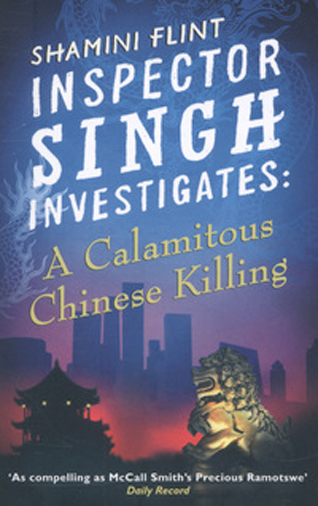

Recommeded for Crime-travellers.

Inspector Singh Investigates is a series of six novels following the adventures of an overweight, lazy, down trodden Sikh, depressed Singapore police officer.

He is very unSingapore with his curry stained neck ties, his grubby white tennis shoes, slovenly appearance, not to mentioned the five yards of sweat-stained turban he sports. In fact, he is so unSinagporean that in nearly every novel his superiors (and they include all ethnic Chinese in Singapore, he thinks) send him as far away as possible. He has been sent to Kuala Lumpur, Bali, Cambodia, New Dehli, and now Beijing.

His assets are that he does not scare easily (thanks to the training of his wife and her many, many relatives) and can always find a supply of beer.

While Singh never takes anything too seriously, these stories are darker than I usually like. The compensation is the exotic locales, and an appreciation for Asian English in these places.

In ‘A Calamitous Chinese Killing’ Singh, assigned at the request of the Vice-Counsel at the Singapore Embassy in Beijing, finds himself caught between the merciless Chinese security apparatus and equally merciless Chinese corruption. Along the way he grows to respect the steel in the Vice-Counsel, a woman by the way, and befriends a penniless, retired, honest Beijing detective who introduces him to Szechuan cooking which Singh finds an acceptable accompaniment to beer.

His bacon is saved when he manages to bring these two behemoths — the forces of security and the forces of corruption — into conflict. While they slug it out, justice of a kind is done. Though many innocents are killed and psychologically scared. As I said, dark.

Singh has company among Singapore sleuths in the person of Mr Wong and his associates written by Nury Vittachi. Wong is in the private sector.

He has his footwear in common with Hermes Diaktoros penned by Anne Zouroudi who wanders the by-ways of Greek islands.

Category: Book Review

Judge Woolsey’s decision on ‘Ulysses”

I still labour in the land of ‘Ulysses.’ I have listened to Melvyn Bragg’s ‘In Our Time’ episode on ‘Ulysses,’ again, and got some interesting points from it. But what I got most of all was the Solomonic wisdom of Judge John Woolsey’s opinion which is quoted in full below.

Bennet Cerf, when he published the book on the day of this judgement in 1933, included the opinion in every edition, making it the most widely distributed judicial opinion ever. In reading about the case I noticed how reluctant the District Attorney was to bring the action and how the Customs Service ignored the injunction for weeks and weeks. The DA and Customs both seemed to think they had more important things to do.

I could find very little about Judge John Woolsey on the interweb. He was from South Carolina. There is an entry on him in the online History of Federal Judiciary but I could make the link work. The only picture I could find came from the cover of the ‘James Joyce Quarterly.’

By the way, the District Attorney said he felt the book was a masterpiece of insight. The Customs officials said everyone brought it back from Europe and that it had caused no harm, so what was the fuss? The Appellate Court upheld Woolsey’s decision on the points law.

Banning ‘Ulysses’ – Judge Woolsey’s Decision

Opinion A. 110-59

December 6, 1933

[Edited out the technical matter.]

I have read ‘Ulysses’ once in its entirety and I have read those passages of which the Government particularly complains several times. In fact, for many weeks, my spare time has been devoted to the consideration of the decision which my duty would require me to make in this matter. ‘Ulysses’ is not an easy book to read or to understand. But there has been much written about it, and in order properly to approach the consideration of it it is advisable to read a number of other books which have now become its satellites. The study of ‘Ulysses’ is, therefore, a heavy task.

