‘Jean?’ who you ask. Jean Monnet (1888-1979). He ought to be called ‘The First European,’ since he is widely regarded as the mid-wife of the European Community. Quite an achievement for someone who never held an elected office and who was never a civil servant. Yet by wit, tenacity, wisdom, patience, a vision, an appetite for data and facts, a network of friends and acquaintances all over the world, he kept moving toward a European union, and he got a lot of other people to move in that direction, too, including Charles de Gaulle.

In 1938 the French Prime Minister sent him on a special diplomatic mission to the Washington D.C. In 1940 Churchill gave him a British passport and sent him on a special diplomatic mission. In 1943 Roosevelt entrusted him to be his representative in Algiers.

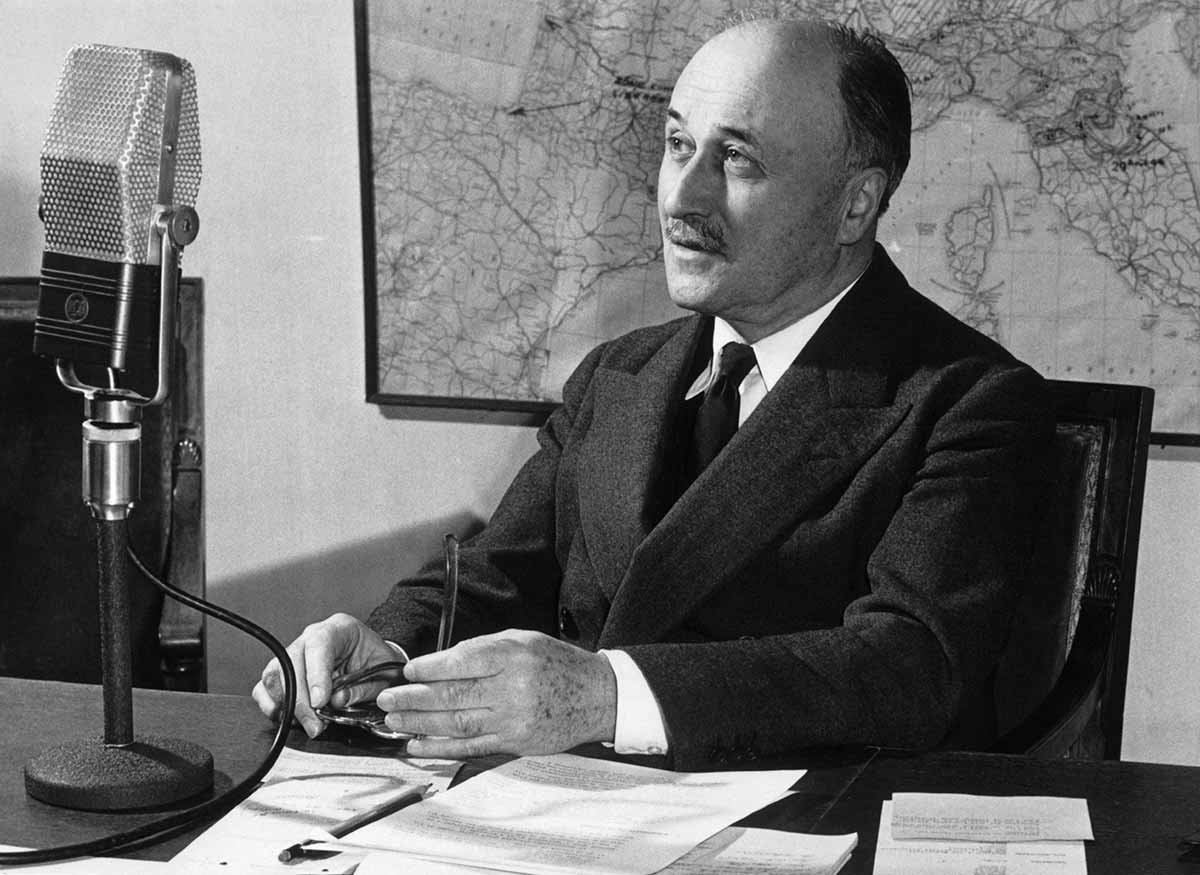

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Internationalist indeed. This was just the beginning.

In Monnet’s mind European union was the means to the bring of enduring peace to Europe. He was born into a wine family in the Cognac and began working for the family company at 16. At that age he learned enough German to sell barrels of brandy to German buyers. Later as his father innovated and expanded the business, he sent young Jean to London to learn English while selling brandy. There he found his best single customer to be the Hudson’s Bay Company of Canada which bought in volume for national distribution. In time the Bay hired him, with his father’s encouragement, and he spent time in Canada, and from there the United States.

Asthma kept him out of the army in World War I, but, inspired by his experience with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he proposed to the French government that it join with Britain in a consortium to purchase not just war materiel but everything else, too, including the shipping to transport it, and the bank loans to pay for it all. An Inter-Allied Committee evolved out of this suggestion and Monnet was its executive assistant, and in no time at all he ran it in everything but name. There were many conflicts on this committee and Monnet was the one who never gave up, who stroked egos, who broke the conflicts down into a small pieces to find common ground, who developed the spreadsheets to demonstrate the priorities…. This committee was successful beyond anyone’s expectations. By the way, it was a small committee of four (USA, England, France, and Italy) and that was another enduring lesson. Keep executive committees small.

Toward the end of the war he left that committee and worked for Herbert Hoover in war relief for Belgium and France in that Herculean effort where twenty hour days were the norm.

At the end of World War I he went to work at the League of Nations, serving there for three years as an international public servant. He passes through Frank Moorhouse’s superb novel ‘Grand Days’ set in the League.

Lured by the business opportunities offered by friends in the United States he moved there and made millions of dollars only to lose it all, as did so many others, in the Great Depression. He went from multi-millionaire to pauper in a few weeks. His passage back to France was paid by friends, including John Foster Dulles.

Never one to sit idle, back in France he received an offer from Chiang Kai-shek’s government in

China to set up and import-export bank in Shanghai. One of his League of Nations colleagues had recommended him for the job. He took it and succeeded, where several others had already failed. Later a dynastic power play in Madam Chiang’s family pushed his patron out of the bank and Monnet with him. His greatest achievement in this venture had been to convince the Chiang government that it had to re-pay all outstanding debts before trying to borrow more. This was a hard sell and it took a couple of years. He also made quite a profit from the three years he spent there.

He married an Italian woman who had left her husband. No divorce was possible in Catholic Europe. Both Monnet and his wife-to-be became Soviet citizens because divorce and re-marriage there was easy. She travelled from Switzerland to Moscow and he from Shanghai and there she divorced her husband and married Monnet. Reds! How did he live that down in the Cold War? This book sheds no light on that.

When he returned to Europe Monnet hatched a plan for France to buy airplanes from Canada. These airplanes would be assembled in Montréal from airframes and engines manufactured in the United States, in a work-around of its policy of neutrality. In the course of devising this plan Monnet had private meetings with President Roosevelt at Hyde Park.

The French capitulation occurred before those planes were delivered, 5000 in all, but Monnet on his own responsibility signed them over to Great Britain. For this act, and many later ones, the Vichy French regime charged him as a traitor. De Gaulle did the same, by the way, with military equipment intended for the French army in 1940: Gave it to Britain.

Churchill’s desperate gesture to keep France in the war in May 1940 after Dunkirk was to create a union government combining France and Great Britain as one. Churchill offered to defer to Paul Reynaud as the head of such a government. Quel beau geste! In London Monnet wrote the text for Churchill. The idea was that then Reynaud could take the government out of France to London and the French fleet and France’s considerable colonial army could be brought into the war. Reynaud could not convince his cabinet to continue the struggle and the moment passed.

Though Monnet supported de Gaulle’s effort to keep France in the war, he feared basing it in London would compromise it in the eyes of Frenchmen, which it did. He tried to convince de Gaulle to move to Algiers, and so remain on French soil. De Gaulle did not, and probably wisely. To move Free France to Algeria in 1940 or even 1941 might have meant capture by Vichy. Moreover, even if Algiers could be won over, location there would mean foregoing the material support Great Britain offered in London.

In 1943 Monnet was thinking ahead about European reconstruction. In Washington he used his business and political contacts to talk incessantly about the necessity of economic reconstruction to ensure social stability, including one lunch at the Pentagon with George Marshall. Monnet was responsible for American Lend-Lease supplies going to Free France. In fact, at the times he was the de facto American administrator of Lend-Lease going to Free France, and the de jure French manager of the supplies obtained. In this role he was a tyrant for propriety, insuring there was no hint of the graft, corruption, or profiteering that marked so many Lend-Lease operations elsewhere. This propriety made later Marshall Plan funding easier to justify.

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

The historic conflicts between France and Germany, in the industrial age, had focussed on the Saar, Ruhr, Pas de Calais, Alsace, and Lorraine because there is where the coal and steel was. In 1943 Monnet was drafting plans to internationalise these regions under joint control of three or four countries. This is the seed of the European Coal and Steel Community, which later gave birth to the European Community. Monnet’s idea was to take the means of modern war out of the hands of a single country to put them into some kind of transparent international protectorate.

