One of the many Westerns that Gregory Peck (1916–2003) made. That alone recommends it. The opening scene is superb and those that follow in the first act are on a par with it. Then comes the slide….

The silence, the eternal and forbidding landscape, the big sky, and the taciturn dialogue get it off to a good start.

Robert Forster steals some scenes from his mentor Peck, but ever gracious Peck rolls with it. Forster has since been in every television program there is but never equalled this turn.

Robert Foster waits.

Robert Foster waits.

There are some moments of humour as with the train ticket that it would take an IRS accountant to figure out.

Harder to take is that chiseled block of satin wood, Eva Marie Saint. That she is largely silent helps but the constant squeeze of the frontal lobes indicates her thespian range. When she speaks it is in whispers which I suppose is to add to the drama. It didn’t. (I admit that she was superb in ‘Don’t Come Knocking’ [2005] with Sam Shepard. Maybe with age directors were less inclined to limit her to eye-candy.)

Most of the faults of this film, however, lie with the screenplay and the director, Robert Mulligan (he of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’), and not the players. Where to start?

Eva, after ten years of (implied) brutal captivity, emerges with makeup intact and speaks English within five minutes as though nothing had happened. It is a strength of the screenplay that what happened is left to the viewers imagination and not stated, agreed. Yet she is none the worse for it.

Peck’s change of heart is a plot device and nothing more. It does not emerge from the events or his character. He says she can cook for him and Ned, but in the only scene of cooking, Ned, does not eat with them. Ned, too, is a plot device and meets the fate of a Star Trek Red Shirt in due course. That was obvious from his first appearance.

The aggrieved indian husband come to fetch home his son is granted no humanity. He is a spectre. Yet Peck has stolen his son as well as his wife. Why Peck chose to invite his wrath remains a mystery. This indian is supposed to be preternatural, yet when the showdown comes he is very visible and it must have taken practice to miss him with fusillade of rifle shots fired at him. He on the other hand drills Forester with one shot.

For a spectre he was none too bright. He lured the two younger men away but did not then go back to fetch his boy, who would have willingly come to him. Instead he prolongs the movie another twenty minutes. So that he can do the same thing again. In a Randolph Scott movie, made on a smaller budget, this kind of repetition did not exist.

But then Peck seems to lack smarts, too. In the last confrontation the indian is backlit in a doorway and Peck has a cocked rifle in hand, but waits politely for nemesis to enter the darkened room and shut the door so that they can slug it out in the dark. Go figure that one, Mortimer. Shouting at Peck to shoot, did not work. Indeed many of the interiors are too dark to see much.

Indeed the boy is likewise not granted humanity. He is a prop for Eva. That he might have collaborated with his father at the moment of truth seemed on the cards (joke, but to get it see the movie) but was forgotten come the time.

While decrying plot devices there is the dog. It is not present until needed for one scene, then is conjured as the watchdog. Ned’s reaction as that of a hardbitten frontiersman is a scriptwriter’s cliché.

The final contest between the two alpha males is a forgone conclusion. If that is all that was at stake, we all knew how that would end, and we did not need 1 hour and 59 minutes to get there.

I watched it on Daily Motion and read Roger Ebert’s contemporary review. He nailed it. But then when did he not?

Category: Film Review

‘7th Cavalry’ (1956)

The ‘7th Cavalry’ (1956) is about the aftermath of the Battle of Little Big Horn in June of 1876 when many plains indians united in the Great Sioux War. George Custer led his seven hundred troops into a trap of which he was warned by scouts and against the objections of subordinates. Though dead when this story starts, Custer’s pall lies over it all. He is lionised as a great leader, soldier, general, man, and paragon down to his yellow hair. On him more at the end.

Lobby poster.

Lobby poster.

The story is a combination court room drama, star crossed lovers (for once Scott gets the girl), dissension in the ranks, and a culture clash.

The tension arises because Scott was sent on leave by Custer just before he set out for the valley of the Big Horn River. It was verbal order and in a subsequent inquiry the suspicion arises that Scott had deserted and is lying about the order. (How anyone could believe for a nanosecond that Scott would do something so dastardly beggars belief.) The result of the inquiry is inconclusive.

Then comes an order from distant Washington D.C. to retrieve the bodies of the now honoured dead. Gulp! The war is on and that is a battlefield. There are seven hundred dead, only a few hundred remain in the fort, demoralised, frightened, and confused without the great Custer.

Who will do it?

I’ll go.

I’ll go.

Scott steps forward. (Of course.) He’ll go where the others fear to tread. With a detail of a few misfits not otherwise needed by the garrison, off he goes, tall in the saddle as always. The misfits include J. C. Flippen, Frank Faylen, and Denver Pyle. Familiar faces all. How this handful of misfits is going to bury hundreds and cart home the remains of the officers is anyone’s guess.

There are many vistas of the Alabama Hills where it was filmed, and much dissension in the ranks, which Scott deals with – wallop. Denver Pyle is ever reliable as a malingering whiner.

