the very French generals who later complained of these cumbersome structures, e.g. Gamelin. As to the former, May admits that Daladier had little hold on either cabinet or parliament and that Paul Reynaud’s decision to replace Gamelin in the midst of the battle with the seventy year old Weygand who had to fly to France from Syria was bound to fail. But Reynaud had to show the public he was acting. Well did he? Or would a stronger leader have weathered that expectation?

Against (3) the French had developed a resolve to resist by the time the Polish crisis occurred. Indeed the political leadership sensed this swing in public sentiment and that is what caused both the French and the British governments to go to war on the assumption that the public would not tolerate another compromise. Maybe but it is also true that there thirteen political parties, each jockeying of position, in the French parliament and they had a professional interest in disagreeing.

That there were doubts, fears, worries, hesitations among German generals is well known. Is not that always the case? Even the most bellicose general, when D-Day dawns has doubts, hesitations, delusions. Think of George McClellan’s fantasies about the grey hosts over the hill. Of Bernard Montgomery’s endless demands for more until he outnumbered the rump of the Afrika Corps 15 : 1 and then he still waited. Think of General Hermann von François waiting too long to execute his part of Schlieffen Plan. Think of General James Longstreet waiting for hours before ordering Pickett’s Charge. No general can ever had enough to be absolutely sure at any level of command. That the German victory was against the odds may well be true, but the qualms of generals is not proof of that contention. May seems to be insensitive to this general tendency.

And surely part of that demand for ever more material and men before committing to battle is done with one-eye on history. If made to fight now, and I lose, it is the politicians who are responsible for pushing me into the fight ill-prepared. If made to fight right now, and win, it is because I overcame the odds. Victory has a thousand fathers and defeat is an orphan. Many reports, appraisals, estimates are written for history to exculpate the writer, or to wring more funding from the niggardly political masters or both. ‘History memos,’ cynics call them. May seems insensitive to this common occurrence.

The divisions among the French cannot be papered over, though the author argues that there were periods, most of them of two or three years, when there were different alignments. Yes, and no. Yes there were accommodations but no, because many of the differences were deeply etched into history, regionalism, ideology, and religion. I am not convinced that there were significant changes. The social divisions in France were many and ran deep, and they certainly did not make France strong and imposing in Hitler’s perception. May seems to treat these divisions too lightly and to conclude that by September 1939 they had disappeared.

One of the things I do get from this book is that Hitler rose above the details of the arguments, how many airplanes, what range of flight, the number of bombs, the rate of production, the thickness of armour plating, the training time of pilots, and thousands of other technical details about training and equipment of all arms, and concentrated his assessments of France and England on the willpower of the elites to resist, to fight. While German officials and officers would cry poor because of the myriad of technical details involved, Hitler set little store by these facts. After an hour presentation on some such aspect of preparation by a general, he would wave it away with hand and talk about setting a date, next week, for the assault, leaving some general in stunned silence. The German generals delayed and argued for ever later dates. If left to their own devices, they would have been still planning the Western offensive in 1960. For them, planning, like management today, was an end in itself.

Also themselves deeply involved with technical details, Allied generals supposed that at some point German generals would talk Hiller out of a Western offensive, since on all the data the combination of France and England had the advantage, the more so adding Belgium and the Netherlands. Though Hitler saw this combination of allies as a weakness instead of a strength because the consultations would slow things down, the differing procedures would lead to confusion, the many heads involved would disagree, and there would be language barriers. He was right in all of these. May is silent on the fundamentals of Allied cooperation.

Instead of a direct attack on France the Allies anticipated an attack on Netherlands to get airbases on the English Channel, and perhaps on Belgium to close the port of Antwerp. Hitler played to that assumption with the first attack there, which proved to be a diversion, but it took far too long for that to be realised. That is, the French along with the British Expeditionary Force moved into Belgium to meet this attack and then got cut off by the main offensive in the south.

Added to that mindset the myriad of false alarms from November 1939 to May 1940, and the author does a good job of showing just how many false alarms there were, and how heavily qualified each was, along the lines of an ‘immediate attack will occur tomorrow, maybe, possibly, or not.’ He compares these occurrences to the warnings about Pearl Harbor to good effect. Some of these false alarms may have been planted by the Germans to weary, distract, confuse the Allies. It worked.

That Hitler did not attack the West immediately after Poland was at the time proof to many that the Germans were afraid of the might of the French army and the British airforce and would not attack later. This became another article of faith that led to the belief that an attack on the Netherlands and Belgium was most likely.

Meeting Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier face-to-face at Munich sealed the deal. Hitler saw no fight in either. At Munich Daladier said nothing, literally nothing. He was completely worn down by the back-biting and conflict within the French parliament and was counting the days until he would be displaced. (On Daladier, see the superb 2009 novel ‘The Ghost of Munich’ by Georges-Marc Benamou.) Benito Mussolini dominated the proceedings speaking a German no one could understand, but eschewing translators. That fog and mist suited Hitler for whom the meeting served other purposes (showing his generals he was willing to negotiate though he was not, buying time for preparations, courting world opinion, keeping the Soviet Union guessing, more closely involving Italy in his machinations, misleading all those who took him at his word, and, finally, assessing his opponents), the details were unimportant since he had no intention of sticking to any agreement. Chamberlain understood no German, no French, and no Italian.

We have that film of Chamberlain’s return from Munich with peace for our time, because Chamberlain mobilised the news media, including the BBC to record it. He made a point of mobilising and directing the media, says our author, far more than had been done previously by either Stanley Baldwin or Ramsay McDonald.

For their part it took Chamberlain and Daladier, and those around them, a long time to realise that Hitler really did want war. Many of them had been in the trenches themselves and they all knew others who had been and who had been maimed or killed. They could not conceive that anyone wanted to repeat that. It was only when it became numbingly apparent with the invasion of Poland that Hitler would not stop that they realised there was no point in further delay. The passing of time would favour Germany, as it added new territories and capacities, growing confidence, and allies, and the passing of time would see the British and French populations grew more and more fearful and demoralised. All that is the standard HSC interpretation from my years as an HSC examiner.

The French penchant for detailed planning meant everything was complicated. Because everything had been anticipated and planned, when a French unit came under fire there were pages of protocols to govern responses, and one has the impression that some officers were furiously leafing through the manuals to find the right protocol rather than directing their men.

The Belgians oscillated between clinging to neutrality and so denying cooperation with the Allies, or seeking Allied protection. Accordingly the move into Belgium when it was finally made, was too slow. Belgium also played a role earlier in stopping the extension of Maginot Line along its border. Belgium relied heavily on its own mini-Maginot Line in the impregnable Fort Eben-Emael near Liege, which was partly built by German contractors who turned over all the blueprints to the Wehrmacht, which meant the fort was put out of action by fifty men in a few minutes.

Eben-Emale was carved into this cliff face and dominated a river valley. There were many gun ports and block houses that do not show in this contemporary picture.

Eben-Emale was carved into this cliff face and dominated a river valley. There were many gun ports and block houses that do not show in this contemporary picture.