He was the author of the Schumann Plan that embodied this ambition and led to ever greater French and German collaboration and European unity. It was not easy going, and it took nine complete versions to get a plan that both France and Germany accepted since it involved a diminution of sovereignty. While others gave up and quit, Monnet persevered. The European Coal and Steel Community became the first voluntary European entity since the Holy Roman Empire. I omit the League of Nations because of its origins in Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on it as the price for the Treaty of Versailles to end World War I.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

No sooner was the ink dry on the Treaty of Rome in 1957 which marked the beginning of the European Common Market, European Community, European Union of today, than Monnet began to talk about financial integration. He set up an Action Committee of private citizens, partly funded by foundation (including Ford and Rockefeller) grants, to organise seminars, radio lectures, publish discussion papers on financial integration, brief journalists which in time came to be a common currency, the Euro.

As successful as he was, Monnet had failures. Try though he might, he could not convince Roosevelt to recognise de Gaulle’s Free France as the provisional government of France in 1943.

Monnet also proposed a European army, partly motivated by the Soviet Union’s machinations at the time of the Korean War. This, too, failed. His aim was to contain German re-armament within such a pan-European army.

Another failure was Euratom which he proposed to make nuclear research European and so not put to military use by a single nation. France itself would not agree to this limitation, though the initiative is in the genealogy of CERN in Geneva today.

How did Monnet do all of this? Most of all he was a salesman. He loved big ideas and no idea was too big to interest him. He did not think of reasons why a big idea was impossible. As he emerges in this book, he is not reflective, nor introspective, and certainly not given to self-doubts. The harder the sell the more energised he seems to have been. He was not a writer either. The many policy proposals and discussion papers were terse, and detailed in dot points, graphs, tables, maps, and charts. The text would be filled out later by others. His preferred method of exposition was discussion and he was a master of that whether in a seminar, at the podium, dinner table, or a seat on a train or plane. Every occasion was used to develop, test, and advance the big ideas.

How did he live? Often he was sustained by the grace and favour of friends and admirers. He had no fortune and long ago he had signed over his share of the family business to his brothers. The money he made in China was considerable but moving in the elite circles he did meant the best restaurants, the best hotels, first class passage on ships and planes. He exhausted that money soon enough. His service on one special mission after another, yielded living allowances and nothing more. When at 70 he slowed down, to live on …. a pension derived from his three years at the European Coal and Steel Commission and that is all. He agreed to write memoirs in return for a hefty advance which supported his last years.

His name is everywhere in Europe. On postage stamps, commerative medals, universities, think tanks, government fellowships, busts and plaques in foyers of EU buildings in Geneva, Brussels, and Strasbourg, and the like, and yet he remains largely unknown, ever the stage manager in the back while the stars tread the boards before the audience of history. Indeed his name can also be found in Australian universities and yet few could say more than a sentence about him.

Monnet cognac remains in the market though no member of the family is now associated with it.

The book is comprehensive and thorough with admirable documentation. It is far more interesting than the first biography of Monnet I tried to read. Perhaps because Monnet was not a leader and did not hold an office, there seems to be little drama or momentum in the book. To confess, as fascinating as the story is, I found it a test of will to finish reading it.

Aside: Roosevelt’s handing of all things French in the war seems to have been clumsy and ill-informed for such a master juggler. Roosevelt overrode his Secretary of State to maintain diplomatic relations with Vichy from July 1940 to November 1942. Roosevelt’s hand picked ambassador to Vichy recommended suspending diplomatic relations but FDR ignored this advice. Did Roosevelt hope that indulging Vichy would make things easier when the landings in Morocco occurred? It did not. Vichy ordered resistance and resistance there was. Ditto in Algeria. In Algeria the United States through diplomat Robert Murphy indulged the Vichy governor Admiral Darlan and tried to undermine de Gaulle. Darlan enforced Vichy’s anti-Semitic laws, arrested and deported to France enemies of Vichy, transported Jews to France for German death camps, and more while America officials and officers looked on. Even though by that time it was clear Vichy would not, could not open any doors to France when the invasion came to the continent.

Category: Book Review

Robert O. Paxton, ‘Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944’ (2001 [1971] )

A wall poster of General Pétain features in the opening sequence of ‘Casablanca’ (1942) and that film concludes with a bottle of Vichy water tossed into the rubbish bin. That’s about all I knew about Vichy France.

Pétain was 84

Pétain was 84

Whereas every other country Nazi Germany conquered was placed under direct German rule, France was not. The Vichy Regime, as it became known, by the terms of the Armistice was to govern all of France, even though the North was occupied by Germany. The Occupation was only military. Civilian life was the domain of the French government, temporarily located in Vichy.

Divided and dismembered France

Divided and dismembered France

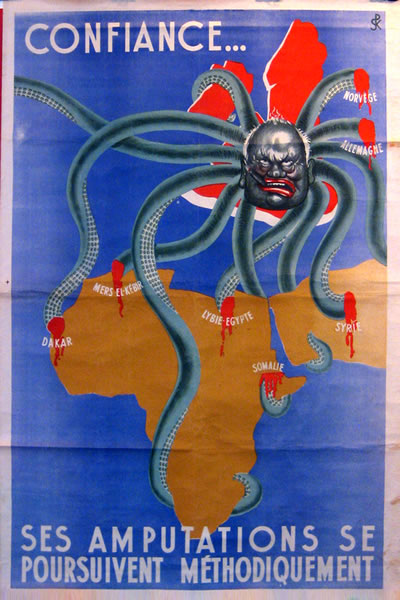

Among the overarching themes in the book are these: First, Vichy evolved as the war developed. It transformed itself, in part, and was later transformed by the Germans. Second, at the start Vichy earnestly sought co-operation with Germany, to which Germany was indifferent for a couple of years, until the tide of the war changed the calculus. Third, Vichy had nominal responsibility for the whole of France, i.e., including the Occupied Zone in the North and West for schools, hospitals, police, roads, and so on. Fourth, in practice France was divided into three not two zones, the third being Paris itself where the German presence was the greatest and collaboration was the most blatant. Fifth, the Vichy regime was internally riven by ideology, religion, region, and personality, united only by an abhorrence of the Third Republic and a willingness to work in Vichy. Sixth, Vichy’s commitment to retaining the Empire ran deep, hence the undeclared naval warfare with Britain, the defence of Syria and Algeria, and Vichy bombing attacks on Gibraltar. Vichy propaganda supposed Britain’s only war aim was to seize the French Empire. In this context Vichy propaganda portrayed General de Gaulle as a puppet for Britain to steal the French Empire away, which partly explains his intransigence in trying to retain every foot of the French Empire from Syria to Morocco.

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

Germany wanted France out of the war, and did not want a French government-in-exile to continue the war in any way. Why not? After all the Norwegian, Dutch, Polish, Belgian, and Luxembourg governments-in-exile existed and were of little moment.

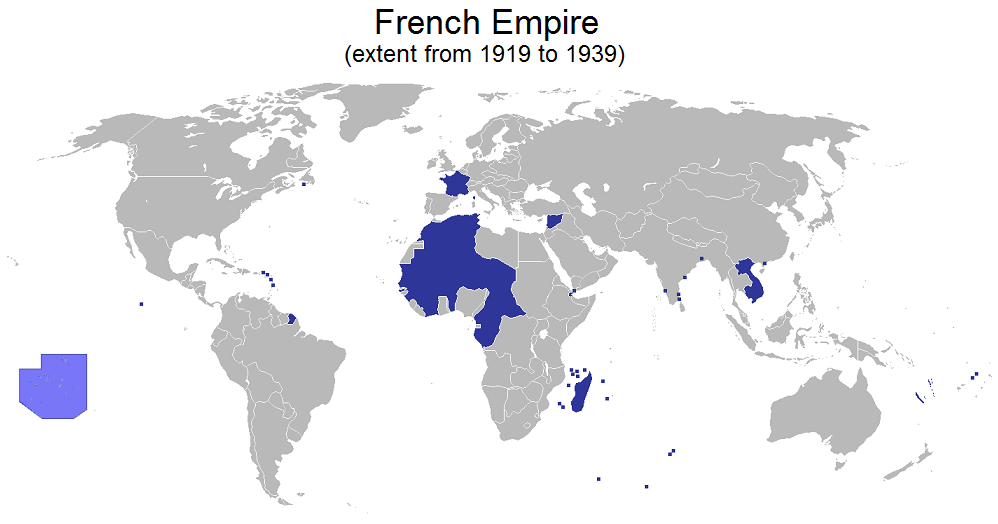

France was different because (1) of its proximity to Britain for the putative invasion, (2) its size compared to these others, (3) its navy which was second only that Britain, and (4) its colonial empire, particularly in North Africa – Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and the Levant. A united French government-in-exile might make a very large difference in one or all of these dimensions.

