A krimi from the industrial city of Tampere (population 364,000) in the forests of Finland.

Winter in Tampere

Winter in Tampere

Detective Saraki Koskinen probes and pries, in between outbursts of temper. He is wound up as tight as the clichéd spring. Divorced, he combines workaholism with fitness fanaticism to fill in the hours. He jogs, well, races, at midnight or later and rides a bicycle everywhere, as fast as he can. Consequently, he sweats a lot and needs showers and clothes to change into, and these he carries. He is organised, but some things always go wrong and he is caught in embarrassing situations, which occasion outbursts of temper as compensation.

There is a murder victim, a paraplegic. Who would want to murder a cripple? Perhaps anyone who knew this bad tempered man, whose affliction just made him more aggressive and violent, having perfected ways to use his mechanised wheelchair as a battering ram, especially against people who underestimated him in that chair. In the assisted living home everyone has a bad word to say about him: Loud, noisy, drunk, violent, rude, inconsiderate at all hours, starting to sound like a teenager.

Then there is an a second victim, an elderly man who lives near the home but not in it, and who was near death from cancer. Then a third, another resident of the assisted living home, a woman whose paralysis was so great she could barely speak.

Are the three murders related? Are the three victims connected somehow? Are these perverted mercy killings? What does the perpetrator gain from the first, the second, and the third death? Is the second murder part of the sequence or a coincidence?

The novel is a police procedural and the squad interviews and re-interviews all the residents at the home, the visitors, the staff, the suppliers, and neighbours without getting traction. In the course of this members of Koskinen’s squad argue with each other about overtime, office supplies, and the assignment of duties. It is by no means a happy crew. Seldom can anyone say more than two words without interruption, or someone stomping out of the room in anger. Koskinen is not the only one wound up tight. As the leader he seems unable to calm them down.

Koskinen has yet another new intern as a temporary secretary-receptionist who cannot stifle the urge to rearrange his papers neatly. Her well-meaning but misjudged intrusions lead him to one burst of temper after another, which seem to wash over and off her. Just as well because there are more to come.

In addition, his team members bully one junior detective, and though Koskinen is dimly aware of it, he cannot figure out what to do about it, and being a man he cannot ask for advice. Bullying in this case seems to be an outlet for the frustration of the others vented on the weakest member of the group. The frustrations are about the case, about the malaise of the police service, about personal irritations, about anything and everything.

When some uniformed patrol officers forget to report the discovery of an abandoned wheel-chair, there follows another outburst of the well-known Koskinen temper. That the patrol officers forgot because they were involved in a particularly gruesome traffic death only slightly reduces his outrage.

After each outburst, he realises he is not in control of himself, wishes he had not done it, and cannot apologize. See, life-like.

Meanwhile, there is much about Finnish manners and morēs that I found interesting. But even more about the paraplegics and quadriplegics at the assisted living home, their ways of coping with life after paralysis, of finding satisfaction (food, drink, drugs, sex), and the relationships among them.

In the hope of a speedy resolution before the media hysteria leads to an intervention from Helsinki, the police chief points to an intruder as the likely culprit, but Koskinen, in the best tradition of the genre, is sure the villain is in the home or closely associated with it. Indeed.

Though that conviction is undermined by a close study of who had access and who has keys to the building. There is an official list for each, both short, and a real list, both much longer. On the real list are taxi drivers, prostitutes, delivery drivers, close relatives, medical specialists who hand the keys to locums, and more.

As is compulsory in the contemporary genre, there is much about budget cuts in the police but also in the assisted living home. There is no staff member in the home overnight but rather an elaborate electronic security system to monitor the residents and the building. The latest in IT. But in a crisis it signals a security agent who has a twenty-minute drive to get there, if the weather is good, more if there is rain, wind, or snow, as there is nine months a year. According this agent arrives too late each time.

Meanwhile, when not pedalling or racing, Koskinen sees television interviews with the national Police Minister talking about further budget cuts in policing, and outsourcing more and more police duties to contractors with such IT setups. This lifts his morale, not.

As always I find keeping track of such unfamiliar names a challenge, but the author very clearly distinguishes and delineates the characters and that helps a lot.

