The facts from the IMDB: 1 h 53 m and 5.5 from 507

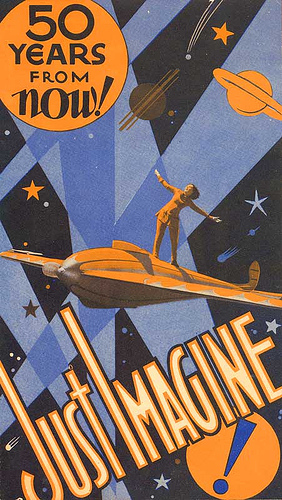

A whopper from 1880, oh wait, make that 1930, but it opens with a comparison of New York City in 1880 with that of 1930 to illustrate the change in fifty years and then projects another fifty years into the future for the story of Romeo and Juliet in space suits, sort of, with singing and dancing. Yes it is that rarity of rarities, a Sy Fy musical, only the second I know of. (Read to the end to find out about the other, or just scroll there.)

In distant 1980 things have come, pace H. G. Wells. Evidently traffic is so bad that everyone uses a personal, fold-up light hover craft to get around. The craft is a light airplane capable of vertical take off and landing, and can hover, as the opening scene shows. In it Romeo and Juliet meet in the air and each sets their craft to hover, while they talk of their troubles.

Troubles? Yes, they have troubles right there in Sky City.

For a start the Volstead Act is still in force, as one of the characters says in a contemporary reference. Fraternity brothers, cover your ears. Moving on.

Think of Plato’s marriage festivals first, to get in the right frame of mind, Mortimer. A man has applied to the Marriage Bureau to conjugate with Juliet against the application of Romeo, whom she prefers. In this world she is not even consulted in the matter. The Bureau decides in the favour of the other chap, whom we shall call OC. OC is of a higher status than Romeo and so gets the wife he wants. Period. End. Well, if it ended there, it would be not one hour and fifty-three minutes long.

Men apply to marry women, but women, as it explicitly stated, cannot apply to marry men. This process is asymmetrical.

Romeo appeals and has four months to lodge a counter application. But how can he raise his status in that time? He is already at the top of his profession as a Zeppelin pilot and there is no way up from there. (Get it, Mortimer? [Probably not]) Not sure why but he does not think of going into management. Guess the scriptwriters did not foresee the Invasion of McKinsey Managers and the havoc their KPIs can bring.

He wanders around the Big Apple and bumps into Igor to whom he tells his troubles. This is just the man Igor is looking for, because he boss, Mad Emeritus Professor 1, wants a disconsolate but experiences Zeppelin pilot to fly his experimental, virginal spacecraft to Mars. To be the first man to fly to Mars and return will give Romeo a super deluxe status and he will easily win Juliet’s hand and all that goes with it. If he survives the trip.

Earlier when he was drowning his sorrows with this buddies, they went to watch, as one does, Mad Emeritus Professor 2, resuscitate a dead man killed in 1930.

He is the Comic Relief, whom we shall call Lazarus. Lazzie tells stupid jokes for the rest of movie. Reviews from 1930 suggest this was instantly detected.

Naming the characters at will is both easy and necessary because in 1980 no one has names but only numbers, e.g. JN-102.

Romeo, one of his drunk buddies, and Lazzie fly to Mars. Gaavoom! And their iSpaceShip hits Mars. There they are greeted by Busby Berkley’s dance company and have a high-ho time.

Though things are confusing because everyone on Mars is a twin, one good and the other a Republican. They get confused. They do look alike.

Every now and then someone breaks into song, and there are many dance numbers. Indeed the Martians are mimes who express themselves in dance, a lot.

The film was enormously expensive to make with all those sets, mechanical contrivances, travelling mattes, and extras, and it bankrupted the studio just as the Great Depression closed theatres. Not a CGI in sight. It was made prior to the Hayes Code and there is much female flesh on display, and some implicit homosexuality. On the other hand, there is little cigarette smoking, which is so pronounced in some other, later Sy Fy films on the Moon and Mars and even in the space ship en route.

In 1930 talking pictures were in the first decade and many of the conventions, camera angles, transition cards, and the like are used. In vaudeville shows there was often a comic or clown on the stage between acts, as one set of performers cleared out and another set up, to fill the gap and hold the audience. That is what Lazzie does here, though in this case he had the reverse effect of clearing the sofa for a time, with his lame, forced, often incomprehensible efforts at humour. Suddenly an urgent need came over this viewer to fill the dishwasher.

Maureen O’Sullivan is in it, before she landed in the jungle with Tarzan, but like most of the other players, she goes through the motions. Marjorie White as her brassy girlfriend is the only one who injects energy and vitality, albeit not creditability, into the proceedings in her scant screen time. The word ‘scant’ also refers to some of her costume, what there is of it.

Among the other appurtenances of 1980 are video phones and televisions, and meals in pills. Buildings with two hundred stories are equipped with light-speed elevators.

Among the songs in this film are ‘Old-Fashioned Girl,’ ‘I’m Only the Words, You Are the Melody,’ ‘The Drinking Song’ and ‘Never Swat the Fly.’ ‘The Drinking Song’ is staged on a dirigible and the ‘Never Swat a Fly’ was a show stopper when, instead of Fast Forward, mistakenly I pressed Pause.

Before condescension overtakes us, pause to consider how well we might do today just imagining 2067? About as well as John Lennon did?

Fritz Lang’s monumental ‘Metropolis’ (1927) had only appeared a couple of years earlier, and many in the audience for ‘Just Imagine’ may have been unaware of it. The ‘New York Times’ reviewer, at any rate, does not mention it. Mortimer, that was a silent movie with a wall of sound for orchestral accompaniment.

‘Time Flies’ (1944) is the only other entry in the category Science Fiction, Musical, Comedy. Believe it or not, it was made in England. In it four contemporaries travel backward in time to the Sixteenth Century to correct Shakespeare’s spelling. Well, what other explanation could there be, Erich?

‘It! The Terror from Beyond Space’ (1958)

From the IMDB: I hr 9 m with 6.1 / 3674.

A creature feature concerning a Mars mission. Here is the set-up. In distant 1973 square-jawed Marshall Thompson is the man-in-charge, but, well, on Mars things happen – off camera. His whole crew of nine has been killed and only he survived to be rescued by a second mission. Marshall is suspected of murdering his crew, since what other explanation could there be, Erich? Marshall does not know what happened. Napping while in command it seems. Even if he did not kill them, and no motive is ever mentioned, he is guilty of malfeasance.

