I was looking for a biography of Mr. Mack (1862-1956) and this is as close as I could get and it is not a biography. Apart from a couple of early chapters about his playing career, it charts the seasons of the Philadelphia Athletics to 1945. It bursts with baseball clichés and brings back to mind some of the famous names, but there are no insights. Mack managed the Philadelphia Athletics from year zero 1901 to 1950, more than 7,000 games.

There is nothing about Mack’s ability to manage his teams, the more so as he aged and the players got richer. That was what I was looking for. I did learn why the name ‘Athletics’ and why the ‘White Elephant’ as a mascot. Members of the Philadelphia Athletic Club were the early investors at the turn of the Twentieth Century. It was a racket club. Skeptics said the franchise would be a white elephant, i.e., not succeed, and Mack and Shibe, the major shareholder, took that as the mascot image. They added the baseball either as a conscious reference to fickle fortune, as balancing on a ball symbolised in the Renaissance, or just because it was a baseball!

Mack played professional baseball from 1886 to 1896 and shifted into coaching and managing. He proved adept at managing some pretty wild and undisciplined characters, but how he learned to do this and how he did it, are not to be found in these pages. He also learned to treat management as a business, being himself part owner of the team.

In the unregulated era that covered most of his seasons, poaching players was common, rival teams would set up across the street to siphon off fans, journalists were unscrupulous, and many players found the money had to be spent on alcohol and women. Somehow this man who himself did not smoke, drink, or swear convinced most of his players to follow his example. Those he could not win over, he let go. By the way, that is the origin of the name Pirates for Pittsburgh, because it pirated players from other teams when it had steel money.

Shibe park was mostly .25 cent bleacher seats to allow its working class fans to attend, and the attendance gate was the only source of revenue then. Accordingly the Athletics could never compete with the New York and Chicago teams in money.

Shibe Park, interior.

Shibe Park, interior.

Shibe Park, Street view. Mack’s office was in the tower.

Shibe Park, Street view. Mack’s office was in the tower.

One of the distinctive feature of Mack was that he always wore a business suit when he managed. There he is on the dugout bench in a suit, tie, and hat with his players, scorecard in hand. Earlier in his career as a manager, before the A’s, he had dressed with the players and changed back into street clothes with them, as is still the norm in baseball. He stopped doing it because he found it hard to control himself, he told the author, sometimes after a stupid loss. He decided to stay out of the dressing room altogether, leaving the coaches to that realm, and establish some distance. Then when the wanted to talk to a player about that stupid loss, he would do so later that night in the hotel on the road, on the next day before the game, but in each case privately when cooler heads prevailed all around.

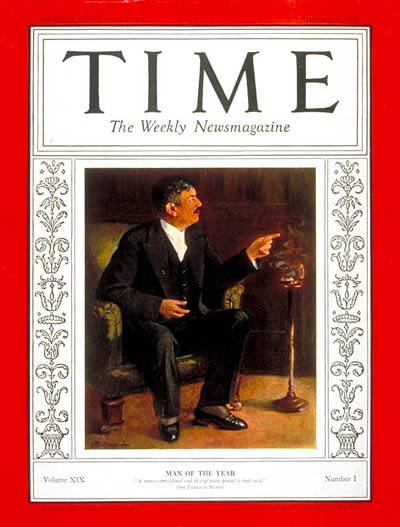

He became a national figure.

He became a national figure.

Of course the most impressive thing about Mack, and it comes through in this book, is abiding enthusiasm and interest in the game, its rules, its players, its symbolism, its continuity for more than fifty (50) years.

Category: Book Review

‘Red House on the Niobrara’ (2013) by Alan Wilkinson

The book is a day-by-day account of six months spent in the middle of nowhere on the banks of the Niobrara River in the Sandhill country of Nebraska. Nothing happens…but life. The roof leaks, winter hangs on too long, the grass needs mowing, the grasshoppers devour the kitchen garden, shopping trips to Chadron are iffy in the old wreck he drives…. Modest, matter of fact, impossibly romantic, hyper-realistic at times, and every word a labor of love.

This book is one man’s tribute to a woman he never met, she being Mari Sandoz (1896-1966). If you do not know Mari Sandoz, perhaps now is the time to make her acquaintance.

She was a writer and her titles include: ‘Old Jules,’ ‘Cheyenne Autumn,’ ‘They were the Sioux,’ ‘The Story Catcher,’ and ‘Sandhills Sundays.’ She was a lifelong proponent of the rights of the native American Indian, long before it was a fashion for celebrities to take up photo op causes. Wilkinson aims to write a book about her.

Wilkinson’s reasoning, Mr Spock, is that to write about Sandoz he would understand her better for knowing the environs that formed her, namely the Nebraska Sandhills.

Though the book takes the form of diary entries and is very chatty, it is at the same time more formal than many books I have read. (I suppressed a comparison here on the grounds that these reviews are always positive.) By ‘formal,’ in this case, I mean careful to give a full exposition so that the reader can understand.

Alan has visited parts of the United States many times but Nebraska is it, first Willa Cather and then Mari Sandoz. He has even been to Hastings and is proud of it! This is a man who knows quality.

Much as I enjoyed reading the book I was surprised he did not mention James G Niehardt who is surely the poet laureate of the Niobrara. Or did I blink and miss it? Nor does he say anything about the Indians that so dominated Sandoz’s imagination, but some are still around there. Though he went to Chadron several times he did not go on another hour to Alliance to see Carhenge! That is hard to believe. But then Carhenge is hard to believe, but I have seen it with my own four eyes.

Wilkinson says he does not like Sandoz’s novels but I have good memories of her ‘Cheyenne Autumn’ and ‘The Story Catcher.’ Memories which for the moment I will leave undisturbed.

Alan Wilkinson

Alan Wilkinson

Harry Mulisch, ‘The Discovery of Heaven’ (1992)

A masterpiece is every sense. At once finely wrought and sprawling. A large work inset with multifaceted gems. I liked it.

There is a ‘Jules et Jim’ ménage à trios, sort of, but much more erudite. Onno and Max are kindred spirits who without quite meaning to come to share a love of Ada. But the cosmos intervenes in a car accident.

Max is haunted by the ghost of his father, a savage collaborator with the Nazi occupation, and who, it seems, murdered his wife, Max’s mother. There are many echoes of the War and the transportation of Jews. Onno is prodigiously talented and gifted, so much so he can never do any real work, but all his days he ponders an indecipherable Creatan disk, as an amateur archeologist. Given the prominence of the disk for hundreds of pages, readers expect resolution of it, but I found none. As far as this reader could tell the disk drops out of the story 4/5ths of the way through. Onno has his own ghosts in his Calvinist family, though none as spectral as Max’s.

In all, the novel is a study of generational change, starting in the early 1960s and ending in the later 1980s just before the Wall came down. If you have to ask what Wall, you weren’t there.

Between the parts of this 700+ page magnum opus, two angels discuss the events and people. The book is both earthy and divine.

Max is a radio astronomer who studies the sky by staring at data on his desk. Onno is a know-it-all who finds he knows nothing at all.

Both Onno and Max grow up and mature and grow old, and change. Only the comatose Ada remains the same. The stars kill Max.

The book reflects the preoccupations I found In his novel ‘The Assault’ which still ranks very high in my all-time list: the War, the Hunger Winter, the loyal Moulaccans who foolishly believed that loyalty would be rewarded, musical chairs of Dutch governments, the chasm between Calvinists and Catholics, and the divide between Amsterdam and the rest of the country.

Foreign and then Dutch Jews were deported through the Westerbork transit camp.

We something about this at the Museum of Dutch Resistance in Amsterdam in 2014.

We something about this at the Museum of Dutch Resistance in Amsterdam in 2014.

This tale is, well more than one tale and it is too much to recount and, though I read It in great gulps, it lacks the focus and urgency of ‘The Assault’ with its very satisfying resolution when the message is at last delivered. This novel is too prolix for that. But it is one fine ride like few others, with Hegel, Wagner, Leibniz, Kant, Rousseau, and of course Machiavelli all mentioned along the way. He tries to out do Umberto Eco and Dan Brown toward the end, and then it tails off…..

