What is reality? What is not? What is the difference? Does it matter?

This is a novel from Finland, read in anticipation of a brief visit there later in 2016. It is charmingly enigmatic and low-key, rather reminding this reader of Finnish movies in those respects.

It is episodic, written in what might be diary entries of a young woman who, after graduating from university, goes to work in the editorial office of a publication called ‘The New Anomalist’ which is a one-man publication that prints only the weird and wondrous; two-headed sheep always get a good run.

Our nameless heroine tries to be nice to the oddballs and weirdos who contribute to the magazine, want to contribute to the magazine, or subscribe to it. Gradually, with constant exposure, they seem less weird and odd to her, and her own normal life seems illusory. Part of the explanation, for the literal minded, is in the title, but I took that mostly to be a metaphor for erosion of her own grasp on reality. Datura is an hallucinogenic.

Leena Krohon.

Leena Krohon.

While it is set in Helsinki that hardly matters. Mostly the encounters and rumination occur in the dreary one basement office of the magazine which could be anywhere. Ergo, no travelogue.

Category: Book Review

Alan Sillitoe, ‘The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner’ (1959)

This a collection of short stories that opens with the title story of Smith deliberately losing a race in order, as he sees it, to defy the authorities. Winning would have benefited him, but it would also have benefited the warden and jailers of the Borstal where he is held, and rather than do that he loses, and does so in a way that is obvious to viewers.

It told from his point of view and is hypnotic at points, especially during the fateful run. Once a reader starts, it draws one in.

Most of the stores have a common theme in loneliness. ‘Uncle Ernest’ is a touching story of a very lonely old man trying to befriend some innocent school girls, which is misunderstand by on-lookers. but who knows, maybe in time, Ernest might …. There is just enough ambiguity to make a reader wonder. No sledge hammer morals here.

‘Mr Raynor the School Teacher’ is another person trapped in his own, very small world, dealing with obstreperous boys, some of whom will find their way to the Borstal nearby. Meanwhile, he daydreams, but never dares speak his mind.

‘The Fishing Boat Picture’ is about love and sacrifice, but all clouded by the inability and unwillingness to communicate. Maybe the characters cannot say what they feel because they just do not know how to do so or they do not quite know what they do feel.

Alan Sillitoe at the time the book was published.

Alan Sillitoe at the time the book was published.

There are four other stories, suffice it to say. I enjoyed reading each of them. Though the petulance does wear thin. Sillitoe was one of the ‘Angry Young Men’ of British letters who found the post-war Welfare State inadequate.

We forget just how long it took Britain to recover from World War II, for example, in meat rationing, petrol scarcity, in employment. It did not enjoy the years of growth and plenty that the United States had during the Eisenhower years. One of the reason the decade of the Swinging Sixties was so liberating was because finally it heralded the end of this wartime privations, that had long ended in other English-speaking countries.

The Wikipedia entry on the story is convoluted and one-eyed, as well as pompous. But it has probably benefited editing twice since I looked at it ten minutes ago.

Tom Courteny in a still photograph from the 1962 film based closely on the titular story. I started to type that Courteny was born to play Smith, but then I thought the same about his performance as Ivan in ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970).’

Tom Courteny in a still photograph from the 1962 film based closely on the titular story. I started to type that Courteny was born to play Smith, but then I thought the same about his performance as Ivan in ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970).’

Another book that turned up during our move.

George Will, ‘A Nice Little Place on the North Side’ (2014)

William Butler Yeats wrote that ‘life is a long preparation for something that never happens.’ No, he was not thinking of the Chicago Cubs in a World Series, but it fits.

I omitted the subtitle: ‘History, Triumph, Mostly Defeat, and Incurable Hope at Wrigley Field.’

George Will has long been an expositor of baseball, well before Ken Burns discovered it. This book is an ode, spiced with some gritty reality, to Wrigley Field and those who have graced and disgraced it from zealous fans, first-ball throwing presidents, class and déclassé players, managers, and owners including the fabled P. K. Wrigley, famous for his indifference to baseball and his genius for marketing.

All of the lore is here reiterated: Babe Ruth calling the shot, Hack Wilson the perpetually hungover human fireplug, the storied Tinkers-Evers-Chance, smiling FDR throwing out the first ball, Ruth Ann Steinhagen shooting first baseman Eddie Waitkus (who had never met her before she pulled the trigger on him), Wrigley’s many innovations from Ladies’ Day to the ivy on the walls, and his decision to contribute the steel for light poles in 1941 to the war effort and the resulting, accidental, consecration of Wrigley Field as a cathedral to daytime baseball. Waitkus, by the way, was the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s novel ‘The Natural,’ ironic since Malamud had no interest in baseball, nor any knowledge of it either, as is apparent in the novel, somewhat emended by the screenwriter for the movie of the same name.

Did the Babe really call his shot? The record is far from clear, but the legend is indelible. Tinkers-Evers-Chance turned very few double plays but the journalist who said they did, created a reality that has endured despite the wizardry of sabermetrics. Will is very good at presenting a lot of facts, including statistical data, in digestible portions with spritely commentary, including the paltry number of double-plays this trio made in the year when they together ascended to myth.

Hack Wilson was certainly hungover on days when he blasted home runs. His drinking shortened his career and life dramatically. FDR and Chicago Mayor Anton Joseph (Tony) Cermak made an odd couple on opening day in 1933, and even more so a few weeks later in Miami when Cermak was murdered at FDR’s side, the speculation being that Cermak was the target of the Mafia as a warning to FDR to call off the IRS or to leave Prohibition alone, which had made them millionaires.

