Another entry in this long-running series. Gordianus is caught up the revolt of Mithridates VI of Pontus against the Romans in Anatolia.

His one-time tutor Antipater is in trouble in Ephesus and Gordinaus betakes himself to find out the situation.

But Mithridates has just driven the Romans off the mainland of Asia Minor and occupied Ephesus in triumph, and is secretly preparing for his really big barbecue. [Anyone who knows the history, knows what is coming, and those who are ignorant can remain that way.]

Goridnus hatches a hare-brained scheme to enter Ephesus disguised as a Greek and rescue Antipater. The whole scheme turns on Gordianus keeping his mouth shut, since his Latin accent says R – O – M – A – N! And all Romans are persona non grata in Anatolia. Gordianus is usually a motor-mouth, and will most assuredly blurt out something, sooner or later.

Even before he gets there the plan unravels. It seems just about everyone he meets en route from Alexandria, to Rhodes, to Ephesus knows his plan. In short order, he is suborned into acting as a Roman spy.

Meanwhile, he worries about his ailing old dad back home in Rome, which is embarking on another round of elite circulation via murder and mayhem in a civil war. Elections might not be cheaper but they are marginally less destructive.

The to’ing and fro’ing in the eastern Mediterranean from Alexandria to Rhodes to Ephesus is amusing, but Gordianus is just too serious for me. Worry, worry, worry, he is always worrying and in the brief moments when he is not worrying, he is lusting after his wife to be, Betheseda. He is not the life of the party is Gordianus. There is always a dark cloud over his head. He takes himself and everything about him far too seriously. I pined for Decius when I read these. Where is that wastrel with a bad word for everyone? (He is the protagonist in John Maddox Roberts’s SPQR series.)

This entry in the series seems laboured, a short-story bulked up with long passages from Antipater that do not advance the plot, deepen characterization, or lend much colour, though they show the author’s ingenuity to be sure.

Steve Saylor

Steve Saylor

And the denouement with the Furies is likewise ingenious. The Furies are a bad crew with plenty of wrath to go around.

We spent a day in Ephesus in 2016 and so I had to read this title.

The library.

The library.

The sacred way.

The sacred way.

The amphitheatre.

The amphitheatre.

Ephesus is a remarkable site for the preservation of so much of an ancient city on such a grand scale. Sooner or later some mad men will no doubt blow it up to prove their manhood to….themselves, since no one else cares.

Category: Krimi

Morgue Drawer Four (2014) by Jutta Profijt.

A rollicking krimi with a pair of mismatched buddies, one an extroverted sleek lowlife car-thief with a four letter-word vocabulary and the other an introverted roly-poly PhD scientist in Cologne Germany.

Pascha is a rev head who loves cars, and stealing them is great fun, the more so getting paid to do so. Then one night after stealing a particularly desirable rocket car, on order from the Russian mafia, he finds in it…. Something he should not have.

He pays for his discovery and that brings him into contact with Martin, the super nerd. Their efforts to communicate and, reluctantly, to cooperate are a hoot. One is street wise to the Nth degree and the other equally book wise.

With false starts, snits, and pouts they slowly combine to find a killer, and find both more and less than they bargained for. Along the way they come to respect the assets each brings to the mission. The setting of Cologne, that cathedral city in Germany, offers much to’ing and fro’ing around town. There is some travelogue as each shows the other his haunts.

It is hard to say more without a very large spoiler.

This is the first in a series and I hope the author can keep up the joie de vie.

‘The Ivory Grin’ (1952) by Ross Macdonald

A gritty tale of unrequited love(s), madness, and sacrifice from the stylist of noir krimis. Raymond Chandler had a ear for dialogue, while Ross Macdonald has a jeweller’s eye for descriptive metaphors and images. Lewis Archer is his avatar.

While the novels obey all the conventions of the genre in its time and place, it also turns them inside out. The PI’s boredom counting flies on his office windrow is interrupted by a femine fatale, as required, but this one, despite the diamonds and furs is barely a femme at all. A very mannish woman is she. Archer’s emphasis on her lack of feminine qualities is partly the everyday sexism of the era but it also turns out to be a pivot in the plot.

As always with Macdonald, everything from the color of the sunset to the hats impart texture, reveal character, and unwind the plot. Nothing is ever wasted in his novels.

This is a triangle of three families, locked together by one of the offspring. Bess is literal when she says she loved him to death. Lucy, the loyal nurse, sees more than she ought and cannot get out of the vortex. That manly woman is normal compared to her brother, who has a gun. Assorted other lowlifes pass by, but the worst of the lot is the quiet suburban doctor.

