The first in the series.

Alex Delaware is a psychologist who is gradually drawn into police work when a child abuser commits suicide in his office during the night. Delaware had been working with the victims of this perpetrator. That event jarred Delaware loose from his profession, his clients, his positions, his habits and much else. At the same time it also opened the door to helping the police with inquiries, in that quaint British expression.

In this case, a fellow psychologist has been murdered along with his girlfriend, and while Delaware did not know the man personally, there is a professional interest and then a police officer asks for his assistance in questioning a seven-year old child who is the only witness to event in an apartment complex in Los Angeles. ‘Questioning,’ as we learn, is not the right word, but rather finding out what the child, now very frightened, saw and then interpreting that. The child arouses his sympathies and he is hooked. If it sounds rather contrived, it is not in the reading.

I particularly liked his long interview with the curmudgeonly emeritus professor who enjoys dishing the dirt. If only…. The description of the rainstorm charged by lightning was very fine, though by then I was impatient to get to the point.

The killing of the dog was too much. Every woman Alex meets is attractive and attracted to him, but he manfully remains loyal to Robin. Tedious.

All of the pieces do fit together in the plot, though it is far-fetched, but then again maybe not. Reality is sometimes hard to believe, too.

There are thirty or so Alex Delaware krimies that I have never read, despite my taste for police procedurals. It came to mind when I recently heard a Garrison Keillor ‘The Writer’s Almanac’ podcast in which he mentioned Kellerman’s long road to publication. Ten years of typing away three hours a night in an unheated garage in New York and stacks of rejections before the first publication.

By the way, this is my third Kindle book reading.

Category: Krimi

‘Henry Wood Detective Agency’ (2013) by Brian Meeks

The first in a series of self-styled noir mysteries set in January 1951 in the Big Apple. A very easy read with many short chapters and some interesting characters, and then there is that closet which, like Henry, I thought was going to be explained and wasn’t. I kind of liked that. There was also plenty of woodworking.

It is at once very conventional and somewhat unconventional. The tough cop. The honourable criminal. The femmes fatales, who turn out to be OK. But mostly it is connect the dots. There are some bons mots but it does not crackle.

There is no tension and the characterisation is left to the woodwork. Too many chapters started with a new character who proved to be ephemeral anyway.

The rapprochement between the food critique who has an office nearby (and not at the newspaper for some reason) and the tough cop is not convincing, not interesting, and not relevant. They will probably appear in later titles in the series.

The mystery is that closet where occasionally Henry finds gifts from the future for both his hobby of woodworking and his job of detecting. That and Bobbie the motor-mouth estate agent who seems to know Henry’s business better than he should.

Brian D. Meeks

Brian D. Meeks

Left me unsure if I want to read another one in the series.

I read it as a Kindle book. My second.

‘Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders’ (2012) by Gyles Brandreth

The fifth in the series and better than ever. Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle were friends, and the premise of this series is that Wilde is the model and inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, with his encyclopaedic knowledge, instant perception of facts, computer like processing of information, grasp of new languages in minutes, bolt holes here there and everywhere, mastery of disguise…

In this entry, Wilde and Doyle travel to Europe, each to escape his adoring fans, for some R and R. But no sooner do they check into a hotel than the game is afoot.

Doyle receives some strange mail, forwarded by his publisher, addressed to Sherlock Holmes. That has happened before, but not like this! Doyle shows and tells Wilde, and Oscar insists that they follow-up.

Toute Suite the trail leads to Rome and to the heart of Rome in the Vatican. Once in the eternal city, Doyle takes things as a they seem to be, but not Oscar who sees mystery and deceit in the very air. Some of the scenes occur under the dome of St. Peter in the dead of night.

Gyles Brandreth

Gyles Brandreth

The period details, the travelogue, the dialogues, but most of all the stolid Doyle as Waston to Wilde’s mercurial Holmes is a great fun.

