GoodReads meta-data is 292 pages, rated 3.7 by a paltry 9 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: All hail, Nerdboy!

The title says it all. Thomas Miller has compiled, annotated, watched, summarised, and commented on every movie (in the English-speaking world and more) that features Mars and some that do not and others that should. He includes cartoons, animations, documentaries, shorts, serials, and features. Did I say comprehensive? Comprehensive.

Miller’s telling is personal and there are asides and tangents but they, too, add to the overall impression of our fascination with Mars and the way it is manifested in art and life, including his own life. He climbed trees as a boy, looked at the stars, marvelled at stories of spaceflight, and became determined to work for NASA, and did. However, on with the show….

I was surprised at the long list of movies included. Many of the feature length fictions were familiar, but there were surprises even so. There is a chronological list at the end. The chapters are thematic: voyages to Mars, invasions from Mars, life and living on Mars…… But strangely nothing on Mars Bars.

It was a shock to find out how many versions there have been of H. G. Wells’s ‘War of the Worlds’ after the 1953 inaugural. I have lost count but typing that title in the IMDb will yield quite a harvest of literal remakes, and then there are those with slightly altered titles, and still others with different titles but the same storyline.

Just as B movies used to be turned out in ten days or less to capitalise on the success of A movies, so today made for television, steaming, or DVD movies are produced as clones. And just as some B movies are far better for being simpler and more direct than the bloated A movies they imitate so some of the straight to DVD movies are better than the big ego productions of Hollywood.

Consciously the author’s scope seems mainly the USA. There are few references to England, apart from H. G. Wells as above, and less still to films originating in other parts of the world. There is no mention of the Mars mission portrayed in ‘Murder in Space’ (1985) from Canada. It may be that the paucity represents reality and if so, that itself might have borne comment. Why are Americans more fascinated with Mars than others.

Miller ridicules many critics who pan movies. His suspicion is that many critics have to earn their spurs by being negative, and so will deride a movie on flimsy ground. And once a major critic does this, the herd follows in the tracks of the bigger beast. Really? Would self-respecting professional film critics for such prestigious mastheads as the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Colliers, and so on be that lazy, arrogant, and stupid. Really!

Can there be evidence for such cartels? Miller lists in chronological order nearly word-for-word repetitions in reviews from dozens of critics, one repeating the other, it would seem, unless there is a mighty busy god of serendipity. He even shows how mistakes in the first major review, say a typo in a character name, are reiterated in the flock that follows. Amen, Brother Thomas, lay on the wood.

What is surprising are the times – two are documented in these pages – when a producer dams his own film as it goes on release. This damnation may be explicit or implicit, and perhaps represents some corporate pathology being played out in public. Yes, dear viewer, even the snow white Disney Corporation has been known to denigrate its own product.

Less informative is Miller’s fascination with the opening credits of movies. He cannot fathom why critics do not comment on the scene-setting effect of opening credits, citing some examples of very effective opening credits, like those of the 1953 ‘War of the Worlds’ and some very ineffective ones. Point taken. He then repeats the exercise. He then refers to it again, and again. And reverts to it at the end. I believe him when he says he sometimes puts in a DVD and watches only the opening credits before moving on to something else. I also believe him when he says his wife finds that annoying.

Did I say Nerdboy above, or what.

Another of his pet peeves which gets ground into the eyeballs by repetition is the lag in communication back and forth between Mars and Earth. He nails this of course, but then pounds it in and in and in. Yet at the same time he waxes lyrical about a completely inaccurate and anti-scientific account of Mars, including sunbathing, of ‘Robinson Crusoe on Mars’ (1964), discussed elsewhere on this blog. Instantaneous interplanetary communication will condemn a movie to the sin bin in his eyes, but sunbathing on Mars with a monkey will not. Go figure.

Category: Book Review

‘Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science’ (2017) by Karl Sigmund.

GoodReads meta-data is 480 pages, rated 4.17 by 107 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction.

Verdict: Only for the cognoscenti.

The Wiener Kreis was one of the engines of Twentieth Century science, including philosophy and mathematics. It began as a loose discussion group and evolved into a more tightly knit and organised group with satellites. The Kreis – Circle – waxed and waned with the circumstances and fortunes of its members until reality kicked in the door in 1938.

Those associated with it comprised a Who’s Who of intellect, e.g., Albert Einstein, Kurt Gödel, Hans Reichenbach, Carl Hempel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap, Richard von Mises, Karl Menger, Moritz Schlick, Ernst Mach, and more. Chaps all if it has to be said. Bertrand Russell and other English-speaking intellectuals beat a path to its door. As a whole the Kreis published monographs and the journal ‘Erkenntnis’ (Knowledge). Springer continues to publish it to this day.

Its members together offered logical empiricism though many preferred to say logical positivism, because the empiricism was made of air. It was the big bang that created analytic philosophy that dominated English-speaking philosophy in the Twentieth Century. Its exemplars include A. J. Ayer, Hans Kelsen, Karl Popper, Willard Quine, Frank Ramsay, and Lord Russell himself and all who followed his star.

They were united in a holus bolus rejection of metaphysics and often suspected one another of just that tendency. Some of the descriptions of seminars sound rather like Communist Party cell self-criticism sessions. Of course, there were many intellectual differences among the members. This book also gives weight to their personal and social similarities and differences. Many were Jewish and that made life increasing difficult for them and those around them in Mitteleuropa.

Many of these folk were oddballs, indeed, but the Emperor of Strange had to be Ludwig Wittgenstein who has sometimes been worshipped as a saint in philosophy and at other time derogated as the selfish malcontent that he was. Whoops, my objectivity slipped on that one.

Heir to a vast fortune, he lived like a vagrant. Some find that admirable. He was perhaps born to be a stylite. (Look it up.) He did not use the fortune to any good purpose and in time much of it was seized by the Naziis for their purposes. Even so he always had money available though he seldom spent it.

When acolytes appealed to him for financial help, he dismissed them on the ground that poverty was ennobling. Thanks, Ludi, they all said with a smile. Some of these appeals came from very desperate people, sometimes Jews who had been his students, in the 1930s. There is no record that he ever did anything to help another person. This saint attended only his own soul. He also managed to ruin the careers of more than one acolyte, but that is too complicated to explain here.

The times were indeed demented as illustrated in the case of one of the more sober and sane members, Moritz Schlick, who ran the show for years. A disaffected student blamed Schlick for all his woes and festered on this belief for years, sending him threatening letters, stalking him, accosting him on the street. The forbearing Schlick endured this burden for some time until finally he reported it to the police. Once the police became involved the student blamed Schlick even more for his troubles.