The reputation of ‘Ulysses’ in the literary world, however, warranted my taking such time as was necessary to enable me to satisfy myself as to the intent with which the book was written, for, of course, in any case where a book is claimed to be obscene it must first be determined, whether the intent with which it was written was what is called, according to the usual phrase, pornographic, — that is, written for the purpose of exploiting obscenity. If the conclusion is that the book is pornographic that is the end of the inquiry and forfeiture must follow.

But in ‘Ulysses,’ in spite of its unusual frankness, I do not detect anywhere the leer of the sensualist. I hold, therefore, that it is not pornographic.

In writing ‘Ulysses,’ Joyce sought to make a serious experiment in a new, if not wholly novel, literary genre. He takes persons of the lower middle class living in Dublin in 1904 and seeks not only to describe what they did on a certain day early in June of that year as they went about the City bent on their usual occupations, but also to tell what many of them thought about the while. Joyce has attempted — it seems to me, with astonishing success — to show how the screen of consciousness with its ever-shifting kaleidoscopic impressions carries, as it were on a plastic palimpsest, not only what is in the focus of each man’s observation of the actual things about him, but also in a penumbral zone residua of past impressions, some recent and some drawn up by association from the domain of the subconscious. He shows how each of these impressions affects the life and behavior of the character which he is describing.

What he seeks to get is not unlike the result of a double or, if that is possible, a multiple exposure on a cinema film which would give a clear foreground with a background visible but somewhat blurred and out of focus in varying degrees.

To convey by words an effect which obviously lends itself more appropriately to a graphic technique, accounts, it seems to me, for much of the obscurity which meets a reader of ‘Ulysses.’ And it also explains another aspect of the book, which I have further to consider, namely, Joyce’s sincerity and his honest effort to show exactly how the minds of his characters operate.

If Joyce did not attempt to be honest in developing the technique which he has adopted in ‘Ulysses’ the result would be psychologically misleading and thus unfaithful to his chosen technique. Such an attitude would be artistically inexcusable.

It is because Joyce has been loyal to his technique and has not funked its necessary implications, but has honestly attempted to tell fully what his characters think about, that he has been the subject of so many attacks and that his purpose has been so often misunderstood and misrepresented. For his attempt sincerely and honestly to realize his objective has required him incidentally to use certain words which are generally considered dirty words and has led at times to what many think is a too poignant pre-occupation with sex in the thoughts of his characters.

The words which are criticized as dirty are old Saxon words known to almost all men and, I venture, to many women, and are such words as would be naturally and habitually used, I believe by the types of folk whose life, physical and mental, Joyce is seeking to describe. In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of his characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season Spring.

Whether or not one enjoys such a technique as Joyce uses is a matter of taste on which disagreement or argument is futile, but to subject that technique to the standards of some other technique seems to me to be little short of absurd.

Accordingly, I hold that ‘Ulysses’ is a sincere and honest book and I think that the criticisms of it are entirely disposed of by its rationale.

Furthermore, ‘Ulysses’ is an amazing tour de force when one considers the success which has been in the main achieved with such a difficult objective as Joyce set for himself. As I have stated, ‘Ulysses’ is not an easy book to read. It is brilliant and dull, intelligible and obscure by turns. In many places it seems to me to be disgusting, but although it contains, as I have mentioned above, many words usually considered dirty, I have not found anything that I consider to be dirt for dirt’s sake. Each word of the book contributes like a bit of mosaic to the detail of the picture which Joyce is seeking to construct for his readers. If one does not wish to associate with such folk as Joyce describes, that is one’s own choice. In order to avoid indirect contact with them one may not wish to read Ulysses; that is quite understandable. But when such a real artist in words, as Joyce undoubtedly is, seeks to draw a true picture of the lower middle class in a European city, ought it to be impossible for the American public legally to see that picture?

