History is just one thing after another.

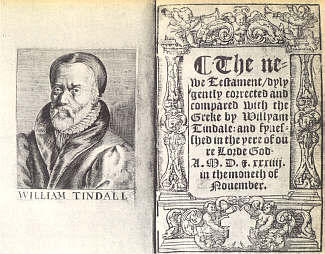

1537 William Tyndale published an edition of the New Testament Bible. It was the first English translation based on early Greek and Hebrew texts and the first English translation to be mass produced.

1797 The first Spanish merino sheep’s back arrived in Sydney. They came from Escorial. (Been there.) The MacArthur’s developed Elizabeth Farm. Been there.

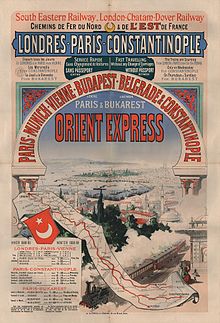

1883 The Orient Express started. Been to the places named on the poster and once rode on a leg of the Orient Express from Munich to Vienna. Not the grand train of legend but the everyday service from one end of the line to the other.

1927 Work began on Mount Rushmore monument. Been there. The Crazy Horse monument will look like the image in white in the foreground. Expect a Trump Tower to blot the landscape all too soon.

1957 Sputnik launched. I heard its beep beep in the junior high school auditorium where we were gathered to hear Walter Cronkite put on a brave face this accomplishment for (Red) mankind. No I cannot link sound recordings to these entries, though I have tried. It can be found on You Tube.

3 October in history.

1863 U.S. President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the fourth Thursday in November to be a national day for Thanksgiving. He was prompted by the Union victory at Gettysburg. It has remained thus since. The previous practice of Thanksgiving had been ad hoc and on various dates across jurisdictions, and not a national holiday.

1906 An international conference on telegraphy in Berlin established SOS as the signal of distress. Three dots three dashes three dots, ergo: …—… It does not stand for anything, but was chosen because it was distinctive.

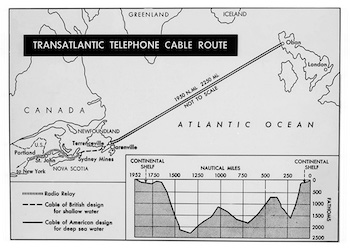

1927 A trans-Atlantic telephone call between Canadian Prime minister McKenzie King and British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin occurred.

1935 Tasteless egg whites were dubbed Pavlova after Anna.

1952 The British explode an Atomic bomb on Monte Bello Island in North West Australia. Britain is still paying compensation to the aboriginal people who were there exposed to radiation.

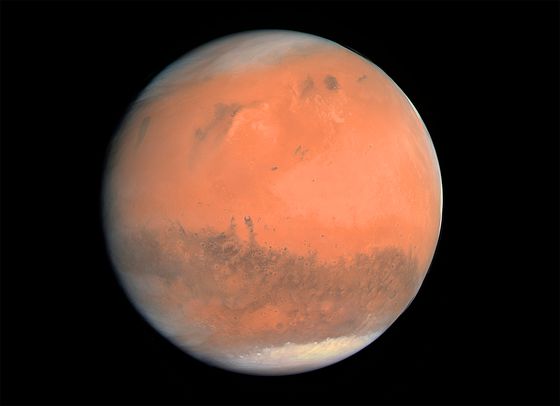

‘Mars in the Movies: A History’ (2016) by Thomas Miller.

GoodReads meta-data is 292 pages, rated 3.7 by a paltry 9 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: All hail, Nerdboy!

The title says it all. Thomas Miller has compiled, annotated, watched, summarised, and commented on every movie (in the English-speaking world and more) that features Mars and some that do not and others that should. He includes cartoons, animations, documentaries, shorts, serials, and features. Did I say comprehensive? Comprehensive.

Miller’s telling is personal and there are asides and tangents but they, too, add to the overall impression of our fascination with Mars and the way it is manifested in art and life, including his own life. He climbed trees as a boy, looked at the stars, marvelled at stories of spaceflight, and became determined to work for NASA, and did. However, on with the show….