Now get this. The student got a gun and tried to shoot Schlick. He bungled it and was arrested, founded insane, and locked up….for eighteen months when he was released. Got another gun, and tried again. Another bungle. Arrested again. Locked up again. Released again. Got another gun, and third time successful. If that reads like a bad plot, sit down, because it gets worse.

The murderer was tried and sentenced but by this time time no one cared. He served a few years in a prison and then was released whereupon he became an ardent Nazi and later served as a guard in a death camp for Jews. After the war he was whitewashed, as were so many Austrians. In Germany a German with that record would have been barred from public service. Not so in Austria. (Indeed some Germans relocated to Austria because of that difference.)

He became a post-war bureaucrat, prospered, and retired on a state pension. When a biographer of Schlick wrote that he had been murdered by a deranged student without giving his name, the murderer sued for libel and won. It sound like something that Fox News would do today. The dead victim became of the villain and the villain became the victim!

One of the most attractive figures in the constellation of the Vienna Circle was Otto Neurath, and we pay tribute to him most days. Go to a public men’s room and on the door is a pictograph representing a man. Pointing the way to the train station is a picture of a train engine, not a letter T. A sign indicating a traffic turning-lane shows a car over a curved arrow. Look at the pictorial icons on the smartphone screen. These are downwind traces of Big Otto. Having given up on Esperanto, he tried to create a pictograph language with 800 words and a grammar of isotypes. Big Otto worked closely with his wife Marie on this. She was one of the few woman around the Circle. His personal and often repeated motto was ‘We must improvise.’ The more so they did when on the run from the Naziis.

While these thinkers argued to the death over protocol sentences and other esoteria, the world around them caught fire and took some of them completely by surprise, while others had seen it coming and fled. They spread the seed of logical positivism far and wide in the English-speaking world, though at the end of the war Austria did not want them back. Rather it preferred to appoint and promote people like Schlick’s murderer. The example is the effort made to block Kurt Gödel’s return to Vienna. Grotesque but true. Austrian university authorities went to great lengths to insure he did not return to Vienna. Yet every mathematician in the world — apart from those in Austria — regarded him as THE Genius of the ages.

Karl Sigmund near the building where the circlers circled.

Karl Sigmund near the building where the circlers circled.

I went to Grad School because I wanted to study Plato and Aristotle and their kind. Instead, I got ‘Language, Truth, and Logic’ and other such tomes. Through five years of graduate work I never did read Plato for a seminar. But Ayer, Russell, Popper, Hemple, Quine, and [see above]. Looking back on it, it was a form of discipline, rather like learning a dead language (Latin or Greek), in which form triumphed over content, process over product. It was a time when philosophers and hence we cousins in political theory were trying to be scientific.

The PhD was the hardest thing I have ever done. The coursework was hard. The oral exams were hard. Writing the dissertation was hard. The defence was hard. It was all hard. It’s been downhill since!

I listened to this book on Audible and found it entertaining though some of the expositions were hard to follow. The reading is most accomplished. The difficulty was following the abstract and abstruse thoughts without seeing the words.

‘The Adventures of the Busts of Eva Perón’ (2015) by Carlos Gamerro

Good Reads meta-data is 352 pages, rated 3.71 by 51 litizens.

A tale of corporate ambition set against Montoneros terrorism in Buenos Aires Argentina. Our hero Ernesto Marroné is determined to rise to the top. He studies self-help books, listens to motivational tapes, memorises the nostrums of career guides, has read every book on management there is, always smiles on the outside, and gets to work before anyone else. The only way is up!

Then….the Montoneros kidnap the head of his firm, and they send one of the victim’s fingers to the firm as proof, with their first demand: that a bust of Eva Perón be displayed in each of the firm’s ninety-two offices within ten days! The task of complying with this demand is assigned to the ever-ready, corporate yes-man Marroné.

As he places the order at a plaster works, it is seized by striking workers and he is made captive. He tries to use his ‘How to Win Friends and Influence People’ wisdom to cope. He has a veritable bibliography of such books in his mind and he takes pages from many of them to apply to his situation. The chief title is ‘Don Quixote: The Executive-Errant,’ fitting for this picturesque novel of adventures down the rabbit hole. Some of that is downright hilarious. Some of it is downright depressing. Most of it is just boring.

Even more amusing is his effort to abstract from the titular lady herself insights that can be used in this situation. He mentally composes an ‘Eva Perón on Management’ book starting with how to manage striking workers. The clean-cut, über bourgeoise Ernesto becomes a leader of the strike, and in so doing learns a great deal about Argentina and Argentines that he did not know before. He comes to identify himself with Eva.

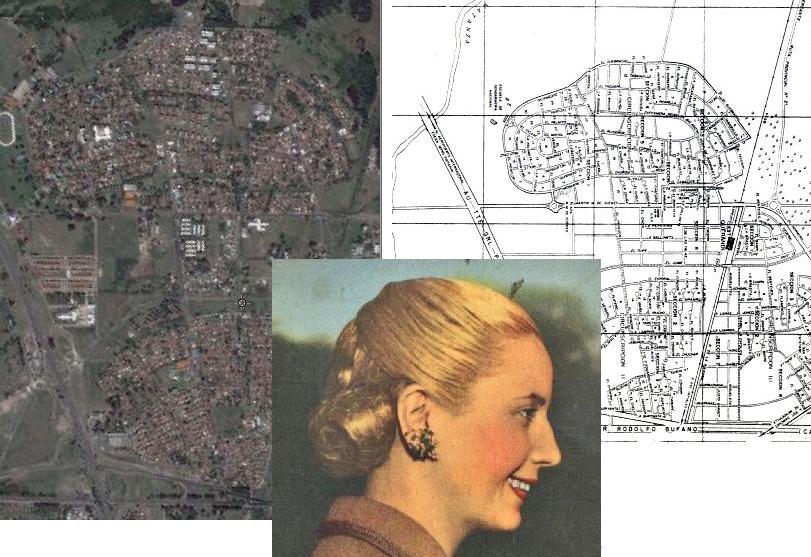

As a leader the workers he goes hither and thither in the slums, barrios, and suburbs, and finds his way to Evita City. Yes, in 1947 President Juan Perón had a suburb named for her and its borders drawn to resemble her profile. Illustrated below.

It still exists, though over the years the name has come and gone and profile has been lost. In it all of social services and amenities that Eva campaigned for were to be available to those fortunate enough to live there. Not so any more.

In its way the book is another tribute to the hold that Eva Perón retains over the imagination in Argentina.

