My project on presidents of the United States extends to some also rans, and this is the first one I have read about. Others on the also ran list include Henry Clay, Harold Stassen, George Wallace, and Eugene Debs. A varied lot. I also have my eye on Jefferson Davis, an American president who was not a president of the United States, like Sam Houston. I also include the last Hawaiian monarch for the future.

Category: Presidents

Mr. President Fillmore

Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President by Robert Rayback (1992). Recommended.

The Thirteenth President. Another succeeding vice-president who did not win an election, like John Tyler before him and Gerry Ford after.

Famous for: Maynard G. Krebs referred to him as Fillard Millmore to the repeated and visible annoyance of Mr. Promfritt, and he was also mentioned in ‘What’s up, Tiger Lily (1966)?‘ Students of Cultural Studies will grok these references; others will turn to Wikipedia.

Though Fillmore was anti-slavery he was intimidated by the magnitude of freeing seven million slaves and hoped for a gradual method and so did nothing. In an effort to maintain its North-South axis to make it a national party, the Whig party in 1848 capitalized on Zachary Taylor’s fame as a successful General from that era’s invasion of Mexico. Taylor was a Louisiana slaveholder. To balance the geography and the position on slavery, Fillmore agreed to join the ticket as a New Yorker who was anti-slavery but not an abolitionist.

Taylor treated Fillmore as every vice-president was treated. Ignored him entirely. Then Taylor took ill after a year and four months in office and died. Overnight Fillmore became president.

He had served in the New York state legislature, he had served three separate terms in the House of Representatives in Washington D.C., and he had been comptroller (chief financial officer) of the state of New York. He brought to the Presidency long experience of finance which he was good at, patience at working with committees, and a national outlook born of his long association with the Erie Canal and commerce along the shores of the Great Lakes.

The burning issue of the age was the existence, perpetuation, extension, or extinction of slavery, and its evil twin the tariff, which the South felt taxed it for public improvements in the North. The admission of new territories and states in the West was the kindling for these issues. Why? The addition of new senators would disrupt the balance of power in that body.

Fillmore supported, defended, and executed the Compromise of 1850 as a way to reduce the flames of insurrection, civil war, rebellion, invasion, riot, and the like. That meant enforcing the draconian fugitive slave law. Just as no state can decide which laws to obey and which to ignore, neither could a citizen, let alone the first magistrate, decide which laws to obey and which to ignore, despite his personal feelings, he reasoned.

As president he promoted industry, innovation, commerce, and business in the hope that national prosperity would lessen the heat in the extremities of the body politic. He encouraged trade with China and Japan and supported a railroad and then a canal across Central America to speed trade with the Orient. He warned first the French and then the British off Hawaii.

The aspirins of commerce did reduce some of the fever pitch but the effects soon dissipated. In 1852 one of the architects of the Compromise of 1850 proposed scrapping it, namely that Little Giant from Illinois Stephen Douglas. Go figure! All the old grievances and animosities re-emerged as if preserved in amber with every details in place. Nothing forgotten; nothing forgiven.

Should Fillmore seek the Whig nomination for another term in 1852? He dithered like a Libra though he was born a decisive, if lazy, Sagittarius. In the end Winfield Scott was the Whig nominee and was trounced by the Democrat Franklin Pierce.

Fillmore went into retirement in Buffalo, but his wife died within a month of leaving Washington DC and his only child, a daughter, a few months later. Thus at a loss he travelled through Europe and Asia, and flirted with re-entry politics.

By 1856 the Whig party was moribund and Fillmore joined the American Party, the political front of the Know-Nothing Movement [think Tea Party] and the rabid anti-Catholicism which was a reaction to the tidal waves of immigration occurring in East coast cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Hartford, Brooklyn, New Bedford, Providence, Trenton, Baltimore, Wilmington, Charleston, New York, and more. It was also anti-black. His vice-presidential running mate was Andrew Jackson Donelson, a nephew of Andrew Jackson. Fillmore evidently thought he could tame these nut cases [think John McCain] and discovered he could not [ditto John McCain]. He came a distant third to James Buchanan and John Frémont. His vote made no difference to the outcome.

That ended his political career. He made another European trip and was much feted as a former president, crossing paths with The Little Magician, Martin van Buren, who was in Europe. Fillmore returned to Buffalo and in time re-married and became a man for local good works. He was on every committee for a hospital, a school, an orphanage, a library, a bridge, a hard road, a railway crossing, a sewer line, a pier on the Erie Canal, and the University of Buffalo where he served as Chancellor raising funds for many years. Many of these committees met in his home and he was the real and titular chairman of many. How many ex-presidents have done as much tangible good, I dare not ask.

Though he disliked Republicans for happily embracing a Northern only party (Lincoln got not a single electoral vote in the South and no popular votes beyond Maryland and Kentucky) which he feared would, as it did, lead to civil war. Once the civil war came he organized a home guard of the superannuated and paid for its uniforms. There were recurrent rumours from the outset of the Civil War that Great Britain would intervene from Canada to revenge itself on the United States and so this guard was as much a message to British officials in Canada as to Confederates.

At war’s end, he advocated moderation toward the defeated South but his voice was no longer heard.

Despite those wits Woody Allen and Maynard G. Krebs, Fillmore did a great deal of good first by holding the union together in peace for his term, and then materially in his home town of Buffalo. His name is found on many schools, hospitals, bridges, and the like. A honour that has so far escaped Mr. Krebs. Of Mr. Allen, I (prefer to) know not.

