My homage to Randolph Scott continues, after an hiatus. This one is near the end of the series, and the formula shows through it. Scott, as ever is a loner somewhere, sometime after the Civil War in the West. Reticent, stoic, confident, straight as the Indian arrows he dodges, here he is st age sixty-two.

A lobby poster.

A lobby poster.

His path crosses that of a damsel in distress, and she finds the enigmatic Scott compelling, yet he a distant and perfect gentleman and she, usually, is another man’s wife. To spice up the mix there must be villains, and to the credit of these productions the chief villains are never Indians, though they are there, but other Europeans. The villains are thrown together with Scott and his charge in hostile circumstances and, in this case, they have to cooperate to avoid the Indians, but we all know a showdown is coming at about minute 70. We all know who will prevail, but the skill of the writer and director still manage surprises through the supporting players like the damsel and the naif.

Inevitably, the naif grows to admire Scott and the naif’s commitment of the Villain-in-Chief wobbles. Inevitably, the damsel misunderstands Scott’s motives and only gradually sees through that misconception to his noble core. Thus there are several nested stories. The overarching narrative is to survive the hostile circumstances and return to a town. Within that we have the menace and final confrontation with nemesis. Nested still more are the doubts of the naif and also the dawning realisation of the damsel that Scott is a knight without armour. When all these themes have played out, inevitably Scott rides off alone. Oh, and inevitably Scott wears a neckerchief. Don’t know why. To hide a scar?

Another credit to the production is that the villain has personality, and is not just the CGI cipher villain now in Hollywood productions. In this tale the villain is Claude Akins, who combines a rude charm with a bottomless evil.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

The protagonist and antagonist discuss their differences.

I was disappointed to see Akins’s name in the credits when it rolled off ‘Daily Motion,’ the website from which I streamed it, because I remember the caricatures he used to play on television in the 1950s and 1960s but here he projects a distinct individual who is not all bad and yet is – in a different sense – all bad. He is aided in his villainy by the ever reliable Skip Homeier, who is knocked off too early for this connoisseur of slim-balls. The villain in this formula usually has two acolytes, and third in this party is Richard Rust, otherwise unknown to me, who is a naif who has fallen into bad company and knows no way out. The list of chief villains Scott bested in these last films is impressive, starting with the most complex, Richard Boone, Lee Marvin, Pernell Roberts, Lee Van Clef, and Warren Oates, and many others.

Indians, I mentioned Indians and they are here and on the warpath, but they are also shown to be honourable. The Comanches kept the deal they made with Scott at the outset. Moreover, that they are making war is, we learn, precipitated by the murder of many of their women and children by still other bad Europeans off camera. In fact, they are victims who are lashing out at those to hand.

Scott made at least a hundred films and perhaps eighty of them were Westerns. He got type cast but he also liked that. He rode on to the screen time after time with a self-confidence and poise born from having been through it all before, again and again. It is no wonder Sheriff Bart invokes him in ‘Blazing Saddles’ (1974).

Seven of the films Scott made at the end of his career have been the object of my veneration in this homage. Why these? Because by that stage in his career, with the astute management that made him a millionaire many times over, and too old to remain under contract to a studio, he was a free agent who could decide what he wanted to do and then do it. This he did with some long time friends and associates producer Harry Brown, director Budd Boetticher, and writer Burt Kennedy. They were made in the Alabama Hills on the east side of the Sierra Madres. Each films includes many elegiac passages as the cast travel through the area. All of them also put the life-and-death human concerns against a timeless and limitless backdrop that shows just how small those concerns are in the ultimate scheme of things.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Budd Boetticher at work.

Clint Eastwood and Martin Scorcese and others have both expressed their admiration for these films. Look for them on You Tube. It is exactly this sort of the film that George C Scott refers to in ‘They Might be Giants.’

Scott’s career culminated in one of the greatest Westerns, ‘Ride the High Country’ (1962), Sam Peckinaph’s first western, featuring a near-sighted Joel McCrea with an arthritic Scott, the ingenue Mariette Hartley, the drooling Warren Oates, and more. The gossip is that Scott and McCrea flipped a coin to see who would play which part, one a huckster and trickster and the other a pillar of unassailable integrity. Both were pitch perfect and both quit on that note. I will also sneak a peak at one of his defining films that etched itself into my prepubescent mind, ‘7th Cavalry’ (1956).