As to (1), in July 1940 the German plan was to concentrate on an invasion Britain as soon as air supremacy over the Channel was achieved, not on occupying and subduing every corner of France. Let the French govern themselves in everyday life, policing, sanitation, railroads, hospitals, water, roads, schools, and so. Call these matters administration. Of course, such administration continued in the other occupied Western European countries but run by Germans. Read on.

(2) The difference in France was size and location. German staff estimates of the troops needed simply to occupy all of France were considerable, let alone what would be necessary to subdue continued resistance in a rear-guard or guerrilla action in the Vosges, Alps, Pyrenees, Massif central mountains or the swamps of the Gironde, Loire, Rhone, and Saone rivers. It was best to make peace so that France could be used as a platform against Britain, and as a resource of food, men, and armaments. As it was the German army of occupation in France numbered a mere 40,000 for a population of 45 million, and most of those Germans were concentrated along the North coast opposite Britain. When resistance attacks began, that number increased and the overall calculus changed.

(3) The French navy was distributed around the world, though much was in French waters, not all. There were major elements in Africa (Algeria and Senegal), and there were 18,000 French sailors and more than one hundred ships in England in June 1940. Germany did not have the means of using the ships in French waters, i.e., it did not have the seaman and officers to man them, still less did it have a surefire way to recall the fleet from Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific. The best option then was to neutralise it by an agreement with the French government, i.e., the Armistice, to keep the ships out of the hands of Britain which might have the means to use them. Hence the fiction that Vichy was sovereign neutral. If and when Germany needed the ships, they would then be available. The fiction of French sovereignty kept the much of the fleet on ice for several years.

(4) Finally the colonies were a distraction to Germany. It had no means to occupy even those of strategic value, e.g, French Somaliland on the Red Sea, Lebanon and Syria (then French protectorates) with ready access to Middle East oil, or Dakar (Senegal) with its excellent deep water port on the Atlantic. Each would have been useful, respectively, to disrupt the Suez Canal, either secure Iraq oil or disrupt British access to it, and to base submarines in the Atlantic. Even so, Germany did not have the means (at the time) to do anything about them. Neutrality would be the best, immediate result to keep them out of British hands while the final battle for Britain occurred and allow for the possibility that later Germany would make use of them, brushing Vichy aside.

However, when Hitler turned east to the Soviet Union, then the demands on France changed, and would change again when the Allies landed in North Africa, expelled Germany from Tunisia, invaded Italy and drove it out of the war, and landed at Normandy. Each time, the German bear-hug on France tightened.

The 1940 Armistice allowed France, alone among the conquered European countries to retain a sovereign government beyond the daily administration alluded to above. France was divided into two zones and Vichy had about 30-40% of the country by either area or population. While much of France’s industry was in Paris and the north, Michelin tires, for example, was located within Vichy and several large manufacturers were in Marseilles and Toulon. The Armistice implied that once the war was won against Britain, the Vichy regime would be located in Paris and the northern Occupied Zone would dissolve. Meanwhile, Vichy received ambassadors from the United States and Canada and thirty (30) other countries, negotiated with Britain in Madrid for French assets, sold war matériel to Italy, imported food from Latin America, appointed new governors to its empire abroad … for a time.

Meanwhile, the regime was temporarily housed in the hotels of the spa town of Vichy. Why Vichy? Because nearby Clermont-Ferrand had the very best railway connections and Vichy itself had the most modern telephone exchange in France, connecting it easily to Paris, Berlin, Marseilles, and any where else. Moreover, one the most influential members of the Vichy Regime had major commercial interests there, and probably lobbied for the location, namely Pierre Laval.

By the Armistice, Vichy had administrative responsibly in the Occupied Zone, and near sovereignty in its Free Zone. Indeed, it maintained an Armistice Army of 100,000, unique in conquered Europe. That it existed, motivated many officers and men to be loyal to Vichy until November 1942 when it was disarmed and disbanded.

Though not stated in the Armistice, Paris quickly became a separate, third zone in everything but name.

Paxton convinces this reader that the Vichy regime attempted to use the situation to break with the past of France, and start the National Revolution to wind the cultural clock back. The first break with the past was the name. It called itself L’État Français and not La Républic Français. It repudiated the Republic and all it represented. It was a utopian moment when the discredited past burned away, allowing a Phoenix to rise. And because authority was concentrated in the executive, Pétain and the cabinet, with no carping, criticising parliament to be accommodated, it was a green-fields opportunity to (re)create a society afresh by dictate.

The Vichy Regime was Catholic not secular, agrarian not urban, insular not cosmopolitan. It did not celebrate the Rights of Man but rather the duties of a good Catholic to pray, work the land, procreate, and shun outsiders. On grounds that a religion brings order and calm it embraced Catholicism, though none of the principals of Vichy was ever religious, and certainly not Pétain himself, still less Laval. The school curriculum was changed and the Catholic Church invited to re-enter the classrooms from which it had been expelled after the Revolution. Science was de-emphasized. Curriculum committees set to work cutting French literature down to Vichy-size, big ideas out, duty and humility in. Girls were encouraged to pray and bear children for France. Withal, the author argues that Vichy was not fascist, but rather nationalist, nostalgic, and conservative. For example, its anti-Semitism was culture not racial. Hence the efforts of Vichy, ineffective though they were, to protect converted Jews.

Paxton shows in a great many ways that the Vichy Regime strove to be an active partner with Germany when it seemed that Germany’s final victory was only a matter weeks away. Again and again, Vichy took the initiative to expel Spanish Republican refugees, to identify foreign Jews, to surrender arms, to bomb Gibraltar, to turn over information, to oppose Britain in word and deed, and to excoriate de Gaulle. Later, by 1944 the tables had turned and Vichy was merely a German catspaw, but that was not the case in 1940, in 1941, in 1942, in most of 1943, and even in some ways in early 1944.

Phillipe Pétain headed the Vichy government, bringing to it little more than his name, as the victor at Verdun in 1917 and a reputation, in contrast to so many in World War I, for saving the lives of his men behind fortifications and not spending them in pointless attacks. He was 84 years old when he took over. German intelligence kept an eye on all things Vichy including Pétain himself, and its assessments repeatedly confirmed that the old man had his wits about him, though he tired easily in the afternoons. We should all be so fit at that age.

When the time came the Vichy regime made itself a German catspaw. To make work in the South it negotiated contracts for war matériel for Germany. When Germany demanded slave labour, Vichy conscripted it. When Germans retaliated for resistance attacks by shooting hostages, Vichy volunteered to do that, and in some cases exceeded the German appetite for blood, as both local and national authorities settled old scores, personal and political. Most of all it delivered up Jews ever easier. Once on the slippery slope, the only way was down and down into the levels of Hell.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

Paxton chronicles the infighting, careerism, exploitation, profiteering, undermining, conflicting personalities within the hothouse of Vichy, though he offers no explanation for the remarkable dismissal of Pierre Laval in 1941, who bounced back and exacted revenge on his real and imagined enemies. The seamy side of Vichy is well realised in some of J. Robert Janes’s krimies set in this time and place like ‘Flykiller’ (2002).

One of the claims of Vichy was stability. Unlike the volatile Third Republic where governments lasted six months at best, and often less, Vichy would be a rock, as Pétain was at Verdun. Vichy propaganda repeated that claim untinged by the fact that its was a government set to musical chairs with six ministers of defence in one year, and a parade of prime ministers (until the Germans put a stop to it): Pétain, Weygand, Laval, Flandin, Darlan, and Laval again in less than 2 1/2 years. The Third Republic had longer periods of ministerial stability than Vichy ever had. Rather reminded me of the Murdoch media where what matters is repetition not veracity. Pétain wanted to remain prime minister and tried to regain that post but lost in these manoeuvres Laval.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

This book also makes very clear just how very alone Charles de Gaulle was on the 18th of June 1940 in London and how alone he remained for quite a time, making his creation France Libre all the more remarkable. De Gaulle remained alone because the chain of command in the army and the colonies held, despite the catastrophes of the defeat, the surrender, the occupation, the dismemberment.

There are honorable exceptions to the unalloyed vanity, venality, and immorality of Vichy. General Charles-Léon Huntziger, whom Charles de Gaulle specifically invited to command Free France forces, chose to stay at his post to share the fate of his soldiers in captivity, signed the Armistice in that railway car, and then worked tirelessly on the Armistice Commission to secure the release of French prisoners of war by any and every means, and met with some success.

To end where we started with ‘Casablanca,’ the Governor-General of French Morocco, Hippolyte Noguès, held to Vichy despite his own expressed conviction that the Reynaud government should retreat to Algeria and continue the fight from there. This was soldier who obeyed orders, however distasteful. But when by the terms of the Armistice a German commission arrived to monitor the French troops there, he restricted the movements of its members, assigned them a police escort, insisted they wear civilian clothes, put them in poor accommodation, and tried everything within his limited powers to minimize their impact. ‘Casablanca’s’ Major Strasser would not have been allowed to wear his uniform, click his heels, drive around with a Wehrmacht guard, or start a bar fight. Not quite as accommodating as Louie Renault in the film. On the other hand, in 1942 when he was told, the day before, that American forces would land, he was ordered to resist, and he did for three days before surrendering. Not quite the romp show in ‘Patton’ (1970).

