A new locale, a new investigator, a new approach for this jaded reader of police procedurals.

The protagonist, Owen Irvine, was once in policing and then spent a decade investigating social benefits fraud for the local council in Cumbria.

His past in policing is murky, and no doubt more of his backstory will emerge. Ho, hum. Backstories do not a front story make.

Tracing penny-ante fraudsters is not much fun for Owen but there are challenges. Mostly though his prey are single mothers trying to squeeze a few more quid from the system for their kiddies, or so they say despite the new car in front, the satellite dish on the roof, and the ashtray full of St Tropez cigarette stubs on the table.

Owen is numb, having heard all the lamebrain excuses before, each told as if unique.

Not only does the council squeeze the pounds it pays to claimants, it also squeezes those it pays to the investigators, and the chopping block has Owen’s name on it. While his record is the best, it is too good, because he has banged up more than one relative of a councillor. In this and several other ways, the plot is leaden.

Then he meets one fraudulent claimant who is different. It is another woman, but one without excuses to offer, who seems educated, and smart, and who admits her crime, and yet …. she was desperate enough to pull a stupid stroke for a few hundred quid.

Owen breaks his own rule and asks why? He has never had to ask before. Always before he is told an avalanche of reasons he does not want to hear, because he is only serving the injunction, not making the decision. This one, Clare, tells him reluctantly a story about a man who deceived her, took advantage of her, and drained her bank account.

He passes the story onto a comrade in arms at his old nick, and, by the legerdemain of crime fiction another similar case arises, and the chase is on. Well sort of.

There a reality check in this book. Time is budgeted and for a crime without violence, for a crime where there is no evidence of a crime apart from the drained bank accounts, the time allocated is half a day. Imagine what a Star Trek film would be like if there were a Star Fleet budget. No more warp engines, Captain, we are out of dilithium crystals and do not have the gold-pressed latinum to pay for more until the end of the space-year.

Ah but the recently sacked Owen, who is more or less financially independent (because he owns his home, has a vegetable patch, a trout stream, an eternal Land Rover, and few needs), has plenty of experience in finding people who do not want to be found and time on his hands.

That is the set up. A pretty good one, if only it had been told with some élan or wit.

This reader felt the boxes being ticked. Perhaps that is inevitable in the first title of the series. Owen’s backstory is forced into the foreground. To do so makes it very wordy and slow. Though Owen is supposed to be laconic and reserved, but he talks about himself incessantly to get that backstory out. To enhance Owen he is made a victim in the dismissal by the council and by implication in his earlier dismissal from the plod. A poor put-upon hero, yet again, martyr to his virtue. All of this background interferes with any interest in the foreground. The time and place are described but they take a distant second place, and that is a shame, because the regional setting is what I found attractive at the outset.

Among the compensations are some lively scenes. The puzzling interview with Clare is one. Another is with a fraudster who seems to have done it just for fun and enjoys discussing it with Owen. Then there is the police officer who is uninterested in the information Owen passes on. They have a pissing contest, as they say on Channel 7Mate. Predictable but well done.

Regrettably, but perhaps inevitably in this kind of context, all the characters sound alike, use the same speech mannerisms, idioms, and vocabulary. All the police officers sound alike, even the educated Asian woman. Indeed, Clare is only distinctive voice in the early going, and that is a plot device, to be sure, and a good one, but it emphasises how monotonic the rest are, including Owen.

J. J. Salkeld, a very industrious writer to judge from the array of titles on Amazon. Strength to his arm.

J. J. Salkeld, a very industrious writer to judge from the array of titles on Amazon. Strength to his arm.

It is the first in a lengthy series and perhaps things come together. Time will tell, if I get back to it. I found it easy to put aside.

‘Schrödinger’s Gat’ (2013) by Robert Kroese

A noir krimi with quantum physics!

I selected it for the Kindle because I smiled at the title on the cover. Wait! There is more. It is a krimi based on quantum physics. Yep! (It also represented light relief from reading Nietzsche.)

Huh?

That is how our protagonist reacts. ‘Huh?’ He is Paul, one very depressed loser in San Francisco whose path crosses that of Tali, who saves his life but she runs away when he tries to thank her.

A chartered loser, he is used to people avoiding him, but not quite like this. He pursues her, and, without breaking stride, she promises to explain all, but first he has to grasp some quantum physics.

Huh? Well, all right.

But before she can explain much, she first has to do a few things, and, well, seeing is believing, and Paul sees enough to … believe, a little. She arranges to met him for a further explanation but she is a no-show.

Huh? (Paul has a small vocabulary.)

What is a fellow to do but Google it; he reads up on quantum physics, advising readers in direct address to skip that part of the book. I should have, but I didn’t. Had I, that would have been in total about three-quarters of the book. Of course the cat comes up.

During this ersatz research he comes across the name of a Stanford scientist, the summaries of whose work on websites sound like Tali’s interrupted exposition. While the scientist seemed to have had a fine career strewn with publications and accolades until a few years ago when he, too, seems to have disappeared. Huh. (See!)

But even a loser can use the telephone book and Paul finds a street address that might be that of the professor. Hey, presto!

Well, that’s a lead. What would Philip Marlow do? Doh! He would go see the professor.

It is a mile-a-minute, except for the asides on matters quantum physics, and is it droll. dry as dust. Regrettably the asides on QP increase, and go on and on. The mile-a-minute stretch like a Salvador Dali watch.

Oh, and the cat. Did I mention the cat? Well, there is neither a cat nor a gat. Which word I always assumed was derived from Gattling gun, the rapid fire weapon developed in the Nineteenth Century, precursor to the machine gun. Another weapon so deadly that its inventor thought it would end war.

The set-up sounds better than it reads. It takes a quarter of the book to get the characters lined up around all the lectures on QP. There is so much preliminary fussing that it reminded of those dreadful Sunday lunches where the fussing over nothing is continuous so that the food does not appear until 4 pm by which everyone has had too much alcohol and a headache either from the drink or lack of food.

Then Paul inadvertently, if you can believe it, drops a homemade bomb into the fountain at a shopping mall and it kills a great many people. The cops arrest him and in his cell he reads Kant on metaphysics and shares it with the reader. Which is harder to swallow the bomb at the mall or Kant in the clangour? What is worse is reading it.

By this stage three-quarters of book has elapsed without any further sighting of Tali, and no explanation of events that this reader can follow. Where is that damn gat? Where is Schrödinger? Or even the cat?

Eventually this mass murderer is sprung on bail. What! Fire that DA and get one keeps capital criminals in the slammer.

There is a final confrontation of sorts but mostly it is like one of those post-modern conference presentations where the words flow but the meaning does not. The characters talk each other to death, or something. Hard to tell through my glazed eyes. Since this is San Francisco there is an ever handy earthquake to settle matters.

