An early entry in the long running series of the cases of sergeants Ernie Bascom and George Sueño, two investigators in the United States 8th Army in South Korea in the middle 1970s. The Cold War is intense and no where more intense than along the Military Demarcation Line within the Demilitarized Zone. South Korea has a military government that justifies its crimes as necessary for security. American conscripts discover that money can be made in the black market, selling U.S. army equipment and supplies to Koreans. There is plenty to go around, unless someone gets greedy. Well, yes, that does happen.

The time and place are richly detailed. including the ways of Korean National Police and the interstices of the U.S. Army. The 8th Army wants no trouble, preferring to ignore corruption and even murder within its ranks rather than face bad publicity. The investigation of the death PFC Marvin Druwood was superficial and the subsequent disappearance of MP Jill Matthewson is even less thorough. No sooner is the carpet replaced on these two events, then Bascom and Sueño arrive.

Jill’s mother had written to her congressman who in turn has insisted on answers. To go through the motions Bascon and Sueño are sent to the Second Division near the DMZ with a very limited remit. The Second is a field unit while our protagonists are Rear Echelon M…. F…..s; they are not welcome and the veneer of cooperation drops quickly. No one is happy about the assignment. But of course, once engaged Bascom and Sueño just will not let go.

Bascom is the action man. Show him a door and he kicks it in. A roomful of thugs delights him and only Sueño can hold him back, most of the time. Volatile! He has a self-destructive fearlessness that frightens Sueño at times. For his part Sueño is the strong silent type who spends all his spare time learning the Korean language and culture. Life is a puzzle to him and tries to figure it out. Bascom is on a one-way ticket and determined to enjoy the ride, while Sueño cannot quit an unfinished job. Bascom is often impatient with Sueño’s efforts to figure things out, and he neither understands nor cares about the explanations Sueño produces.

They are both cast-iron in these pages. They drink enough alcohol to kill a normal man and seldom sleep more than four (4) hours a night on the case, while travelling the length and breadth of South Korea in an open jeep in the winter! After several beatings, it takes each of then a few pages to recover. Ironmen, indeed.

Limón draws his Korean characters with respect, none are plot devices. The prostitutes are business girls, proprietors of their own small business. The bars and brothels supply the American demand which has created much that is ugly in Korea, but nonetheless the Northern threat is very real. There are martinets among the army men they encounter but there are also some very wise owls who have survived a long time in troubled waters from whom a nod or a hint goes a long way. Sueño has learned to read these signs, which largely escape Bascom.

Martin Limón, whose affection for Korea shines through.

Martin Limón, whose affection for Korea shines through.

The books are more violent than my usual fare but the compensations are in the travelogue and the puzzles in the plot. In this title I also warmed to the idea that the ultimate prize was a celadon crane vase, perhaps like some we saw at the national museum in Seoul in 2004, and not money or drugs. I do find Bascom’s hormones repetitive.

In a world of misnomers, the Demilitarised Zone must take some prize. It is completely militarised. I visited the DMZ twice in 2004 and found it scary. A million or more men armed to teeth are each side of a line down the middle of a meandering river. Yikes!

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘The Case of the Love Commandos’ (2013) by Tarquin Hall

Vish Puri, India’s greatest private eye, as he finds occasion to remark several times in these pages, is on the case with his redoubtable team: Doorstop, Facecream, Tubelight, and Grunt. With such an ensemble cast, what could go wrong? There is a lot of trip and some arrival, too. The trip includes a selection of Indian cuisine became Puri is always hungry, and always eating. The back-matter of the book includes several recipes and a glossary of Indian terms, many of them are food.

In addition to Puri’s team of operatives there is his arch rival Hari Kumar and Mummy, Puri’s inquisitive. intrepid, and tenacious mother-in-law. And then there are the Love Commandos.

When Romeo met Juliet neither set of parents was happy and between the loving couple placed many barriers, yes? We all know how that story came to a sad end. They needed the Love Commandos to extract them from their parental restraints and spirit them away to a new life together. In an India with arranged marriages there are many Romeos and Juliets and the Love Commandos fill a market niche by offering elopement services for just such couples.

Puri is a traditionalist in every way including arranged marriage which has worked out fine for him. But his number one operative, Facecream, it turns out, moonlights as a Love Commando. Disapprove though he might, she has always been a loyal and adept agent and he can only return her loyalty by assisting in one of her commando operations when it turns bad.

From Dehli to Lucknow with a side trip to Agra, the adventure unfolds, while Puri eats his way through some of the regional cuisines of India but one step ahead of his rival Hari Kumar, who for reasons to be revealed later, seems to be working the same case. Corrupt politicians, unscrupulous Swedish medical researchers, retired Gurkhas hired out as muscle, an unholy holy man, some miserable Dalits (Untouchables) are among the parade of characters.

Tarquin Hall

Tarquin Hall

The touch is light and the book is replete with slices of India but the plot is deadly serious.

I have read two earlier titles in this series with equal amusement and enlightenment.

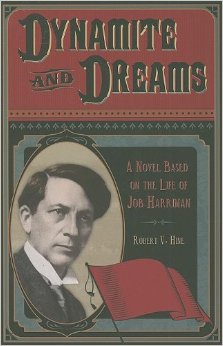

‘Dynamite and Dreams’ (2008) by Robert V. Hine

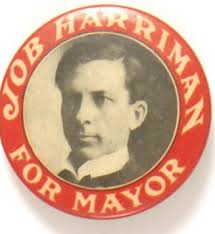

This novel is derived from the the life of Job Harriman (1861-1925) an American socialist leader. He was Eugene V. Debs’s running mate in the 1900 presidential election. He also contested the mayoralty elections in Los Angeles twice prior to the Great War.

1911 campaign button

1911 campaign button

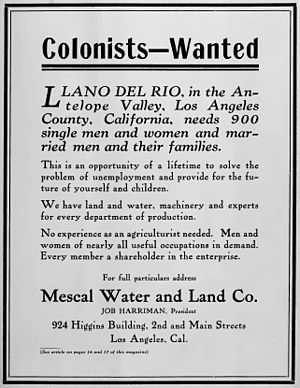

Though afflicted by tuberculous he campaigned with a fierce determination. Giving up on politics later, he led a band of true believers into the Mojave Desert east of Los Angeles to carve out a city on the hill at Llano. That effort failed and a splitter group followed this Messiah to the wilderness of Louisiana to New Llano in the pine forests on the Texas border.

The Los Angeles elections were brutal, marked by street fighting and bombs. Harriman was born to the priesthood, and campaigning gave him a chance to preach which he did with vigour and vehemence. Those who were trying to establish labor unions saw socialist politics as a distraction or worse. Then there were the Wobblies who had no use for union incrementalism or socialist election campaigns. All three of these elements were well represented in Los Angeles before World War I. Ranged against them were the plutocrats and robber merchants of the era along with the railroad magnets, who were the worst of a bad lot. In between these zealots, as always were the decent majority.

In the novel Harriman (in these pages styled Bannerman, for some reason) campaigns diligently for the Debs ticket in 1900. ‘Based on a true story,’ as they say in Hollywood, because Harriman did not campaign at all. Harriman could barely abide being in the same room with Debs (who was a union man first and last) and Harriman went to a conference in Europe to talk about socialism during the entire campaign. Because of his origins and commitment to labor unions, the hope was that Debs would unite the factions but he was reviled by the holier-than-thou socialists like Harriman and despised by the Wobbles. Harriman was on the ticket not to help Debs campaign but to hold a place for a real socialist.

The ‘dynamite’ in the title has two meanings. The first is Harriman at the pulpit; he was a dynamite speaker. The second, literal meaning, refers to the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. The owners blamed the socialists, labor unions, and Wobblies without bothering with the minute distinctions among them that so pre-occupied them. The socialists and labor unionists said that the owners had blown it up to put the blame on them. The Wobblies wished they had bombed it. If all this starts to sound like the Reichstag fire in 1933, there are parallels. No doubt some among the plutocrats would have been capable of such a deed, but they did not have to do it.