The President of the Electoral College

How is it that the USA Presidential incumbent retains the support of his voters when he acts repeatedly against their material interests?

Wake up! It is simple.

The President of the Electoral College of the United States delivers to his core supporters every day the two most important things they value. All else pales into insignificance against these two.

First, he is not a black man.

Second, he is not a woman.

End. It is primal. It is not about policy, not about politics, not about consistency, not about probity, not about government….

Politics is simple, until analysts make it complicated for their own reasons.

He also delivers to this constituency in other ways, too.

He is not an immigrant.

He does not have a foreign sounding name.

The title of this entry is taken from Vicente Fox, one-time president of Mexico, who has poked fun at Trump Donald on Facebook with more wit and zest than most others have done.

‘The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu’ (2017) by Charlie English.

The word ‘Timbuktu’ entered vernacular English in 1863 as the most distant place imaginable, according to the OED. It has had many spellings over the years but the one used here is the standard in Wikipedia. Most who have heard the word take it to be mythical, but in fact it can be found on a map, in the sub-Sahara West African nation of Mali.

Timbuktu gained some recognition among the Nerd Empire in the late 1990s for the collection of medieval and even ancient manuscripts gathered there, and more when these treasures were threatened by fundamentalists whom god had told to destroy all. Not all the nut cases are in D.C.

A building in Timbuktu.

A building in Timbuktu.

The airport at Timbuktu

The airport at Timbuktu

This book combines the Nineteenth Century story of Europeans exploring the interior of Africa to find this very place with the Twenty-First Century story of saving its aforementioned records from the flames.

The quest for this African El Dorado began in the mid-Victorian period when intrepid chaps in Britain were looking for new adventures. Africa, the dark continent, beckoned. It was called the ‘dark continent’ and ‘darkest Africa’ not because of the colour of the skin of the natives but because it was unknown, in the dark. There was plenty of racism but this term was not an instance of it at the outset. Later, yes, certainly. say as it was used in the 1950s in Disney cartoons.

In part the book traces the efforts of the African Association in London to explore, map, and study Africa, partly directed by the affable Joseph Banks, who as a young man had accompanied James Cook on his voyage to Australia, and after whom Bankstown is named, along with flora. The method this private organization took was to recruit a series of intrepid men and send them off one-at-a-time. Off they went and mostly disappeared into darkest Africa, never to be seen or heard again. Disease, dehydration, animals, sand, stupidity, accidents, villains got them one after another. Inevitably, a Société d’Afrique in Paris got into the game so that the rivalry between England and France was played out on the way to Timbuktu. Then came the Germans looking for that fabled place in the sun.

On the other hand is the story of the threat posed by fundamentalists, which is told in the choppy and breathless manner that distinguishes contemporary journalism. It is a sandstorm of names and places that mean nothing to this reader, and at no point is there an orderly exposition of what the manuscripts, papers, and documents are, how they came to be in Timbuktu, and who had formal responsibility for them. Nor is there anything more than the repeated assertion that they are valuable to justify the importance assigned to them. In the telling, it sometimes seems this town on the sand just by chance was home to a number of private collectors who had somehow gathered the written material and at other times there are references to libraries, catalogues, steel boxes, and UNESCO grants. Later there are few references that indicate that Timbuktu became a centre for learning in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, but by then I was so lost it did not help.