The end of live-ball era is much discussed, surprisingly, without much enlightenment. The rather mystical implication is that the live-ball ended with the advent of Great Depression. One catastrophe begat the other. Members of the pitching fraternity did not mourn the end of the live-ball era and celebrated the dead-ball era. I speak as a brother of this lodge.

The Olympian RBI totals Wilson and others compiled in the live-ball era endure, unlike most other records from the days of yore. Why is that? In those days most teams had but one big hitter who was preceded by yeomen who hit singles and were thus on base for the clean-up man. In those days before money-ball, pitchers threw strikes to such clean-up hitters and the RBIs followed. In subsequent years most teams have more, better hitters so there are just fewer ducks-on-the-pond when the sluggers pounds another home run. And pitchers are often instructed not to pitch to the big hitter when there are runners on base, even to the point of walking in runs. Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire hit phenomenal numbers of chemically-assisted home runs without threatening the RBI record.

Denizens of Wrigley Field have included the great and the good, the ordinary and the unknown, and the bad and the ugly. In the heyday of the aforementioned Prohibition Al Capone was a regular. Later Jack Ruby sold peanuts there before finding his way to a Dallas basement carpark a generation later. Ray Kroc had his first experiences at retail food in the concessions under the grandstand. And of course those indefatigable entrepreneurs the Bill Veecks (as in wreck, they always said) Senior and Junior.

While the leagues expanded and new stadia were built Wrigley Field, together with Fenway Park, remained testaments to the past. These new stadia seated tens of thousands, and came equipped with all mod cons, as the realtors say, from plasma television screens to beer on tap, cushioned seating, hot and cold running distractions, and more. They occupied vast tracts of land, sometimes seventy acres far out of town; the further out they went, the more parking they needed for fans to drive cars there; the more parking they needed; the further out they went. Some went so far out they no longer have a connection to any city like Foxboro in Massachusetts.

The needs of television to fill airtime and the need of the owners to sell fans more than a ticket once there, and the needs of fans to do more after driving hours to get there and back turned many such stadia into entertainment complexes. The distractions are many. One of the worst, and there are many contenders, are sound system that assault the senses, though thankfully being largely open spaces, never as excruciating as at NBA games. Being more expensive than the Apollo space program, these colossi have to multi-task, and this was integrated into their design: baseball, football, rock concerts, soccer, you-name-it, anything and everything.

The predictable result was that they do not suit any of them, least of all baseball, which is best played on Astro-dirt.

Wrigley Field stood apart from this pursuit of Baal for a generation or more, literally held together by chewing gum in more than one way. However, the balance sheet caught-up one day. Lights came. There followed a scoreboard that can be read by Apollo astronauts on the way to the moon.

Will deftly demonstrates that the fortunes of the Chicago Cubs who play (at) baseball in Wrigley Field are less important to fans than the price of beer. That price predicts attendance better than the team’s winning percentage (which the cognoscenti know seldom tops .500). The Cubs team has long been the lesser interest both to the ownership, the management, and the fans than the beer.

Will discreetly leaves the players out of this list those indifferent to the game itself. Though some of them did not evince much interest in the game while playing at it what with two errors by the same outfielder on one play in several games, six walks and a balk by a pitcher in one inning without a single out, ground balls lost in the sun, outfielders charging balls hit over their heads, one batter called out on strikes without a swing of the bat a record number of consecutive times, infielders unaware of the location of the ground when it came to ground balls, players traded…for themselves with a cash refund. All of which makes the achievements of some individuals all the more remarkable, like Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks, Bill ‘Sweet’ William(s), Ferguson Jenkins, Ryne Sandberg, Kerry Wood, and a few others.

The book ends with a coda from that poet of baseball Bart Giamatti, he who banned one of its greatest players (for not playing by the rules), who chided us to remember that it is just a game and that is why it is so transcendent, for two hours outside the river of time.

As the story draws to a close the team has changed hands several times and the unforgiving business of major sports prevails, though others have learned some of the lessons of Wrigleyville, as the neighbourhood calls itself, and some new stadia are more like Wrigley Field these days than Chavez Ravine (that is a memory test).

George Will

George Will

When I ordered the book I did so in the recollection that George Will is a wordsmith of excellence, and that assumption was amply vindicated by the light touch, the glib segues, the pertinent metaphors, and the economical allusions. Altogether a perfect game of a book. I read it in one sitting. Gulping it down.

Andrew Brown, ‘Fishing in Utopia: Sweden and the Future that Disappeared’ (2009)

This book came to mind when I read Michael Booth’s ‘The Almost Nearly Perfect People’ (2014) survey of Northern Europe. Booth mentions Brown’s book, too, in a rather left-handed way. Relying on my cataloguing system, I found this book on the shelf at the Ack-Comedy and had a look.

As when I read it first in 2009, I find it to be an understated book that neither condemns nor praises Sweden, the Swedish way, the Swedish model, and, accordingly, it does not satisfy the ideologues. It is low key in every way. It is more a personal memoir than an assessment of Sweden.

Brown lived in Sweden as a boy with diplomat parents, and later as a married man, and worked for a living in a sawmill. His experience of Sweden is far different from a travel writer who passes through for a few weeks of interviews in hotels and restaurants, and guided tours of the country side. His voice is muted and his comments are largely derived from direct, personal experience. Little is black or white, little is so clearcut to satisfy an ideologue. More importantly, his perspective is working class and from the hinterland, not urban middle class.