Harry Mulisch

Harry Mulisch

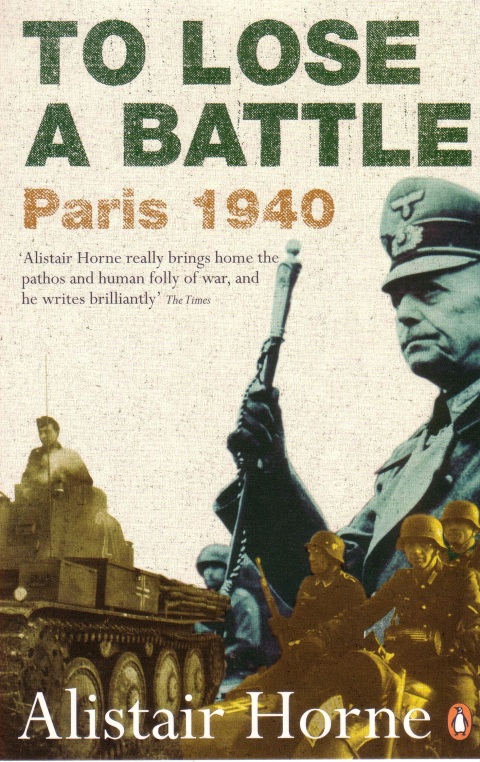

Alistair Horne, ‘To Lose a Battle: France 1940’ (1969).

Where were you when France fell? That was certainly a memorable day for those born in the 1920s.

Impregnable France, eternal France, the France of Napoleon, the France of Clémanceau, the France of the taxi cab offensive, the France of Verdun, the France of Jean d’Arc, indomitable France, this France dissolved in the powerful acid of the Wehrmacht.

‘Thank God for the French Army,’ said Winston Churchill in 1935, for it was the bulwark that stayed the German beast. Yet less than five years later it proved to be a wall in a Japanese house, made of paper.

In 1940 where was the France of Union Sacrée of 1914-1918 when all social strata, all social classes, all degrees of political opinion, all regions put aside their historic animosities and united without question against Les Boches? It was gone.

In the Twenties French politics descended into blood sport. With the ancient external enemy vanquished and emasculated, French political differences sharpened once again, each with a backlog of grievances to be settled. Without an external threat to encourage a degree of forbearance, cooperation, and restraint the gloves were off.

Any of this starting to sound familiar?

One’s opponents were no longer well meaning, but misguided, people. They were detestable enemies whose very name was sin. They were alien spawn to be eradicated right now, if not sooner. With such people compromise is impossible!

Internal enemies completely replaced external enemies and they were everywhere: in schools teaching pernicious doctrines from science to scholasticism, in trade unions practising black masses, in plutocrats dining upon working class babies….. No vituperation was enough! No exaggeration too far. No lie too big. From 1934 many observers thought civil war in France was imminent. When such a war began in Spain, they supposed the example would light the many powder kegs in France. Against that backdrop, the drama played itself out.

Yes, Mortimer, it is all starting to sound like the Tea Party and Fox News.

In the 1936 election some of the very many political parties actively campaigned under the slogan ‘Better Hitler than Blum.’ Léon Blum was the leader of Socialist party and he was feared more than Hitler. Ludicrous, to be sure, for Blum was a moderate to his finger tips and a true patriot and if any thing he was a brake on the hotheads in his own party. Blum, by the way, was a Jew, and the explicit attacks on him in parliament for his Judaism authorised a hate campaign in the press the like of which not seen before or since. His every gesture and word was sign of his nefarious plots. Compared to Blum, Dreyfus was small potatoes.

To the most right-wing parties, blocs, movements, and groups the real threat was Britain, seen to be constantly scheming to grab the French Empire. Albion was the enemy, not Hitler. And Albion’s agent was that Jew Blum and his ilk.

Blum did form a Popular Front government in 1936, striving to keep France out of another war. Though by then the die was all but cast. He depended on the votes of the Communists and the Radicals (centrists, despite the name). Neither was reliable, each had its own agenda.

In the last decade of the Third Republic political musical chairs is the only fitting description. The electorate was fractured into innumerable political parties which combined into coalition governments, briefly, to divide the spoils of office, and then lose a vote of confidence. An incoming minister grabbed everything thing that was not nailed down, cancelled all commitments of the previous minister, signed a raft of new commitments, and six months later was thrown out of office when that coalition failed. Democracy at work.

During one five year period there were eleven (11) ministers of defence. Each dedicated upon entering office to demolishing everything the predecessor had done.

Contracts to build tanks, were torn up. Though the government paid a penalty to the contractor, the tanks were not built. To secure as much popular support as possible, contracts for tanks, aircraft, artillery were spread widely. Instead of concentration on one fighter plane, France built a dozen different types around the country, with no economy of scale. But it bought votes.

One minister boasted that in France it took 18,000 man hours of work to build a warplane and a mere 5,000 man hours in Germany, proving the superiority of the French approach that generated more demand for labour! That Germany thus produced three planes to every one in France was beside the point.

In 1936 when German workers put in 60 hours week in defence industries, those in France were awarded a 40 hour week with much jubilation. That ratio of 3:1 does not capture it all. German industries were more efficient because they were centralised. Germany did not dabble with a dozen different kinds of warplanes but concentrated on only a few to reach economies of scale far beyond anything the French could do. Finally, the brutal facts of demography apply. Germany had nearly twice the population of France, the more so when it digested Austria, the Sudetenland, and Czechoslovakia.

It gets worse. The French Communist Party had worked hard to organise workers in defence industries on orders from Moscow. From the mid-1930s obedient to Stalin’s orders some of these workers sabotaged French war industries. Some of this sabotage occurred during the war in 1939! The Soviet policy was to make it easy for the Germans to go West.

In all of this the French army was complicit, though of course after the Defeat, the generals spent the rest of their lives lying about it. Ambitious generals had learned to play the parade of governments off against each other to win promotion and ever more gold leaf on the kepí. One general after another advanced his career by telling the ministers of the day what they wanted to hear. Dissent within the ranks was silenced, e.g., Charles de Gaulle was struck from the promotions list, posted abroad, and forbidden to publish his criticisms of military strategy along with several others.

Here is one singular example. Pétain blamed the Defeat on the politicians who had cut the defence budget. Hmmm. Class! Who was minister of defence when the defence budget suffered its greatest cut? Go on, guess! Phillipe Pétain! The generals blamed politicians, Free Masons, protestants, free thinkers, women wearing slacks, school teachers, physical education instructors, Jews, Albion, the Belgians, the Dutch, newspapers, journalists, novelists, travel writers….. Any one but themselves. Now back to the Third Republic.

When vitriol replaced argument in public life, the night creatures dared to reveal themselves: anti-Semitism became a public pastime. The Dreyfus Clock was turned back. The Communist Party of France openly acknowledged its obedience to Moscow. The plutocrats stole pension funds on a national scale. Political interference meant even those few police officers who were not corrupt could not investigate major crimes against persons or property. It does all seem like the End of Days.

All of this is a familiar story, what Horne adds to the picture was Gallic arrogance. As France was the fountainhead of European (read ‘World’) civilisation, others would rush to its side if ever the worst happened. This, Horne suggests, was one of the central, unspoken, shared assumption of every French government after 1919. It followed that no matter what the French did or did not do, the firemen would come. Though the firemen are lesser beings, they are useful, and they will come from England, America, Canada, Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia…. to save us even if we set ourselves alight.

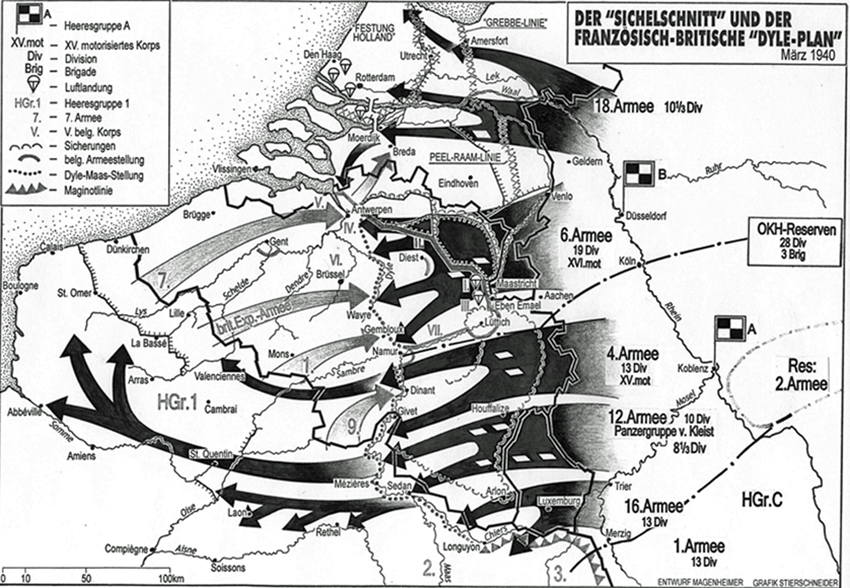

It seemed to this reader — though Horne does not say it — that part of the French response to the German offensive in May 1940 was that its generals, from Maurice Gamelin to Maxime Weygand, thought, moved, and acted on trench time. They were in no rush because after all trench warfare goes nowhere. If Gamelin took three days to think things over, there was no rush. Yet the German armoured Panzer divisions were moving 40 – 60 miles a day! By the time Gamelin made up his mind to authorise the French 2nd army to disengage and pivot, the Germans were no longer within striking distance. Indeed the 2nd army had already been forced to retire because the Germans had outflanked it. Gamelin used neither radio nor telephone but motorcycle couriers to communicate with his five armies.