But on the way back in the rescue ship…., yes, down in cargo hold is a very ugly and very large set of bunions. Any one with feet like that is going to be irritable. But what podiatrist would take on such an impossible set of toenails? For convenience let’s give this creature a name, something creative and imaginative: Mars Bar (MB). Where was TSA when this piece of work boarded?

MB sets about murdering the crew of the ship on the return flight while Marshall is locked up, so he is off the hook. No effort is made either to communicate or contain MB, instead the crew, mid-flight through space, get out their war-surplus pistols, rifles, bazookas, and hand grenades which they use with the panache of Hollywood, shooting from the hip. None this blasting bothers MB much, nor does it rupture the ship’s skin. They must have build it it for inside battle. Me, I would have aimed at the toes.

Murdering members of this crew is almost too easy. They repeat their mistakes repeatedly. They open hatches to see what is going on and the opener finds out the hard way. That does not discourage his mates from doing the same thing again, and again…. Until there were (just about) none.

MB stowed away on Mars for reasons unknown, and so comes from a particular place. How that could be ‘beyond space’ as per the title is lost on me.

Spoiler Alert. When all else fails the remaining crew don the well-used space suits originally made for ‘Destination Moon’ (1950) and seen in many films since, including this one, and let the oxygen out and this kills the creature. Quite how the surveyors are going to re-inflate the ship and return home is elided. That the creature needs oxygen is … just said since he parades around in the rubber buff.

Also lost on me was the skull with a bullet hole in the forehead which is produced by one point to prove Marshall’s guilt. No explanation is offered then or later that I heard, but napping I may have been. Yet at no time did MB pack a rod. With feet that like he had no need of a gat.

There is nothing about Mars, though two ships have landed on it. Both were clearly and exclusively American. There are two women in the crew who by turns serve coffee and scream. On the other hand the writers were confident enough in the audience to include an airlock without and explanation and also to a multi-story ship again without stopping to explain it. That is some evidence that the genre was maturing.

The end is the tag line that ‘Mars is death!’ No more missions will go to Mars. Instead the strange creatures called Republicans will be examined.

Still this experience did not deter him from ‘First Man into Space’ (1959) where things were even worse.

Marshall Thompson geared his whole life, it seems, for Hollywood stardom, or so it is said. His family moved to Los Angeles to give him a shot while he was but a boy. He grew into a handsome young man and did all the right things and in 1944 and 1945 when many other Hollywood stars were involved in war work of one kind or another, from active service to fund raising or propaganda filming, he got some parts, but thereafter ‘It! The Terror from Beyond Space’ is what he is best know for. Except for…

Marshall Thompson was so named because his family claimed relation to the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Marshall.

Marshall Thompson was so named because his family claimed relation to the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Marshall.

Yes, ‘Daktari’ in the late 1960s. By some twist of fate he got cast as the veterinarian in an African game reserve and made a success of it. Moreover, even when it wound down, Thompson found he could not let it go and thereafter worked as a philanthropist to raise money for African animals the rest of his days. Though he was upstaged in ‘Dakar’ by chimpanzees and lions, he forgave them and became a friend to they and their kind.

‘Murder in Space’ (1985)

A Whodunnit on an international space mission made in Canada for television with a major cast including Michael Ironside, Wilford Brimley, Martin Balsam, and more. The Conestoga has a crew of nine: two Soviets, two American, one Canadian, Italian, French, England, and East German. This crew has just completed the first Mars landing and exploration and are returning to Earth, a few days from re-entry when things start happening.

The graphic is misleading as there is never a cadaver floating around and no one wears a space suit.

The graphic is misleading as there is never a cadaver floating around and no one wears a space suit.

Contrary to the IMDB summary, the start is the unexpected and unexplained death of a Soviet woman on board, about thirty years old. That engages the attention of ground control in the form of Wilford Brimley. Fearing a Martian pathogen is on board, the ship is ordered to hold position for further analysis. There follows a long distance autopsy using the facilities of the ship and analysed at ground control. This is one the many interesting ideas in the film that are not developed.

The IMDB data is 4.7 / 160.

There are political repercussions to consider and the Soviet ambassador is Martin Balsam who intrudes, ever so tactfully into the proceedings along with Arthur Hiller as the US Vice President in charge of the space program. The more so when the autopsy reveals that the Olga, the victim, was suffocated.

Murder! In Space! That is bad. It redoubles the reason to delay landing. There is worse. Another one of the nine little indians snuffs it due to cyanide poisoning. Yikes! Is this homicidal cabin fever when so close to home, or what? Or what?

Spoiler follows. There follows a convoluted Agatha Christie like unraveling. The East German killed her because she threatened to reveal his homosexuality. Before she died Olga put cyanide in the insulin of the poison victim who refused to help her. Ironside killed the East German in his self-appointed role of judge, jury, and executioner because he figured out he had killed the Soviet. The second Soviet accidentally blows himself up – this is the explosion mentioned on the IMDB — when he responds to a coded order to seize control of the ship.

Qualifications are in order. First as to the explosion. It was not clear to me, and yes I was paying attention, whether the explosion was triggered by accident or it was booby trap to silence the Soviet planted by the Soviet government. While he was fumbling with the gear someone was knocking on his door and that distracted him. Despite the fact that the explosion fatally ruptured the ship, the door knocker walked away. More on the fate of the ship and surviving crew below.

Second, Ironside kills the East German because no one has jurisdiction in space and he would otherwise go free on landing. Really! I would have thought the Soviets would deal with him. Jurisdiction is much discussed but not developed in plot or intellect. It caught my attention because we used space jurisdiction in debate in college. The details have long since been overwritten.

The TSA was not on the job for this flight. Olga had a supply of cyanide for recreational use and the Soviet man had a sub-machine gun in his NRA-tagged luggage.

There is nothing about Mars, the mission, or space flight in the movie. Our nine might well have been on a railway train, a ship at sea, a castle on a hilltop, or cut-off by the weather in Otranto Inn. That was a major disappointment. After the ship is damaged by the explosion, despite the earlier worries about either a pathogen or a killer on the loose, the remaining crew members exit via an escape pod and land.