Seppo Jokinen

Seppo Jokinen

There are many other titles in this series featuring Saraki Koskinen in Finnish, but this seems to be the only one translated into English as yet. I do hope more are on the way.

Category: Krimi

‘Kill me Tender’ (2000) by Daniel Klein

When the teenage presidents of Elvis Presley fan clubs start dying, the King notices, and the more he looks into these deaths, the darker they become. Looking is one thing, acting is another, and for that he mobilises his posse and makes an alliance with an unlicensed doctor, an African princess (well, that is how Elvis sees her), and himself in the person of an Elvis impersonator, and also the five-year old brother of one of the victims.

What a treat!

This Elvis is polite, considerate, compassionate, colour-blind, and tenacious. He has to be because he comes across some very rough customers in this tale. While he is used to being demonised for the evils of rock-and-roll, in this case it is literal!

His music is a bridge that spans some of the racial and social divides laid bare in his inquiries. Though he finds more in common with the poor blacks he meets than with the uptight whites. They both have Bibles to hand, but in the former case it is a comfort, while in the latter it is weapon.

When Elvis sings a hymn, well, who cannot listen, who is not transported, who does not believe the sincerity of his tears? Many, many, do believe, but not all starting with the very angry father of one of dead teens, who blames Elvis twice over, once for being white, and second for that satanic rock-and-roll. The first victim that comes to Elvis’s notice is black.

The upright, uptight whites are even more difficult to fathom behind a facade of Calvinist politeness. While they accept their daughter’s death as God’s will, they do not accept Elvis intruding into the matter. But he cannot stop himself. These children had somehow connected to him and now they were dying. Was it because of him?

As for the local law, as much as they suck up to the King, there is no interest in stirring. Well, except for one sheriff who sees big headlines in arresting Elvis for these very crimes. The plot thickens.

Into heady brew comes a criminal psychologist. Elvis has thumbed through her book without much comprehension but he then telephoned her. That conversation in itself is worth reading the book. ‘Hello, this is Elvis Presley….’ Then there is Elvis’s huge, tattooed, menacing cell mate when the aforementioned sheriff arrests him who styles himself ‘The One.’ He seems to have more insights than even the glamorous New York psychologist who arrives (book contract in her brief case, suspects Elvis) to lend the King a hand.

When the going got tough, Elvis’s posse was more trouble than help, and he finds strangers more help than those on the payroll, including some of the jailbirds.

Elvis was a class act and this book vindicates that in spades.

The book offers a very sobering and painful account of the life of a celebrity like the King. He is a prisoner of his frame. He cannot walk down the street, drive his car to a park, visit a cemetery, book an airplane ticket in his name, or go to church. If he does, he is mobbed by fans and the media. HIs every move in public is splashed across the headlines and talking heads start yakking.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Warning! Musings follow.

This Elvis reading got me thinking about the impersonators. Why Elvis? Why Elvis and not … [fill in the blank]. Why are there hundreds, thousands of Elvis impersonators from Malta, to Tallinn, to Montgomery? Why are they still at it now, thirty-five years after his death?

Of course there are impressionists who imitate Madonna or Brad Pitt on a TV skit. But none of those idols have the army of global impersonators that Elvis had and has. And that is the point, anyone can be imitated and many are. But why is it only the King with such an army of autogenetic impersonators? (Well, maybe not Brad Pitt since he has no personality to mimic.)

A few years ago we saw an exhibit of photographs from the early years of Elvis. The overall impression was a modest boy struggling with the demands the world was just beginning to make on him. Particularly arresting was a photograph of him walking home from the train station after his first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, a young man in blue jeans and shirt sleeves, like every other one, waving goodbye to those still on the train.

On my pilgrimage to Graceland, three things impressed me.

One was the music. It was everywhere.

The second was a video that included Elvis backstage in Los Vegas toward the end, saying ‘I am so tired’ in a voice that left no doubt that he was very tired, but the show had to go on, and off he went, in that grotesque white jump suit.

The last thing was the line of people, men and women in the shop, European and Asian, who queued up to have a photograph taken with a holograph of Elvis. Ghoulish. The King still has no rest from the rapacious appetite of the fans.