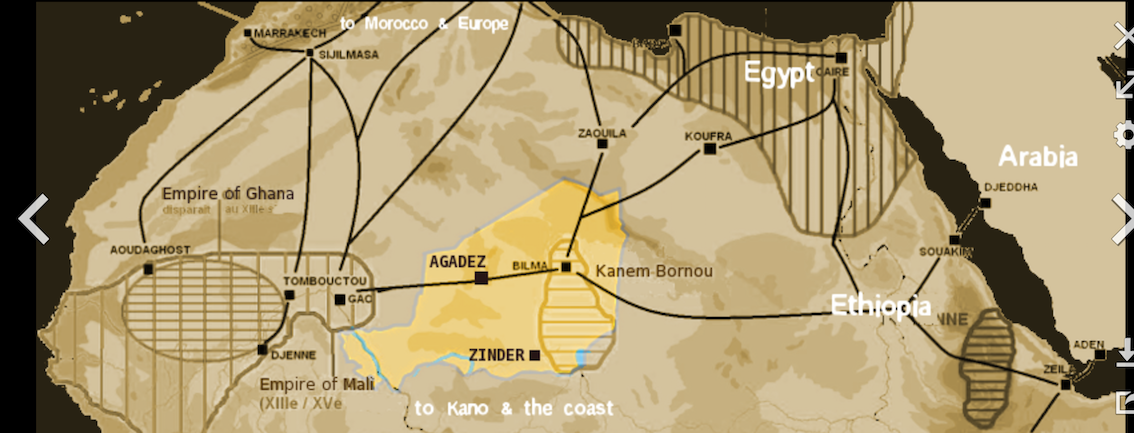

This map below from Wikipedia shows when and why Timbuktu (Tomboctou) was an important crossroads that benefitted from proximity to the mighty Niger River, from which proximity it also suffered when the river flooded. The lines are trade routes used at various times.

That combination of two stories is both an asset and a liability. It is an asset because it makes clear the importance of Timbuktu and its holdings and a liability because the author has a lot more to say about the latter story than the former and so it is unbalanced.

Trashed books in Timbuktu

Trashed books in Timbuktu

While the telling is repetitive and confusing at times, the subject is so important that I tried to persevere through all the confusion that the author reproduces.

There is a shower of proper names, descriptions of men with guns, the arrival of trucks, comings and goings as though this is a thriller. Well it is a mystery to this reader. One that remains unresolved.

Charlie English

Charlie English

I supposed the author was a journalist from the disjointed style, the disregard for readers, and the indifference to exposition, and then I checked. Sure enough. He and this book get a lot of space on the ‘Guardian’ web site. Make up your own mind. I have. With perseverance I made it about halfway through before deciding I would learn more reading Wikipedia. No doubt Good Reads is replete with fulsome comments. No doubt the dust jacket of the hardcover proclaims it a best seller. No doubt.

Dollmaker (1995) by J. Robert Janes

Inspector Hermann Kohler and Chief Inspector Jean-Louis St-Cyr, an odd couple of Occupied France, get no rest. No sooner have they nailed a culprit than a telegram arrives ordering them on an all night dash across blacked out France to another crime scene. This time it is Lorient near Saint-Nazaire. These two ports were the principle bases for German U-Boats from 1940 to 1944.

The fateful telegram came directly from Admiral Karl Dönitz, nicknamed the Lion for his mighty bellows, commander in chief of the U-Boat fleet. Dönitz became head of the government for about three weeks after the death of Adolf Hitler. The telegram was odd in that he ordered them to investigate the allegations against the Dollmaker, per the title.

It is literal, the chief suspect is a dollmaker, who is also a very successful, and still living, U-Boat commander. Toy-making was a major German business for a long time and grew especially during the Weimar period to earn export income, because there were so many restrictions of German industries and shortages of material, wooden and clay toys were made. This captain has discovered deposits of very fine clay around Lorient and dreams of reinvigorating the family business when on leave between voyages.

A very unpleasant shopkeeper has been murdered on a cold and wet winter night along a railway embankment. Left it situ, Kohler and St Cyr arrive to investigate to the great annoyance of the local gendarme commander.

The nearby stones of Carnac provide the brooding presence of eternity for the nocturnal wanderers during the long black-out nights of winter. There are thousands of stones, some to rival Stonehenge.

With the death of the shopkeeper a great deal of money also seems to be missing, the money the dollmaker raised, mostly from his crew, to invest in a dollmaking enterprise with the deceased shopkeeper. Strangely though, as Kohler and St Cyr note, no one seems now to be worried about the money.