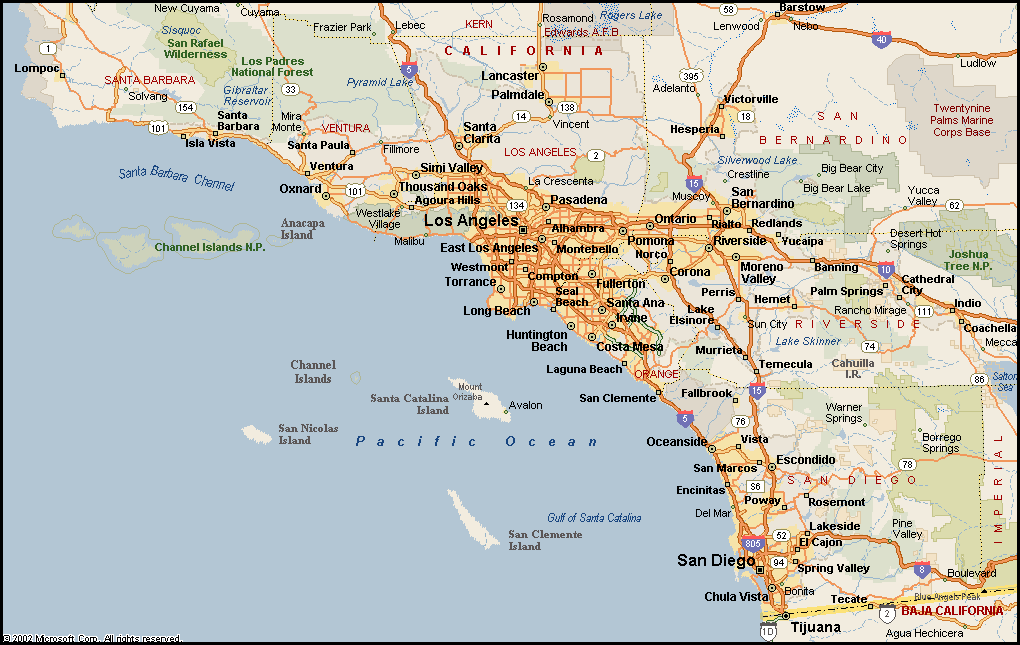

Archer country

Archer country

There are some innocent bystanders along the way, Alex the love-sick boy who pines for nurse Lucy and the love-sick girl Sylvia, who pines for playboy Carl, and who becomes in a convolution of the plot Archer’s client.

I still have the paperback copy of this I read In the 1970s but I re-read it on the Kindle. I turned to it to find something to read after a series of misfires with annoying, self-indulgent, padded, and pointless krimis. If only Jane Austen knew what she had spawned when she told would-be writers to to write about what they know. Far too many only know the IKEA catalogue. Why continue the search for quality when I know right where it is.

Sometimes Macdonald’s metaphors and images come so thick and fast that they create a traffic jam in the reader. Sometimes the psychologizing gets in the way of the momentum of the story. But these are the prices of admission.

Archer is named for Sam Spade’s deceased partner, Miles Archer, who believed in fifty dollar bills.

Macdonald’s krimis are hard boiled in that they are unsparing In word and deed. The villains are villainous with little of no veneer. Often the mystery is less who dun it than why dun it. That is the psychological depth that distinguish his works.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

Ross Macdonald, who spelled his name with a lower case ‘d’ though the spellchecker disagrees.

This one is the fourth of eighteen Archer novels over a thirty year period.

At least one of his krimis had a rave review on the front page of the ‘New York Times.’ The book was ‘The Underground Man’ in 1971 and the reviewer was that southern novelist of note Eudora Welty.

Yet none of his novels was ever awarded a paramount krimi prize like the Edgar. Figure that out, Mortimer.

Had I to pick one, it would be ‘The Blue Hammer’ in 1976, his last completed novel. I recall still how eager I was to get it and to read it, taking it with me when I went jogging to read a few pages while catching my breadth.

A mature work. in it he is not trying so hard to crowd in metaphors and there is less speculative psychologizing by Archer, while retaining the descriptive richness, the psychological depth, the ambiguity of motivations, and the equilibrium of the moral balance. In his books, unlike life, the world bends towards justice of a kind.

Perhaps Macdonald wrote one book eighteen times, as has been said, the same story of twisted love, divided loyalties, wayward offspring, mental imbalance, irresponsible parents, each magnified by a the glare of money in the prism of California sunshine that blinded the individuals to their own deeds.