Gamelin reacted to this pressure of time by delegating everything downward. He would make no decisions. Let others decided, and then be responsible for the consequences. But of course no one else could give orders to all the armies and generals involved but Gamelin. Very quickly each French army was left in isolation to cope as best it could alone. There was no coordination. Here’s an example. The British Expeditionary Force of General Gort was under the command of a French Army in Belgium. As the Germans were crossing the Meuse River, Gort had no orders, information, or contact from his French commander. None for eight (8) days. Is it any wonder he decided to stay close to sea.

Horne makes it clear that Hitler prevented the Germans from refighting the last war. He was the only head of state who had been in the trenches in World War I, though Churchill and de Gaulle had been, they were not heads of state until later. Moreover, Hitler was an autocrat who had powers no democratic politicians in England or France ever had. Got the picture?

Hitler loved machines and he reviled the trench warfare he had experienced. When he rebuilt the Wehrmacht he wanted tanks and airplanes. When an obscure German Colonel Guderian advocated tanks, Hitler promoted him to give his advocacy a wider audience.

Heinz Guderian

Heinz Guderian

When French Colonel de Gaulle advocated tanks, he was struck from the promotions list and exiled to Syria. Germany built tanks, armoured cars, self-propelled cannons and concentrated them in regiments, divisions, corps, and armies. Mobility and manoeuvre were the watchwords.

The French were stuck in 1916. Their major strategy was continuous defence of the whole border from Switzerland to the North Sea. Not one foot would be yielded for one instant to the invader. The manpower needed to defend these hundreds of miles was gigantic. In addition, the commitment to static defence led the French General Staff, which reluctantly accepted those new fangled weapons of tanks and airplanes, to distribute them all along the line. Every division had a few. They were never concentrated, and once the shooting started, it was not possible to concentrate them, to deliver a resounding blow. Instead the tanks and airplanes went into battle in small groups. A German Panzer division of 200 tanks would encounter 200 French tanks in a week, but each time in groups of 5. No contest, even though individually the French tanks were technically superior. When 200 Panzers hit 5 Renault tanks, it was over in a muzzle flash or two.

In fact, the French manpower required for continuous defence was so great that there scarcely more than two divisions in reserve. This fact dumbfounded Churchill when he was told that. Note: very often the troops held in reserve outnumber those in the line, so that when the enemy attacks or retreats a large, fresh force can be unleashed.

The manpower shortage was produced by the strategy, but it was compounded by the politics of the Third Republic. To buy votes successive ministers had reduced military service and inserted exemptions of all manner. The exemptions were so numerous that when Paul Reynaud, a minister who feared the Germans and was serious about defence, cut 30 pages of exemptions from the conscription law, another 20 pages remained. Wine was deemed of national importance and anyone who worked in the wine business was exempt, etc. Renaud angered many people and was dumped from the job.

To his credit Reynaud kept trying and was prime minister during the fateful six weeks that led to the capitulation. His coalition cabinet was full of rivals and pretenders and he had little authority among them. Yet he persevered and in the final hour, he very nearly alone wanted to fight on. It is clear from Horne’s pages that the generals — Gamelin, Weygand, Pétain — gave up long before he did.

They yielded in part because they, and many others of the haute bourgeoisie feared a repeat of the Paris Commune in 1940. All French military police (Garde Mobile) had been concentrated in Paris to keep order, code for preventing a left wing revolution or right wing coup d’état.

At the eleventh hour they did prefer Hitler to Blum.

Horne lays to rest one of the myths of the War concerning Hitler’s order that halted the Germans short of Dunkirk. The German armour was miles in advance of infantry and artillery, many miles. Moreover that steel tip was by then at half strength, with battle loses, mechanical breakdowns, and the exhaustion of the men. Fuel trucks were finding it hard to get through the debris. A halt had been considered several times before. In addition, the German intelligence estimated only 40-50,000 Allied soldiers in the Dunkirk enclave, and the conclusion was that the Luftwaffe would suffice to disrupt any evacuation on that scale. It was also supposed that RAF’s losses had been so great it could not cover any evacuation. Finally, because Gort, having withdrawn to Dunkirk, in good time had fortified his position against tanks. Ergo, Hitler decided to draw a breath. The halt was not a conciliatory gesture to the British nor was it a blunder. It made sense in the context.

Horne also emphasises that the Germans, surprised at the speed of their successes, had no plan for a next phase, namely an invasion of Britain. Nothing. Nada. Zip. So why be in a hurry?

The German were successful in part because the French assumed the strategic target was again Paris as it had been in 1870 and 1914, and never realised that the strategic objective was the North Sea, having first lured massive allied armies into Belgium and the Pas de Calais, and then cut them off, encircle them, destroy them, and only then move on to Paris.

The vacillation of Belgium before the war played in the hands of the Germans. Belgium shifted back and forth between a French and British alliance and then neutrality. The Belgians did not want the Maginot Line extended to their frontier with France and lobbied hard against it. Yet, fearing arousing the Germans, they did not want an explicit alliance with France or Britain. Uncertainty all around.

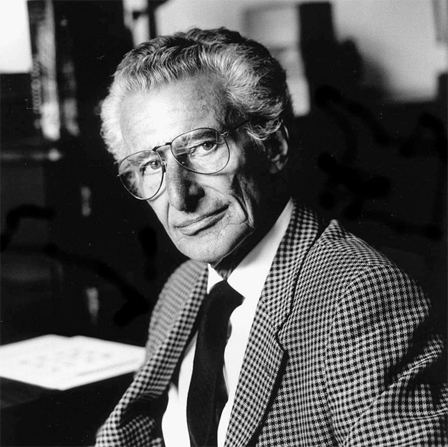

Alistair Horne

Alistair Horne

As to the book itself, Horne’s command of the subject is complete. Highly recommended. However there are typographical errors in this the third edition which were there in the the first when I read years ago. Horne’s style is orotund. It takes him a long time to get to the point and the passive voice confused me more than once. More than half the book is devoted to the details of armies, movements, skirmishes, battles of little interest to me but in between there are shafts of insight into the people and events that repay the reader.

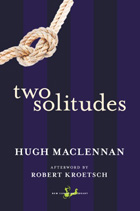

Hugh MacLennan, The Two Solitudes (1945)

This is the Great Canadian Novel. It appears on every list. Critics make a name for themselves attacking it. Surely that is a sign of its place at the top of the tree.

It is ambitious, peopled with every type, and set against the backdrop of the two World Wars. The two solitudes are the Two Canadas. When MacLennan planned and wrote the book these were two ships that passed each other in the night, night after night.

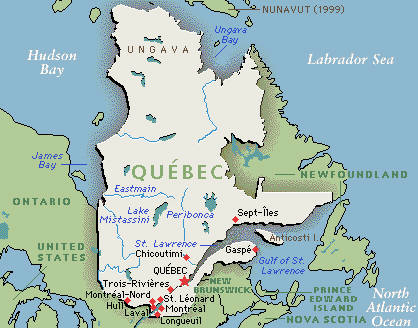

Quebec is one and the other is English-speaking Canada.

The novel opens in rural Quebec in 1913, and rural Quebec then was Quebecois. The fertile plains along le fleuve Saint-Laurent, being the only land suitable for farming in Quebec, were settled by the Normans who came to Canada, there to be abandoned by the Parisiennes and left the mercy of perfidious Albion. Thus did Quebecois hate both the French and the English, and hold themselves to be unique.

Along the way the dominance of the Catholic Church in Quebec is manifested in ways that seem hard to believe today. Yet in 1960 most schools in Quebec were Catholic, offering little science, no English, and only to glad to see girls leave at 16. Though the role of the Church is emphasised MacLennan fires no cheap shots. It is a tragedy: a clash of sincere and opposing worlds.

Likewise the resistance of Quebec and the Quebecois to change is there. But not to change is to die, argues one character. So be it, intones another; then we die as God made us.

The island of Montréal is the exception to Quebec in every way and yet also the exemplar of it. It is the redoubt of the Quebekers who owned most of the province. These are English-speaking Presbyterians tracing back to Scotland; they who built McGill University for their children. For generations the Boulevard Saint Laurent in Montréal divided Quebekers from Quebecois. No one spoke of the border and every knew.