The suspects are many. It is surprising how many people were out and about on the railway embankment at the time of the murder. There is the shopkeeper’s daughter, who was probably spying on him for her crippled mother. There is a woman married to a musician who has gone silent. She may have been looking for her husband who roams the stones at all hour to listen to their music in the wind or for a lovers’ tryst. Their daughter was probably also out there, either to spy on her hated step-mother or to find her father. Then there is that gendarme commander who seems to have left footprints in the oddest places. The U-Boat captain was certainly there and readily admits it while denying the murder. Members of the U-Boat crew may also have been on the lookout to safeguard their investment.

As usual, claims to the Resistance are made both by the Germans to explain away the murder and exonerate the captain and by suspects to hide their guilt. Kohler is indifferent to these claims and St Cyr positively bristles because he has heard this plaint often used to cloak evil. To add to the brew there is at least one Jew hiding in plain sight and a young boy may have stolen the money to bribe passage to England to join De Gaulle. Or he may be dead. The Jew has no chance. The fatalism is endemic.

Around and around Kohler and St Cyr go questioning everyone, being told repeatedly not to question anyone least the morale of the U-Boat crew be undermined or the Resistance revealed. They are threatened, harassed, misled, and lied to. All typical. The U-Boat campaign is interrupted on every clear night by RAF bombing attacks, one of which nearly kills St Cyr, while members of the Resistance are preoccupied with setting differences among themselves with weapons dropped by the British during the distractions of the bombing raids.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The well known fatality rate of U-Boats is sufficient to erode morale, and the Resistance is conspicuous by its absence in the tightly controlled area around the ports. Submarine connoisseurs will realise this is the area where ‘Das Boot’ opens.

Hardened kriminologist will have no trouble spotting the villain early on, but the interest in these stories is the trip, not the arrival. Lorient is a closed military zone rather like an island and its denizens know each other well, German and French. Kohler and St Cyr peel away the layers of lies, deceptions, half-truths to arrive at a conclusion or sorts. On the one hand it is a formulaic police procedure but on the other it is a study of humanity in such inhuman circumstances. The atmosphere that Janes draws is the chief interest to this reader.

Food is scarce, fuel nonexistent, warmth but a memory, tobacco beyond price, exhaustion general, rather than fear most people, German sailors or French civilians, are numb and weary. Yet the nightmare goes on and on.

The crew of the captain’s U-Boat have no desire to return to the depths, fearing they cannot beat the odds again, but if they must to back to sea, they certainly want the dollmaker at the helm and not a new officer, ergo he cannot go the slammer even if he killed the shopkeeper.

Before becoming a full-time writer, Janes taught high school mathematics.

‘Death of an Owl’ (2016) by Paul Torday

A tragedy might be a better genre for this novel. It turns on the accidental death of an owl on a lane in the English countryside. The vehicle that struck the owl had four occupants and their reactions to the death are the centre of the book.

There is the usual backstory about the two male principals in the car; they were acquainted in their university days. The women are accorded less space though one is developed into a formidable character who has a more clear insight that either of the men. Much of the early part of the book reminded me of ‘Brideshead.’

The tragedy is that the accident leads to the downfall of the putative leader of the British Conservative Party, poised to become Prime Minister. When a character’s demise is the result of his own personality, it is tragedy, and that applies here.

Though what we readers are to make of Andrew Landford never became clear to me, and maybe it was not clear to the author either. In word and deed, until Landford became desperate beyond reason, he never put a foot wrong, yet there are hints, mostly from his one-time girlfriend that he has a dark side, the reader only sees that at the brief minutes of the death of the owl. As we see him he is sincere, forward-looking, open-minded, and the best man for the job, a Tory Tony Blair.

The story is told by one of his campaign advisors who gets caught up in first in the cover up and then the exposure. It is well written and is credible about the political machinations at Westminster as far as this reader could tell. There are some very nice portraits of other characters in this strange world.

There are some creaks in the plotting. while much is made of the police investigation into the death of the owl, it being a member of a protected species, the two women in the car at the time of the accident are not interviewed by the police. That oversight would never happen in Midsomer!