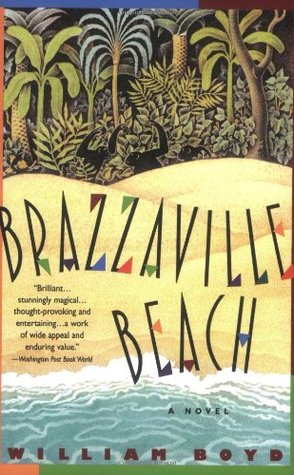

‘Brazzaville Beach’ (1990) by William Boyd

A very unusual locale and set-up for a krimi. Bravo!

The action centers on a research station in the forests along the Congo River where a multinational group of scientists observe chimpanzees sometime in the 1960s. The narrator is a recently-minted PhD who muses on what led her to this place when she is not watching the monkeys. (I do so detest backstories because they are distracting.)

The book offers intriguing soupçons about the primatological research into the social customs, practices, and habits of a clan of chimpanzees, along with a study of their diet, and movements, including bowels.

In the distance, on the far side of a mountain range there is a four-way civil (tribal) war going on, and that spectre cannot be ignored, since it might influence the funding agencies to withdraw support. Of course, there are twists and turns among the scientist, though our protagonist is so junior, she seldom sees the professional rivalries firsthand. That is, she is out in the field observing, while back in the base camp the more senior members of the party wrangle over precedence. What she sees there in the field is remarkable and in time upsets the established order.

Spoiler alert.

The book recounts three intersecting conflicts: there is war among the chimpanzees, there is conflict among the scientists over the data and its interpretation, and the tribal war mentioned above. In time, the three come together. It is all very ambitious. The first two provided more than enough material, and this reader found the intrusion of the third inevitable and unnecessary.

The most interesting aspect is the primatology. The manners and morēs of the chimpanzees in the wild, the relations among them, including the conflict that is a war in all but name. But also of interest is the relationships of the primatology observers with the chimpanzees. The scientists personify the chimpanzees with nicknames, though technically they have specimen numbers, these latter are only used in the final write-ups. Nor is there any doubt that the chimpanzees recognise and distinguish the observers from themselves and that they know one observer from another, and there is one harrowing moment when that recognition is crucial.

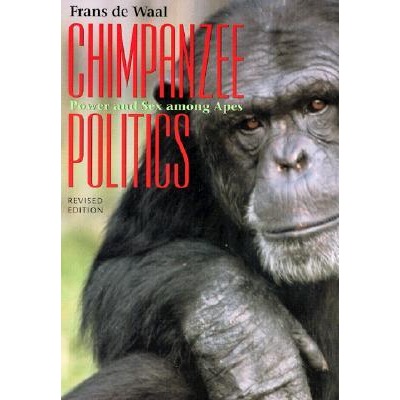

Years ago as a prospective text for the Power course, I read Frans de Waal’s ‘Chimpanzee Politics’ (1985), a study of chimpanzees in the Arnham Zoo in the Netherlands, a book that is written with panache and insight, along with a few gratuitous reference to Machiavelli that I logged in my collection of inanities about him. While de Waal’s book has much technical detail about quasi-experimental tests done in captivity, it is easy enough for a general reader, and leaves one in no doubt of the intelligence and capacity to learn of chimpanzees.

Our heroine survives it all but some others (including some of the chimpanzees) do not. She finds that among the tribal warriors are some decent folks, that the mercenaries attracted to the conflict are a varied lot, that some of the scientists on the project are unscrupulous and mercenary themselves (really?), that the chimpanzees are capable of moral acts, that her husband’s suicide which more or less drove her to Africa remains a mystery, and that…. the most important lesson, life goes on even in Brazzaville Beach.

William Boyd

William Boyd

The writing is assured; the touch is light; the themes are serious as they slowly emerge. The context is richly detailed. Altogether a good book. William Boyd has others and I might read another one day but I will not make it a priority, because I thought this one had too many themes and circumstances competing for my thin attention. Once again, I seem to be in a minority because the back cover is plastered with testimonials from the highest sources like the ’New York Times.’

The title caught my eye because Brazzaville in the Republic of the Congo was where Charles De Gaulle made his second radio broadcast, this one to the French colonies. There was a large transmitter in Brazzaville, built in the 1930s to reach the African colonies and even some air and naval traffic. De Gaulle traveled there in 1940 to win supporters, and met with some success.