The book is well documented. When an assertion is made there is a reference to a source. The first hundred pages or so are pretty dreary as it traces his origins and early life, but the prose sharpens as his political career unfolds. The last third of the book offers some well judged observations and striking turns of the phrase.

It is part of series but does not read like a completed template the way the presidential biographies read in the series edited by Arthur Schlesinger, Junior. Rayback was professor of history at Syracuse University when the book was published.

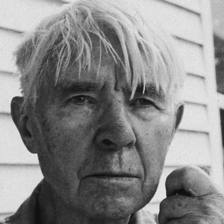

Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and The War Years (1925).

There are scores of Lincoln biographies. I have long been dimly aware of a multi-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln by that poet of the Great Plains, Carl Sandburg, but eight volumes was much more than I wanted. In the oral version from Audible it runs to 44 hours. However I did notice that there was a one volume abridgement. That then was the obvious choice. A biography of the most famous son of Illinois by the most renown poet of Illinois.

All the well known stories are there and I shall not retail them.

New to me

Length and variety of his militia service

Travel down the river to New Orleans

Early and unequivocal objection to slavery on moral grounds in public statement occasioned by pursuit of runaways slaves into illinois

His gradual drift into politics because government could build bridges, dig drains, etc that this small community could never do. Local improvements, they were called at the time.

Saw Zachery Taylor and William Henry Harrison who both later became president.

By 1837 Lincoln opposed slavery on moral grounds, but accepted it in the South because of the Constitution.

As a mediator he learned from his father’s example of dealing with eight children of a blended family in a one-room cabin. Defuse the situation and illustrate with humor

He spoke up on local improvements and because he had learned to read and write, others who could not do either turned to him to prepare petitions.

He became a state representative as Whig, worked hard at committees, reports, speeches

He saw and served in some run away slave case in Illinois.

He was a one-term congressman as a Whig, campaigned for other Whigs in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky.

Lincoln voted several times for the Wilmot Provision to prevent slavery in new territories and states.

In his notebooks Lincoln puzzled over the morality, constitutionality, legality of slavery in whole and in part for years.

He concluded it was immoral since 1837, only indirectly constitutional in the States that had it a when the constitution was agreed, but fugitive slave act was legal, made by congress.

So he wanted to stop spread of slavery to other or new states, stop slave trade bringing in new slaves, but not for ending it since it was legal and partly constitutional in South Carolina and its ilk and since there was no way to cope with one million slaves in seven states who would be made free overnight and impossible to work out how to do it gradually, So on practical grounds there was no solution. Abolitionists seemed to have no plan for what to do if slavery were abolished, rather like all the Greens today who scream immediate action without a thought for consequences. He would have preferred to keep the Missouri compromise but it lapsed with the Compromise of 1850 which was a hodgepodge of deals and concessions much too delicately balanced to last.

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party arose (reminds me of Tea Party!)

Lincoln supported immigrants to vote, to get citizenship quickly and they voted for him.

The number of immigrants at the period is enormous 12,000 a month in Chicago, not all stayed there but went on to Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska.

When the Free Soil Party morphed into Republicans at Ripon Wisconsin (an event no longer celebrated on the Republican National Committee website, such is the pernicious influence of the ideologues) Lincoln had no baggage as an old time Whig, he was from the West and fresh and energetic, and he wanted the presidential nomination in 1860.

He seemed to like being at the centre of things in Illinois legislature and got the ambition.

In a four-way race he won the electoral vote on the popular vote in the larger, northern states. The Southern states started seceding from the Union long before he took the oath of office in March 1961.

Lincoln the president was slow, thoughtful, pragmatic, thick-skinned, patient, mindful of his limitations and those of others. Not to be stampeded by cabinet, nor by generals, nor by the press.

Scurrilous animosity of many in the House and the Senate is hard to credit but it is palpable, and only occasionally silenced. Even Lincoln’s re-election did not shut them up. Th calumny heaped on him by Senate Republicans, war democrats, peace democrats, abolitionists, to say nothing of the Confederates beggers belief.

The restraint in the Emancipation Proclamation was to try to prise the three border states and Delaware away from the Confederacy by not confiscating property of slave holders in those states.

He found slavery objectionable not because of the equality of blacks, but for the debasement it brought to the master. More and more though he did realize that blacks were not only sentient but more. Frederick Douglas and other blacks he met lead him along this path, as did they blacks in the Union army, about 200,000 of them by 1865.

Lincoln’s 10% plan. Those states partly occupied by Union army in 1862 and 1863 like Florida, Louisiana. If petitioned by 10% of males citizens computed against 1860 census he proposed that these state be permitted to form a loyal Union government and to rejoin the Union. For example, Louisiana would have a rebel government in Shreveport and a Union government in New Orleans.

Congress would not agree for a variety of reasons: for some the states which seceded had committed suicide and were no longer states at all, for some these states should be treated as conquered territory under military occupation, for some this plan was a sneaky Lincoln way to get more Republican voters first to get re-nominated instead of Chase and then to get more electoral votes in the general election, for some the were constitutional and legal technicalities that would take ages to be resolved through courts. Were now free blacks to sign these petitions? The House and the Senate would not seat representatives or senators from these ersatz states for all of these reasons and more. This was a mistake, Lincoln thought, because it made fighting on the only choice for some who might otherwise lead a reconciliation. The war between executive and legislature never ends, and there are few truces.