The high point of the picture is the negotiation at the Big Horn with the Sioux, who are forbearing, dignified, and conscientious.

The negotiation.

The negotiation.

The Sioux belief that the spirit of slain enemies nourishes their strength means the dead must remain in situ, especially Yellow Hair, the leader. Hearing this explanation from a Christian mission-reared Sioux, Scott says, ‘but you know that is all superstition’ to which the Sioux replies ‘just like your Christianity.’ Scott offers no reply. Superb. A moral and intellectual standoff between two well-meaning individuals who are now on a collision course.

Spoiler alert! Though guns are drawn and arrows slung, an ominous silence reigns. What Hollywood director would dare do that today? Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse have no wish to desecrate the field, but neither will they relinquish the bodies.

For the denouement have a look on Daily Motion.

It is a loose end that the messenger whose testimony finally and fully exonerates Scott does not seem ever to have delivered this testimony, and is killed without a comment. It was Harry Carey Jr.

George Custer had a great press, partly because of the efforts of wife and widow. He was careless with the lives of his men throughout his career, though of course he took the same risks himself, if that is any consolation. In the spring of 1865 when the ghost Army of Northern Virginia manoeuvred out of the deathtrap of its trenches at Petersburg, Custer ordered his cavalry division into a frontal attack on a scant division of emaciated infantry under Richard Anderson’s command.

Think about it. Men on horseback at a distance of several miles array in a line and then gallop over water courses of a wet spring and scrub bush toward a line of infantry men who, seeing them far off, had enough time to build defensive breastworks of fencing and wagons, unlimber and aim artillery, and to lock and load, take aim, and fire, long, long before the horsemen get close. An infantry musket had a killing range of five hundred yards. In the hands of a marksman the range was as much a 1,200 yards.

The feeble grey infantry killed a great many mounted bluecoats and broke the attack. It was madness. Custer’s command had the latest repeating rifles but even if an trained horseman could handle the weapon while galloping, the chance of hitting anything were near zero and reloading once the first seven shots were fired was impossible at a gallop.

The advantage of numbers saved the day, and the headlines, for Custer. His vastly larger force withdrew and flanked the Confederate line and compelled a withdrawal. How much better it would have been for the widows and orphans of the men in his command if the flanking move had preceded, and thereby obviated, the frontal attack. There was no Tennyson to immortalise this catastrophe. Yet the Custer publicity machine turned it into a great victory for him at Little Sailor’s Creek.

‘Ride Lonesome’ (1959)

This might be the best of the seven Ranown (Boetticher-Brown-Kennedy-Scott) movies. Why? The complexity of the plot and the surprise ending. Well, it surprised me and I thought I knew the formula backward. In fact, the end, the last scene is most fitting, though it left me wondering about a few things.

A lobby poster.

A lobby poster.

It starts as the usual story. Scott is the cryptic loner who appears from the dust to aid the damsel, Karen Steele, in distress. He has in tow the murderous James Best, who, as always, makes one’s skin crawl with his servile, whining, inept, craven villainy. Moreover, Scott with Best and Steele falls into the company of a dubious pair, played superbly by Pernell Roberts and James Coburn, both outlaws themselves but not in Best’s class. The shadow of a future confrontation between this pair and Scott is obvious both to the viewer and to the parties. This was Coburn’s first film role.

Roberts and Coburn confer.

Roberts and Coburn confer.

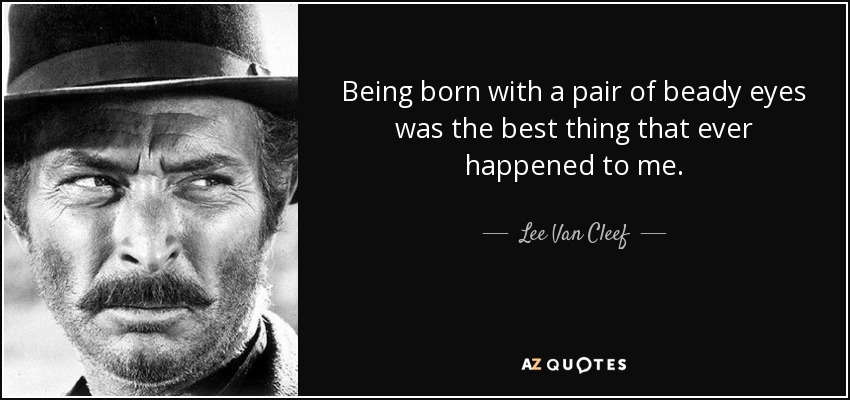

Best brags repeatedly that his big brother, the redoubtable Lee van Clef will be coming to his rescue and kill them all. I would certainly fear Lee VC, as he liked to be called.

Lee Van Clef on his film career. Regrettably most directors asked no more of him than to squint those beady eyes.

Lee Van Clef on his film career. Regrettably most directors asked no more of him than to squint those beady eyes.