In building Eben-Emael successive Belgian government had declared it to be the essence of Belgian defence when it capitulated after one day, the psychological blow was decisive.

The Allies’ major strategic mistake was the belief that the Ardennes Forest was impassable to a large army, especially one with tanks and trucks. Even the evidence of eye witnesses did not overcome this conviction. It was fact-proof. Nothing would convince a distant senior officer that tanks and trucks were pouring out of the Ardennes even as they were pouring out.

The Belgian Ardennes

The Belgian Ardennes

But once the shooting started, the crucial tactical difference was that the Germans combined air and ground forces which the French did not do that for strategic reasons, and which the British did not do it for political reasons. The French air doctrine prohibited use of aircraft as air artillery! The cannons do that, period. The only tactical role of aircraft is to defend their airfields. The only strategic role is to bomb cities, which was ruled out at the time, not wishing to provoke the Germans into retaliating. The RAF wanted to keep all its aircraft to defend the homeland when the time came and flying low into columns of German armour would certainly mean heavy losses. Ergo when there were terrific traffic jams with thousands of German tanks and trunks on narrow roads, they were not bombed. Ergo when the French armies were pounded by the Luftwaffe as the Germans advanced, they had no air support of their own.

Moreover, neither the French nor British concentrated armour or motor transport, as the German did. That steel tip of the German offensive was irresistible, even though one-on-one French tanks were superior in armour and cannon. While the Allied tanks outnumbered the German ones, they were dispersed, so in combat the French tanks were usually outnumbered five to one. The French tanks were distributed one or two to a regiment of infantry as mobile block houses. Yet on paper there were more French and English tanks than German ones.

The analysis of intelligence is a crucial point. The French intelligence services gathered information and delivered it but did not analyse or evaluate it. A rumour would be dutifully reported, but its source would not be evaluated. A fact – the movement of troops – would be reported but not placed in the context of the reports of other troop movements. No one was responsible for putting all the pieces of information together. The several intelligence services did not want the responsibility and the general staff would have resented it had it been done. Ten reports of German troop movements would be filed but no one was responsible for reading the file and adding it up to ten. Each report was a discrete fact. The contrast was the Germans who integrated intelligence findings and analysed them thoroughly so that they knew how the French Army gave orders (in such detail that quick obedience was unlikely) and how the British gave orders (with so many qualifications and exceptions that quick obedience was unlikely).

Finally, at a tactical level both the French and British demanded absolute obedience, whereas the Wehrmacht doctrine stressed initiative and flexibility at the lowest levels of command, i.e., sergeants. In the confused situation that developed many a French command waited for orders that never came instead of acting independently.

One of the important points May offers is that most leaders (and their advisors) think the past predicts the future. To know what will happen tomorrow, look at yesterday. It does not always work that way. The linear projection of today on tomorrow can mislead as much as inform, if crucial information is ignored or changes are not perceived. Today is the best predictor of tomorrow, but only because nothing else is better, not because it is perfect. The hardest thing to do is to be open-minded about changes.

The many false alarms of a German attack on the West from October 1939 to May 1940 allowed German intelligence to monitor Allied reaction, and that fed back into the subsequent planning so that Fall Gelb evolved to the feint into the Netherlands and eastern Belgium to draw the most well trained and well equipped French armies along with the British Expeditionary Force into Belgium which would then be cut-off by the main attack through the Ardennes toward the sea and not toward Paris (which the French expected in a variation on the Schlieffen Plan of 1914). That the German attack on the Netherlands did not use tanks was attributed to the terrain, and not that the Germans were moving the tanks elsewhere to attack France, although there were many individual intelligence reports of such movements. The British feared German airbases in the Netherlands and wanted to respond with the drive into Belgium.

There were two political outcomes of the Fall of France.

First, Hitler believed his own genius was proven infallible and so did many of his generals, and those that did not, could no longer say so since Hitler had been vindicated by the achievement of a victory over mighty France. This combination of Hitler’s hubris and the generals’ reticence led to the gratuitous declaration of war against the United States and then the invasion of the Soviet Union and these led to downfall.

Second, the catastrophe frightened Britain into accepting the authority of government without the usual party and parliamentary bickering, back-biting, and undermining. It also put Winston Churchill into the big chair, and gave him a relatively free hand to select a cabinet, a war cabinet, and to appoint generals and admirals.

May argues that in the period from October 1939 to May 1940 French, and British, too, political leaders took positions and selected evidence to support them without regard to any overall appreciation of the realities. In both cases there was a reluctance to reveal one’s reasoning since that could then be challenged. Instead one just declared something to be the case, e.g., Swedish iron ore is decisive and if we can deny that to Germany the war is won. Rather than opening the subject up for debate to test its strength, it is closed. In the poisonous atmosphere of French politics exposing one’s reasoning would be have a suicide note and May does not credit that toxic atmosphere sufficiently.

Ernest May

Ernest May

The book is based on much original research and the results is a five-hundred page text with another hundred pages of notes and bibliography. The book takes its title from Marc Bloch’s moving little memoir ‘Strange Defeat’ (1944). On that more later.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘When the Bough Breaks’ (1985) by Jonathan Kellerman

The first in the series.

Alex Delaware is a psychologist who is gradually drawn into police work when a child abuser commits suicide in his office during the night. Delaware had been working with the victims of this perpetrator. That event jarred Delaware loose from his profession, his clients, his positions, his habits and much else. At the same time it also opened the door to helping the police with inquiries, in that quaint British expression.

In this case, a fellow psychologist has been murdered along with his girlfriend, and while Delaware did not know the man personally, there is a professional interest and then a police officer asks for his assistance in questioning a seven-year old child who is the only witness to event in an apartment complex in Los Angeles. ‘Questioning,’ as we learn, is not the right word, but rather finding out what the child, now very frightened, saw and then interpreting that. The child arouses his sympathies and he is hooked. If it sounds rather contrived, it is not in the reading.

I particularly liked his long interview with the curmudgeonly emeritus professor who enjoys dishing the dirt. If only…. The description of the rainstorm charged by lightning was very fine, though by then I was impatient to get to the point.

The killing of the dog was too much. Every woman Alex meets is attractive and attracted to him, but he manfully remains loyal to Robin. Tedious.

All of the pieces do fit together in the plot, though it is far-fetched, but then again maybe not. Reality is sometimes hard to believe, too.

There are thirty or so Alex Delaware krimies that I have never read, despite my taste for police procedurals. It came to mind when I recently heard a Garrison Keillor ‘The Writer’s Almanac’ podcast in which he mentioned Kellerman’s long road to publication. Ten years of typing away three hours a night in an unheated garage in New York and stacks of rejections before the first publication.

By the way, this is my third Kindle book reading.

‘The Wars of Spanish American Independence, 1809-1829’ (2013) by John Fletcher

Reading a biography of Símon Bolívar left me confused about events in Spanish America, and when Amazon’s Mechanical Turk recommended this title, I had a look and liked what I saw and sucked it down into the Kindle. Well worth the $1.12 price. This is a short guide book (just under 100 pages) that summaries the sprawling history of these rebellions, revolutions, and wars, the factions and forces involved, and the geography. The print version has coloured maps and graphics that do not show well on the Kindle but on the iPad they were superb.