When I hesitated about the genre for this novel, one of the reasons is because the owls have mystical presence throughout. But there is a crime and a police investigation, slipshod, though it is and so I put in the krimi class.

Finally, I found the denouement with the caretakers to be deus ex machina.

Paul Torday

Paul Torday

Perhaps the simple explanation for most of my quibbles is that the novel was unfinished at the author’s death and he did not complete it, that was done by another.

I read this book more than a month ago but time and tide have kept me from writing up my thoughts until now. I chose it because of the intriguing summary on Amazon and the reference to Minerva.

The Cartesian Method

Preparing for the Best and Brightest event reminded me once again of René Descartes and his method.

‘The Eloquent Scribe’ (2016) by T. Lee Harris.

The book is a police procedural set in Pharaoh’s Egypt. There are several krimis of this ilk but ‘The Eloquent Scribe’ has a twist in the tail, namely, that the odd couple of investigators includes a cat. It may sound contrived, well it is, but in this case it works.

Sitehuti is a junior scribe still learning his cartouches. A mishap precludes a senior scribe from attending to the dictation of a High Priest. Because he is a lazy sod, Sitehuti is sent in his place to get him off his backside. Reluctantly, he goes…into another world, one of riches, dazzling scents, blinding reflections from gold and silver and mirrored bronze, a stillness that is both solemn and eerie after the cacophony of the market place that Sitehuti is accustomed to hearing, and … cats. His sense are overwhelmed by the temple.

The scribe is seated in this group from a pyramid.

The scribe is seated in this group from a pyramid.

While the priests run the temple there is one very large, very leonine cat in attendance, one Nefer-Djenou-Bastet This sacred beast instantly takes a liking to Sitehuti, and this marks him out. It is an omen that sets tongues to wagging far and wide. Given this omen, Sitehutie becomes the scribe of choice for the highest of high priests in the innermost of inner sancta.

The Egyptian Mau cat.

The Egyptian Mau cat.

That name Nefer-Djenou-Bastet is a mouthful and it quickly become Neffi.

When a messenger bearing a most secret letter disappears along with the letter, who better to find him and the letter than a man-child favoured by the gods, well, by Neffi the chief cat of the temple of Bastet? Indeed.

Sitehuti is none to sure about any of this but it beats smearing cartouches, pounding shells into ink, or scraping papyri clean for reuse, so he sets out. Slowly it dawns on him that he might have been chosen for mundane rather than divine reasons, (1) because he is an outsider and perhaps this was an inside job — so who can he trust and (2) as a lowly junior scribe he is expendable despite the favour of Neffi for who knows how long that favour will last. What Neffi gives, Neffi can take away.

What a colourful world it is in Memphis, the one in Egypt not Tennessee, and Thebes, the one in Egypt not Greece. There are Nubians, Syrians, Hittites, Caldeans, Gauvians, Babylonians, Ethiopians, and even a Phoenician or two among the Egyptians. Dancing girls, jugglers, strong men, freakish dwarfs, bear baiters, snake charmers, and…. did I mention dancing girls? Sitehuti is a normal young man.

The other pharaonic krimis I have read were, by comparison, laboured with stilted speech which I guess was meant to reflect the formalities of the time and place and packed with equally stiff social conventions which again I guess was to reflect this ancient and foreign world. They also made tedious reading.

This novel is much more salty. There are nicknames, slang, greasy food, dusty roads, sour wine, and grumbling in the ranks, with an incipient tax payers revolt against those priests who keep collecting tribute in the name of gods but those gods who never seem to deliver for the common people. The result is a lively journey.

It is a police procedural in that Sitehuti goes hither and thither asking questions and looking around gathering information, impressions, and even physical evidence while Neffi guards his back clawing off more than one thug and generally putting an aura about Sitehuti, who while grateful for the help, is not sure he likes being so special that the dancing girls venerate him at a distance rather than coming closer!

T. Lee Harris and friend

T. Lee Harris and friend

This is the first is a series with several other novels and short stories. By the way I cannot connect the title to anything in the story.