Before that confrontation they have to elude the raging Mescaleros, Apache Indians, who are raiding and have killed Steele’s husband. This is one occasion in the series when the indians are a mere plot device and given no explanation. This party of five had better make tracks to escape the indians and Van Clef.

Yet, at Scott’s insistence, they take the long way, travel in daylight, and cross open country rather than sticking to tree lines and ridges, moving at night. No effort is make to cover their many tracks. It dawns on Roberts that Scott wants to be caught, not by the Apaches, but by Lee van Clef, because…

Roberts and Coburn have a powerful incentive to take Best away from Scott and deliver him to the law, for then they will gain amnesty for their own earlier and lesser crimes, and so be free to live an ordinary life. Roberts is magnificent in wrestling with this temptation. Understated and taciturn per the screen play but endowing it with depth and delivering it with timing. Coburn as a naif is the perfect foil to his ruminations.

Scott never has doubts and so never ruminates: Best is a murder and he must be delivered. He is Scott’s prisoner and so he will deliver him. End of story.

Well not quite because there is a confrontation with Lee Van Clef, the one villain in this series who is not fleshed out but left a cypher, as Van Clef usually was.

Then comes the surprise.

Then comes the ending.

The end.

The end.

‘It figures,’ says Roberts in another of his diamond lines tossed over his shoulder.

‘Comanche Station’ (1960).

My homage to Randolph Scott continues, after an hiatus. This one is near the end of the series, and the formula shows through it. Scott, as ever is a loner somewhere, sometime after the Civil War in the West. Reticent, stoic, confident, straight as the Indian arrows he dodges, here he is st age sixty-two.

A lobby poster.

A lobby poster.

His path crosses that of a damsel in distress, and she finds the enigmatic Scott compelling, yet he a distant and perfect gentleman and she, usually, is another man’s wife. To spice up the mix there must be villains, and to the credit of these productions the chief villains are never Indians, though they are there, but other Europeans. The villains are thrown together with Scott and his charge in hostile circumstances and, in this case, they have to cooperate to avoid the Indians, but we all know a showdown is coming at about minute 70. We all know who will prevail, but the skill of the writer and director still manage surprises through the supporting players like the damsel and the naif.

Inevitably, the naif grows to admire Scott and the naif’s commitment of the Villain-in-Chief wobbles. Inevitably, the damsel misunderstands Scott’s motives and only gradually sees through that misconception to his noble core. Thus there are several nested stories. The overarching narrative is to survive the hostile circumstances and return to a town. Within that we have the menace and final confrontation with nemesis. Nested still more are the doubts of the naif and also the dawning realisation of the damsel that Scott is a knight without armour. When all these themes have played out, inevitably Scott rides off alone. Oh, and inevitably Scott wears a neckerchief. Don’t know why. To hide a scar?

Another credit to the production is that the villain has personality, and is not just the CGI cipher villain now in Hollywood productions. In this tale the villain is Claude Akins, who combines a rude charm with a bottomless evil.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

I was disappointed to see Akins’s name in the credits when it rolled off ‘Daily Motion,’ the website from which I streamed it, because I remember the caricatures he used to play on television in the 1950s and 1960s but here he projects a distinct individual who is not all bad and yet is – in a different sense – all bad. He is aided in his villainy by the ever reliable Skip Homeier, who is knocked off too early for this connoisseur of slim-balls. The villain in this formula usually has two acolytes, and third in this party is Richard Rust, otherwise unknown to me, who is a naif who has fallen into bad company and knows no way out. The list of chief villains Scott bested in these last films is impressive, starting with the most complex, Richard Boone, Lee Marvin, Pernell Roberts, Lee Van Clef, and Warren Oates, and many others.

Indians, I mentioned Indians and they are here and on the warpath, but they are also shown to be honourable. The Comanches kept the deal they made with Scott at the outset. Moreover, that they are making war is, we learn, precipitated by the murder of many of their women and children by still other bad Europeans off camera. In fact, they are victims who are lashing out at those to hand.

Scott made at least a hundred films and perhaps eighty of them were Westerns. He got type cast but he also liked that. He rode on to the screen time after time with a self-confidence and poise born from having been through it all before, again and again. It is no wonder Sheriff Bart invokes him in ‘Blazing Saddles’ (1974).

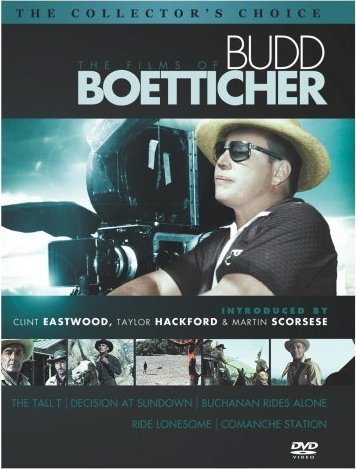

Seven of the films Scott made at the end of his career have been the object of my veneration in this homage. Why these? Because by that stage in his career, with the astute management that made him a millionaire many times over, and too old to remain under contract to a studio, he was a free agent who could decide what he wanted to do and then do it. This he did with some long time friends and associates producer Harry Brown, director Budd Boetticher, and writer Burt Kennedy. They were made in the Alabama Hills on the east side of the Sierra Madres. Each films includes many elegiac passages as the cast travel through the area. All of them also put the life-and-death human concerns against a timeless and limitless backdrop that shows just how small those concerns are in the ultimate scheme of things.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Clint Eastwood and Martin Scorcese and others have both expressed their admiration for these films. Look for them on You Tube. It is exactly this sort of the film that George C Scott refers to in ‘They Might be Giants.’