I was surprised at the long list of movies included. Many of the feature length fictions were familiar, but there were surprises even so. There is a chronological list at the end. The chapters are thematic: voyages to Mars, invasions from Mars, life and living on Mars…… But strangely nothing on Mars Bars.

It was a shock to find out how many versions there have been of H. G. Wells’s ‘War of the Worlds’ after the 1953 inaugural. I have lost count but typing that title in the IMDb will yield quite a harvest of literal remakes, and then there are those with slightly altered titles, and still others with different titles but the same storyline.

Just as B movies used to be turned out in ten days or less to capitalise on the success of A movies, so today made for television, steaming, or DVD movies are produced as clones. And just as some B movies are far better for being simpler and more direct than the bloated A movies they imitate so some of the straight to DVD movies are better than the big ego productions of Hollywood.

Consciously the author’s scope seems mainly the USA. There are few references to England, apart from H. G. Wells as above, and less still to films originating in other parts of the world. There is no mention of the Mars mission portrayed in ‘Murder in Space’ (1985) from Canada. It may be that the paucity represents reality and if so, that itself might have borne comment. Why are Americans more fascinated with Mars than others.

Miller ridicules many critics who pan movies. His suspicion is that many critics have to earn their spurs by being negative, and so will deride a movie on flimsy ground. And once a major critic does this, the herd follows in the tracks of the bigger beast. Really? Would self-respecting professional film critics for such prestigious mastheads as the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Colliers, and so on be that lazy, arrogant, and stupid. Really!

Can there be evidence for such cartels? Miller lists in chronological order nearly word-for-word repetitions in reviews from dozens of critics, one repeating the other, it would seem, unless there is a mighty busy god of serendipity. He even shows how mistakes in the first major review, say a typo in a character name, are reiterated in the flock that follows. Amen, Brother Thomas, lay on the wood.

What is surprising are the times – two are documented in these pages – when a producer dams his own film as it goes on release. This damnation may be explicit or implicit, and perhaps represents some corporate pathology being played out in public. Yes, dear viewer, even the snow white Disney Corporation has been known to denigrate its own product.

Less informative is Miller’s fascination with the opening credits of movies. He cannot fathom why critics do not comment on the scene-setting effect of opening credits, citing some examples of very effective opening credits, like those of the 1953 ‘War of the Worlds’ and some very ineffective ones. Point taken. He then repeats the exercise. He then refers to it again, and again. And reverts to it at the end. I believe him when he says he sometimes puts in a DVD and watches only the opening credits before moving on to something else. I also believe him when he says his wife finds that annoying.

Did I say Nerdboy above, or what.

Another of his pet peeves which gets ground into the eyeballs by repetition is the lag in communication back and forth between Mars and Earth. He nails this of course, but then pounds it in and in and in. Yet at the same time he waxes lyrical about a completely inaccurate and anti-scientific account of Mars, including sunbathing, of ‘Robinson Crusoe on Mars’ (1964), discussed elsewhere on this blog. Instantaneous interplanetary communication will condemn a movie to the sin bin in his eyes, but sunbathing on Mars with a monkey will not. Go figure.

‘Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science’ (2017) by Karl Sigmund.

GoodReads meta-data is 480 pages, rated 4.17 by 107 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction.

Verdict: Only for the cognoscenti.

The Wiener Kreis was one of the engines of Twentieth Century science, including philosophy and mathematics. It began as a loose discussion group and evolved into a more tightly knit and organised group with satellites. The Kreis – Circle – waxed and waned with the circumstances and fortunes of its members until reality kicked in the door in 1938.

Those associated with it comprised a Who’s Who of intellect, e.g., Albert Einstein, Kurt Gödel, Hans Reichenbach, Carl Hempel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap, Richard von Mises, Karl Menger, Moritz Schlick, Ernst Mach, and more. Chaps all if it has to be said. Bertrand Russell and other English-speaking intellectuals beat a path to its door. As a whole the Kreis published monographs and the journal ‘Erkenntnis’ (Knowledge). Springer continues to publish it to this day.