There is a long afterword with more QP. Enough, already!

Robert Kroese, who has many other titles on Amazon.

Robert Kroese, who has many other titles on Amazon.

Following the afterword is a biography in which we read that the author wrote his first novel in second grade. Is this it?

I did make it to the end, but only with quick thumb work flipping the pages with very little reading and less pleasure.

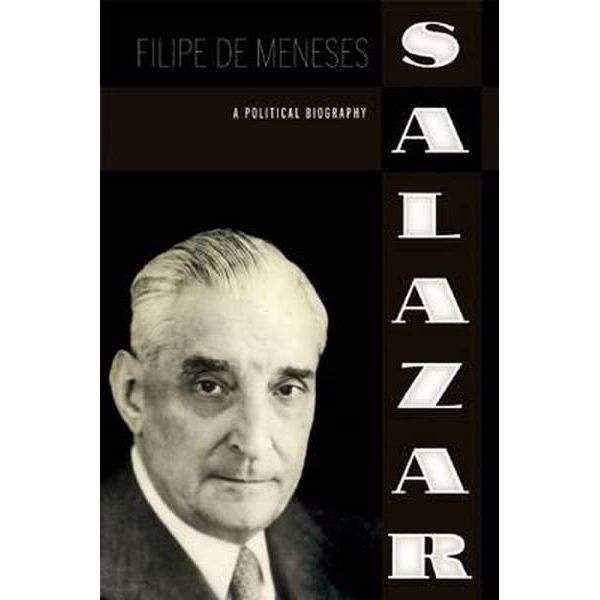

Filipe de Meneses, ‘Salazar: A political biography’ (2009)

The Salazar regime in Portugal was eternal and ephemeral. It was granite and then poof, it disappeared over night!

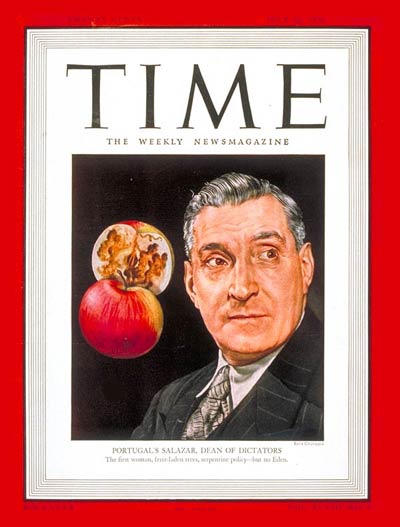

Salazar was one of the great dictators of the age of dictators and yet he was unlike any of the others of that ilk. Portugal was a fascist associate while a Western ally.

Salazar’s regime was authoritarian and yet tolerant in ways none of the other dictatorships were. Salazar’s regime looked backward and yet adapted to change. Salazar’s Portugal was a tiny country at the end of the line, more often forgotten than remembered, yet it coloured the world map with an empire that rivalled those of Great Britain and France in its extent and surpassed those of the Netherlands, Belgium and Italy in volume.

The paradoxes could be extended, but let that suffice to show what mysteries Portugal and Salazar offer.

First to some facts. António de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970) dominated Portuguese political life from 1926 to 1968. The regime he created lasted until May 1974 when winds of change blew it down.

His singularity starts with his name. In the conventions of the Iberian peninsula children take the surnames of both the mother and father and in that order. In his case, they are reversed for his father was Oliveira and Salazar his mother. There is no explanation in these pages of this oddity.

He was born in a village to a modest but prosperous family, the fifth surviving child and the only boy, who was doted on by his four sisters and his parents. They educated the girls to read and write, and him, too.

In 1900 Portugal had a population of 5.5 million, comparable to the Netherlands, Sweden, and Canada at the time, while France, Britain, and Germany were 40 million or more.

In 1415 Ultramar Português became the first European empire to span the globe; it began with Ceuta (later ceded to Spain) in North Africa. In 2017 the territories that were once part of the Empire lie in sixty different sovereign states! (Well, so says our author but I could not verify that figure by examining entries in Wikipedia.) Vast and diverse.

Of course not only had Ceuta been lost by Salazar’s day, but also Ceylon and Brazil. Gone these lands were, but not forgotten, especially the latter.

The geographic imperative had at times pushed Portugal into the arms of Spain and at other times the impulse for independence drove it away from Spain. The rivalry had something of that of a little brother and a big brother, with the difference that the identity of each changed. Sometimes Portugal was the big brother, and at other time the little brother as the fortunes of the two countries waned and waxed in changing circumstances.

In facing the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal has long been a major trading partner with the dominant sea-power of those northern waters, England. In 1373 it entered into a treaty of perpetual friendship with King Edward III of England, signed by Queen Eleanor of Portugal, and that treaty played a part in Salazar’s life and times and remains extant to this day, and is sometimes referred to as the Port Treaty, not short for Portugal but to refer to the beverage port, which derives its name from Oporto from which much of it has long been shipped.

Back to Salazar, as a boy he was precocious and shone in his early school work and did well in national examinations. The only way to continue his education was through a seminary and off he went. The default assumption was that a boy in a seminary would continue in the church. He did not.

His devotion to the Roman Catholic god was complete and, it seems, never questioned, but the wider world called to him, and again through national examinations he won a place at the historic Coimbra University, established in 1290. It was the only university in Portugal at the time with but five hundred students, all men. Admission was entry into the elite of the small country and its vast empire and the Portuguese-speaking world beyond the empire. Among his classmates were individuals with whom he would work for the rest of his life, and some enemies, too, in the small world of Portugal.

He is routinely ranked with the dictators of the day, Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and Franco and their many lesser imitators in eastern and central Europe, like Dollfuss in Austria, Antonesçu in Romania, Horthy in Hungary, and Metaxas in Greece. Yet Salazar stands apart from these others in two simple but important ways.

He was not a military man in any sense. Try though one might, not a single picture can be found across the internet of Salazar in a uniform. None. He did not do military service as a youth, because he was a seminarian and then a university student. Nor was he ever interested in armies, weapons, uniforms, or that which comes in their train. The military played a major role in his career but he was never part of it and always distrusted it, and put considerable effort into reducing its size and influence.

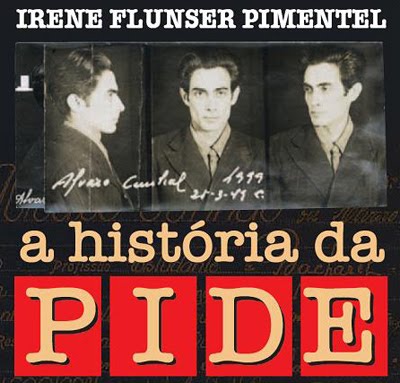

There is a second way in which he differs from this club of thugs. He spiritual commitments were palpable and sincere. Because of that religious core, he followed Christian teachings, so that he never used, abused, and discarded Portuguese on the industrial scale that the others did. Later, yes, in time there were Secret Police (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado), prisons, and censorship, but not at the outset and never on the same scale as thugs in the club.