Scott’s career culminated in one of the greatest Westerns, ‘Ride the High Country’ (1962), Sam Peckinaph’s first western, featuring a near-sighted Joel McCrea with an arthritic Scott, the ingenue Mariette Hartley, the drooling Warren Oates, and more. The gossip is that Scott and McCrea flipped a coin to see who would play which part, one a huckster and trickster and the other a pillar of unassailable integrity. Both were pitch perfect and both quit on that note. I will also sneak a peak at one of his defining films that etched itself into my prepubescent mind, ‘7th Cavalry’ (1956).

‘The Best Years of Our Lives’ 1946

The other day by accident I came across a reference to this film somewhere or other, and much of it came back in a rush. That is a tribute to director William Wyler who got a performance of a career out of the block of wood known as Dana Andrews. A screenplay by that remarkable wordsmith Robert Sherwood is understated. and often pensive. There is much that is not said because it cannot be said. But it weighs on each of the three principle characters, Fredric March, Dana Andrews, and Harold Russell.

That jolly upbeat title belies a taxing story which I doubt I would have the fibre to watch today.

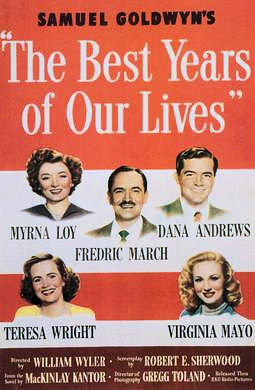

Then there is this jolly lobby poster which in no way prepared audiences for what they were to see.

Then there is this jolly lobby poster which in no way prepared audiences for what they were to see.

These three Odysseuses survived to return when so many others just like them did not, an indelible fact each carries everyday; moreover they return to a new and different world. They have changed and the world has changed, too. The three Penelopes have also changed, and that enters the equation.

Every viewer will remember Homer (Harold Russell) and so we should. How daring Wyler was to cast a paraplegic to play a paraplegic. It broke the unwritten law of Hollywood of showing reality.

Harold Russell

Harold Russell

Even more daring was Sherwood putting the word ‘divorce’ in Fredric March’s dialogue. At the time and place it was simply not a word said in public. That word was the reason the film was not shown in some places. Perhaps the supposition was that to hear the word ‘divorce’ would drive couples into divorce.

The ghosts are many and mighty that overtake Dana Andrews. Andrews, in a long subsequent career, much of it in B-movies, never equalled his portrayal of confusion, consternation, and dread, no shouting, no hysterics but driven deep none the less. That scene when he once again sits in that seat is indelible.

Andrews driven deep within himself.

Andrews driven deep within himself.

Perhaps that was Wyler’s genius, to have an actor who would not over do it. But just let it happen. It happened.

If this is too cryptic, Mortimer, watch it. Those who have seen it, they will remember it well. Those who have not, have an experience in store that has no equal in contemporary cinema.

‘Maigret’s Dead Man’ (2016)

This is the second episode of Maigret with Rowan Atkinson in the title role.

It is a masterclass in drama. Every scene is a tableau. Nothing is extraneous. The characters are rounded, not stereotypes. All the loose ends are resolved.

Marvellous.

When a crisis demands every police officer’s attention, Maigret insists on pursuing what seems in comparison a trivial case. Why? Because it has become almost personal.

A man in a panic had telephoned Maigret at the office saying that his wife, Nina, knew Maigret…. But he rings off, later to be found murdered. But Maigret knows no woman named Nina. Nor does he recognise the dead man when he is found. Who is Nina? And who is the victim?

This murder has the earmarks of a gangland slaying, and accordingly the powers that be see no reason to investigate it. But Maigret cannot let go. The victim personally asked for his help and Maigret feels obliged to do what he can now, even if it is too late.

What is refreshing about this, as with the first, instalment is the quiet plod of police work. There is no shouting, no histrionics, no flashes of insight, no scientific magic. Instead there is Just plod and more plod, piecing the puzzle together one part at a time. Even when Maigret is proved right, there is just a shrug without triumph.

Atkinson projects the authority, the calm, the impenetrable inwardness of a Maigret who has the strength to remain silent.

The direction is so confident and so demanding that viewers, well these viewers, were gripped by the slow movement, like a very slow tango with complicated steps that seem to go nowhere and yet fascinate.

All the heavy artillery in the opening scene soon makes sense. That the provincial police officer overreacts is hardly surprising. I also liked the respect accorded to him rather than the ridicule routinely written into most cop shows for such individuals. He is in over his head but who would not be so in the circumstances.