Terminology first, I am tempted by habit to refer to Latin America but Fletcher makes it obvious even to the geographically challenged that Spanish America in 1809 extended to Oregon, including all the eventual United States states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and parts of others, as well as Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, St Domingo, and everything south to Tierra del Fuego with the exception of Brazil.

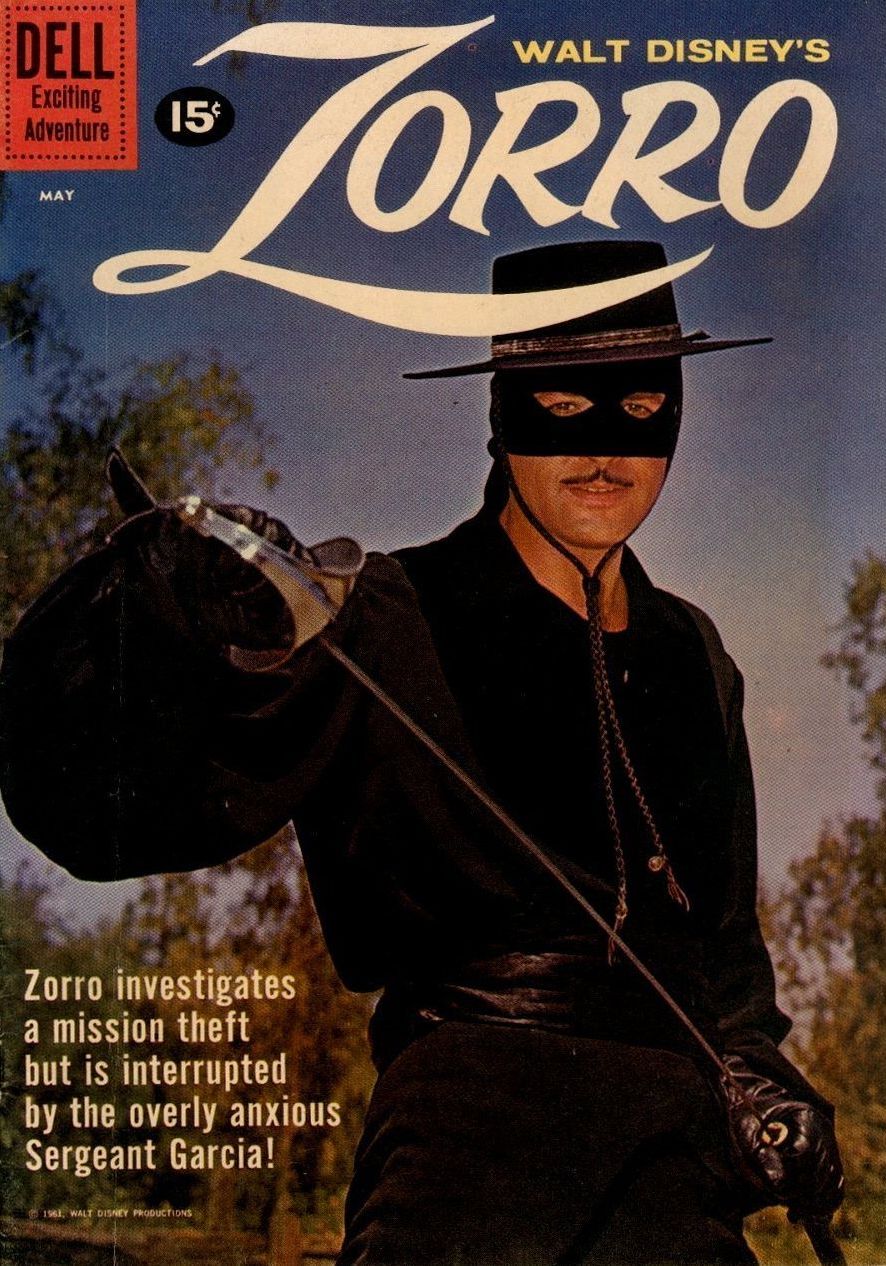

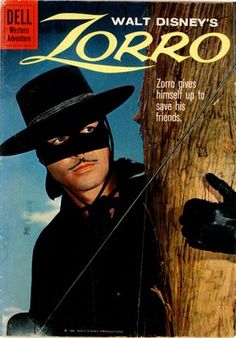

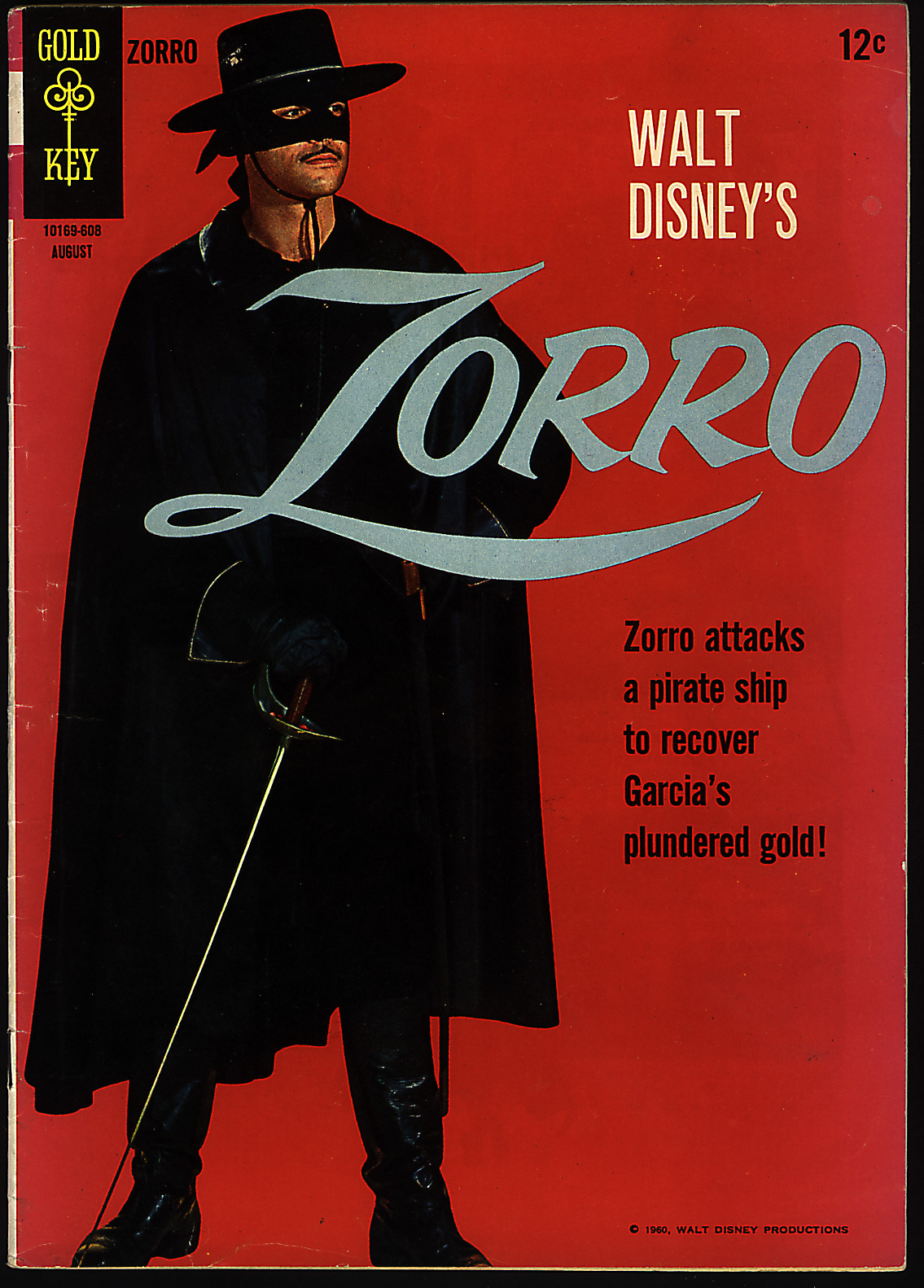

Second, it turns out I knew a little more than I thought, since I had watched Guy Williams (Zorro) fight the corrupt and incompetent Royalist regime in Old California while I was coming of age on the Rio Platte. Though Don Diego de la Vega is pretty vague about dates, it still turns on themes relevant to the 1809-1829 period. a distant colonial master, local villains, indians and blacks with no love for the regime. Locally-born Spanish Europeans taxed and abused by Spanish officials who steal all they can before returning to Iberia.

Third, I appreciated Fletcher’s deft summaries of the shifting divisions and alliances among both the Patriots and Royalists. Even those names are inadequate, but some labels are necessary. A score card is necessary to tell all the players, and at times they change uniform numbers, necessitating a revised score card. More on that below.

Among the American population were the three races and various combinations of them: Spanish, Indians, and blacks. When the shooting started the Spanish had been living in the Americas for nearly three hundred years. They were set in their ways. The Roman Catholic Church was a major factor. The Inquisition was hard at work in the New World.

Haiti loomed large in the minds of all Spanish, as it did in the southern United States into the 1860s. The slave revolt there confirmed the worse nightmare of many while confounding stereotypes. The blacks massacred their owners went the story, and took over, defeating two Napoleonic armies sent to teach them to respect the white man. Black slaves defeated two European armies!

There were divisions among the Royalists. Some wanted to continue the monarchy, but who was king, the old king clinging on, his usurping son, or Napoleon’s puppet. Moreover, some Royalists advocated a constitutional monarch and spoke less of a king and more of a constitution. In addition, in metropolitan Spain there were those who wanted no king of any kind, but did want to retain the empire. Each of these slivers of opinion was reflected in the Americas.

Among the Patriots were a host of differences as well. They called themselves ‘Patriots’ who were fighting for the freedom of their countries, and sometimes for their peoples, too. But which people? White, red, black, and the shades among them? The whites were further divided into those born in America, called Creoles, and those who moved there from the Old Country. Most of the blacks were slaves, but not all. The reds had tribal loyalties. Because of the methods of Spanish colonalism, the many colonies had almost nothing to do with each other. Lima was as foreign to Caracas as Madrid.

Most of the Patriots were loyal to their province with no larger conception of Spanish America. As soon as the Royalist were driven out the provinces would fall into conflict over rivers, boundaries, mines, and symbols. Sometimes they did not wait for the Royalists to be driven out before starting a war among themselves. A Columbian army would not go to Venezuela to fight the Royalists, nor would a Venezuelan one go to Columbia. And so on and on. If there is strength in unity this was one strength they did not have. Bolívar argued that if the Spanish retained one toehold in the Americas, then one day they would reassert their claims to the colonies.