Salazar made his regime, not with clubs and guns as Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and Franco did, but with paper. His political power grew out of the barrel of pen.

Footnote. Portugal had remained neutral at the outset of World War I. The British invoked the time-honoured treaty to protect Portuguese colonies in Africa, and there were armed clashes with German forces in Angola and Mozambique. In addition, submarine warfare off its coast alienated public opinion, especially those who traveled and shipped by sea. In 1916 the Portuguese seized German ships in port as reparations for Portuguese ships sunk by U-Boats and Germany declared war on it. About 50,000 Portuguese served on the Western Front. This force was pulverised in one day of battle with 8,000 dead and 12,000 casualties. A few thousand went to Africa where many died from disease.

There was starvation and death because of the blockade of submarine warfare, and the Spanish Flu afterwards killing thousands more. Though far from the battlefields, Portugal suffered greatly during this war, which left lasting scars which Salazar faced in his early days.

Salazar’s career began in the 1920s when a military government in extreme desperation made this professor minister of finance and he performed miracles in balancing the budget. The army made him and for years army officers toyed with unmaking him.

The military government was anti-monarchist and republican with some liberal elements that wanted to modernise Portugal.

Salazar quickly proved himself invaluable to the generals, much as they despised him. The details are well told.

Salazar at first tried to integrate Portugal into the world economy after World War I, and succeeded in balancing the budget, but he was struck by the railway car of the Great Depression. No sooner did he payoff all of Portugal’s debts and go back on the gold standard than the bottom fell out of the world economy.

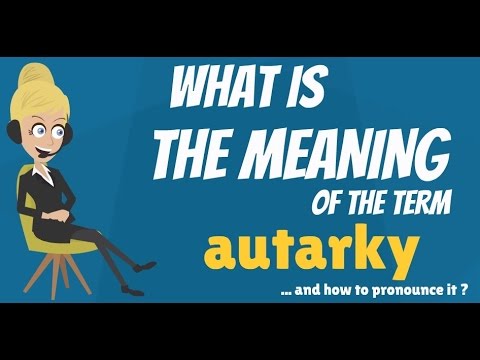

Salazar in reaction turned inward to make Portugal an autarky. (Look it up, Mortimer.)

Doing that met severe restrictions on consumption and production and these were policed. Right down to the calories. Sumptuary laws, though not called that, also reined in the consumption of the wealthy. All of these was clothed in Biblical rhetoric. While he believed in education, trains, hospitals these could only be built within a balanced budget. Better to do without them, than go into debt because in the aftermath of World War I he had seen the truth that ‘debt kills.’ (A phrase Bob Dole used at times to explain his own approach to public policy.)

At the outset Salazar took the time and made the effort to educate the newspaper-reading public in the realities of national finance, and he created a statistics office for that purpose. The constant demands for explanations, and the endless special pleading over the decades eroded his good will and by the mid-1930s he slowly turned down the authoritarian road. Gradually he replaced the military officers in government with civilians. In time he managed to assign troublesome critics to posts in distant colonies.

The biography shows this gradual shift into the authoritarian gear, slowly and surely, with some stops and starts. But always heading in that direction. He was never a democrat but he was tolerant of differences, and sometimes changed his mind.

Salazar rehearsed all the criticisms of parliamentary democracy that authoritarians and the contemporary media dish up. With revisions to the constitution, more and more authority was concentrated in his office. This process was made possible by the unflinching support he enjoyed from General António Óscar Fragoso Carmona (1869-1951), who was the president (1926-1951) and the de facto commander-in-chief of the army, against many officers who wanted to see the end of Salazar. They did not like living with the means of the country either.

Carmona

Carmona

There is little in the book about how and why this odd couple collaborated. Carmona was a soldier’s soldier but he was a free mason and a republican, while Salazar was a devout Catholic and a traditionalist, though he judged it was impossible to return to the monarchy, he did want a government above the fray, not one subject to the whim of an electorate. In early days Salazar was careful to defer to the formal authority of President Carmona. At other times, he feigned illness to show the President just how invaluable he was, and at times threatened to resign unless his wishes were realised.

In Salazar’s Portugal everything was regulated and controlled in order to live within its means and to maintain social order. To open a coffee shop, one needed permission and if there was a coffee shop nearby, permission would be denied. Put those resources to another, more productive use. There was no free market. Likewise labor became controlled with only a few government-approved unions. Slowly but surely Portugal became the so-called Estado Novo.

Part of the Estado Novo was a revived patriotism. Because most of Portugal’s recent history had been conflict, Salazar renewed interested in the heroic past of the late medieval and early renaissance periods when Portugal was a world leader in learning, in christian piety, in navigation, in the arts and architecture. He poured money into identifying, preserving, explaining, and opening up this past for the contemporary world. Buildings and books from this era survive today because of this investment.

Salazar did not delegate easily and for years nearly everything from permission to open a cafe to army promotions went over his desk. He publicly acknowledged this concentration to explain the slow pace of activities. He was not a workaholic and seems never to have been in a hurry, always on Portuguese time.

July 1946.

July 1946.

Salazar had no interest in Portugal’s empire but it remained, and threats to it from other colonists were a constant worry to some as were threats from within it, especially the resource-rich Angola, which might secede. The historic significance of the empire was too important to ignore and in time it entered into his calculations, mostly as a source of revenue or resources. Colonies that offered neither were neglected, e.g. Goa, Timor, and Macau in Asia.

Nor was Salazar much interested in the economic development of the colonies because he supposed, rightly, that the Portuguese settler population there was not loyal to Lisbon but more inclined to pursue their own interest, even to the point of going over to the British or French. While he did not value the colonies, he could not be seen as the one who lost them as they were part of the distinctive national patrimony. Many a political leader has been over this barrel.

In time Salazar subscribed to Lusotropicalism. Huh? It was a doctrine first developed by a Brazilian sociologist and one which Salazar gradually adopted more and more explicitly. Portugal was a multi-racial, pan cultural, and plural continental agglomeration of peoples. In this combination of attributes Portugal was unique. It recognised the reality that Portugal needed the colonies (for resources and prestige) more than some of them, like Angola, needed Portugal.

The term ‘Luso’ comes from the Roman name for what is now southern Portugal, Lusitania. (Yes, like the famous ship.) There is a Lusophone association today comparable to the Francophone Union.