To judge from krimis Sweden is worse than Midsomer, every street, every town is replete with pedophiles, Neo-Nazis, Sven the Rippers, people smugglers, drug barons that put Latin Americans to shame, bankers who gave the Lehman Brothers lessons, and corporate villains to dwarf Enron, and worse. Anyone with a new car, a bank account in the black, a country cottage, a fine coat, got it by foul means. This compound of envy of the rich and imputation of evil to others is to be found in some other Nordic krimis, too, e.g., the Dane Jussi Adler-Olsen becomes poetic in his lyrical hatred of those he regards as rich. There is no depravity of which they are incapable. I fully expected to find his villains eating their own children, so I stopped reading his diatribes in malice.

But to return to Sweden, of course the pathfinders in this social criticism were Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. By the tenth volume in their Martin Beck series, the villains were cannibals. The first books in the series were police procedurals but along the way the authors ascended a soapbox and every page contained some sort of denunciation, not just of the evil rich, but the Swedish society that bore them. They attacked not just the filthy rich but the Social Democratic scrum who ran the place strictly for the benefit of the rich.

Talk about parochial! The authors lived in a decent society that had gone from subsistence farming to industrial surplus in the three generations, and they hated it for what it was not, namely, a communist Eden. It is rather like those self-righteous leftists in the 1960s who denounced Western liberalism as evil incarnate, while lining up to shake hands with Pol Pot. They do not know evil, that is for sure. Wake up! Look around. Try a few weeks in the third world. These very same types would spent hours defending Robert Mugabe, Muammar Gaddafi, or Fidel Castro, while condemning parliamentary democracy as a sham.

In contrast, Brown offers an everyday account of life and work. struggling to learn Swedish on the job in the mill. He finds much different from the England he left. As he notes many times, in Sweden there was a palpable sense of unity among the people he worked with which was aimed at getting things done. Ergo, the work in the factory was hard and everyone went at it with determination, including the owner. He contrasted this with his experience of working in a factory in England where the union made sure productivity was just enough to keep the wheels turning and no more. In Sweden everyone, including the union, wanted to get as much done as possible, whereas in England everyone, led by the union, want to do the least.

The unforgiving climate, the brutal history of the region with Germany on one side and Russia the other, and the recent past of grinding rural poverty combined, he speculated, to teach Swedes that the world does not owe them a living. They will have to earn it day by day. Brown met variations on this attitude in different guises, including church attendance. He found that religion, not necessary denoted by church attendance, seemed important to Swedes in the countryside where he lived. It was a sign of the larger whole beyond the individual.

That sense of a larger whole was comforting at times but stifling at others when he encountered a herd mentality such that no one dared to be different. Individual self-expression was actively disvalued in this milieu.

He is an outsider and is constantly aware of that and as constantly reminded of it by others. Swedes do not worry about what it means to be Swedish because they know it in their blood. They do not talk about it, they just live it. Brown wonders how this silent unity will wear with increasing immigration, made necessary by declining birthrates. The expectation to conform in Sweden is much greater than in England but there are almost no explicit clues about how to do it; he depended on his wife to cue his behaviour, say when checking out books at the library, cashing a cheque at a bank, buying groceries, all those everyday transactions that we do on automatic pilot he re-learned to do the Swedish way. For details read the book. He did learn to speak Swedish, by the way.

For the literal minded, yes there is quite a lot about fishing the book. It is Brown’s hobby and some of the most lyrical passages in the book are his weekends tramping through forests to lakes, amid man-eating mosquitos, to find a place to fish at sunrise, observing the breeze in the trees, the light on the water, the insects in the air. His father taught him to fish and he teaches his son.

The Sweden that Brown describes is all rather normal. Some people grizzle about taxes while cashing their pension cheques, denounce overpaid sportsmen while cheering them on. It is neither the paradise of its many rhapsodic admirers elsewhere, nor the putrid cesspit of depravity portrayed all too seriously by some krimi writers. It is no Midsomer!

Andrew Brown

Andrew Brown

He returned to Sweden as a journalist and covered some of the aftermath of the murder of Olof Palmé in February 1986. There is superb thriller that springs from that event, ‘The Death of Pilgrim’ (2013). Of course, the conspiracy at the heart of the plot is simpleminded, but the performances and tension are very well done without the gratuituous gore and violence of some Nordic thrillers on screen, like ‘The Bridge.’ However, I found the time shifts back and forth threw me more than once, the clothing and hair styles were not enough to indicate to me the context. Brown, to his credit, does not compare Palmé’s murder to that of Jack, but the aftermaths are certainly similar, the desire for meaning, and the desperate desire for there to have been a conspiracy to give the act meaning.

Barbara Pym, ‘Less Than Angels’ (1955).

This is a novel about the lives and loves of a group of anthropologists at a London institute. For those who have to have a label perhaps we can call it a comedy of manners like Antony Powell’s ‘Dance to the Music of Time,’ the token that defined the type.

Tom, Deirdre, Digby, Catherine, Miss Clovis, Mark, Professor Mainwaring, Alaric, Rhoda, Professor Fairfax, Mrs Foresight, and others make a living sharply observing primitive peoples in Africa, while unconsciously acting out the same rituals in London. That makes it sound more didactic and pedantic than it is, but the cumulative effect is to observe the observer.

Only the visiting scholar, Frenchman Jean-Pierre, makes a point of observing and cataloguing English ways just as he would in the heart of Africa. Though he is unfailingly polite and far more considerate of others than any of his hosts, they regard him as odd.

The professional rivalries and jealousies all ring true but are played out with a polite formality. In all the author has a light hand.

The rituals of the off-print, when it still existed, are amusingly set forth. So that is what one was supposed to do with them, I said to myself! My collection of them grew to occupy a filing cabinet and I put them in a yellow recycling bin when I left the Merewether Building. I wonder what the ritual is now with PDF versions? No idea.