Bolívar and José San Martin were among the few who saw a larger picture, the former for political purposes and the latter for military purposes. Though Bolívar had a political goal of a united Spanish American, he was not the accomplished soldier that San Martin was, but San Martin lacked Bolivar’s vision. Nor was there much chance they could work together. Bolívar was brassy, impetuous, egotistical, as well as determined, dogged, and tireless, while in contrast San Martin was reticent, careful, self-effacing, methodical, and slow (because it takes time to think), as well as a professional solider who was a strategist of note and a tactician of creativity.

Certainly a quarter, perhaps a half, of the populations (red, white, and black) in Spanish America died in this period. Many were killed after the battles, and others died of diseases loosened by the upheavals of warfare. Though Spain was feeble, on one occasion it managed to dispatch an army of 40,000 to the Americas to end the rebellions. Whole cities were murdered after battles to eradicate the enemy.

To get soldiers both sides courted the red and black races. The Spanish approach was to offer material reward, while the Patriots offered emancipation. The material reward of money would allow a slave to buy his freedom. The Royalists did recruit some individuals this way. Bolívar in contrast would declare emancipation and then recruit blacks to fight to retain this new freedom. The worked, too, on a larger scale. As a result slavery was outlawed a generation or two earlier there than in the United States. A parallel approach was taken by each side to recruiting indians. The Spanish offered individual incentives, Bolívar emancipation from forced labor and the so-called red taxes. Likewise the Patriots recruited soldiers from the captured Royalists with promises of citizenship.

In between the Royalists and Patriots were self-serving bands of armed men that preyed on both Patriots and Royalists or made temporary alliances with either to secure booty. More fearful than any of these bandits was the pestilence and disease let loose by the destruction of waterways, wells, damns, and the like.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars meant the world was awash with war surplus, and much of it went to these conflicts from northern California to southern Chilé. Likewise, there were demobilised soldiers who had no other life and who became mercenaries on one side or the other. Men who had fought each other at Waterloo ended up comrades in the European formations of San Martin’s army. Irish Catholics driven out of Ireland by Protestant England, found their way to Spanish America to serve with English veterans of Waterloo.

Brazil and Portugal also played roles in this story, trying to take advantage of the disruption among the Spanish to settle old grievances, appropriate land, secure river access, and the like. There were armed clashes between Brazilian forces and Patriots, Portuguese and Royalists, Brazilian and Royalists, Brazilian and Portuguese, and so on. All combinations.

No sooner had the Spanish given-up and left than the Patriots fell into prolonged conflict among themselves within cities and provinces and between provinces that became countries, some of the conflicts lasted until the 1860s. That goes some way to explaining the prominent role of the army in many Spanish American states. In contrast George Washington’s Continental army was under arms for eight years, but some of these Spanish American armies were at it for fifty years, e.g., in Argentina. Just as the Prussian army made Prussia, some of these armies could claim to have made the state.

As to the book, the organisation is coherent, the prose is crisp, and the pages are free from typos.

Fletcher is a UNL graduate and now a band manager.

Steed is dead. Long live Steed!

That is Major The Honourable John Wickham Gascoyne Beresford Steed, MC, OM, graduate of Eton (where he knew James Bond as the school bully), resident at 5 Westminster Mews. Further details may be found at his Wikipedia entry or in one of the biographies of this estimable but fictional English gentleman.

Steed, ready for action with bowler and brolley.

Steed, ready for action with bowler and brolley.