‘A Concise History of Austria’ ( 2007 ) by Steven Beller

GoodReads meta-data is 334 pages, rated 3.7 by 52 litizens

Homework for a proposed trip to Vienna next year.

This is part of series of concise histories.

This is part of series of concise histories.

History is just one thing after another, and in the case of Austria, the things occur here, there, and everywhere.

The book concludes with an outstanding summary of the paradoxes that comprise Austria today. In brief, the greatest Austrian is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who was born and raised in Salzburg when it was not part of anything Austrian and he never thought of himself as Austrian. See David Weiss’s ‘The Assassination of Mozart’ (1971) for melodramatic account of just how un-Austrian Mozart was. I read this title long ago.

Austria came to exist as lines on a map at the end of World War I, then it disappeared in the Anschluss (which despite ‘The Sound of Music’ was much desired by most living within those lines), and then reappeared as another set of dotted lines in 1945.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire (AHE hereinafter) developed from the vestigial Holy Roman Empire and the Hapsburg dynasty. The latter at one time included Spain, the Netherlands, and much of central Europe in today’s Austria and Hungary and as far south as Bosnia. The Holy Roman Empire is even harder to pin down. Its emperor was selected by German princelings, though Prussia – the most significant German-speaking land – was not included. Got it so far?

The AHE was polyglot, multi-lingual, scattered, variegated, poly-national, and changeable.

Yet in its core it was German with a considerable and influential cosmopolitan Jewish population in Vienna. When it stumbled into the Great War, it was in fact trying to avoid war, but being inept, instead it precipitated it. Most of the dozen ethnic nationalities in the AHE wanted no part of Vienna’s war and withheld men, material, and food. By 1916 Germany had taken over the AHE in all but name, managing its finances, commanding its armies (in Italy, Romania, and Russia), running the trains, distributing food, and directing the home front. The war was a chemical bath that dissolved the AHE long before the Treaty of Versailles made it official.

The move for German-speaking Austrians to join Germany, even after the latter’s humiliating defeating of 1918, was so widespread and strong that the League of Nations forbade plebiscites on the question of Anschluss. Uniting Austria with Germany would have enlarged and strengthened Germany at a time when the League, i.e., is France, wanted to weaken it. Instead the League fostered the creation of something that have never before existed: Austria, a nation-state.

It consisted of a hinterland and Vienna, and the two had little in common. While Vienna had long depended on Hungarian grain, Czech manufactured goods, and Slovene timber, it had little truck with the new hinterlands attached to it. Some like Salzburg were altogether new additions.

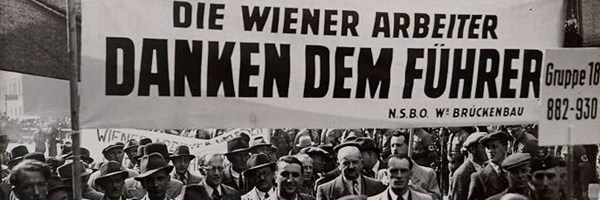

The Depression hit Austria like a hurricane. As Hitler’s Germany rose from the ashes it was the light on the hill for Austrians, and now more than ever they wanted Anschluss, partly to escape the penury of the times, but also to reclaim its own Germanic essence, and to reject the cosmopolitanism of Red Vienna (where communists, socialists, social democrats, Jews, and liberals busily undermined each other).

When the producers of ‘The Sound of Music’ asked Austrian authorities for permission to stage a parade simulating the Nazi German entry into Austria, they were refused. Why? Because Austrians hate Naziism so much that even today the sight of such a parade would ignite a terrible reaction which the authorities might be unable to control. Oh, replied the producers, in that case they would use the ample newsreel footage of the rapturous welcome Austrian gave Nazis in 1938. Ah, replied the authorities, here is the permit for the staging.

It makes depressing reading to see how eagerly Austrians joined Naziism in all of its worst deeds. The enthusiastic enlistments in the SS. The ready subservience to the Gestapo. The quick denunciation of Jews. The vigorous competition to host and staff death camps.

Figure it out.

Figure it out.

Before 1938 there were more than 100,000 Jews in Vienna, perhaps 1000 survived by 1945.

Austria and Austrians were willing allies of Germany. Whereas Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and others were bullied and cowed into the Axis camp, Austria entered to the sound of music.

Yet in the 1943 Moscow statement, sometimes called the Treaty of Moscow, the Allies said Austria was the first victim of Naziism. Huh? That has never made sense to me, and even less so as I read the litany of its crimes with Naziism in these pages. But now I see the point.

It was one instance of a broader Allied strategy to prise Germany’s partners away for it by implying they would be treated differently. In this spirit when Italy changed government in 1943, it was readily accepted by the Western Allies. Likewise for years FDR kept lines open to Vichy France to dampen its enthusiasm for Naziism. Abraham Lincoln tried the some thing throughout the Civil War, trying to woo individual southern states, like North Carolina, away from the Confederacy with some success.

Stalin went along with this terminology for his own reasons, namely, if it didn’t suit him later, he would renounce it as fake news.

Abracadabra! In 1945 Austria left its Nazi past behind. It was occupied by the Allies until 1955 but the de-Nazification process there was perfunctory from the beginning. See ‘The Third Man’ (1949) by Graham Greene. In fact, it became a route for Naziis to get to the Adriatic and escape. Schools, hospitals, railways, manufacturers and others were ordered to destroy the records for the period 1938-1945. Others did so on their own initiative. The Brown Years were erased and blurred and a national amnesia settled over the new lines on the map.

During the post-war Occupation, the Marshall Plan poured money into the western part of Austria, while Russia stripped the Eastern part of everything from heavy machinery, to concrete blocks from buildings, to clothing, and dried food. The wire from concentration camps was taken down, baled, and transported to the Soviet Union where it was used in the Gulag. So effective was this scraping of the earth that by 1955 there was nothing left to take. Then the dotted lines became solid as a new Austria emerged from the cocoon of occupation.

But by 1955 a neutral Austria suited both the Western and Eastern blocs. There came the Austria we know today. For all of its superficial worldliness manifested in Vienna in particular, it is inward looking, reluctant to change, intolerant, industrious, frugal, and insecure, says the author.

I saw Kurt Waldheim speak in 1986 and he denounced foreigners, insofar as I understood the German. That was in Salzburg, a place that became Austrian by drawing lines on a map, whose major claim to fame is a festival which originated in the desire to reject modernity. The lederhosen of tourism in Austria was a way to cling to its (fictional) past and avoid modern life with trade unions, urban life, women’s liberation, unruly students, the interaction of nationalities (Jews), international influences, protestants, and so on.