A quibble, however, in the novel Maigret slowly takes over Chez Albert. When he finds and gets in, he noses around and then it seems too late to go home and so he beds down there for the night intending to return to home and office in the morning. Then the next morning a punter knocks the door for coffee, and Maigret obliges. Then another punter arrives…. Margret soon calls Madame Maigret, Louise to the cognoscenti, to come and help out. He becomes a stand-in for the absent Albert.

It is the essence of Maigret to enter into the life of the victims and that is very well realised in this film in several ways, including this stay at Chez Albert, but also the betting slips and the lemon frappé. Atkinson performs these moments of abnegation well, very well, when his Maigret surrenders his persona to the milieu.

One powerful scene occurs when an exhausted and so far frustrated Maigret returns home to 54 Boulevard Richard Lenoir where an anxious Madame Maigret says a man is waiting for him in study. It is obvious at a glance that this visitor is one very hard man, a villain, but he has come to help, and after they talk, Maigret hands him a drink. It sounds like nothing to describe it but the humanity, the compassion is all the deeper for being unsaid. In other versions this scene would have handled much differently with some more, superfluous dialogue and perhaps a ponderosa and gratuituous witticism, as often in the Gambon versions, but not here.

Purest will say that Atkinson is not a doppelgänger for Maigret, and they would be right. He does not have the bulk of Maigret. Michael Gambon fit that bill perfectly.

I said no stereotypes at the outset, and that has to be qualified. The villains are one-dimensional. They are elemental forces that rip through the lives of those caught in their path.

The second to last scene with the bejewelled girlfriend of the instigator is far too pat for this viewer. A woman so easily satisfied with baubles would not bow to reality so readily.

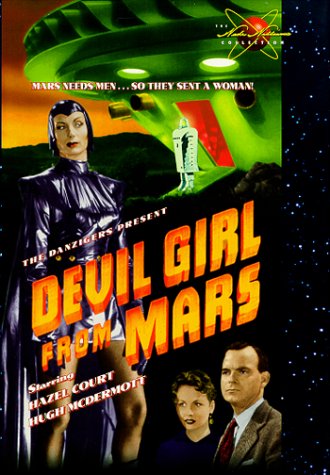

‘The Devil Girl from Mars’ (1954)

Inspired by ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951) the prodigious Danziger Brothers — Harry and Edward — turned their hands and low budget to sci-fi in this effort. It offers inspired casting and a prescient screenplay, and we watched it the other night. Well I watched it twice. to get the subtlety.

Devil Girl, indeed. Patricia Laffan is THE movie. When she is on screen there is tension, there is presence, there is drama and when she is not, there is none of the above. On her more below.

In the remote Scots moors an odd assembly takes refuge in a lonely inn. A married couple run the place, baby sitting a grandson, with a handy man, elderly Jim, and girl of all work who is mainly seen at the bar. With the winter approaching the only guest is a beauty from the big smoke and then a scientist with a newsman in tow arrive to investigate the strange lights in the sky. An escaped convict also insinuates himself in the group. Otranto Inn is now ready for the night ahead.

The scientist and newsman provide masculine leadership by debunking the worries of the women about those strange lights in the sky. ‘Just your imagination, my dear.’ They seem to have forgotten that those lights are why they are there in the first place. By now we know better. After the predicable confrontation with the convict, instant jealously over the beauty, and more condescension, Nyah appears!

Can that woman make an entrance. Seven times by my count. Shazam, indeed. The part of Nyah was made for Patricia Laffan, who is cool, calm, implacable, and pronounces her diabolical purpose with diction that would bring a smile to the twisted lips of Professor Henry Higgins. Her vowels are so round; her consonants are so icy.

With a black leather body suit, a cat-like skull cap, a Darth Vadar cape, a mini-skirt avant le mot, and a ray gun, she has it all. Then there is the spaceship and within, Chani, the tin-man. (I thought she was calling him ‘Johnny’ which seemed awfully informal for Nyah, but on a long flight, well….)

Nyah has no time for small talk, nor, I suppose, for a shipboard romance with Chani; she is all business and the business is men!

The near-sighted, shuffling Jim with the feeble manner of an emeritus professor is a poor physical specimen, she declares. Poof! That’s it for Jim. He is no longer a drain on the taxpayer.

On Mars the emancipation of the women led to open warfare between the sexes. The females won, usurping the political power of the men. This eventually led to the sexual impotence of the planet’s entire male population. (Remember Louis Malle’s ‘Lune Noire?’ Look it up, Mortimer.)

She is Hillary Clinton! Come to emasculate the Republicans! ‘Go, girl’ we shouted from the couch! Grab ‘em by you-know-whats!

Just like the Republicans, the first reaction of the men is amused disbelief. What, after all, would a woman know!

After a few object lessons, the next reaction is brute force. Why negotiate when a good whack should fix things. Think of the 7MATE demographic. Efforts to beat sense into her backfire.