By volume eighteen the biggest mystery is Lewis Archer himself about whom the reader learns almost nothing. He is a lens that reveals the story of those around him. By his actions we can see he is an inveterate loner, but one who warms readily to some women he meets for their physical and intellectual charms and vulnerability; he is dogged, and hard working. He wears a hat which he sometimes takes off. In one story we note he drives a light blue car, in contrast to his dark blue mood. At least he has a name, unlike Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op.

There is less about Archer in the eighteen titles than there is about Philip Marlowe in one of Chandler’s books. Archer has no backstory. The reader is not manipulated into feeling sorry for him. Why should I, he certainly does not feel sorry for himself.

Archer reports on the dirt under the carpet of the American Dream in the golden sunshine of Southern California, and it is very dirty. Yet he meets honest people whom he likes, and some he even admires. Say in contrast to the BBC’s Christopher Foyle whose world is populated entirely by liars, cheats, and murderers, often dressed in gold braid with aristocratic titles and important government jobs, Foyle’s is a world without hope, but Archer’s world has hope, and that is what keeps him going.

‘The Adventures of Tom Stranger, Inter-dimensional Insurance Agent’ (2016) by Larry Correia.

The title alone was irresistible, and my resistance is futile, quite often.

It opens with the destruction of Earth and then it gets worse!

Fortunately, Earth had an All-Catastrophe policy, no exemptions and no deductible, with Stranger and Stranger Insurance, and Tom Stranger appeared in time to put things right, dragging in his wake one very reluctant intern. (President John Wayne took out the policy and arranged for eternal payment of the premiums.)

Tom offers the best customer service in the universe, and he means that literally. Anything less than a ten our of ten is failure, and Tom does not fail, not even when confronted with dinosaurs sporting Nazi insignia. (Part of a Trump delegation.)

The intern thought a six-month stint in insurance would be, like you know, easy. As a Gender Studies major he had not actually bothered to read any of the print, fine or actually otherwise, but, like, was waiting for the movie, actually, like, so he had no idea, like, actually what he had signed on for actually. Well ‘no idea’ might be a generalisation. ’Thought’ is not the right word. No thinking occurred. The intern is a thought-free zone.

Moreover, this Gender Studies intern was from…yes, it gets worse, Chico State, where beer stains on tee-shirts are, well, like, cool, way cool actually.

Tom would like to return his intern from whence he came, but duty calls and redeeming a Gender Studies major from Chico State, now that would be a challenge of inter-dimensional magnitude.

But first, Tom and the intern find themselves in Nebraska where they must battle the ultimate evil. Gulp!

Tom is rated at 104.3 Bear Grylls while the intern is a puny, 0.4 BG. The Bear Grylls rating refers to what it would take to kill BG. It is an inter-dimensional standard. [Love it!] Tom can man-up, or rather Bear-up, to the ultimate evil there among the corn fields, but he will have to shelter that puny intern who is less than half a Bear Grylls.

Larry Correia

Larry Correia

NO SPOILER.

It is two hours of spoof, like a long skit from SNL in its heyday, read by Adam Baldwin who manages all the inter-dimensional voices, including Muffie back head office. Discerning readers may remember Adam Baldwin as Animal in ‘Full Metal Jacket.’ It is high octane all the way.

The corporate speak, the obsession with the customer experience ratings while ignoring customers, the constitutional inability of an insurance company to pay a claim, the CVs of the policy-holding political leaders encountered along the way, the numb brain of the intern, all of it rings true. How can this be fiction in a world where Donald Trump is reality? Go figure that out.

It has been a while since I used Audible so I had another look and found this corker. I listened to it while pumping iron and pushing pedals at the gym. I call it a krimi because there are plenty of crimes, but in a boring old book store it would be sci-fi.

‘Four for the Boy’ (2005) by Mary Reed and Eric Mayer

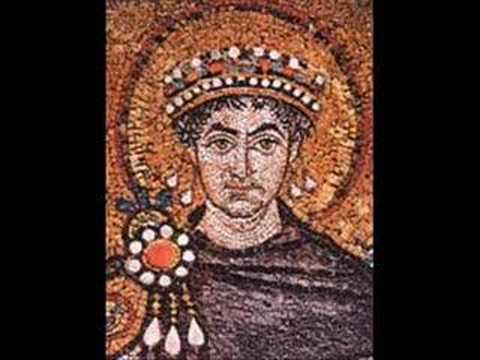

The fourth in a series set in Sixth Century in the Constantinople of Justine and Justinian, emperors of Nova Roma. Our principal is John, whose mercenary background has brought him to Constantinople … a slave. He bristles at his status but makes the best of it.