Its members together offered logical empiricism though many preferred to say logical positivism, because the empiricism was made of air. It was the big bang that created analytic philosophy that dominated English-speaking philosophy in the Twentieth Century. Its exemplars include A. J. Ayer, Hans Kelsen, Karl Popper, Willard Quine, Frank Ramsay, and Lord Russell himself and all who followed his star.

They were united in a holus bolus rejection of metaphysics and often suspected one another of just that tendency. Some of the descriptions of seminars sound rather like Communist Party cell self-criticism sessions. Of course, there were many intellectual differences among the members. This book also gives weight to their personal and social similarities and differences. Many were Jewish and that made life increasing difficult for them and those around them in Mitteleuropa.

Many of these folk were oddballs, indeed, but the Emperor of Strange had to be Ludwig Wittgenstein who has sometimes been worshipped as a saint in philosophy and at other time derogated as the selfish malcontent that he was. Whoops, my objectivity slipped on that one.

Heir to a vast fortune, he lived like a vagrant. Some find that admirable. He was perhaps born to be a stylite. (Look it up.) He did not use the fortune to any good purpose and in time much of it was seized by the Naziis for their purposes. Even so he always had money available though he seldom spent it.

When acolytes appealed to him for financial help, he dismissed them on the ground that poverty was ennobling. Thanks, Ludi, they all said with a smile. Some of these appeals came from very desperate people, sometimes Jews who had been his students, in the 1930s. There is no record that he ever did anything to help another person. This saint attended only his own soul. He also managed to ruin the careers of more than one acolyte, but that is too complicated to explain here.

The times were indeed demented as illustrated in the case of one of the more sober and sane members, Moritz Schlick, who ran the show for years. A disaffected student blamed Schlick for all his woes and festered on this belief for years, sending him threatening letters, stalking him, accosting him on the street. The forbearing Schlick endured this burden for some time until finally he reported it to the police. Once the police became involved the student blamed Schlick even more for his troubles.

Now get this. The student got a gun and tried to shoot Schlick. He bungled it and was arrested, founded insane, and locked up….for eighteen months when he was released. Got another gun, and tried again. Another bungle. Arrested again. Locked up again. Released again. Got another gun, and third time successful. If that reads like a bad plot, sit down, because it gets worse.

The murderer was tried and sentenced but by this time time no one cared. He served a few years in a prison and then was released whereupon he became an ardent Nazi and later served as a guard in a death camp for Jews. After the war he was whitewashed, as were so many Austrians. In Germany a German with that record would have been barred from public service. Not so in Austria. (Indeed some Germans relocated to Austria because of that difference.)

He became a post-war bureaucrat, prospered, and retired on a state pension. When a biographer of Schlick wrote that he had been murdered by a deranged student without giving his name, the murderer sued for libel and won. It sound like something that Fox News would do today. The dead victim became of the villain and the villain became the victim!

One of the most attractive figures in the constellation of the Vienna Circle was Otto Neurath, and we pay tribute to him most days. Go to a public men’s room and on the door is a pictograph representing a man. Pointing the way to the train station is a picture of a train engine, not a letter T. A sign indicating a traffic turning-lane shows a car over a curved arrow. Look at the pictorial icons on the smartphone screen. These are downwind traces of Big Otto. Having given up on Esperanto, he tried to create a pictograph language with 800 words and a grammar of isotypes. Big Otto worked closely with his wife Marie on this. She was one of the few woman around the Circle. His personal and often repeated motto was ‘We must improvise.’ The more so they did when on the run from the Naziis.