Stage direction. The telephone lines are down. The only automobile won’t start. Darkness falls. They are isolated and alone. They will have to work together to overcome this one woman who threatens life as men know it. Gasp!

But wait, what is the problem?

She wants men. Call for volunteers, Nyah! But stand back to avoid the rush!

The screenplay wobbles. At times she wants spirited and unwilling men and at other times the docile tweenager seems to be preferred. This Devil Girl has trouble making up her mind. How like a woman in the stereotype of the era.

The screenplay is inane and most of the acting, especially the male leads, ranges from wordy to wooden and back. The special effects are far from special, even by the standards of 1954. The tin-man clearly had no tin or much of anything else barely making it down the ramp much like the late Jim.

Lobby posters on the interweb give three women top billing. How rare is that! How rare was that in 1954.

Patricia Laffin, per the biography on the IMDB, was ‘a statuesque and striking actress with vaguely reptilian aspects, at once sinister and alluring; a smile that was as much a sneer and a commanding, imperious presence suggesting innate superiority with a delivery that was at once sardonic and disdainful.’

Stop there. That is Nyah.

Nyah is precise, frigid, fiery, and languid. This woman could be hot and cold simultaneously.

Laffan did not fit the pigeon holes of the time and was relegated to supporting roles as a villain or an eccentric. Our loss. (But she stole the show from Peter Ustinov in ‘Quo Vadis’ (1951) before hitting warp speed as Nyah.)

The men had their turn in ‘Mars Needs Women’ (1967), but Tommy Kirk in a wet suit one size to large for him just does not have what Nyah had! He did call for volunteers and not even Annette came. Mickey Mouse, indeed.

Both can be found on You Tube.

‘Arrival’ (2016)

We idled away a hot and humid Sunday afternoon at the Newtown Dendy to see ‘Arrival.’

First contact with aliens is a gold standard in science fiction. Many examples are shoot ‘em ups from ‘The War of the Worlds’ to ‘Independence Day’ and their kind. Nothing more will be said about these sort.

Before going to ‘Arrival’ I checked an on-line trailer to see if it met our preliminary standards, little or no CGI and little or no shoot ‘em up. CGI is Computer-Generated Images, which are a fatal virus in most movies these days, an easy substitute for thought. It passed these two tests which rule out most of the dross from the dream factory.

Off we went. What’s to like?

First and foremost its lead and star is a woman, who is neither glamorous nor trying to be a man. Amy Adams plays a skilled linguist named Dr Louise Banks. What she does is listen and think. That is a tough ask for Hollywood: thinking.

The usual currency for thought is the full face close up with wrinkled frontal lobes, but we get little of that here. Instead we get a lot of flashbacks, flash forwards, or flash sideways. I am not sure which, and will return to this point below. Adams does it well, and carries virtually every scene, certainly every scene worth watching.

The movie has pace but it is in no hurry. There is movement but not those crazy camera cuts loved by action directors who have never been in action themselves.

There is an intellectual puzzle — how to communicate with these aliens, who are very alien — placed in a high-pressure context.

We loved all those alien zeros with their minute differences.

They were incomprehensible. That is the mystery. What a relief from the NRA-approved Hollywood films, made by bleeding heart liberals, where all solutions lie in a gunsight. Bam! See any of the recent Star Trek movies. Incomprehensible is better than splat.

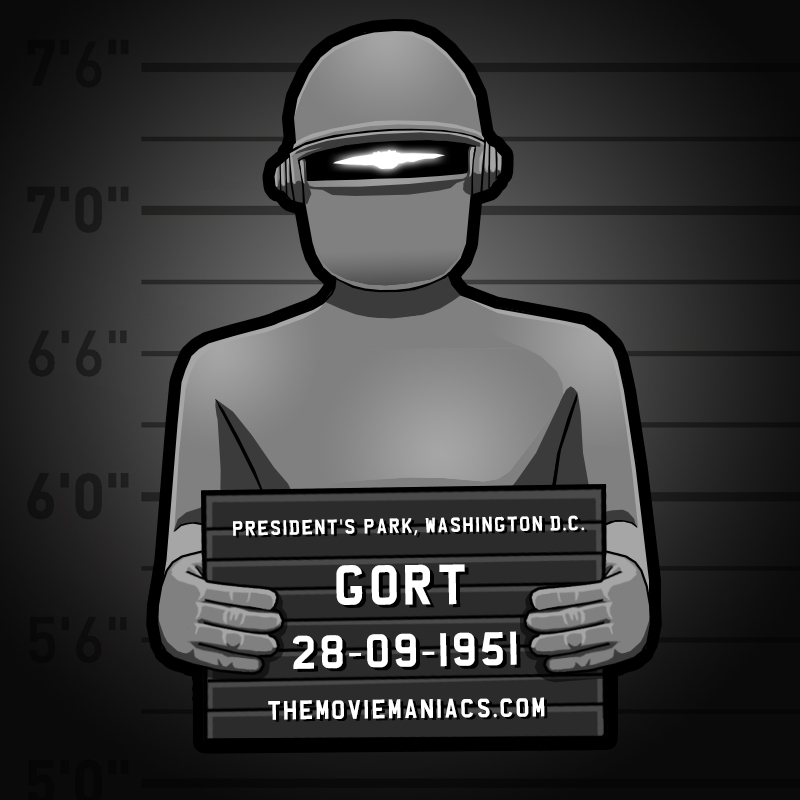

In the original ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951 [and 2008]) Patricia Neal had to say ‘Gort, Klaatu barada nicto.’ It worked. Whew!