Later in the war Lincoln also tried to set up local governments in East Tennessee that had always been loyal so to protect the loyalists from revenge of losing Confederates. Again congress resisted on analogous grounds.

Lincoln toyed with offering to buy slaves remaining in Deep South to end the war. He claimed it would be no more expensive in money than continuing the war and it would save lives and the destruction of property.

Lincoln ignored distinction of church and state several times a national days of prayer.

Scores and scores of personal petitions to Lincoln and he heard and read just about all of them, and often conceded the exception they asked. That bothered me because I have always resisted making exception for the one in front of me because (1) there many equally placed who were not in front of me for whom I was going to do nothing and (2) I did not want to encourage others to present their petitions to me. My thought was that if here is a reason to make an exception it should be written into the rules. Sandburg does nothing to analyze or assess Lincoln’s response to these petitions.

The endless flood of office seekers even in the dark days of 1864 would be enough to slay a lesser man.

Of all the wonderful remarks Lincoln made, these two say it all.

1. ‘My policy is to have no policy’ (p. 239). An oft repeated remark. Imagine saying it today.

Lincoln was not an ideologue. His goal was to preserve the Union and on Monday that might mean X and on Friday it might be doing -X. If an analogy serves considers a sail boat. To make harbour amid winds and tides sometimes a captain must oversteer to port and at other times oversteer to starboard. These is no inconsistency in these variations, though every immature journalist will declare that there is, having face no bigger challenge than finding a parking place at work.

2. ‘Mr. Moorhead [a very young know-it-all], haven’t you lived long enough to know that two men may honestly differ about a question and both be right (p 660)?’

This remarks explains why he was not an ideologue as per the first remark.

In these 800 pages there is no poetry, and very few examples of Sandburg’s capacity to elevate the mundane to majesty with the sheer energy radiating from the page in his poetry. He also lapses into the present tense in depicting the assassination.

There are too many chapters which list events that do nothing to develop Lincoln, the man, or Lincoln the President.

After the early years the book is about Lincoln the president. No much about the man, relationship to wife or children. Was he religious, I cannot tell? Nothing about attending church and only show him once or twice consulting the Bible, but instead relying on his folksy stories, though the moral of many of these stories could have illustrated from the Bible.

It has no sources or bibliography. Opening preface eschews footnotes.

If Woodrow Wilson had lost the 1916 election

Hypotheticals are often very entertaining, and sometimes, though rarely, informative.

Woodrow Wilson concluded in October 1916 that he would lose his bid for re-election in November against Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican nominee. As a constitutional specialist Wilson had always deplored the hiatus between the early November election and the inauguration of the new president in March of the following year. During that three month period — the lame duck period — the incumbent had no legitimate authority though the formal powers remain.

Charles Evans Hughes

In 1916 the lame duck would be no laughing matter with submarine warfare a weekly occurrence off the Atlantic coast of the United States and Europe burning in an endless war on a gigantic scale while Japan sharpened swords in the Far East and eyed Mexico. In that situation Wilson had no wish to exercise the formal powers shorn of a popular mandate. Moreover, he thought the people’s choice should take on the responsibility immediately.

He made a secret plan to accomplish that end while staying within the Constitution. Here is how he proposed to do it. As soon as it was official that Hughes had won, he would dismiss the Secretary of State, Robert Lansing. Wilson would then appoint Hughes to be Secretary of State. While Congress is not sitting the President can make acting cabinet appointments like this as a temporary expedient until Congress reconvenes. Once Hughes accepted the appointment, Wilson would ask his obliging and unambitious Vice-President Thomas Marshall to resign. Without a doubt Marshall would have readily complied. (Lansing would have almost certainly resisted but he served at Wilson’s pleasure and at the end of the day would have had no choice but to stand aside, willing or unwilling.)

With the way then clear, Wilson would himself resign, and by the existing line of presidential succession the baton would pass, absent a Vice-President, to the Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes who would also be President-Elect. Wilson’s supposed that this could be done within three days or even less once the election results were known. Hughes had only to travel from New York to Washington and say ‘Yes.’ Of course, Wilson hoped against hope to win, so he put the plan which he had typed himself in a desk drawer and waited.

On election day the result was close, and in 1916 reporting results was slow and sometimes uncertain since journalists sometimes jumped the gun. (No comment.)

It seemed by late evening on the East coast that Hughes had won. Hughes went to bed believing he had been elected President of the United States. But he woke up to find that California had voted for Wilson and the left coast was enough to keep Wilson in office. The secret plan went into the locked filing cabinet of history. Would a president today think so hard about the best interests of the country and be prepared to concede to an opponent to serve that interest?

In 1933 the XXth Amendment to the United States Constitution reduced the gap between the election and inauguration from early November to January and re-routed the Presidential succession, after the Vice-President, through the presiding officers of the House of Representatives and the Senate before going to the Secretary of State.

There are two competing principals. The first is that a successor should be someone aligned with the president and au fait with current developments in the executive, hence the Secretary of State as the most important cabinet office should be third in line. That principal applied until 1933, despite Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s remark when President Reagan was shot in 1981.

The second principal is that the successor should be an elected official with broad responsibilities, hence the presiding officers of the legislatures. While not members of the executive, they are engaged with the daily processes of government.