To answer this question it is not sufficient merely to find, as I have found above, that Joyce did not write ‘Ulysses’ with what is commonly called pornographic intent, I must endeavor to apply a more objective standard to his book in order to determine its effect in the result, irrespective of the intent with which it was written.

The statute under which the libel is filed only denounces, in so far as we are here concerned, the importation into the United States from any foreign country of “any obscene book”. Section 305 of the Tariff Act of 1930, Title 19 United States Code, Section 1305. It does not marshal against books the spectrum of condemnatory adjectives found, commonly, in laws dealing with matters of this kind. I am, therefore, only required to determine whether Ulysses is obscene within the legal definition of that word. The meaning of the word “obscene” as legally defined by the Courts is: tending to stir the sex impulses or to lead to sexually impure and lustful thoughts.

Whether a particular book would tend to excite such impulses and thoughts must be tested by the Court’s opinion as to its effect on a person with average sex instincts — what the French would call l’homme moyen sensuel — who plays, in this branch of legal inquiry, the same role of hypothetical reagent as does the “reasonable man” in the law of torts and “the man learned in the art” on questions of invention in patent law.

The risk involved in the use of such a reagent arises from the inherent tendency of the trier of facts, however fair he may intend to be, to make his reagent too much subservient to his own idiosyncrasies. Here, I have attempted to avoid this, if possible, and to make my reagent herein more objective than he might otherwise be, by adopting the following course:

After I had made my decision in regard to the aspect of ‘Ulysses,’ now under consideration, I checked my impressions with two friends of mine who in my opinion answered to the above stated requirement for my reagent.

These literary assessors — as I might properly describe them — were called on separately, and neither knew that I was consulting the other. They are men whose opinion on literature and on life I value most highly. They had both read Ulysses, and, of course, were wholly unconnected with this cause.

Without letting either of my assessors know what my decision was, I gave to each of them the legal definition of obscene and asked each whether in his opinion Ulysses was obscene within that definition.

I was interested to find that they both agreed with my opinion: that reading ‘Ulysses’ in its entirety, as a book must be read on such a test as this, did not tend to excite sexual impulses or lustful thoughts but that its net effect on them was only that of a somewhat tragic and very powerful commentary on the inner lives of men and women.

It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned. Such a test as I have described, therefore, is the only proper test of obscenity in the case of a book like ‘Ulysses’ which is a sincere and serious attempt to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind.

I am quite aware that owing to some of its scenes ‘Ulysses’ is a rather strong draught to ask some sensitive, though normal, persons to take. But my considered opinion, after long reflection, is that whilst in many places the effect of ‘Ulysses’ on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac.

‘Ulysses’ may, therefore, be admitted into the United States.

JOHN M. WOOLSEY

United States District Judge

December 6, 1933

P.S.

By the way, to me Bennett Cerf was a panelist on ‘What’s My line?’ in the 1950s where he was the life of the party in a dry and droll way. He is second from the left.

James Joyce, ‘Ulysses’ (1921)

On Australia Day when I mentioned our forthcoming trip to Ireland, the host asked me I had ever read Joyce’s ‘Ulysses,’ I confessed, ‘No.’ Deftly I parried this admission of ignorance by suggesting that she read it for her book club! The riposte, taking me by surprise, was ‘Let’s you and I read it!’ Being a polite guest, I dumbly nodded. Gulp, what had I got myself into? But a deal is a deal. A few days later I went shopping. The local bookstore, yes we still have one nearby, had three editions of ‘Ulysses,’ being a very high brow concern, and I took the one with the largest print (and ergo the most pages, 933 — 933 — of them).

I have since seen several other editions, one with 300 pages of notes explaining the allusions, double entendres, and literary references. T. S. Eliot poems come with footnotes, too, explaining the idiosyncratic and obscure implications, that’s why I gave up him until ‘“Cats” came along! Joyce has yet had no such redemption.