Likewise I never understood why the US Vice President had the call on an international space mission to Mars. In general I thought the political dimension was well handled, though a needless plot twist was inserted when the Soviet premier changes mid-flight. That is linked to Olga, the first victim, but it seemed a needless distraction. Although none of the other nations figures in the diplomacy.

The Wikipedia entry says the film was made without an ending, and only after some focus group screening, was the explanatory end filmed. Groan. That tells me that no one knew what they were doing or why. It shows.

On the plus side there are women in the crew and there is sex but the women are portrayed as capable crew members with jobs to do and they do them, only once is one of them required to go all female and scream, this from someone with the grit to walk on Mars. But otherwise the film has left behind the puzzle of how a woman could be a scientist that bothered so many men in earlier Sy Fy. A small mercy.

The pressure of the media feeding frenzy is well realised, but rather subdued compared to the reality. But the constant demands by representatives of the media distracts and confuses everyone.

The direction is crisp and the actors are fine. The cinematography is fluid. Ironside was effective as the man in charge who never expected this!

Brimley is always a treat.

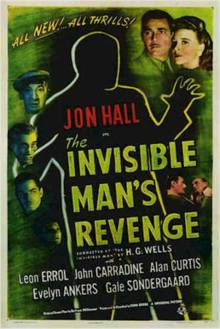

‘The Invisible Man’s Revenge’ (1944)

The last of the Universal franchise of TIM (The Invisible Man) before descend to Abbott and Costello. The credits declare this to be an original screenplay, and the ubiquitous Kurt Siodmak is himself invisible. The story lines from ‘The Invisible Man’ and ‘The Return of the Invisible Man’ have atrophied.

In this outing the invisibility is born of John Carradine, squinting to prove his intellectual credentials, who experiments on birds, cats, and dogs until Jon Hall comes to the door. This is Hall’s second tour on invisibility duty. When last unseen he was saving the USA from a Nasty invasion, when not lecturing on the American Way.

Instead of another mission as a secret agent, Hall is now a homicidal maniac who has escaped from the White House, oops, from an asylum in South Africa. The film opens with him cutting his way out of Qantas class… from Durban on the docks of Southampton. He seems to have surrendered his Yankee citizenship, too, become Hollywood Brit.

He has come to England for revenge on Spider Woman and her insipid husband whom he claims earlier cheated him out of a diamond mine Africa.

Spider Woman

Spider Woman

Spider Woman is no one to trust, but it seems she and her husband did not cheat him or leave him for dead after clubbing him, though he alleges all of this. Reality does not matter to him, in the spirit of the Tea Party, for Hall thinking it is so makes it so and he sets out to bedevil them. After efforts to placate him fail, they put the local plod onto him and he absconds, stumbling to Carradine;s door.

Carradine is ready for a human subject, and here he is! One jab and there he isn’t, now invisible. Special effects follow, one being a darts game in a pub. Oh hum. Then floating glasses and such. The magic, however, has worn off for this viewer.

The twist here is that Hall wants to be invisible to elude the plod but visible at other times to assume a new identity, and to make that transition between the two states he needs blood, and lots of it. Several home-brew transfusions follow, and Carradine pales to dry. Much to’ing and fro’ing follows, all without eliciting much interest. This sanguinary element references the conclusion of ‘The Return of the Invisible Man.’ Hall’s megalomania is also of a piece with the foundation stone, ‘The Invisible Man’ (1933).

In the end Brutus kills him. The end. Brutus? Carradine’s loyal and once-invisible dog which has dogged his steps since the death of Carradine. We cheered Brutus on. At 1 hour and 18 minutes we only wished Brutus had got him earlier.

This outing has shifted genres to Horror and left Sy Fy. This villain is a competitor with Bela Lugosi for blood. One imagines, and if I can imagine it, surely some hack did, too, Dracula and TIM fighting it out in a Red Cross blood bank, like two oenological connoisseurs in a cellar of fine wines. Crash and smash! This idea is copyrighted but for sale, cheap. Contact the agent, if he can be seen.

In sum, TIM has gone back to his origins in England and there are no references to the war, though this was made in Hollywood in 1944. No doubt the assumption was that audience had enough of war entertainment, as the casualty lists grew.

Spider Woman, Edith Holm (Gale) Sondergaard (1899–1985), won an Oscar in 1936 and was nominated again in 1946. She quit films in 1949 and left Hollywood when her husband, Herbert Biberman, was pilloried by HUAC and she only reappeared on film in 1969. Our loss. In the interim she trod the boards in New York City.

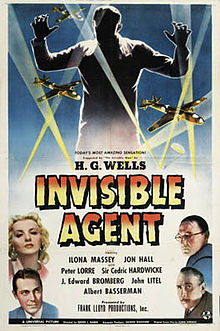

‘Invisible Agent’ (1942)

More shenanigans from an invisible man with a screenplay by Curtis Siodmak, also known as Curt and Kurt. In 1942 the more Anglo-Saxon name Curtis appeared in the credits. And this title is very much a wartime period piece.

Lobby card.

Lobby card.

From get-go our hero, Jon Hall, is accosted in Nowheresville USA by thugs led by the ever so British Cedric Hardwicke, all dressed in mufti, and Hall knows instantly that they Nasty Germans. Cannot fool a Yank in 1942. Hardwicke knows invisibility when he sees it since he saw it in ‘The Return of the Invisible Man’ (1940) in which he led the bill. Since the invisible man punched his lights out in that film he became a Nasty and is out for celluloid revenge.

In this series the name of the invisibles has varied, Griffin, Radcliffe, Nerks. Is such confusion the inevitable result of invisibility, ahem, because maybe the lady did not know which was whose. That is the conclusion of the fraternity brothers.

The Nasties are Naziis. They want the formula for invisibility or else…. Hardwick is a bloodless reptile, but the scene belongs to the understated Peter Lorre as a malevolent Japanese along for the fun. Hall is a printer and in his printshop is a guillotine paper cutter. Shiver! Lorre thinks of ways to use it, on Hall.

The Nasties are overmatched, four thugs and a Nip against one Yank on his home court. He fights them off and they scurry away.

That Japanese is Mr Kentaro Moto who has answered the call to the flag and is now working for Japan and not the International Police. Yikes. He is perfectly sinister but he was useless in the fight. Strange how he had forgotten all that judo.