While these thinkers argued to the death over protocol sentences and other esoteria, the world around them caught fire and took some of them completely by surprise, while others had seen it coming and fled. They spread the seed of logical positivism far and wide in the English-speaking world, though at the end of the war Austria did not want them back. Rather it preferred to appoint and promote people like Schlick’s murderer. The example is the effort made to block Kurt Gödel’s return to Vienna. Grotesque but true. Austrian university authorities went to great lengths to insure he did not return to Vienna. Yet every mathematician in the world — apart from those in Austria — regarded him as THE Genius of the ages.

Karl Sigmund near the building where the circlers circled.

Karl Sigmund near the building where the circlers circled.

I went to Grad School because I wanted to study Plato and Aristotle and their kind. Instead, I got ‘Language, Truth, and Logic’ and other such tomes. Through five years of graduate work I never did read Plato for a seminar. But Ayer, Russell, Popper, Hemple, Quine, and [see above]. Looking back on it, it was a form of discipline, rather like learning a dead language (Latin or Greek), in which form triumphed over content, process over product. It was a time when philosophers and hence we cousins in political theory were trying to be scientific.

The PhD was the hardest thing I have ever done. The coursework was hard. The oral exams were hard. Writing the dissertation was hard. The defence was hard. It was all hard. It’s been downhill since!

I listened to this book on Audible and found it entertaining though some of the expositions were hard to follow. The reading is most accomplished. The difficulty was following the abstract and abstruse thoughts without seeing the words.

History today! Read all about it.

1492 Spanish drove Moors out of Granada. Been there. Napoleon ordered the destruction of the Al hambra. It survived that order and that man. Seen that.

1866 J. Oosterhout patented a tin can with key opener. Eaten some sardines from such a tin.

1903 President T Roosevelt closed the post office in Indianola MI because citizens had attacked Minnie M. (Geddings) Cox (1869–1933), the post master because she was a woman, worse, a black woman. She had been appointed in 1891.

1919 Cogadh na Saoirse: Dáil and Sinn Féin outlawed. Seen the pock marks in the central Post Office.

1947 Mahatma Gandhi marched for peace in East-Bengali to reduce conflict between Muslim and Hindi. Neither of these camps were as amiable as the British.

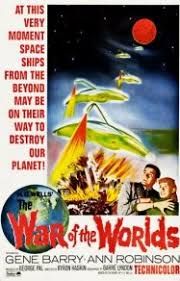

‘War of the Worlds’ (1953 but first shown on 11 March 1954)

IMDb meta-data is runtime 1 hour and 24 minutes rated 7.2 by 28542 raters.

Genre: Sy Fy

Verdict: Classic

In the hills of California far from Grovers Mill a large, flaming meteor lands with a mighty wallop. It starts a forest fire and the locals turn out to quell the fire, and marvel at the object. It’s big; it’s hot. Nearby reading the script is Top Scientist (perhaps on his way from ‘Atomic City’ [1952] and counting down to ‘The Twenty-Seventh Day’ [1957 ], both reviewed elsewhere on the blog).

Top puts on his professorial glasses. The yokels gasp in awe. Top figures out the meteor came from Mars. Probably he read the luggage tags on it.

Then the meteor hatches the first Martian weapons tripod. The three stooges approach it in peace with a white flag as they do in the westerns and are cindered from their trouble. A sky pilot muttering the Lord’s Prayer is likewise toast. More meteors arrive. More tripod war machines appear and lay waste to everything, houses, roads, baseball card collections, churches, tanks, firetrucks, cannons, vending machines…. Nothing is spared, not even World Series tickets!

These tripods did not come in peace. They are landing all over the world, Dubuque, Indianola, and elsewhere.

In desperation the ever reliable Lee Tremayne nukes them. Kaboom. Yet the tripods, now shined by the radiation, keep coming with their red heat rays.

There follows a flight, and a reunion, and the Martians die. Seems they were anti-vaxxers and had no shots before travelling to Earth.

There are some marvellous scenes, as when the first Martian is glimpsed through the window of a wrecked house, and then the tendril that reaches out later. There is an effort at science as Top and his colleagues at the Pacific Smarty Pants Institute examine the evidence.