Clarence Darrow led the defence for the two brothers accused of the bombing, and Harriman worked with him. But the bombers confessed, having killed twenty-one (21) workers and injuring a hundred more, it hardly seemed a blow for the cause. The novel slides over the top of these facts, as it does many others. Bannerman-Harriman convinces himself, perhaps thanks to a feverish dream caused by his tuberculous, that the bombing and subsequent trial represented some kind of victory for socialism.

The move to Llano proved difficult in every respect.

Recruiting advertisement

Recruiting advertisement

The one thing that money cannot buy in Southern California is…water. The Mojave desert, home to Joshua trees, is called a ‘desert’ for a very good reason.

Joshua Tree

Joshua Tree

Llano was on the edge of the Mojave and water was scarce. The United States Weather Service says the average daily temperature at Llano ranges from 37C to 41C over a year. Whew! Booming Los Angeles soaked up all the water there was. See ‘Chinatown’ (1974) for a reminder. Long after Harriman and his band of believers left the area, Aldous Huxley spent some time nearby using peyote and, he said, starting to write ‘Brave New World’ in that drug-induced state.

Ruins at Llano.

Ruins at Llano.

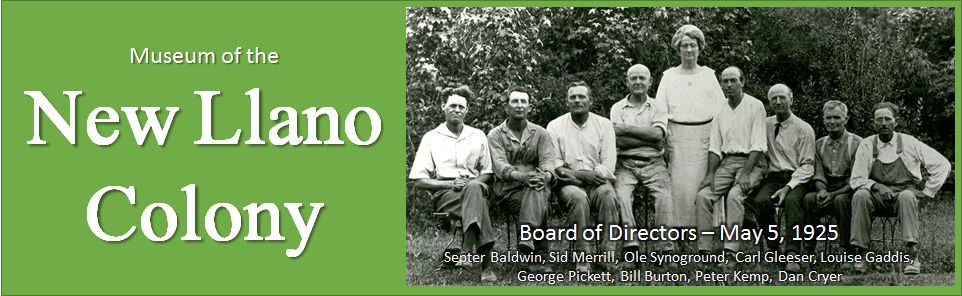

A hard core followed the prophet Harriman to the pine forests of northwest Louisiana near Leesville and founded New Llano which eked out an existence for a few more years in a sawmill operation. It demonstrated admirable pragmatism in finding means to sustain itself, unlike many other intentional communities. The economic boom of World War I made the mill profitable, while those in New Llano denounced the war as a plutocrats’ war and avoided the draft with ingenuity. In both Llano and New Llano Harriman was something of a tyrant imposing his will on one and all, when he had the strength to do so, but that is omitted from this story. One of the reason Llano fractured was because, as one participant said, they had but exchanged one boss for another. By the way, Job Harriman was no relation to Averell Harriman (1891-1986) of New York.

From Museum of West Louisiana

From Museum of West Louisiana

The Los Angeles Times had sworn a vendetta against Harriman, it seems, and it maintained the rage with repeated press attacks on him while he was in Llano, and even when he moved to Louisiana it did not relent. The attacks were as creative and truthful as Fox News. The Llano colony lasted three years and New Llano another seven years. In the annals of such intentional communities ten years is a good run.

Robert Hine

Robert Hine

California historian Robert Hine turned his hand to novels, this being the second. It is all rather didactic and the characters are all surface.

‘John Stuart Mill: A Biography’ by Nicholas Capaldi (2004)

This book is an intellectual biography of that singular individual John Stuart Mill, son of James Mill and husband of Harriet Taylor, these two being the most important facts in his life. Hereinafter James Mill will be referred to as James Mill and John Stuart Mill as Mill. Got it?

James Mill’s father, Mill’s grandfather, was a shoemaker in Scotland. James Mill was a bright lad and earned scholarship to finish a basic education and became ever after an autodidactic. The family was and remained irreligious and that barred James Mill and Mill from the clergy, the most learned of professions, as well as from the law and parliament, and also universities. A lawyer, a parliamentarian, and a university don, each had to accept publicly the thirty-nine orders of the Anglican Church and neither James Mill nor, later, Mill would do so in contravention of their own beliefs. For someone with intellectual interest and ambitions there was little other opportunity, but to work as a clerk. Since Ebenezer Scrooge was not hiring, James Mill found his way to the East India Company, which was a private corporation and did not require allegiance to the established Church.

James Mill

James Mill

James Mill was a hyper-Calvinist in everything but theology. He was exacting and critical. He prospered at work, and educated all of nine children at home. His education of Mill at home is well known. It started at about age 3 by which time young Mill was reading Plato’s dialogues. It was a massive and unremitting program of force-feeding. Mill in turn was made to teach his siblings. The children seldom left the house and none had any friends. Mill does not mention his mother even once in his ‘Autobiography’ and James Mill treated her like a servant, said those who visited the house.

Mill was a child prodigy and completely inept social and physically. He had no friends and never played any games that boys played and so his motor skills were limited to shoe tying. The same is true of the other children but Mill is the focus here.

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

James Mill was an acolyte of Jeremy Bentham and together they sired utilitarianism as a social and moral school of thought. Bentham became a de facto godfather to Mill who in turn was the godfather of Bertrand Russell. Bentham discretely supported James Mill’s family, having made a pile of money by investing in a mill in Scotland. The milll was at New Lanark and run by Robert Owen, himself a social reformer of note.

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

Bentham had a joie de vivre that James Mill lacked and Bentham in time revealed to young Mill something of the wider world of poetry, drama, literature, and walks in nature, and a visit to France which made the young Mill a Francophile. James Mill deferred to Bentham’s influence on his son, Mill, but turned each new interest into another assignment. A walk became an exercise in collecting, identifying, researching, and preserving botany samples. The visit to France with Bentham required Mill to learn French. To read Shakespeare became and exercise in the history of the English monarchy. James Mill drew a line at Shakespeare’s history plays. These Mill could read but not the tragedies or comedies. They might be a bad influence. See Plato on the dangers of poetry. James Mill made Mr. Gradgrind look like light relief. See Charles Dickens’s ‘Hard Times.’

I have long thought that Mill had the education of a Platonic philosopher-king. At first he learned by rote and repetition, seldom understanding what he read. His father was impossible to please and the slightest hesitation, not to say error, would mean the whole lesson had to be repeated from the beginning. Mill feared his father’s judgement. (Yes, James Mill was feared rather than loved but not hated.) One lifelong friend of James Mill said that he, James Mill, never praised anyone and criticised everyone immediately and often. When Mill taught his younger siblings, if one of them made a mistake, James Mill required Mill to repeated the lesson until all eight children were letter perfect. Their home schooling started each of seven days at 5 am and continued to 9 pm. James Mill conducted the hours 5am to 9 am and then went to work at the India House, returning for the testing session from 6pm-9pm. From 9 am to 6 pm Mill schooled his siblings. Such reinforcement as James Mill offered was always negative, though never corporeal.

James Mill educated his children at home because school education was too shallow and sloppy. His children seldom left the house. Likewise he saw no need for any of his children to go to a university. He particularly concentrated on Mill to make him the perfect and complete exposition of utilitarianism. James Mill created Mill so that he could go forth and reform the world in the image of Jeremy Bentham. Mill was an android artificially made for a mission. Indeed some of Mill’s peers in later life referred to him as the mechanical man. Mill’s upbringing differed from Plato’s philosopher-kings who were reared with others destined to be guardians and auxiliaries and even when crowned they did have annual sexual relations and common families, but Mill did not have any of that. They had social and sex lives, albeit constrained, that he did not have. A single purpose android is a more accurate description, like Mr Data without the tap dancing.

The software in the android became corrupted and Mill had a nervous breakdown when he was twenty (20). In his ‘Autobiography’ Mill blames this breakdown on the strain of his intellectual work. Capaldi, like just about everyone else, sees in it a suppressed rebellion against his domineering father. Mill did gradually recover his health and continued publicly to support his father in every way, but he began at this time to think for himself and gradually to step out of his father’s shadow in the safety of his own mind. After his father’s death Mill began to change utilitarianism, adopt liberalism, court Harriet, and more.