Gort.

Gort.

To do that she had to get to the right place passed the guards, overcome her own fears for herself and her child, and remember the incomprehensible message, and deliver it by rote to the scary robot. That was hard. Especially when his light went on. See above.

Dr Banks’s mission is infinitely harder. With all the same fears that Neal had, she has to figure our first what it means and then how to say it in zeroes. That is some tough exam. It is even more difficult than understanding something said by the Cheeto President-elect.

The biggest theme is time’s arrow which seems to be the governing narrative.

However, neither of the professional reviews I read from the ‘New York Times’ or ‘Sight & Sound’ mention it. All the flashes, back, front, side, seem to be about the simultaneity of time about which we might find out more in a sequel three thousand years later. (To get the point, see the movie.)

I also liked the understated Forest Whitaker for whom dealing with aliens is another day at the office. Indeed, he is almost catatonic. Of course, it is unlikely a mere colonel would have command of such a situation, though most generals would try to avoid the likely career-ending duty. The massive overkill of the U.S. response rings all too true. The motto of the Pentagon seems to be ‘Nuke the jaywalkers!’

Not so likeable were these things.

The dark cinematography defeated some of the exercise. I never did get a good look at Whitaker or anyone else. I expect it will be even more difficult on DVD.

See what I mean?

See what I mean?

The helicopter landing at the start is gratuitous, distracting, and unbelievable. The helicopter is seldom the fastest way to travel because its airspeed is nothing special, especially when in civilian airspace full of other aircraft. The noise distracts from the dialogue. It is unbelievable that a pilot would land in a wooded residential area at night.

‘They have to see me,’ Dr Banks says ripping off her Hazard Suit (coloured to remind us of ‘Space Odyssey’ I suppose) mask for no discernible reason than that its time to get that Hollywood star our of the glare of the plastic mask.

That the hero is bold where others hesitate is a tired trope trotted out here several times. Cemeteries are full of such bold wanna be heroes who never made it to celluloid fame.

The nicknames ‘Abbot and Costello’ come from nowhere and went right back there. While we silverbacks got it, did anyone else, or have these two execrable comedians been resuscitated? I hope not. Unless it referred to the two Australian politicians Tony and Peter.

The screenplay has its share of clichés. Top choice is the Chinese general who has mastered McKinsey-speak when he says that Dr Banks ‘reached out to him.’ I have heard that too many times from cliché-speakers who did the training course. At least he did not insert a meaningless ‘actually’ in his remark. The scene is good and the point is part of the mystery but all of that is deflated by this McKinseyism. The air went right out.

As expected, there is a hot headed soldier, though here the idiot is a working stiff who acts on his own with a few buddies, where in reality it would be an educated and overpaid general in D.C. who wants to blow something up to get another star. Think Sterling Hayden from’ Dr Strangelove’ (1964) and you have the reality of General Curtis LeMay, a one time vice-presidential contender. The aside with Russ Limbaugh, the most shocking of jocks, was perfect but added nothing here.

If the pointless tracking shots, and empty rooms were cut, we could lose thirty minutes and not notice it. It is too long and indeed the longer it goes, the less the tension. A slow leak is still a leak.

I have to enter a plea for the chain of command. In this movie a Chinese general acts without the authority of the Communist Party. Never. All those purges Mao unleashed were partly aimed at cowing the army and keeping under the thumb of the party where it still is. Nor would the Director of the CIA call the shots as rendered here. There is a president to do that. Gulp.

The director, by the way, is Canadian Denis Villeneuve who has many other credits that I have not seen.

Denis Villeneuve

Denis Villeneuve

Seeing this reminded us of the other First Contact movies. Chief among them is ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ as mentioned above in which a passive alien ambassador is murdered by a trigger happy grunt to the cheers of Russ Limbaugh and his kind. Then there was Jodie Foster in ‘Contact (1997).’ A cut above the mill, this one is for its intelligent screen play. In a class by itself is ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).’ As is ‘Paul (2011),’ though this not really first contact it is unexpected contact. There are also many instances in the Star Trek canon before the franchise descended into CGI shoot ‘em ups. Some of these are very thoughtful when thinking was still valued out west.

Star Trek: Beyond (2016)

This is Year Fifty. It all began in September 1966 and I was there to see it on that night in September. All Trekkies will have to see this, whether they like it or not.

What’s to like?