There is satire of the media. When the Martians start to appear, the journalist wants to know what colour their socks are. As always getting right to the point is the press. The trivial and childish initial responses of the media are realistic.

None of the formidable weapons the Yankees can bring to bear even dent the Martians tripods. Not even Little Boy. They are powerless against this invader.

The panic is likewise realistic. The mob destroys the very science that might save them. Has a contemporary ring to it, doesn’t it.

Thanks to the science at Pacific Smarty Pants we know the Martians are unvaccinated puny little stick figures in latex. Hence when exposed to the pollution, FM radio, smog, haze, advertising, pollutants of California, they croak. The end.

What every one remembers who saw the original on the wide screen is the tripods, the periscopes, and the creatures, all and always in threes. Three eyes, three tendrils, three tripods, tripods. Made the fraternity brothers wonder what else they had three of.

The special effects were indeed special. They remain gripping even in the iTunes version I watched. The wire work was great, though over the years transfer from the original film stock to other media has revealed the wires at work in some versions. This has given a new generation of nitpickers no end of sanctimonious fun.

Producer George Pal included but did not himself understand the irony and satire in the original, e.g., the priest, the bacteria, the media frenzy, the rigidity of officialdom when faced with something new, and the irrationality of the anti-science response. He repeated the jokes without understanding the humour. He then overlaid these with a superficial, stiflingly, and sappy veneer of Christianity. When the local priest walks into the heat ray it is sheer stupidly in the original story, in the film is a noble sacrifice, pointless though it is. And so on.

Pal’s Sy FY curriculum vita is rich and varied, starting with ‘Destination Moon’ (1950). He is described as a happy soul who was also naive in the extreme. In his hands this satire became a warning of a Communist invasion that can only be stopped by praying and singing hymns. It also keeps the tigers away.

By the way the love interest for Top was included at the insistence of the studio executives, and so Pal complied. That late and forced inclusion may explain why she has so little to do.

That wizened H. G. Wells combined with the wunderkind Orson Welles made an enduring franchise out of ‘The War of the Worlds.’ Typing the title ‘War of the Worlds’ into the search box on IMDb will produce a confusing list of hits. Captain Nerd, that is, Thomas Miller, in ‘Mars in the Movies’ (2016) has counted more than a dozen direct replications of ‘War of the Worlds,’ and notes other more tangential derivations.

1 October in history.

1815 The Congress of Vienna started. It brought stability to Europe for nearly a century. A precursor of the United Nations and also the European Community.

1847 Maria Mitchell became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The first woman to be inducted. She was a stargazer, a Massachusetts Quaker who taught at Vassar.

1850 The University of Sydney was founded. It preceded Cal 1868 and the LSE 1895. It followed Toronto 1827.

1867 Karl Marx published the first value of ‘Das Kapital.’ He preferred seat G7 in the Reading Room of the British Library. Sat there.

1946 A dozen major Nazi leaders were sentenced to death at Nuremberg. No comment necessary.

30 September in history.

1199 Moses Maimonides published ‘The Guide to the Perplexed’ in Córdoba. Been there but still perplexed.

1791 ‘Die Zauberflöte’ with that aria from the Queen of the Night premiered with Amadaus Mozart conducting the orchestra in Vienna. Been there and heard that.

1902 Rayon patented. Worn that but no more.

1938 The Munich Accords signed. (Been there.) Alas. See Robert Harris’s superb reconstruction reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Members of the Chamberlain family have said that the Prime Minister meant to say ‘peace for a time.’ The paper in his hand is not the Accord but a letter signed by Adolf Hitler pledging peace.

1953 Auguste and Jacques Piccard descended 3150 meters in a bathyscaph and returned. Not me.

29 September in history!

Pick one to tell someone else. No cheating. One only. Which will it be? Why will it be that one?

480 BC The Battle of Salamis in which the Athenians defeated the Persians. Themistocles’s proclamation is on display in Athens. Saw it in 2007.