‘Something Bitter on the Princes’ Islands’ (2008) by Lawrence Goodman

‘An Istanbul Mystery’ says the subtitle, the fourth in a series, but the only one readily available to me.

A nice set-up with the young girl exploring the island while the dog takes charge. There is a mystery in a cave and an array of characters, Cousin Evangeline and Uncle Orville added to the mayhem. The séance was a laugh. The running joke about the talking dog was deft. The plaintiff ney lessons were part of the local color.

It is amusing, and the children are fun, and the final denouement surprised me.

On the other hand the French diplomat was not even cardboard, and after he was inflicted upon the reader, he was then dropped. Likewise the two French police officers, who were portrayed more kindly, were introduced and then dropped.

Laurence Goodman, from the back cover

Laurence Goodman, from the back cover

Having said that, I am not motivated to seek out the other titles in the series.

‘Groucho Marx, Master Detective’ (1998) by Robert Goulart.

After seeing ‘Duck Soup’ (1933) I had Groucho on the brain. Then I remembered this book which I had started to read years ago, but it had gotten bumped by…a deadline, another book, a failure of concentration, the winds of time, or something. My flawless shelving system allowed me to retrieve in a the twirl of a moustache end.

It is simple and diverting, though Groucho wears, erodes, irks, and bores. Julius Henry Marx just does not have an off-switch. Even when sleuthing, he is wisecracking and pratfalling much to the irritation of his straight-man Watson, Frank Denby, a gagwriter for radio when not sleuthing.

In 1937 a girl’s suicide in Hollywood irks Julius who is quite sure that she was not the suicide-type, and Denby finds the police stonewall suspicious. Off they go…. A midnight visit to a funeral home /office /parlour is straight out of a Marx Brothers picture with an unexpected touch that I will not spoil here.

They come up with nothing but then, true to the scriptwriter’s formula, someone takes a shot at them, convincing them that there is a conspiracy afoot. The plot twist toward the end was visible for miles.

There are a number of other titles in this series from the industrious Mr. Goulart.

But if the trash-talk of Groucho was cut from this book, the remainder would be a short story of 60 pages or so. Too bad because the writer can write. The romance between Jane and Frank is charming, and some of the minor characters like the aged bellboy are well drawn, and the plot brings in the usual suspects, crooked cops from Bay City (where else), gamblers, starlets who will do anything with anybody for shot at fame and fortune, and even a bloodhound.

Wikipedia is full of information about the Marxes. The short version is five brothers, one of whom never acted, Gummo, another, Zeppo, who only did a little before moving on, and the three core brothers of stage, radio, and screen: Groucho, Harpo, and Chico. Stage names, yes, all ending in ‘o’ as was some fashion in their early years. Even Gummo who never took to the stage had an ‘o’ nickname to be consistent.

From left to right: [do it yourself]

From left to right: [do it yourself]

Chico because he chased women (chicks), Harpo because…. [figure it out]. Zeppo after the airship. Gummo because he crept around like a gumshoe. And Grocho because…. He preserved his mystique by giving numerous explanations over the years. Their parents immigrated to New York from Alsace, ethnic German Jews. No relation to Karl, the one without any sense of humour.

‘A Title to Murder: The Carhenge Mystery, a Western Story’ (2004) by James C. Work

I came across this title in March 2015 on a list of krimies set in Nebraska provided by the Omaha Public Library. When my eye fell on it, I knew I had to read it. Amazon came to the rescue with a copy. Carhenge! Been there, see that! Once you’ve seen Carhenge, it stays. We have tried for years to work Carhenge into conversations with the globetrotters we meet. Paris, Rio, Shanghai, Cairo, New York, these have little to offer in comparison. [Applause!]

The setting is college summer school offered in Alliance (named by French trappers having taken a wrong turn from the Platte River, they were a long way from anything to trap)— class lists (inaccurate), class rooms (unready), dean (officious), photocopying machine (broken down), internet (off line), textbooks (not arrived), desk top computer for the visitor (inoperative), one pushy student (give me the syllabus now, four months before the session starts!), and more slack students (going through the motions for career or social purposes). In short, a typical summer school. The only thing I found hard to believe was a full professor from the University of Colorado had a modest mien and accepted this assignment and seemed to like students and teaching. That is not a creature I have caught sight of in our local zoo.