Harriet Taylor

Harriet Taylor

Mill’s long courtship of Harriet is well known. It was contentious and scandalous at the time. She was a married woman, and yet they were seen everywhere together, she clinging to his arm and he deferring to her, including at least one unchaperoned trip to France. Mr. Taylor was none too pleased about any of this. Given Mill’s repressed nature it is unlikely that Mill and Harriet had sexual relations, but by the standards of the day, that hardly mattered. He thought the world of her and extolled her qualities far beyond the mere mortal. When Taylor died that freed Harriet, divorce having been out of the question, the appearance of adultery was preferable, it seems.

They married almost immediately after Taylor’s death and had about ten years before she died. I had not realised it, but the three most famous of his works came after her death: ‘Utilitarianism,’ ‘On Liberty,’ and ‘Considerations on Representative Government.’ Mill thought of these essays as memorials to her. In all of these three, along with his earlier work, the underlying and unifying theme is autonomy, defined as the capacity, the ability, and the responsibility to decide for oneself. Achieving that was a moral goal for individuals and a determinant for public policy to create the conditions for individuals to develop the ability and capacity for autonomy through education, example, discipline, exposure, personal growth, and surrender to the larger whole. Insofar as democratic political institution encouraged and promoted autonomy he supported them though he had learned from Tocqueville to fear the tyranny of the majority (for a current example, watch 7MATE for one whole day).

Autonomy is not license or freedom, nor even liberty. Think of an orchestra. Now take away the conductor, the first violin and any other authority or leader. If the musicians are autonomous their own comprehension of the the needs of a given piece of music will lead them to participate, or sit it out, and to do it a certain way that blends them together into a whole. a if they had a conductor. If and when that happens, that is autonomy. By the way, there are leaderless orchestras that do not descend into the conflagration of the Fellini’s ‘Orchestra Rehearsal’ (1978). Another example that came to mind is the Gospel of Mathew that calls upon believers to decide for themselves, and in so doing their decision will coincide with the divine. Emmanuel Kant makes a powerful example from that gospel by urging the devout believer even to turn away from a risen Christ, and decide… In the telling most of the power is lost; read it in Kant.

He also served one term in parliament where he was a formidable committee man, I believe, but none of his committee work is mentioned in these pages. I have read Hansard micro-cards that record of some of his testimony to parliamentary committees and interventions while on committees and found them to be trenchant. What I saw related to the Northcote and Trevelyan reforms of the civil service. In his parliamentary career Mill was usually on the side of the angels but not always. He argued and voted for the death penalty for murders.

Capaldi does a superb job analysing Mill’s many, many texts and shows Mill to be a far more complex thinker than revealed by the simple elegance of his own prose. Capaldi brings out well the the French and German influences on Mill. For the French there is Tocqueville, of course, but also Saint-Simon fils and Auguste Comte. For the Germans the romantic poets and even that dynamic duo of Kant and Hegel. In all, Capaldi goes a long way to establishing Mill as a figure who cannot be typecast. Was he a conservative? a liberal? a radical? a democrat? an elitist? a deontologist? a utilitarian? a positivist? an empiricist? The answer in each case is ‘yes’ but in his own special way. He was both a liberal and a conservative.

Mill had form. He was arrested for obscenity while a teenager. The crime, of which he was certainly guilty, was passing out pamphlets urging birth control.

Mill was a lifelong proponent of female suffrage. When he and Harriet married, they went to some pains to avoid the norm according to which he would have become the owner of all of her goods, including a considerable inheritance from Taylor.

Mill’s book ‘A System of Logic’ made his name in the first instance. It was so highly regarded that in addition to large sales, almost immediately, it also went on the curriculum at Oxford and Cambridge. In short order, his other books began to follow on to the curriculum, including ‘On Liberty’ and ‘Representative Government’ and they in turn could be best understand by reference to the previous thinkers he analysed and synthesised and so was born ‘Political Theory’ as a field of study in universities. Indeed his impact on the Oxbridge universities, where he never set foot, was so great that after his death, academic reputations were made by tarnishing his; the attack of the pygmies on the defenceless is always a sure sign of stature.

Because of the range of Mill’s works, after his death he was claimed as a precursor by a wide variety of causes from co-operatives, Fabian socialism, and the 800 Club. To his contemporaries Mill was an enigma: he did not fit into any of the categories available, and they knew it. It is still true that he is an odd man out but we generally no longer recognise that, and force him into one box or another, and then dismiss him. Our loss. Today he has largely been reduced to a stereotype no less distorted than that which applies to Machiavelli.

I would have liked a more clearly presented chronology, maybe as an appendix. I also found it hard to read, especially the extensive quotations from secondary sources and Mill’s own ‘Autobiography’ which interrupted any flow the text had. While the early chapters fill out Mill’s life well, that falls away in favour of ever finer-grained examination of his ideas, arguments, and publications, despite the subtitle: ‘A biography.’ I found almost nothing about his forty (40) years of work for the East India Company, though the author does suggest that his responsibilities were comparable to a cabinet minister. I stress this reference to India because the last pages of ‘Considerations on Representative Government’ say somethings about India that give one pause. Indeed the last lines refer to India as ‘semi-barbarous.’ His tenure with the East India Company included the Sepoy Rebellion, so it was not all business as usual.

Nicholas Capaldi

Nicholas Capaldi

The wheel turns. James Mill and Mill did much to govern India from London and today India does the same for Britain through those call centres. In fact, there is so much demand for Indian call centres, I discovered, that Indian companies are sub-contracting many of them to the Philippines. I am pretty sure that recently when I called AusGrid to report a burned out street light outside our front door, the agent I spoke to was probably in India, the accent, the slight lag in voice transmission, the formality of word choice…maybe.

Black Bird by Michel Basilières (2004)

Genre? Novel. Style? Northern Gothic, certainly. Magic Realism, maybe. Rating? * * * *

What happens in it? It is a circus of characters and incident. Part satire and part hyperrealism.

In her one-woman struggle to free Québec from the evil Anglos young Marie inadvertently blows up her maternal grandfather who becomes a spectral observer thereafter.

The Francophone police officer shown is trying to defuse an FLQ bomb. It blew up and left him maimed and crippled.

The Francophone police officer shown is trying to defuse an FLQ bomb. It blew up and left him maimed and crippled.

Her feckless twin brother Jean-Baptiste is irritated that with his own name in Montréal he cannot read French. The crow that Aline keeps in the kitchen attacks Grandfather. Tabernac! The FLQ consists mostly of spies in the pay of the Gendarmarie Royal.

Grandfather before and after losing the eye pursues his profession with father. They are grave robbers and Mont Royal is their hunting, well, digging, ground. They are accustomed to finding others, living there and work around them. But once the ground freezes in November, they have to wait…or do they?

In a ramshackle, decaying house three or is it four generations of Desouches live. Grandfather, father, and uncle, as our narrator terms them, shun the company of neighbours. This is another uncle apart from the one who was passing the letter box when Marie’s bomb went off, heralding a new era of freedom for Québecois. Then there is mother and Aline. I found it hard to keep the family straight. I started to make a score card, but that slowed down the reading, so I stopped. Pace is everything in these pages.

Father does not join the grave robbers, preferring instead to do nothing at all. He is surprisingly energetic in this pursuit.

Basilières includes the FLQ Crisis and the War Measures Act with René Lévesque’s manslaughter, the murder of Pierre La Porte with his own crucifix. Salutary reminders for those who find Canadian politics boring that boring is good compared to the alternative. The Montréal Basilières’s conjures from his keyboard lacks only voodoo and Spanish moss to be a cold version of mysterious and eerie New Orleans found so often in the popular culture in Southern gothic novels.

The Christmas gifts Jean Bapiste and Marie exchange in their mutual incomprehension are treasures. He only knows and relates to books but he is dimly aware of Marie’s activities. Ergo he gives her a copy of Carlos Marighella’s 1969 ‘Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla.’ She supposes he means it as a condemnation of her feeble efforts, and flies into a rage. But not before she gives him a blank book to show her contempt for his reading and writing, and he takes it to mean she wants him to write in the book and he immediately sets to to work to do it and indeed does. (It is a blank note book bound to look like a book. Their misunderstanding is complete and to the core.)