The book is informative, insightful, meticulous in the use of evidence, precise in drawing conclusions, and makes extensive us of German archives. It is also somewhat repetitive, which suggests more organisation is necessary, and there are annoying lapses in composition. Too many sentences end with ‘however,’ ‘moreover,’ and ‘of course.’ Far too many. There are also cryptic references to French history better suited to the seminar room. The author compiles some compelling data, especially in the final chapters, that is, quantitative, calories a day, total costs, tonnage of shipments, and the like, and these are presented as lists in paragraphs. While the presentation of evidence is welcome, this method detracts and distracts. Better to have presented as much of this evidence as possible in charts, graphs, and tables to give the reader a picture to put the detail into perspective.

Postage stamp catalogues feature stamps printed but not distributed by the Vichy regime for France’s far flung colonial empire. By early 1943 Vichy had lost contact with most of that empire, apart from North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco), and by 1944 all of that empire had gone over to Free France, with the exception of Indochina which the Japanese had occupied much earlier, despite the protests of Vichy. Germany made no effort to discourage this Japanese strategic move. Yet the stamps kept coming off the presses.

In a time of desperate shortages, when skilled manpower was at a premium, when printing presses were being broken up to be re-fashioned into weapons, when oil was a rarity, at this time the Vichy government had printed by the thousands in Paris those postage stamps for all of its lost empire. Almost none of those stamps were ever issued, that is, they not transported to Madagascar, Réunion, Nouvelle Caledonie, St Pierre et Miquelon, Guyana, or the Antarctic station. An example suffices. New stamps for St Pierre et Miquelon were issued six months after those strategic islands off the Atlantic coast of Canada had been occupied by an Anglo-Free France force. Reality did not intrude into the process, once engaged. Anyone who has worked for a larger organisation knows the truth of that fact.

Issued in 1943

Issued in 1943

Is this a case of bureaucracy gone mad? With the new constitution of Vichy the colonies had to have new stamps, so new stamps were produced regardless of the circumstances. Possibly. Another explanation presents itself, though, continuing to make work like this shields the workers from conscription for slave labor in Germany. The stamp designers, the stockmen, the inkers, the suppliers of ink, paper, and glue, the auditors all become essential workers in the Vichy administration. With this make-work perhaps some Frenchmen were protected from the dreaded Service de Travail Obligatoire.

Christopher Koch, ‘Highways to a War’ (1995)

The novel is a study of war photographers in South East Asia in the 1970s. The three principals are Jimmie Feng, Dmitri Volko, and Mike Langford; the last is the protagonist. Mike is from Tasmania and there is where I got this copy in 2014.

The descriptions of life and war in South East Asia are etched, and at times lyrical, the heat of the day, the bird song before sunup, the sapping humidity, the blinding sun, the people rooted to the land, the cool of the night,contrasted to the blare of American Saigon, the wumps of helicopters, the paralysing fear and chaos of a firefight, the confusion of battle, the mistrust of those people rooted to the land. It is all there in a kaleidoscope of sounds and colours. Much of the book can be read for a vicarious ride into the world of these war-lovers, as per the John Hersey novel.

The first experience of combat is terrifying. Enduring a B-52 bombing is unendurable. Volkov’s drunken lament is moving. The political theory seminar, complete with references to Hegel, in the jungle is compelling.

Mike is a Christ figure trying to save just about everyone and finding that he is all too human, too frail to do that. Indeed his unremitting inarticulate goodness wore down this reader. Even more tedious was his universal sex appeal; it read like an adolescent boy’s wet dream. Still worse was the recognition of his gift of grace in the early pages. The world does not work like that.

This reader was also worn down by 511 pages many of which were repetitious, first Vietnam and then Cambodia, each the same story told twice. Koch may have had to write it to exorcise his demons but I did not need to read it, and the second telling is lesser for my want of attention. Yes, I turned the pages ever faster.

Christopher Koch

Christopher Koch

Niggles, there were a few, I do not know what a ‘Tasmanian bluey’ is and neither did the Tasmanians I asked. I have never seen it spelled ‘tzarist’ before and neither has the spell checker. The many references, including some in the Launceston setting at the start of the novel, to the Australian Broadcasting Service in the 1970s made me wonder where the ABC was. By the way, we never do get back to Launceston despite the elaborate setup. I also stopped short at a reference to blue eyes in old photograph of a great grandfather. Do the arithmetic and that great grandfather’s photograph must have been in black-and-white.

I chose this book because I have read other Koch novels and trusted him on two counts, to have a story to tell and to tell it well. He met both those criteria despite my niggles and plaints.

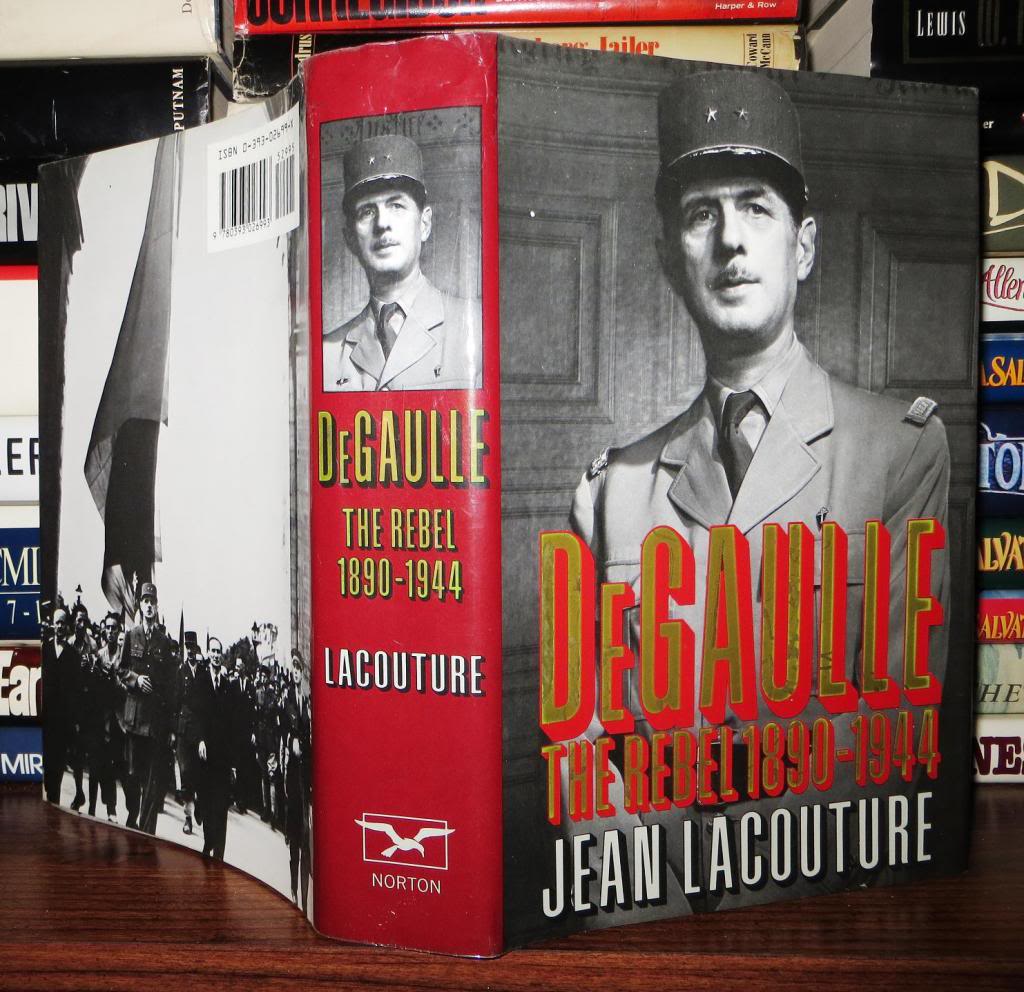

Jean Lacouture, ‘DeGaulle, The Rebel 1890-1944’ (1984)

When people hear that I am reading about Le Grand Charles most have a dismissive reaction as if to say ‘That fool!’ or worse. I get no such reaction to reading about Adolf Hitler or Erwin Rommel.

Does the memory of his veto of the United Kingdom’s bid to join the fledgling European Union still rankle? Does his icy reception of President Kennedy in Paris still itch? Does his determination to make France independent by (1) withdrawing from a NATO commanded by Americans and (2) developing nuclear weapons make him a villain?

That seems to be the superficial reaction. I say ‘superficial’ because I doubt any of these reactors know much of French history or his biography. This book offers a lot of both. As a foretaste of what follows, here are a few reasons by de Gaulle had no faith in the Anglos.

1.The British tried repeatedly to oust Free France from Syria and Lebanon when the Vichy Administration there collapsed.