While its longstanding treaty with England was honoured, Portugal remained neutral in World War II but with great difficulty and much manoeuvring. The Japanese encircled and starved Macau but did not set foot on it. The Dutch and Australian armies landed in Dili (Portuguese East Timor) in violation of this neutrality, and when the Japanese retaliated by entering East Timor, Lisbon made a symbolic protest but did not join the Allies and allowed the Japanese legation to stay in Lisbon. The Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde Islands were of great strategic value during the Battle of the Atlantic, like Iceland, and the British convinced Salazar to allow a base in the Azores in early 1943 but only after long, detailed, and laborious negotiations. Portugal did not participate in any aspect of this base. All the materials and labor was supplied by Britain. While this was a lost business opportunity for cash-strapped Portugal, it allowed Salazar to say to Franco and through him to Hitler that Portugal was not a party to this base but only a reluctant landlord who received no rent.

Part of the agreement with Great Britain permitted Portugal to continue to export tungsten (sometimes called wolfram) to Germany. With the income from these sales, it paid for imported food from Brazil transported on British ships. The tungsten trade is the nexus of ‘A Small Death in Lisbon,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

Antony Eden credited Salazar with restraining Franco’s Spain from a more active association with Nazi Germany. Certainly relations with Spain occupied Salazar morning, noon, and night for more than a decade. While Spain had little to contribute to the German war effort it did have one strategic asset of global significance that the Germans did want — Gibraltar.

The Rock

The Rock

It is easy to imagine that Franco with German encouragement and assistance might have besieged or even seized Gibraltar, and that would have all but closed the western Mediterranean to British shipping, and that would have been a strategic blow of monumental proportions. Without naval supplies Malta would have succumbed, freeing the Mediterranean of RAF control. Then the Afrika Corps of Erwin Rommel might have prevailed in North Africa cutting the Suez Canal and threatening, if not reaching, the oil fields of Middle East, or outflanking Russia in the Caucuses. The German General Staff had developed a plan to assault Gibraltar but the logistics to support it were impossible without the active assistance of Franco’s Spain and probably also Vichy France, both of which were neutral.

While Salazar’s government was and became increasingly authoritarian, it did not come to power, he did not come to power by violence as did Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco and the regimes they created. Nor was violence a direct instrument of government in Salazar’s Portugal. There were no purges. No systematic attacks on parts of the population, Jews, unionists, free masons, homosexuals, or others. Murder was not a policy. Even those who tried to assassinate Salazar suffered exile, not torture and murder.

There was also no general social mobilisation. Yes, Salazar repeatedly called on Portuguese to make sacrifices for the nation, but there were no rallies to create a nation figuratively, if not literally, at arms. Parades there were on patriotic anniversaries and religious festivals, but no Nuremberg rallies, no harangues from Roman balconies, no colossal vanity projects built by the slave labor of political prisoners as occurred in German, Italy, and Spain.

There was no ideology pervading the army, the bureaucracy, the police as there was in the other three. There were no Thought Police. The only test for a place in any public institution was technical competence not ideological adherence. While the communist party was outlawed, there was no systematic or sustained search to ferret out its members and sympathisers. If they kept their heads down, then that was enough.

Nor did Salazar strut like a Mussolini, suck the blood of the crowd like Hitler, nor pass death sentences with a yawn like Franco.

Likewise he had no interest in the army, which had overthrown the monarchy in the name of liberalism, and tried, as his authority increased, to circumscribe it. He seems in part to have been trapped by his own imagery of the householder who must husband resources, and he could see little use of weapons and soldiers, and so declined to spend escudos on them.

Instead he relied to England on one side and Spain on the other to secure Portugal. A risky balancing act, but far less expensive than trying to create a modern army, which realistically was never going to be able to defend the country from either Spain or England any way, and easier to control. He seldom visited army barracks, and when he did, he did not come bearing gifts. Two generations of underfunding of the army may explain why it was inept in the colonial wars.

He is never to be seen in a uniform, though some short-lived efforts were made to create organisations supporting the regime with armbands and the like, he took no interest in these and they passed. There was no Hitler Youth, no Roman Legion, no Blue Shirts, no Brown shirts, no Red shirts, no Black Shirts, no Falange, no Nazi Party. Nor were their pledges of personal loyalty to Salazar extorted from the populace.

Yet it is equally true that many suffered in his regime. There were all manner of exiles from the previous tumults, monarchists in Brazil, extreme rightists in France and later in Spain, leftists in Spain and then France, republicans in England, liberals in France, adventurers in Tangiers. His regime exiled many, by banning them from Portugal for sentences of two or more years, leaving them to go where they might. In time, concentration camps were built in Angola and then Cape Verde where political prisoners were interned in terrible conditions and more than half died of disease.

And yet, when relatives of political prisoners in Cape Verde or Angola wrote petitions to him, he read them. When relatives asked for a personal audience to plead the case for a political prisoner, sometimes he acceded and heard them out. He seldom if ever changed his mind but he read the letters, and he did listen. Little as it may seem, it is inconceivable that Hitler, Mussolini, or Franco would do even that. There are many other instances of his forbearance in other contexts, too.

During the Cold War the PIDE grew and justified its existence by finding red plotters under many beds after kicking them over.

Arrests without writs or trials, and torture occurred, along with the murder of opponents of the regime. Salazar may not have known the details but nonetheless he created the system that spawned these deeds, and he kept a blind eye turned. Salazar identified so completely with the regime that any opposition to one was a betrayal of the other and the repression grew, and as always there were willing hands to do so in PIDE. Amnesty International was born partly in response to Salazar’s Estado Novo in the 1960s.

While the corporate elements of the Estado Novo kept prices low, this simply created a black market, often operated across the Spanish border, in which some grew rich and others suffered. When the colonial wars came it was the same story. Those from well off families did not go Africa but others did.

In the 1960s sun-seeking tourists from Britain and Germany went to southern Portugal and their money helped fund the bloody colonial wars.

Candidates for the few elected offices who criticised the regime were hounded, and after they lost the election, they were punished. Opponents could not win because the ballot boxes were stuffed. There was nothing subtle about this procedure which the international media reported. Salazar had no personal involvement and in many cases may not have known it happened, and he even occasionally inquired but was always readily satisfied by a bland response from an authority down the line.

Salazar insisted on fighting the three African wars within a balanced budget which had become an article of faith with him. The result was a constantly ill-trained and under-equipped army in the field. There was virtually no medical service in the army, and the quiet brain drain that had been going on for a long time increased in pace. Disease maimed, injured, and killed far more Portuguese conscripts than bullets.

Portuguese conscripts in Africa.

Portuguese conscripts in Africa.