These students are largely elementary school teachers accumulating credits either for another degree or to comply with a continuing education requirement. That, too, is familiar. Inevitably one student comes late to the course and another to each class and both demand to know what has been missed (i.e., private tuition). Another underlines every word in the reading but cannot answer any question about it (trees without a forest in sight). Par for any course.

One of the students disappears from class. Yes, that happens. But a few days later her boyfriend is found with a very big knife stuck in his very dead body…. Everything indicates she did it. Now that is not par for any course.

Moreover, she was a thoughtful and bright student who had befriended (advised and counselled, he discovers) several of the other women students. Could she be the culprit?

David McIntyre, our hero, wonders about this and he meets a few local people who, knowing her better than he does, also wonder. The pace is deliberate, and the passing parade of small town characters is given its due. The freelance mechanic, a weedy, bony, twenty year old with tattoos and studs, who longs to be a tough guy but keeps tripping over things, he is a hoot. The denizens of the burger joint act as a Greek chorus. Then there is the heat in the panhandle – open spaces are no-go zones after 10.30 on a July morning. The canopy of elm trees captures and holds a stifling, albeit shady, heat beneath, dark and hot like an oven. Most of all, there is: Carhenge.

The book gives instructions on the best method of viewing the site. To find that out, read the book for I shall not reveal it here. I hope to visit Carhenge again myself next year and make use of the instructions I found here.

James Work

James Work

That the plot turns on several novels is great fun and very well realised. There are other literary krimies but none quite like this where life is art is life. Readers of the book will follow. Readers of ‘Tess of the d’Urbervilles’ will put 2 and 2 together and get Carhenge.

If Carhenge is unknown, add a brick to the wall of knowledge by reading about it on Wikipedia, or see the film! [Yes, Mr. Spock, there is a film.] Best of all, pay it a visit.

Martin Limón, ‘The Wandering Ghost’ (2007)

An early entry in the long running series of the cases of sergeants Ernie Bascom and George Sueño, two investigators in the United States 8th Army in South Korea in the middle 1970s. The Cold War is intense and no where more intense than along the Military Demarcation Line within the Demilitarized Zone. South Korea has a military government that justifies its crimes as necessary for security. American conscripts discover that money can be made in the black market, selling U.S. army equipment and supplies to Koreans. There is plenty to go around, unless someone gets greedy. Well, yes, that does happen.

The time and place are richly detailed. including the ways of Korean National Police and the interstices of the U.S. Army. The 8th Army wants no trouble, preferring to ignore corruption and even murder within its ranks rather than face bad publicity. The investigation of the death PFC Marvin Druwood was superficial and the subsequent disappearance of MP Jill Matthewson is even less thorough. No sooner is the carpet replaced on these two events, then Bascom and Sueño arrive.

Jill’s mother had written to her congressman who in turn has insisted on answers. To go through the motions Bascon and Sueño are sent to the Second Division near the DMZ with a very limited remit. The Second is a field unit while our protagonists are Rear Echelon M…. F…..s; they are not welcome and the veneer of cooperation drops quickly. No one is happy about the assignment. But of course, once engaged Bascom and Sueño just will not let go.

Bascom is the action man. Show him a door and he kicks it in. A roomful of thugs delights him and only Sueño can hold him back, most of the time. Volatile! He has a self-destructive fearlessness that frightens Sueño at times. For his part Sueño is the strong silent type who spends all his spare time learning the Korean language and culture. Life is a puzzle to him and tries to figure it out. Bascom is on a one-way ticket and determined to enjoy the ride, while Sueño cannot quit an unfinished job. Bascom is often impatient with Sueño’s efforts to figure things out, and he neither understands nor cares about the explanations Sueño produces.