2.The British colluded with the Americans for two years to displace de Gaulle with another, more pliable figure head. As to pliable see (5) and (6) below.

3.Whenever de Gaulle’s insistence that France was an Ally became too annoying the British would literally turn off his telephones, deny his vehicles petrol coupons, and end take-off and landing rights for the aircraft he used for transport in England and North Africa.

4.The Roosevelt Administration continued diplomatic relations with Vichy regime well into 1944, while that regime was busy deporting Jews to Germany.

5.Free France was excluded from all the planning of D-Day and the invasion of France in June 1944. ALL.

6.The American plan was to occupy France as though a belligerent and install military governors.

The list could go on but that is enough to indicate the sore points. To see some of the context read on.

When he decided to be a soldier, Charles de Gaulle grew up. His earlier dalliances with poetry and the life of letters fell away. His adolescent indolence and insouciance stopped from one day to the next. His indifferent school work suddenly became excellent. He is another example of Prince Hal or Achilles, a man born to the sword. Once committed to the Army, De Gaulle never looked back. He entered St. Cyr by examination and worked his way up from 150 in a class of 200 to 12. No one doubted that in another term he would be first. When he graduated he chose the infantry, unlike his peers who preferred engineering, artillery, or cavalry, each more glamourous than les poilus.

At 24 World War I started and de Gaulle was a captain at the front, shot in his first engagement. When his unit was transferred to the defence of Joan of Arc’s birthplace, sacred Verdun, he rejoined it there and served under the command of General Phillipe Pétain who praised young captain de Gaulle in dispatches. De Gaulle was bayoneted and captured, spending nearly three years as a POW in Germany. He had studied German since high school and he studied it again to aid his numerous, unsuccessful escape attempts.

In the long months of captivity he studied Germany and Germans in every way he could. He read the newspapers, spoke to and listened to the guards and the civilians who worked around the jail. He drew two conclusions from this study: (1) a civilian government mobilizes a country better than a military government because it is responsive to citizens and (2) Germans are resilient despite bad government.

For the moment stress the first, the primacy of civilian government. There is no doubt that de Gaulle, despite everything said about him by his many enemies, was a child of the French Republic and viewed it as the best form of government. He was never tempted by dictatorship of any kind under any name.

Wherever he went Charles de Gaulle had a mind of his own which he spoke. This characteristic slowed his progress up the army hierarchy but it also won him the support of Marechel Phillipe Pétain, such is the irony of history. Though he and Pétain were never close, Pétain made use of de Gaulle’s talents and protected him from some of the enemies de Gaulle made all too easily.

Prior to World War I the major debate in the French army was between the advocates of fortifications and those of firepower. Pétain took the side of fortifications and he found vindication in the killing fields of World War I. Firepower was so great it could not be overcome. Sheltering on the defensive in forts was the only solution. Out of this seed grew the Maginot Line.

De Gaulle drew a different conclusion, though he agreed that firepower was irresistible, his conclusion was maneuver, mobility, and movement. Hence his interest, even while a POW, in tanks.

After World War I the debate become more abstract. The received opinion in France was that war had to be managed through a series of doctrines that computed firepower, ratios, bullets per man,feet of cement walls, angles of fire, lines of wire, kilograms of steel in fortifications, ever more technical, mathematical, and abstract. A Cartesianism gone mad that René Descartes would not have recognised. Everything must be planned and calculated far in advance, then the army ants move like clockwork according to the plan, directed from afar by telephone and radio, observed from above by airplanes.

De Gaulle rejected this approach period, and said so in the first opportunity when he, then a junior officer, addressed a seminar of very senior officers who had all supped on doctrine. Rather he argued that it was circumstance, the unanticipated opportunities, that led to victory. These are first and best perceived at the lowest level of command, the sergeant, not in a manual of doctrine or at the end of a telephone wire in Paris. He advocated an army based on sergeants! At this rank the French Army should recruit educated and stable men, retain them with good pay and conditions, and train them (map reading, codes, signals) so that they could recognize opportunities and take initiatives. Hardly what the demigods of the École de Guerre saw as their mission. That Moltke the Elder, Napoléon, and Caesar could be quoted in support of this thesis helped not at all. Off de Gaulle went to distant posts in Poland, Germany, and Syria. Had World War II not intervened he would no doubt have been assigned to the French Antarctic Territory.

To make matter worse, de Gaulle wrote and published one book after another, each contrary to doctrine. By the way in this writing he earned a reputation as a stylist of the first order. To read ‘Le fil de l’épée’ (1927) is to see why. It is spare, terse, laconic, and elegant. It emphasised the human element in combat not the technical; it stressed the concrete not the abstract. It argued that the soldier wins the battle at the edge of a sword, not the general at the end of a telephone line. The general trains and motivates the soldier, and directs operations in broad.

Not only was de Gaulle a democrat of the French Republic, he was never anti-Semitic, not even in the casual way that was common in those days. There are many examples of this kind of anti-semitism that mar Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels of this time. Some of de Gaulle’s mentors in the army were Jews, and he always remembered them. Moreover, Léon Blum from his prison cell in Vichy declared de Gaulle to be the leader of France.

Then the war came, and de Gaulle was plucked from a desk and assigned to a field command of light tanks. Within days of arriving, he launched a reconnaissance in force and engaged the Germans with some success and took several hundred supermen prisoners. This is one of the few initiatives shown by any French officer during the Phony War (September 1939-May 1940). His superiors chided him for riling the Germans and relieved him of command! Gallic logic.

Then in May, German General Heinz Guderian struck with Erwin Rommel in the lead, proving that the Ardenne Forest was not impassable, which had been the assumption of the French General Staff, proving that massed tanks can destroy an enemy contrary to the doctrine of static defence.

De Gaulle, promoted to brigadier general, was assigned to command a makeshift brigade of French tanks. With this scratch force he launched the only French counter-offensive of the war to cut Guederian’s communication slowing the German advance. Like Churchill and Hitler, de Gaulle had been under fire in World War I, and, unlike them, he had also been under fire in World War II, several times at the edge of the sword.

By this time the chain of command was disintegrating. Premier Paul Reynaud asked him to join the government to balance the defeatist that surrounded him, e.g., Pétain, who had been advocating an armistice for days. Reynaud sent de Gaulle to London to motivate the English into making a still greater commitment to France.

Between 1932-1939 there were fourteen (14) minister of defence. Each busy undoing the work of his predecessor as the government lurched from one crisis to another.

That old chestnut that people unite against a common enemy is belied in this story.

Even as the Germans were flanking Paris in June 1940, Generals Maxim Weygand and Maurice Gameilin were undermining each other and writing letters to prove that the defeat had nothing to do with them. In one very embarrassing episode Weygand prowled the halls of the Ministry of War trying to get cabinet ministers and generals to sign a petition exonerating him of any responsibility. Comic opera, but for the gunfire.

Churchill was tempted to do more in France but he was surrounded by officers who told him France was lost and it was necessary to preserve British forces for the coming battle of Britain.

Then in a master stroke that has since faded from history, Churchill offered to unify France and Britain as a single nation, with a single government, and to defer to Reynaud as head of that government, if only the French would fight on in France or take the government into exile to London or Algiers. Reynaud was ready to accept the offer of union but his cabinet, by this time meeting in the Bordeaux town hall, was defeated, and rejected the offer in a few minutes. Better to make peace with the Germans than to enter into a covenant with perfidious Albion!

Like many others who emerge as leaders, the deeper the crisis became, the more disastrous the situation, the calmer, cooler de Gaulle became. At the last joint meeting of the Anglo-French War Council, Churchill described de Gaulle as imperturbable, relaxed, and yet alert and — most of all — with a plan….! The plan was a far-fetched (a redoubt across the Breton peninsula, but he was the only Frenchman at the table with positive action in mind, indeed, the only one to make eye contact with the English. The others stared down at the table top in silence. Beaten men, they were defeated. When Churchill passed de Gaulle leaving the room he paused and said to him ‘Vous êtes la France.’ Little did either of them know what was to come.

Though commissioned to ask what terms the Germans would offer, Prime Minister Pétain instead declared a unilateral ceasefire in his second day in office, and capitulated to the Germans with no effort to negotiate or permit the government to choose exile as the Dutch, Danes, and Norwegians had done in preceding weeks. Some say that Pétain’s actions were thus illegitimate.

In London two days after the capitulation de Gaulle went to the microphone in defiance of the obvious facts that France was lost; in defiance of the government of Pétain; in defiance of a great deal of public opinion in France that the war was over, and thank God for that! In defiance of the French community in London which wanted nothing so much as a low profile.

‘France has lost a battle; the war goes on!’

‘France has lost a battle; the war goes on!’

There is much more to tell but it is best read. Instead of going into those details, let us take a look at the man himself. He married Yvonne, he said, because she had the best mind. He read most of his manuscripts to her, when possible, and accepted her judgement on style. His daughter Ann was born mongoloid and thereafter much of the family life revolved around her. There was never any question that she, Ann, would be secreted away in an institution though that was the common practice at the time. To the extent possible Ann would have an ordinary life with her siblings. His sons all carried arms in the Free French military.