The centre of this little drama is Tom Mallow who is devastatingly attractive to women, which he takes for granted in a vague way as he ricochets from one to another, barely noticing the differences from Elaine whom he absent-mindedly jilted a few years before, Catherine who was mother and wife to him without the benefit of law, and Deirdre whose cow-eyed veneration warms him. Digby and Mark circle around in the hope of leftovers.

He is also the golden boy at the Institute, though he never seems to finish anything. That omission does not diminish his glow.

Alaric who has never published anything, though he treasures dozens of tea chests full of field notes, devotes his considerable energies to writing caustic reviews of the books others dare to publish. He never has a good word to say. Still less when book review editors sometimes alter his prose to make it less venomous. That elicits another war of words between Alaric and the offending editor.

All of this seems true to life, if from an earlier time.

One of the themes is the way we have of idealising and wanting the life that others have. The urban, educated, worldly Londoners pine for the suburban calm, snug family life of the provinces. The provincials lust after the allure of London and resent the claustrophobia of the Sunday lunch en famille. It sounds leaden when I write it but in the book it is a feather on wind, conspicuous yet ephemeral yet entertaining to watch.

Spoiler alert!

Tom, chronically vague and oblivious of his surroundings, absent-mindedly gets himself killed and Deirdre discovers that she recovers from the shock of the news of the death of this demigod in a few hours. Digby is so amusing. Catherine convinces Alaric to burn his field notes and so free himself of the burden they have silently imposed on him all these years. Professors Mainwaring and Fairfax begin another tug of war over a new golden boy. Miss Clovis shelves Tom’s thesis and goes to tea. Gone and forgotten in a very few minutes.

I first read it sometime in the latter 1980s or early 1990s and the volume came to light again in the course of moving to the new abode. At that earlier time I had meant to read more by Pym, but failed to do so. I will try to do better this time around and I have plunked another of her titles in my Amazon basket.

Pym wrote a number of such novels but then fell out of favour. She kept writing them but her publisher decided she was old fashioned and stopped taking them. Her efforts to find another publisher failed for the same reason: fashion, or the perception of fashion, from the editorial desk. Then in the later 1970s some literary lions (re)discovered her, and her books came back into print…to stay. I expect the editors who rejected her work were paid handsome bonuses for such insight, but their names are now forgotten.

Barbara Pym at work.

Barbara Pym at work.

She, by the way, was crushed by the rejection. This all from Wikipedia.

‘Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat’ (2012) by Bee Wilson

When I saw the title on this Christmas present from Herself, I thought of Norbert Elias’s ‘The History of Manners’ (1939). The book at hand is broader than its title indicates. The subtitle pretty well sums it up, however, I would have been tempted to call it ‘Consider the Kitchen,’ because that is the culmination of the book.

Each chapter focuses on some essential aspect of food and eating in one word titles: fire, ice, knife, fork, grind, and, finally, kitchen. The fork which I begin to consider is important, to be sure, but it is only one element among seven others, hence my quibble about the title.

Ever wondered why a kitchen knife is sharp only one side? A table fork has four tines? Why was the freezer on top of the refrigerator until recently? Why are tin cans of food the size they are? Why are refrigerators powered by electricity when they use gas? How did the can-opener evolve?

Probably not, we take everyday things for granted, but there is much to learn from the answers to such questions. Successful innovations started by pandering to the expectations of consumers as in the case of refrigerators. The influence of major industries also figures, as electricity powered refrigerators, a boon to power companies because refrigerators, unlike light bulbs, are always on.

Here are few tidbits. Japanese knives are sharpened to 20 degrees while most European knives are sharpened to 30-35 degrees. Why? The difference traces back to a combination of the use of the knife and the material it is made from. The carbon steel layers that combine in a Japanese knife take the sharper angle. Though it is dangerously, lethally sharp it is confined to the kitchen for preparation. European knives are made from a different compound of metals, and the use of the knife is not so strictly regulated by convention to keep it in the kitchen, e.g., Europeans cut meats and carve birds at the table in way unknown to Japanese cuisine.

Most interesting of all is, of course, the greatest technology of cooking, the kitchen itself. At one time food was prepared in a lean-to behind the house, now the kitchen is often, usually the centre of home-life. There is the amusing story of post-kitchen renovation depression, after years of saving for, planing, selecting appliances, designing a new kitchen, when it is finally done…there is nothing to occupy every waking hour. There is but a void.

Chopsticks are another world. The lacquered and pointed Japanese ones are impossible. The flat steel Korean one with small raised striations for gripping the food are the easiest to use. In between are the plain Chinese wooden ones, which are used in such a quantity to threaten the forests of the country.

The discussion of the potato parer is wonderful. We put up with that primitive implement for generations until someone whom she names came up with a better way. We do put up with a lot of inconvenient things because that is just the way they are, until someone comes along and betters them.

In the 1920s Marion Mahony at Castlecrag designed kitchens in the front of houses, looking into the street, to reduce the social isolation of the housewife eliciting the consternation of local councils, mortgaging banks, and some clients. Certain patterns are ingrained. This incident is not included in this book but it seemed relevant.

By the way, the fork is credited to Catherine di Medici when wed to King Henri of France and mother to his successor. She had a household of Italians to Paris and from there emerged the fork. Of course Italians had been using it for years but it only entered the food culture when it was used in France. Another example of ideology over reality. By the way, she is routinely blamed for the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants.

Bee Wilson wears a great deal of learning lightly, and passes much in review with no distractions. An attentive reader will notice that there are a few aspects of the contemporary food culture that she disdains but without ever quite saying so, a subtlety that will pass most by.