Eight of 44 presidents have died in office. In each case the successor was the VIce-President.

By the way, Hughes had a long and varied career in public service: Governor of New York, Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court, Secretary of State, Justice on the International Court of Justice, and Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court.

A. Scott Berg, Wilson (2013)

Recommended to students of history, international relations, presidents, and biographies. As to the latter, this volume is an exemplar.

Woodrow Wilson was articulate, precise, committed, strong, and strove for a higher purpose than the next opinion poll. He owed nothing to anyone in politics, having entered as a clean-skin with no baggage. But he expected blind loyalty from those around him, not because they owed anything to him but because he was right! He was also one-eyed, a racist, a self-made martyr, and careless of others.

Only stereotypes are consistent and simple.

After the generations of political corruption following 1865, first Populism and then Progressive aroused the electorate. That tide lifted Wilson, first to governor of perhaps the most corrupt state of New Jersey in 1910, and then to the Democratic presidential nomination in 1912. Thanks to Teddy Roosevelt’s third party, the Republican vote was split and Wilson won. Equally, though, one might think TR split Wilson’s progressive vote. Think of Clinton, Bush adult, and Perot in 1992.

Wilson resisted the pressure to join the European war, until German unrestricted submarine warfare aroused public opinion, thanks to the irresponsible journalism of the Murdoch press, oops, the Hearst press, and his own ire. The latter was probably the more decisive of the two to Wilson. But he believed what he said, the United States entered the war to fight for a principle, unlike all the other combatants who were fighting for territory and survival, by the way that principle was the freedom of the seas. This is a foundation stone in the mystique of American Exceptionalism.

The war and the peace that followed forever defined Wilson’s administration, but before getting to that a few other things should be noted. He initiated several enduring practices: the news conference with journalists, presidential addresses to Congress, and the income tax. He appointed Louis Brandies to the Supreme Court who changed American jurisprudence. He allowed his son-in-law racially to segregate the Treasury Department which had previously been integrated in a small way. He supported female suffrage but did not think it should take the form of a constitutional amendment, though he did relent on that. He vetoed Prohibition on the same grounds.

But most of all there was first the war and then the peace. The Western Allies were in dire straits when the United States entered the war. Yet Wilson insisted that American troops would only enter into combat when they were trained and then as a unit, not as piecemeal replacements to be used by English and French commanders as cannon fodder. This insistence, made face-to-face by the United States commander Jack Pershing, led the Allies to form a single, consolidated command, after three years of unco-ordinated slaughter. That in itself was a strategic accomplishment.

Against the even more depleted Germans, when the United States Army did enter combat, fully trained and superbly equipped, it had successes that vindicated Wilson’s insistence in his own mind. He was, as usual, right.

The Peace Conference was a circus like never before. Because Wilson promised the American farm boys he sent to France to die and to become blind, diseased, paraplegic, or to suffer a long painful lingering death from mustard gas in a hospital in Ohio in 1920 that this war would be the last one, in making the peace he strove to uphold his part of that pledge.

The Fourteen Points he made the basis of American entry to the war promised to re-draw the map of most of the world, and so most of the world descended on Paris to insist that the Little Enders were the Devil’s Spawn and we Big Enders can never abide them.

Meanwhile, France in the person of Georges Clemenceau, proudly bearing the nickname ‘Tiger,’ insisted on emasculating Germany. Wilson wanted a simple treaty ending the war, and a permanent world body — the League of Nations — subsequently to work out all the details of implementing the Fourteen Points. France wanted a detailed treaty that would forever eliminate Germany as a threat to France, and finally only agreed to the League of Nations to secure American loans to rebuild Eastern France. To get the League Wilson gave way on French demands, though Wilson said at the time that these demands, unchecked, would lead to another war. Right again.

Then Wilson had to sell the League of Nations to two-thirds of the United States Senate. Opponents in the Senate thought it would embroil the United States thereafter in European politics.

In the midst of this struggle with the Senate, Wilson had a stroke and become a virtual recluse for the last years of his second term. His wife, Edith, hid his incapacity (with connivance of his physician) even from cabinet, and in time he partly recovered. Ever a small-town, many in Washington at the time referred to President Edith since she determined who saw him for many months. The petitioner would leave the matter Edith who would decide whether to show it to Wilson and, if so, she would often edit it to a few sentences. Most petitions went unanswered. In the hiatus postmasters were not appointed, zoos were closed, soldiers remained in Europe, medicine was not distributed in response to the Spanish Flu, goods piled up at ports not cleared by Customs, passenger ships could not off load travellers in harbors because Immigration officials were understaffed… Concealing his disability was unconstitutional, illegal, unethical, and probably immoral. She did it as therapy for Wilson. He had to believe he was still president to recover. Love makes us do things we would never do for ourselves. (On President Edith see Gene Smith, When the Cheering Stopped [1964]).

To this reader, Wilson was not on the job for several long periods. When Ellen died he went into a numbed shock. When he courted Edith, he could only think of her, working it the White House only an hour or two a day. He spent six month at the Paris peace talks. He was fully and partly incapacitated for six months. His two month speaking tour for the League in 1918 took him out of the White House. All of that adds up to about two years when his mind was not on the day-to-day work of the executive.

By the way, Edith attended Jack Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961 shortly before her death.