Amid much palace intrigue John, as the Emperor Justin is passing the rule, reluctantly, to his nephew Justinian, is assigned to an excubitor. Felix, he from the Teutonic woods, to investigate the blatant murder of a rich citizen in a church. The Emperor Justine designates them, perhaps more to slow, than speed the investigation for John is after all a slave, and no citizen is required to speak to him. Felix has only a middle rank, poor Latin, and is not the sharpest knife in the drawer. The city’s Prefect resents their intrusion and fobs them off with other duties.

Justinian.

Justinian.

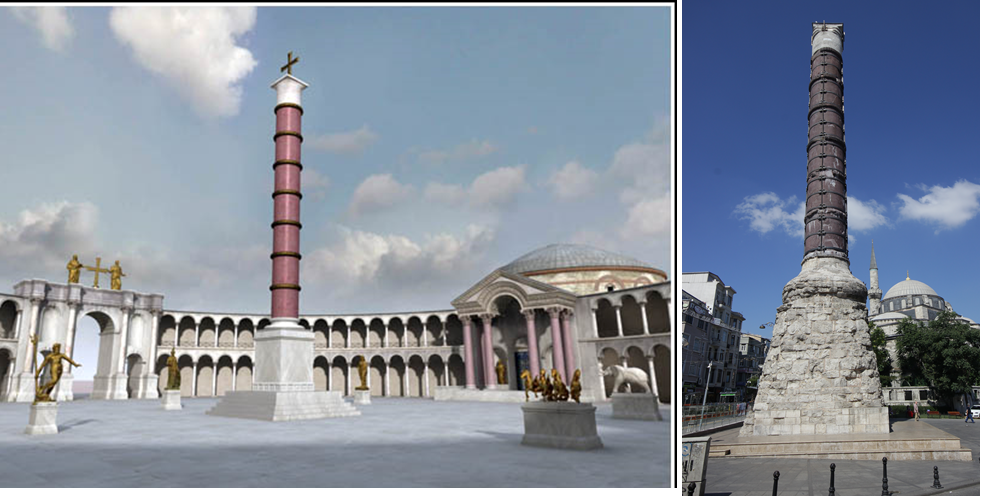

On their fools’ errand, they go here and there in Constantinople from the Hippodrome to the Golden Horn, to the Bosphorus, to Constantine’s column, to the Great Palace. Each time I shout out, ‘I’ve been there!’

Constantine’s column as it was and and it is today.

Constantine’s column as it was and and it is today.

Two such low level functionaries have little access to the great and good, and the few they meet are quick to tell them that. But they do have more access to the panoply of slaves and servants of the great and good, from door men, to kitchen hands, to fishermen who supply the food, to prostitutes. While many of these humble folk are too careful not to say much, sometimes what they do not say, is itself noteworthy. That is the conceit of the work.

I have read two other entries in this series. Each is packed with period detail which is salted throughout the work. There are no long expositions, just everyday asides and comments. Felix is an excubitor and we learn as we go that means he is a palace guard. We are spared an exposition of the nature, organisation, and origin of excubitors that would be inserted by some other writers to discharge their learning. Here the hand is light and the exposition is slight; the emphasis is always on the matters at hand.

However, John’s backstory lingers more than it should for this reader. We would be better off to find out what kind of man he is through his actions, pace John Stuart Mill, than be prompted by his unfortunate biography. My empathy for such contrivances is zero these days.

The title makes sense in the end, though the villain springs from no-where. But it does tie up all the loose ends.

Eric Mayer

Eric Mayer

Mary Reed

Mary Reed

While this is a foreign and, in many ways, a repellant world, the authors do not attempt to explain or justify it, they just present it in its own terms. There are the fantastically rich and the poor who live on the streets, just as in Reagan’s America, and in Obama’s too. Indeed we have such dwellers in Sydney these days. All in all, the authors bring to life a cast of characters from mute beggars, clever scientists, vain artists, working stiffs, court intriguers, wealthy fops, as well as Emperor Justine and soon-to-be Emperor Justinian and she who will be obeyed, Theodora.

Many unusual terms like excutor are used and there is a eight-page glossary at the end for those who must know before turning the page.

‘The Shadow Walker’ (2006) by Michael Walters.

An exotic krimi set in Mongolia as it emerged from the Red World in the 1990s.

Where is Mongolia? Having seen so many episodes of Eggheads with contestants who do know where their elbows are, this map is included.

A series of murders, each more terrible than the previous one, in Ulaan Bataar galvanises attention at the highest level, the more so when a British technician is one of the victims in a five star tourist hotel, and then a senior police officer.