The subsequent account of the performance of the play that emerges from the blank book is a wonderful satire on everything it touches from the producer-director to the audiences. Nothing is sacred. Calice!

Fact is one thing and fiction is another and this is fiction: This is a Montréal populated by grave robbers who siphon off the neighbour’s natural gas to heat their ark but cannot control it so that house is an oven during the coldest winter, a Montréal where Felquiste and Pequiste hate each other and no one but them cares one whit and that drives each of them to new heights of frustration, a Montréal where a glass eye offers better sight that the real thing, a Montréal where the timeline of history bends….

It is no accident that the family physician is named Dr. Hyde who is a famous surgeon and yet is ready and willing to make house-calls to the Desouches (because they supply what he demands – see above). The good doctor does his most important work alone at night, and has some unexpected success.

Michel Basilieres

Michel Basilieres

Marie becomes an avenging angel and single-handedly kidnaps the British Trade Commissioner and later she strangles him to death with his own rosary chain. It is Rated-R and rather gruesome, and she, of course, finds it difficult to do and to live with, but…. Then there is that lousy gas connections, and boom, many problems are obliterated. Marie, in another time and place, would have been a postulant in a convent such as imagined in Ron Hansen’s fine novel ‘Mariette in Ecstasy’ (1991), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

One of the most exhilarating novels I have read. I came across it in a Montréal bookstore while walking some of the streets described in it and that added a frisson the first time I read it in in 2009. It came to mind recently as I read a few things about Canada and Québec so I sat down with it again. Great fun. Gabrielle Roy chronicled Montréal life in a series of wonderful novels in the 1940s and 1950s. Wry, gentle, bemused and serious, they are. In this book, by contrast, nothing is serious nor sacred. Though it is deeply ‘de vieille souche’ as they used to say on that island in the fleuve St Laurent, it was written in English. Those among the Québeceratti who take themselves ever so seriously avoided any mention of the book. The contemporary reviews I found were all in English in English-language publications. One of which chides the author for mashing together the FLQ crisis and the PQ government and confusing Pierre LaPorte with James Cross. Not everyone gets the point, it seems.

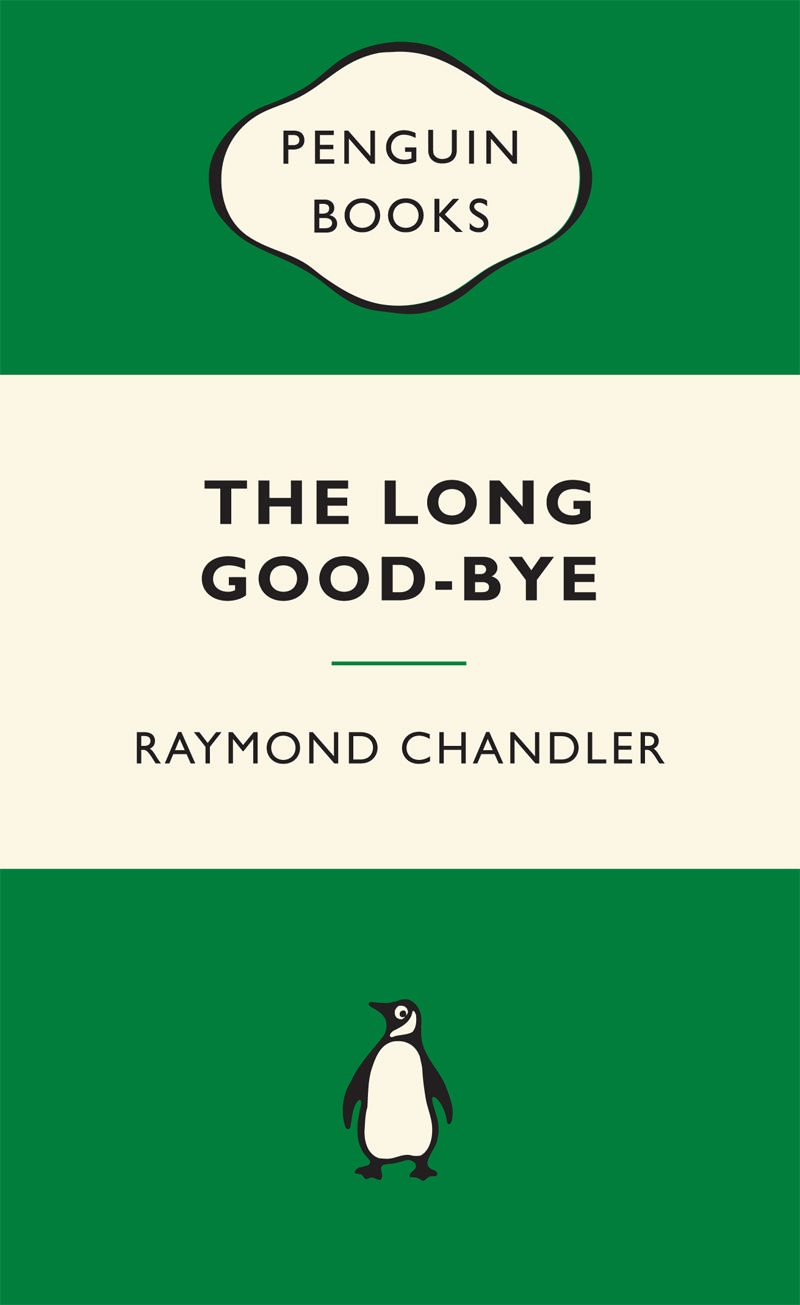

Raymond Chandler, The Long Good-bye (1954)

After reading Benjamin Black’s continuation of this title in ‘The Black-eyed Blonde’ this old favourite was on my mind when I saw it on the shelf of the Megalong Bookstore in Leura.

This is Chandler’s last complete novel and it is twice as long as any of his previous ones. Indeed it was very long for the genre when it was published. I thought I would read a chapter or two before bed the other night and found myself on page 100 at midnight, such was the flow of characters and events. Another four nights and I was done. Of course, I had read it before and then Black’s book had refreshed some of the characters for me.

Beginners can start here. Philipp Marlowe meets an odd character, one Terry Lennox, whom he gets to like and sees now and then over several months. Very early one morning Lennox appears and asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, no questions asked. Marlowe agrees, opening the can of worms that wriggle out over the next 400+ pages.

Once again Chandler proves expert at pace and development. It moves but the reader can follow, and as it moves the characters and situations are fleshed out. If he describes the clothing a character wears it is because it reveals a social situation, an attitude, the money, something about the person that comes into the story. No description is an end-in-itself in Chandler; it serves a larger purpose, or it is omitted. Scores of contemporary writers should learn that lesson.

And he differentiates characters one from the other, even if the appearance is fleeting. The jailer who opens the door to the cell where Marlowe will sit and ponder friendship for three nights says nothing, but he is etched in his posture, his walk, his silent appraisal of Marlowe. Nothing is said between them but they understand one another: Marlowe will make no trouble and the jailer will leave him alone. The tough talking newspaper man is a stock character, yes, but this one is just a little bit different, an individual, neither a stereotype nor a plot device. The cab driver who declines the tip has his reasons. The several police officers are each individuals, some very unpleasant, some vacuous, and some well-meaning but exhausted, all different one from the others. Then there is the New York publisher who tries to do the right thing but cannot quite see what that is.

Another lesson for today. Too many, far too many krimies that I try to read now present a parade of characters who all effect the same speech patterns even when they ostensibly represent a variety of backgrounds because, I guess, the authors cannot control the language, or worse, do not perceive the similarities. Neither is a recommendation.