Anne de Gaulle, ‘Maintenant elle est comme les autres.’

Anne de Gaulle, ‘Maintenant elle est comme les autres.’

Second only to Yvonne was lifelong influence of his father and then his brothers. They were a close knit clan and stayed that way. The adverse publicity that Charles brought to the name of de Gaulle was worn as a badge of honour. By 1944 the Vichy Regime had rounded up all of his relatives and they were deported to German slave camps. That included his elder sister, cousins, nieces and nephews, and few of them survived the ordeal. Is it any wonder that later he refused any truck with the Vichy Regime, despite the insistence of President Franklin Roosevelt. Non!

De Gaulle, the rebel, has an impressive CV.

1.In 1912 a very junior lieutenant de Gaulle advocated mobility in a unit commanded by Pétain that singular proponent of fortifications.

2. In 1917 Captain de Gaulle lectured senior field officers on the stupidity of ‘attack at all costs’ against machine guns which many of them had ordered.

3.In 1924 Captain de Gaulle published articles in both popular and technical journals arguing that circumstance determines success, contrary to the French Army credo of doctrine. He is sent to Poland as an observer.

4.In 1927 he lectured future generals on the importance of sergeants in combat, not High Command.

5. In 1928 Captain de Gaulle refused to comply with General Pétain’s demands for intellectual flexibility. He is posted to Syria.

6.In 1934 Captain de Gaulle published a book opposing the doctrines of High Command predicting that the next war will be won by massed tanks supported by aircraft which will punch through any defensive (Maginot) line.

7.In 1937 he published yet another book disputing the doctrines of high command against the express wishes of Pétain.

8.In 1940 de Gaulle mailed a tract denouncing the conduct of the war to 80 superior officers.

9.Against orders to do nothing, Colonel De Gaulle launched his tank regiment on a reconnaissance in force against the German, netting 500 prisoners, and proving that French tanks can best Panzers.

10. On his own initiative in 1940 General de Gaulle launched the only counter-attack the French Army offered, briefly cutting Guderian’s line of communication.

11. In1940 in London General de Gaulle re-directed a French shipload of military equipment diverted to England.

Philippe Pétain rescinded de Gaulle’s promotion to General, put him on the army’s inactive list, retired him from the army, stopped his army pension, declared him a traitor, withdrew his citizenship, and launched legal proceedings in abstentia against him in both compliant civil and military courts where he was sentenced to death. Lest that all seem comic opera it is sad to say that others likewise tried in astentia did fall into the hands of Vichy authorities and were executed. Italy, Portugal, Spain, and even in one case the United States surrendered individuals to Vichy arrests. Likewise those who fled to French colonies (from Algeria to Madagascar) were sometimes arrested and returned to Vichy where they were murdered. Shades of ‘Casablanca.’

As to anti-semitism, consider this. When De Gaulle secured control over Algeria and Tunisia in 1943, his critics, including that completely cock-eyed American ambassador Robert Murphy, said de Gaulle was stirring up the Arabs. What de Gaulle did to stir up Arabs was stop the deportation of Jews from Algeria to Germany, which the Vichy governor François Darlan had been doing assiduously while Murphy looked on.

De Gaulle was long suspect to both British and American authorities because the Free French he assembled included communists, socialists, nationalists, royalists, reactionaries, regionalists, fierce individualists, and every other political stripe. All he asked was that they fight the common enemy under the tricolor.

From that radio broadcast on 18 June to July 1944, de Gaulle went from the most junior general in the French army to the head of the provisional government of France. It was a long, hard road with many setbacks, a lot of mistakes, and much opposition, but in its course he brought France back to life. In November 1944 there were 350,000 Free French troops in Western Europe. General Alphonse Juin’s First French Army played a decisive role in Italy. General Phillipe LeClerc’s army liberated the south of France. Earlier in Africa Generals Jean Lattre de Tassigny and Pierre Koenig held the flank for the British at El Alamein. All of this started with that one man with an idea at a microphone. Though it was a capital offence to listen to his broadcasts in Occupied and Vichy France, Vichy authorities estimated his audience at three million (3,000,000)! What did John Stuart Mill say about one man with an idea? In this case de Gaulle’s idea was France.

By the way, I note once again with interest that de Gaulle never promoted himself, unlike all those tyrants that his enemies likened him to. He retained his rank as a brigadier general. Every other general outranked him, including those who served at his command in the Fighting Free French. Even from the first days in London at least two full generals and an admiral of the fleet put themselves at his command. They recognised leadership beyond rank.

Despite the efforts of Ambassador Murphy, acting for Roosevelt, to undermine and displace de Gaulle he continued and in a coup de main in 1943 the Resistance in its many forms joined together briefly to recognise General de Gaulle as the voice of fighting France. The many European governments-in-exile in England recognised de Gaulle’s committee as the sovereign of France, too, though it took the Anglo-Saxons powers much longer to do that thus sewing the seeds for future resentments.

Even in early 1944 Ambassador Murphy was still plotting some kind of transfer of allegiance of the remnant of Vichy to the Allies bypassing de Gaulle completely and recognising Pétain as the sovereign! The same Pétain whose primer minister Pierre Laval was an ardent Nazi. A plot that de Gaulle scuttled but which he never forgot. Put the shoe on the other foot: What if de Gaulle had endorsed Thomas Dewey against FDR in 1944?

Finally, D-Day and the invasion of France was planned without any participation from the Free French, and the plan was to occupy France and install military governors. Believe it or not. This was an insult de Gaulle never forgot. This is a story in itself. Within days of 6 June, de Gaulle with a small entourage marched onto a British ship, unauthorised, bound for the Normandy beaches, went ashore, and installed the first Free French prefects in the smoking ruins of town halls. As he strode down roads and streets that had just been fought over, he was mobbed by the locals. They had no doubt who their leader was.

As to the book itself, the judgements are few but very finely drawn. The prose is elegant, though there are too many distracting translator’s notes asterisked into the text * and ** and *** and, on one page, ****. Readers should note that the French grammar is preserved in a literal translation that often throws an English reader used to word-order grammar. There are also many cryptic references to figures and events in French history that escaped me.

Lacouture is a journalist of the old school, one who values truth, seeks several sources for confirmation, interviewed everyone he could and who prefers understanding to glib judgements, and leaves conclusions to the reader, altogether a now vanished breed. He would never get a job at the ABC.

Jean Lacourture

Jean Lacourture

I read the two volumes of this biography in the 1990s when Kate gave it to me, and this is a second reading. I will read the second volume soon.

Garry Wills, ‘Certain Trumpets: The Call of Leaders’ (1994)

All the reading about presidents brought me to Garry Wills’s book on leadership. It is so much more insightful, intelligible, digestible, and accessible than James McGregor Burns’s ‘Leadership’ (1979), often cited as the book that created leadership studies. Burns tries to bring everything–and I mean everything–under the heading of leadership, the result is like those banquets when all the courses from the soup to the dessert appear at once. Too much.

Wills’s book presents sixteen chapters profiling a leader matched with an anti-leader. His approach is informed by Max Weber, Thorstein Veblen, and Burns, but not with the straight-jacket such frameworks often produce. There is an opening discussion that separates leadership from management and from influence and a concluding chapter that emphasis context accompanied by thirty pages of notes. Though it reflects a great deal of study and research the book reads easily; I read it in one sitting.

Some of the usual leaders are rehearsed like Franklin Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln along with Eleanor Roosevelt, Harriet Tubman, Mary Baker Eddy, Martha Graham, selecting leaders from sports, business, diplomacy, military, and more. The point is that political leadership differs from sports leadership differs from business leadership, and so on.

There is not a single thing Leadership that fits all cases. It is a simple point but it is hotly contested in both the popular leadership books and the academic literature on leadership. By the same token, to set leadership apart from management and influence is contested. Though both separations seem dead obvious to me but when I said so at conferences I walked into a firefight.

I learned more about Napoleon from Wills’s twenty page chapter than from the three biographies I have read, the shortest having 550 pages. They all had much more detail but less meaning than this chapter. The anti-leader set against Napoleon is George McClellan. Say no more. Though it is tempting to nominate Braxton Bragg who combined McClellan’s incompetence with spite.

Wills’s passing remarks contrasting Nancy Reagan to Eleanor Roosevelt won my applause. Now I know why I found the former so distasteful.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt

Cesare Borgia is his example of an opportunistic leader and Wills’s main source on Borgia is one Niccolò Machiavelli. This is one chapter I read closely; yes, there were some I flipped through, admiring Wills’s breadth but not engaging with the substance. Borgia recognized that conditions change and success means both responding to those changes, and where possible anticipating them. Failure lies in ignoring or resisting these externalities.

Garry Wills in 1994.

For every leader he included there are others omitted. Winston Churchill and Huey Long are absent. For every leader included there are qualifications. With age Napoleon lost the audacity that made him. For every leader included, there were mistakes. Franklin Roosevelt picked fights he could never win early in his career but he learned not to do that.