Genghis Khan, a landmark mentioned several times in the novel.

Genghis Khan, a landmark mentioned several times in the novel.

The minister of justice dispatches the one man he can trust to co-ordinate the police efforts, Nergui, he of one name. Into this brew steps a British police officer, Drew MacLeish, sent, as a sop to the slain technician’s family back home, to contribute to the investigation.

Ulaan Baatar

Ulaan Baatar

It is a nice context and premise. There is some travelogue in and around Ulaan Bataar, and the Gobi desert. The centrifugal and centripetal forces of the ancient traditions and new opportunities for wealth are portrayed. All of this was interesting reading.

Ulaan Baatar

Ulaan Baatar

The exposition is far too wordy for this reader. Too many long speeches about either the perils of modernity in Mongolia or the backstories of the principals, which always bores me to tears. In this case Nergui’s backstory is laid on with a trowel; he a man among men, a gentleman and a scholar, a preternatural athlete…. Oh hum. Sainthood can only be a matter of time.

The Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert

Let’s get to the plot and as it unwinds we better learn of the characters. I almost wished for Mike Hammer, so appropriately named. You always know where you stand with Mike, under his heel. He spent no time talking about anything but the beating he was giving you.

The author cleverly turns the language barrier into an opportunity. When Nergui speaks to natives in Mongolian, Drew studies the expressions and body language and makes inferences from those observations. The conceit is that body language and face expressions cross the cultural barrier. Perhaps they do not. Likewise, Nergui uses the presence of the British chief inspector Drew as a lever to secure cooperation from officialdom, both Mongolian (in the ministry) and British (in the embassy).

Michael Walters

Michael Walters

Much of the tension springs from some tired clichés about politics and politicians. The unscrupulous behaviour attributed to politicians in general in these pages can be found in any middle to large organization. There is, surprise, nothing unique about politics, except its ready exposure to such clichés. I did not find any explanation of the title.

The denouement is deus ex machina. [Look it up, Mortimer!]

‘The Disappeared’ (2002) by Kristine Rusch

An adult and thought-provoking sci-fi krimi. Recommended for adults.

I found myself squirming several times when reading it, tempted to put it aside, but then I realised it was getting under my skin and that was the point. Chapeaux!

Moreover the characterisations of the human protagonists are credible and the plot twists and turns follow the two rules of Sherlock Holmes: there is a logical explanation to everything and nothing is as it seems. That all adds up to a four-star review.

In a future universe there are many species who trade and cohabit the same planets with multi-cultural laws to regulate dealings and to settle disputes. The distant Multi-Cultural Tribunal issues absolute and binding rulings and warrants and it falls to the local police to enforce them, no questions asked.

Many misunderstandings arise in business transactions and in cohabitation, and there are many active warrants, which never expire. The punishments the other species apply are, well, inhuman. For several of the species apprehension of a violator is a matter of honor and no effort or expense is spared in pursuit. In some alien legal codes, ignorance is no defence. A guilty mind is not necessary.

One generation of entrepreneurs sees in this situation a market gap. Secret companies emerge to help those targeted by a warrant to disappear (and start a new life elsewhere), a relocation service for the guilty, not for witnesses.

There are many sources of tension in the setup. There are several mysteries for the police to unravel. Negotiations with two separate sets of aliens each sensitive to the least cultural slight. There is the Earth Alliance government, remote and inaccessible, for which keeping the peace by adhering to the strict letter of the Multi-Cultural Tribunal warrant is paramount. The fate that awaits those apprehended does not bear thought.

The more so because several of the species in the Tribunal act on inter-generational justice. Like Chinese emperors of old and North Korean dictators of today, they have justice to the third, fourth, fifth degree, or more. Huh? That means the punishment often falls on relatives of the culprit, relatives who themselves did nothing and may not even know the culprit. For those who shelter from the news, it is common in North Korea for the sins of the father to fall alike on daughters and grandsons. When the father is executed so are his children and grandchildren to eradicate the line. Now imagine being an officer who rounds up the babes in arms for execution.

In this novel one of the felons to be surrendered is a baby. Another is a woman who cut down a tree, only later to be told it was a sacred relic. In the law of that alien world ignorance is no defence. Still others did in fact kill a member of another species in a drunken fight over money. And so on. All of the felons in this novel are guilty but that does not make any of it easier.

All of this comes to a head because a second generation of entrepreneurs has emerged and decided to increase value for shareholders by selling-out the disappeared ones to their pursuers.

While it is illegal to help felons disappear, it is perfectly legal to sell them out.