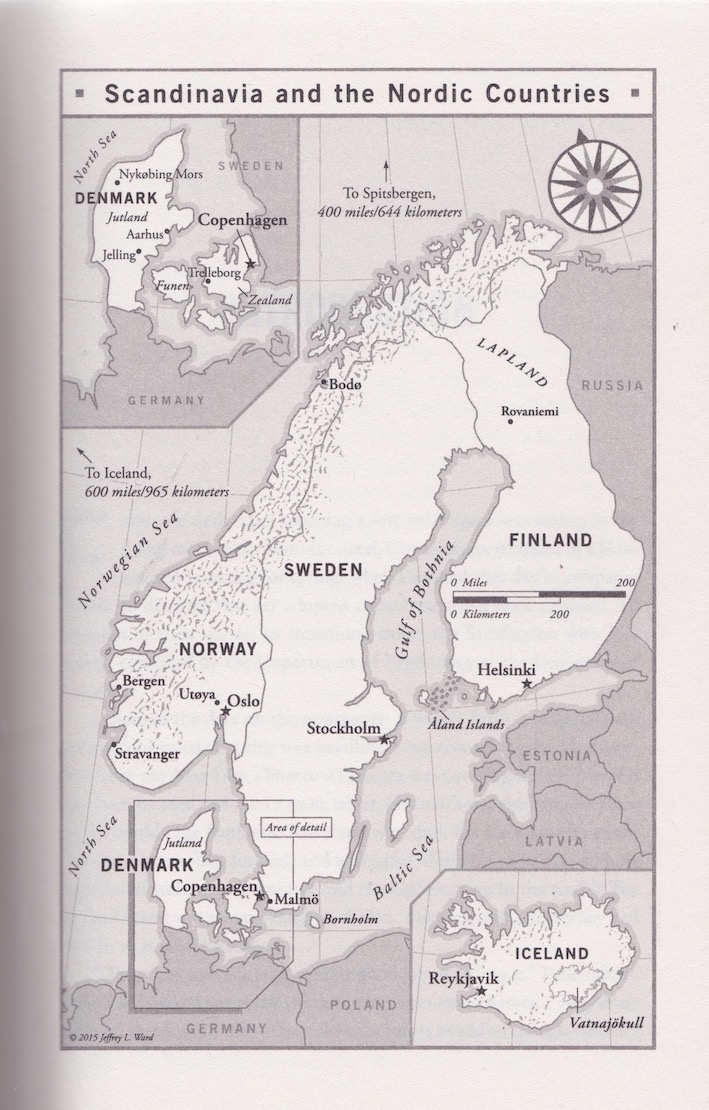

Michael Booth, ‘The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia’ (2015)

An amusing but informed, insightful, critical, positive, and biting though sympathetic tour through northern Europe. It starts with the definitions: no single term — neither Nordic nor Scandinavian — quite fits the combination of Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. ‘Northern Europe’ as a geographic term does not quite fit either, after all Iceland is way out there in the Atlantic all by itself.

‘Scandinavia’ does not include Finland, which has not participated in the Nordic Council and not in the Scandinavian Air Service, or NATO. As individual Finns are loners, so is their country. While the languages of the other four have much in common, not so Finnish. The Finnish language takes a lot of explaining, though grammatically it is, Booth says, simpler than most. It does not matter, since Finns do not use it much. He offers many examples of their taciturn nature. They are not the talkers that the Irish are. Their own term is ‘sisu’ which means just get on with doing it.

Iceland is the smallest, the most remote, the poorest, the most intimate, and all of that explains what they do and what happens in Iceland. There are a few snorts for reader when Booth samples some of the delicacies of Iceland’s cuisine. Iceland has long been very influenced by the United States and Great Britain, out that all by itself.

His analysis of Sweden as a mass society, my term, not his, has given me some food for thought. The explanation of the Swedish welfare state is that it makes individuals autonomous, i.e, they do not depend on each other [but on the state, yes]. Women are independent men; wives of husbands; children of parents, and so on. It is a benign decomposition of the civil society. What came to mind was William Kornhauser’s ‘The Theory of Mass Society’ (1959).

Norway? One word: oil. The wealth of the North Sea oil, despite the restraint exercised, has changed Norway and Norwegians, who now employ Swedish guest workers who peel bananas for them! Historic revenge against the colonial power! It is all explained in the book. See for yourself. The other distinction of Norwegians is their commitment to and engagement with the forests, fjords, and mountains of the country.

Denmark, where the author lives, is the odd one out. Perhaps because the author knows it best and he sees through many a veneer and what he sees, notwithstanding his efforts to balance the books, is not very pleasant. The courage to run that cartoon seems to have been born of a casual and still socially-acceptable racism, which often directed against migrants of any kind with the enthusiasm of a Tony Abbott. While successive Danish governments have been careful with the Kroner, Danes have not. The country has the largest private debt in the world, and its people work the fewest hours, and on every comparative measure of productivity rank low. It all seems rather fragile.

One of the strengths of the book is the use the author makes on the factual data available, e.g., to explode the myth, which I saw repeated just this hour on Facebook, that migrants are responsible for all, most, or any crime in Sweden.

He also makes good, though not systematic, use of the international comparative indices compiled by the Organisation for European Cooperation and Development, the United Nations, and non-government organisations.

The book seems to omit any account of the natives of the northern tip of the north, the Suomi peoples. They are mentioned but that is that. Who are they? How do they differ, how did they differ from Finns or Norwegians.

While Finland’s role as a buffer state, like Thailand between British and French colonies in Nineteenth Century south-east Asia, is treated, not much is said about Norway’s border with the Soviet Union and now Russia. Throughout the Cold War, Norway was the only western European state with a border on the Soviet Union.

There is no effort to define ‘utopia.’

Michael Booth

Michael Booth

The book is a salutory counterpoint to the personal reflections on Sweden in Andrew Brown’s ‘Fishing in Utopia’ (2009).