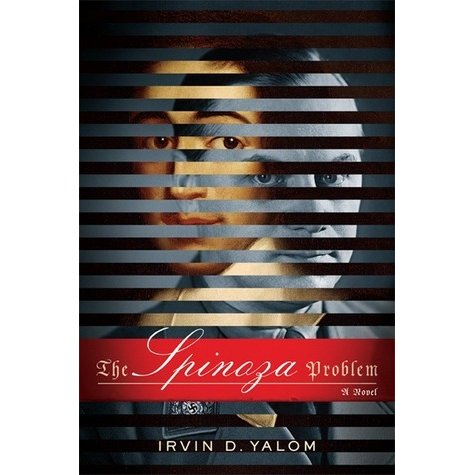

‘The Spinoza Problem: a Novel’ ( 2012) by Irvin Yalom

The setting in 17th Century Amsterdam shows assiduous research and the differentiation of characters is good, as far as I can tell. On that qualification there will be more later.

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) repays effort. The first is with his name. He was born Benedito de Espinosa of Portuguese parents who had moved overnight to Amsterdam to avoid the convert-or-die (later) Iberian Inquisition. (Why does Ted Cruz come to mind?) The parenthetical reference ‘later’ applies because even Jews who willingly converted to Catholicism were subjected to subsequent persecution. In Holland he was sometimes styled Benedict. In all those permutations his first name means ‘Blessed.’

That qualification ‘as far I can tell’ means I stopped reading the book very early. I violate my rule of the positive in this case because I wanted to express my admiration for Spinoza the thinker. In addition his reputation as a man has come down the ages as a simple, unpretentious person, whose life was a model of rectitude, in contrast to the wastrel Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the gloom-and-doom merchant Thomas Hobbes, the obnoxious self-promoter John Locke, or the nutter John Stuart Mill.

Spinoza’s two tracts, the ‘Politics’ and the ‘Ethics’ are fine books, though arid. He much admired the method of geometric reasoning. Yet somehow he is not on the starting team in the Tour of Political Theory, so I only ever managed to slip the ‘Politics’ onto the syllabus once many years ago. Ditto his fellow Dutchman Hugo de Grotius.

‘The Spinoza Problem: a Novel’ is described as a thriller, and I should have stopped there. The lure of Spinoza was, however, too much; I bought it and started to read. The book has two characteristics that I dislike so much that I gave up on Spinoza.

First, everything is written in the present tense, including flashbacks. Ergo everything is happening at once.

Second, this simultaneous action occurs across the centuries because every other chapter alternates from Spinoza’s time in the 17th Century and the 20th Century. I like my krimis linear and literal.

The early scene with the schoolboy Alfred Rosenberg (look him up, if he is unknown) getting a lesson in life at his Estonia high school is certainly interesting, and sheds some light on anti-Semitism. I wish I had been able to persist,,,, (However, there are so many other, good books that do not set my teeth on edge.)

The use of the present tense is so common I suspect it is advised by agents and perhaps required by publishers, at least, of certain genres. That is, the thriller. Why do I react to it?

When everything is happening at once, it is left to the reader to sort out sequence, to distinguish past from present, and to supply the emphasis and the pace of events, and even to supply the viewpoint. It is like looking at two-dimensional flat world without topography and without time. See, it is lazy writing making the reader do the work that the writer should have done. Stephen King would have a zinger on this. Verb tenses are tools, and should be put to work. That is why they exist.

Not everyone is bothered by ahistorical simultaneity, it seems, because the book is published by a major New York publisher and has a good rating on Good Reads, for whatever that is worth. (I never cease to marvel at the illiterate accolades heaped on some dreadful specimens. Why did Donald Trump come to mind?)

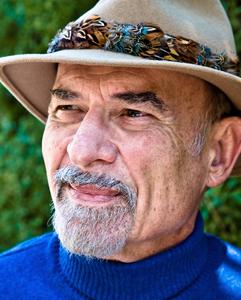

Irvin Yalom

Irvin Yalom

Confession: I was also irked by a lengthy introduction from the author about his many and deep interests. If that has to be present, put it at the back. In any event, I skipped it, something I was taught to do in college literature classes so as to make up my own mind. That I did.