‘The Lost World of James Smithson’ (2007) by Heather Ewing

I have visited Smithsonian museums many times in Washington D.C. At last count there were nineteen (19) of them on the Mall. Vast and varied!

I vaguely knew that James Smithson (1764-1829) started it all with a whopping great cash gift in the 19th Century, and that Smithson was English and never set foot in the United States. That satisfied my need to know (-it-all) for years.

My interest was pricked a few month ago in reading a biography of John Quincy Adams, sixth President of the United States. Uniquely, after he left the presidency, defeated in a bid for re-election, he served in the House of Representatives for nearly twenty years, dying at his desk. In Congress he was instrumental in securing the Smithson gift and putting it to work as Smithson intended. (There were others who hoped to siphon the money off for their purposes; these others included the sitting president, Martin van Buren.) Quincy Adams navigated through these sharks and shoals, arriving at the first museum, the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, that is the red brick building often referred to as the Smithsonian Castle these days, from the turrets of which Abraham Lincoln observed the Confederate Army at Harper’s Ferry in 1862.

Taken as read, I thought no more of it, until I happened to mention Quincy Adams’s role to a friend, who did not know that the Smithsonian was started with a private bequest or that the donor was English. I then realized how little of the story I knew because I could not shed any light on how or why the gift was made.

Clearly it was time to top-up my know-it-all tank and I sought out and read a biography of James Smithson. What did I find?

He was born to an English mother in France, where she had gone, as have many others, to have her illegitimate baby. The father, most likely, was the Duke of Northumerland, a man who owned about one percent of England. His mother was volatile and threw her own considerable wealth into one endless, pointless, and unproductive lawsuit after another trying to get yet money out of others. James grew up speaking French with other children and English with his mother. When she returned to England with him, he had to be naturalized. The Duke never recognized either his mother or him in any way.

Naturalization took an act of parliament, though routine, it was also conditional, namely that James, like all the others, was prohibited from holding public office, either elected or appointed, and could not receive any benefit from the crown, e.g., a royal pension. Later in his life he bristled as these restrictions, as well as the illegitimacy which prohibited him from taking his rightful place in society, as he saw it. He was twice estranged, once socially and once politically from Mother England.

His mother indulged him and used her contacts to get him into Oxford, at one of the lesser colleges, Pembroke, which contrary to the other more prestigious colleges, emphasized learning — rather than drinking and gambling — and even more unusual it emphasized science, and most unusual of all that dirty and stinking science where even a gentleman got his hands dirty — chemistry. It was a time when many advances were being made in chemistry outside the two historic universities and the Master of Pembroke College, striving to elevate the reputation of the college, went into chemistry with enthusiasm. Smithson loved it. He published many papers, and was elected to the Royal Society at twenty-two, the youngest ever at that time.

He inherited modest means from his mother, and invested it in canals and railroads, and made a lot of money out of each, which he reinvested, accumulating far more dosh than he could spent of display cabinets for his mineral collection, or blowpipes for his chemistry experiments, or on his travels.

Like other young gentlemen of his class and era, he made a Grand Tour through Europe; in fact he made three such Grand Tours. Whereas others frequented galleries, salons, and cathedrals, Smithson sought out chemists, chemistry laboratories, minerals, mines, and miners. He took meticulous notes, collected many specimens (rocks and dirt to the inn-keepers who often refused his baggage entry), measured anything that could be measured, and tried to measure some that could not be measured. Amateur scientist, yes, but deadly serious and completely focussed. He had several unwanted adventures on these Tours because Europe was rent by the Napoleonic Wars, e.g., he spent a year in a cold, stinking prison in Hamburg as a British alien at a time when all of Germany was occupied by Napoleon’s army, which saw a spy in those copious notes Smithson took of the geography and geology. In his travels around Europe he must have crossed paths with John Quincy Adams, on his many diplomatic missions, but they did not meet. Did he ever came across Ethan Gage?

Many of his English friends who had supported the French Revolution in the early days, were suspect in Great Britain as Jacobins. A few went into voluntary exile, including several to the United States, and they wrote to tell Smithson of the premium given to science in the United States. He also met Americans on the Grand Tour and they also told him that science was uninhibited and valued in the United States. He noticed when the incumbent President John Adams lost to Thomas Jefferson one was the President of the American Philosophical Society and the other President of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The two leading political figures of the decade were intellectuals! Did George W. Bush ever read a book, after ‘The Little Prince,’ I wonder? Bill Clinton stopped reading with ‘Little Red Riding Hood.’ Mitt Romney and books…does not compute. Barry O’Bama only reads himself.

In addition Smithson saw the vast private museum of Lumley Keate, a distant relation, broken up and auctioned, when all lamented that such a carefully acquired and artfully curated collection was sold piece-by-piece as curios, rather than preserved as a whole. In an England impoverished by the endless wars with Napoleon, there was no public means to capture this patrimony for the country. England along with Europe was consumed by wars from Portugal to Russia and the Baltic Sea to Sicily, leaving little time, space, or finance for science.

He continued to travel in Europe, despite the upheavals and convulsions. His health had never been good, and after that year in prison it got worse. Whole years are missing from the tale because the intrepid author could find no record of his activities, and surmises he was laid up somewhere recovering his strength. In 1829 he died in Genoa, Italy where he had gone see a collection of mineral specimens. He was buried there and in due course his will was probated in London. He had made the will some years earlier; he wrote it himself without consulting a lawyer; this is always a recipe for trouble. In it he left the income of his worldly goods to a nephew during the nephew’s lifetime, his only living relative, and the goods themselves to be divided equally among the nephew’s children, legitimate and illegitimate, when the nephew died, and in a secondary clause, ‘to the United States of America to found at Washington under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.‘ A quaint second clause it seemed, until the nephew drank and whored himself to death in two years, dying without issue. Accordingly the secondary clause applied. [Aside, reader of Charles Dickens’s ‘Bleak House’ know what is coming next: The Feast of the Lawyers.]

The British Government, skint from all those Napoleonic Wars, moved to seize the fortune for the Crown. Somerset House informed the American minister in London, who passed the word to the President (Andrew Jackson). A plenipotentiary was dispatched to London to secure the money for the United States. He did superb job, no doubt paying bribes, to keep the matter out of the Chancery Courts. It was Richard Rush, a wily Pennsylvanian, who had been United States Attorney General for President James Madison and Secretary of the Treasury for President John Quincy Adams, and previously ambassador to the Court of St. James. He wrestled the money from the British Bulldog in only two years. Various distant relatives of Smithson, retainers, friends, some of many scientific associations Smithson frequented, all tried to contest the will, and Rush parried each.

That was only the beginning of a story that would take another book to tell in detail. The short version is that no one in Washington wanted the gold. (Rush brought it to Washington in twenty-one chests, each filled with gold bars!) Southerners thought it would enrich the federal government to dominate the states with their precious states right (to slavery) and Northerners thought it was a devious British plan to take over the country.

How big? About 100 million pounds today! That is about $US166 million or $A179 million today.

A satellite image of the eastern half of the National Mall with 10 Smithsonian museums located on it.

This is what the money bought. The Castle is 14 above. This is only half the Mall, the others are on the west end. (1, 7, and 8 are not Smithsonians.)

In time the Smithsonian Institution on the Mall emerged, though it took many hands, like Quincy Adams, Alexander Graham Bell (yes, Don Ameche invented the telephone), Joel Poinsett (the flower man), and others to overcome, first, the objections, and then to stave off the swarm of special interests who wanted all, most, or some of the money siphoned off into hundreds of pet peeves, from butterflies in Maine, to public lectures in every town on fingernail clipping, and so on. It took years. Work began on the red castle in 1855 about twenty years after Smithson’s death. Even then claims from relations and retainers continued to arrive at the White House. I expect they still arrive today, addressed to the Smithsonian!

Where did the money come from? Why did he do it? The first is the easier question to answer. He invested in canals and railroads, and was one of the first to do either and one of the few to do both, and they each paid off and continued to do so all of his life. He also invested in inventors, some of whom paid him back twenty times over.

Why did he do it? Let’s break that down into some smaller, more focussed points. What we have here is multiple causation.

Let us be clear he left his money to his only living relative, that twenty-five year old nephew. Only when fate intervened did that secondary clause come into play. Perhaps it was a amusement for him to write in that afterthought.

He had long been estranged from England by the reactions to his illegitimate and foreign birth. He was completely divorced from the French by that year in the slammer. More generally, he saw Europe bent on destroying itself. Wherever he went there was war, France, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Austria ….

He had seem examples of philanthropies in England and France, though few aimed at scientific knowledge. Rather he had seem great scientific collections sold as paperweights, while to find specimens he had had to travel the length and breadth of Europe.

Did he want to immortalize himself as a man of science in a way that his own scientific labors did not achieve? He was a very able and dedicated chemist but he made no breakthroughs to put him in the pantheon, and he knew it. If so, Europe was not the place.