Wilson retired and then had to make a living since there was no presidential pension. He tried law but he would not take a case involving a client he disapproved of, this did not work since he disapproved of almost anyone capable of paying his fee. In the end private charity from supporters bought the Wilsons a house and an annuity.

There is a lot more to the story, but these are some of the highlights. My notes on this presidential biography run to 4,000 words. This review is an abridgement of that verbiage. The book is scrupulous about evidence and the judgements Berg offers are carefully circumscribed and limited. Altogether a book to recommend. I did think the Zimmerman Telegram got short shrift.

John Meacham, American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (2009)

Jackson was a man of oscillating moods. Sometimes personable, charming, considerate. Other times raging, violent, bullying. Sometimes humane and broad minded; other times contemptuous, racist regarding negroes and Indians, and provincially narrow. All of these in a single day on occasion.

He was at time proudly ignorant yet more well read than many of his friends and any of his enemies knew.

Orphaned when first his father died and then his two older brothers and mother died as result of British military action, during the Revolutionary War. He forever thereafter hated England and suspected it of any and all nefarious actions against the United States.

During his military career he took a paternalistic interest in his soldiers, refusing to leave a single one behind on march, even that meant every officer, himself first, had to walk, giving up their horses to pull wagons and litters. On the other hand he was a tyrant about obedience to the point of execution.

He hated indians beyond reason yet he adopted and raised in his own home an orphaned Indian boy found while his men were massacring a tribe. He wanted to clear indians from the south as they had been cleared from the north, freeing the land for plantations and cotton and thus more slaves. He was an advocate of slavery and completely indifferent to blacks, yet 500 free men of color (in the phrase of the day) were instrumental in his great victory in the Battle of New Orleans, along with about 100 Choctaw indians. But a racist is a racist.

He liked to surround himself with young men, as acolytes, but perhaps also substitutes for the younger brothers he did not have.

He identified himself nearly complete with the country as the family he never knew. Insults to it were insults to him. Insults to him were insults to it in his mind, or so it seemed to some observers.

The mediating institutions created by the constitution stifled the people and supported the privileged, he supposed. He won more votes but had fewer electoral votes than John Quincy Adams in the 1824 elections, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives which promptly (s)elected Adams. The mediating institutions included the Electoral College, the elections of senators by state legislatures, the appointed for life of Supreme Court judges, and the Bank of the United States, which separately and together limited government in the interest of the privileged, he thought, who peopled those mediating institutions. In the 1828 election Jackson won in a four-way race.

The Nullification Crises began in the 1820s and continued for a decade when John C. Calhoun, having resigned as Jackson’s Vice President, argued that South Carolina would choose which federal laws to obey and nullify others. He ever referred to secession. Jackson feared that the state(s) would destroy the union.

At the time Russia in the Pacific Northwest from Alaska to Washington along with the British from Oregon to Quebec in the north, and the Spanish and French in Mexico and the Caribbean surrounded the United States and in his eyes conspired against the continuation of the union. Predators all. Enemies with and without the gates.

The nullification crises was precipitated by an international agreement signed by the Federal Government that permitted seamen to have the freedom of the city while in port. That meant blacks on English, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and other merchant ships could walk the streets of Charleston as free men.

South Carolina objected and then overruled this agreement by jailing any black sailors who set foot ashore while their ship was in port! That action breached an international treaty duly ratified by the Senate and signed by the president of the United States.

The South Carolina justification was that free blacks would by example produce unrest in slaves, might foment slave rebellion, assault white women because they have no civilised control, would be used by the English to destabilise and divide the States….. And the sky would also fall.

Jackson had a constant battle with the Bank of the United States to support local improvements, like roads and bridges. What we call today infrastructure loans to states, counties, towns, etc. The Bank had no interest in bridges over rivers in Tennessee or hard roads in Georgia.

The tariff added, it was claimed, 40% to the price of goods consumed in the south and produced in the north behind tariff walls. The tariff gets tied up with states’ rights, along with slavery, as part of the dominance of the union by northern interests. Ergo to a Calhoun, abolition is a smoke screen to dominate the south and keep the tariff, and the Bank.

Then there was the Petticoat War between his niece in-law Emily and the wife of cabinet secretary Talbot. Emily was determined to show Washington DC snobs that she, from the wild frontier of Tennessee, adheres to the highest standards of propriety and so will not receive Mrs. Talbot, who wed Talbot before her divorce from her previous husband was known to her to be concluded. Moreover, Mrs. Talbot came to the Talbot marriage with a dubious reputation. (But nothing worse than had been said about Rachel Jackson.) So Mrs. Talbot was three times over not to be received: bad reputation, divorcee, and bigamist.

Emily was the wife of Andrew Jackson Donelson, who was Jackson confidante and private secretary, and an ersatz son to him. Jackson likewise was a kindly patron to Emily until the Petticoat War became the talk of that small town on the Potomac.

The Little Magician, Martin van Buren, tried several times to broker a peace between the two ladies, but each time Emily either dithered, or agreed and then revoked her agreement.

Meanwhile, Calhoun and Henry Clay are vultures circling, preparing for their own runs for the White House in 1832. John Quincy Adams, who Jackson roundly defeated in 1828 is sulking and very ready to plot Jackson’s downfall. He might help Clay but probably not Calhoun, since Adams is pure New Englander.