What a beautiful scheme. The credits flow in drowning out the screams of those who disappeared and now are found. Disembowelment, babies surgically modified to become alien, condemnation to mortal slave labor, or shot on the spot are among the punishments for the humans apprehended, all compliant with the ruling of the Tribunal. The job of the local police is to hand over the felons.

Those who had successfully disappeared for decades are now sought and arrested. The human police execute the warrants of several alien species on a Moonbase. So many that they cannot keep up. One asks why low level police officer negotiate with aliens, but the answer is perfectly sensible bureaucratic logic. No more senior official wants to get involved in such distasteful and explosive business, so it is shoved down the line. That will be familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation.

This is the first is a long-running series.

K. K. Rusch.

K. K. Rusch.

It is well written though I flipped some pages quickly as there is nothing special in much of it, and too much musing by some of the characters for my taste, but mercifully shorn of mindless descriptions that bedevil so much of the krimi genre these days. The dialogue is functional. The author does not try to describe the aliens apart from some vague outlines, the Rev, the Disty, and the Wynin. Just enough to make clear that they are alien, not humans with heavy make-up. That is altogether an intelligent decision.

I particularly liked the senior investigating officer DeRicci and her one-way ticket approach, and the Retrieval Artist in the last pages. The last scene was a surprise and a nice coda to much that went before.

When I read the title ‘The Disappeared’ my first thought was all those who have disappeared from military regimes in Latin America, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, and…..

A sobering reminder that there are worse governments than the local mob.

Krimi Fans, sub species Maigretistes.

Put aside suppositions and watch Rowan Atkinson as Maigret.

My membership in the Maigret Fan Club began way back in high school French class, and has continued through irritated readings of Penguin translations which take many liberties with the original text, compounding the sin by boldly proclaiming that they are faithful when it is plain that they are not. I have read all the stories, including ‘Maigret’s Memoirs’ in which Jules Maigret recounts his association with one Georges Simenon.

While I enjoyed MIchael Gambon’s turn at Jules Maigret some years ago, and recently watched them again, they made many of the characters into cardboard to accentuate Gambon’s Maigret. Gambon was a perfect fit for Maigret physically. Rowan Atkinson is not the doppelgänger of Maigret but his performance is compelling for its simplicity, its inwardness, its intensity, its prism for the emotions of others, its humanity.

‘Maigret Sets a Trap’ is a gem. It is quiet and slow, qualities that are sure to bore some viewers, but for those with an attention span, it repays attention. The crimes are terrible, the press is irresponsible, the politicians are desperate, and through it all plods Jules Maigret. He has nothing to say to the representatives of the press who joyfully blacken his name. When assailed at a dinner party about the incompetence of the police, he says nothing. Indeed, this Maigret says even less than Simenon’s, and the silence is itself a message. When threatened with censure by his superior, Maigret persists in doing things his way. He says nothing, no theatrics, just more plod.

Margret chooses, as he knows he must, to tell the family of victim, and it is agonising. Almost nothing is said, but the weight of responsibility on Maigret is palpable.

The trap fails, and the minister has to have a scape goat. But the trap did produce a button, and from that button a mighty Niagara eventually flows. (A reference to an aside of Sherlock Holmes on the volumes that can be found in scraps of evidence.) It is ground pounding, endless interviews, triple cross-checking, meticulous examination that finally locates the culprit. No flash of semi-divine insight, no laboratory magic, no table pounding or shouting. Just more plod.

We all know Maigret will prevail, yet there is tension, mainly produced by the silences. Maigret’s techniques of interrogation consists largely of silence, patiently waiting to be told. The desire to tell someone, that is a theme in many of the Simenon’s Maigret novels, sometimes it is boasting, and at other times it is confession.

The team of Lucas, Maigret’s alter ego, muscle man Janvier, and the boyish La Pointe are established.

As Sean Connery IS James Bond, so Jean Gabin IS Jules Maigret with that weathered face, scarred by combat service with the Free French.

As Sean Connery IS James Bond, so Jean Gabin IS Jules Maigret with that weathered face, scarred by combat service with the Free French.

Georges Simenon, one of Belgium’s most successful exports.

Georges Simenon, one of Belgium’s most successful exports.