Hall is then asked ever so politely, not a waterboard in sight, to give his formula to the USA government, but he gets all pompous and refuses because it is too terrible a secret to reveal. In earlier films the serum was dangerous to the recipient because of its side effect (megalomania, aka Potomac Fever) but that is largely omitted here. The terror is in the capacity to be invisible and the evil that invisible evil men would wrought. As already seen the invisible woman was resistant to Potomac Fever.

Then the spinning newspapers report Pearl Harbor, and remembering Moto from the printshop disturbance, Hall goes to a Big Committee meeting in D.C. Who these men are is never explained, and some speak with European accents and some look more oriental than Moto ever did, amid the many Midwestern American accents at the table. Hall offers the formula, and speeches of gratitude are heard, but he has a caveat. Oh?

Only he can be inoculated, and he must do it himself, with the drug because…. Is it the side effects? Is it the secret which might fall into the wrong hands? Not clear to this viewer.

Now as a weapon in war, what good is an invisible man, naked, barefoot, and unarmed? Would invisibility have helped the Finns in the Winter War? This question is never pursued, we just segue to the secret agent, the spy, the invisible agent spy: bare of foot, naked of clothes, and without a weapon in sight.

It seems the Nasties are planning to invade the USA, and the question is when is Invasion Day. Kind of reverse of D-Day in Normandy. They will launch this attack from Nasty HQ in Berlin! Amazing logistics will be needed for that in 1942 This practical matter is later brushed off with a throw-away reference to a suicide bombing fleet leading the way (for the U-Boats laying a bridge across the Atlantic).

Hall is parachuted into Berlin to find the date. Yes, Berlin, well Potsdam a few klicks from Berlin,though conveniently the road signs are in miles. At headquarters the Nasties are Abbott and Costello.

Mind, while parachuting down, Hall strips off his flight gear and that is a marvellous effect. He is invisible when he lands and the Nasties run around crashing into each other. Hereafter the invisible man, while remaining invisible, draws a great deal of attention to himself. The fraternity brothers recognised a kindred spirit in this ghostly presence.

Since he had no training, it seems also that he has no sense. He all but tweaks the noses of Nasties, leaves a trail even Abbott and Costello could follow, and generally makes it known that there is an invisible agent at work.

Moto and Hardwick get the word and converge on him, setting a trap, one even Homer Simpson would have detected, but not this ingenue who blunders in and when apprehended blames everyone else!

Moto and Hardwick get the word and converge on him, setting a trap, one even Homer Simpson would have detected, but not this ingenue who blunders in and when apprehended blames everyone else!

Not to worry, the Nasties even in Berlin are overmatched and Hall has little trouble in breaking jail, getting the exact date of the invasion, himself bombing Berlin for good measure, and flying off. Whew!

The special effects of invisibility are good. Here he is as a spectral presence which is far more eerie than complete invisibility though he is usually the latter.

In addition to the parachute drop, our invisible hero takes a bath and as he soaps himself the lathered parts of his body appear, mainly his leg, an echo of the stocking scene in ‘The Invisible Woman’ (1940). Earlier there was a scene of his footprints in straw of barn, an echo of a scene in the original ‘The invisible Man’ (1933). Food, drink, telephones float in the air.

K(c)urt(is) Siodmak with a line from this movie

It was 1942 and Hall gives lectures time and again on the American way. If all of that was so important maybe he should been more responsible in concealing himself. The propaganda was dished by writer Siodmak, born a Polish Jew, and no doubt heartfelt since he had fled Hitter’s Germany a decade before finding his way to Hollywood, but it is also leaden and seems out of sync with the Abbott and Costello hijinks our hero gets up to when not at the podium.

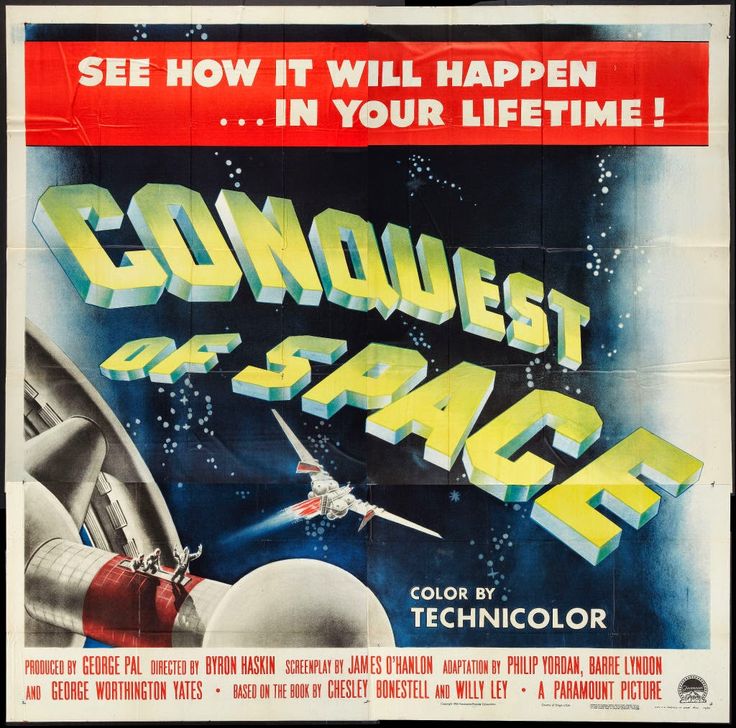

‘Conquest of Space’ (1955)

George Pal produced this title and he always tried to get the science right, and left the screen play and direction to others in a division of labor, but, of course, he selected and hired the director and writer.

In this case he hired a director who specialised in special effects and knew nothing about directing a drama and a writer, well that is the problem, not one writer but several writers each of whom stitched in this and that and evidently no with a whole perspective. One output of the rumour mill has it that the studio executive in charge of production concluded during filming that the story lacked drama and insisted on adding the Oedipal element half-way through, while cutting the budget, a McKinsey manager avant le mot.

Pal’s groundbreaking ’Destination Moon’ (1950) had many critics who found it more like a boring documentary than a dramatic film. They said

it lacked humour

it lacked tension

it lacked sex appeal

it lacked humanity

it had too much science

it was too expository

it had too much vastness of space

and so on.

Pal went with the flow(s) and this is the result. All those elements ostensibly lacking in ‘Destination Moon’ were shoe-horned into the film. It is easy to picture the Happy Hungarian, as Pal was known, with a clipboard checking all these elements off the production schedule. The result is a mishmash of checklist items.