West of St. Laurent

West of St. Laurent

Tourist, even today, spend their time on the English side of that line and never know. it.

The principle characters come from two families, the Tallards and the Yardleys. The action encompasses the anti-conscription riots of 1917 in Montréal, the Great Depression, and the advent of World War II. There are several threads to their interactions but the chief one concerns a Tallard who is that rarity – both an English-Canadians and a French-Canadian. That is his father was Athanase Tallard and is mother was Kathleen Morgan (an Irish Catholic woman who never learned to speak French). Anthanase and Kathleen married and raised a son, Paul. One then could say the book is a bildungsroman.

There are marvellous passages describing the landscape, that mighty river, the weather in sultry Montréal and the bitter snow of the winter along the river, the smell of crops, the sound of frosted grass cracking underfoot….

Each of the many characters is given the camera and treated with respect of a Frank Capra character actor. There are no one-dimensional plot devices among them, each is a well-rounded human being. But, but, but sometimes it does seem didactic. Every perspective has to be enumerated and considered, however little it might add to the truth of the story.

I read this in graduate school in the 1970s and formed a high opinion of it but had forgotten most of it. Time then to re-visit it.

MacLennan has always maintained that none of it is autobiographical, by the way. He himself was from Nova Scotia and his other novels are set there, like ‘Barometer Rising’ about the destruction of much of Halifax in World War I when in 1917 a munitions ship bound for England exploded in the harbour.

Quebec did change, first in Montréal when post war European immigration brought new people to Canada’s most European city who spoke neither French nor English and whose ambitious were not focussed on the tension between French and English. They came to North America for a better life for their children, and that better life spoke English. Their appetite for English is one of the proximate causes for Quebec French-language nationalism; it was a reaction to this third factor, an effort to capture them by the language. Earlier there had been Jean Lesage and La Révolution Tranquille in the early 1960s to bring Quebec into the Twentieth Century. Lesage and his most creative lieutenant René Lévesque put science in the school curriculum, took religion out of schools, encouraged retention in schools, placed a premium on technical subjects like engineering and accounting, lured ex-patriate Quebecois home, invested in the film industry to portray Quebec Nouvelle, borrowed to built Hydro-Quebec which still sells electricity to Toronto and New York City, and most of all spoke French….all in the name of Chez Nous.

Hugh MacLennan, school teacher by day.

Hugh MacLennan, school teacher by day.

THE novelist of Montréal is Gabrielle Roy whose books are studies of ordinary life with the weight and integrity of a Paul Cézanne still life. ‘Alexandre Chenevert’ (1954) is one of many of her many titles that has stayed with me. It has been translated and titled ‘The Cashier.’ A little gem in my view, small and perfectly formed. Her best know book is ‘The Tin Flute.’ There are many others, like ‘Where Nests the Waterhen.’

File this fact under extraordinary but true: she appears on the Amazon Canada web site, and has for some time now, as Roy Gabrielle! Figure that one out.

I said Quebec and Quebecois above to omit the million or more French-Canadians who live outside Quebec in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta. The sentiments that MacLennan charts may be found among them, too, but they have never participated in or warmed to Quebec nationalism. Every time the Parti Quebecois hits the headlines the French-Canadians in the Atlantic and Prairie provinces cringe. They want no part of the English-Canada blowback on Quebec.

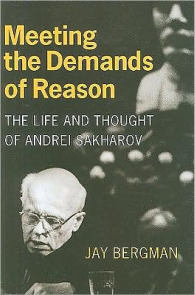

‘Meeting the Demands of Reason: The Life and Thought of Andrei Sakharov’ (2009) by Jay Bergman

Andrei Sakharov designed and built hydrogen bombs for the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. He also dissented from the regime during much of that time until he became a full-time dissident in the latter 1960s. I have wondered how he compared to Robert Oppenheimer and this is a start in finding out. Strangely enough Sakharov loomed larger on my horizon than Oppenheimer because Sakharov was a celebrity dissident in the 1960s, repeatedly in ‘Time’ magazine and in the highbrow publications of the Centre for Democratic Institution from which I drank at the time, whereas Oppenheimer was a man of the past.

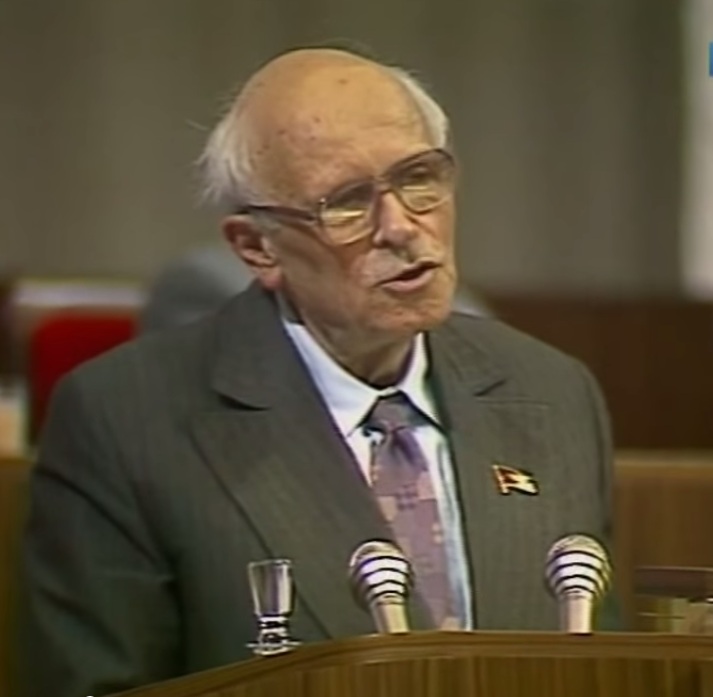

Andrei Sakharov, 1989

Andrei Sakharov, 1989

Sakharov was man and boy Soviet, knowing no other way of life like the millions of others. His family was secure and comfortable by the standards of the time and place, though Stalin’s purges and the myriad of local purges that cascaded onward in time caught up with members of his family, first among the older generation of uncles, and then aunts whose crime was to have married that uncle, and then Sakharov’s generation, an arrest here, a deportation there. Even so his loyalty to the regime was unalloyed.

He grew up in a musical family, while his father was a successful physics teacher who wrote and published numerous approved high school texts on the subject. Sakharov’s interest in and aptitude for mathematics blossomed and he went to the head of the class and stayed there. Having just seen ‘The Imitation Game’ (reviewed elsewhere on this blog) I compared him to Alan Turing.

He failed the physical examination for the Soviet army in World War II; consider for a moment how low that standard must have been. He had an irregular heart beat most of his life. Instead he signed up to work in an ordinance factory. There his capacity to reduce confused and confusing reality to rows of numbers led him to several innovations which made his name as a coming man.

One example suffices. To test artillery shells for defects the method was manual, in every new batch several shells were dusted and examined with a magnifying glass for cracks in the casing. Until that test was passed the batch waited. If one crack was found the whole batch was rejected. Neither effective nor efficient. Sakharov devised a laser to pass over each shell individually and ping on cracks so that individual shells could be rejected but not whole batches and the production line kept moving the whole time. I have take quite a few liberties in this description to make it accessible; as they say in movie credits, ‘based on a true story.’ In the same spirit that could be motto for Fox News rather than that ironic statement ‘Fair and Factual.’ It is ironic isn’t it?

There is one of similarity to Turing. Both turned to automation for tasks that previously had been done by hand, just as the machine gun replaced the bolt action rifle.

Sakharov’s change from cog in the mighty wheel to dissident came slowly. He saw neighbours and colleagues foully treated and it could not all be explained by the war. Jews were made victim. A loose word about comrade number one, and … Exactly, no one quite knew.

Moreover, when he left the laboratory for the factory and later the weapons plants, which were really cities in themselves, he saw how badly treated workers and their families were, despite the endless rhetoric of the workers paradise. Also he choked on the ritualistic evocation of Marxism-Leninism at every official juncture. Just as many of us have choked on the empty and ritualistic evocation of God on public occasions like the Gallipoli ceremony.

He was a brilliant scientist, a claim reiterated many times in these pages without a satisfactory explanation of this brilliance or how it was recognised as brilliance by all the dimwits around him. Well, they have to be dimwits if they did not reject the regime per Bergman.

Gradually, Sakharov tried to use the status he had to help individuals and in time he realised that the Stalinist regime was the problem, and that it rolled on even after its creator died. He retained a faith in the Soviet promise but thought it perverted by Stalin. At first his supposition was that the Tsar did not know, in the old Russian proverb, only slowly concluding that the Tsar was the problem, then Tsarism including the people who wanted a Tsar, call them the Tsarists.