‘The Best Years of Our Lives’ 1946

The other day by accident I came across a reference to this film somewhere or other, and much of it came back in a rush. That is a tribute to director William Wyler who got a performance of a career out of the block of wood known as Dana Andrews. A screenplay by that remarkable wordsmith Robert Sherwood is understated. and often pensive. There is much that is not said because it cannot be said. But it weighs on each of the three principle characters, Fredric March, Dana Andrews, and Harold Russell.

That jolly upbeat title belies a taxing story which I doubt I would have the fibre to watch today.

Then there is this jolly lobby poster which in no way prepared audiences for what they were to see.

Then there is this jolly lobby poster which in no way prepared audiences for what they were to see.

These three Odysseuses survived to return when so many others just like them did not, an indelible fact each carries everyday; moreover they return to a new and different world. They have changed and the world has changed, too. The three Penelopes have also changed, and that enters the equation.

Every viewer will remember Homer (Harold Russell) and so we should. How daring Wyler was to cast a paraplegic to play a paraplegic. It broke the unwritten law of Hollywood of showing reality.

Harold Russell

Harold Russell

Even more daring was Sherwood putting the word ‘divorce’ in Fredric March’s dialogue. At the time and place it was simply not a word said in public. That word was the reason the film was not shown in some places. Perhaps the supposition was that to hear the word ‘divorce’ would drive couples into divorce.

The ghosts are many and mighty that overtake Dana Andrews. Andrews, in a long subsequent career, much of it in B-movies, never equalled his portrayal of confusion, consternation, and dread, no shouting, no hysterics but driven deep none the less. That scene when he once again sits in that seat is indelible.

Andrews driven deep within himself.

Andrews driven deep within himself.

Perhaps that was Wyler’s genius, to have an actor who would not over do it. But just let it happen. It happened.

If this is too cryptic, Mortimer, watch it. Those who have seen it, they will remember it well. Those who have not, have an experience in store that has no equal in contemporary cinema.

Robert Ryan, ‘A Study in Murder’ (2015)

The third in the series that I have been gulping down, one after another, ‘A Study in Murder’ once again plunges the hapless Dr John Watson, late of 221B Baker Street, into the thick of a villainous plot. Mrs Gregson is there to throw a lifeline, and the decrepit Sherlock Holmes has resources of his own to apply. The redoubtable Sie Wölfe, Ilse Brandt, continues her savage rampage. Her bodycount must have reached double figures by the end of this page-turner.

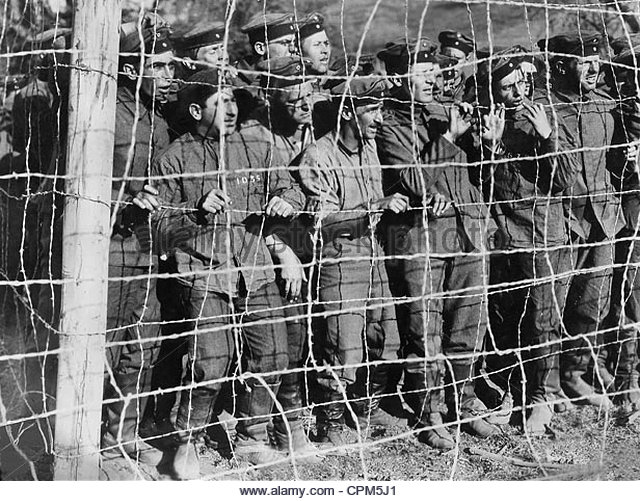

At the end of the previous volume, Watson was injured in the explosion of a tank along the Somme. He awakens to discover he has become a prisoner of war deep in the Harz Mountains. The lager is one that is hidden from the Red Cross and all manner of unsavoury things occur there. While the German regime is harsh, Watson comes to suspect the prisoners themselves are worse than the warders, English gentlemen though they may be.

The Harz Mountains

The Harz Mountains

How Watson, a geriatric, finds himself in such pickles is due to the ingenuity of the author who shows him no mercy.