When the Berlin Wall fell, Austria shrank from engagement with its historic affiliations in the East, and only diplomatic pressure – greased by German marks – and deft handling by some Austrian leaders overcame that reluctance to admit reality. Yes, Austria had taken in 150,000 fleeing the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, but only on the understanding that they would move on further west. Ditto another 100,000 after the Prague Spring in 1968. These were experiences few Austrians wanted to repeated in the 1990s.

Steven Beller has many other titles.

Steven Beller has many other titles.

While in Salzburg I heard an Austrian politician talk about the Brown Years of Hitler. One thing he said made perfect sense. We were disunited among ourselves, that is, even that minority who opposed Anschluss mostly argued against each other. After the war, the new Austrians of the new Austria closed ranks against all outsiders, and for these new people everyone else was an outsider, including even Austrian expatriates, Austrian Jews, and Austrians who were not German by language or Catholics by religion.

My next reading assignment is ‘Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science’ (2017) by Karl Sigmund.

When I went to Salzburg in 1986 I read Carl Schorske’s ‘Fin de Siecle Vienna’ (1980) and William Johnston, ‘The Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History, 1848-1938’ (1972). I tried and failed to read Robert Musil’s ‘The Man without Qualities’ (1930). Not inclined to try again.

‘Santa Evita’ (1997) by Tomás Eloy Martínez

Genre: Fiction

GoodReads meta-data is 416 pages, rated 3.8/5 from 1573 litizens.

Verdict: Quite a ride. Best to have a scorecard of the names and places.

The novel offers an examination of the place of Eva Perón (1919-1952) in the soul of Argentina and Argentines. Eva is dead. Long live Evita!

While there are retrospective glimpses of young Eva growing up, meeting and marrying Juan Perón and ruling with him, and her earlier career on radio and in films, most of the book concerns her afterlife.

When she died Perón went through the stages of grief, culminating in the plan to build a giant mausoleum to her memory. Barely had the ground been cleared in central Buenos Aires for the building when Perón was toppled in yet another military coup. (For what it is worth he won the popular vote in three elections.)

The plotters were at odds among themselves in every way but united in one. Above all else every trace of the Peróns, both of them, had to be erased immediately, least their followers, who were undoubtedly the majority of the populace, rally to the remaining symbols. Street signs, building names, charitable foundations, orphanages, schools that bore the name Perón, all of these had to go. Over night school teachers were required to mark out their names in every scrap of instructional material. Republicans have been doing likewise regarding Obama.

The youthful Eva.

The youthful Eva.

No symbol of Perónism was more important than Eva herself. At her death Perón had set about having her mummified like Lenin and to be put in a glass sarcophagus on display to the faithful. He had seen the thousands come to mourn her as she lay in state, and since there was demand he set about supplying it. Work had begun on that. There was also a nascent plan to produce wax replicas, least the body decay despite the preservation. Remember Jeremy Bentham?

She spoke.

She spoke.

They listened.

They listened.

They came; she gave.

They came; she gave.

Even the touch was enough.

Even the touch was enough.

Some of this work of preservation had been done in secret and later amid the turmoil of the coup which was followed by an in-house palace revolution by another faction. Moreover some of those trusted with the cadaver tried to hide it from the usurpers. When usurpers found it, they in their turn tried to hide it. In short, the body got lost for many months. When it was discovered the new regime was in a quandary about what to do with it. Unsure even if it was the real thing. More hiding followed.

To desecrate it would call down the wraith of the Catholic faithful and the electoral majority of Perónistas. To bury it would create a site of Perón pilgrimage. To hide it indefinitely in a time of coup and counter-coup would not suffice. To comply with Perón’s plea from his roaming exile to send the body to him would put a potent symbol at his disposal.

From these chemicals Eloy Martínez compounds quite a story as he enters into the minds and souls of the morticians, embalmers, army officers and soldiers, on-lookers, janitors, true believers, by-standers, journalists, and foreign diplomats who come into contact with the mystery train transporting the cadaver or one of its several replicas.

To summarise what cannot be summarised, thinking takes time and initially during the thinking time a squad and a colonel, low enough in rank that he could not reject the assignment, drive the cadaver in a coffin around in a truck from place to place, phoning in for more orders. This becomes a truck of Otranto as the six men keep to themselves, park in deserted streets, eat army rations, skirt cemeteries, and begin to think Santa Eva is watching them from the coffin they transport, the coffin which they must not open, but which…

When the truck is parked overnight, and a careful watch is set, yet the next morning the truck is surrounded by flowers. Or when they turn into a blind alley far off the beaten track to park for the night, when they open the doors to get out they find the alley is now illuminated with candles. Spooky. Thereafter the colonel is obsessed by the body.

Meanwhile, others took charge of her personal effects and papers and in pawing through them come into vicarious contact with the Argentines she touched. There is no doubt that she was a miraculous saint to millions, one who brought material succour and, more importantly, spiritual hope. It is all there in the letters she received from individuals and the letters she sent in reply. This is charisma.

In death there are sightings of her in the valleys, pampas, deserts, villages, barrios, hills of Argentina. The rumours spread. Since there are no facts to contain the imagination, the rumours grew. If a sighting was reported in a village in the distant mountains, within a few hours a host of peasants was on the road making for that village. If a bundle of cash was bestowed anonymously on an orphanage the dead hand of Eva was credited. When the national soccer team scores a goal against the odds ….., and so on.

Dead Eva Perón was beyond price and dangerous beyond measure. Dead she was omnipresent and omnipotent.

The replicas are as dangerous and priceless as the cadaver and in the hysteria, miasma, fear, exhaustion, and confusion of the time, those responsible for the replicas and the cadaver themsevles become uncertain about which is which.

The novel is set out as the author’s report on his effort to write a book on this subject, and some of it takes the form of interviews years later with participants or their relatives, or the discovery of diaries kept by participants, old newspaper cuttings from villages in Tierra del Fuego, letters and documents as officials pass the buck, censored television footage, interview transcripts from the time, radio tapes, and so on. Much is fact, most is fiction.

At time the author breaks the theatrical fourth wall and addresses the reader directly. He also passes comment, droll and disparaging on Andrew Lloyd Weber’s abomination. Likewise he makes short shrift of Juan Luis Borges attempt to crucify Eva.

The grip the woman had on the soul of Argentina and Argentines is the theme. And that grip included both those who loved her in their millions and those who hated her in their millions. Together these millions were as one in their complete preoccupation with THAT WOMAN. Both get plenty of space in these pages.