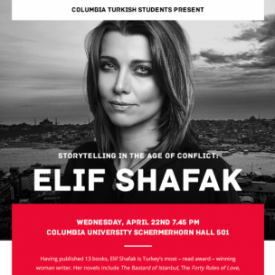

Elif Shafak, ‘The Flea Palace’ (2004).

Another item from my reading list for Turkey is this novel of 440 pages. It is well written and offers a cast of characters which represent some of the variety of life in Istanbul. There are many incidents, some great and others small, from the modus vivendi, so to speak, of the half-Moslem and half-Christian cemetery, the vanishing garbage, and the eponymous fleas. It is lively and, yet, well, I grew to resent having to spend my time reading it when I had such other alluring titles as ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (a treasured Christmas present from Herself) jockeying for my attention from the bedside table.

Despite the above remarks, there is no momentum in the novel. I was never quite sure why these characters were there and why I was supposed to invest interest in them. The assembly seemed to be arbitrary. Nor did I feel that, page-after-page, I was learning any more about any of them or the circumstances in which they lived. Instead the fevered imagination of the author produced yet another incident, twist, turn, upset, but well, since the prose was not going anywhere any twist or turn is just another twist or turn.

In so far as I got anything from it, it seems another exercise in ‘What does it mean to be Turkish’ that I found in ‘The Time Regulation Institute.’ Well do I remember all those talking heads on the CBC talking about ‘What it means to be Canadian.’ Same script here but different words. As Canadians have defined themselves by what they are not: American, British, or French, so some Turkish writers define Turkey by what it is not: European, Asian, Christian, Islamic. Not sure what the point is? Neither am I. Saying what it is not, does not leave what is.

I looked for other reviews to see if I had missed the point – it does happen. No professional reviews came to light and those I consulted, reluctantly, on Good Reads were, as usual, more about the reviewer than the book. Some liked it, but them some people like being hit with a stick. Others confessed that they had not finished it; my kind of readers, because I stopped, too. I am however grateful for one such reviewer who offered the summary below.

To make that summary meaningful I should say that the novel describes the live, loves, troubles, triumphs, lice, garbage, hair styles, reading habits, drapes of the assorted residents of an apartment building long past its prime, after an account of how it came to be built. The inhabitants who figure in the story are:

Flat 1, Musa, Meryem, and Muhammet: Musa and Meryem are married, but Musa is often absent. Their son is Muhammet who is a bullied at school, much to the distress of Meryem. Musa is no help.

Flat 2, Sidar and Gaba: Sidar lives with his dog, Gaba, and is obsessed with death.

Flat 3, Hairdressers Cemal and Celal: Separated as children, these identical twins are temperamentally dissimilar Cemal, who grew up in Australia, is a fussy extrovert, while Celal, who remained in Turkey, is painfully introverted. After reuniting, they run a hair salon on the ground floor whose staple is gossip about the occupants of the building.

Flat 4, The FireNaturedSons: This is a dysfunctional family dogged by ill fortune which tries to insulate itself from the others and, by extension, the outside world.

Flat 5, Hadj Hadj, his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren: Because the son and daughter-in-law work, most of the action in flat 5 involves grandfather Hadj telling his grandchildren stories which bore the oldest and confuse the youngest.

Flat 6, Metin Chetinceviz and HisWifeNadia: Metin isn’t around much, but HisWideNadia is: she’s a Russian émigré with an unhealthy obsession for bugs and a dubbed Latin American soap opera, ‘The Oleander of Passion.’

Flat 7, ‘Me:’ The narrator is a recently divorced university professor who think he is perspicacious. [The author is also an academic.]

Flat 8, The Blue Mistress: She is a kept woman for a merchant, which the neighbours accept despite the teachings of the Koran.

Flat 9, Hygiene Tyijen and Su: Hygiene is a compulsive clean-freak. Her daughter Su has lice, and that drives Hygiene to new heights of cleanliness.

Flat 10, Madam Auntie: The aged matriarch of Bonbon Palace, whose story only reveals itself towards the end, or so it is said. I cannot confirm this assertion since I ended my reading before the book ended.

The author has many other titles. Ahem. So be it. She also proclaims a PhD in political science. [Sounds of silence.]

More on ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ later!

Marc Bloch, ‘The Royal Touch: Monarchy and Miracles in France and England’ (1923).

This book offers a study of scrofula. Scrofula was a swelling of the glands that medical historians say was a symptom of tuberculous. It was sometimes known as the King’s Evil. What do kings have to do with glandular fever? What is a ‘royal touch?’ The reader might bear in mind the concept of charisma when reading below. A few Google images of suffers of such glandular disorders will push aside any smirks about mononucleosis. In late medieval and early Renaissance Europe tuberculous remained an insatiable serial killer.

There emerged the belief that the king’s touch could relieve the swelling. It was the King’s Evil in the sense that it an evil the king could relieve.

Why, how, and where did this conviction emerge? How did priests, abbots, monks, and popes react to the king’s intrusion into spiritual mysteries? How did word of this miracle spread? What use did king’s make of this power? Did others try to capitalise on this belief?

Bloch’s research is meticulous into original sources reaching back to the Eleventh Century to piece together something of the puzzle. Prior to the Eleventh Century there is no evidence that European kings had the healing touch. Charlemagne’s (748-814 AD) rule is well documented and much storied, but nowhere in this record is there evidence of him applying this touch. If Big Chas did not do it, it is hardly likely any lesser monarchs were at it.

With Charlemagne’s death and his Lear-like division and subdivision of his realm among his inheritors and successors, the record are fewer and less reliable as Europe fell into endless conflicts. Through these mists we can see, thanks to Bloch’s pathfinding, glimpses of the royal touch documented from the Eleventh Century and thereafter.