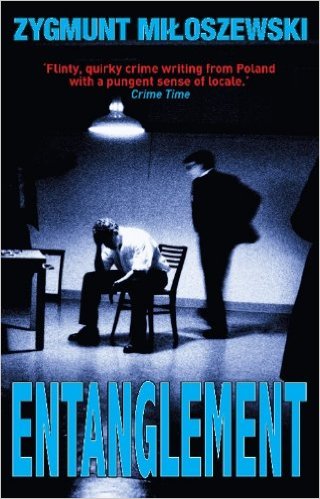

‘Entanglement’ (2010 ) by Zygmunt Miloszewski

This in a police procedural in a series following the investigations of Polish State Prosecutor Teo Szacki. In Poland, according to this novel, the prosecutor does the investigating, and not the police whose domain includes the heavy lifting and car chasing. The locale is Warsaw with its nouveau riche and old communists side by side. It is part of series.

A middle aged man in mid-career is found dead in a church, a shish-kabob skewer stuck through his eye. He was participating in a role-playing therapy group using rooms in the church. Between sessions he was murdered. Did someone take the role playing too seriously! Was there an intruder? Did the victim have an enemy who followed him there? Did he — somehow — commit suicide with that skewer?

Most of the role-playing was videoed and much of the early going is Szacki watching it with the therapist who explains the proceedings, while more than once, Szacki thinks about his own life and his own need for…something, perhaps even therapy. The theoretical explanation of the procedure seems incredible [no spoiler] but it hangs together (and adds to the mystery, which is often lacking in krimis.) In addition, the victim also recorded some of his musings on a pocket recorder, and these, when discovered, add to the incredibility of it all, because he seems at one point to be talking to a ghost.

The more Szacki digs, the more confusing and paranormal it seems to become. This mystery is not welcome to a man who lives on and for facts.

Warsaw is new to me and I enjoyed the to’ing and fro’ing around the city in the summer rain. The banter between colleagues in the prosecutor’s office, the lack of a budget for even basic tests, the vulture journalists looking for blood, the boom-and-bust all at once nature of contemporary Poland while the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, and the role-playing therapy, these are all well handled and add layers to the narrative texture.

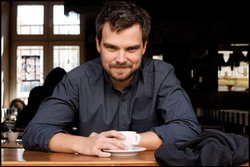

Zygmunt Miloszewski

Zygmunt Miloszewski

There is a plot wobble for this reader. Szacki seeks a second professional opinion on the therapy session and that confirms the procedure, but later…. Well, no spoiler but the curve disappointed this reader.

While the author distinguishes the characters, as always with such unfamiliar names, I found keeping the names and the individuals straight difficult. Though I consumed those dark, depressing, and dispiriting Russian novels that were de rigueur in college, I could never keep the names straight then either.

The translation and presentation on the Kindle are good. The production is far better than for the other Polish krimi I recently discussed, ‘Polychrome.’

‘Forty Days without Shadow’ (2014) by Olivier Truc

This is an Arctic krimi set in Sápmi in the far north where Finland, Sweden, and Norway converge along with Russia.

Once this area was called Lappland after its inhabitants, Lapps. It is bounded by the Barents Sea, White Sea, and Norwegian Sea. The land border is not so clear.

In winter there are forty days without sun, and this novel opens just as the sun is about to show itself again, starting with a scant glimpse of six degrees over the horizon, like a 10-watt light in the back of a freezer hidden behind something. Just the top arc shows. But when it reappears after forty days, everyone stops to watch for it.

The Sami are nomadic herders who follow and live off reindeer, borders mean nothing to either the reindeer or the Sami. The Reindeer Police Administration is, according to this novel, a response to this situation. It has multi-national jurisdiction in the Sami areas of Finland, Sweden, and Norway, but not Russia.

Our protagonists are Reindeer Police Patrol 9, consisting of a senior officer, Klemet, who is Sami and who seems to have a Swedish birth certificate, and a younger Norwegian woman, Nina. They ride around on snowmobiles keeping an eye on the herds and the herders to prevent disputes among the herders and between them and other locals, though there are few of these. Klemet broods a lot.

A very exotic location with lots about the place, the weather, the aurora borealis, different kinds of ice, the past, the tensions, including some left over from the Cold War with the biggest home to Sami, Russia.