Though his interventions were few, carefully judged to appeal to Soviet values, and argued on pragmatic grounds they yielded a vigorous reaction. He was named as errant in public by Chairman Khrushchev himself.

In time he realised there were systematic and systemic failings and those he saw first and most clearly and which he quantified were the deaths and defects causes by the radiation of atmospheric testing of hydrogen weapons. He compiled spreadsheets of data that showed approximately 10,000 deaths caused over three generations by the radiation released in a single atmospheric test. He thus argued for underground testings, which had technical limitations, in his immediate environment, then at closed and secret scientific conferences, and then by writing to the Party Chairman.

Yikes, this drumbeat was readily characterised as unpatriotic, just as Edward Teller tried to portray all other others who lacked his one-eyed enthusiasm for ever bigger bombs as UnAmerican.

His ground shifted from urging reforms on pragmatic grounds to improve Soviet society to urging reforms because they were morally right. This put him beyond the pale; it put him in Groky four hundred miles east of Moscow.

There is a personal element as well. Sakharov saw and despaired at medical treatment his first wife Klava received. Doctors at elite clinics could not interpret X-Rays to his mind. She died in a great pain as he watched. Perhaps it could happen anywhere but it happened to him and it was another fissure in his allegiance to the Soviet Union.

One of the things that tied Sakharov to the Soviet regime withal his objections was the need for weapons not because of the Cold War with the West but because of Mao’s China and its erratic course as perceived from Moscow. That was a new perspective to me.

One of the things that loosened the tie to the Soviet regime was the Prague Spring of 1968. We read that many Soviet dissidents saw in those Czechoslovakian changes a hopeful future for the Soviet Union itself. When that door slammed shut in August 1968, those Soviet dissidents who championed reform from within communism lost hope. It was proof that communism could not change. This was another new perspective to me and a striking one due to our recent visit to Prague and our tours of its communist relics.

The many and varied dissidents could not agree among themselves and spent at least as much time and effort in undermining each other as working for reform of the Soviet way. (Sounds familiar to any seasoned committeeman.) They tried to organise themselves in the way they knew, a central committee with a rigid hierarchy….and that did not work. All of this backbiting made it easy for the regime to isolate and pick off dissidents.

He became a supporter of any and all dissident causes from ethnic revanchism to free masonry, seemingly without discrimination. His enemy’s enemy became his friend. Anyone who dissented from the Soviet way was his friend, or so it must have seemed to the Communist authorities. He also demonstrated a political naiveté born of his sheltered existence in believing that some how all these dissenters could combine within the abstraction of human rights, when some of them did not want human rights, they wanted their land and would gladly kill to get it! See post-Soviet history for the data.

He seems to have had a charmed life in that even when stripped of his scientific duties, he was still paid, retained his apartment, had a limousine and driver at his service, was available to all manner of foreign journalists in Moscow to whom he spoke ever more freely, including offering advice to the Reagan administration on how to negotiate with the Soviet leadership – rather like Jane Fonda encouraging the North Vietnamese to kill more American draftees to shorten the war. (Oh, yes she did.) For a man who was oppressed and repressed he published a very great deal in the way of political opinion, a bibliography of which runs from page 413 to page 431.

Mikhail Gorbachev appeared but for Sakharov he was too little, too late. Sakharov wanted everything now, and Gorbachev was carrying a heavy load on thin ice. That Gorbachev let him return to Moscow and appointed him to ceremonial offices was accepted but it did not temper Sakharov who but now seems unable to trust anyone or give anyone else credit for good intentions. Then Sakharov died and Gorbachev offered his widowed second wife, Yelena Bonner, a state funeral which she accepted. That became a Saint Bartholomew’s circus for dissidents, for apparatchiks who wanted a halo, for Western journalists looking for easy copy.

I should have said earlier that Bonner, of Jewish descendent, did much to focus Sakharov’s political interests. She had a much more general and coherent view of the Soviet Union in contrast to Sakharov’s piecemeal perspective. She became a comrade in arms, as she appeared to be at the time in their hunger strikes.

Yelena Bonner

Yelena Bonner

Returning to the comparison with Oppenheimer, this book being my only source, it is not clear to me if Sakharov had management responsibility akin to Oppenheimer’s. None are explicitly mentioned though Sakharov is occasionally referred to as ‘Director’ of this project or that and the word implies management to some degree.

The book was a hard slog. The implied thesis behind the title seems to come straight from Karl Popper that science and democracy unite in falsifiability. Neither assures perfection but each can falsify mistakes through rational argument and evidence. Ergo, the more rational and scientific Sakharov was, the more he had to reject (falsify) the Soviet system and make his way (intellectually) to democracy. Oh dear, does that mean the Soviet scientists who did not move this way must not have been rational and scientific after all, and likewise that the Western scientists who pined for authoritarian government, hello Ed Teller, were not either. Such consistencies do not worry the author.

Our author has it that one of Sakharov’s deepest concerns with the Soviet Union was the easy and irrational way in which scientific arguments and evidence put before the top leadership were cast aside. Stalin and Khrushchev having grown up among farmers rejected scientific biology on the strength of that background. Bergman implies this rejection of scientific, reason, is one of the core evils of the Soviet Union. Arrrrrrrgh! What would Bergman make of political leaders today in the West who reject climate science in one sentence or less? Evil?

Similarly, Bergman in contrasting Sakharov with that other even more famous dissident of the time Alexander Solzhenitsyn takes Sakharov’s side because Solzhenitsyn was too much a believer in the mystical soul of Russia for the scientific age of reason and democracy. Hmmmm. What would Bergman make of those Tea Party nut cases invoking God above to reject vaccines and fluoride because Moses did not have any. Evil?

In the same vein, Bergman speculates that Sakharov wanted the rule of law as he supposed it existed in the West. Well maybe but convince me. Quote that phrase ‘rule of law’ from something Sakharov said or wrote. [Silence.] The ‘rule of law,’ let’s ask David Hicks about that shall we? Montesquieu evolved a theory of government that inspired the writers of the Constitution of the United States to divide and separate powers; Montesquieu reasoned from the British example where he thought it existed but in fact it did not. Nonetheless, the illusion bred reality. (With difficulty I will refrain from mentioning that smirking Queensland journalist who made a name nationally by misunderstanding the separation of powers doctrine. Such are media reputations.)

Jay Bergman

Jay Bergman

Even though published twenty (20) years after the fall of the Berlin Wall this book is a Cold War salvo. Every few pages another evil of the Soviet regime is described, denounced, and then placed in relation to Sakharov with some long bows.

There is virtually no science in the book after the early pages, and the science there is in inaccessible to this reader. The last chapter on Sakharov’s legacy which addresses exclusively his dissidence. Period.

I still do not know what made him a brilliant scientist.

Orhan Pamuk, ‘The White Castle” (1990)

Doing homework for the Turkey trot, ooops, tour, in October 2015. I read Pamuk’s ‘Istanbul: Memories of the city’ earlier, finding it well written but meandering, too much like life that.

This book is a fable, an Italian traveler is enslaved in Ottoman Istanbul in the 16th Century. His western knowledge, particularly anatomy, sets him apart, first as a doctor and later as an engineer.

The pasha who owns him gives him to Hoja, because the two men, the unnamed slave and the master (Hoja), look a great deal alike. Hoja is a scientist-engineer employed by the pasha and the slave becomes his assistant. They work on several projects, including fireworks. The pasha strives for recognition from the Sultan, Hoja strives for promotion. Much striving.

One theme is identity given the resemblance of the two men and their incessant exchange of information for some years, some of it personal. Another theme is the resistance of the Ottoman world to change, as represented by scientific knowledge both imported from the West in the slave but also as generated by Hoja.

The third, the governing theme, is the master-slave dialectic. The slave becomes like the master first but in time the master becomes like the slave. At the end it is not clear who is narrating the slave who has assumed the identity of the master, or the master who pines for the slave (his European knowledge) as his alter-ego. Are Turks Asians or Europeans?

Then there is the unreliable narrator beloved of post modern writers but not readers.

Orhan Pamuk, Nobel Prize winner in Literature.

Orhan Pamuk, Nobel Prize winner in Literature.

But I fear that it is not particularly interesting to read. It is well written but seems lifeless, as though the plan was drawn up on a white board and then executed in neat chunks. The author is aloof, detached from it all framing the story as the finding of a third party.

‘Double Entry’ (2012) by Jane Gleeson-White

The subtitle of this book is ‘How the Merchants of Venice created modern Finance.’

Yep, this is a book about the thrills, chills, and spills of accounting and accountants, the thrills of receipts, chills of ledgers, spills of debits, and that is just the beginning! Economics is the dismal science, and accounting is its dreary cousin.