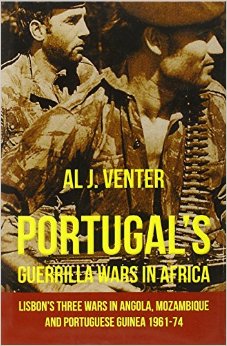

José Cardoso Pires, ‘Ballad of Dogs’ Beach’ (1982)

A Portuguese krimi set in the 1960s during the dictatorship of Prime Minister Antonio Salazar who ruled from 1928 to 1968 with both velvet glove and iron fist. A body washed up on a beach and the police arrive. The corpse is that of a man, slightly disfigured by the water but clearly murdered, who is identified as army Major Luis Dantas Castro, a soldier with a distinguished record in Portugal’s many African wars.

The homicide squad opens a dossier, but then it seems PIDE is involved. PIDE? Policia Internacional e de Defensa do Estado, the secret political police. Some months before Dantas had escaped from confinement for plotting the overthrow of the regime. Much of the novel is almost documentary as Inspector Elias Santana studies the dossier. Footnotes add to the verisimilitude.

The inspector is an introspective, methodical, and repressed fellow who speculates, even fantasises about might have happened. Was Dantas killed by government agents? By his own comrades in conspiracy? Or because of sexual jealousy? Elias tries to reconstruct Dantas’s last few weeks of life, working from scanty evidence. Elias uses his imagination to create the scenes at the conspirators’ hide-out that led up to the murder.

Sad to say that the novel is cryptic, hard to follow at times, and of most interest to those curious about Portugal of the time. And they were interesting times.

José Cardoso Pires

José Cardoso Pires

In the 1960s the Portuguese Army chaffed at the isolated and insular dictatorship, in part because it was under-equipped and under-funded for the ambitions of its officers and also in part because the regime neglected its restive colonies which the army had to secure. At the time the Portuguese Empire included Goa and two other smaller enclaves in India, East Timor, Macau, Angola, Mozambique, Sao Thomas, Cape Verde, the Azores, and Guinea Bisseau and…. The one that got away, Brazil.

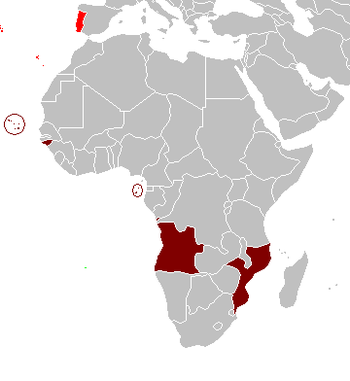

Portuguese Africa

Portuguese Africa

Between 1960 and 1974 Portugal was engaged in three colonial wars in Africa in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea Bissau.

While other European powers had been, often reluctantly, withdrawing from colonial empires, Portugal, neutral during World War II, had not. By 1974 it had 220,00 soldiers in combat in Africa. The financial, social, and political impacts in Portugal were extensive. The combined populations of Sydney and Melbourne come to about eight millions, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Imagine them together sustaining three wars in northern Asia without allies.

Salazar was an intellectual, an economist by education, who conceived of Portugal as a pluri-continental, multi-cultural nation. The colonies were provinces which were at a distance from Portugal, but represented in the parliament. Salazar wrote papers and gave speeches on these themes which taken together with Portugal’s undiluted Roman Catholicism, largely untouched by the Enlightenment, made it the New Jerusalem for the entire world. He termed it the Estado Novo, or the New State, a model for all others to follow. This backward, repressed, impoverished, and inward looking country, according to Salazar, was the only pure expression of the West! (Compare to Albania for its communist purity at the same time.) Like many intellectuals, he apparently mistook words for deeds, and was content to talk, not act.

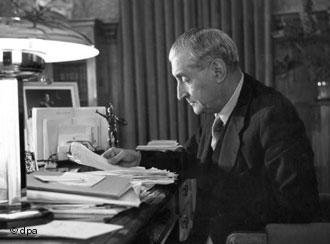

Antonio Salazar

Antonio Salazar

During the two generations that he dominated Portugal, it was sealed off from the world. Border control was stricter than in Berlin before the Wall. The PIDE had a reputation like that of the Statsi though not the same kind of massive budget.

Travel was restricted and all travellers had their baggage searched. not for drugs, but for books that might be illicit. Karl Marx was at the top of that list but also on it were Thomas Paine, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and William Shakespeare.

A special literature evolved, cut down to Portuguese size. Huh? All the great works were translated and edited to remove the big ideas of autonomy, liberty, human rights, majority rule, women who were not barefoot and pregnant, judicial review, the rule of law, equality, these were all removed. For example, Marie Curie was excised from science texts. The Beatles’ music was banned. Foreign movies were cut for screening to remove ideas as well as sex.

Even Spain, ever a frenemy, was viewed as lax and kept at arm’s length.