The healing touch of some monarchs was well enough known for the afflicted to travel great distances to seek it, and remember that travelling then usually meant walking. Nor was the king’s touch applied only to his own subjects, for these records report travellers from other realms seeking the touch of a foreign king.

The surviving reports confirm that healing effect of the king’s touch. The swelling went down. The petitioner cried out in gratitude, and so on. The doctors of spin have always been with us.

Very often for every king there were a number of pretenders and rivals with royal blood. Did they, too, have, or have the potential for, the healing touch? What is the origin of this miraculous power?

Despite its success, the evidence that remains does not suggest kings made an effort in the first instance to exploit this touch to win over adherents in any way. Rather the touch is applied only on special occasions like a patron saint’s day or the Resurrection.

By the way, the king also gave the petitioner a coin. This monetary reward might also explain why some sought the royal touch so that they could touch the royal purse as well as be touched by the royal personage.

One such ceremony.

One such ceremony.

To some churchmen the king was intruding into religion’s domain of he supernatural with these miracles. Caesar was playing god.

How does the healing touch of a king relate to the divine right of king’s to rule? While God chose the king to rule, he himself is mortal, and has no line to divinity. That line is reserved for the ordained priesthood who sacrifice the material world. Yet later when monarchs wanted to assert their divine status, they would invoke scrofula and apply the healing touch,.e.g., Charles I of England in the Seventeenth Century.

Part of the evidence Bloch considers with his usual care is the descriptions of Charlemagne in ‘The Song of Roland.’ The poem came into European literature long after the death of Big Chas, and Bloch’s point is that it reflects the attitudes of the time of its composition, not necessarily of Charlemagne’s times. In it Charlemagne is a priest-king, giving blessings and making benedictions, wearing holy vestments as his Christian armies battle the infidel Moor. Hmm, never noticed any of that when I read ‘The Song of Roland’ as an undergraduate. But then again I missed quit a lot as an undergraduate.

Inevitably by the Fourteenth Century rival claimants to a throne and rival kings of conflicting realms sought justification in the supernatural. The healing touch was one of the fronts of these contests. But as Bloch notes, it seems that most of this conflict was in rival publicity. The kings did not have heal-offs, but their supporters circulated stories of their healing powers. Did the stories consist of whole cloth, or were they based on something? Bloch cannot be sure. What he is sure of is that they were believed by those who sought the royal touch, and the stories were credible enough for those who circulated them to continue to do so.

Churchmen, be they Protestant or Catholic, discouraged monarchs from the ritual of the touch on ecclesiastical grounds. Some of the advice was given privately and noted in diaries. Others ever so carefully denounced the practice in sermons – delivered or written. In addition religious figures involved in the upbringing of heirs-apparent indoctrinated their charges to disavow the royal touch. The most successful instance of this last indoctrination is James I of England, himself an intellectual, denounced the practice and yet did it. By the way Elizabeth I also engaged in the royal touch, laying hands on more than a thousand subjects on one occasion.

The same story unfolded in France. French kings were reluctant to do it, and were skeptical about it themselves, while they were discouraged for doing it by Catholic advisors, yet they did it.

Why?

Because their subjects wanted it. When notice was given that the king, whether in England or France, would appear at a church or cathedral to heal the sick, they came in thousands. When a reluctant king, when a king who accepted the advice of the spiritual advisors refrained from healing ceremonies, the populace became restive and the word filtered back to the royal ear that his legitimacy was in doubt. To the populace it was proof of the king’s divine right to rule that he could channel the heavens in healing.

More than one king confided to his counsellors or his day-books, the pressure he felt from this expectation, decrying the sick who gathered wherever he went, who followed his entourage into the countryside, who appeared in even the most remote location.

Those intellectuals who devised and thought out the divine right of kings, including James I himself, did not include scrofula in the equation. In fact because of the proscription of religious authorities were determined to preserve their own domination of matters spiritual. The king is chosen to rule, but that does make him divine. This fine print was of no interest to sufferers who flocked to kings for succour.

At times there were concerns about contagion and the king would not be exposed to roomfuls of plague victims. However to withhold the divine gift of the healing touch from those most in need, did not encourage loyalty in subjects. How could a divinely ordained king fear disease? Though the transmission of disease was not well understood, it was common for those with the means to do so, to leave an area when the plague occurred there. French kings travelled around the country, not to solidify their rule, but to find places without the plague. When watching one of the episodes of a television documentary on the stately house of England, say, the viewer is sometimes told that this king or queen once stayed there. That was probably a case of tourism inspired by the plague back in London.

The practice continued long into the Renaissance and even the Enlightenment. In 1715 Louis XIV, who was hesitant to lay hands on the ill, saw 1,700 in one day. Equally impressive figures survive in court records of other monarchs. None can best Charles II (1660-1684) of England in his twenty-five year reign touched nearly 100,000 of his subjects in such rituals. All the while the religious authorities looking on must have been grinding their teeth.

Kings in Austria, Spain, Bavaria, Anjou, and elsewhere claimed the healing power in pamphlets but seldom practiced it. Rival claimants for thrones began to offer to heal, once the crown went on.

All of this became entwined with other claims of divine preference. The origins of the fleur-de-lys which had been in use for generations were re-written so that it all but came down with the burning bush.

Political upheaval, Calvinist monarchs, rival faith healers, science, and the Enlightenment, these all combined to end the royal touch, as later medicine tamed tuberculous. The Hanoverians never practiced it, either in Germany or in England. The Calvinist monarchs in the low countries denied it even more vehemently. The Hapsburgs in Spain, the Netherlands, Bohemia, and Austria followed the advice of their Catholic advisors and avoided this blasphemous practice. Not even Rudolf II, that most unconventional of monarchs who dabbled in the occult, figures in the history of the royal touch.