As a rule I do not comment publicly on books I cannot be positive about but in recognition of the reputation of this book and the effort it took to read it, I make an exception.

Here I am nearly four weeks later at the end of a long and dutiful (a deal is a deal) march through those 933 pages of Joyceprose. [Calm down, editors, I am imitating Joyce’s style of run-on words, run-on sentences, missing objects after transitive verbs, et beaucoup plus [to imitate his gratuitous spicing of foreign terms]. These notes gather my thoughts.

This novel is usually described as modern, as in modernist, and his technique is equally, commonly described as stream of consciousness. I felt ready for both. I have a read a lot of modern novels, and the modernist ones among them were incomprehensible as I comprehended them. Alain Robbe-Grillet, Juan Louis Borges, Samuel Beckett, Luigi Pirandello, Robert Musil, Virginia Wolfe with their discontinuous story lines, the unreliable narrators, multiple points of view, unattributed dialgoue, the elaborate but meaninglessness red herrings, the inwardness, the self-referential, and meandering nothingness. (Starting to sound like a curriculum committee meeting.)

This novel is usually described as modern, as in modernist, and his technique is equally, commonly described as stream of consciousness. I felt ready for both. I have a read a lot of modern novels, and the modernist ones among them were incomprehensible as I comprehended them. Alain Robbe-Grillet, Juan Louis Borges, Samuel Beckett, Luigi Pirandello, Robert Musil, Virginia Wolfe with their discontinuous story lines, the unreliable narrators, multiple points of view, unattributed dialgoue, the elaborate but meaninglessness red herrings, the inwardness, the self-referential, and meandering nothingness. (Starting to sound like a curriculum committee meeting.)

I have also read plenty of streams of consciousness from William Faulkner (Benj in ‘The Sound and the Fury’), William Styron (Peyton in ‘Lie Down in Darkness’), and Thomas Wolfe (Eugene Gant in ‘Look Homeward, Angel). It is a technique that takes the reader into the mind, the world as seen by the mind, of a character as no other technique can do, and when it works, it is devastating, as it does in the three instances cited.

In ‘Ulysses’ in the early pages, I found the multiple voices and the passing-through conversations on the street interesting, as the parallel conversations in Robert Altman’s film ‘Nashville’ and the cryptic quality of some of the early remarks, incidents, observation were intriguing, think Gene Hackman in ‘The Conversation.’ In contrast to these films, however, in this modernist novel it is all technique and no payoff. Just showing off. Then after 900 pages Bloom goes to bed, disturbing his wife Molly’s lumber and her half-awake mostly asleep thoughts are the soliloquy that ends the novel in 60 pages without punctuation, apart from two randomly placed carriage returns.

As with an actor who speaks bad lines badly, we cannot hold the actor wholly responsible, after all a producer and a director allowed it to happen, and the writer who wrote the lines must be guilty. The same mitigation cannot be said for Joyce’s publisher.

Then there are the legions of admirers and enthusiasts like Frank Delany whose podcasts I listened to for a while, seventy episodes, yes 70, as he unpacked each and every reference in the text word-by-word, line-by-line, page-by-page, nearly all them minuscule, pointless, and adolescent. (Indeed, I thought Delany over-interpreted the text often making something out of nothing in the manner of a Phd dissertation, or those people who see human profiles in clouds.) In all, the book brought to mind Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s petty vindictiveness in his ‘Confessions,’ though Rousseau is even when spiteful in his dotage a wonderful stylist to be envied, unlike Joyce who seems to be determined to compensate for …. by being as deliberately naughty as possible, though the naughty in 1921 is trivial in 2014. It is in short an unremitting and totally self-indulgent memorandum of alienation from everyone and everything by someone privileged enough not to work on a farm or in a factory. An ordinary day with ordinary people, it is not, though that is often said of it. Ordinary people are much more purposeful and I rather doubt any of them would read this novel.