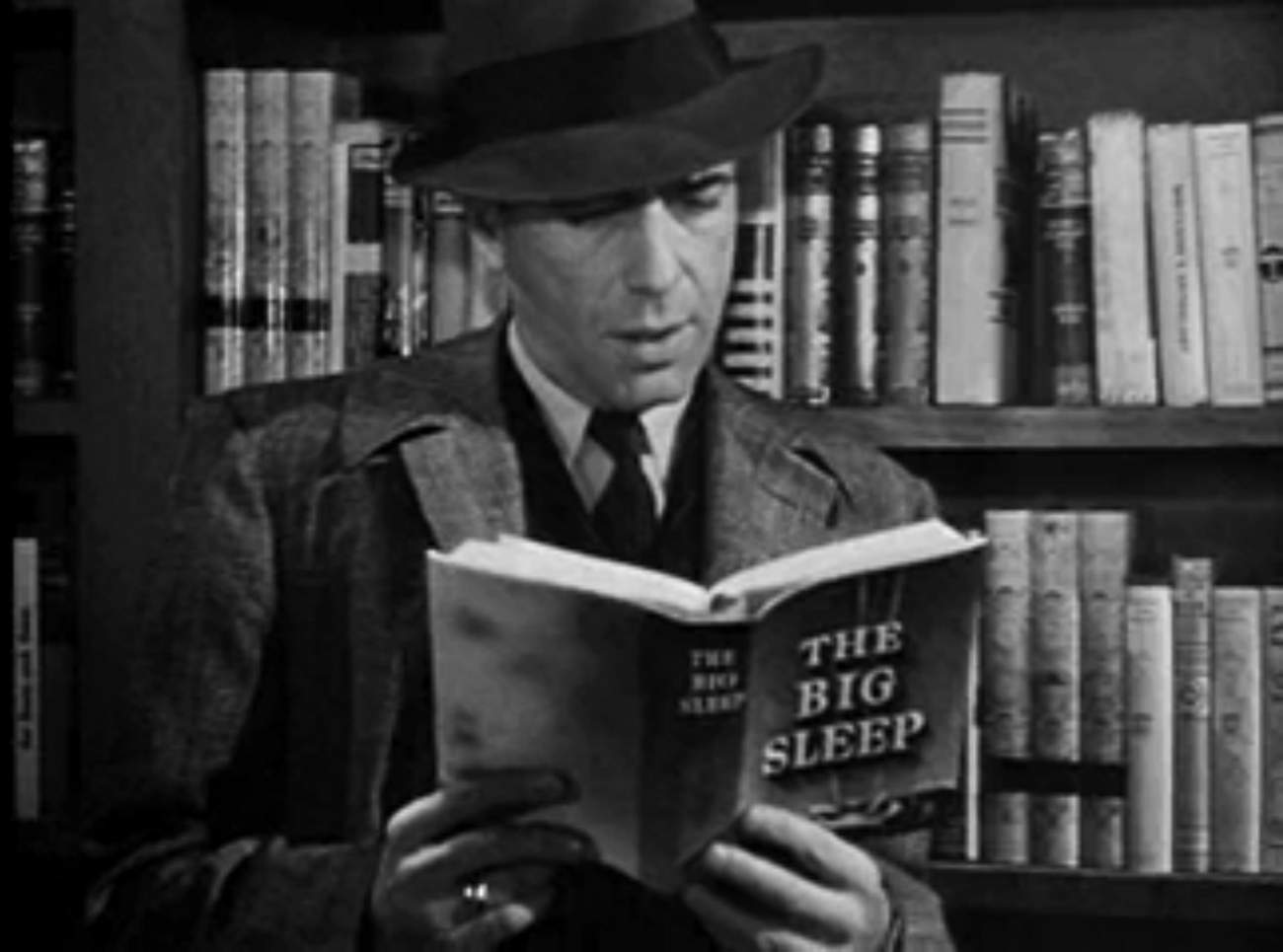

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Then of course there is Eillen Wade, or as Marlowe calls her: The Dream. The page crackles when she walks in. That one man in the room does not look at her is a sure sign to Marlowe that he is up to something.

In the six Marlowe titles we learn almost nothing about Marlowe but here, when quizzed, he says a few things about himself: born Santa Rosa, parents dead, only child, played football once…to explain some crooked teeth. So much for the backstory in a half a dozen lines. Chandler’s focus is always on the here and now. This focus keeps the story moving and also preserves Marlowe’s mystique. Contrast this spare account with the verbose backstories that derail the action, if there is any, in so many contemporary krimies. I read one recently that interrupted the action with a 100-page backstory about the protagonist, at which point I quit reading it. (No this back story did not tie into the story, of that I am sure.) It was like listening to the drunk in a bar who wants to tell whoever is there his own fascinating life story. No thanks.

If Chandler’s prose is economical, decisive, and penetrating, the dialogue is even better. Chandler had an ear for the spoken word. If the descriptions single out individuals, their talk clinches it. Superb.

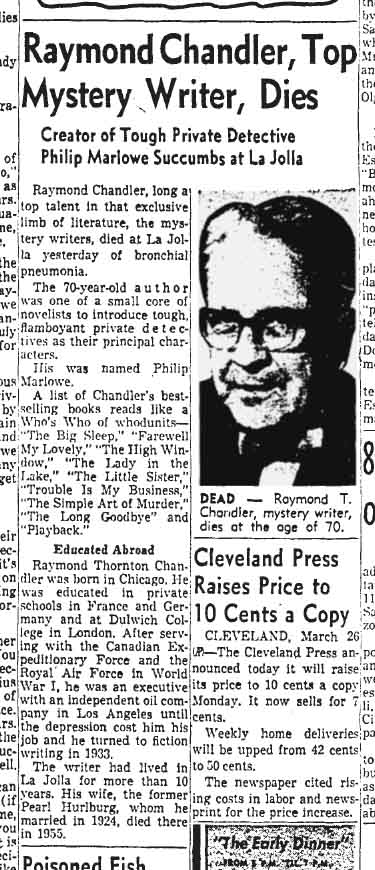

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

I have read this novel at least once, perhaps twice before, and I had a very strong recollection of one of the minor characters, Earl Wild, at the ranch. I anticipated his appearance and he did not let me down, but I was surprised, given the memory I had of him, how brief is his appearance on the page. Very brief. Likewise, I remembered though not as vividly the T. S. Eliot quoting chauffeur Amos in the last few pages, Chandler’s riff on pretentious literature.

The central character in the book is Chandler’s alter ego Roger Wade who, like Chandler, is a genre writer whose work sells, for reasons he cannot fathom, but that wins him no respect as an author. When Wade hits the bottom of the bottle, a frequent occurrence, he spouts self-indulgent nonsense and feels sorry for himself with great eloquence and energy. Wade is Chandler in all respects.

When Chandler wrote this book, we now know, his own wife was dying of cancer and he spent many nights and days with her at the hospital, and turned to the typewriter to escape that reality. One biographer speculates that the book is as long as it is because its composition coincided with her agonising death. A morbid thought, but it explains the mood swings and oscillating character of Roger who is also bearing a different kind of burden from his wife, she being The Dream, as above, or as Linda Loring calls her, ‘the Golden Icicle.’

No review is complete without a barb. Chandler does not manage quite as well with the rich and obnoxious characters, like Harlan Potter or Dr. Edward Loring in this book. Both are at the cardboard end of the continuum. There to be hissed at and booed. Nor is Linda Loring quite right, either, though for different reasons. I never did form a clear impression of her. The backstory of Lennox, Mendy Menendez, and Randy Starr just does not compute.

The book has a foreword, well I guess it is that, but the publisher coyly does not call it that, instead titling it ‘Jeffrey Deaver on “The Long Good-bye”.’ The real mystery is why the publisher bothered to include it. Is the hope that Deaver’s readers will, Pavlov-like, follow him to purchase and read Chandler, or simply to squeeze some more work out of Deaver’s contract? If the former, it is a well-kept secret since it is not trumpeted on the cover (see above) to lure in those Pavlovian readers. If it is the latter, it is a wash-out. Deaver’s remarks are few, banal, and trivial, as well as factually incorrect when he writes that the story takes Marlowe to Mexico. Not so. Marlowe goes no further than Dr Verringer’s ranch in Los Angeles county. Deaver’s main reference to the text is the opening lines, perhaps he got no further. He also says Chandler’s prose is like Hemingway’s. Yes, he does! Staccato. That is Hemingway. Short and sharp. To the point. One point is one sentence. Subject, verb, and object. End. If it has to be said, Chandler’s prose is not like Hemingway’s. Really, Jeffrey!