Tomás Eloy Martínez

Tomás Eloy Martínez

I seem to have had a Perón spree, starting with Joseph Page, ‘Perón: A Biography’ (1983) and then Eloy Martínez’s ‘The Perón Novel’ (1999), both reviewed elsewhere on this blog, and now this. Eva is much present in these two titles, but I wanted to read more. I did watch the A&E biography on You Tube, which was basic but not as bad as some of the illiterate comments say. Then we were given tickets to see ‘Evita’ later in the year and I decided to do some homework on Eva, starting with this one. I have one more to go, ‘The Adventures of the Busts of Eva Perón’ (2004) by Carolos Gamerro.

I read Jeane Kirkpatrick’s ‘The Perónist Movement in Argentina’ (1971) in graduate school and it left me with a curiosity about Argentina. What she argued was that historically the army made Argentina and that despite its many later corruptions and failings it remained the only legitimate institution in the society. ‘Legitimate’ means being accepted by the populace.

When I referred to a scorecard above the meaning is that it helps to know the players, some of whom I have learned of through the reading above. To read it based on Lloyd Weber, well don’t bother.

Every military coup in Argentina was justified on the ground that it would bring stability. A coup was followed by a counter-coup in one case by a single day and in another by a month. No military government lasted as long as the term of an elected government. Civilian governments, said the army officers, were unstable. The duty of the army was to bring stability. This it did in an endless parade of coups and counter-coups, sometimes between the services, Navy, Air Force, and Army, and sometimes within the Army. They shot it out, bombed Buenos Aires, and fought it out again and again. Stability is a hard thing to get out of a gun.

‘Indignation’ (2008) by Philip Roth.

…. in which an immature boy from New Jersey goes to college in Winesburg Ohio. He makes few friends and falls in lust. It is 1950 and when he is expelled, then he is drafted and dies in Korea.

Meta-data from Good Reads is 3.7/5 from 11959 litizens.

Verdict: Ah, now I remember why I do not read novels by Philip Roth.

Our hero is Messner who dislikes other Jews he meets in Ohio, cannot get along with Gentiles who befriend him, and is attracted and repelled by the only co-ed who knows he exists. With the auto-didacticism of youth he spouts ill digested bon mots from Bertrand Russell.

On the one hand he is typical of a nineteen-year old in all this and on the other he has not got the sense to stop. His self-destructive streak has no rhyme or reason but the needs of the author to make him and vicariously himself (the author) into a victim. Young men are often as stupid as Messner but they grow up little-by-little but not so here in either case.

HIs expulsion arises in this way. He hates attending Chapel, not on religious grounds, but because it is boring. He hires a substitute to go in his place. This fact is revealed by one of the many people he antagonises and when confronted with the fact he is defiant. Expulsion follows.

(I attended Chapel in a similar fashion and found it often boring, but not always. It was sometimes an opportunity for rest, if not reflection. At other times I heard Basil Rathbone read Shakespeare, Robert Penn Warren recite poetry, Ernie Chambers call blacks to arms, Sarah Gardner make science wonderful, Alexander Kerensky mourn the missed opportunities of 1917, Paul Tillich bring the New Testament to life, and a stage set designer whose name has been lost talk about how to stage Greek tragedy in a contemporary theatre, and more that I can no longer remember. More’s the pity. Thereafter with new eyes I saw Shakespeare, read ‘All the King’s Men,’ followed Senator Chambers’s career, found Tillich in utopia, and watched Sophocles.)

It is the usual from Philip Roth, to my mind ever an greying instance of arrested development. He is totally focused on his ….. first friend. He and Silvio Berlusconi are cut from the same cloth. Neither Messner, the paper protagonist, nor Roth, the writer, shows any interest in Olivia, the co-ed, except insofar as she relates to his first friend.

The style is simple and that is a relief as the pages are free from the lengthy and pointless descriptions that encrust other of his novels which I have sampled. Ergo it is easy to read. The style, one supposes, is to match the voice of the man-boy Messner. In that it succeeds.

The title is ironic. Throughout Messner, transfixed by the Korean War, recites a phrase from the People’s Republic of China’s national anthem long before it entered the war. In Korea at a map reference he is killed by Chinese, we must suppose. That all goes beyond heavy-handed to lead-handed. There is never any explanation of how and why Messner has latched onto this passage. It is just the author’s vanity intruding. Did I mention that Messner was dead all along. I did not much care. Not true, I did not care at all.

Here is a comparison. This Messner is about the same age as William Styron when he wrote ‘Lie Down in Darkness’ (1951) at the time ‘Indignation’ is set. ‘Lie Down in Darkness’ is a tour de force novel. Friends of Roth, parading as critics, say ‘Indignation’ is a character study. Ha! ‘Lie Down in Darkness’ is a trip into mental illness that is exhilarating, compelling, and frightening. By the way Styron was a Marine and his take on the Korean War is in ‘The Long March’ (1954).

The setting must have been a deliberate reference to Sherwood Anderson’s ‘Winesburg’ (1919) which is a series of short stories that together present the inhabitants of a Winesburg Ohio. Anderson’s prose is supple and evocative. The people come to life off the page. A reader feels the breeze from the river and hears the quiet sobs from behind closed windows with a minimum of words. It is no wonder that the young William Faulkner sat at Anderson’s feet.

Philip Roth

Philip Roth

I found Roth’s novel boring and cold. I persisted to honour the gift it was from a friend.

The novel was filmed in 2016. Go for it but don’t say there was no warning.

‘109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos’ (2006) by Jennet Conant.

Good Reads meta-data Rating: 4 from 1,234 votes. 425 pages.

Verdict: not the biography of Oppenheimer I was looking for.

The development of Atomic Bomb in twenty-seven months on a mesa in New Mexico is quite a story from theory to practice.

The book offers a near day-by-day account mostly of the administrivia of Los Alamos. Largely told through the subsequent recollections of the office manager of the project, located at 109 East Palace Street in Santa Fe, Dorothy McKibben, who adored Oppenheimer. In silence the author credits Dorothy with a remarkable and flawless memory for conversations because she recalled them years later without the benefit of diary or any other written record from the time.

Only 40% of the way through the book did this reader notice any discussion of the engineering, technical, and scientific endeavours. Apart from listening to complaints about laundry and indulging the pranks of immature minds, Oppenheimer never comes into focus in these pages despite his image on the cover and his name in the title.

These impressions are not helped by the slangy style of exposition and the credulity of the author who takes as fact whatever a favoured source said. This reader got no sense that any assertions were double checked. In addition, facts were scarce. I never did get an idea how big the operation was. Only more than half way through are some numbers mentioned, e.g., 3,000 but given the one-eyed perspective of the author I was unsure who was included in that number.