They are both cast-iron in these pages. They drink enough alcohol to kill a normal man and seldom sleep more than four (4) hours a night on the case, while travelling the length and breadth of South Korea in an open jeep in the winter! After several beatings, it takes each of then a few pages to recover. Ironmen, indeed.

Limón draws his Korean characters with respect, none are plot devices. The prostitutes are business girls, proprietors of their own small business. The bars and brothels supply the American demand which has created much that is ugly in Korea, but nonetheless the Northern threat is very real. There are martinets among the army men they encounter but there are also some very wise owls who have survived a long time in troubled waters from whom a nod or a hint goes a long way. Sueño has learned to read these signs, which largely escape Bascom.

Martin Limón, whose affection for Korea shines through.

Martin Limón, whose affection for Korea shines through.

The books are more violent than my usual fare but the compensations are in the travelogue and the puzzles in the plot. In this title I also warmed to the idea that the ultimate prize was a celadon crane vase, perhaps like some we saw at the national museum in Seoul in 2004, and not money or drugs. I do find Bascom’s hormones repetitive.

In a world of misnomers, the Demilitarised Zone must take some prize. It is completely militarised. I visited the DMZ twice in 2004 and found it scary. A million or more men armed to teeth are each side of a line down the middle of a meandering river. Yikes!

‘The Case of the Love Commandos’ (2013) by Tarquin Hall

Vish Puri, India’s greatest private eye, as he finds occasion to remark several times in these pages, is on the case with his redoubtable team: Doorstop, Facecream, Tubelight, and Grunt. With such an ensemble cast, what could go wrong? There is a lot of trip and some arrival, too. The trip includes a selection of Indian cuisine became Puri is always hungry, and always eating. The back-matter of the book includes several recipes and a glossary of Indian terms, many of them are food.

In addition to Puri’s team of operatives there is his arch rival Hari Kumar and Mummy, Puri’s inquisitive. intrepid, and tenacious mother-in-law. And then there are the Love Commandos.

When Romeo met Juliet neither set of parents was happy and between the loving couple placed many barriers, yes? We all know how that story came to a sad end. They needed the Love Commandos to extract them from their parental restraints and spirit them away to a new life together. In an India with arranged marriages there are many Romeos and Juliets and the Love Commandos fill a market niche by offering elopement services for just such couples.

Puri is a traditionalist in every way including arranged marriage which has worked out fine for him. But his number one operative, Facecream, it turns out, moonlights as a Love Commando. Disapprove though he might, she has always been a loyal and adept agent and he can only return her loyalty by assisting in one of her commando operations when it turns bad.

From Dehli to Lucknow with a side trip to Agra, the adventure unfolds, while Puri eats his way through some of the regional cuisines of India but one step ahead of his rival Hari Kumar, who for reasons to be revealed later, seems to be working the same case. Corrupt politicians, unscrupulous Swedish medical researchers, retired Gurkhas hired out as muscle, an unholy holy man, some miserable Dalits (Untouchables) are among the parade of characters.

Tarquin Hall

Tarquin Hall

The touch is light and the book is replete with slices of India but the plot is deadly serious.

I have read two earlier titles in this series with equal amusement and enlightenment.

Black Bird by Michel Basilières (2004)

Genre? Novel. Style? Northern Gothic, certainly. Magic Realism, maybe. Rating? * * * *

What happens in it? It is a circus of characters and incident. Part satire and part hyperrealism.

In her one-woman struggle to free Québec from the evil Anglos young Marie inadvertently blows up her maternal grandfather who becomes a spectral observer thereafter.

The Francophone police officer shown is trying to defuse an FLQ bomb. It blew up and left him maimed and crippled.

The Francophone police officer shown is trying to defuse an FLQ bomb. It blew up and left him maimed and crippled.

Her feckless twin brother Jean-Baptiste is irritated that with his own name in Montréal he cannot read French. The crow that Aline keeps in the kitchen attacks Grandfather. Tabernac! The FLQ consists mostly of spies in the pay of the Gendarmarie Royal.

