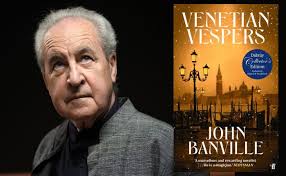

John Banville, Venetian Vespers (2025).

Good Reads meta-data is 320 pages, rated 3.66 by 372 litizens.

Genre: Mystery.

Species: Venice, death in

Verdict: What a chameleon.

Tagline: He didn’t do it, but it was done.

Author and wife go on a belated honeymoon to Venice in January 1899. She is an heiress to a great railway fortune and from the get-go strangely withdrawn, as she has been since her wedding day six months before. Of the wedding night, there has been no connubial bliss, nor any since then. (Look it up, Mortimer!) Moreover, she has now been written out of her magnate’s will in favour of her dowdy sister.

Thomas Cook has made all the first class travel and accommodation arrangements which were paid much earlier. Even so, damp, grey, cold, vaporous Venice is not welcoming to his senses. Don’t Look Now! To this, as to all else, Wife is indifferent. His efforts, few and feeble, to communicate with her are met with silence. Was it something he said? No onions next time!

They move into a cavernous palazzo on the Grand Canal and meet their landlord who is like someone from the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, a veritable grandee, or maybe he is an escaped extra from a Fellini movie. The palazzo has faded glory but neither heating, running water, nor plumbing. It is the true Venice experience.

At the start I thought I had grokked a homage to Henry James, in particular the Aspern Papers (1888), with the dependent sub-clauses from dependent clauses, attached to qualifying phrases in sentences that threaten to run-over the page. But not quite. Well, yes, some sentences did spill over the page, but it is not Henry James, whose genius was implicit, not explicit. I thought of that when I read the detailed description of the rape in marriage that the Author-husband exacted. Such might have been part of a James plot, but it would not have had a four-page description, but would have occurred off the page but nonetheless have been manifest. Well, not everyone is a genius.

After the rape, Wife scoots and Author, now ashamed, wanders around Venice, where he encounters an old school mate and his ravishing sister. In fact, he met them the night of the aforementioned event. Thereafter he makes few and feeble efforts to find Wife and lusts for sister who leads by his first friend.

There unfolds in the last few chapters a denouement that this jadded lag did not see coming, and it is a stunner. Indeed! It is convoluted but makes perfect sense in hindsight. Though perhaps it does depend on Author being dimwitted. And, well, six months!

A vocabulary builder: eructation, purblind, crapulous, plangency, and contemnor. This last ‘contemnor’ is used to mean someone who has contempt for some object or person. Uh uh, in a dictionary it means someone whom a court has found guilty of contempt. Iffy.

I had just finished re-reading Banville’s (as Benjamin Black) Black-eyed Blonde, marvelling as his ability to channel, and surpass, Raymond Chandler, when entering a bookstore in Bowral, this title greeted my eye. It seemed obvious I should read it, so I did. This time Banville came to the costume party as Henry James reviviscere.

Spoiler, big time. Close eyes if you are going to read the book. If I have made the right inferences, it goes like this. Father denies Wife permission to marry scoundrel Redhead. She then marries the Father-acceptable Author as a foil. However, she still falls out with Father. Why I don’t know. She then murders her father by staging an accident, and is surprised, though shows nothing, to find she has been disinherited despite marrying the dud Author. The considerable everything goes to Dowdy sister. Wife then manoeuvres husband in name only Author into the belated Honeymoon in Venice, planned and paid for before Father’s death. They have had sex only once the night before the marriage. So it has been a six-month dry spell for him. In Venice by arrangement Redhead and his Ravishing Sister insinuate themselves into the dim Author’s company. Wife goes missing as above. The Dowdy sister arrives and confronts Author over missing Wife. This argument is witnessed by many. She sics the police onto him. Then Dowdy Sister has a convenient fatal accident arranged by Wife. Now suspicion falls on Author for both the missing Wife and the deceased Dowdy sister. But wait, all along Wife has been sheltering at the British Consulate with a story of the rape as above. (Her plot did not depend on this rape, she could have faked it, or foregone it, but once it was done it integrated into the scheme.) All the while Ravishing sister has led Author by his member, while the RedHead manoeuvres around him insuring witnesses. Maids and such know of the unconsummated liaison with ravishing sister, which provides a motive, first, for disappearance of Wife, later to be supplanted by the rape, and, second, the murder the Dowdy sister who threatens exposure in suspicion that he has murdered Wife. In the end Author is not arrested since there is no evidence but sent off in shame, penniless. Wife inherits what Dowdy sister got from mega-bucks Father and marries scoundrel RedHead. Turns out Ravishing sister was married to consular official who connived in the plot in return for a healthy cut of the swag.

Connect those dots! That is a plot worthy of the darkest noir. Wife, redhead, sister, and diplomat conspired to murder dowdy heiress and implicate Author-husband. I think that’s it.