A pathetic Sami reindeer herder is murdered and at the same time a Sami artefact at a local museum is stolen. Are the two events connected. and if so how? Some of the locals think the only good Sami is a dead one, and say so. Moreover, the local police have little interest in Reindeer Police Patrol 9. Nor do the real Norwegians, real Swedes, or real Finns care about the murder of a Sami alcoholic out on the tundra, nor about any useless artefact, viewing the Sami as a nuisance or hinderance.

But in the course of sorting out the aftermath concerning the victim’s reindeer our protagonists see connections between the murder and the theft. The plot is clever and the place is compelling. Klemet is rather too self-absorbed for me, but he does snap out of it occasionally. The most arresting character is the firecracker who is head of the Nordic Geological Institute who becomes involved. The most formidable is the Sami herder Aslak who lives the old way and seems almost to be a part of land itself. The author distinguishes effectively amongst quite a cast of characters.

I liked the way the Sami culture plays into the mystery with the artefact but also in other ways. Klemet’s uncle with his girlfriend prove what a small world it is.

I wondered about language barriers. Kelmet speaks Swedish. Nina is Norwegian. According to Wikipedia the Sami peoples have many languages. The locals are mostly Norwegians, but there are some Finns and even a Russian or two.

Olivier Truc

Olivier Truc

It is translated from French, which surprised me given the intensity and variety of local knowledge on display I had assumed the author would be of that place and write in one of the languages of that place.

Joanna Jodelka, ‘Polychrome’ (2013)

An elderly man in Pozan Poland is found murdered. The more closely the investigating officer, Mariej Bartol, examines the scene the odder it looks. The victim is posed, naked, and almost seems to be smiling despite the strangulation. Then there are the Latin mottoes found on the flower vase, inside the bow of a pair of glasses. Enough to set one to thinking.

Then a second man is found, also posed, also with a few Latin mottoes discretely tucked around the scene.

We get quite a bit of the personal life of our hero, and his mother is some character. But it is laid on with a sledge hammer.

Our hero seems to have been born dumb and misses the obvious a few times.

On the other hand the officers he works with are well drawn, and there is much to’ing and fro’ing in and around Poznan in a wet spring. It has some sense of place.

Then there is the Latin scholar he recruits through his mother’s contacts to make sense of the tags. She is a firecracker from go to whoa, and our hero suffers a rush to blood to his first friend, making him even more slow-witted than usual.

I read it on the Kindle and it was not easy. There were odd font characters, broken lines, run-on paragraphs, spelling errors, and more. The translator into English seems to be a Pole, and I guess that explains the syntax errors and the unfathomable idioms which may make sense in Polish but do not in English. Maybe the translator once worked for Jimmie Carter. (Either you get it, or you don’t.)

Joanna Jodelka

Joanna Jodelka

Before trying another one of these I would want some reassurance that editorial improvements had been made. On Amazon the paperback is $0.08 which is less than the Kindle version. Not sure what to make of that.

It is a double whammy, a lousy presentation and badly translated. It was too much like reading student essays. There were students of my acquaintance who thought that if the work they submitted was incomprehensible, then the instructor — moi — could not fail it. WRONG! They would then challenge me on the ground that their paper was…, yes, incomprehensible, and since I did not therefore comprehend it, I could not honestly fail it. Imagine the time I spend in such conversations. Now it is easy to see why retirement has its attractions.

For what is worth and to balance the books, I had more than one similar conversation with a Ph.D.-bearing lecturers who asserted, no evidence required, that their lousy teaching stimulated students to learn for themselves. This was no argument about the meaning of lousy teaching, they admitted it and celebrated it. Needless to say these individuals all prospered. What did I say about retirement?

The Bette Davis Club (2015) by Jane Lotter.

Or, Margo’s adventures through the money glass. Reluctantly, Margo goes to the wedding of her niece, and the fun begins in Hollywood. The spoiled bride bolts, and the vampire mother of the bride makes Margo an offer she of near bankruptcy cannot refuse and a black AMEX card! She throws in the keys to a red MG and the groom! Who knew such cards existed? Not us plebs.

Off they go down Route 66 meeting all kinds of people, some of the most memorable at the Lesbian dance contest in Palm Springs, others with whom they exchange insults over breakfast, a kindly woman who presses a marriage manual on Margo, and Boone who seems destined to be in recovery from head injuries. He should have stuck to football.