1863 Georges Bizet’s ‘Les pêcheurs de perles’ (The Pearl Fishers) opened in Paris and has not closed since. Been to that Opera House.

1903 The land of Prussia required licenses for automobile drivers. Got one myself, but not from Prussia most of which is now in Russia and Poland. The Kaiser went on a picnic.

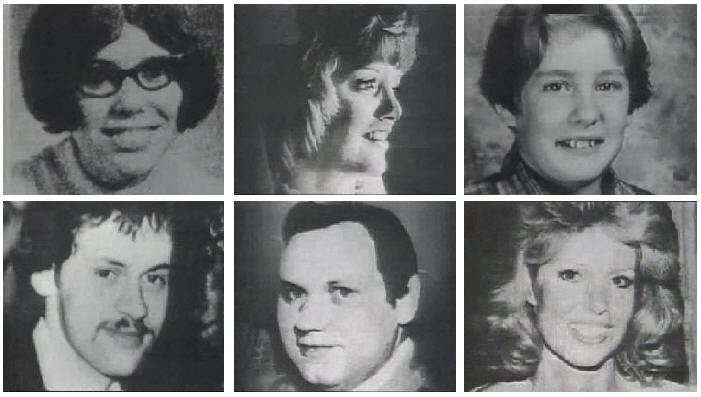

1982 The Tylenol murders in Chicago which remains a cold case, and which led to the tamperproof packaging of medicines in blister packs and more. The first six victims.

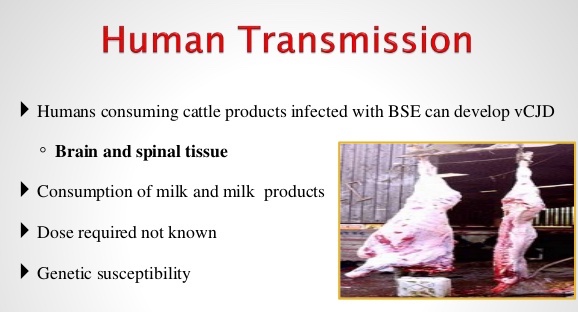

1997 The link was established between mad cows and people in England.

28 September in history.

Come and get it. The day’s history lesson.

1542 Portuguese Juan Cabrillo became the first European to see California when he sailed into San Diego Bay on a mission for the Spanish crown. He claimed it all for his patron.

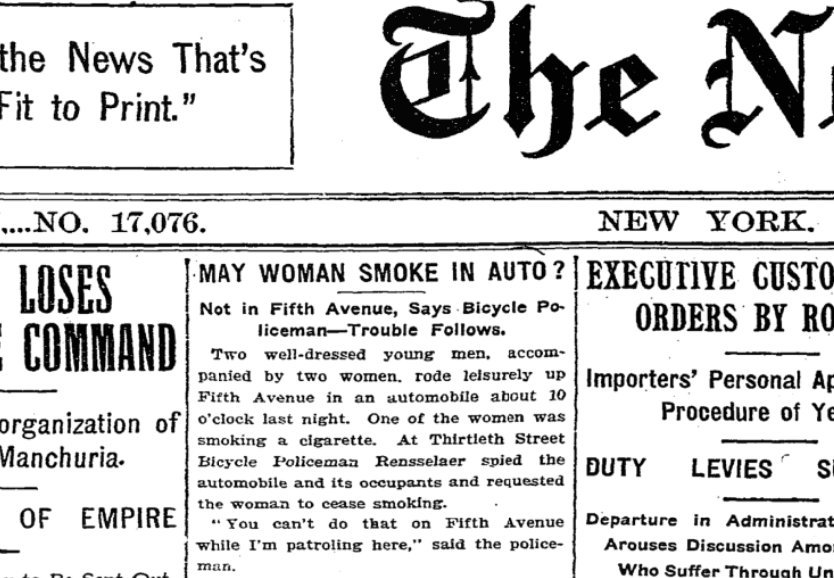

1904 A woman was arrested for smoking in New York City. She was a passenger in an automobile minding her own business, when….