Politics made strange bedfellows. Portugal allied itself with Rhodesia and South Africa with Israel supplying many of the arms. Portugal desperately holding onto its empire allied itself with a break-away colony Rhodesia. Portugal that claimed no colour bar in its Lusotropical colonies allied itself with the apartheid South Africa. Portugal which was the origin of the Inquisition’s attack on Jewry relied on Israel.

Later there were all those Cubans. Cubans? Yes, Fidel Castro turned the Cuban army into mercenaries, 25,000 of them, and sent them off to Africa. The Soviets paid Cuba in oil extracted from Romania. Blood for oil.

Likewise Salazar’s determination, in a convoluted manner justified by Lusotropicalism, to swim against the tide of post-war decolonisation led to three wars in Africa, which Portugal could neither sustain nor terminate. It held grimly onto Macau and Timor while doing nothing to improve life in either. It held onto even more grimly Goa and the associated enclaves grandly called the Portuguese States of the Indes when India was born. In a round-about order, Salazar told the Portuguese governor of Goa to fight the Indian army to the last man, but this governor decided he did not receive this order and ignored it. When he returned to Portugal, there was an inquiry into Who Lost Goa, but nothing came of it and the one-time governor went into retirement to write his memoirs. Another example of Salazar’s forbearance.

The material benefits from the colonies, even Angola, the richest, were small against the costs of retention. Retention was about prestige, not money, and Portugal’s distinctive raison d’étre, Lusotropicalism.

In this context he also broke with the Catholic Church because priests, bishops, and cardinals decried the murderous brutality of the wars, particularly that in Mozambique. Salazar’s response was to blame the churchmen for interfering with secular matters. He would hear no more of it, and measures were taken to intimidate some churchmen, and that engaged Papal attention. The dogs in PIDE were off the leash. Again Salazar did not authorise the use of poison in water and poison gas, but those to whom he entrusted the war did, and when it was challenged, Salazar accepted their denials without question.

Though not a workaholic, his workload grew during the years of World War II when he was in effect Prime Minister, Minister for War, Minister for Finance, Minister for Industry, and Foreign Minister. He laboured into most nights writing out his directions, thoughts, questions, orders, reports and reading everything he could get his hands on about the war and international events in a corner office visible from the street. Passers-by knew O Chefe was on the job. After the war he did share out the work more to a cabinet, but fretted when others made decisions.

He was a micromanager and seldom delegated and never easily, and certainly not anything important, accordingly the log-jams occurred, because for a decade, before, during, and after World War II, everything was important. The book succeeds in showing how both Salazar and the Estado Novo he created changed over time from benign authority in the troubled times of the 1920s to a suffocating and malign authoritarianism with the reality of violence. While violence was not the means of ascent, it became the means of continuation for Salazar and the Estado Novo.

Salazar was Portugal for more than forty years and the regime he created lasted fifty years. In his later years in the later 1960s the Portugal he knew as a young man in the 1920s remained fresh in his mind, chaotic, destitute, a laughing-stock in Europe, divided, and against that his regime was orderly and disciplined. One observer said, there is no such thing as Salazarism, there is no ideology, no program, no narrative, no policy, just Salazar at his desk every day responding to what happens with his pen. His responses became less and less flexible, and more and more blanket.

Nor was there any succession plan, in contrast say to Franco in Spain whose rule gave way to the restored Monarchy. A few times in the 1960s confidants suggested a lighter workload for Salazar, which could be arranged by making him President, but he rejected these suggestions with increasing vehemence. Finally in 1968 he became infirm and went into a coma for weeks. In the confusion, his cabinet turned to Marcelo Caetano who inherited quite a witches’ brew. Caetano had long been a private critic of much of the regime, and had at times been side-lined because of it. He held on until April 1974. He did try to make changes but the the Old Guard was so well entrenched and so frightened of change, he could do little until the roof fell-in.

A word on the nomenclature. Portugal had a president of the state and a president of council of ministers. Two presidents. The state president was elected for seven year term, and through Salazar regime the electorate decreased as it was ever more tightly controlled to ensure that the right candidates prevailed. The state president designated the president of the council who then formed a government. The state president performed the ceremonial tasks, received the credentials of foreign diplomats, cut the ribbon on national days, shook hands with returning soldiers, escorted state visitors here and there. The president of council made the decisions.

The reality was that Salazar fixed the selection and election of a state president who would comply with him. The electorate was reduced step-by-step to those who held official positions, all of whom were appointed by the Estado Novo, i.e., Salazar.

Salazar was president of council who could have been dismissed at any time by the state president, and in effect he was when he went into a coma.

Most international media overcame these repetitive, odd, and confusing terminology by referring to Salazar as prime minister to the state president.

Salazar did regain consciousness and lived another year. No one had the courage to tell him he was no longer in charge. But there was no pretence that he still ruled.

Despite all his efforts he did not leave Portugal a better place. It remained primarily agricultural and its agriculture depend on animals and strong backs. Roads were primitive outside the cities. Telecommunications scare and unreliable. Education was abysmal, as was health care.

On European tables of comparison, Portugal was the Louisiana or Europe, last on the good things, e.g., longevity, health, and first on the bad, infant mortality, illiteracy. Even less had been done in the countries of the empire, which he held so dear, to improve the lives of the Lusotropicals. Salazar would never admit any of this, but it was apparent to some around him, like Caetano, and to the world media and diplomatic corps.

Though he never married there were a few women in his life; yet he nearly had no private life, nor any interests outside work. At the mass in Lisbon at his death, the government officials, members of the media local and international, and diplomats far outnumbered friends and family. In this latter group were his two surviving sisters, his loyal housekeeper, and two nieces.

In the last chapter the author suggests that Salazar had three abiding motivations. The first was that he was agent of providence who had to shepherd Portugal. In his earlier career this conviction had a religious dimension but this receded with time. Second was the belief that without him the delicate arrangements would collapse. Third that the empire was Portugal and it had to be held. He was certainly right about the second above. Without him the Estado Novo was hollow.

Personally he was frugal and his family — the four sisters — benefitted in no material way from his rule. When Caetano took over, Salazar was out of job, out of the official residence, and destitute. He had only the clothes on his back. The government had to make special provision to pay for his hospitalisation and subsequent care and residence. He was without an escudo to his name.

In a television program in 2007 seeking the Os Grandes Portugueses of all time, Salazar prevailed over Ferdinand Magellan, explorer; Vasco de Gama, sailor and innovator; Luis vaz de Camöes, poet credited with creating the Portuguese language; Henry the Navigator, unifying political leader; Antonio Egas Moniz, Nobel Prize winner in medicine; and José Saramogo, Nobel Prize winner in literature. If ‘greatest’ means doing what no one else did or is ever likely to do, then Salazar is the choice.