In 1954 the ‘New York Times’ reviewer, Anthony Boucher, said it was the best of the best, and Chandler’s peers voted it an Edgar award. Boucher also remarks that this novel has a strong theme of social criticism about the society and situation that produces these crimes with less of the sardonic resignation of some of the earlier Marlowe novels.

It took Hollywood twenty years to get around to it, and then to make a hash of it. Nuf said on that subject.

This publisher changed Chandler’s ‘tires’ to ‘tyres’ but stuck with ‘z’ in ‘organize’ and ‘finalize.‘ At least once a ‘he’ appears where it should be a ‘she’ and elsewhere we have ‘ice’ for ‘eyes.’

One question I always ask the inner Elmore Leonard at the end of a novel is, ‘Could I edit it down in length?’ In this case, if I worked at it I would cut and shorten a few scenes and reduce by, say, half-a-page. It all adds up, even Roger’s drunken ravings, tedious though they are to read.

Mark Adams, ‘Meet me in Atlantis: My Obsessive Quest to Find the Sunken City’ (2015)

‘Obsessive?’ ‘Obsessive!’ Yes, indeedy.

From little asides big myths grow. The sum total of human knowledge of Atlantis comes from a couple of pages in two of Plato’s dialogues, the ‘Timaeus’ and the Critias.’ These two are not in the first rank of Platonic dialogues. A great many admirers and readers of Plato have never heard of them.

The ‘Timaeus’ is a conversation set the day after the conclusion of the discussion of the ‘Republic.’ (Since there is no republic in it, for millenia pedants always wonder about that title. Answer: It was bestowed on the work by Cicero hundreds of years after Plato’s death. Cicero was not much interested in accuracy, think of him as a Fox journalist. No doubt it suited his purpose to have Plato legitimate a republic on the assumption that no one else would read the whole book.)

In turn, the ‘Critias’ continues the ‘Timaeus.’ In the few lines that mention Atlantis it is at a great remove from Plato. It is allegedly a story that an Egyptian told Solon hundreds of years earlier that is reported by one of the interlocutors. It mixes very specific details like the colour of building blocks, and the measurements of temple while being maddeningly vague about where the place was except for a reference that has been translated as ‘beyond the pillars of Hercules.’

What with all his labours, Hercules seems to gotten around the Mediterranean. Atlantologists have located the pillars at Gibraltar, Malta, Messina, Crete, Santorini, Morocco, the Crimea, and, believe it or not, Ireland. Yes, Ripley this really is ‘Believe it or not’ country.

Our cicerone is not quite right in that subtitle above. The book is not about his quest so much as that the other Atlantogolists he seeks and meets. Some he sought out in libraries and archives, and others on the internet, and he went to meet many of them in person. The book is a travelogue about the Atlantologists from Ireland, Germany, Morocco, Sicily, Greece, Malta, United States, Great Britain, and more. He had some travel budget did Mark.

The one place bruited as Atlantis that he did not visit was…. Antartica. Yes, Antartica has been identified by some as Atlantis, which drifted south after a cataclysm.

The tone is light and the prose snappy. While he is not a true believer in the Big ‘A,’ there are no cheap shots at those who do believe in Atlantis. This is no Bill Bryson hatchet job passed off as humour.

He does call the many interpretations of Atlantis ‘theories’ and that annoyed me because they are speculations, not theories. A theory joins evidence and analysis. Speculation is guess work without either.

The many ways in which Plato’s few lines are interpreted include, deciding that he meant 900 and not 9000, and the latter is a transcription error made by a scribe in ancient Egypt. Well, yes, it could be, and that scribe might have had red hair but however are we to know?

As for the ‘pillars of Hercules,’ every part of that is deconstructed and reconstructed to suit the desires of the speaker. ‘Pillars’ can refer to many things, far more than I ever thought. And Hercules, well he was several other chaps with the same name all over the place like John Smith. On it goes. The Wikipedia entry is a site of constant conflict. It changes every day as the Atlantologists slug it out on their keyboards.

When I first read the ‘Timaeus’ I thought the reference to Atlantis there was an undeveloped allegory on the hubris of peoples, not a road map. I took it to be a parallel of the Allegory of the Cave, and no one has yet set out to find that very CAVE. Silly me, once again I missed the point.

Some of the Atlantologists he met are safe, safe, and sober who discount the wild speculations of the many more zealous of their number, but find the subject fascinating. One of these triple esses (safe, sane, and sober) runs a web site: atlantipedia.ie.

Others are obsessive, no doubt about it. Any claim Mark Adams has to be being obsessive is bleached out by some of the characters he met. Among them are those that cannot make eye contact, talk in 45 minutes monologues and then lapse into catatonic states, talk to him through doors for security reasons (someone might steal my Atlantis map if I let anyone in). These are not in the safe, sane, an sober zone of inquiry.

Some promote a location, like Sicily, Santorini, or Malta, as Atlantis for purely venal reasons: it brings a few tourists (even if they are nut-cases, they pay hotel bills).

One of many maps on the internet.

One of many maps on the internet.

Mixed in among these types are a collection of serious archeologists who are studying ancient ruins here and there and whose work, an Atlantologist thinks, has something to do with Atlantis. Huh? Well, goes the interpretation, these archeologists keep secret their interest in Atlantis, (a) because of the conspiracy of the rose (on this, see below) or (b) their funding would be cut if they admitted it. Maybe this is the paranoid side of the coin. Or (c) they foolishly do not realise the connection to Atlantis.

One of many representations of a building on Atlantis.

One of many representations of a building on Atlantis.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) called his little book in praise of science ‘The New Atlantis’ and in it speculated on what science could do to conquer nature and improve humankind. Because of the great powers of science for ill as well as good, Bacon imagined its use confined to a sect who worked with this secret knowledge for the good of all on an island. (Yes, this is the same Bacon who wrote the complete work of Shakespeare according to some….)

Francis Bacon (I have seen this image passed off as Machiavelli more than once, believe it or not, Ripley.)

Francis Bacon (I have seen this image passed off as Machiavelli more than once, believe it or not, Ripley.)

Fatherhood followed. He sired, as so many have claimed, without knowing it, Rosicrucianism. This doctrine has followers today at your nearest public library, though they will not wear a rose on the lapel.

The rose cross,

The rose cross,

Start checking out, reading, asking about books on Francis Bacon and the Followers of the Rose will ever so subtly make themselves known. They live and breathe conspiracy, arcane knowledge, numerology, and a lot else not to be found on the curriculum at a university. (Not yet, anyway. I omit Pepperdine, where shoe tying is an advanced course.)

Where else? California near San José.

Where else? California near San José.

It is proof positive that Atlantis existed to the Rosicrucians that NASA named a space shuttle Atlantis. That was, they say, a coded message not only to Earthlings, but to aliens, as well. Gulp! Yes, there is an Erich van Donkey element to all this. The spell-checker changed the egregious Swiss hotelier’s name to Donkey and I decided to accept it as fitting.

Adams meets a few of the adherents of the rose along the way, nods a lot in agreement with them, hides in the bathroom to avoid others, and leaves town as soon as possible when he encounters a coven of them. Reading of his experiences made me wonder the Rosicrucians had never figured in ‘Midsomer Murders.’

Jules Verne, Walt Disney, Star Gate, an eponymous television series in 2013, and scores of others have made use of the name recognition of Atlantis, and in so doing have scattered its seed further, and by repetition perhaps planted it deeper. A google search returns a gazillion hits or 110,000,000 without even working up a sweat.

Mark Adams

Mark Adams

Having made light of it all above, I must conclude by saying that Adams does shift the evidence and evaluate the arguments he heard, without denigrating anyone, and concludes, with a phalanx of qualifications, that the ancient city of Tartessos near Cadiz in Spain is the best candidate. That is, if there ever was an Atlantis. This city has a genealogy as Tartessos but perhaps Atlantis previously occupied the site before it was obliterated in a tsunami. As to the details Plato gives of colours and dimensions, these might simply be artistic touches of verisimilitude that can be dismissed. Hey, presto! We have arrived at Atlantis!