Mrs (Georgina) Gregson contrives a fantastic plan to free Watson. Meanwhile, his life is made even worse by the machinations of an old enemy with a long memory who now works in German counter-intelligence. The plot is very thick. Gregson makes a tenuous alliance with Ilse, Mycroft Holmes, an MI5 man who lusts after her body, a music-hall magician, the pilot of a barrage balloon, and a cadaver. Yep. The dead can help, maybe that should have been the title here.

Holmes, they suppose, is too far gone to know or care what is happening. (Ha!)

In addition, another squad makes use of a German sniper to clinch the deal. There are many chefs in this kitchen, none with a recipe.

Meanwhile, the detective in Watson keeps following clues in the lager through cold, snow, drafts, coffins, tunnels, and hunger of the prison camp to discover…. Wheels within wheels within wheels.

POWs in world War I

POWs in world War I

For a man of his years, Watson has remarkable recuperative powers given all the stresses and strains the author deals out to him. He is struck with a rifle butt, hit over the head with timber, pushed down holes, punched in the gut, and shot, all while living on 1200 calories a day in winter, and he keeps on keeping on. What is his secret?

With each turn of the page the brew is deeper and darker, the mix is richer and more varied. There are so many incidents and characters that sometimes the book is hard to follow. It seems to be two (or more) novels plaited together.

To this reader loose ends remained, chiefly whether Captain Brevette did indeed make contact.

Ryan is a prolific writer and has turned out a nineteen novels, four in this Watson set, as listed in the Wikipedia entry. I hope he sticks with Watson for a while longer.

When I read these, the Watson that comes to my mind is that played by David Burke in the series featuring Jeremy Brett. Note that this series was split, and two actors played Watson. Burke played him as young and more physical than most do.

The quintessential Dr John H Watson of Baker Street is, of course, Nigel Bruce. His Watson is avuncular, warm, fun-loving, roly-poly, friendly as a puppy, dopey, stalwart, bluff, predictable, banal, talkative, superficial and he went a long way to restoring Watson to the Holmes cinematic canon. That is, earlier film adaptations of Holmes stories had diminished and sometimes omitted Watson. By the way the ‘H’ stands for Hamish.

Nigel Bruce

Nigel Bruce

Moreover, Bruce’s Watson also represented the perfect foil for the quintessential Sherlock Holmes, Basil Rathbone. This Holmes is mercurial, incisive, cloaked, impatient, spare even sour, mince, cryptic uncommunicative, mysterious, and razor sharp. They partnered in fourteen films, ending only when the executive producer died, leaving no one else to champion the franchise, which in truth was tiring. The directing and acting had remained pitch perfect, but the stories, despite the oeuvre available, had became hackneyed in the effort to give them contemporary settings in the 1940s.

Nigel Bruce was the second son of a baron. But he was stage-struck as a youth and foreswore the life of the landed gentry for the theatre. He was an infantry officer in the Great War and suffered eleven gunshot wounds at Cambrai (Northern France) in November 1917. Those wounds ended any later army career. By the way, British tanks were deployed in this battle but in dribs and drabs as mobile block houses, not as a strike force.

I met Basil Rathbone at a poetry reading and I was an undergraduate in 1966.

Robert Ryan, ‘The Sign of Fear’ (2016)

Once again Dr John Watson, a serving major in the Royal Army Medical Corps, is thrust, unwillingly, into action. This time the setting is London, a London that is under siege in 1917.

Everything is in short supply — food, medicine, clothes, manpower — as the U-Boat stranglehold tightens, cutting off supplies of everything.

Moreover, the city is being bombed, first by Zeppelins, but when they proved too fragile and hard to handle, there was a technology leap to the long range bomber, Gothas and Giants. These aircraft operated from Belgium. They flew higher than the rudimentary anti-aircraft guns could reach, and higher than the Royal Flying Corps pursuit planes could climb, and so the bombers came day and night when the weather permitted.

The Zeppelin were so unreliable that at least one raid bombed Hull in the belief it was London. Consult a map to see the magnitude of the navigational error.

A Zeppelin over London.

A Zeppelin over London.

Meanwhile, the privations killed the weak and vulnerable, sapped the energy of all, and depressed many. The bombs were few by subsequent standards, but they terrified one and all and paralysed the populace far beyond their destructive power. Per Wikipedia there were eighty air raids and add to that the false alarms.