Grandfather before and after losing the eye pursues his profession with father. They are grave robbers and Mont Royal is their hunting, well, digging, ground. They are accustomed to finding others, living there and work around them. But once the ground freezes in November, they have to wait…or do they?

In a ramshackle, decaying house three or is it four generations of Desouches live. Grandfather, father, and uncle, as our narrator terms them, shun the company of neighbours. This is another uncle apart from the one who was passing the letter box when Marie’s bomb went off, heralding a new era of freedom for Québecois. Then there is mother and Aline. I found it hard to keep the family straight. I started to make a score card, but that slowed down the reading, so I stopped. Pace is everything in these pages.

Father does not join the grave robbers, preferring instead to do nothing at all. He is surprisingly energetic in this pursuit.

Basilières includes the FLQ Crisis and the War Measures Act with René Lévesque’s manslaughter, the murder of Pierre La Porte with his own crucifix. Salutary reminders for those who find Canadian politics boring that boring is good compared to the alternative. The Montréal Basilières’s conjures from his keyboard lacks only voodoo and Spanish moss to be a cold version of mysterious and eerie New Orleans found so often in the popular culture in Southern gothic novels.

The Christmas gifts Jean Bapiste and Marie exchange in their mutual incomprehension are treasures. He only knows and relates to books but he is dimly aware of Marie’s activities. Ergo he gives her a copy of Carlos Marighella’s 1969 ‘Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla.’ She supposes he means it as a condemnation of her feeble efforts, and flies into a rage. But not before she gives him a blank book to show her contempt for his reading and writing, and he takes it to mean she wants him to write in the book and he immediately sets to to work to do it and indeed does. (It is a blank note book bound to look like a book. Their misunderstanding is complete and to the core.)

The subsequent account of the performance of the play that emerges from the blank book is a wonderful satire on everything it touches from the producer-director to the audiences. Nothing is sacred. Calice!

Fact is one thing and fiction is another and this is fiction: This is a Montréal populated by grave robbers who siphon off the neighbour’s natural gas to heat their ark but cannot control it so that house is an oven during the coldest winter, a Montréal where Felquiste and Pequiste hate each other and no one but them cares one whit and that drives each of them to new heights of frustration, a Montréal where a glass eye offers better sight that the real thing, a Montréal where the timeline of history bends….

It is no accident that the family physician is named Dr. Hyde who is a famous surgeon and yet is ready and willing to make house-calls to the Desouches (because they supply what he demands – see above). The good doctor does his most important work alone at night, and has some unexpected success.

Michel Basilieres

Michel Basilieres

Marie becomes an avenging angel and single-handedly kidnaps the British Trade Commissioner and later she strangles him to death with his own rosary chain. It is Rated-R and rather gruesome, and she, of course, finds it difficult to do and to live with, but…. Then there is that lousy gas connections, and boom, many problems are obliterated. Marie, in another time and place, would have been a postulant in a convent such as imagined in Ron Hansen’s fine novel ‘Mariette in Ecstasy’ (1991), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

One of the most exhilarating novels I have read. I came across it in a Montréal bookstore while walking some of the streets described in it and that added a frisson the first time I read it in in 2009. It came to mind recently as I read a few things about Canada and Québec so I sat down with it again. Great fun. Gabrielle Roy chronicled Montréal life in a series of wonderful novels in the 1940s and 1950s. Wry, gentle, bemused and serious, they are. In this book, by contrast, nothing is serious nor sacred. Though it is deeply ‘de vieille souche’ as they used to say on that island in the fleuve St Laurent, it was written in English. Those among the Québeceratti who take themselves ever so seriously avoided any mention of the book. The contemporary reviews I found were all in English in English-language publications. One of which chides the author for mashing together the FLQ crisis and the PQ government and confusing Pierre LaPorte with James Cross. Not everyone gets the point, it seems.