Thus inspired I re-read the ‘Timaeus’ and the ‘Critias’ to see for myself where the fire started. The reference to Atlantis is brief in the former and continued in some tantalising detail in the latter. In the ‘Timaeus.’ An Egyptian priest told Solon, who upon his return to Greece told Dropicles, who told Critias’s grandfather who told his grandson also named Critias. These four tellings span the two hundred years from Solon to Plato. That make me think of those ‘pass it on’ exercises in school. The teacher whispers in the ear of the first child ‘The sky is blue,’ now tell your neighbour and by the time it went around the class, the ceiling was falling. The morale of the story in that case was do not believe everything said.

The ‘Critias’ has all those details that have set Atlantological hearts a-pounding. Distance, dimensions, durations, depths, and more, all of which are well canvassed by Adams.

Reading it now the point of the story seems to me to this: As big and powerful and grand as Atlantis was, our noble ancestors, the Athenians, defeated them. Atlantis had all the wealth and power but this pre-historic Athens had all the virtue: they held all things in common, the warriors lived apart as warriors, features in the fictional city of the ‘Republic’ now given an Athenian pedigree and a track record of success. And why does not the Greek in the street know this already, why because a flood swept away Atlantis and most of Greece, too, so angry was Poseidon at the hubris of the Atlanteans. This devastating flood killed all the literate men who might have remembered or recorded the story, sparing only a few rude and crude mountain men from whose loins Athens was eventually re-populated. This flood stripped Attica of its topsoil and carved the Athenian acropolis out. End of story.

Get it? Atlantis was big and powerful but no match for a virtuous Athens. Athens was virtuous because no one there cared about gold, jewels, luxuries that the Atlanteans had in plenty.

René Lévesque (2013) by Daniel Poliquin

René failed because he succeeded. Ever a paradox.

Many people loved René and many people hated him, and still more both loved and hated him. He is the one person whom I would say was charismatic. He burned with a message akin to those religious prophets that Max Weber coined the word to describe. I saw him once in person in a very small audience in Edmonton, and many times later on television. There are plenty of clips on You Tube. But, well, you had to be there to feel the electricity in the air. At the 1980 defeat the rapturous crowd response and his simple and direct statement: ‘I understand’ perhaps suggest his quality. Remember this is the leader addressing the troops in defeat. It is on You Tube.

The book does not try to be a biography inquiring into the growth and shaping of the man, but is rather a summary of his life and career. It filled in many gaps for this casual observer.

Readers who do not know René can start with the three facts.

1. He was always called René by everyone from bus drivers. journalists, enemies, admirers, voters, opponents, to body guards. Like the eponymous television characters Lovejoy or Morse, René had only one name.

2. When he resigned from office after nearly a decade and cleared out his one bedroom apartment where a plastic milk crate served as a coffee table, he took away his worldly belongings in a plastic supermarket bag. He had long ago given his apartment in Montréal to his divorced wife. (He lived his short years in retirement on his parliamentary pension.)

3. The epitaph from one close and sympathetic English-Canadian observer was: his words stopped more than one riot.

He was from Gaspé, a distant and isolated region where the living is hard, but his family had connections. He was a lousy student and dropped out of Laval University in 1944 for military service. But unlike the Québécois hero of Hugh MacLennan’s ‘The Two Solitudes’ he did join the Canadian army.

René did everything his way: He went south and enlisted as a translator and liaison officer in the United States army serving in Europe with Patton’s Third Army. He saw Dachau within days of it liberation, and that vision stayed with him for the rest of his days. In 1950 he went to Korea as a correspondent, this time with Canadian troops.

Like many, veterans and not, he later embellished these experiences in many ways, but somehow managed to live those fictions down. He did tell lies, to make it plain.

The author suggests three legacies his 1944 experiences that forever shaped the man:

1. Democracy. He arrived in London in 1944 to a society under siege, yet he saw Hyde Park orators excoriating Britain for its coloniziation of India. Here was a country on its knees, everything rationed so thin as not to exist, with nearly every man and woman in a crude uniform – some with wooden rifles, V-rockets falling every day killing thousands, and yet during all-clears polite Indian orators excoriated England to attentive and polite crowds. If that was democracy, it was what he wanted.

2.Les maudits Français. He never had any interest in or respect for France. Later when he met French presidents and foreign ministers, he seldom did more than go through the motions. De Gaulle’s (in)famous remark from the balcony of town hall in Montréal, sent René into a rage. Another Frenchman interfering in something he does not understand. More colonialism!

3. Dachau was the outcome of blind nationalism. Never will he do, say, or acknowledge anything that goes down that road.

He become first a radio broadcaster and then a television presenter who explained the world to Québécois(e) in the 1950s. The backward nature of Québec in the period is hard to believe. Maybe one fact says it all. In 1875, yes in 1875, the provincial government of Québec abolished its Department of Education. It vacated education, leaving it to the Catholic Church. Few children went beyond 6th grade. Most girls left sooner. The curriculum was approved in Rome.

On television his genius for keeping it simple paid off. He soon had his own program ‘Point de mire’ (Focus). The author makes it clear what a refreshing breadth of air he was on a medium largely dominated by the sanctimonious and inscrutable at the time. His viewers were working class Québécois(e) and he spoke directly to them. Other presenters spoke Parisienne French, many were from The Church, some even spoke Latin on Radio Canada, most talked either down to the audience or over its head. All were dead boring. (For the literal minded, note that Radio Canada broadcasts both radio and television.)

Then came La Revolution Tranquil and he was recruited as a Liberal candidate and within weeks was a cabinet minister. He had zero (0) relevant experience. He had never managed a staff or a budget, and had never delivered anything concrete. Yet he was a whirlwind.

In a few weeks he convinced a cabinet, where there were many long-serving foot soldiers who resented this celebrity candidate, to nationalize electricity!

René, ‘My way or else!’

René, ‘My way or else!’

Hydro-Quebec was born, and it employed French-speaking engineers, accountants, technicians, specialists, receptionists, linesmen, repair crews, damn builders, managers, and secretaries. These skills in turn had to be learned and taught, and the Department of Education was rejuvenated.

The Québec flag atop a building with the Hydro-Québec logo

The Québec flag atop a building with the Hydro-Québec logo

Along the way he upset many apple carts, like putting every contract to public tender. Incoming Liberals had rather been counting on rewarding supporters with contracts on the sly, and here was a minister who made it all public. Reluctantly, others had to follow…the leader. He also closed his door to contractors who wanted to woo him. Non! It all goes through channels and all the channels are public. Again other ministers found they had to do likewise.

The old saying is that every Québécois is an independentist at least an hour a day. René’s experiences as a minister led him quickly to conclude that Québec could only become a modern society if it ran its own house. The financiers in Toronto called the shots to benefit themselves. The Church wanted acquiescent worshippers. The politicians in Ottawa were always looking to an abstraction called Canada. For both, leaving Québécois to hew trees for paper and draw water for hydo-electricity was enough. Backward, barefoot, and pregnant would be fine. The colourful natives can stay that way.

In a few years he started a movement to secure a special relationship for Québec within Canada that morphed into the Parti Québécois, and a few years later he was the PQ premier of Quebec. It was a roller coaster ride.

He prevented riots. When Pierre Trudeau faced down the rioters himself in 1968, René was also hosing down the hot heads, and he had a lot more credibility with them than Trudeau. These two, Trudeau and René, were well acquainted and they lined up on different sides, Trudeau for Canada first and last, and René for Québec first and last. For a decade or more their axis dominated Canadian politics. Each had wins; each had loses.