The introduction of the book, while well written and informative, bemoans the difficulties of the scholar in a self-indulgent way. What is said is true, ‘Amen to that, Brother,’ but the introduction is not the place for it. It aroused in my mind the difficulties of those scholars who do not have jobs at all, of those scholars who cannot follow their interests, those lacking connections and direction cannot get good work published, and all those other people whose lives are far harder than competing for research grants or waiting for a sabbatical.

*****

A Portuguese once told me about Portuguese world literature as we sat, bored stiff, at a conference presentation, no doubt one involving post-modernism. Yes, the entire world’s literature was available in Salazar’s Portugal. But it was cut down to Portuguese-size. ‘Huh,’ I said, always quick on the uptake.

Perhaps reading Shakespeare was like reading this newspaper.

Perhaps reading Shakespeare was like reading this newspaper.

Censorship abridged, edited, and changed Shakespeare, Milton, Moliêre, Darwin, Rousseau, Göthe, Eliot to remove the big and the dangerous ideas of personal autonomy, political rights, regicide, consent of the government, self-expression, women’s capacities, dissent, immorality, growth through trial and error, divorce, protestantism, and so on. While Plato’s philosopher-kings remained in the Portuguese edition of ‘The Republic’ the community of wives, children, and property — communism — was excised, along with Plato’s repeated assertion that women must contribute to the society as do men. Also snipped out was the homosexuality, the marriage festivals, and the noble lie. I had asked about Portuguese translations of ‘The Republic’ and that question led to the conversation adumbrated above.

I have had an itch about Portugal ever since the Carnation Revolution of April 1974 which captured my attention in the early months of my first year in Australia, however that event was obliterated from the local media by the murder of five Australian journalists in East Timor after the Portuguese left and the Indonesians attempted to annex the area. These murders are re-visited every ten years of so by the Australian media. While what happened and who did remain unknown speculation recurs and recurs with attendant breast beating.

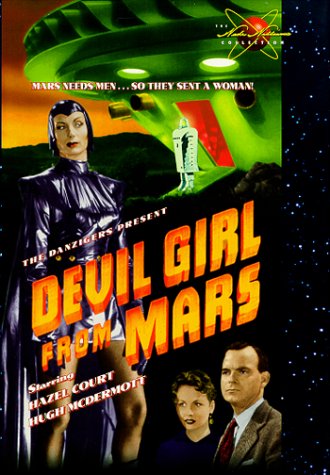

‘The Devil Girl from Mars’ (1954)

Inspired by ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951) the prodigious Danziger Brothers — Harry and Edward — turned their hands and low budget to sci-fi in this effort. It offers inspired casting and a prescient screenplay, and we watched it the other night. Well I watched it twice. to get the subtlety.

Devil Girl, indeed. Patricia Laffan is THE movie. When she is on screen there is tension, there is presence, there is drama and when she is not, there is none of the above. On her more below.

In the remote Scots moors an odd assembly takes refuge in a lonely inn. A married couple run the place, baby sitting a grandson, with a handy man, elderly Jim, and girl of all work who is mainly seen at the bar. With the winter approaching the only guest is a beauty from the big smoke and then a scientist with a newsman in tow arrive to investigate the strange lights in the sky. An escaped convict also insinuates himself in the group. Otranto Inn is now ready for the night ahead.

The scientist and newsman provide masculine leadership by debunking the worries of the women about those strange lights in the sky. ‘Just your imagination, my dear.’ They seem to have forgotten that those lights are why they are there in the first place. By now we know better. After the predicable confrontation with the convict, instant jealously over the beauty, and more condescension, Nyah appears!

Can that woman make an entrance. Seven times by my count. Shazam, indeed. The part of Nyah was made for Patricia Laffan, who is cool, calm, implacable, and pronounces her diabolical purpose with diction that would bring a smile to the twisted lips of Professor Henry Higgins. Her vowels are so round; her consonants are so icy.

With a black leather body suit, a cat-like skull cap, a Darth Vadar cape, a mini-skirt avant le mot, and a ray gun, she has it all. Then there is the spaceship and within, Chani, the tin-man. (I thought she was calling him ‘Johnny’ which seemed awfully informal for Nyah, but on a long flight, well….)

Nyah has no time for small talk, nor, I suppose, for a shipboard romance with Chani; she is all business and the business is men!

The near-sighted, shuffling Jim with the feeble manner of an emeritus professor is a poor physical specimen, she declares. Poof! That’s it for Jim. He is no longer a drain on the taxpayer.

On Mars the emancipation of the women led to open warfare between the sexes. The females won, usurping the political power of the men. This eventually led to the sexual impotence of the planet’s entire male population. (Remember Louis Malle’s ‘Lune Noire?’ Look it up, Mortimer.)

She is Hillary Clinton! Come to emasculate the Republicans! ‘Go, girl’ we shouted from the couch! Grab ‘em by you-know-whats!

Just like the Republicans, the first reaction of the men is amused disbelief. What, after all, would a woman know!

After a few object lessons, the next reaction is brute force. Why negotiate when a good whack should fix things. Think of the 7MATE demographic. Efforts to beat sense into her backfire.

Stage direction. The telephone lines are down. The only automobile won’t start. Darkness falls. They are isolated and alone. They will have to work together to overcome this one woman who threatens life as men know it. Gasp!

But wait, what is the problem?

She wants men. Call for volunteers, Nyah! But stand back to avoid the rush!

The screenplay wobbles. At times she wants spirited and unwilling men and at other times the docile tweenager seems to be preferred. This Devil Girl has trouble making up her mind. How like a woman in the stereotype of the era.

The screenplay is inane and most of the acting, especially the male leads, ranges from wordy to wooden and back. The special effects are far from special, even by the standards of 1954. The tin-man clearly had no tin or much of anything else barely making it down the ramp much like the late Jim.

Lobby posters on the interweb give three women top billing. How rare is that! How rare was that in 1954.

Patricia Laffin, per the biography on the IMDB, was ‘a statuesque and striking actress with vaguely reptilian aspects, at once sinister and alluring; a smile that was as much a sneer and a commanding, imperious presence suggesting innate superiority with a delivery that was at once sardonic and disdainful.’

Stop there. That is Nyah.

Nyah is precise, frigid, fiery, and languid. This woman could be hot and cold simultaneously.

Laffan did not fit the pigeon holes of the time and was relegated to supporting roles as a villain or an eccentric. Our loss. (But she stole the show from Peter Ustinov in ‘Quo Vadis’ (1951) before hitting warp speed as Nyah.)

The men had their turn in ‘Mars Needs Women’ (1967), but Tommy Kirk in a wet suit one size to large for him just does not have what Nyah had! He did call for volunteers and not even Annette came. Mickey Mouse, indeed.