However gallant and distinguished Steed was to earn the MC and OM, he was nothing without Patrick Macnee (1922-2015). Gone recently to his reward.

Steed created the Avengers. The details are many but the nub is this. The original television series was a vehicle for Ian Hendry, called ‘Police Surgeon,’ with Steed as his assistant. When Hendry left to pursue other options, as they say in show biz, the producers gambled on Steed and reshaped the series. Therein lies an explanation for the title, ‘The Avengers,’ for the police surgeon sought vengeance for victims by identifying the villainy and the villain. I know when it was broadcast Stateside a different gloss was put on the title, what I have offered is the historical dimension.

In the 1962-1964 episodes Steed evolved into the bowler hat, the Saville Row suits, the bow tie or ascot, the umbrella, and the ever present smile. In the 1961 series he usually wore a shabby trench coat and a glum expression.

News of Macnee’s death prompted me to spin the old DVDs and watch the 1965-1968 episodes. There are many tribute web sites that say everything that needs to be said and which say quite a bit more than needs to be said. The later evolutions of the series I leave in silence, including even those that retained the services of Macnee.

We are at last catching up to the technology of the Avengers:

Pagers

Drones

3 D printing

Mobile telephones

TV remote controls

Self-driving cars

iPods

Web cams

Anti-gravity boots

Electronic IDs

The smart house

Satellite communication

Miniaturisation

But we still do not have Cybernauts.

More generally:

One episode concerned climate change,

another plant genetics

militant feminism

Ebola

student rebellion

Arab oil

Marvel comics

Each ‘ripped from today’s headlines,’ as the movie posters once proclaimed.

On a more personal note I learned from Steed that the glass is always half full, that a smart girlfriend is essential, that tying a bow tie is de rigueur, and a boutonniere is better than a medal. He was also known to drink rosé wine. I have tried to follow his example in all these ways and more.

The award for best victim goes to J. J. Hooter (‘How to Succeed at Murder’) with a close second to Ponsby Ponsby Hopkirk (‘Honey for the Prince’).

J. J.

J. J.

The unrivalled champion of villainy is Z. Z. von Schnerk (‘Epic’)!

Z. Z.

Z. Z.

Newtown Gym

I clocked up one hundred, that is, 1 0 0, visits to the Newtown Gym on my last annual membership. That has been a goal for years, but in the last five years I have only managed ninety plus visits on a membership. The Newtown Gym is upstairs over Civic Video and the ANZ Bank on King Street next to the old Post Office.

My annual membership pays for itself after fifty visits. Were I to pay the per visit fee on each session, at fifty the cost would equal an annual membership. Get it? In that sense all trips to the Gym after fifty are free. During the working years fifty was the goal.

The routine is to rise at 7:00 a.m. and we walk the dog around the Camperdown Park while drinking the coffee we get from Russell at the Varga Bar on the way to the Park.

The blurs are us moving along!

The blurs are us moving along!

Katie continues on home to the white orb – Majic’s bowl – to satisfy the inner puppy, while I peel off for the Newtown Gym two – four times a week. Après le Gym I return home for ablutions and eats. Doing it this way integrates the Gym into the day and gets it done. What doing it this way requires, is a conscious decision to dress for the Gym when we leave home. Morning appointments, mean I cannot go everyday. Phew!

The mural is visible from the weight room and the Upper Torso Trainers.

The mural is visible from the weight room and the Upper Torso Trainers.

Dressing for the Gym? In addition to the sweat pants and shirt, which sometimes do get sweaty, it means taking along a water bottle and some amusement, either a book (or Kindle) and the iPhone.

I do some stretches in the continuing effort to reduce infernal leg cramps to which I am liable and shift some medals to see if they are still heavy. They are.

I avoid Saturday mornings, leaving these to the taxlings who crowd the Newtown Gym. Sunday mornings are very quiet as they recover from Saturday night. It is the noise as much as the crowd on Saturday morning. The classes are conducted to noise, er, music, that is ear-splitting. Are all gym class instructors in the pay of hearing-aid manufacturers? They are certainly going to make themselves deaf, if no one else. The blast from this noise blankets the exercise bicycles in an auditory miasma that I avoid. Some of it even seeps into the weight room.

Being at the clichéd edge, I use a gym app to keep on track and keep motivated.

The day book. I used to get through four or five of these a year, now it is one or two.

The day book. I used to get through four or five of these a year, now it is one or two.

The gym app

The gym app

This gym app has proven more reliable and durable than the Jaw Bone Up I had or the Garmin I now wear as a watch.

In between bursts of high intensity training on the bicycles (upright and low by turns) or the Upper Torso Trainers, I listen to podcasts. The best companion is ‘In Our Time’ from BBC4 hosted by Lord Bragg. He is a consummate seminar leader, and each week he leads three experts through forty-five minute discussion on this or that pitched at a general audience. This is intellectual candy of a high order. The topics are many and varied from archeology, physics, life sciences, history, literature, and more. He does one a week for about thirty times in a year. A considerable backlog of podcasts is now available on the BBC4 web site and I have been selectively going through them.

Somehow he manages to get the experts to slow down, spell it out, cut the armour-plated qualifications, eliminate the incomprehensible technical details upon which their careers were made, and talk on a level that an interested auditor can follow, whether the subject is imaginary numbers, Etruscan pottery, the human gut, Byron’s ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgramage,’ stellar spectroscopy, or water molecules.

When his Lordship is not available, I turn to the daily ‘Writer’s Almanac’ with Garrison Keillor. More than once I have followed up one of Keillor’ s passing references, this podcast is short, to read John Hassler’s wonderful novels or to be stimulated anew by Emily Dickinson’s poetry.

And there is always ‘Lake Wobegon Days’ out there on the edge of the Prairies.

For those who must know everything, on days when I do not go to the Newtown Gym, I lift some hand weights on the balcony of the Ack-comedy and do some leg stretches there, watching the world go by, or watching the traffic jam back-up on Erskineville Road. There are some days when I do neither the Gym nor balcony routine.

Close readers, are there any other kind, will notice that is ‘annual membership’ and not a year of which I write. The membership is suspended when I travel. Last year that probably amounted to five weeks. Ergo the one hundred visits occurred over a period of fifty-seven weeks, not fifty-two. Surely that makes someone feel better.

‘Henry Wood Detective Agency’ (2013) by Brian Meeks

The first in a series of self-styled noir mysteries set in January 1951 in the Big Apple. A very easy read with many short chapters and some interesting characters, and then there is that closet which, like Henry, I thought was going to be explained and wasn’t. I kind of liked that. There was also plenty of woodworking.

It is at once very conventional and somewhat unconventional. The tough cop. The honourable criminal. The femmes fatales, who turn out to be OK. But mostly it is connect the dots. There are some bons mots but it does not crackle.

There is no tension and the characterisation is left to the woodwork. Too many chapters started with a new character who proved to be ephemeral anyway.

The rapprochement between the food critique who has an office nearby (and not at the newspaper for some reason) and the tough cop is not convincing, not interesting, and not relevant. They will probably appear in later titles in the series.