In 1986, according to my notes, I read Fernand Braudel’s ‘Capitalism and Material Life, 1400–1800’ in three magisterial (a code word for large and long) volumes. Braudel asserted in passing that the invention of double entry bookkeeping generated capitalism in Europe, first in Italy and then as Italian banks expanded northward to Amsterdam in Europe as a whole. At the time, I asked an accountant upstairs what double entry bookkeeping was, and he invited me to attend his twenty-seven lectures in Accounting 101 to find out. Some people always want to start way back at the beginning.

I tried again a few years later when I asked another accountant, who answered, in exactly 50 minutes, a lecture. That was simultaneously TMI + NEI or Too Much Information and Not Enough Information. None the wiser, my interest withered. But the ground was covered, as lecturers like to say.

Then one day I came across this title. The blurb promised that it would reveal all about double entry bookkeeping is. I took the bait! Who wouldn’t? Here is what I learned.

The Crusades created first mass tourism through Northern Italy which bought vastly increased demand for goods and services. Enterprises flourished to take advantage of the market opportunities these tourists offered, and so Italy has since remained. The Crusaders, those that came back, brought many things with them apart from saintly shin bones that they acquired from enterprising Arabs, they also brought back Arabic numbers.

Venice made sure it got a piece of the tourism action both ways, and the tourist boom it got put it on the map to stay since then.

Mathematics evolved thanks to those Arabic numbers, though it was resisted by the Catholic Church which saw evil in Arabic numbers. Multiplying and dividing was regarded as black magic. Sounds like an analysis by Fox News today. Ignorant and proud of it!

Though very Catholic, the authorities in Venice were pragmatic enough to tolerate Arabic numbers, despite papal fulminations. (Presumably some gold changed hands to buy the silence of the local prelates.) Indeed, Venetian authorities encouraged sound book-keeping, the more prosperous businesses are, the more taxes are due; the more accurate records are kept, the easier it is identify the taxes that are due and collect them. On this reasoning, the Venetians also invested in education! Hmm, has not quite caught on that one. Smarter, more well informed people make better use of their resources and opportunities to solve problems. This is still a new idea to some governments today, it seems.

Moreover, the Venetians licensed the publication of books about mathematics that spread the word through the Mediterranean world. Indeed because of its relative tolerance and stability it became a centre for book publishing as Amsterdam was to become later. Some of the earliest mathematics books published in Venice were applied mathematics aimed at book-keeping, says our author.

After all that background, what is double entry book-keeping? Good question, Mortimer! The essence is that each transaction is recorded in two entries, one called ‘credit’ and the other ‘debit.’ Wake up! ‘Credit’ and ‘debit’ are not used here in their ordinary meanings. (Those conscripted to use Spendvision will realise that there is nothing intuitive about accounts.)

Prior to double-entry book-keeping (hereinafter, DEBK) merchants, nobles, tradesmen, households did not keep accounts of any kind. I expect most of us still run the business of our daily lives like this.

Those that did keep records before DEBK, made notes on scraps of papers as reminders when something had to be followed up.

Most of us do a little book-keeping, say when keeping receipts for business expenses to submit for reimbursement from the firm, or to support business deductions on income tax. Either when submitted or at the end of the tax year we categorise and total these records. That is a primitive form of book-keeping. Corporate credit cards perform some of this record keeping for business expenses.

Before DEBK, the more careful merchants, especially those with larger volumes of transactions, began to write them down in a single list, e.g., of things bought and things sold. A month later it would be hard to find a particular transaction in that list, undifferentiated and without annotation. First came annotations which took the name ‘memorandum.’ These memos were sorted and entered again in a journal (a term still used in accounting), and finally in a ledger.

DEBK nests in a ledger with a T making two columns that are still to be seem in ledger books at Officeworks, Staples, or OfficeMax.

If I have $500 in my pocket then I have a debit against my capital of $500 and a credit in cash of $500, ergo two entries.

I know there is a lot more to it, but like all those accounting students I find it hard going.

The book goes on to claim that DEBK is the key to the whole of capitalism because someone said so. A lot of someone’s are cited, but…. Hold on! Slow down! Wait a minute!

The author shows that many people talked about and praised DEBK from, say, 1500 on, but not once, not ever does the author show that it improved business practice, was associated with greater productivity, led to more revenue for Venetian purses or anyone else’s. In short, there is nary a (factual) word about impact. It is all very Cultural Studies (a phrase I always shudder to hear, let alone type) to suppose that talk is reality and that reality is but talk. (Didn’t those Cultural Studiest ever mean a Lying Blackfoot? [You either get it or you don’t.]) Everyone praises Christianity, but it is seldom practiced with the fervour with which it is praised, even by those who praise it most, i.e., members of the Tea Party.

To a jaded reader (me) the best chapter then is the penultimate one on accounting scandals. Whew! What a list: Enron, Royal Bank of Scotland, World Com, HIH, One.Tel, ABC Learning, and that is just in the very recent past with an emphasis on some of the small potatoes of Australian examples. Of course when the potatoes are all one has, they are not small. Despite Australia’s sorry experience, it has more accountants per square dollar than either the United States or Kingdom (p. 153).

The author carefully alludes to the string of examples of accounting firms, which trade on their reputations, signing off on accounts of such corporations as those above a few days before the house of cards falls, and much to everyone’s surprise the piggy bank is empty, including the pension fund.

It does make a punter like me wonder what the point of it all is. (Yes, I thought of Foucault.) Have rules become so complex that a clever and determined villain can use them to hide the trail (in some cases for years)? Do more rules create more loop holes, black spots, grey areas, and trees to hide the forrest and just generally make it easier to play hide-and-seek?

For a couple of years I served on an Institute of Charted Accountants committee that enforced professional ethics on its members. The rigour of the proceedings of this committee, the take-no-prisoners attitude of its professional members (I was a lay member) was all very impressive, but all the cases (documented sometimes in hundreds of pages) were about the date of a membership re-newal to the Institute or something else on that level. Was the postage stamp correctly squared on the envelope, is what I silently thought sometimes. (Yes, it was that long ago that postage stamps were relevant.) Such tiny ants were destroyed with titanium tipped warheads! Ouch! Inevitably, the accountants involved were sole practitioners who were humbled before this pitiless tribunal. Meanwhile, the major accounting firms in the same building were signing off on the accounts of the likes as those above. Go figure.

In this world, the mud seldom sticks. The author describes some of the subsequent careers of many of the major players in the scandals above. At a corporate level the accounting firms that approved the accounts of such corporations change their logos and web sites, a few partners take the money and run, oops, retire, and the firms continue to dominate not only the market for accountants but also for consultants to government and more. One fears the same people who brought us the last corporate collapse are now happily advising governments on the next one. No mea culpas can be heard.

Like tools, rules can be used for good or ill to be sure. But independent audits are supposed to deter and detect some of the ill. Maybe they do, but that does not make the headlines.

Tidbits, there are a few. The CEO of the Royal Bank of Scotland CEO presided over the creative accounting that led to its near-death experience got a golden parachute of £16 million paid for by the ever generous British taxpayers (p. 197).

The high and mighty behemoth Arthur Andersen started in 1929 as a cleanskin firm which would ferret out cheats, and died in 2002 of the same poison. Well do I remember once getting told off by a very proud Andersenian about the irrelevance of ethics education in business degrees.

By the by, Enron started in Omaha where it trod the straight and narrow, but when it moved to Texas, well it crossed more than a state line, thus confirming some deeply held prejudices of mine.

Jane Gleeson-White

Jane Gleeson-White

As to the book, there is too much background and too much repetition and not enough focus or exposition of essence of double-entry to my mind. I still not sure what it is, so don’t ask.

‘Copyright’ (p. 78), no I do not think there was any intellectual property, but rather a license that permitted publication (i.e., passed by the Church censor and the Venetian censor). Copyright protecting the author’s intellectual property is centuries in the future.

A word is used that I cannot find in a dictionary: ie (p. 94). Even the spellchecker thinks it should be i.e. but not in this book.

There is a reference to Aristotle reviling interest on borrowed money but no text is cited (p. 96).

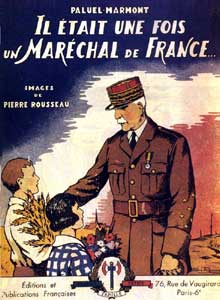

‘Parades and Politics at Vichy: The French Officer Corps under Marshal Pétain’ by Robert Paxton (1966).