Both can be found on You Tube.

Is a picture worth one thousand words?

The cliché is that a picture is worth a thousand words. Not so.

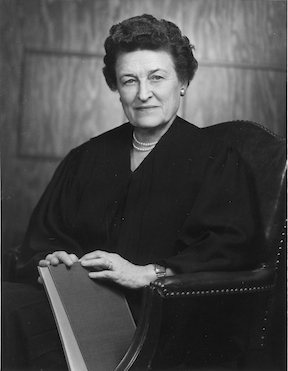

Here is a picture that has been often seen. For those born yesterday, it is Vice-President Lyndon Johnson taking the oath of office for president in November 1963.

Class. write down everything you know about the scene.

Did you know this?

At President Kennedy’s death in Highland Park Hospital, Johnson had been told by the Attorney-General’s office to take the oath of office immediately. This counsel was affirmed vigorously by the military advisors who travelled with the deceased president. Why? Why no respectful period of mourning?

In that uncertain time in the Cold War nuclear age, the fear was that a hot head somewhere might take precipitous and irreversible action. Remember ‘Dr Strangelove!’ One prophylactic was an immediate and seamless transfer of power to new hands.

It was also stressed by all concerned that the new president should get to Washington D.C. as soon as possible to take up the reins and calm public fears.

The Secret Service also wanted to insure the security and safety of the new president, in case there was more to come. The times they were indeed uncertain and foreboding.

Ergo the ragtag group around the Vice-President set off for Air Force One to fly to Andrews Airforce Base. A ragtag assembly, yes, it was; but all the same some thought did into its composition even in those dark and dreadful hours.

Before leaving the hospital Johnson, with the presence of mind he often had, asked for a judge to join the group on Air Force One to administer the oath of office. He also insured press photographers were on board to document and broadcast the moment.

And not just any judge.

He asked for a judge by name: Sarah T. Hughes. She is the woman with her back to the camera.

Judge Hughes

Judge Hughes

Johnson had nominated her twice for more senior federal judicial appointments, and each time it was blocked, because she was woman, because she was too old, because Johnson had nominated her was enough for Attorney-General Robert Kennedy to oppose her promotion.

In a kind of overdue compensation, Johnson bestowed upon her the historic role of swearing in the president there on Air Force One. But wait, there is more.

It also showed that same Attorney-General who was now in charge.

For the same purpose — demonstrating the smooth and immediate transfer of power — to calm the US populace and show the Soviets that it was business as usual, he asked Mrs. Kennedy to stand with him in the bloodstained clothes she wore. The torch was passed.

The picture alone tells us none of this. So much for the lie that a picture is worth a thousand words. This one alone is not even worth the four hundred words it takes to explain it.

When I upset a bookshelf groping for a power point a volume of Robert Caro’s magisterial biography of LBJ fell to the floor and in restoring it to the shelf, I noticed this picture.

‘A Small Death in Lisbon’ (2002) by Robert Wilson

I break my rule and write about a book I disliked, doing so in part to crystallise what it is that I did not like about, and why I tried so hard to read it.

I tried to read this book years ago, and was recently moved to try again since my interest in Portugal was kindled again a few months ago by reading about the Carnation Revolution of 1974 but my efforts to find Portuguese novels that I might like have failed.

Yes, I have read some by that Nobel Prize winner, José Saramago, but found them desiccated, didactic, and dull. In short, lifeless. They told me nothing about Portugal or any Portuguese.

Reviews of lists of Portuguese novels on websites did not help either where even the krimis were described by the deadly term ‘surreal’ that is code for incomprehensible and self-indulgent which some mistake for creativity. On such lists I found ‘Ballad of Dog’s Beach’ by José Cardoso Pires which I read and reviewed elsewhere on this blog. It did not inspire me to choose another title from such lists. As an indicator of nonsense the term ‘surreal’ is as reliable as the label ‘post-modern.’

Robert Wilson is routinely accorded the accolade of a best selling author on the covers of his many novels from major publishers. All hail. The reviews in credible sources are respectful, if not enthusiastic. Knowing that I know nothing, I tried again.

It has a split story line, then and now with some in-between, and the reader, I guess, is supposed to be puzzled about how they come together. Me, I just assumed some hocus-pocus would bring them together. I cannot abide this approach to story-telling because it puts responsibility on the reader to make sense of what is written. This joke is not for this folk.

The respectful reviewers say it offers a travelogue of Lisbon and that is what enticed me to read the book both times. So on I went, screen-by-screen on the Kindle. My dentist does not approve, all that gnashing, grittimg, and grinding of my teeth which will undo his good work. With the iron discipline for which I am famed, I quit — again — at 61%, according to the Kindle.

Here is what I found as I made my way to that 61%.

We have Klaus Felsen a German businessman forced to go to Portugal in 1941 to buy rare industrial metals for the Nazi regime and to try to prevent the British from getting them, too. It seems he is the only man for the job since he speaks Portuguese, learned from a few weeks with a Brazilian woman. Ah huh. Fluent no doubt. It is February 1941, and there is one reference to the Eastern Front, though there was not one until 22 June 1941. The hindsight is all to evident throughout.

Sometime in the 1990s we have world weary inspector Zé Coelho, who mouths gratuitous criticisms of the society he serves, and despises those who cooperated with the late and unlamented Salazar regime, a group that would have included most of the country. He wears his alienation on his sleeve. Everyone he meets is awful. Especially those with money. So it goes. When figures in police procedurals engage in this kind of cheap cynicism, my supposition is that the reader is to take it as social criticism. Ever the rebel, I take is as cheap cynicism.

There is a lot of coming and going in Lisbon of the 1990s, and I liked that. I used a Google map to follow some of it on the iPad. That kept me going as long as I did.

The book also features much sex. Both of the protagonists, Felsen and Coelho, are irresistible to every woman they pass. There is enough detail to satisfy a gynaecologist.

Felsen, the good German, also goes in for murder and torture, and these deeds are also lovingly described from anatomy textbooks: wires to the genitals of the helpless victim. No electricity, just wires. The thugs, these he kills with rocks.

Time passes in the back story from 1941 and Felsen remained in Portugal when the war ended. He gets even with all his enemies, in part, because of the love of Eva. Who? [Sound of violins over the screams of his victims,]

The Portuguese peasants Felsen enslaves to his smuggling operation are described in bestial terms that must give some armchair readers a frisson. Me, I thought how simple-minded such characterisation is. For a dose of reality read the nature poems of John Clare (1793–1864) a day-labouring peasant just like those in this story. If people do not live in cities and read books, they cannot be as fully human as … the author, the reader, the editor. Thugs live and work on Bond Street, too, and even in some universities, I am told.