The mystery is that closet where occasionally Henry finds gifts from the future for both his hobby of woodworking and his job of detecting. That and Bobbie the motor-mouth estate agent who seems to know Henry’s business better than he should.

Brian D. Meeks

Brian D. Meeks

Left me unsure if I want to read another one in the series.

I read it as a Kindle book. My second.

‘Bolívar: American Liberator’ (2013) by Marie Arana.

What do Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Ecuador. and Bolivia have in common?

Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) was president of each, often simultaneously, sometimes in turn.

Bolívar cropped up in a book about Jeremy Bentham’s crusade to influence events in South America. Bentham corresponded with Bolivar, that is, inundated him with manuscripts, letters, books, telling him what to do. When I read that, I was remind of how little I know about Latin America, and reading a biography of The Liberator seemed a good place to start. Though truck with Bentham made me doubt Bolívar’s judgement.

The first thing to hit me was that when Bolívar was born, the Spanish, including his family, had been in Latin America and the Caribbean for more than 250 years. That is far longer than the European settlement in Australia today.

The first Spanish settlers came on the second and third visits of Columbus a few years after that first landfall on 1492. That was a long time for people to get set in their ways, for the population to grow, for the natural wealth to be plundered, for social structure to map onto the topography, for the bureaucracy of empire from Madrid to develop arthritis, for the local Spanish to resent and yet to defer to distant Madrid. And the distance was measured in months of sea travel which was both uncertain and made dangerous by weather, politics, and pirates of the Caribbean.

Bolívar was born in Caracas in what is now Venezuela to a Creole family of wealth and social distinction. ‘Creole’ in this case refers to those Spanish who were born in Latin America as distinct from ‘Peninsulares’ who were Spaniards born on the Iberian peninsula. This distinction had social, financial, and political dimensions. Peninsulares were of higher status because they were closer to Spain. They escaped many taxes that applied to Creoles. They held appointed offices under the crown denied to Creoles. At one time, such differences might have made sense and might not have been resented but they were unchanged for 250+ years and they chaffed. The more so because those Peninsulares who came were often adventurers, thieves, and incompetents, each bearing a royal license that put them above the law.

The native indian population had either fled the Spanish who remained on the coasts or succumbed to the European diseases that came with them. To labor in the silver and gold mines, and later to work the sugar canes fields, the Spanish imported slaves from West Africa on a large scale and had been doing so for generations when Bolívar was born. Thus were three races mixed and while the sclerotic civil law took little notice of racial distinctions, the Roman Catholic Church did in regulating marriage, registering births, and legitimating inheritances. Racial purity was also a priority to the Creoles in their status war with Peninsulares. There were many varieties of pardos and mulattos, those of mixed race.

Bolívar was widely travelled, through the United States recently after its War of Independence, France shortly after the Revolution, England where he met James Mill, Italy, Spain, and elsewhere. In Spain, such was his family wealth and social status, he sported with Prince Ferdinand who became king during some of the period that followed. He had a tutor who spoke but the rights of man and talked but Rousseau and that ilk. Though Bolívar had no education to speak of, his head was full of ideas in a time when anything seemed possible. Born to a rich family, he never had an occupation of any sort.

A conflict between the reigning Spanish king and his ambitious son, Ferdinand, divided loyalties in Spain. Napoleon entered and placed one of this flunkies on the throne. The several colonies in the New World were even more confused than their brother French colonial officials would be in 1940 with the competing Vichy and Free French governments. Spain had three kings, the old king, his upstart son, and Napoleon’s puppet. In addition there were two rival juntas that each proclaimed the end of the monarchy and the birth of a new Spain. None had much capacity to influence the New World, but its riches were certainly what prompted Napoleon’s intervention, which in turn prompted the Monroe Doctrine in a few years.

There were many reactions among the colonists along the South American coasts as the news made its way to them, reported in English newspapers on American or British ships, since they dominated the seas.

In this confusing time Bolívar wanted both independence from Spain and a social revolution, though I doubt he translated that into the loss of his own fortune, though he did lose it. He was one of the most belligerent of the Creoles, and as efforts at moderation failed, because such capacity as Spain could project was repressive – no negotiation, just mass hangings. Several treaties between local Spanish officials and obstreperous Creoles were violated within the hour of signature, like the treaties the United States made with indians.

One of many films featuring El Liberator

One of many films featuring El Liberator

I have no sense of Bolívar as a soldier. He had no training and his army was at most a few thousand. There are references to him training’s troops but I cannot guess in what he trained them. The terrain between the coastal colonies was forbidding, there being no roads, and simply moving a body of me from one to another was a feat of Hannibal.

He started with seventy men, surprised and routed a slightly larger Spanish garrison, and marched on with two-hundred men. By bluff and some confusion managed to cause another, larger Spanish contingent in a fortress to retire. Again he recruited more men, now at 500-hundred and marched on. This is another of his distinctions. He kept going. When other rebellious leaders scored a victory, they stopped. Not Bolívar. He was now about twenty-seven.

It is a long story with many failures, but Bolívar did not quit and in time learned from mistakes. The first lesson, was that it would be a long road.

Second, that the Latinos would have to do it for themselves. England would not intervene, though it would encourage from time to time to undermine its European enemies. The USA might be a model but it would not intervene either having neither the capacity nor will to do so.

Third, unity was the key to besting the imperialist, unity of the races, Creoles, pardos, mulattos, mestizos, blacks, and indians, and also geographic unity. He saw a single Latin American republic as the future. He opposed slavery and outlawed wherever he went which alienated the Creole slave-owning class of his origin.

Fourth, with a navy the Spanish could, at times, control the coasts, so better to operate from the interior.

Fifth, take allies where they can be found, and one place material support could be found was with the black regime in Haiti.

Sixth, compromise to amass a force. Do not insist on ideological purity from allies. Accept minimum cooperation if that is all there is.

Being a frail human being like all of us, El Liberator did not always follow these rules.

Since all the empires, French, Spanish, and English, constrained trade, the one place in the Southern Hemisphere where free trade was practiced was in Haiti. Several wealthy merchants from the United States had set up there to do business, and the offered funding, investing in future trading opportunities that would result if Spain was divested of its colonies.

Applying these lessons was not easy. Many fainthearted people wanted complete victory by the afternoon, or would quit. Others tried to woo England to no avail. The divisions among the Creoles and the ambiguous role of the Catholic Church, these alone would be enough to flummox most of us, let along crossing racial and geographic boundaries. There were no roads in the interior making movement nearly impossible. For some Creoles who had owned slaves, alliance with Haiti, a regime created when slaves massacred their owners, was impossible, even more impossible that freeing their own slaves.

That seeking of allies also came to mean trying to entice Spanish soldiers to switch sides with promises of citizenship and reward. His wars went on for more than twelve years as he criss-crossed the northern tier of South America in the belief that if the Spanish retained even one insignificant foothold, they would, sooner or later, return in force and subjugate the continent; it had to be a clean-sweep fore and aft. Alpine peaks in the Andes, swamps along the Orinoco, high deserts in Peru, jungle forests in Panama, endless plains, all these had to be traversed with his bedraggled followers. Nature and disease probably killed more than did the Spanish.