From the United States he had heard many good stories about the value of science there and that democracy did not hold a man of talent back because of his illegitimate or foreign birth. (He had a total loathing for sea voyages and never thought to go there. Even to sail from England to France was something he avoided, in one case, for four years, so much did he fear the ocean.)

The book is a sterling example of thorough research and the dexterous handling of uncertainty, and speculation. Little is known of Smithson’s life, partly because trunks with his private papers burned in a fire, much has to be inferred. The author tracks him rather like astronomers identify celestial bodies by the distortions they cause passing in front of star fields. She has combed bank records, passport files, police reports, and the correspondence of his contemporaries for mentions of Smithson and draws conclusions from them. The author handles these inferences well, they are qualified but integrated. There are many ‘possibilies,’ ‘surelys,’ ‘probablies,’ ‘maybes,’ and so on. None of this is easy, not even that name Smithson for it was not his birth name. For details, read the book.

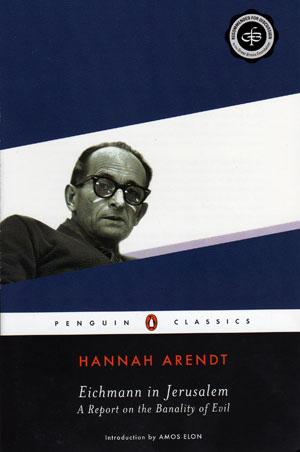

Hannah Arendt, “Eichmann in Jerusalem” (1963)

I re-read Hanah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” inspired to do so by the film “Hannah Arendt.” By the way, the subtitle “The Banality of Evil” is implicit in the book and stated only on the last page by way of conclusion on page 252. At the end of this review staunch readers will find a note about Howard W. Campbell at the end. (Don’t know about Campbell? Then read on to find out.)

Despite the furore at the time, portrayed in the film, Arendt did not:

1. In any sense exonerate Eichmann,

2. Condemn Jews in any way,

4. Blame Jews for their own destruction,

5. Assail the court proceedings,

6. Oppose the death sentence,

7. Question the legitimacy of the trial, and

8. Assert that Eichmann was a Zionist.

Though each of these lies was said at the time dutifully repeated by those that do not think but react.

Once one of these falsehoods was said, it was repeated by other journalists too lazy or irresponsible to check the facts, long before Rupert Murdoch could be blamed. Needless to say none of the journalists who recycled these falsehoods ever apologised.

Nor was such intellectual laziness limited to journalists. Over the years I have heard them from academics who should know better than believe everything they read, something they quickly condemn in students while doing it themselves.

First things first, the role of Jews in their own destruction is there, reported as fact throughout the book, the local organization of the Jewish Council. Where a Jewish Council did not exit the Nazis tried to set one up. Some Jews who cooperated with the Nazis in these councils were later themselves tried for crimes in the Successor Trials that followed The Nuremberg Trials but not specifically for crimes against Jews. She does not sensationalise this Jewish cooperation, and acknowledges that in its early stages in Western Europe it may well have seemed the best thing to do.

She also points out that others cooperated in their own destruction at times when whole peoples were moved, deported, and then murdered. Likewise she is very clear that resistance was impossible.

In all these references to Jewish cooperation amount to, say, fifteen pages of the 300 in the book. Perhaps a little more.

Second, it is forcefully argued that Eichmann in Jerusalem was demonised in order to allow the trial to tell the whole story of Jewish persecution and destruction. That is why the prosecution introduced volumes of material that had nothing to do with Eichmann. He was a cog, albeit a vital one, but nonetheless a cog, not a director, decision-maker, influencer of others. He was a cog who could have been easily replaced. But the trial was not about him, and is that not what trials are supposed to be about, the defendent. In exile on Argentina, Eichmann did boast of his part in the Final Solution, true, but perhaps he did this to ingratiate himself with the exiled Nazis he found there as much as anything else. Men do brag and exaggerate, now don’t they?

Third, all the nations occupied by the Nazis had Successor Trials shortly after the Nuremberg Trials. None of these trials presented indictments about murdering Jews. Having no state, Jews did not. Israel as the Jewish state had as much right to hold such trials as any other state, she concludes.

Eichmann’s self-defense was that the emigration, evacuation, and destruction of Jews were acts of the German state which were above the law and normal morality. Though he did often refer to orders, “ein befehl ist ein befehl,” and even mentioned Immanual Kant. His six-day interrogation, his testimony in the trial, his many written submissions are muddled, inconsistent, repetitive. He was working only from memory in Jerusalem and he was not a bright man to begin with. No Albert Speer he.

While rejecting resistance as a possibility she also reviews and dismisses the pop psychology explanations of the Jewish cooperation in their own destruction as some kind of death wish. One reviewer of the book said the same of her. That she had written a negative book about Jews because she hated herself as a Jew. There is no limit to imbecility.

All of Eichmann’s social, intellectual, bureaucratic superiors knew and accepted the destruction of Jews. Who was this functionary, one-time salesman, to judge compared to them? Remember not all the professional officials were Nazi thugs. At The Wannsee Conference where Eichmann did the coffee, Count Ernst von Weisacker represented the Foreign Office. Eichmann was thrilled to be in such distinguished company at the time.

There seems also to have been a big difference between the approach to the Final Solution in Eastern Europe compared to Western Europe. In the east there was no local government, e.g., Poland, a puppet government, e.g., Croatia, or a Fascist ally like Hungary. Sometimes for a while Western European Jews had some protection afforded by their own governments, although Jewish refugees say in France were surrendered quickly. But by 1944 even this protection was not enough. Italy seems overall to be the best place for any Jew, including refugees who could disappear into the crowds, hills, forests. Bulgaria is another country where the unwillingness of locals to cooperate stymied the Nazi killing machine. Belgium is another exception because there many, many Jewish refugees and almost no Jewish organization, the Nazis had no place to start. But almost from the start German, Polish, and Russian Jews were murdered on an industrial scale. By 1944 nothing stopped the Death Machine.

Eichmann on trial

Her argument is that the crimes were unprecedented and so the justice done them had to be likewise unprecedented. [Everyone knew they were crimes which is why all the euphemisms were used. She does not consider this point, though she notes how seldom there was an explicit reference to extermination, killing, murder, etc.]. Law serves justice. Law should not thwart justice. No graduate of a law school would ever say that!

She has many criticisms of the lackadaisical and incompetent defense attorney who seemed to neither know nor care much about the events, Eichmann, or the trial. She is also very scathing about the melodramatic, wandering prosecutor who never seemed to focus on the accused.

In the end we have great evil partly done by this pathetic, hardworking, if stupid and unimaginative individual. He was shallow, unread, incapable of learning from his experiences, unreflective and untroubled by what he was doing. What he did care about was his career advancement and he spent lot of time, rather incompetently, trying to secure promotion. He never read a book, certainly not a novel, a poem, or a play, and probably nothing more taxing than a few pages in coffee table books, if that. He flunked out of both high school and vocational training. He repeated clichés and stock phases he heard without grasping their meaning or their trite nature. He is no Faust aware that he had sold his soul to the devil for a few magic tricks.

The Nazis were able to destroy as many Jews as they did, in part, because Jewish communities were so well organized and disciplined. When the Jewish Council in Poznan told a list of families to assemble at the train station for resettlement, they did. This order made the fiction easier to bear, as Eichmann dimly realized, but it made the killing easier. If the Jewish Council had told the truth, it is not resettlement but murder, or refused to cooperate the result would have been terrible, but perhaps fewer would have died. Perhaps. It is a question Arendt asks, and she speculates that fewer would have died though with foreknowledge and dread. Does the doctor tell the terminal patient the truth of allow the patient to die in hope?

Safe to say we have all met people like this Eichmann, but fortunately none of them held the power of life and death over us. They even exist in universities, a PhD is no guarantee of thinking. [Jackson pauses to recall several exemplars.] We all react to stimuli but seldom do any of us think. Some people never do. Ameboa react to stimuli, too.

Not everyone who does great evil is a fearsome demon. Readers may recall that in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel “The Brothers Karamazov” the devil that visits Ivan is a dirty, smelly, stupid, and vulgar lout. He is no Mephistopheles, but rather Anyman. Simone de Beauvoir said something similar about Pierre Laval, evil but insignificant. Of course, years after their crimes, defeated,captured, reduced to prisoners, not even vicious killers seem very threatening.

The book exudes urgency and importance. The prose is hard and clean, no embellishments, no learned references, very few citations of other studies though some. It is easy to imagine the author pounding it out on a typewriter to meet a deadline, not an editorial one, but In this case a moral one, namely get it all and get it right. There will never be another chance. Of course, she made mistakes in proper names, sometimes, in dates by a week or a month, and there are overstatements a few times. These errors have been pounced on by reviewers for years, who themselves evidently have never made a mistake, to discredit the entire book.

I noted that the Dutch journalist Harry Mulisch is cited a few times. I found his novel “The Assault” a compelling book, ditto the film based on it. Infinitely sad and yet somehow satisfying it was when the message is at last delivered. That would have been a better name for the novel, “The Message.”