Cary Grant even puts in a cameo appearance,. This book has it all, and more!

Finding the bride, after all this, is anti-climatic. She is a brat.

Margo’s confession at the meeting set a new standard. Indeed. No spoiler here. Find out for yourself.

Along the way the imbecilic nature both of Hollywood and its audiences are noted.

Margo is wrong about almost everything but soldiers on. She may be broke but it is not from a lack of effort.

It shifts gears from silly to serious and back several times but the mix is well judged.

Jane Lotter

Jane Lotter

I was very disappointed to learn it is a once-off.

Ian Samson, Death in Devon (2015)

This krimi is a light-hearted romp through distant Devon. This book is second in series not first. My mistake.

Our hero, Sefton, is amanuensis to Morley, an H. G. Wells-type, in 1938. The know-it-all Morley is author of endless titles including a series on English counties. Nice set up.

They fetch up at a school where Morley has been invited by an old friend to give a lecture, and there they find strange doings. Alex, the handsome and confident head teacher, has a plausible explanation for everything, but, still, Sefton has doubts. He also is jealous of Alex’s designs on Miriam, Morley’s daughter, who drives the Lagonda on these excursions. She, for her part, seems to welcome these designs.

There is a death, claimed to be an accident, of one of the school boys. Animals disappear from a nearby farm. Strange noises in the night are reported.

Sefton is, of course, right, and for all his blather Morley is quick thinking and acting in the crisis.

That makes it sound better than it reads, I confess. Many, very many, altogether too many of the pages of the first two-thirds of the book are given over to Morley expatiating on endless, irrelevant subjects. Exhausting. Pointless. Did I say, tiresome. Morely is an expert on everything and has to prove it minute-by-minute.

At the outset I compared him to H.G. Wells because of that know-it-allness, and the endless list of his book titles, but he is not as pompous and self-important as I suppose Wells was. I say that because I suppose some of Wells’s book have an autobiographical element, e.g., ‘The New Machiavelli.’

The three principals are likeable, the set up is clever, and the place, Devon is different. There is some mis-direction about those caves that keeps the suspense alive. But Morley droning on, while Sefton mentally footnotes the drone to his list of publications, is deadening.

Ian Sansom

Ian Sansom

Loved his bad books library series set in Northern Ireland.

Martin Limón, ‘The Joy Brigade’ (2013)

This is the eighth title in the adventures of George Sueño and Ernie Bascom, Crime Investigators, Military Police, United States Eighth Army, South Korea in the 1970s when the Cold War was often very hot. Sueño is the thinker of the two, while Bascom resolves most problems with his fists and sometimes with an illegal hand gun.

Having read the previous seven titles over a number of years, I had noticed that North Korea never figures in the books. The villains are inevitably Americans and South Koreans in some combination. Not so in this title. The setting is North Korea.

Sueño has agreed, for reasons of his own but as always involving his first friend, to go into North Korea undercover. Whoa! How can this 6’ 2” American G.I. go undercover in North Korea! Limón contrives some pretty clever ways and means to explain that. They hinge on (1) the isolation of North Korea and North Koreans from the wider world and (2) the tyrannical nature of the regime.

Because North Korea is so isolated, North Koreans, even North Korean police, reason from the propaganda stereotypes the regime has drummed into them for thirty years at the time of the story. Americans are blond-haired and blue eyed with enormous noses. Sueño is a Latino, big, yes, but dark with a cute little nose.

In this tyranny every mistake and failure is greeted by maximum punishment. Not only will the erring official be executed but so will be two generations of his family, his parents and likely his in-laws as well as his own children. This terrible possibility is around the corner for anyone. Just read the news today to realise that is still the practice. Consequently, no one reports anything if it can be avoided, because there might be a mistake. The best way to avoid mistakes is to do nothing. Sueño trades on this reluctance to admit trouble.

He has some tenuous contacts in the North who, also for reasons of their own, cooperate. That standard trope is vividly realised in the case of Kang, but credulity is stretched. Kang gets away with too much and is too conspicuous for the suspension of disbelief. He leaves a trail behind him even Dr. Watson as played by Nigel Bruce could follow but no one is able to follow it. Go figure.