The cast members are superb simulacra of the Originals. That is partly looks, assisted by make-up, but also mien, accent, and attitude. The actor’s craft is to inhabit another person and they do it with ease. Bones is perfect and so is Kirk. Spock is more nebbish than the Original. Uhura is more wonder woman, and Scottie is more excitable, but these are quibbles.

The distribution of lines and incidents to the ensemble cast of the crew. Scottie, Sulu, Uhura, Spock, Bones, all have more than one moment in the camera’s sun. Only Chekov misses out, in my memory. It is not all about Kirk, as too many episodes of the Original were.

There are some zingers to be sure. Throw aways lines like ‘they say it hurts less if it is a surprise.’

The women hold their own. Uhura may answer the phone once or twice but she also delivers some surprises.

Jaylah’s literal-mindedness was amusing. Though good to have on side in a fight, Jaylah seems to be there mostly for the make-up.

The idea of heavy metal music can be used as it is in the movie was marvellous. I am trying to steer clear of a spoiler here.

The explicit tribute to the Originals in the last scene with Spock was humble.

What’s to not like?

The repetitive shoot ‘em ups are incomprehensible and pointless and there are many of them, at full volume.

The holes in the plot are sufficient to pass Africa through. The villain’s backstory is vacuous. The Franklin is … What’s the word, it is impossible to suspend disbelief.

The Federation’s own responsibility for its problems is a worn out motif in Star Trek but here it is again.

The variation are the returned veteran was the theme in the predecessor (‘Into the Darkness’) but here it is again in a slight re-configuration. These writers need to read more to find inspiration, say Jane Austen or Anthony Trollope to broaden the horizons and deepen the insight.

The theme about unity and strength is said a couple of times but left empty. Recalling as I do all those conversation with thesis writers where I would say integrate, e.g., Michels’s Iron Law, and the writer would say ‘But it is on page 46’ and indeed it was mentioned there but it was not developed and integrated into the text. Neither is the unity-strength couplet here. It is a case of ‘words without the music.’

The army of CGIs dispatched in the action scenes bring the franchise closer to the comic book status of Start Wars.

Kalara, the bait, with that strange head more or less disappeared from the story.

Summing up.

At two hours and two minutes it is about thirty-two minutes too long. The interest and intelligence of the story do not sustain the duration. It is out of balance.

The effort put into those CGIs and choreography of the action scenes might better have gone into the script.

What made ‘Star Trek’ a keeper in 1966 was that it was not just another shoot ‘em up on television where there were plenty others of that ilk. There were genuinely intellectual puzzles, like ‘Court Martial’ and morally challenging episodes, like ‘The Devil in the Dark’ and ‘The City of the Edge of Forever.’ In its current embodiment most problems are solved with a fist and a phaser. Such a contrast to the Original, e.g., ‘Nomad, ‘Return of the Archons,’ or ‘The Doomsday Machine’ where some thinking had to be done.

The Original was made for adults and ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’ brought that to fruition. The present version is regressing to an audience of prepubescent boys which is probably inevitable since that likely describes the filmmakers from writers, directors, and producers.

‘Trapped’ (2015)

A ten-part television series from Iceland. Nordic noir without the computer graphic images of gratuitous gruesome gore that typify far too much of the genre. IMDB rates it at 8.2.

It kept us coming back for more. Each fifty-minute episode ending on some crisis, and each subsequent episode beginning with a recapitulation. Slow and old fashioned.

What’s to like?

The pace is measured and low key. No shouting, table banging, or the other crutches mentally impoverished screen writers and directors use to distract from the superficiality of the work.

The setting is great travelogue. Snow, mountains, and fjords, oh, and plenty of ice on the north coast of Iceland.

The Iceland’s weather is a major character that directs and limits what the human agents can do.

The interaction of the public and private lives of the characters in the small town which is cut-off by a storm.

The three small town cops, each different, make a good team, fallible though each is.

The crippled watcher. But we got too little of him.

The several wheels within wheels which were neatly wrapped up in the end.

The redemption of the falsely accused and imprisoned boyfriend.

‘The devil entered me’ said the grieving grandfather.

That most of the trouble was all homegrown and did not come on the ferry.

The mixture of languages, Icelandic, Danish, German, French, and English.

The cannibalistic media. Another tired trope but I am not yet tired of it.

What’s not to like?

The big city cops are a trope, arrogant, easily satisfied, and incompetent.

The ex-wife’s boyfriend is ever present, leading to the conclusion that he will figure in the plot, but he does not. A blue herring.

The ferry captain’s change of heart was pat.

The police commissioner in Reykjavik was built up to be important in the story and then dropped.

Andri’s backstory was a boring distraction as they always are. This is another crutch.

We found it on SBS On-Demand. Hooray!

But we found it very difficult to find on the telly. The TV screen search function could not find itself! Nor could it find ‘Trapped.’

The iPad app is great. It was easy to find ‘Trapped’ on it but we wanted to watch it on the big screen in front of the easy chairs. The app does not communicate with the television as far as we could see.