While Jackson was ready to send the Federal army to the Blackhawk War in Illinois it was over before Winfield Scott could get there. He started the First Seminole War to move indians out of Georgia and Alabama first into the swamps of Florida and then across the Mississippi. That is why there is a Miami in Ohio.

Jackson rejected Henry Clay’s proposal for national day of prayer during a widespread cholera epidemic to keep the separation of church and state.

When the Nullifiers got agitated Jackson had the entire Federal army garrison in Charleston replaced by true blue union men, and he managed to do this on the quiet.

He campaigned hard for re-election in 1832. That is, he went on the campaign trail, speaking, shaking hands, etc. The first time a candidate had taken his campaign directly to voters. Martin Van Buren was the de facto campaign manager as the Vice-Presidential nominee. Jackson triumphed comprehensively in 1832 over Henry Clay: 54% to 36%. There were two other candidates who made up the rest.

The Compromise of 1832 in part negotiated by the Great Compromiser, Henry Clay, combined the Tariff reduction act with the Force Bill. The tariff was lowered to placate Southern planters and the Force Bill, though redundant, explicitly empowered the president to collect the tariff by force, if necessary. Martin van Buren did much of the politicking in Congress to count the votes.

When all else failed Jackson withdrew Federal government deposits from Bank of the United States and shifted them to banks in states. By distributing the monies he won over allies, by withdrawing the funds, he killed the Bank of the United States and with it, Nicholas Biddle’s own presidential ambitions. He later vetoed the renewal of the charter. The Bank funded Henry Clay’s presidential campaign very handsomely, using tax deposits, but Clay still lost.

Jackson’s second inaugural address emphasized the Union that won our liberty from England, the Union that secured our freedom, the Union dealt with the Indians. The Union that made us prosperous through industry and trade. Union secured our lands. Union….. These goods were achieved by Union, not by this state or that. Now picture the results of disunion. Each state will guard its borders. Each state will impose its own tariffs and taxes. Each state ill built only internal roads. And so on. A pretty well made argument for a man with little credit as a thinker.

There was a point-blank assassination attempt by a nutter. Jackson was convinced it was a conspiracy of his enemies working through this reprobate.

When William Lloyd Garrison sent thousands of copies of an abolitionist tract through the United States mail to Charleston, Jackson sat idly by when South Carolina firebrands burned the warehouse they were in. He did nothing to protect the U.S. Mail and in fact asked about legislation to stop sending such material through the mail.

Jackson viewed Van Buren as his successor and the vote for Van Buren as a vote for him, Jackson, so Jackson worked hard for Van Buren in 1836.

I listened to this book on Audible in an abridgement during 20-minute episodes dog-walking or pedaling at the gym. That makes it harder for me to assess the research basis of the book. But I can say that it is not one-eyed. More than once Jackson’s mistakes and faults are noted. And at the end the author notes how great evil can be the commonly accepted practice of the day, namely slavery.

James L. Haley, Sam Houston (2002)

File under ‘Might Have Been.‘ Sam Houston (1793-1863) might have been the 16th President of the United States. So the dream goes, a President Houston would have held the South to the Constitution while defending states rights, and yet found a way to satisfy the demands of the North, economic, political, and moral. With such a president there would have been no Civil War. As it is, he is in fact an American president though not of the United States but of Texas. (The 16th President was Abraham Lincoln, Class!)

Houston was a man of many parts: A staunch unionist, a Southern with unimpeachable qualifications, a hero in three wars, hand picked once by Andrew Jackson that champion of the west, known through the northeast coast as an informative and entertaining speaker, a vigorous opponent of the slave trade, an avowed proponent of states rights, a blood brother to Cherokee Indians, a man who read himself to sleep with the Odyssey and Cicero’s Offices.

Some indication of his political career can be seen in the elected offices he held. He was born in Virginia and went to the wilds of east Tennessee as a young man.

1819 elected Tennessee Attorney-General

1823 elected to the U.S. House of Representative from Tennessee

1827 elected Governor of Tennessee

1836 Elected first President of the Republic of Texas

1841 Re-elected President of the Republic of Texas

1846 Elected to US Senate from Texas and twice re-elected

1859 Elected Governor of Texas

Few are the curriculum vitae that can match that. Then there is his military service.

The list conceals as much as it reveals. The gap between 1827 and 1836 includes three years in the wilderness where he lived among Indians. He resigned as Governor of Tennessee when his bride of one-day rejected him and her relatives thereafter and for years heaped calumny on him. Bound by the code of a Southern gentleman, Houston made no reply. He gained himself in one day a lifelong reputation as a ravisher of women though it is plain he never touched his bride, and in the following three years he earned an equally enduring reputation as an alcoholic. He certainly deserved that for a time. He also found solace in an Indian woman, while still married to that bride.

What chance for such a man in civilized society? A ravisher. An alcoholic. An Indian lover?

What a fall from Attorney-General, U.S. Representative, and state Governor to pitiful wretch living on the charity of impoverished Indians.

Yet the frontier gave him another chance and by dint of his own hands he took it. GTT was the slogan of the day in the 1830s and so Go To Texas he did. There he tried to farm and developed a lifetime interest in agronomy and stock breeding. Having at the third try secured a divorce from his long estranged wife, he married a woman who swore him off the bottle, and he kept that oath. In fact, he became a national temperance speaker. He was completely devoted to his wife, Margaret. Yet he sacrificed everything for Texas, and at one point sold the family home to pay some Texas debts that were in his name.