Raymond Chandler, The Long Good-bye (1954)

After reading Benjamin Black’s continuation of this title in ‘The Black-eyed Blonde’ this old favourite was on my mind when I saw it on the shelf of the Megalong Bookstore in Leura.

This is Chandler’s last complete novel and it is twice as long as any of his previous ones. Indeed it was very long for the genre when it was published. I thought I would read a chapter or two before bed the other night and found myself on page 100 at midnight, such was the flow of characters and events. Another four nights and I was done. Of course, I had read it before and then Black’s book had refreshed some of the characters for me.

Beginners can start here. Philipp Marlowe meets an odd character, one Terry Lennox, whom he gets to like and sees now and then over several months. Very early one morning Lennox appears and asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, no questions asked. Marlowe agrees, opening the can of worms that wriggle out over the next 400+ pages.

Once again Chandler proves expert at pace and development. It moves but the reader can follow, and as it moves the characters and situations are fleshed out. If he describes the clothing a character wears it is because it reveals a social situation, an attitude, the money, something about the person that comes into the story. No description is an end-in-itself in Chandler; it serves a larger purpose, or it is omitted. Scores of contemporary writers should learn that lesson.

And he differentiates characters one from the other, even if the appearance is fleeting. The jailer who opens the door to the cell where Marlowe will sit and ponder friendship for three nights says nothing, but he is etched in his posture, his walk, his silent appraisal of Marlowe. Nothing is said between them but they understand one another: Marlowe will make no trouble and the jailer will leave him alone. The tough talking newspaper man is a stock character, yes, but this one is just a little bit different, an individual, neither a stereotype nor a plot device. The cab driver who declines the tip has his reasons. The several police officers are each individuals, some very unpleasant, some vacuous, and some well-meaning but exhausted, all different one from the others. Then there is the New York publisher who tries to do the right thing but cannot quite see what that is.

Another lesson for today. Too many, far too many krimies that I try to read now present a parade of characters who all effect the same speech patterns even when they ostensibly represent a variety of backgrounds because, I guess, the authors cannot control the language, or worse, do not perceive the similarities. Neither is a recommendation.