In 1931 the French army was the largest, best trained, most modern in equipment with a wealth of strategic intelligence in a large and able general staff joined to the leading airforce of Europe and a large navy with newer and more powerful warships than England or Italy. In addition the French Army had those kilometres and kilometres of tunnels, bunkers, turrets, gun emplacements, tank traps, endless buried telephone wires and underground cities of the Maginot Line. To members of the general staff of Germany, of Spain, of England, and of Italy, France was an impregnable fortress. Moreover, it had an even larger colonial army spread around the globe from New Caledonia to the Caribbean. In particular its officer corps was its pride. It was drawn from all classes of society, promoted on merit in a system that prized intellect.

It was altogether impressive, this army, and yet less than a decade later during five weeks in May 1940 this army was comprehensively defeated. So total was the defeat that it was embarrassing. The defeat was as much psychological as material. French troops fought with each other in the rush to surrender. Units far from the front abandoned their arms never to touch them again because of rumours of a truce before the first radio broadcast of a ceasefire. Officers, it was said, surrendered as quickly as possible so as not to miss lunch. Censors tried but failed to suppress pictures of lone Germans herding thousands of apparently willing French prisoners along. This moral collapse turned the army into a mob by the thousands. When the German burst from the impassable Ardenne forrest, the French army fell to backbiting and backstabbing at all ranks. For their part staff officers in Paris denied responsibility and knowledge of anything and everything in some squalid episodes.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

Yet apart from some volcanic fighting in Belgium and around the Pas de Calais (Dunkirk and Ostend), the defeat resulted in relatively few French casualties, making it all the more surprising, and all the more embarrassing. In fact, French Army emerged from the defeat largely intact, though its members were divided, dazed, confused, isolated, dispirited, and exhausted. There is plenty of newsreel footage on You Tube. Have look.

Perhaps the analogy is to victims of a mighty car pile-up on an expressway.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

Blind-sided, a gigantic wallop with noise and shrapnel, and than another and another as the pile up continued. Much noise and confusion but few killed or injured. Yet all are dazed and confused.

This book is a study of how one set of the victims of that crash, the officers of the French army, responded to the catastrophe. It is a subject that takes study, because the recriminations at the time and since have been a blizzard without end, as blame as been laid this way and that, often with no other evidence than the unshakeable conviction of prejudice. In fact, it is perhaps the kind of study best done by an outsider who is disinterested in the matter. This book is based on archival material, publications of the day, interviews with participants, and, inevitably, the river of memoirs protagonists wrote to justify themselves. It is impressive to see how much microfilm of contemporary records and reports in German and French the author worked through to find the confirmation or disconfirmation of assertions that in other books are taken as read. Through this minefield Paxton picks his way with care and sound judgement.

What prompted my interest in this study was the realisation, born of reading about this period, that the chain of command in the French army survived the triple debacle of June 1940 and remained in place for the use of the Vichy regime both France and in the colonies, triple in the defeat, the surrender, and the humiliating peace.

Remember, that this army was deployed around the world in French colonies, territories, protectorates, enclaves, embassies, and missions – most particularly in Africa and the Middle East but also in the Caribbean, India, Latin America, and Oceana, including New Caledonia, today a one hour flight from Brisbane.

As discredited as defeated France was, the colonies held fast to it in this dark hour despite the clarion call from London on 18 June, when Charles de Gaulle made his first radio broadcast in the name of France Libre. Likewise, the officer corps in France also obeyed orders to return to barracks or comply meekly with capture and imprisonment. As German archives show, they were themselves surprised at the speed and scope of the capitulation and unprepared for it.

Even as two million French prisoners of war were being entrained to Germany, the remainder of the French army began to demobilise itself. While de Gaulle shined a light, in the first months few officers followed it. This is all the more remarkable considering the residual anti-German sentiment throughout France and most particularly in the army after the bloodbaths of World War I, which had led to the development the formidable army described at the outset.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

Paxton’s focus is not on the defeat but the aftermath, though he does set the scene by showing how in the years after 1931 the strength of the army dissipated. There were disputes within the army over strategy and tactics that took the form of bureaucratic backstabbing and career blockage to new extremes. Charles de Gaulle was himself one of the victims of this battle.

Though French tanks and fighter planes were technically superior to their German, Italian, and English counterparts in 1939, the doctrines that dictated their use did not exploit the capacities they had: One example, Renault heavy tanks were technical leaders, and those the Germans captured were later used to good effect on the Russian front in the following years. But French army doctrine spread them very thinly through infantry regiments as mobile block houses for static defence. They were not grouped to give weight and supporting fire power in attack. The Germans, at the time, had lesser and fewer tanks but made far more effective use of them. The same could be said for aircraft. It is also true that often the French forces outnumbered the attacking Germans, but the tactics of the Germans with tanks and aircraft overcame the numerical advantage the French had. The French also enjoyed the advantage of shorter and interior lines of communication but again German tactics cut these by attacking roads and bridges from the air. The French airforce doctrine conserved assets and did not attack German ground targets.

Even more corrosive were social attitudes of those born to the army, and their scorn for parvenus, including Jews that had entered the army during the Third Republic, especially under the Popular Front government. It went beyond the usual snobbery or cliques one must expect and included systematic efforts to degrade, discourage, and drive such undesirables out of the army. There were many little Dreyfuses victimised in a hundred small ways for the lack of a ‘de’ in the name or the presence of ‘berg’. Contrary to the post-war legends there was little liberty, equality, or fraternity in the French army by 1939.

After 1931 successive governments cut defence spending, as did General Phillipe Pétain, when he was minister of defence, and cut it again, and again as the Great Depression spread. As the ordeal of World War I receded from memory, an historic anti-militarism in French society, a child of the French Revolution when the army was the instrument of royal oppression (and it was again with the Napoleons and restored monarchs), re-asserted itself. Parliamentarians not only cut military budgets but they boasted and bragged about it, including one Pierre Laval. In the name of liberty, conscription was qualified by twenty pages of exemptions and exceptions, while the overall length of service was progressively shortened. A standing, professional army was perceived to be a greater threat to society than a foreign enemy by many ideologues who came to prominence in the Popular Front era of the Third Republic. It is also true that the Communist Party of France, following explicit orders from Moscow, disrupted French defence industries by strikes and sabotage and sheltered those fleeing conscription.

Though French generals said they were ready for war in 1939, despite later denials, the record is clear. It is equally clear that when the German offensive struck they were among the first to show the white flag. To review the last days of the Reynaud government as it fled from Paris, is to conclude that the generals gave up the fight before the politicians did. Prime Minister Reynaud himself was prepared to take the Government into exile and continue the war, as the Dutch, Norwegians, and Danes had done, but the generals, including Pétain advised him to surrender not just the army but the government itself. Reynaud could not bring himself to do that but he bowed to the majority of his cabinet and deferred to Pétain to seek terms of an armistice. Instead Pétain capitulated, precipitating generations of debate about the legitimacy of his initial government.

Later, of course, the generals blamed the politicians, but that is hard to credit. Start with the commander in chief of the field army, Maurice Gamelin, who set up his headquarters in splendid isolation from the front lines in a place chosen more for the wines in its cellar than for its communication or access to the armies he commanded. Read this sentence slowly: After nine (9) months of war, he had in his headquarters no telephone in May 1940.

Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gamelin

He sent and received messages by car and motorbike along country lanes but few roads ran to the border where the army was emplaced. He later explained his inaction in the crisis by saying that he did not know what was happening. Hmm. If communication with Gamelin was slow when nothing was happening, once the front broke he was a hard man to find. (Radio was too easily intercepted for use and unreliable in the heavily forested area and jammed by Germans.)

I referred to doctrines before. Here is another example. The French General Staff had slowly and painfully negotiated an agreement with Belgium before the war to form a line of defence on the Dyle River in Belgium. This Dyle Plan allowed three (3) weeks, 21 days, for the French Army to take its positions along the River Dyle. Care to guess how long it took Germans to breach that line? Three (3) days. Once that happened the French Army had no plan of operations. They had thought of everything except a Plan B. (By the way the British Expeditionary Force was part of this plan and was thus left without a mission.)

Overarching themes:

Officers from general to lieutenants denied the defeat by blaming politicians, British perfidy, spies, lazy conscripts, unpatriotic civilians….women who smoked, protestants, secular education. The list went on. Only the army was blameless for its defeat.

Military contempt for parliamentarians and the Army’s early effort to dominate the Vichy government. Civilian control was only established in April 1942. Apart from Maréchal Pétain himself the Vichy government was dominated in its first crucial months by General Maxime Weygand and then later for longer periods by his navy rival Admiral François Darlan.

Backstabbing, cliques, career opportunism were rife in the very hard circumstance of the armistice army that the conquering Germans permitted. This personal struggle is most well documented at the most senior levels of the army but it was not confined to the top.