1922 Benito Mussolini led the March on Rome.

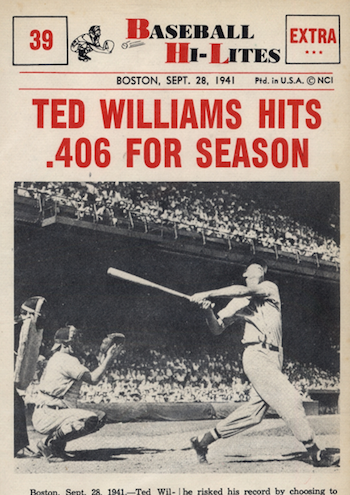

1941 Ted Williams finished the season at .406, the last major league baseball player to achieve that potent consistency.

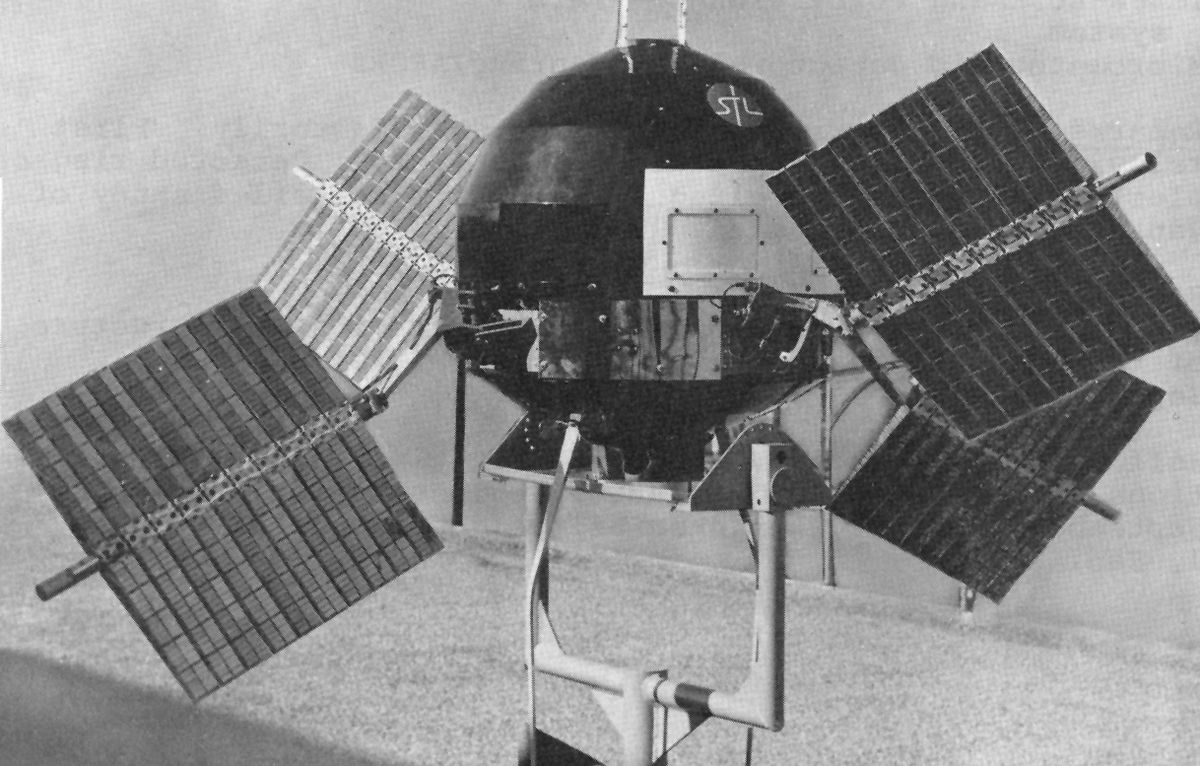

1959 NASA’s Explorer VI took the first video of the earth from space. There is video on You Tube but the files are too large to load on this blog.