I did like one passage in particular, when one character muses on the differences between Romans and Jews in the ancient middle east. Jews come to a hill top, meditate and decide to build a majestic temple to the glory of god. Romans come to a like hill top … and decide to build … a toilet.

I am sure all the Irish have it in the genetic code to defend, if not truly to enjoy, James Joyce’s novels. So be it.

When we visit Dublin we will do a tour of some James Joyce and Ulysses sites to recoup a little on my investment.

I did get something out of the three weeks I spent with the book, putting aside all other reading to concentrate soley on it, and that is the right to strut on Bloom’s day next. (Joyceans will get it, and the rest will not.) Oh, I also got a strong desire not to read anymore James Joyce. ‘Finnigan’s Wake,’ which I am told is even more modernist than ‘Ulysess’ (which claims without ground an affinity with the eternal story of Homer)! Some people think that is a recommendation but I am not among their number. To me modernist means lack of punctuation, contempt for readers, and self-indulgence.

I did get something out of the three weeks I spent with the book, putting aside all other reading to concentrate soley on it, and that is the right to strut on Bloom’s day next. (Joyceans will get it, and the rest will not.) Oh, I also got a strong desire not to read anymore James Joyce. ‘Finnigan’s Wake,’ which I am told is even more modernist than ‘Ulysess’ (which claims without ground an affinity with the eternal story of Homer)! Some people think that is a recommendation but I am not among their number. To me modernist means lack of punctuation, contempt for readers, and self-indulgence.

I do, however, have plenty of other Irish reading in mind before we travel.

Grover Cleveland: A Biography of the President Whose Uncompromising Honesty and Integrity Failed America in a Time of Crisis (1968) by Rexford Tugwell.

After reading the condescending remarks about William Jennings Bryan’s lack of presidential intellect it was amusing to read this study of two-term president Cleveland who was Bryan’s exact contemporary. Bryan got by with the Bible for reading, Cleveland’s horizon did extend even that far. He never read a book and never opened an atlas. Never left the United States, and only made one trip around the country when president. For a politician he was nearly anti-social.

Paul Burns, The Brisbane Line Controversy (1998)

A testament to hot hardened air turning into fact. The bigger the lie, the more it is repeated, the more likely it is to be believed.

Continue reading “Paul Burns, The Brisbane Line Controversy (1998)”

Pel is at it again! Look out!

After reading a few rather taxing books I gave myself a treat by turning once again to Evariste Clovis Desire Pel. Amusing, implacable, exasperating, coughing, and determined as usual is Pel. Even Madame Pel calls him Pel.

The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson by Herbert Hoover (1958)

This is a book about a president by a former president. It is unique and must reading for presidentialistas. It is all the more distinctive since Wilson was a Democrat and Hoover a Republican.

Could it happen again? Would a Republican Bush write a tribute to a Democrat Kennedy? Or a Democrat Clinton to a Republican Reagan?

The ordeal is the war and the peace of the Great War 1914-1917, though it only concerns the American participation in the War 1917-1918. Hoover was enmeshed in Europe from 1914 on in organizing food aid for first Belgium and then France, and from November 1918 onward for all of Europe as far east as the Volga River in Russia. It was colossal undertaking that just got bigger.

Hoover worked for Wilson in several capacities, directly and indirectly in these years and some of the work was very intense, urgent, and truly life-and-death. I have traced some of Hoover’s astonishing humanitarian efforts in the review of the Hoover presidential library elsewhere on this blog.

The book was written forty years after the events it describes when Hoover was in his twilight years.

There is no indication that Hoover kept a diary at the time but he certainly kept copious files. In addition to the papers he himself had, Hoover also consulted reams of declassified official files to which he had easy access and he was assiduous.