When the convolutions of Mexican politics produced Santa Anna the Texas War started. Houston had fought in Indian Wars in Tennessee and in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. He was wounded in both and with medicine as it was, the wounds never healed properly. Indeed it is said that on his deathbed in 1863 his old groin wound opened.

He was a temporizer, having seen enthusiastic militia get themselves killed in earlier wars he advocated and practiced restraint and preparation. The Texas Revolutionary Council made him a General and he recruited troops, secured weapons, and trained the men. All of this was ridiculed by the hot heads who urged immediate action. To make matters worse when Santa Anna’s army approached, Houston retreated for he had read much of Napoleon’s destruction in Russia and thought the distances and heat of Texas might reduce the European trained and equipped Mexican Army.

When the armies at last met, he feigned confusion and fear, and this emboldened Santa Anna into several tactical blunders. The Texans prevailed at San Jacinto where Houston was wounded again.

There is much more to the story but let that suffice as a sample.

Houston was Governor when Texas seceded from the Union. He stalled this eventuality as long as he could, finally sitting at his desk while the secessionists acted in the room next door. When they demanded he take an oath of allegiance to the cause of secession, he refused and they declared the office void. At 67 he accepted this turn of events and went into retirement. He died in July 1863.

Between 1861 and 1863 his only forays into politics were to advocate the relief of the conditions of Union prisoners of war in Galveston, and to council dealing honourably with the Cherokees. The former was the more successful of the two.

Note, Houston wore an Indian blanket as a cloak when he took his place in the Senate and spoke there more than once on the terrible record of deceit and perfidy that the United States had visited on Indians. That cloak sent John C. Calhoun into one of his many rages. I rather think Calhoun was the intended audience for the gesture. To find out why, read the book.

The book is brilliantly conceived and written, starting with the Preface that explains why we need to know about Sam Houston and why this book is the one to tell us. It totals 500 plus pages and surveys the previous sixty biographies of Houston and plunges into the original source material. It is the product of fifteen years of research, writes the author. He has no university affiliation and I rather doubt a university would indulge such a project today. The demands of a three-year performance review, the imperative to secure a research grant whether needed or not, the premium on counting publications, and much more combine to make short-terms achievement the path to tenure and promotion.

My only knowledge of Sam Houston before reading this book, apart from schoolboy apocrypha, was the short chapter on Houston in John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage (1955) that likened Houston to an actor standing just out of the spotlight. He was involved in great deeds but it was never quite clear what he was doing or why or how. That seems right in light of this volume.

Houston was capable of working on several levels at once, always had Plan B, C, and D in train if A did not progress. He knew the power of words to focus attention. He tried always to keep his word so that he could trade on it. Even when political difference divided him from friends, he tried to keep the personal relationship alive by letter and succeeded in many cases in retaining the personal friendship of sworn political enemies.

In death he is now more acceptable to Texans. Check this on You Tube

Cut-and-paste because hyperlink insertion does not work.

Warren G. Harding (2004) by John Dean

Now that I have ordered some presidential biographies from Amazon I get notices about others. These I have been ignoring. But one caught my eye, not because of the president, but rather because of the author: John W. Dean. Think about it.

Given Dean’s experiences I thought that alone might make the book interesting. My only residual knowledge of Harding was the innumerable scandals associated with him. Dean would know about scandalous behavior by a president, I thought.

Get it yet? This is the John Dean of Watergrate, the president’s counsel who would not lie for his president and who kept meticulous notes, and made himself the star witness at the Senate hearings of Sam Ervin. That president was Richard Nixon.

As it happens Dean is from the same town in Ohio as Harding. This book is part of a series edited by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., so it has two strikes against it. It is written to a series template, and it has Schlesinger’s name associated with it. Many of the authors in this series are interesting but odd choices, for example, the novelist Louis Auchincloss on Theodore Roosevelt, television newsman Douglas Brinkley on John F. Kennedy, and presidential aspirant Gary Hart on James Monroe. It also includes one title I have already read, James Madison by Gary Wills. None of these authors is a scholar, though Wills is a man of penetrating insight, Auchincloss a fine writer, Hart is from Colorado, and Brinkley used to talk to Chet Huntley (his associate on the national news).

I will say something about the book itself at the end, but for now let’s see what can gleaned about Warren G. Harding. He was a middle class, small town newspaper editor and owner. He was a born networker who genuinely liked people with an organized mind and a good memory for faces. He avoided conflict and seldom took sides. He was handsome and commanding in his physique. Sounds a perfect Libra! Though he was born on 2 November.

How did he become president? His own political career began in Marion Ohio then to the Ohio legislature, then lieutenant governor, then U.S. Senator, where the personal qualities mentioned above stood him in good stead. Ohio was solidly Democratic but Harding was a Republican. In that smaller talent pool, he looked good. At each stop along this cursus honorum he travelled widely and spoke to any gathering, mostly Republicans.

Nationally the situation was vexed. Teddy Roosevelt’s efforts to regain the Republican nomination in 1912 had rent the Grand Old Party. William Howard Taft and Charles Evans Hughes who had run against Woodrow Wilson had been unable to heal and unite it. But when Wilson had a debilitating heart attack in 1919, the Democrats were leaderless, too.