Brazil was a problem. The regime wanted trade and cultural relations with it because it was and remains the largest Portuguese-speaking country but though it had its own dictatorship, it accepted Portuguese exiles who set up opposition groups there. Because Portugal allowed first the Allies and then NATO to use the Azores it was tolerated and left to its own devices during the Cold War. Perhaps Salazar even hoped that one day Brazil would return to the Portuguese embrace.

There were incidents including the high-jacking of the Portuguese cruise ship the Santa Maria in 1961 by some army officers in mufti. They captured the ship with the aim of going to Angola, amid much publicity to attract supporters, to set up a government in exile. They were soon apprehended as pirates, and instead went into exile in Brazil.

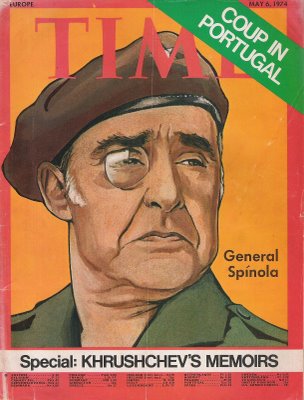

When the African colonies rebelled with some encouragement and very little support from the USSR, the overstretched Portuguese army lost. Betrayed by the regime, now presided over by Salazar’s heir Marcello Caetano, another economist, junior officers (captains, even lower in rank rather than the Greek colonels) effected a coup d’état, and into the breech stepped the flamboyant General Antonio de Spinola (1910-1996), who had had combat successes in Africa yet was known to oppose the wars. The coup was set in motion by a signal, namely a certain fado ballad in which a carnation was a token between two lovers was played on national radio at a specified time. Thus began the Carnation Revolution.

The regime, seemingly eternal the day before, fell in one stagger. The result morphed into democracy in Lisbon. Spinola wore a monocle, ergo flamboyant. There are a few parallels to De Gaulle’s return during the Algerian crisis in France, but with this difference, Spinola was committed to ending the wars and he did. It was said then and now, that only he could have done this. He had served among Portuguese volunteers in the Spanish legion with the Germans at Leningrad, and had led successful military operations in the Portuguese African colonies. His family was connected to Salazar. As a result, he had credibility and prestige with the old guard, but at the same time he was a hero to the captains and earlier he had made clear in writing his opposition to the wars at the expense of his own career.

‘The Murmuring Coast’ both the novel and the 2004 film comment on Portugal’s African war(s) in a restrained way. The film screens on SBS now and again.

True his word, General Spinola ended the colonial wars from one day to the next and negotiated settlements with the African colonies, made contact with China about the future of Macau, and left Timor. Thereafter as Portuguese democratic politics went left in the heady days, now largely forgotten, of Euro-Communism, Spinola went into exile himself to Brazil, where he plotted against the democratic regime with a small group of acolytes in a pathetic coda for a larger than life figure. He did return to Portugal and lived the rest of his days in quiet retirement.

There seems to be no biography of him in English.

‘The Murder of Mary Russell’ (2016) by Laurie King

Another entry is a brilliantly conceived and executed series featuring an ageing Sherlock Holmes and his bride, many years his junior, but nonetheless his equal. She had to be to displace ‘The Woman’ from Holmes’s mind. Baker Street Irregulars know who the ‘The Woman’ is. I am not sure that Mary Russell has yet learned about her in this series.

There is a lot to like about these krimis. There is energy, movement, period detail, and most of all the characterisations of Russell and Holmes but also others whose path they cross from the cantankerous Mycroft, to ingenious Billy Mudd, to the redoubtable Mrs. Hudson who has much up-stage time in this entry.

Much of this title concerns Mrs. Hudson’s past live(s) and even that of her parents (we are spared the grandparents) told in a novella within this novel on the order of a Charles Dickens novel of the dark, noisome, and sinister Victorian London, with a long side trip to sunny Sydney. All of this is well done but of no interest to this reader, and probably not to many others, who like this reader, follow the series for Holmes and Russell. I thumbed those pages quickly on the Kindle and there were a lot of them, a lot. Holmes does eventually make an appearance there, too little and too later for this reader.

However the action returns to Russell and Holmes and crackles when it does. I found Russell’s message to Holmes unfathomable. Nor did I follow the reasoning about the flight. But who cares, that is like quibbling about the colours on a racing bicycle as the rider drives it up L’Alpe d’Huez.

Laurie King

Laurie King

Mrs. Hudson has had her due in an another series, e.g., Martin Davies ‘Mrs Hudson and Spirits’ Curse’ (2005) and many others.

The conceit in this series is that she solves most of Holmes’s cases with her below stairs contacts but lets Holmes upstairs think he has done it on his own.