In a giant space station, the inevitable wheel because scientist at the time thought it was the way to the stars, a superior elite of the world’s best are preparing for the first moon landing. These individuals are the best of the best of the best of the best, a reference to the Men in Black for the cognoscenti. Each man is a volunteer, each man, for there are no women on the wheel, but yet there is still sex appeal. Intrigued? Read on.

That is the set-up and the ride is downhill from there. The writers reanimate the conventions of World War II submarine movies, where all the men were draftees, few were trained in more than turning a wrench, and the captain had sailed yachts. These superior spacemen complain about everything, want to go home, and are all Americans, almost. If this crew is the best Earth can do, better to stay at home.

Amid the crew are two foreigners, a Japanese and an Austrian. The Japanese gets one speech where he goes on about chopsticks as the miserable future for mankind, while the Austrian’s big scene is as hard to describe as it is to watch. Suffice it to say here it is pure kitsch.

The humour is supplied by an uneducated engineer who cracks jokes, I think, at intervals. Check. By the way this is a reprise for ‘Destination Moon’ where the radio operator did that.

The humanity must be all the whingeing by members of this superior elite who just want to go home. They are just regular guys, not super spacemen. Indeed.

The tension is maxed between commanding officer father and subordinate son, as if this is any way to run a railroad. Though there is a similar paternity in ‘Riders to the Stars’ (1954) from the typewriter keys of the ubiquitous Curt Siodmak.

The scientific exposition remains though, interspersed with lame jokes from the lame joker. Yes, these supermen in space still do not know the basics. All that training, all the preparation, all that work in building the space station wheel which was emphasised at the outset and gravity is still unknown.

‘The sex appeal?’ I hear the fraternity brothers asking. In another parody of World War II tropes the crew of the space wheel watches a movie with dancing girls and an uncredited Rosemary Clooney singing about love in the sand, an excerpt from ‘Here Come the Girls’ (1953). Sex appeal? Rosemary Clooney?

When that excerpt mercifully ends there are excruciating video messages for some crewmen. The Joker’s girlfriend drips 1950s celluloid sex on the screen, and then that Austrian, remember him, Ross Martin (who was born in Poland), who seems to combine German, Austrian, and Jew in a stereotype. His mother sounds like something from a Yiddish burlesque. Poor Ross. More humanity. Her private message to her son is screened in the recreation hall in front of the whole crew. Sensitive New Age management there.

The special effects are well done though many are borrowed from other films. But the vastness of space is there, and the movement from the wheel to the rocket and back is nicely done on a sled. And there is one memorable scene when the body of Ross Martin. who got in the way of an old reliable meteor, is consigned to the stars, though again the procedure mimics burial at sea.

Who had to tell his mother? I wondered.

As Launch Hour nears, the impossibly handsome William Hopper, before Perry Mason took him on, appears to tell the elite team that their mission is not the Moon but MARS! Gasp! Groan! More whingeing follows from the supermen volunteers.

Walter Brooke as the general is top-billed, a journeyman television supporting actor. Who knows why Paramount with its stable of talents chose him is anyone’s guess. He seems flat and robotic, in what I suppose the director thought was military discipline. There is a subplot about space fever that comes from being in space too long or maybe from watching this film.

Since the mission has crept to Mars, the general asked for volunteers and some of the whiners volunteer so they can whinge some more, and a small crew sets off for the Red Planet. As they do the general gets religion from out of the black and blue of space. He goes bonkers and tries to scuttle the rocket ship and kill them all. Wow! Eric Fleming, before heading them up and moving them out on ‘Rawhide’ is his son and socks him. This sock saves their lives but infuriates one of the crewmen whose unexplained loyalty to the general is so great that seemingly he would rather be killed by him than see the general’s son sock him on the chops.

Even though the general has gone Tea Party feral, the son leaves him at large, while they land on the Red Planet, which looks like the red hills of Georgia. These space explorers show no interest in Mars and wait for the opportunity to leave. The general continues to gum up the works, until…. Remember Oedipus.

The Japanese plants a seed and it grows.

See, Georgia. Trite as it is on screen there is an important point which we would recognise today but which was missed both by the scriptwriters and the audience at the time, namely that we Earthlings are destroying our own planet and the mission to Mars is to find new resources, including food. It turns out the earlier speech about chopsticks had a point in its garbled nonsense.

They have to wait on Mars for the next launch window, though nothing about that is explained, though gravity had to be explained earlier, and thanks to the general their supplies are low. They make no effort to record observations or explore the red planet. However, it snows and with the water from that they can power the rocket back home! Well that is what it looks like.

But the snow is for Christmas and we have another derivation from WWII movies, with a schmaltzy Christmas on the front line. All the while the loyal crewman mutters threats to the son. It is all so stagey that no one is interested. least of all this observer.

Eric Fleming had a career on television which was cut short, when he drowned in an accident while filming on location.

This film concentrates on the psychological aspects of life in space, and not the technology, nor hairy and scary aliens. That is a welcome focus but the execution is so diluted that most viewers will miss the point. It is diluted mainly by all the tropes from World War II movies, the static direction, the wooden acting, and the mechanistic checklist. Moreover, there is little interest shown in space and exploration by this crew who just want to go home.

One famous scene is the dining hall. Yes, there is a dining hall per all those World War II movies, but in this hall there is no food, but only pills. Yet there is still a vast hall with cafeteria tables and the whole crew assembled for the service of pills. Another pointless trope that undermines the awe and mystery of space travel.

‘Nemesis’ (2014) by Jon Martin

A superb novel that traces the early life and career of the Spartan Gylippus of the Fifth Century BC. He was a major figure in the Peloponnesian War and the spine of the novel is derived from Thucydides’s ‘History’ of that war.

There is much insight into the inner workings of Sparta. The author knows the detail well but wears the learning lightly, though making no concessions to readers by spelling everything out. The reader is left to figure it out when Greek terms are used or to refer to the glossary at the end.

The divisions in Sparta are well realised. There are personal and clan rivalries and also personal ambition. As one character says much later to Gylippus from the outside the Spartans appear as one man. Hardly. The author makes the Spartans all too human, at times vain, myopic, venal, ambitious, resentful. But those tensions are played out behind many curtains.

Athenians are no better and their fractious conflicts are largely played out in the open air.