I said one-eyed because the author is always on the side of the scientists, say when they complained about secrecy and security and seems repeatedly to belittle both the GIs who built most of the set-up and the intelligence agents who censored the mail, kept strangers away, demanded to see passes, and so on.

The immaturity of many of the scientists involved is breath-taking, the more so later when some of the same individuals took it upon themselves later to pontificate about the use of the Bomb. Even the fraternity brothers paled at some of their antics. While some of these draft-exempt scientists were planning panty-raids, in 1944 the Pentagon was sending 2000 yellow telegrams a day to mothers and wives.

Most of the Europeans on the project were more serious because Naziism was a reality to them, and not a newsreel. Indeed so focused were they on Germany that when the war ended in Europe many wanted to quit the project. They had so quarrel with Japan since it had no bomb and no prospect of one. Their goal was to get to the Bomb before the Naziis did.

At this point Oppenheimer was, it seems, crucial in motivating them to work ever harder, far from quitting. That he did this is, however, not explained by anything in his nature or character developed earlier in the book. Yet it was certainly crucial and he was the one who did it. We did get earlier the grudging admission by one of his many critics that Oppenheimer, despite his dilettantish pre-war mien, had proven adept at getting all those (egotistical) scientists to talk to each other. No mean feat that. More exposition of how that was managed would be welcome.

There are many assertions that Oppenheimer was attractive to women, that he had blue eyes, and a confident manner. So what? There are many of these and none of them built the bomb. There had to be more than these superficial descriptions to explain his singular achievements as noted in the paragraph above. Using the word ‘charisma’ is neither analysis nor explanation.

Oppenheimer is the centre of the book, even if he is seldom on the page. His own disregard of security is numbing. Why did he do those things that later would look so damning? My own conclusion is hubris. In the first instance Oppenheimer was sure, because he was so much smarter than everyone else, he would never make a mistake and give anything away, no matter to whom he talked. Second, he was likewise sure he would always be able to talk his way out of suspicion. So he thought.

Instead he simply called attention to himself again and again, and it stuck. And he created a pattern that was at best reckless and at worst sinister.

That a skilled intelligence agent could learn much from what is not said, or from the lies told, these are tricks of the spy trade that Oppenheimer never considered, since his hubris meant he never thought anyone else could out think him.

His hubris had another strand. After the war, he could have gone back to Cal and time might have healed some of the wounds, but instead he haunted Washington, putting himself forward as Mr. Atom, advocating committees, and himself as a member. He was hard to miss. He had come to view himself as indispensable. Maybe he was, but the effect, given the two strands already mentioned, was to make himself into a target. He seems always to think he was an invulnerable Achilles.

While the author mocks the efforts of the security officers with the fact that they missed Klaus Fuchs, who was indeed passing information to Them, she seems to fail to see that the security officers were right. There were leaks. Fuchs, by the way, was not the only source of leaks but the most well placed.

Nor does the author indicate any effort at ascertaining, say by visiting the National Archives, whether German agents were active in the matter. Still less other Soviet agents who monitored Oppenheimer when he was away, as was often, from Los Alamos.

The drama accelerates quickly in the middle of the book, and we read less about bickering, picnicking, and laundry, when it is time to test Trinity.

The Trinity test at 10 seconds after detonation.

The Trinity test at 10 seconds after detonation.

Though here, as always, is a squabble about the name which is dutifully recorded by the author.

Yet she sits on the fence about the use of the bomb. She quotes estimates of causalities of the projected November 1946 invasion of Japan and then in a rare footnote says this figure might have been fabricated. That is quite an accusation to make in a throwaway footnote. It is a fact, by the way, that the Pentagon planners had begun preparations for 500,000 American casualties from an invasion of Japan. It had also contracted for 10,000 yellow telegrams a day.

What president would not use the bomb in preference to such a toll?

Given the many uncertainties involved with the Bomb, the only way to go was to use it. Why? What demonstration would convince the Japanese? Blow up an uninhabited island? Not likely to be convincing. They would suspect a trick. That the Bomb would even work was always in doubt. If it did not work on the island, then it would serve no purpose but waste the weapon and do so in a way that nothing could be learned from the failure. And a failed demonstration would queer the pitch for another demonstration.

Moreover, the weapons grade uranium was so scarce and hard to use that wasting a Bomb on an island might mean another one was not available for some time. Furthermore transporting the Bomb to the Pacific was hard. The cruiser USS Indianapolis that delivered the first Bomb was sunk by a Japanese submarine a few days after completing that mission. (See ‘Jaws’ [1975] for confirmation.) Would the next ship transporting a bomb be sunk with it on board?

The prospect of besieging Japan into surrender was considered and rejected on many grounds. The Soviet Union would nibble away at Japanese weaknesses, while leaving the hard work to the United States. Little material support would come from a depleted England. The Chinese would turn full-time to fighting among themselves. During a prolonged siege the young, the women, and the civilians would suffer most as scarce resources would go to the defence forces. The result would be to cripple Japan for a generation or more without discrediting or displacing the war party.

Douglas McArthur always preferred manoeuvre and surprise to direct attacks, but he saw no other way in 1945.

The zealots in Japan were ready to fight on, and the example of Okinawa frightened everyone in the Pentagon. They would fight to the death unless the Emperor ordered them not to do so. To get to that order, the zealots had to be completely undermined. Hence the first big bang. It was made all the more dramatic for being a single aircraft. Japanese air defence spotted it but did not respond to its approach, assuming it was photographic reconnaissance.

In the two-day interval allowed for the Japanese to assess the destruction of Hiroshima, we now know what was unknown in D.C. at the time, that there was an abortive coup d’état, but it came to nothing. The second bomb, by the way, was not targeted on Nagasaki but bad weather took it there.

Back to the book in hand, the author seems to relish name dropping, as if everyone associated with a notable university is somehow a superior person. I could only put this down to an ingrained snobbery. This attitude shows also in the way those who were not blessed with such illustrious associations are portrayed. General Lesley Groves is one example. He, more often than not, is portrayed just one step away from Groucho Marx. Yet he oversaw an unprecedented and wide-spread effort of which Los Alamos was only a part, but he gets barely any credit, until, perhaps at the urging of editor, some condescending good words are applied toward the end. But overall the tone is, how could this nobody criticise these men from prestigious universities. Yes, Groves had an MIT degree, but he was but a student there, and in those days, by the way, MIT did not have the caché it does now, partly thanks to graduates like Groves.