There is no doubt that Hoover had a great admiration and respect for Wilson, as an intellect, as a moral champion, as a tenacious reformer, as a titan for work, as a man of personal rectitude, and more. He writes in glowing terms of Wilson in nearly each chapter.

The book compiles a great deal of detail on the points it touches. We read about the pounds of wheat in a shipment, or the number of delegates seated around the table at a committee meeting. It rehearses the arguments made in dark days when much of Europe was starving to death between 1917-1919. It produces an anatomy of the enduring antagonism between the French and Germans, the racial hatreds among the Balkan peoples, territorial ambitions of every country involved with the Treaty of Versailles. I certainly found some of that eye-opening.

Yet there is no insight whatever into the subject Wilson. In fact, apart from some laudatory paragraphs at the beginning and end of each chapter, Wilson only appears in the book to support Hoover, to agree with Hoover, to praise Hoover, to ask for Hoover’s help, etc. More than anything else it reads like a log of their business dealings from Hoover’s side.

Robert Lansing, Secretary of State for Wilson, appears here to be the absolutely straight arrow he is seen as in others studies of the time. I stress this because he has sometimes been belittled in Wilson’s shadow. Jack Pershing seems to have been the very man for the hour; when he spoke everyone listened. The rank of general ratified what he already was, a leader. In these pages Georges Clemenceau certainly lives up to his reputation as the Tiger, completely unyielding, hoping to destroy in the peace every German who survived the war. Winston Churchill is preoccupied with retaining the British Empire, despite espousing Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Colonel Edward House is constantly moving here and there though he holds no position, except as Wilson’s friend, a very small club that.

There are a few striking anecdotes. During the Armistice and the never-ending peace talks, American army officers, numbering a thousand or more, were sent all over Europe to keep track of the American food aid flooding across Europe. Long after they had been recalled Hoover got a personal letter from a lieutenant at a railway station in East Prussia who was still recording the train cars going past, asking if he could please get a new winter coat, apologizing for contacting Hoover directly but doing so because no one in the chain of command, long since disbanded unbeknownst to him, had replied to his previous requests. Upon checking Hoover found this dutiful lieutenant from that dreary East Prussian train depot had been telegraphing data to an empty office in Paris for eight months. Hoover made sure this forgotten man was recalled immediately and treated him to a luxurious few days in Paris before sending him to his unit to be demobilized.

Of greater moment are Hoover’s descriptions of the negotiations in Paris. More than ninety governments were represented in one way or another, each anxious to retain every foot of territory and every citizen it claimed, each ready to take more territory and citizens with a list of historic grievances to support expansion, each proclaiming Wilson’s Fourteen Points while violating them, none willing to make a single concession, each distrustful of all the others. What an atmosphere! Moreover, many delegations were even more deeply divided internally. The newly created Republic of Banat (look it up) had a fractious delegation of twelve who each insisted on going around en bloc because not one of them trusted another out of sight. To put one of them on a committee meant putting all twelve on. In other cases there were two or three rival delegations each claiming to represent, say, Osteria. Which one speaks for Osteria?

Rufus T. Firefly of ‘Duck Soup’ would be the straight man here. An ordeal indeed for any sane, rational man trying to do the right thing in such a ninety-ring circus.

Hoover defends Wilson from the common charge of being a hopelessly naive idealist with a compelling and convincing list of the material achievements Wilson made in Europe starting with ending the war, saving tens of millions of starving people, undermining the tide of communism, displacing some murderous tyrants who had risen from the ashes in Eastern Europe, establishing the International Court of Justice at the Hague, creating the International Labor Organization in Geneva, and founding the League of Nations which in turn did much forgotten good and paved the way for the United Nations and the international organizations that exist today.

But most of all Hoover credits Wilson with inserting into the vocabulary of international relations the language of rights, conscience, liberation and freedom that did not exist prior to his oratory. One might say that Wilson translated the emancipatory rhetoric of the the King James Bible into statesmanship, supplanting the existing language of gunboats, maps, spheres on influence, mandates, concessions, and survey lines. That Wilsonian rhetoric remains today. spoken by people with no knowledge or interest in the man Woodrow Wilson.