The contrast to Gylippus is the Athenian Nikias, another giant from the pages of Thucydides. Nikias does all in his considerable power to avoid war, and rejects command twice when it is thrust on him, and yet he dies in the war on duty,

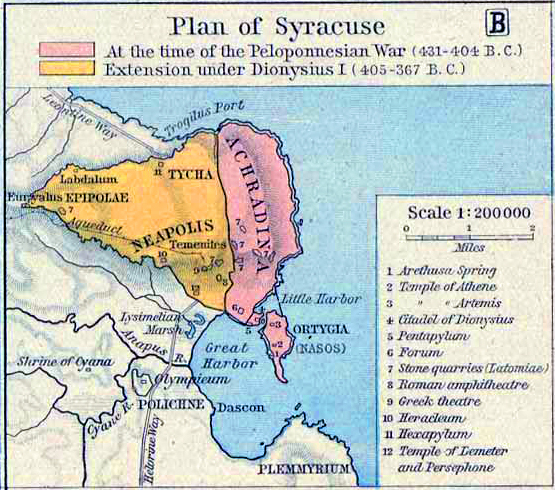

Readers of Thucydides will know that the crucible for both Gylippus and Nikias was the Athenian invasion of Sicily. The arc of the story begins with the Athenian reduction, pillage, and rape of Melos, where the cry ‘The Athenians are coming!’ anticipated the German cry ‘The Russians are coming!’ in 1945.

That was Athenian democracy at work. The opening scene of the Athenian slaughter of chained Melian prisoners and then forcing the surviving women to stack the bodies of their faheres, husbands, sons, and burn them are gruesome indeed. After that the rape begins, followed by a slave market. Two young girls escape, and though that was unlikely, as a plot device it takes them to Sicily for later events.

We went to Melos in 2007 as homage to this atrocity.

On a pretext Athens invaded Sicily to seize the island and its agricultural wealth now that the Persians have closed the Egyptian grain trade. The expedition was gigantic and command was divided and proved contradictory, aggressive in one instance, and passive in another. Nikias searched for a political solution to accommodate the appetite of the demos on the Pnyx in Athens, while the other generals wanted a battle in which to be a hero. There is no pretence at unity among the Athenians.

Melos had appealed to Sparta for help in deterring the Athenians, but Sparta did not act.

In Sicily the democratic city of Syracuse likewise appealed to Sparta, and Sparta sent one man, and that was enough. ‘Throughout time allies did not sent to Sparta for ships, or money, or soldiers, but for one man,’ said Plutarch.

The divisions within Syracuse are well realised, and full of the irony of reality. The staunch defenders of democratic Syracuse’s independence are the oligarchs, while the Syracusean democrats sell out to the invading Athenians at every opportunity. They do so not for ideological reasons but because they hate the oligarchs.

The Athenians expect a show of force will bring Syracuse to its collective knees, and are mildly surprised by the resistance, but they remain confident that Sparta will not act. Though Nikias is less confident about this than his associates. Indeed he is so very cautious that he does not want to risk a battle for the gods can be fickle and his army is a long way from home, so he set about winning local allies on the island, establishing a supply base and so on. Time passes with small skirmishes.

Then comes Gylippus. There is a marvellous scene where the Athenians are marching around the walls of Syracuse in a demonstration of shock and awe when they encounter in a field a battle-line of hoplites standing at rest. The raw Syracuseans do not stand easy. When they lined up for a battle earlier, they fidgeted, wavered, squirmed, twisted, turned, and all but ran long before the fighting started. Not so on this day. The line is firm.

The Athenian force is great and this opposing line is much less and it is near the end of the daylight. Yet these hoplites stand calm and relaxed with their shield turned side ways to the Athenians. The Athenians approach and then on command the hoplites turn the shields faces catching the last rays of the setting sun to the Athenians who then see the lambda on the shields for Laconia, or Sparta.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The shield is big enough for a man to hide behind it when the arrows fly. Together with body armour from toe to head the load on a hoplite was about thirty kilograms in battle.

The Sparta have, this time, come, about a thousand of them face this Athenian contingent of perhaps five times that number. The frisson through the Athenian ranks is electric. Spartans! Darkness falls and no battle is joined but the news travels fast and by sunset everyone knows the Spartans have come.

Game on. Over the next three years there is much cat-and-mouse between the protagonists, each undermined by rivals there and back home. Both Nikias and Gylippus have a two-front war, one military the other is a double political one with their respective home cities and local allies.

While Gylippus did not come quite alone, he came with only a token force compared to the forty thousand in the Athenian expedition. He relied on the defensive walls of the city and concentrated on cutting Athenians supply lines and stealing silver from them so they could pay the mercenaries that comprised the bulk of their forces.

Nikias was often infirm but he was not permitted by the demos to resign and he dared not leave on his own initiative for the demos had more than one unsuccessful general put to death, sometimes along with a few relatives to drive the point home. Likewise Gylippus, frustrated as he is by his reluctant allies in Syracuse, cannot go home without a victory.

The use Hermocrates makes of the two escapees from Melos is cleverly done by the writer. The exposition of the divisions within Syracuse are well set out though the Athenian sympathisers are largely cardboard. The author leaves aside the larger question that confuses modern readers, how could democratic Athens attack democratic Syracuse. The answer is, of course, that Athens by this time would eat anything. Even as this expedition was launched there was talk of Carthage, then but a legend.

The writer’s wit, insight, sympathy for the principal characters and the way he interprets the facts recorded by Thucydides is wonderful.

Jon Martin

Jon Martin

Clearly he has walked over all the ground he describes and done so with a sponge in his mind soaking it all up. I read his ‘Shades of Artemis’ (2004) about Brasidas some years ago and found it fine, too.

‘Destination Space’ (1959)

4.9 from a measly 46 opinionators

An earnest portrayal of the political, social, and technical challenges of space exploration two years after Sputnik. The Cold War backdrop is there in the frequently mentioned enemies.

In the foreground is a massive space station wheel serving as a base for Moon exploration and landing with a view of colonising for purposes not specified, but to get there before the enemy does. Here as in many space ship films the underlying cinematic conventions come from submarine movies.

The technical problems of space travel are many but mercifully the Geordie-Speak is kept to a minimum. The social problems are surfaced. There are jealousies among the space station crew. The long stints there undermine normal life on earth. But the major problem is politics, the securing of ever more appropriations from Congress. Nothing is cheap in space and Amazon Prime does not deliver there (or here).