Yet the text shows he was right about many things, like the irresponsibility of some of the scientists, about the need for secrecy, about the dubious nature of the undertaking, about the subsequent need to explain and justify everything done, and even the spies. More importantly, that he stuck by Oppenheimer as the right man for the job even though he did not like him.

The author has an admirable list of titles on related subjects.

So be it. Not for me. Reading this book but confirms my cynicism about the world of New York City publishing.

‘Circe’ (2018) by Madeline Miller

Good Reads meta-data is rating 4.4/5 from 10127 litizens. 352 pages.

Verdict? Marvellous.

Circe is a daughter of Helios, a Titan. Sounds better than it is.

The Greek world is full of gods in a bewildering array of statuses, ranks, powers, egos, and so on. Zeus defeated the Titans and most were destroyed in the Divine War. Only the most essential, like Helios, survived. He is one of the most important remaining Titans but no Titan is important among the Olympians. Over the eons he has sired many children. Every deity is important to mortals. Some are gods, some are demi-gods, some are titans, some are nymphs, some are mortals, some are half-animal, and so on and on. This is a family tree for the LDS to sort out.

The book is a biography of one such child, Circe. Though ageless and immortal, she changes over time from a sulking metaphorical teenager trying and failing to win the approval of her aloof father to become a witch with witch’s brews. She and Flavia, whose books are reviewed elsewhere on this blog, would make quite a pair.

While immature in her father’s house, she transgressed by giving wine to a suffering Prometheus before he was sent to Alcatraz. For this sin she was exiled to an island dot far away to pass eternity alone with pigs. Later clever Circe finds a way to blackmail Helios with her sin.

Over the centuries in this insular retreat she meets passers-by, and she learns of the mortal world from these experiences. For a time she is befriended by Hermes, though he does so only for his own amusement and when no longer amused he is no longer friend.

None of the echelons of the immortals will have anything to do with this outcast, apart from Hermes who is partly spying on her for Helios, and so she takes an interest in the mortals who find the shore. She welcomes some, careful to keep her yellow eyes concealed for they declare the godhead, and regrets it.

One betrays her trust. Another rapes her before she can utter a spell, but she takes revenge by increasing the population of the sty.

Thereafter, she is much more cautious. Then one day wily Odysseus comes and she finds she cannot, nor does she want to deceive this deceiver. What a fresh and vivid portrait of this marriage springs from the pages. Marvellous. Yes, the story is well known but this is a telling Homer would envy.

Finally he leaves, not knowing that she is bearing his child, a son. This is a circle that closes in the remainder of the book.

With the great learning that underlies the book, the author explains much. One example will suffice. Why are the gods so capricious with mortals? Think about it. If mortal life was easy, then mortals would have no reason to pray to the gods and make sacrifices. While the gods do not need these prayers and sacrifices in any material way, together these offerings are how the divinities establish status (along with their powers) among themselves. They are counters in the social snobbery of the Olympians, nothing more. But since the gods have no other pastime but that snobbery, it is the only game in town.

The worse the harvest, it follows there will be more the prayers and sacrifices. The more children and women who die in childbirth, the more the prayers and sacrifices. Of course, to keep the wheel spinning the gods must occasionally allow a good harvest, and for child and mother to survive birth. But only now and then when it pleases them. Sounds about how casinos work, come to think of it.

Odysseus did in time return to rocky Ithaca, but as with many a war veteran, the man who came back was not the one who went away. He is changed. That change is the dynamic of the latter part of the book. He returns short-tempered, easily bored, lustful, violent, and voting Republican. Yet in some ways he is what he always was. This schizoid duality makes sense in these pages. Penelope plays her part, too.

Madeline Miller

Madeline Miller

The author brings this world of the gods to life with razor sharp insights, exhilarating prose, penetrating details, and a profound compassion. Yet no punches are pulled. None. The violence rips the page. The arrogance of the gods burns the eye of the reader. The duplicity of mortals in this world is bottomless. All this is true, yet Circe delights in spring flowers and warm sand underfoot. Penelope abides. Telemachus is straight as an oak.

Her earlier book ‘The Song of Achilles’ is reviewed elsewhere on this blog with the same acclaim.

While pulling these remarks together I noticed a number of deprecating reviews, many of them video, by mouth-breathers (in Jim Rockford’s phrase). It was amusing to watch a couple of these pygmies.

Robert Hughes, ‘Barcelona’ (2011)

A self-indulgent memoir of time spent in Barcelona by the man with shag carpet for a typewriter, the rich, soft, deep pile of his prose remains but in this instance it is largely devoid of substance. Well, unless a reader must know where Hughes drank sangria in 1983. For that information, this is the book.

Ostensibly a guide to the city, it a scrap book to selective memory mainly confined to his personal experiences. However, to his credit, and unlike some, he does note in passing the deep and murderous divisions among Spaniards. Their many failed attempts to find a modus vivendi and Hughes labours under no illusions about the future.

But all in all, it is a very short and lazy book that seems to have been spoken into a recorder and then typed. Even the final chapters on Antoni Gaudi’s architecture, though showing signs of research done long ago, seem trip with neither destination nor arrival.

Robert Hughes

Robert Hughes

To sum up, it reads like the Fatigue of the Exhausted.

I chose it prior to a trip to Spain and to Barcelona but found it offered little of interest. He also has another, larger, book called ‘Barcelona’ (1993) to confuse readers.

‘Five Days in London, May 1940’ (1999) by John Lukacs

The momentous five days are May 24 to May 28 1940 when Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and overcame the resistance to his leadership within the War Cabinet and stiffened British resolve to resist Hitler and Naziism.

In so doing Churchill felt the pulse of the British people far more accurately than his many opponents, most gathered behind him in the Conservative Party. British resistance at the time of Dunkirk prevented Hitler from winning the war so that later American gold and Soviet corpses would win it.

These two paragraphs above sum up this book, the nature of which will be discussed at the end.

The story is without parallel. At age sixty-five Churchill became PM in the deepest crisis ever for Great Britain. His energy and concentration alone are noteworthy. His hour had come and he lived up to it. He was certainly the Greatest Britain.

First to the internal resistance. When Neville Chamberlain, over seventy himself stepped aside, after tumultuous scenes in parliament, he remained in the five-man War Cabinet, literally there was no one else at the starting line but Churchill. As PM he alone, it seemed, could restore order to Parliament which was elected in 1935 in far different circumstances. And many in the Conservative Party thought it best to let him try …. and fail, and then the real heir apparent could sweep up and take over. That was Edward Halifax (who had so many names and titles I gave up trying to keep track of them).