The king’s touch was at its most potent when his accession to the purple was consecrated in a religious service, at Westminster for Brits and at Rheims for French. For in the beliefs of the day when the priest blessed the new king for a moment God’s will was manifest in the flesh. Talk about charisma! On those widely publicised occasions veritable armies of diseased petitioners would show up, along with the rich and mighty of the land.

Such records as there are show that some sufferers came repeatedly for the royal touch, plain proof that it had not worked the first time, the second time, or the third time. Some observers took the view that many of the ill came for the coin not the touch. Others, still more cynical, said that the petitioners were petty criminals who used the occasions as a pretext for pickpocketing and worse. Contemporary scientists, including some on the occult side of the table, tried without success to find an explanation for the effectiveness of the touch. Some physicians who were empirically minded kept track of those who had received the royal touch, and found… they died. The data was held in secret.

Yet the demand for the practice continued until monarchs were discredited and destroyed by political revolutions. Though Bloch is slow to accept it, the final explanation seems to be some kind of collective wish fulfilment, though that wording is more Freudian than his, which takes it to be an expression of a collectively unconscious need to assert control over the inexplicable and unknown, or even unknowable.

The book is 220-pages of text accompanied by another 220-pages of notes, appendices, descriptions of iconography, and citations. He wears the research lightly but it is impressive.

Marc Bloch wrote many fine books, including the magisterial ‘Feudal Society’ (1939) in two volumes which I read in 1974. It was one of the great books I relinquished when I moved from the Merewether Building.

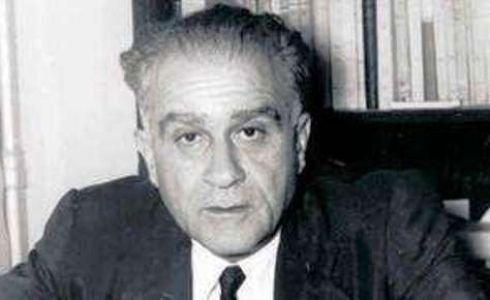

Marc Bloch, who murdered in Paris in 1944.

Marc Bloch, who murdered in Paris in 1944.

My main source of medieval history is, of course, Robin Hood on television in 144 episodes from 1955-1960. This Robin Hood was the dashing and charming Richard Greene. I now realise a very young Paul Eddington was Will Scarlett in this series.

Postscript

Is the royal meet-and-greet when the queen, king, or prince(ss) walks through a crowd some vestigial echo of scrofula. People line up for hours for a glimpse of the anointed one, and the fortunate few in the front ranks may even still today with maxed security get a royal touch. Do those so touched feel better, elated, special, or something? They must, or to be more specific, they must think beforehand that they will, and so invest the time, energy, and effort to get that position in the hope of being touched.

It all fits with Max Weber’s conception the charismatic as one carrying a special grace, and the appetite of others to share in it by proximity or adherence.

‘The Time Regulation Institute’ (1962) by Ahmet Tanpinar

Tanpinar (1901-1962) is one of the deans of Turkish literature, according to Orhan Pamuk, he of the Nobel Prize for literature. The master narrative of Tanpinar’s novels is its identity. Is Turkey Asian and Islamic or European and secular if not Christian. Is Turkey a traditional society rooted to and limited to the past or modern society making and re-making itself.

These themes are embodied in the satire in the creation and evolution of the Time Regulation Institute, a private corporation which, for a fee, will adjust clocks and watches to the right time in kiosks around the country. As life becomes more regulated, the demand for this service grows. No longer do sunrise, high noon, or sunset mark the days but rather hours and minutes.

The corporation is paternalistic, nepotistic, sexist, incompetent, and succeeds despite itself. It becomes home to a psychoanalyst who wishes to study its members, an alchemist who wants to use the clockwork mechanism for some purpose or other but he is secretive about it, wives, nephews, cousins, European trained scientists who cannot get any other work in a society where suspicion of foreign taint is routine, concubines, and wastrels. Its counter staff are all attractive young men and women in smart uniforms and they rake in the dosh.

After four hundred pages all this is laboured. The novel unfolds as a memoir by Hayri Irdal, the Institute’s first employee. There is much background of the various, idiosyncratic, zany members of his family, and the brooding presence during his formative years of a large long case clock that seems to work when it wanted to and at no other time.

The Institute is so successful that it attracts the interest of the government in search of tax revenue, and other shysters in search of easy opportunities. In the wings we have a double murder and suicide involving Irdal’s relations and friends. None of it taken too seriously.

In a difficult press conference in the early days of the Institute a parable was used to explain its purpose. Ahmet the Timely from centuries ago was quoted and his sagacity struck a nerve in the public. There was a demand to learn more of this sage. Despite qualms, Irdal writes a biography of this completely fabricated character, which is a great success and does much to cement the place of the Institute, despite the quibbles of some pin headed dopes in universities who point out that this man never existed.

The satire is the superficiality of it all, which in fact leads to its success. The fact that Ahmet did not exit frees Irdal from sticking to boring facts. The fact that no one needs to have the time regulated makes it a perfect commodity.

Perhaps to a Turkish reader what is most conspicuous is what is not said. Not a word about women’s head scarfs in the many references to the uniforms. Not a word about the calls to prayers five times a day as regulators of life.

Ahmet Tanpinar

Ahmet Tanpinar

As with Russian novels, I continue to find it hard to distinguish the characters by name, the more so with women whose names are strings of letters. How parochial am I.