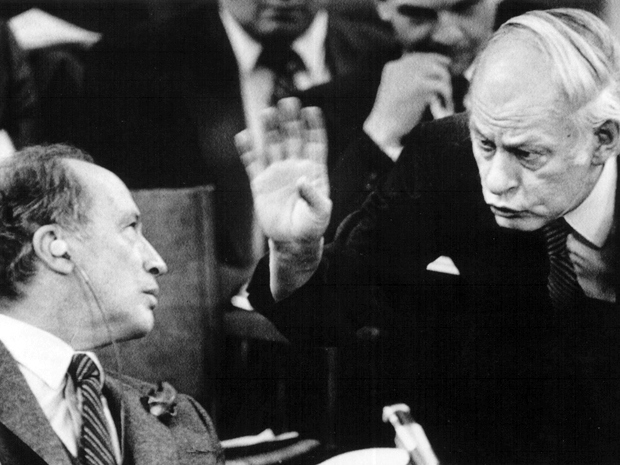

Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque

Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque

The rough rides included the FLQ crisis and the War Measures Act that put armed troops on the streets of Montréal. As much as René reviled the War Measures, he was the first and the loudest to condemn the FLQ and stopped more riots. Years later when a convicted FLQ member (having served his time and out of jail) entered a PQ rally, René slammed down the microphone and stormed out. He would NOT be in the same room with that murdering scum. (Though that individual was not himself a murder, he had conspired with them.)

This latter was a card he played often to keep in line the Saint Bartholomew’s circus that comprised the PQ. Do it my way or get a new leader!

A few more bumps in the rough ride include these: two failed referenda on sovereignty, manslaughter, a soldier shooting up the Assemblé Nationale in Québec Cité, and a double agent. Who said Canadian politics is dull?

René the democrat accepted the referenda results, and saw to it that even the zealots in the PQ accepted the results, too. That took a lot of doing, and another threat to quit. Another riot averted.

A Canadian soldier killed three people in the Assemblé Nationale in an effort, he said, to destroy the PQ government. René was not in the building at the time but he hosed down the reaction. No riot this time either.

The manslaughter occurred when René drove home after a long, acrimonious meeting in a bitter January winter snowfall, having drunk — no doubt too much — French wine he ran over and killed a homeless man. The victim was well known to the police for harassing motorists and lying on the road to make them stop so he could ask the drivers for money. René ran over and killed him in the snowfall and called the Sûreté du Québec. Given his many enemies, including aspiring rivals in the PQ, that he was exonerated is convincing. (Note: my driving experience in Montréal left me with a strong impression of hostile and aggressive pedestrians. Nowhere else did I met people who, passing by, yanked open the car door to ask for money, a ride, or pass an opinion on out-of-province license plates.) This event is recounted in Michel Basilieres’s Québec Northern Gothic novel ‘Black Bird’ (2004), which I enjoyed enormously.

The double agent? It turned out that one of René’s closest cabinet colleagues had been recruited years earlier by the Gendarmerie Royal du Canada (RCMP) to inform on radical student groups and he continued to take the payment thereafter. When confronted with the facts, as only René could do, face-à-face, the minister argued he had penetrated the RCMP for the cause! An explanation that René did not dignify with a reply. Well, he did reply: NON!

Perhaps René’s finest hour came the day after he resigned as premier. There was the ceremonial dinner. It was all conducted in French among 600 guests from the political, administrative, media, lobbying classes. At the end René spoke English to invite the one person, having sat through several hours, who spoke no French to join him on the podium and to speak to the assembled group in his language. This man who had come a long way at his own expense spoke Inuit and thanked René for his years of effort at improving the lives of the First People above the Arctic Circle. Indeed, René had done so much that other provincial premiers and finally the Federal Government had had to match his efforts in education, health, welfare, and more.

But the medium was also the message. We can speak our language; so can he.

That should whet any appetite. There is more in the book.

The author pulls no punches and it is a better book for it. René told lies at times. He was prone to self-dramatisation, as if his life did not have enough drama. He was bad father and a terrible husband, and treated the many women in his life as disposable. The confrontational ‘F off, I am indispensable, and you’re not’ was used too often later in life when the patience of this impatient man was exhausted.

He drank to excess, and was sometimes legless and when so, he was rude and crude.

He was nearly a midget with a bulbous head ever more revealed by thining hair, an outsized nose with a drinker’s veins in between ears the size of hockey gloves. He had one suit of clothes and when it decayed he bought another of the rack. His clothes were always smeared with cigarette ash for he was a chain smoker; the 2-3 packs a day were what killed him.

Charisma indeed! Whatever it is, he had it. Yet he was not handsome or good looking in any sense. He was not saintly in any way. He did not sound like an oracle. He seldom smiled. Told no jokes. Was no glad-hander or baby kisser.

He was completely indifferent to money. When the police took him in after the manslaughter he had $5 in his pocket. When died he left a bank balance of $2,800. He assigned the royalties of his memoirs to an Inuit trust in his will.

Daniel Poliquon

Daniel Poliquon

The author’s summation is brilliant. René failed because he succeeded. To explain, he failed in the referenda because he had already succeeded in imbuing Québec and Québécois with the self-confidence to become master of chez nous without sovereignty.

Jules Romains, ‘Men of Goodwill,’ volume 1: ‘The Sixth of October’ and ‘Quinette’s Crime.’

Jules Romains, ‘Men of Goodwill’ is the longest novel ever, running to twenty-seven (27) titles. Yes, 27! They have all but disappeared. Few libraries have the whole set, and finding a set to purchase was a long chase for me. They appeared in an English translation in the 1930s. Each volume contains two novels, apart from the last.

In this, volume 1, there are two novels: ‘The Sixth of October’ and ‘Quinette’s Crime.’

Romains’s description at the start of Paris awakening, stirring, moving on a working day is wonderful. He was a believer in some kind of collective consciousness in crowds and he sees this in patterns, recurrences, and actions and reactions on streets, in the Metro, on buses, in employees clocking in, bicycle riders at a traffic light, trucks backing into loading docks at les Grand Magazins.

Monsieur Quinette spontaneously hides a murderer and involves himself in the crime for no other reason than boredom, and because he is, he thinks, so much smarter than anyone else. He misleads the police, extracts the dosh, but finds Leheuday, the murderer, a thug and a loose cannon. He decides to off Leheuday, nick the dosh, and perhaps take Leheuday’s rather dim girlfriend, while leading the police on a merry dance. Deciding is slow work and his last scenes with Leheuday are interminable. But in the end, bang, bang, and he is dead.

It takes Quinette both volumes to shoot Leheudey who murdered an old women in the opening pages. In another of the several threads started in these opening volumes, the students Jallez and Jerphanion meet and they continue through the remaining volumes I think.

Jalllez and Jerphanion become friends, and the Minister of State Gurau discovers a plot against him. He is another who thinks he is smarter than those around him.

The street scenes are well described. The interior monologues of Quinette and Gurau are well done but they go on too long.

Jules Romains, who broadcast for De Gaulle from New York.

Jules Romains, who broadcast for De Gaulle from New York.

The whole 27 volumes together comprise an encyclopaedia of Parisienne life — the high and the low. It reads rather like an encyclopdia, earnest, accurate, detailed, and bloodless. Still the characters are differentiated in manner and speech as part of the ethnography of types and the descriptions of Paris are cinemagraphic.

Alan Furst, ‘Red Gold’ (1999)

An espionage thriller from a master story teller who conjures an atmosphere of melancholy from a few lines. Most of the story takes place in grey drizzle with characters who get by on 1500 calories a day, wearing paper thin coats in the unheated rooms of Occupied France in early 1942. They are Jews, bystanders, communists, socialists, citizens, refuges, unionists, journalists who get caught up in each others’ schemes, some petty, some heroic.

The fear, the deprivations bring out the best and worst in people. Pretty Victorine in the travel agency sucks the Jews dry and then turns them in the Gestapo. A gendarme leaves the back door open while he goes to sharpen his pencil and the suspected resistant walks out.

The communists of FTP trust no one, certainly not each other. Students do half-baked, stupid things and get killed. These martyrs inspire others to do more stupid things, and so it goes. German reprisals grow in scale and scope. Life is the one, the only thing that is cheap and readily available.

Grim.

The prose is laconic and spare. In this oppressed world no one has the time for long winded perorations, or for second thoughts. There is no food and hardly any clothing to describe. It meets the Elmore Leonard test. If it is there, then it is important. What is not there is unimportant.

I have read a few of his titles before, but I do find them so melancholic and so grim that there is little pleasure In reading them. It is clear that nothing good is going to happen. And nothing good does.