In that gap Harding emerged. He got the Republican nomination on the tenth ballot after three days. By then there was pressure to choose someone and he was inoffensive, and no doubt some like Mark Hanna, the eminence gris of Ohio politics smoothed the way. When it was clear that Wilson would not seek an unprecedented third term, and that had been bruited about for a time, James Cox got the Democratic nomination. James who? More important than James was his vice presidential running mate. One Franklin D. Roosevelt. But I digress.

It was an Ohio affair between the Senator from Ohio, Harding, and the incumbent governor of Ohio, James Cox. Eugene Debs was on the Socialist ticket and got nearly a million votes from a jail cell in Atlanta. H. L. Mencken once said Debs spoke with a tongue of fire, but that is another story.

Harding took the oath of office in March 1921. He convinced Charles Evans Hughes to serve as Secretary of State, and let him get on with the job. Hughes tried to integrate the United States into world affairs to repair the damage done in the struggle for the League of Nations.

One of Harding’s best and most lasting achievements was to create the Bureau of the Budget with a director appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate who reports directly to the President. The President submits a budget to Congress which then amends it into an unrecognizable form to accommodate the interests of the constituents of the majority of Representatives and Senators. Congress sends it back to the White House, and then the serious negotiations begin. It is a fiction because after all the sound and fury there was never any check on how the money was spent. Indeed there was no way of knowing if it had been spent or on what. With his experience as a small businessman Harding did not like that and much to his credit he created this small but powerful and independent agency. But… It came back to haunt him.

The only thing I knew about the Harding Administration was the Teapot Dome scandal. It seems that three of Harding’s cabinet, at least, used the public trust of their offices to defraud the government in a big way. All were alike in a way, they sold government assets (which had ballooned during World War I) at unbelieveable prices to old pals in business and got enormous kickbacks, sometimes delivered in $100,000 units in black Gladstone bags to the office. Subtle, not!

The Bureau of the Budget did notice the decline in government assets valued at millions for peppercorn returns. The Bureau of the Budget did draw the President’s attention to these events several times. Dean has it that Harding tried to persuade the malfactors to stop. Others say, my source is Wikipedia, that he had long experience of doing the same. In any event, they did not stop, and the press got the news and passed it on. Think what the Sage of Baltimore had to say! (That is H. L. Mencken for the slow wits.)

Once one scandal was examined, it lead to another, and another. And it all unravelled.

While in San Francisco, Harding died in office of a heart attach at age 59 in August 1923 at the height of the Roaring Twenties, succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge. From San Francesco, Florence Harding, herself very ill, by telegraph asked an Ohio confidante in the White House to burn Harding’s files. Dean has it that she did this to protect President Harding’s reputation. There is much speculation about why she did this. And that is all it is: speculation, just what passes for news today on the ABC. There is also speculation that she killed him.

The fact is that papers were burned in those days before presidential libraries. But the confidante did not burn everything, and again there is no evidence to explain why. Many boxes were stored in the third basement of the White House coming to light years later when restoration were done. In time these papers found their way to the Harding Association in Ohio in the middle of the 1960s they were catalogued and available.

However there is no evidence that Dean consulted these papers. This book is not based on original research in any sense of the term ‘original.’ Rather it is a synthesis of the existing biographies of Harding, with a slant toward rescuing the reputation of this fellow Ohioan and fellow Republican. Too often the conclusions that rehabilitate Harding seem to come from the air. The strongest claim Dean can make to defend Harding from culpable knowledge, if nothing more, is the absence of evidence. But as that other Republican ideologue Donald Rumsfeld, with whom I once crossed a street in Washington D C, said: the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence. Instead the book tries to cloak Harding in some kind of mist. More pages are spent on his ineffectual and inconsequential dealings with some matters that appeal to contemporary sensibilities, like race relations, than the core matters of his administration.

The book is replete with clichés that neither describe nor explain, like ‘party elders,’ ‘tough going,’ etc. I am sure lawyer Dean is expert at briefs, but sustaining a narrative for 150 pages without lapsing into the vagaries of cliché is a different discipline. Anything that exonerates Harding is taken at face value and anything that does not is clouded over with doubts. Perhaps this is a courtroom tactics but it fails on the page.

John Tyler: The Accidental President by Edward Crapol

I did know that John Tyler had been president. Why? Because of that very early campaign slogan, ‘Tippiecanoe and Tyler, too.’ Look it up, if it is unknown. I knew he succeeded Harrison, but that is all I knew. Yet when I read Borneman’s biography of Polk’s emergence and election, Tyler seemed an interesting if remote figure.

He is widely regarded as a failure, no doubt in part because he did not win an election in his own right.

So…..

Continue reading “John Tyler: The Accidental President by Edward Crapol”

James K. Polk by Walter Borneman

The publishers statement: The first complete biography of a president often overshadowed in image but seldom outdone in accomplishment. James K. Polk’s pledge to serve a single term, which many thought would make him a lame duck, enabled him to rise above electoral politics and to outflank his adversaries. Thus he plotted and attained a formidable agenda: He fought for and won tariff reductions, reestablished an independent Treasury, and most notably, brought Texas into the Union, bluffed Great Britain out of the lion’s share of Oregon, and wrested California and much of the Southwest from Mexico. In tracing Polk’s life and career, author Borneman show a Polk who was a decisive, if not partisan, statesman whose near doubling of America’s boundaries and expansive broadening of executive powers redefined the country at large, as well as the nature of its highest office.