Bolivia, Ecuador, Panama, Columbia, Venezuela, and Peru, from these he drove the Spanish. The geography means nothing to me but on a map it is pretty impressive, putting George Washington’s campaigns into the shade.

There were constant conflicts among the locals, some remained loyal to Spain, but even among the anti-Spanish there were many deep divisions, social, racial, religious, regional, and political. Bolívar concluded that three hundred years of Spain’s authoritarian rule left the people incapable of ruling themselves. Though he adopted the forms of popular sovereignty, the governments, such as they were, he created were authoritarian, too. But he seldom stayed anywhere long enough to impose his will; he was always off to the next battle with another Spanish enclave. When he left, the government he had created fell to ruin and conflict.

His armies never exceeded 12,000 and were usually smaller than that. The wheel of death did not seem to phase him in the slightest. Over this period about half of the European population died. Add to that the deaths of blacks and reds and all the shades in between. Many deaths came from diseases for which we now have vaccinations, but even some them trace to the wars when water is contaminated, or populations re-located, or the dead are left unburied. Perhaps 50,000 soldiers died under his command. Of course, that is one battle for Napoleon.

Though the author describes many battles, it is all too much like a game. As far as I could tell Bolívar’s main tactic was to attack head-on. There is little indication he studied the terrain, disposed his forces according to it, tried to understand his opponents’ mind and play to a weakness, as did Robert Lee. Whatever tactical achievements there were, usually came from subordinates who also recruited soldiers of fortune from the demobilised armies of the Napoleonic wars with promises of citizen, land, and wealth. British and French veterans who had fought at Waterloo entered his European legion as comrades. He also bought much war surplus weaponry from Europe after 1815.

The author does a nice job of contrasting Bolívar with San Martin, though she is very clearly of the Bolívar camp. Think I will read about San Martin next to get the rest of the story. Over a 48-hour period they had three private meetings, alone. We know nothing of their discussions, though inferences have been made from the subsequent letters and memoirs of each. Nonetheless, the author writes of these interviews as though present. A license too far, I thought.

For ten years Bolívar fought the Spanish coloniser from Peru to Venezuela and back and forth. When the Spanish finally left, he spent the next ten years trying to hold together Greater Granada, as he called it, consisting of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. As soon as he left one province, as he styled them, the conflict would start. No longer having the Spanish to fight, they fought each other, across provincial, later national, borders, between cities, and within cities.

While El Liberator still lived, Peru had three presidents in one week, the first assassinated upon taking the oath of office, his successor two days later so that third took office on Friday. In combinations of twos and threes the states he created made war on each other and still do.

Once the Spanish oppressor was vanquished, many people saw in Bolívar a would-be king, tyrant, dictator… and opposed his every step. So blind was their automatic reaction — think Fox News here — that they even opposed his efforts to resign, seeing in it a devious tactic to win recall. That makes about as much sense as does Sarah Palin. This opposition continues with the entry in Wikipedia which asserts in its opening paragraph that his aim was to secure personal fiefdoms. No doubt it will be edited by next week.

He died at forty-seven, aged decades beyond the years by the exertions of the soldier’s life. The author estimates he travelled 75,000 miles, most of it on horse or foot in Latin America. At death he was penniless, and outcast by the very people whom he had liberated from Spain, dying in the care of a retired Spanish diplomat in a remote location in Colombia.

In death he has been a reliquary for Latino political leaders to bask in the glory of El Liberator, Simón Bolívar. Whenever a regime wobbles, its president-for-life unveils another statue of El Liberator, most notably and recently the late Hugo Chavez.

Chavez speaks

Chavez speaks

Though no one wanted him alive, Bolívar’s body has been dug up and divided among nations and moved several times, last by the aforementioned Chavez who also took his name for the country as the Bolivarian Socialist Republic of Venezuela. It seems there are no parks or plazas in the northern tier of Latin American without statue of El Liberator from Panama to Bolivia. It does not always work since Swiss hotels are fully occupied by such presidents-for-life.

I mentioned the egregious Jeremy Bentham above and also Montesquieu. One of the interesting themes in this story is whether the laws must be rooted in the society or must the laws be above and apart from the society, and this is a difference between Bentham for whom one-size, his, fits all and Montesquieu for whom the spirit of the laws is the spirit of the people. Intersecting with this argument is one about monarchy. Though Bolívar was unalterably opposed to monarchy, many of his allies and acolytes wanted to recruit a European prince to be king on the grounds that such an outsider, having no history and no loyalty to this faction, region, or race, could defend a constitution against the ebb and flow of local politics. It is an argument Georg Hegel made in his ‘Philosophy of Right’ (1821). That did not work well for Max in Mexico a generation later.

The last chapter is a superb summary of El Liberator’s life and career.

——————-

The book is based on extensive research and is written with panache, and of course, the basic story is both an epic in scale and a saga in duration. I read some of it with the Times of London Atlas open to the relevant page to follow some of the action since most of the place names meant nothing to me.

Marie Arana

Marie Arana

It is also true that the book lapses into hagiography too often for Saint Símon. It labels but does not explain, e.g., when others failed or quit Bolívar succeeded, why? Because he was charismatic comes the answer, which is no answer at all.

Some very strange word choice and some minor historical inaccuracy, e.g., there were no rifles and no artillery. The rifling of the barrels of weapons came later. There were muskets and cannons. It is quite a difference on each side of the barrel. When she writes of ‘riflemen,’ unless she specifically has Chuck Connors in mind, I think she means ‘infantry.’

Annoying overstatements, e,g,, these horsemen were the most audacious in the world. How does she know this. Was there a world horsemen audacity ranking agency?

At times the word choice made me wonder if the author, or translator, was a native English-speaker.

This is the first book I have read from beginning to end on a Kindle. It has taken getting used to, especially for notes and highlights and not losing my place. I started with turning off the public notes and highlights of other readers. No thanks. That is too much like reading a used book marked-up by previous readers. Bad enough reading some of the asinine reviews on Amazon.

Having carried about thirty kilograms of books on our European tour last year, I decided that I would not do that again. The only way to do that is to use a Kindle so I am practicing that before our next jaunt to Turkey in October.

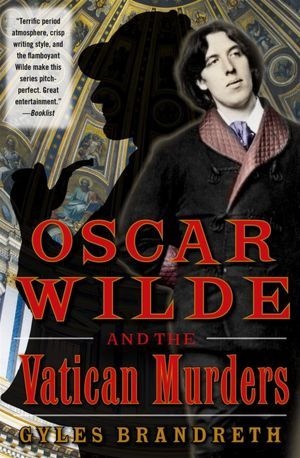

‘Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders’ (2012) by Gyles Brandreth

The fifth in the series and better than ever. Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle were friends, and the premise of this series is that Wilde is the model and inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, with his encyclopaedic knowledge, instant perception of facts, computer like processing of information, grasp of new languages in minutes, bolt holes here there and everywhere, mastery of disguise…

In this entry, Wilde and Doyle travel to Europe, each to escape his adoring fans, for some R and R. But no sooner do they check into a hotel than the game is afoot.