It is not an easy book to read for many chapters consist of quotation after quotation from speeches, committee reports, newspaper articles, diplomatic assessments, letters, and telegrams strung together with a few transitional remarks from Hoover. In hindsight Hoover has no second thoughts and no feel for the human drama all around him in those meeting rooms. But what raw material for novelist! Bring on Frank Moorhouse of ‘Grand Days,’ Georges Simenon of ‘The President,’ or George-Marc Benamou of ‘The Ghost of Munich.’

I hesitated to read this book since I found the Herbert Hoover in retirement portrayed the biography I have already read of him so bitter and unforgiving I supposed this book would be merely a record of that. Only a few asides did I perceive that rancor, primed to see it as I was. It would probably not trouble most readers who were not aware of Hoover’s ripened bile.

The forward by Senator Mark Hatfield adds little to the book.

Mariette in Ecstasy

Ron Hansen, Mariette in Ecstasy (1991). A novel that is recommended for adults, especially we sinners.

A short novel from a Nebraska writer that is partly a meditation on faith in the unseen and partly a study of human jealousy, envy, and love wrought in a spare prose that gives as much prominence to the sway of grass in the breeze as the characters in 60,000 unadorned words.

Mariette, a young postulant in a convent, is more religious, more faithful, more devout, more self-sacrificing than seems humanly possible. Several of the sisters conclude she has been touched by the hand of grace, while others suppose that she is an attention-seeking fraud.

A cult of Mariette begins and in the end it seems best to expel her. She is disruptive in punishing herself, in passing sleepless nights in prayer, in doing the work or two…

When confronted by skeptics, cynics, and disbelievers she submits to their depredations with a beatific smile.

Yet the skeptics, the cynics, the disbelievers, and the conservatives who expel her do so to preserve the delicate balance of convent community. No cardboard villains they.

The reader is left to wonder what the truth is about Mariette, or to wonder if the truth matters at all.

Perhaps Mariette is a saint and this is how saints are now reviled.

The time in the very early 1900s and the place seems to be Canada. But neither of those is important. The only reality is inside the convent.

Hoover Presidential Library – Recommended

I read a biography of Hoover (reviewed elsewhere on this blog) and found the man in retirement shown there to be unsympathetic and unimpressive. However that experience bore unexpected fruit. Having driven by the exit for the Hoover Library more than once on I-80 I decided to have a look next time. The time came in November 2013.

To anticipate the conclusion, I found the Hoover presented there far more interesting and complex than that sullen ex-president I had read about. I left with no doubt that Hoover was a great man (defined as someone who does things few others possibly could) and that his great deeds were done before he became president.

He took the oath of office in March 1929 and The Great Depression started with a cataclysm in November of that year. Yes, he tried to stem it and ameliorate it but with little Congressional co-operation (which FDR later enjoyed). He got run over by History.

What great things did he do earlier? He was in England when World War I started and was one of the principal organizers of a boat-lift to evacuate about 15,000 Americans from Great Britain. There he, and the world, found the seed of his genius. He was a dynamic and innovative organizer.

He then led a food relief program in 1914-1917 for Belgium (the neutrality of which had been ignored by the belligerents), negotiating with American, French, German, and Belgium governments to import food to Antwerp throughout the war. When the United States ended neutrality and entered the war, Hoover’s program expanded to France. At times the program was giving a hot lunch to three million people a day!

In order to attract the donations to support it, he identified himself closely with the program and poured in his own money (made out of mining in Australia), encouraging others to do so as well. They did, the Astors, Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, and their kind. Most of the money he raised from private donors. He asked millionaires for millions, and got it.