Vichy played off Germany against Britain and vice versa by trying to be neutral, not so much in Vichy France itself, but in the colonies, especially those of strategic import like Dakar, Damascus, Djibouti, Diego Surez, Noumea, Oran, and Bizerte. To keep the Germans out of the colonies the Vichy regime defended them from British incursions. To keep the British from occupying a colony there was the spectre of a German response.

There was an effort to use the National Revolution of Vichy to enhance the status of the army after its humiliation. The new curriculum emphasised patriotism and physical fitness and left little time for science. Girls were encouraged to leave school at puberty.

The benign Pétain.

The benign Pétain.

The fate of two million French prisoners of war in Germany preoccupied some officers to the exclusion of everything else and was ignored by many others. These prisoners included all ranks including generals like Giraud, Juin, and others.

Inter-service rivalries that pitted the influence of the army against that of navy, and the navy won very often because it had all those lovely ships which the British wanted and the Germans did not want to Brits to get until November 1942. The army was discredited by its collapse.

The near thoughtless compliance with the purge of Jews from the army, navy, and air force. Likewise the German efforts to identify and seize Germans in the French Foreign Legion is a sorry story of compliance.

Most officers obeyed Vichy because the regime was congenial, not out of duress or desperation. Indeed those officers forcibly retired to reduce the size of the Army clamoured for re-admission.

Vichy officials reluctantly agreed to many German demands but moved slowly to comply. It might take six months to get agreement from them, only to find it was another nine months before they took the first steps. There was a lot of this kind of passive resistance. It is not easy to trace its origin. At times both Pétain and Laval expressed anger at the slow movement of their government, but at other time this pace suited their efforts to keep Germany at the negotiating table.

The Vichy regime presented itself to France and to the world as the sovereign government (of what was left) of France. See, for example, the newsreels at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU61J_xXBAE

(Cut and paste the address into a browser.)

The army’s chain of command held despite the colossal shocks of May and June 1940. By and large the French army from generals to lieutenants accepted Pétain as the government of France and obeyed his orders. But it is important to realise why that chain held despite the unprecedented jerks on it. (It might have been a different story without Pétain. A government with only Pierre Laval at the top, well that certainly would have been less compelling to most officers.)

Officers had responsibilities; they were not free agents. As long as those responsibilities remained and made sense, they stayed at their stations. Paxton makes this point by analysing the officers who joined de Gaulle’s France Libre. They numbered several hundred and then thousands and invariably they were officers who did not have command of men who were dependent on them.

De Gaulle himself is an example. He had been relieved of his field command in May and appointed an under-secretary for war in the Reynaud cabinet, and then sent back and forth to London several times to gouge greater effort from Britain.

The officers who first joined de Gaulle fell into these categories: retired, on unattached duties (ill or convalescing), attachés at embassies around the world (particularly Latin America), staff officers who did not command subordinates, on special assignments (e.g., as couriers, liaison, or missions abroad). These officers were free(r) agents than those with dependents, i.e., subordinates. They came from metropolitan France but also from the colonial forces. Of course they may have had families to think about, too.

While nearly all officers at French embassies in the the Americas saluted de Gaulle’s flag, not every retired or convalescing officer did. The second criterion that Paxton suggests was decisive is access. Retired or unattached officers who had only to travel a short distance to join de Gaulle, were more likely to do so. Many officers on special assignments were already embedded with British forces as liaison or couriers along with scores of others in the United States and Canada on a variety of missions. Some colonial officers had only to walk across the street to a British consulate to get passage to London. But retired or convalescent officers in Lyons or Metz had no such access and so joining de Gaulle may well have never crossed their minds. Later the fear of reprisals against one’s family in France held some officers in check. Others adopted noms de guerre to avoid such reprisals.

In time as the Vichy regime lost creditability. The unopposed Japanese seizure of Indochina shocked officers far and wide but most of all in Indochina, from which some intrepid souls found a way to abscond and travel, slowly, to England. German setbacks like the stalemate at Stalingrad encouraged others to abandon Vichy neutrality for the opportunity to return to the war effort, e.g., those garrisons in India (a surprising large number). While some officers were staunch themselves they turned a blind eye to the departure of junior officers, forging roll calls to fool German supervisors. Yes, there were German supervisors throughout the French colonial Armistice Army, as well as the Armistice Army in Vichy territory.

Officers in the Armistice Army in Vichy also acted in secret. Rather than turn over all weapons and ammunition to the Germans, they hid much against the future. One trove, scattered in numerous caves, mines, commercial wine cellars, abandoned barns consisted of thirty-nine (39) tanks! The tanks had been disassembled and crated, marked as agricultural material and salted away.

When American troops landed in Morocco and Algeria in November 1942, the veil fell. The Vichy chain of command was by then muddled. Mistrust, suspicion, fear of reprisals from either Germans or Gaullists, residual anti-German feeling, loyalty to Pétain, inter-service rivalries between the navy and the army, tests of will between civilian control and military, all had grown over time and reached new heights; this brew bubbled, collided, mixed, leaked when reality of an Allied invasion occurred.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

Contradictory orders were issued one after another by a single commander as information came in or was discredited. Conflicting orders came from civilian and military authorities, who then disputed each other’s right to give orders. Generals disputed the authority of other generals to give orders in the crisis. Messages from Vichy said one thing and the local representative of Vichy said another.

Because communication with Vichy was disrupted, the chain of command was altered, but not everyone got the message about the change. Some commanders got orders from generals they had never heard of. Confusion was the result and that led often to inertia and paralysis. Though the reaction of soldiers when attacked is to reply in kind, there was no decisive leadership and the will to resist dissipated within hours. The soup of conflicting orders, contradictory orders, the unabated undermining of rivals confused the matter all the more.

One example is a captain with a company on the beaches at Casablanca received orders from a his colonel to greet the arriving Americans as allies, and almost simultaneously orders from his major to fire on the landing parties. Faced with this contradiction, the captain took his men back to the barracks. The colonel and major were each passing on orders they had received.

In this mire, the castle was Algiers where the headquarters of the French colonial forces in North Africa was located. The conflict and contradictions were played out there with full force. In addition the American sponsored alternative to de Gaulle, Henri Giraud arrived with his immense prestige as a soldier and his childish incomprehension of the political situation, along with the American commander General Mark Clark whose campaign had already fallen behind schedule. In addition, François Darlan, Vichy Minister of Defence and commander in chief of the French navy was in Algiers on private visit to his ill son. The clash of these egos was seismic. The French would not agree among themselves, still less with Clark, but he had the bayonets.

At stake in this opera in Algiers was nearby Tunisia. It was the frontier between Vichy North Africa (and now the Allies) and Rommel’s Afrika Corps in Libya. The Germans wanted to use Bizerte as a port to supply Rommel. Vichy neutrality forbade that. When it became clear that the Allies had taken over in Algiers, and when de Gaulle arrived there and ended the fruitless negotiations with Vichy officials, the Germans stopped asking and started taking. In response the French troops in Tunisia turned on the Germans. As soon as this switch was reported by the Germans to Vichy, Pétain relieved the Tunisian commander, General Alphonse Juin, who ignored the order on the assumption that Pétain’s hand was forced by Germans. The chain of command snapped at long last.

Now the Armistice gloves were off from Morocco to Tunisia and Djibouti, and French officers along with their commands in these stations joined the Allies as speedily as possible. Within a few months every French colony was aligned with France Libre. Thereafter, General Juin’s 100,000+ man First French Army led the way in the Allies’ Italian campaign. At the bitter end, Free France had 250,000 soldiers in the field in Europe.

The necessities of war brought Great Britain and Vichy into conflict to be sure. While Hitler had promised not to seize the French fleet, he was not a man famous for keeping promises. While French admirals swore not to let their ships go, would they be able to resist at the moment of truth or would they, like so many others, be overwhelmed by the Nazis?

Noteworthy, but not mentioned is that the Armistice Army was never used to enforce order in any sense. This army did not round up Jews. It did not kick in doors to arrest trade unionist. Its parades were not designed or intended to intimidate onlookers, in contrast to German parades in France. Rather these parades were intended to boast morale in the ranks and in the viewers.

I do wish the author had included some kind of chronology of major events with a comment on the fallout of each as I did above.

I do wish the author had included more numerical information, i.e., data about the military formations discussed. Numbers are mentioned at times, but a table or graph would be more effective.

I do wish the author had more systematically distinguished the metropolitan Armistice army from the colonial Armistice army, and then offered some general account, complete with tables, of their size and distribution.

Only a few sentence end with conjunctions in this book, however. This regrettable tendency is much in evidence in another Paxton’s books.

‘Pierre Laval and the Eclipse of France, 1931-1945: A Political biography’ (1968) by Geoffrey Warner

Laval was the dark prince of the Vichy Regime (1940-1944).

Pierre Laval in 1931