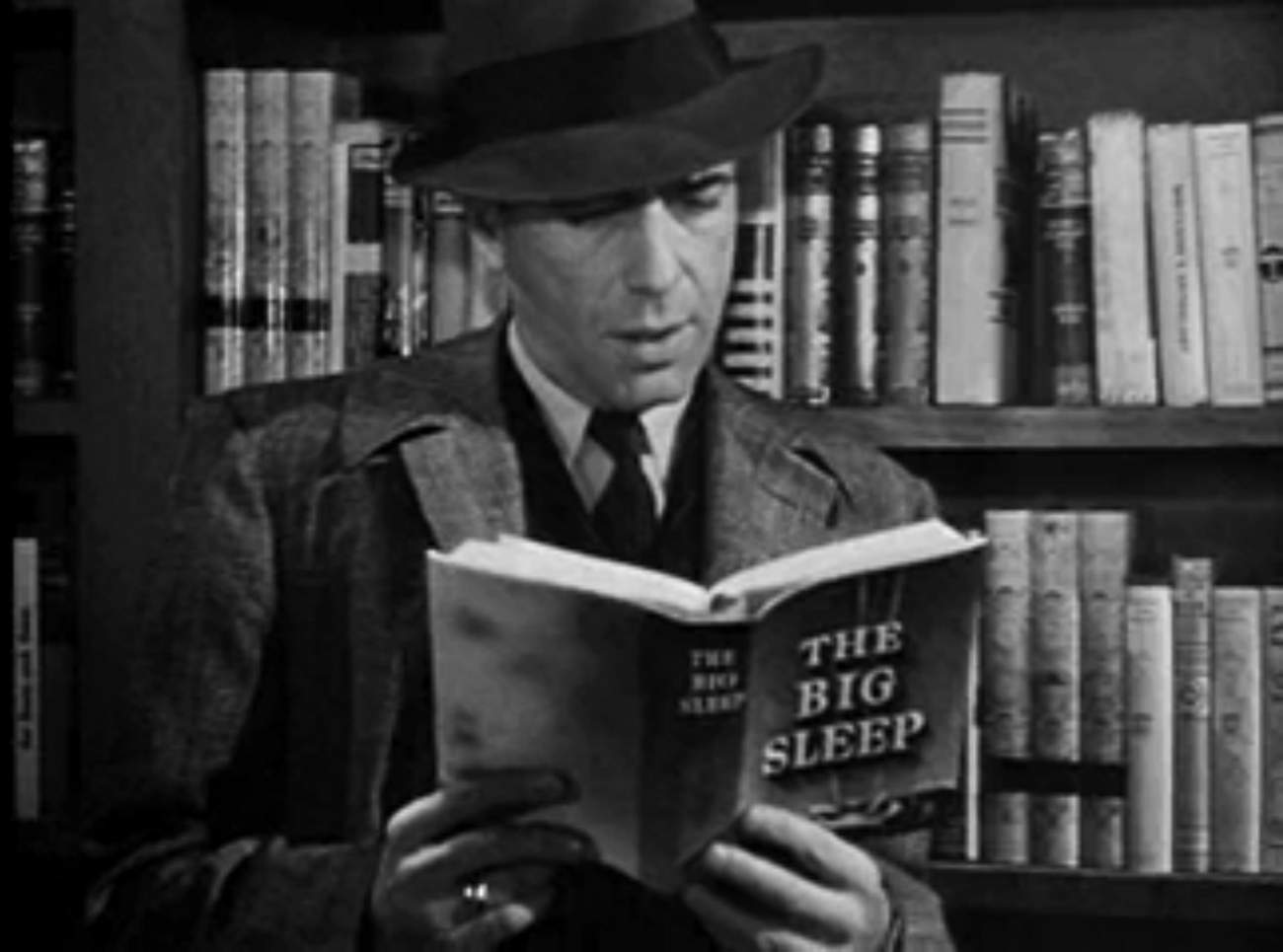

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Bogart reading Chandler on the set of The Big Sleep, as a publicity shot.

Then of course there is Eillen Wade, or as Marlowe calls her: The Dream. The page crackles when she walks in. That one man in the room does not look at her is a sure sign to Marlowe that he is up to something.

In the six Marlowe titles we learn almost nothing about Marlowe but here, when quizzed, he says a few things about himself: born Santa Rosa, parents dead, only child, played football once…to explain some crooked teeth. So much for the backstory in a half a dozen lines. Chandler’s focus is always on the here and now. This focus keeps the story moving and also preserves Marlowe’s mystique. Contrast this spare account with the verbose backstories that derail the action, if there is any, in so many contemporary krimies. I read one recently that interrupted the action with a 100-page backstory about the protagonist, at which point I quit reading it. (No this back story did not tie into the story, of that I am sure.) It was like listening to the drunk in a bar who wants to tell whoever is there his own fascinating life story. No thanks.

If Chandler’s prose is economical, decisive, and penetrating, the dialogue is even better. Chandler had an ear for the spoken word. If the descriptions single out individuals, their talk clinches it. Superb.

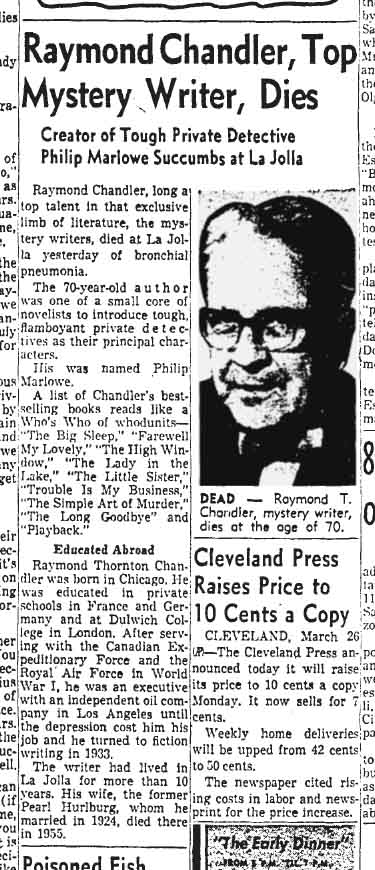

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

One obituary of Raymond Chandler.