It was the world of war that H. G. Wells had imagined, waged by machine. This bombing experience goes a good way to explaining the focus on airpower in the inter-war period.

In such a brew there were rumours of still other weapons to come, like canisters to drop poison gas or diseases, like giant cannons to bombard England from the continent, like …. As always these wild speculations were promoted by the press.

Amid all of this hysteria, Dr Watson finds himself drawn into a terrible nexus. There are anti-conscription plotters, the incipient Irish Republican Army, and German spies and saboteurs, along with criminals, each hard and work and perhaps in some kind of alliance. Added to that are the machinations of MI5, as the counter-intelligence agency, which seems even more sinister, if polite and civil in person. The defence of the realm (DORA) seems to justify anything and everything.

Then it gets worse. All members of an important war committee go missing in one night! Watson, as his luck would have it, is the last person to have seen one of them…alive.

Once again Watson is battered and bruised, and barely able to walk, but walk he does: into another trap. He even takes to the air in more than one way.

Ryan’s evocation of 1917 London under siege is very well done, and much of it an eye-opener to this reader, leading me to consult many Wikipedia entries for a start I had always thought that the bombing in the Great War was a few explosives dropped by wandering Zeppelins. There was much more to it.

There are many loose ends in this title, as with the earlier ones. It is by no means clear to this reader that the plotters were working alone or in tandem, the death of Ilse Brandt is muddled, why was the captain arrested at the end, did Watson land safely or not… While the opening haste is explained at the end, it begs one principal question, why did that captain allow the nurse on board if he knew what was to happen, and if he did not, why was he culpable.

It ends abruptly as though time was called not because resolution had been achieved.

In 1917 with its own resources, including civilian morale, wearing down, despite the closure of the Eastern Front, the German war cabinet gambled on a throw of the dice to drive England to the table before the United States entered the war.* The conclusion had been reached in Berlin that the United States would sooner rather than later enter the war on the British side. To preempt that entrance, the decision was to do everything possible to drive Britain to terms, if not surrender. Seeing no way to break the stalemate on the Western Front, other fronts had to be enhanced: espionage, and the sea and the air.

The chief result of this decision was the official declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. No ship would be safe, neutral, unarmed, far away, or bearing Red Cross markings, all would be targets. The calculus was that a denial of supplies would starve England into submission before the Yanks arrived.

This much can be found in most detailed histories of the conflict. As often is the case the direction of casual arrows is by no means clear, because the advent of explicit and authorised unrestricted submarine attacks is the very matter that prompted President Woodrow Wilson’s reluctant move to war and convinced and the even more reluctant Congress to concur. One could say that the German decision produced the very result it had been intended to avert.

What was new to me was the accompanying bombing campaign which was partly aimed at the shipping infrastructure on the docklands, but since the accuracy of the attacks was, well, there was no accuracy, and so the effective target was the city of London, though other ports like Southampton were also hit, sometimes by accident or mistake as Hull above.

In both submarines and bombers, the Germans had for a time technical superiority over the counter-measures.

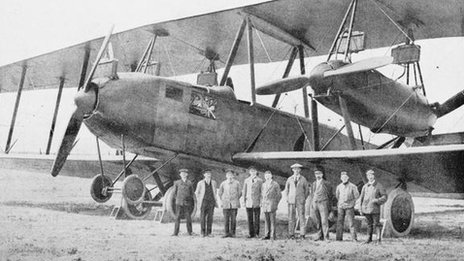

One of about eighty Giant bombers that operated from Belgium against England.

One of about eighty Giant bombers that operated from Belgium against England.

England was the target of the bombers rather than France because the Berlin assessment was that aiding the French would not motivate public or political opinion in the United States, and if Britain could be subdued, France would follow, one way or another. Also France was much less dependent on shipping for food.

*The Eastern Front did close with the Communist coup d’état in Russia and the peace with the Soviet Union, but the turmoil there was great and continued, many, many German and Austrian troops remained engaged there in Poland, Finland, and Rumania, in particular, as warring elements battled for spoils.