Now inaction may be the safest course, but safety is not guaranteed so the North Korean black market offers a service to officials who realise something is wrong but do not wish to report it through channels. They can hire unofficial fixers who will solve the problem for them without leaving a trail. These fixers are often police officers moonlighting, and in these unofficial investigations they are even less constrained than they would ordinarily be though they, too, have to be careful to cover their tracks from their own superiors, usually by splitting the profits and glory.

The portrayal of North Korea in the book is, to say the least, Orwellian. There is the chanting of slogans of praise to the Dear Leader. There is the robotic obedience to imbecilic commands. There is the starvation of most people amid the lavish luxury of the elite. It is enough to satisfy even Ted Cruz.

Kim Il-sung

Kim Il-sung

Sueño’s cover is that he is a Peruvian sailor with the papers to prove it working on an Albanian ship distributing and collecting cargo along the west coast of North Korea.

That he understands and speaks Korean from long study during his many years in South Korea gives him a double advantage. The first advantage is that he understands what he hears and reads. This advantage is multiplied by the second advantage which is that no North Korea can believe a foreigner understands, still less, speaks Korean. They have been told for so long how unique and special North Korea is, and how barbaric and backward the rest of the world is, that a foreigner is barely human in the eyes of most. In his private moments Sueño compares that attitude to the disdain Anglos showed him when he grew up Latino in East Los Angeles in the late 1960s. It is the same at bottom but it is magnified a thousand times in North Korean.

The plot is, well, fictional. Spoiler alert! The conceit is that a division the North Korean army wants to overthrow the Government of Dear Leader but needs the help of the US 8th Army to do so. Sueño is supposed to convince the 8th Army to hand over fuel, medicines, food, ammunition, and weapons to this division to enable it to do so. Huh! A sergeant is going to convince the 8th Army Command to risk starting a war by violating the DMZ, and in so doing will tell the South Koreans what? Pointless from the get-go.

I have not mentioned the action man Bascom because he did not figure in this book, and I find that is something of relief. In the last title or two I have read in this series I found Bascom’s adolescent temper and libido getting on my nerves.

As always with these books, the place and period are superbly rendered. There are no jarring anachronisms or cultural slips. The characters are each distinguished by speech and attitude, as well as appearance. There is no pointless description of clothes, rooms, or food that pad out so many tedious krimis.

Martin Limón

Martin Limón

When I taught a semester at Korea University in 2004 the director of the Korean Studies Department told me that a reunification of the Koreas was inevitable and would be catastrophic for all concerned. He meant that it would happen one day, and when that day came no one would be able to moderate, slow, temper, channel. or resist it. He also meant that the regime in the North was fragile and could shatter at any time, probably due to starvation. Finally, he meant that the people in the North were creatures of the regime in a way that East Germans were never creatures of the DDR. This last is the most interesting and telling point.

The isolation of North Korea has been much more complete and effective than that of East Germany. East Germans were exposed to radio and television, first from other Warsaw Pact countries and through them to even more sources. In East Berlin they could literally look into the Western World. There was also exposure at a personal level in East Germany through visiting tourists from the West as well as other Soviet Allies. Most East Germans could get West German television programs at home if they dared to adjust their sets. And so on. There were many cracks in the walls around East Germany. Not so North Korea.

The jamming of radio and television and the language barrier to Chinese and Japanese precludes the taint of the airwaves. The kind of punishments dished out routinely in North Korea would discourage anyone from adjusting a television set, not that anyone in North Korea owns one. That is the most important insulator, the poverty and ignorance that the population is kept in. Foreign languages are not taught in part to block contact with foreign ideas and practices. They know nothing of the rest of the world but what the regime says.

Integrating the two Koreas would be far more difficult than integrating the two Germanies. The North Korean regime would have many diehard loyalists, and not just from the elite, who would not readily forsake it. There would be no comparable flood of North Koreans willingly leaving North Korea for the South as East Germans flooded from East Germany to West Germany overnight.

The North Korean regime might collapse due to starvation or a palace coup but then nothing might happen, no one would move. The pressure on South Korea to act would be great, largely from its own population but if South Korea entered the North, even bearing food, there might be armed, if disorganised resistance…. a grim picture, the more so when nuclear weapons are available.