A qualification is in order before continuing. This 51 minute film was the pilot for television series and one assumes the other issues would be played out in future episodes. In contrast ‘Project Moonbase’ (1953) started as a television pilot and was converted to a movie, with the result that it is neither an episode nor a movie.

The bulk of this episode is the aftermath of a meteor strike on the station. What would script writers of space Sy Fy do without meteors arriving on cue? Some of the reaction is technical, fix it, and some social, get over it. But the major result is political, going back to Congress for more money.

The big scenes are courtroom-like committee testimony which is well done but which is more Perry Mason than Flash Gordon. The opposition wants to scrap the money pit that the space station is and blast multi-stage rockets straight from Florida’s Cape Canaveral to the Moon to get there before The Enemy. That would be like launching the D-Day invasion of Normandy from New Jersey, though no one says that. But then the American invasion of North Africa in 1942 was launched from Virginia.

Perhaps the best scene involves a visiting scientist come to the station to have a look, being confronted with a leap of faith into space to move from the commuter rocket to the wheel. The look on The Chief’s face was superb as was the crocodile smile Townes gave him before pushing off the ramp into the void. It is The Chief from ‘Get Smart.’ This effect and many others were well done but they came from that mishmash known as ‘Conquest of Space’ (1955).

At the end we are left uncertain of the outcome, but the characters have been established, the station, the Moon mission, the protagonists on Earth, and so on. The outcome of course was ‘No Sale’ and so no more.

Though John Agar is there, his part in this episode is small indeed. That surprised me since I supposed he would star. Rather Harry Townes leads the cast in camera time, and he does it well but he is no leading man.

He was a well travelled television character actor with a long string of forgettable credits and an Alabama accent where he was an Episcopal preacher between takes. He had gone north to Columbia University where he caught the acting bug. He certainly could act and here he twitches with nervous energy and delivers his testimony with conviction. Yet I could not see him attracting an audience with his earnest admonitions. Neither did the network buyers.

John Agar by contrast had worked for John Ford in the Cavalry Trilogy with John Wayne and married Shirley Temple. He was definitely on the A list of celebrities.

But came the fall. Temple divorced him citing alcohol, and he proved her right by finding the bottom of many more bottles, and spending months in jail on drunk driving charges. He made a comeback of sorts in B movies, especially Sy Fy and creature features and then television. But the drunk driving recurred.

The comparison must be Star Trek in 1966 where the Earth is left behind for space in a clean break. In ‘Destination Space’ the crew are all Americans and all are in Airforce coverall uniforms with the exception of the scientists who wear suits and ties to space. The crew is entirely masculine, and no women appeared on the space station, thus depriving the script writer the opportunity for the stupid sexist remarks prevalent at the time.

Absent are any women. Absent are the futuristic fashions of Star Trek. Absent are the multi-national and poly-ethnic crew. Absent is a united Earth. Absent is the alien Mr Spock. Absent is much technology, clipboards and pencils are in use. Though no one seemed to smoke on the space station. Absent is a dynamic leader, for Townes plays the committee man to a T but that is all. Absent also is any humour; no Bones to bring things down to the ground, though there is by-play among the crew that lightens the load a little, though it sounds like something the writer heard others say, and is so stale in the re-telling.

Most of all, absent is any sense of adventure or wonder at space and the cosmos. By the way, Harry Townes appeared in ‘Star Trek: Original Series’ as Reger in ‘Return of the Archons’ where he announced the Red Hour! Strong stuff that.

The fashions may seem out of place in the list above but the fashions alerted one and all that ‘Star Trek’ had left our time and place. Ditto the technology of coloured lights, automatic doors, tri-corders, and the medical scanners. Taken together these two dimensions helps convey the distance, the break between 1965 and this world of the stars.

‘The Invisible Man Returns’ (1940)

The second in the Universal franchise after ‘The Invisible Man’ (1933). In the intervening years the magic of special effects improved and those that moved slowly and awkwardly in 1933 flow nicely in this one, e.g., the telephone in the air.

Pedants will note that the Invisible Man played by Claude Rains died at the end of eponymous film, and seven years later his cadaver must have been in no fit state to return. But Universal had paid H.G. Wells for the right make five films, though corporate memory failed until 1940, and a return on investment was to be had. Voilà! Put the scriptwriter to work. On that hack more below.

What we have then is a new invisible man. This one is the brother of the deceased Claude, who in death is portrayed as a nice guy. The scriptwriter evidently neither read Wells’s book nor saw the first movie. Claude became a right bastard from the get-go and the drugs that made him invisible only made him even worse. He was vindictive, small-minded, thin-skinned, vitriolic, inhuman, and cruel. Sound like any Twits-in-Chief? Readers and viewers were all glad when he snuffed it.

But history is written by the survivors in the first instance, before the revisionists make careers out of muddling things up. In retrospect Claude is portrayed as the victim of the drugs, ahem, which he himself developed specifically for the purpose of terrifying others. Some nice guy.

Anyway he is in misty hindsight much missed and it has been concluded, again by those unencumbered with knowledge of the novel or film, that his brother did him in, and this hapless brother has been tried and found guilty and is about to be hanged. Meanwhile the brother’s chaste fiancee frets and his stalwart friend, the doctor, tinkers in the lab. This doc has a nurse but no patients and so, like Batman, is always ready to hand.

While in the early going there are many references to brother Geoffrey, he remains unseen in the slammer.

Spoiler.

On a visit to the slammer Doc slips Jeff some invisibility juice and he does a bunk in the nude. An invisible man hunt ensures and some of it is brilliantly done, as when his ghostly outline appears in the rain or amid the cigar smoke of the detective in charge, who is avuncular and unhurried about the pursuit of a convicted murderer.

Of course Geoffrey was framed and the three try to uncover the real culprit who is before their very eyes and quite visible to us all because he is top billed. But now invisible Geoffrey develops a Trump-complex and starts to rant about world domination seemingly having forgotten his own situation. He blames Hillary for everything. Meaningful glances are exchanged by chaste fiancee and stalwart Doc.

With Jeff on the loose the careful façade of the real villain crumbles and justice wills out, as it does in cinema. There is a terrific fight scene at the colliery and Geoffrey is near death. However Doc finds treating his wounds is difficult since…. he is still invisible. But the blood he has lost is evident.