At the time and later this program elicited such an outpouring of thanks that it still reverberates. He made millions of friends for himself and for the United States.

When the United States entered the war, President Wilson asked Hoover to look after food at home. He did. There were meatless Mondays, milk-less Tuesdays, flour-less Wednesday, and so on, to conserve food (and so free manpower for war work and the army). He advocated the use of cooking oil in place of lard (used in packing cartridges). It was the patriotic duty on the home front to be ‘With Hoover’ in these practices. He was on the radio, in the newspapers, on the stump explaining why this was to be done. He was whirlwind.

When the war ended he went back to Europe to oversee European-wide food relief for France, Germany, Belgium, Austria and more. He was akin to a one-man Marshall Plan, raising money with one hand and ladling out soup with the other. His double effort in Europe saved millions of lives, earning the amity of a generation. Few other presidents made so many friends for the USA.

When Calvin Coolidge succeeded to the presidency, he appointed Hoover Secretary of Commerce. The whirlwind increased its speed! He was soon called the Secretary for Everything. Here he is at his desk in the museum.

But this cartoon from the explanatory video conveys much more. Click it and see for yourself.

File

He promoted vaccines for children, and raised the money from private donors to support it. He also drove a national program for standardization of everything from screw heads to milk bottles, arguing that the lack of standardization was crippling the economy and destroying private life because it consumed untold time and money. On one side of town milk bottles were one shape and size and on the other side they were different. He set up committees with governors and simply would not leave the room until they agreed on a plan to reduce expensive and time consuming variations.

So many of the standards we assume today, he made into reality. Too bad his like is not with us today to impose standards on the IT world.

In 1927 the Mississippi River flooded, killing scores and displacing thousands. President Coolidge recognized it as a national disaster and he sent one man to deal with it: Herbert Hoover. The next day tent cities and field kitchens sprouted along the shores, and hundreds of thousands of American slept on Hoover cots and ate a Hoover lunch (soup and bread). These were the first Hoovervilles. Here he was a one-man FEMA (look it up).

In 1928 Hoover walked into the Republican nomination and defeated Democrat Al Smith, a Tammany Hall wet who did not hold even the Solid South, such was Hoover’s command.

Then the freight train of HISTORY roared into view …..

The Hoover Library, the smallest of the Presidential Libraries, is wonderful.

The presentations are multi-media with plenty of buttons and bells for kids. It includes artifacts from his life, like European mails bags full of letters of thanks, and newspaper cartoons. It pulls no punches about the Depression and his inability to cope with it. Once again the National Parks Department sets the standard for conveying history briefly but in a compelling manner even to a jaded cynic with a made-up mind.

The two room house he was born in is on the grounds. From this modest beginning….

Pel goes West

Krimienologists take note. Mark Hebden, Pel among the Pueblos (1987). Recommended.

I read some Pel books in the 1980s and then moved on. It is a pleasure now to renew acquaintance with the irascible Chief Inspector Pel, the scourge of wrong doers on his patch of Burgundy. Clapping villains in irons was the greatest pleasure of his miserable life, that is, until he met the subsequent Madame Pel….

Hebden wrote a score of these titles and his daughter took over when he passed away.

In this entry Pel is in full flight, literally, since a particularly complicated murder takes him our of Burgundy. Shudder. But at least not to the sink of iniquity, Paris. But rather to Mexico City! For a man who had never left Burgundy it was a terrible experience. It got worse when he tried to eat!

Worse still when the inquiry stretched on and he feared he had not brought enough cigarettes. Though ever dutiful to Madame Pel’s injunctions, he did try to quit, several times a day.

I loved the Mexican detective Barribal who knew what to do and how to do it, though not the way Per would. Certainly not!

Meanwhile back in God’s country, Burgundy, the team gets on with nabbing some pretty tricky villains.

Along the way I found out a little about the Emperor Maximillan’s ill-fated time in Mexico, and the intricacies of auto insurance in France.