An aristocrat to the core, Halifax could not push himself forward but would wait to be called. He was, after all, a personal friend of the King, and a vastly experienced parliamentarian, diplomat, cosmopolitan, and more.

Why no one thought of calling new elections is not considered in this text.

As darkness grew with the fall of the Netherlands, the surrender of Belgium, the defeat in Norway, the collapse of France, the entry of Italy on Hitler’s side, the neutrality of the United States, Spanish troop movements near Gibraltar, the aggressive noise of Japan in Asia, the reluctance of Canada, many Brits wanted a truce with Germany.

While the British Expeditionary Force flailed, Churchill spent five days out-manoeuvring Halifax, Foreign Secretary in the War Cabinet, who kept on about a truce, a pause, an arrangement with Germany, brokered by France, by Belgium, by Italy, by the Duchy of Grand Fenwick. On and on he went in the super secret discussions, which remained secret at the time. According to the author, efforts were made subsequently by weeding archives to bury the secrets.

Halifax minced words, explored semantics, twisted meanings to find a way to open a mediated dialogue with Nazi Germany, anything to avoid another blood bath like World War I. He talked repeatedly with the Italian ambassador until Italy invaded France. He sought out informal intermediaries. He lunched with the King.

If there were a way to stop the war and guarantee Britain’s freedom by making concessions to the Naziis, Halifax wanted to discuss it. While nothing concrete remains on paper such an arrangement would involve leaving Europe to Nazi domination. Period. It might also involve emasculating Britain sufficiently so as not to pose a threat in the future to German domination of Europe by reducing the British fleet, by forcing it to withdraw from the Mediterranean and sacrifice Malta, Gibraltar, even Suez. Further it might involve disarmament, as it did for Vichy France in a few weeks. Would it also involve compliance with Nazi racial policies….starting with sending back refugees.

Churchill took the view from the start, albeit muted, that there was no point in trying to negotiate with Hitler. Either Hitler would propose impossible demands, or, if not, he would not keep his word. In either case for it to be known that Britain had begged for a separate peace on such terms would destroy British morale on the domestic front and comprise British standing on the international front with the Dominions and the United States.

The author makes a tenuous distinction between public opinion and popular sentiment in the era. The former, public opinion, was formed by the intellectual classes in newspaper articles, letters to the editor, lectures, universities, BBC interviews, essays, and the like. The opinion leaders were fearful of Germany’s might and had little confidence in Britain’s ability to withstand it. As a consequence many in these ranks were Defeatist to one degree or another. Some were admirers of Hitler. A small number wore the black shirt of Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet of Ancoats (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980).

Popular sentiment in contrast was the silent majority of the day, largely working class, generally uneducated and unaware of the wider world, although a great many had served in World War I and the author seems to forget that. The author makes extensive use of reports from the Mass Observation Survey, begun in 1935, as a window on to this stratum. These reports were qualitative surveys of doorstop interviews, pub conversations, overheard remarks on buses, talk in queues at the market, or discussions exiting cinemas. Unsystematic to be sure, but rich in detail. Yes, that is true but it is also true they were a lot more like gossip than systematic observations in the specimens I have read.

Popular sentiment was resolutely patriotic with none of the weakening cosmopolitanism of the intellectual classes. Germans were the Hun, not the progeny of Brahams, Beethoven, and Bach. It also had a rugged confidence in muddling through and took pride in that. They had once crossed the Siegfried Line and could do it again. This was the heart beat that Churchill felt, because he shared it, and which he mobilised.

While it is not emphasised Churchill’s mastery of the forms of British parliamentary democracy and cabinet government gave him an advantage. He timed meetings of the cabinet of thirty where he had many supporters, War Cabinet where he had none, parliament, BBC speeches, and personal meetings to create support and momentum for his commitment to war, war, and more war, and so to undermine Halifax’s position. In part his publicity campaign was to show to the United States and the Dominions that Britain would prevail.

While Dunkirk is mentioned, it is not the focus. In the foreground is the tactical conflict between Churchill and Halifax across the meeting table against the backdrop of the war. War Cabinet met two or three times a day.

For Halifax what was a stake in the war was the future of Britain. For Churchill what was at stake was Western Civilisation. It seems laughable to a jaded intellect today to say that, but that was both Churchill’s rhetoric and his perception. Naziism was a ravening and devouring beast that could not be caged, tamed, constrained, or reduced by negotiation and treaties. Even to try to treat with it was to become corrupted by its touch in one’s own eyes and in the eyes of the world. To plead with this beast from a position of weakness was suicidal. In a few weeks the French example would prove that point.

While Halifax evidently thought negotiation, even if it failed would enhance rather than diminish Britain’s claim to the moral high ground. It would show that Britain had done everything possible to avoid war. That almost makes sense, until considering the sacrifices that would have to be offered or made to a Nazi dominated Europe and Mediterranean. The willingness to bargain away the defeated countries (some of which had formal alliances with Britain, many of whose fleeing citizens had taken refuge in England) and those that might follow would never be forgotten nor forgiven.

He also differed from Halifax and his ilk in another way. He saw Naziism as the greatest evil and threat to Western Civilisation. Whereas Halifax and his kind feared Communism above all else, and many had earlier seen in Naziism a bulwark against the Red Tide, as earlier had many German nationalist, liberals, monarchists, bankers, musicians, and jurists who supported or tolerated Hitler at the outset.

The comparison has to be France, where nothing was ever secret and where the disputes within cabinet were blood thirsty. Every remark in cabinet was in the boulevard press within the hour. The conflicts between cabinet members were personal, religious, regional, and racial as well as ideological. Finally, the French generals gave up before the politicians. They were ready to surrender before Paul Reynaud, the last Prime Minister. Indeed Reynaud resigned rather than surrender.

Three things then distinguished Britain, secrecy, impersonal argument, and military resolve.

John Lukacs has a long list of impressive publications.

John Lukacs has a long list of impressive publications.

The book does not do the events justice. It treats Dunkirk and the decision-making about that as an annoyance to the cabinet machinations rather than central to it. It is replete with asides and ruminations that lead no where. Much of it is parsed in the negative, e.g., ‘he was not entirely wrong,’ ‘there is some truth in this matter,’ and so on. A manuscript like this submitted blind to a publisher today would be unlikely to be produced. ‘While the references to the Mass Observation reports are interesting, it is not convincing unless one is already convinced and then it confirms.’ That would be one of the many things an anonymous assessor might say.

I read it years ago and did not find it satisfactory but recent stimulation about Dunkirk brought it back to mind and I tried it again with the same result.