Invisible or not, Geoffrey needs blood so Doc does a transfusion. Whoa. How did he find the right spot. When I go the Red Cross that is not always easy. Sometimes impossible. Quibble. Quibble. Quibble. Anyway the transfusion works and the new blood brings Geoffrey back to the land of the visibles, and low and behold it is none other than Vincent Price! He appears only in the last scene.

First to reappear at the arteries with the new blood, then the skeleton and then the man himself.

First to reappear at the arteries with the new blood, then the skeleton and then the man himself.

Earlier on the run Geoffrey dons the clothes of a scarecrow in an amusing scene that took hours to film, but seems effortless on the screen.

Like Claude Rains, Price was cast for his mellifluous voice and crisp diction, since the voice alone has to carry the leading role. His work is superlative from the resigned prisoner to the disturbed invisible to the lovesick man to the gloating would-be tyrant.

Surprising enough the effects were not special enough for an Academy Award. Beaten instead by the flying carpet in ‘The Thief of Bagdad’ (1940).

The director was Joe May, an expatriate German who fled the Vaterland in 1933, and who, despite his name, never learned a word of English and who is said to have had the dictatorial manner of his mentor Fritz Lang which earned him many enemies and ended his career. The scriptwriter who bridged the gap from the first film was the redoubtable Kurt Siodmak who gave us Wolfman and much else in Sy Fy and creature features.

‘Non-Stop New York’ (1937)

Just the facts: 1 hr 7 m and IMDB 6.9/200

Janne Wass includes it in his blog ‘Scifist, a history of science fiction movies in reviews,’ and so I had a look on You_Tube. Such is the Finn’s influence.

Janne Wass

Janne Wass

The film is a conventional krimi set in an airplane. The players are fine but the script is neither fish nor fowl, but more of a homophone of the latter. The villain is so flamboyant even the naive boy spots him long before the dense and dull copper does. The shyster blackmailer is too stupid to live. Sometimes it played for laughs, hearts and flowers at other times, and deadly drama, and back and forth.

Another case of the lobby card bearing no relationship to anything in the movie.

As to its credentials as Sy Fy, it was made in the USA in 1937 but is set in the distant year of 1938. No, that will not make the cut. After much dithering in the first half, the second half all takes place on a giant airplane that flies from London to New York, non-stop! In eighteen hours! Non-stop! Gasp!

That seems to be it.

The size of the craft is enormous and the non-stop flight over the Atlantic, these get it on the SciFist list. In 1937 that would have been phenomenal because Trans-Atlantic flight was still for daredevils. Most flights were by flying boat aircraft taking off from the waters of western Ireland and landing in Newfoundland. The alternative route, again by flying boat, was to go south through Lisbon, the Azores, Bermuda, and so on. Straight across from London to New York City only came with jet engines in 1958 when the British Overseas Airways Corporation, as British Airways was then called, flew did it. The route was over the northern most North Atlantic to Gander in Newfoundland where the aircraft stopped for fuel, catering, and relief. I once laid up there for a few hours because of weather. I cannot find a time given for these trips in 1958 but they were not non-stop even twenty years after this film.

Today the British Airways web site gives 8 1/2 hours from London to New York City. It is 7 1/2 back to London thanks to the winds. Both of these flights are direct. Singapore to New York City is more than 18 1/2 hours these days. Imagine sitting next so some fool bellowing into a mobile phone for that flight.

Let’s call the aircraft Titan, a flying boat, too; inside it is even bigger than the Tardis. The staterooms put those of ocean liners portrayed on film at the time to shame. The windows are far bigger than those that brought the Constellations down. And, get this, there are open air balconies frequented by the passengers as it wings over the North Atlantic. The baggage hold is cavernous and largely devoid of bags. There is more than one dining room. There are multiple decks and if that is not enough room our hero has to climb outside over the top of the speeding aircraft to enter the cockpit, because its doors only open from the inside. While we can appreciate this limitation as a security measure, it begs the question of how the pilots get in.

Considering that context, ‘Non-Stop New York’ is certainly futuristic in its background, but….. [quibble alert] still not Sy Fy. That futurism contributes nothing to the plot which is an unsolved crime, a missing witness, young police officer meets young woman, etc. It just so happens that the resolution is on the Titan. It could as well have been on a ship, in mountain hotel, on a lake. The futuristic element is incidental background. Harrumph. No outer space, no science of any kind, no aliens, no superwomen, none of the usual Sy Fy suspects.

The heroine, Anna Lee, is feisty, independent minded, and smart. She knows what to do and does it.

The stowaway strides up the gangway to board the airship.

The stowaway strides up the gangway to board the airship.

There were a few such celluloid female role models in the 1930s but they evaporated from the screen by the homogenous 1950s. Lee had top billing on the poster and cards of the time and carries the picture.

The story is confused and confusing and tries to slip a ninety-minute feature into an hour. It starts in New York City, then the heroine travels by boat home to England, then back to New York City as a stowaway in the aforementioned Titan. It ends somewhere over Newfoundland. All this to’ing and fro’ing reveals all too clearly the mini-budget. The New York City sets look just like the London ones and vice versa. The whole dynamic rests on the idea that in those pre-NRA days a gangland slaying in New York City is world news, and there are many spinning newspaper headlines from around the world. Some in foreign languages. Wow!

There are some good laughs and some good lines but they do not zing in the spongy morass.

By the way it is derived from a novel by Australian Ken Attiwill and one of the players later emigrated to Australia, namely Desmond Tester, who is the youthful comic relief in this tale. Tester made a career in children’s television in Australia during the 1950s and 1960s and those of certain age remember that name. He also did some Strine television drama in the 1970s. In contrast Attiwill was born in Adelaide and migrated to England. Three of his novels were filmed. As with me, there is no entry for him in either the ‘Australian Dictionary of Biography’ or ‘Wikipedia,’ but traces in the former suggest he was a journalist who married an English woman in Adelaide and went to England with her.

The saxophone playing boy Demond Tester is in the charge of his Aunt Veronica and she seemed so familiar to me, but from where? And then it came to me, as things less and less often do, from the mind palace: she was a biologist in ‘The Man-Eater of Surrey Green’ (1965) from ‘The Avengers,’ one Athene Seyler.

Athene Seyler in the 1950s.

Athene Seyler in the 1950s.

She had earlier been in ‘Build a Better Mousetrap’ (1964) where she showed the local biker gang a thing-or-two. Curmudgeonly and quirky with a lived-in face even in 1937, she was in much demand in films of the 1940s and 1950s.