Doyle receives some strange mail, forwarded by his publisher, addressed to Sherlock Holmes. That has happened before, but not like this! Doyle shows and tells Wilde, and Oscar insists that they follow-up.

Toute Suite the trail leads to Rome and to the heart of Rome in the Vatican. Once in the eternal city, Doyle takes things as a they seem to be, but not Oscar who sees mystery and deceit in the very air. Some of the scenes occur under the dome of St. Peter in the dead of night.

Gyles Brandreth

Gyles Brandreth

The period details, the travelogue, the dialogues, but most of all the stolid Doyle as Waston to Wilde’s mercurial Holmes is a great fun.

Take one Greek crisis and add some Menckenium, then stand back!

Warning! Diatribe ahead.

Reading about the Greek fiscal crisis has been unavoidable, and I have also been reading a biography of H. L. Mencken. What a combination! Menckenium is a dangerous substance in the hands of an amateur like me. What would HL make of this? Polemic and invective, these were his fission and fusion.

He would excoriate all those saps who feel sorry for Greece, which, after all, sold government bonds with sovereign guarantees to European, American, and Australian banks. The money that the banks paid for those bonds went somewhere. Where did it go? Come back little Euros. Come out, come out, wherever you are!

Imagine the outcry at the time if those banks had refused to buy Greek government bonds on the grounds that it was not likely repay the money! Those now wrapped in Greek flags would have screamed for the banks to buy those bonds! Our sovereign guarantees are as good as anyone else’s! The isms would have filled the air: racism, nationalism, stupidism.

There would have been protests on Syntagma Square, demanding that the bonds be bought just like those of…., er, Portugal, Enron, Spain, and Italy.

Those around the world who now inflate their egos by feeling sorry for Greece instead of thinking, would have rallied to the Greek cause. So much for the pathetic claim that predatory lending was somehow at the root. When I read that I laughed louder than at Donald Trump, and that is saying something! (This man brings his own fright-whig. A trouper for sure.)

Who will buy Greek government bonds from now on? Hands up, all those ready to plonk down their life savings!

Then there is the perfectly idiotic claim that the money need not be paid, because after all the creditors are B A N K S.

People are important. Banks are not people. Greeks are people. Therefore Greeks win!

What kind of thinking is this? A kindergarten syllogism? My dog is capable of more complex reasoning than this.

As Angela Merkel has said many times the lending banks were investing pension funds in sovereign bonds, a conservative investment with a low rate of return but very secure; that’s why it is called sovereign debt. That is what most pension funds do, opt for high security at the price of a low rate of return.

Indeed, I have seen the point made in a German newspaper that one of the pension funds exposed to Greek debt has a great many retired Turkish immigrants on its books. It turns out Turks who have worked in Germany have no desire to write off Greek debts. So much for the supposition that banks are inhuman constructions of the aliens among us. (Their are aliens among us, to be sure, and they are hiding in plain sight on Fox News. Check out the mutant little fingers! [You either get it, or you don’t. Explanations are not included.])

Somewhere along the way I noticed the assertion that the Greek government could not repay the debt since Greek voters had voted against it. Talk about a stacked deck! If I could vote against paying the house mortgage, let me at that lever! Ooops, too late, already repaid with interest. I will side with Aristotle on this one, when he says in ‘The Politics’ that a new regime had best honour the debts of the old regime.

Then there are arguments from authority. An old favourite in the classroom. ‘A Nobel Prize winning economist says thus and so….’ and that must be the final word. Hmm. This particular Nobel winner has a track record of one blunder after another since the Prize went to his mouth. He is displacing Linus Pauling’s long-standing record for the most embarrassing gaffes by a Nobel Prize winner.

Finally, the very first claim the Greeks made, which is still coded in the reactions, is that Germans are all Nazis and to hell with them! Nothing Germans say is reported on the BBC or the ABC websites. Facts are unnecessary when reactions are so ready. ‘They can afford to pay, so let them pay.’ Really? This is too imbecilic to merit a response. Well, maybe a little response: that many of the purchases of bonds were laid off to other banks in the United States, Latin America, and yes, even distant Australia. Those who want higher mortgage rates, put those hands up now!

Greek-debt deniers line-up with climate-change deniers, Catholic Church pedophile deniers, Aboriginal-slavey deniers, Holocaust deniers, Shakespeare-wrote-it deniers, Moon-landing deniers, Flat Earthers, and the aliens-did-it mobs.

Where will this all end. I dunno. But I do know that Italy, Spain, and Portugal are waiting in the wings. Any concession Greece gets, they, too, will want it. Retrospective is OK!

Meanwhile, Great Britain has learned for another generation or two the importance of staying out of the Euro(pe).

Full circle comes around to the question of where all those Euros went in the first place. No one seems to be interested in pursuing this matter. I do hope some of them were salted away in Cyprus! Where…’hocus-pocus’ they disappeared when the Russian mafia occupied the island without firing a shot.

Reducing complex matters to simple slogans, and demonizing others, that is civilised debate as we know it.

To the H. L. Mencken in me, this is all a laughing matter, like religion, democracy, and the ABC’s self-righteous efforts at news-reporting, but the last time a Greek government had a financial crisis of its own making, in order to distract attention from that, it started a war with Turkey in Cyprus.

The rowdy scenes in parliament in Athens and the endless protests in Syntagma Square, makes me wonder what the generals are thinking. They are all Maoists at heart: order grows out of the barrel of a gun, said the Great Helmsman, while slaying his countrymen by the millions and becoming a hero to the brain-dead in the West.

I hesitated to write this because I supposed I would earn a torrent of abuse from those rushing for a selfie atop the virtual barricades, but then I realised, none of these people would bother to read it anyway. Just to make sure they did not read it, I did not include any graphics. Why write it then? All bloggers know the answer to that: Because it is there.

Wait! The Oracle speaks! Those who react to my diatribe will:

1.Accuse me of committing the same errors I input to others. This is SAP (Standard Arguing Procedure) practiced by…saps, of course.

2.A second ploy will be to reach some one technical aspects among the myriad and assert this undermines the argument.

3.A variant of two above is to find a typo and claim that it means the whole work is useless. I always include a few typos to draw off these microbes.

4.Of course, all the existing justifications can also have an encore, starting with various false historical analogies only vaguely understood by those looking for support for a position already determined.

‘The Dog/The Cat’ at the Belvoir Theatre

It is not often that I hear my own department at the University of Sydney mentioned on stage, but it is in this production.

We entered committed to dogs in the eternal world war between the canine and feline, at the end we had to admit that the cat stole the show.

But as any dog will say, the problem with the first part of the title above is that there was NO dog. What is a dog to do if it is not there? That sounds like a Zen question. Moving on.

The staging was exhilarating. The players were exuberant and mournful by turns as we charted the ups and downs of the love lives of the principals.

It is sold out for the remainder of this season but there is a waiting list for cancellations. That might be worth a try.

I booked long ago after reading a review, but when Herself asked me on the night why I had wanted to go I had forgotten the substance of the review. It didn’t matter. The show sold itself. No mediation required.