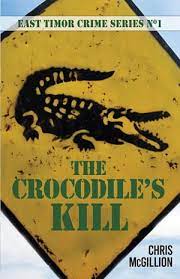

Crocodile’s Kill (2022) by Chris McGillion.

Good Reads meta-data is 284 pages. rated 3.29 by 7 litizens.

Genre: Krimi.

Verdict: Less of Timor might be more.

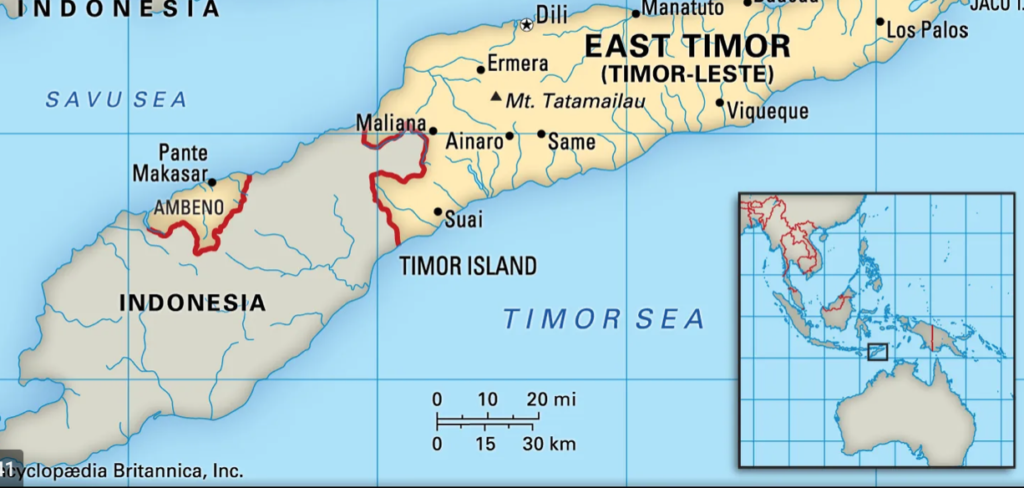

The set-up: Impetuous FBI agent is banished to distant East Timor (because no place in Mongolia was available) where she cannot do any harm and might do some good.

In Dili she is seconded to Interpol (yep, it still exists but Reinhard Heydrich is no longer the head) to investigate the systematic abduction of babies less than two years old along the Indonesian border. The scars – physical, social, and psychological – of the 1975 Indonesian invasion and occupation until 1999 of eastern Timor are still vivid there. Recent Timor history is sprinkled throughout to explain motivations and attitudes.

The local liaison officer is glad for any help, but, well, this one is high maintenance.

The characters are differentiated and varied. A host of locals pass by as this odd couple investigates. A third officer joins the pair as a translator, file clerk, driver….to earn her spurs in the field.

By the way, the titular croc is ….. (Read it for yourself.)

The book is free from the tropes that drag down many of the krimi samples I read. The action is not deferred for long and boring backstories. Too often these backstories are supposed to make the reader either identify with or feel sorry for the protagonist. Further, the local does not pout about the FBI agent he has to be shepherd. Wise, since she might punch him out if he did. Nor is his superior officer obstructive and stupid, a tired device to create tension, as if the front story was not important enough to do that.

There is no catalogue of descriptions of clothes and food. When these are described it is brief and in context moving things along. Nor are there tedious descriptions of the characters. I am not sure what any of them looked like and willing to leave it at that. The movement in the interior along the border is purposeful, not a travelogue. I followed it on Google Earth until fiction replaced fact.

Even better the characters are distinctive, one from another. They don’t sound the same or even similar, and not every nit is picked to death. More than once something comes up, and a character chooses to let a comment go through to the keeper. (That last phase from cricket has no exact analogue in baseball.) Not every point gets argued to dust in lieu of doing anything, as is often the case in the krimi samples I read and decide not to continue to the full text because they are too talky.

In order to flavour the story Timorese there are continued and repetitive translations from the local languages and Portuguese that wear a reader down. I take the purpose to be context, but well I got abraded by it. Reminded me of Alexander McCall Smith and that is no recommendation to my mind. Yes, I know this mislike puts me in (another) minority.

The plot, though distasteful, is arresting and the situation is certainly new to me, despite my years of krimi reading.

While there is much stress on the urgency of the investigation, there is plenty of time to describe the region’s recent, malign history. And the region has far too much history for those who have had to live through it, from the Portuguese occupation for hundreds of years (which ended overnight) to the Japanese for a few, with some Dutch intrusion, and the commercial exploitation of late, including now Australian contractors who are expert at cutting corners. Then there are those Indonesians whose map of Greater Indonesia greeted visitors to Jakarta airport for years; it included Timor, East and West, and all of New Guinea and Borneo all the way to the Solomon Islands. Though that map is no longer displayed it likely remains in the minds of many people.

P.S. I came to wonder if the FBI agent assigned to East Timor would have done some homework before travelling to the island. A few clicks on Wikipedia if nothing else.

Disclosure: The author is a pal of mine.