I have read this novel at least once, perhaps twice before, and I had a very strong recollection of one of the minor characters, Earl Wild, at the ranch. I anticipated his appearance and he did not let me down, but I was surprised, given the memory I had of him, how brief is his appearance on the page. Very brief. Likewise, I remembered though not as vividly the T. S. Eliot quoting chauffeur Amos in the last few pages, Chandler’s riff on pretentious literature.

The central character in the book is Chandler’s alter ego Roger Wade who, like Chandler, is a genre writer whose work sells, for reasons he cannot fathom, but that wins him no respect as an author. When Wade hits the bottom of the bottle, a frequent occurrence, he spouts self-indulgent nonsense and feels sorry for himself with great eloquence and energy. Wade is Chandler in all respects.

When Chandler wrote this book, we now know, his own wife was dying of cancer and he spent many nights and days with her at the hospital, and turned to the typewriter to escape that reality. One biographer speculates that the book is as long as it is because its composition coincided with her agonising death. A morbid thought, but it explains the mood swings and oscillating character of Roger who is also bearing a different kind of burden from his wife, she being The Dream, as above, or as Linda Loring calls her, ‘the Golden Icicle.’

No review is complete without a barb. Chandler does not manage quite as well with the rich and obnoxious characters, like Harlan Potter or Dr. Edward Loring in this book. Both are at the cardboard end of the continuum. There to be hissed at and booed. Nor is Linda Loring quite right, either, though for different reasons. I never did form a clear impression of her. The backstory of Lennox, Mendy Menendez, and Randy Starr just does not compute.

The book has a foreword, well I guess it is that, but the publisher coyly does not call it that, instead titling it ‘Jeffrey Deaver on “The Long Good-bye”.’ The real mystery is why the publisher bothered to include it. Is the hope that Deaver’s readers will, Pavlov-like, follow him to purchase and read Chandler, or simply to squeeze some more work out of Deaver’s contract? If the former, it is a well-kept secret since it is not trumpeted on the cover (see above) to lure in those Pavlovian readers. If it is the latter, it is a wash-out. Deaver’s remarks are few, banal, and trivial, as well as factually incorrect when he writes that the story takes Marlowe to Mexico. Not so. Marlowe goes no further than Dr Verringer’s ranch in Los Angeles county. Deaver’s main reference to the text is the opening lines, perhaps he got no further. He also says Chandler’s prose is like Hemingway’s. Yes, he does! Staccato. That is Hemingway. Short and sharp. To the point. One point is one sentence. Subject, verb, and object. End. If it has to be said, Chandler’s prose is not like Hemingway’s. Really, Jeffrey!

In 1954 the ‘New York Times’ reviewer, Anthony Boucher, said it was the best of the best, and Chandler’s peers voted it an Edgar award. Boucher also remarks that this novel has a strong theme of social criticism about the society and situation that produces these crimes with less of the sardonic resignation of some of the earlier Marlowe novels.

It took Hollywood twenty years to get around to it, and then to make a hash of it. Nuf said on that subject.

This publisher changed Chandler’s ‘tires’ to ‘tyres’ but stuck with ‘z’ in ‘organize’ and ‘finalize.‘ At least once a ‘he’ appears where it should be a ‘she’ and elsewhere we have ‘ice’ for ‘eyes.’

One question I always ask the inner Elmore Leonard at the end of a novel is, ‘Could I edit it down in length?’ In this case, if I worked at it I would cut and shorten a few scenes and reduce by, say, half-a-page. It all adds up, even Roger’s drunken ravings, tedious though they are to read.