The preoccupations with sex and money can be readily interpreted in two ways. The first is ‘give them what they want.’ If it sells, write it. Here we may see the hand of the publisher pushing the author along. The other is the projection of the author’s own fantasies onto his characters. Pick one.

There are no compensations in the prose. Much of it is workmanlike and gets us from A to A1. However, there is far too much that is overwritten. ‘Overwritten?’ one might ask. ‘What does that mean?’ Here are a few examples;

‘her knees looked tired’

‘an in articulate shriek’ from a closing door

‘an enclosed man’ who was waiting in the alley

his ‘breath was cigar streaked’

she rose on ‘strong legs’

the ‘walls drank in the evening light’

the school girls began an ‘elephantine dancing’

There are many, many more examples of this overwrought and meaningless prose. I just stopped highlighting them on the Kindle. Each time, this slow wit, had to read the sentence twice in the forlorn hope that there was a point to the prolix prose. Nope.

When I gave up I did take a look at the comments on GoodReads and was once again confirmed in the conclusion that it is pointless using that as a reference. The narcissism (look it up. Mortimer) of many comments allows me quickly to skip most entries, and the others read like support of relatives.

Nota Bene. We watched two episodes of the ‘Falcone’ krimi television series derived from another series by this same Robert Wilson set in Seville and found them gratuitously anatomical in the violence for no other reason than to get a restricted rating to make naive viewers think they were getting something hot. While we liked the travelogue of Seville, it was not enough to put up with the plucked eyeballs and roasted human flesh. The effort to shock is so adolescent.

I hesitated a long term before publishing this, but decided to get it out the door. Reading the imbecilic reviews on GoodReads stimulated me to add my two cents.

****

What I would like would be a krimi set in 1974 as the Carnation Revolution unfolded and in the heady-ing and confusing days that followed, catapulting Field Marshall Antonio de Spinola to the head of a committee of national salvation and driving the eternal Salazar regime into exile.

Perhaps such a book exists but I have not yet located it. The dictatorship in the person of President Marcello Caetano refused to abdicate to the upstart captains who led the uprising, and insisted on entrusting the government to a high ranking officer who, of course, had also to be acceptable to the upstarts. There was only one candidate, Spinola, whose public and private criticisms of the regime were known even if uttered sotto voce and published abroad. He did not want the job, the captains did not choose him, and Caetano did not want to concede, but the hour called the man.

Enter Spinola, pulled from one side and pushed from another. The captains wanted a quick result before their tissue thin conspiracy unravelled so they accepted Spinola as the only senior figure they could tolerate. He took on the thankless task as a last service to the country. No biography of him is available in English, or I would turn to that.

If a prospective writer wants the job, here are a few tips.

Make it linear. Have a protagonist who is not the centre of attention but a prism of others.

Also please emphasise Lisbon as a character in the story, not just a backdrop, its hills, it redolent history, the balcony flowers, the worn steps, its narrow streets, the ubiquitous churches, the funicular, the prayer apses on the twisted streets, the allure of the Azores, the stifling shroud of an ancient Catholicism, and the repression that hung over everything, the secret police, mysterious disappearances, political prisoners, the nearby Spanish border and the sclerosis-ridden dictator still crouched behind it, and the exiles in Brazil broadcasting back to Portugal.

Remember also that there were Portuguese military officers, serving and retired, in 1974 who had been volunteers in the Spanish Blue Division with the Nazis at Leningrad, including Spinola himself. Most of all, remember the three colonial wars Portugal was engaged in at the time in which Spinola alone had secured victories and made peace. Add the pirate attack by Portuguese exiles on the cruise liner the Santa Maria a few years earlier. In the larger environment there is the Cold War and the developing European Union. Rich pickings.

In the foreground perhaps the tension might spring from bringing together an odd couple, say an enemy of the regime with a defender, and each discovers something of value in the other. The stiff devout old guard police investigator who had done military service in Africa teamed with a youthful critic, maybe a journalist. The journalist discovers the police officer is serious and just what he seems to be, simple and honest, not a perverted pederast hypocrite. The officer discovers the journalist is a patriot who wants to elevate Portugal not a slavering communist set on destroying the country and raping nuns.

There are plenty of incidents to choose from, even before the radio music signalling the rebellion, and then later the military counter-coup, the subsequent communist effort to seize power as Lenin did in October 1917, the democratic descent into confusion. All this was in the cities, while in the countryside life continued to follow the rhythm of nature. Or did it? Maybe not on the Spanish border. Maybe not on secluded coastlines where small boats might land unobserved, perhaps from Brazil.

Add to this the reaction of Big Brother in Spain. Franco was still a factor, catatonic though he was.

I have watched some of ‘Capitães de Abril’ (2000) on You Tube without the benefit of English subtitles. Earnest, this I could see, but lacking in tension to this distant viewer.

Evariste Clovis Désiré Pel, biography

It is time that Chief Inspector Evariste Clovis Désiré Pel had a Wikipedia biography along with Jules Maigret, John Steed, James Bond, Lois Lane, and Xena.

He appeared full grown like Athena in 1979 (‘Death Set to Music’), Pel has had a long career in crime, crime-fighting, that is. the last outing was in 2002. His biographers have been John Harris, writing as Mark Hebden, succeeded by Juliet Hebden. Pel was a child during the German occupation, ten or less.

We shall start with that name. It is a cross to bear for Monsieur L’inspecteur Pel, who cringes whenever he is asked for his full name, say when renewing the driver’s license. In reply he hunches and mumbles to limit the number who hear. Three forenames is too many and none of them is particularly masculine, but the worst part is the third, Desired One — Désiré — a name usually reserved for girls.

His second most important characteristic is that he is in, for, and of Burgundy, and if possible never leaves it. Ever. Beyond Burgundy is, well, France (with the cesspit that is Paris) which is a foreign country to Pel, and beyond France lies darkness. In his moments of calm, few as they are, Pel savours Burgundy as Eden on earth. The trees, the patchwork fields, the stone farms houses, the blue tiles on roofs in the capital, the Palais de Ducs, the mellow yellow sun, the cuisine, the wine, all is perfection. He positively sings its praises, in his mind.

He is to the core a flic, and nothing but. ‘You’re nicked, you slag,’ snarled by Inspector Jack Regan would warm Pel’s heart. He would not understand the idiom but he would grasp the music of it immediately. Pel has risen through the ranks from the uniform service, where he stood in police lines while students from rich families threw rocks at him personally; and these students are now lawyers and doctors who fiddle their income tax, he is sure. Here is another Pel characteristic. He takes everything personally. From thence to Detective Sergeant, Inspector, and Chief Inspector. In the later role he has ten detectives to direct.

We meet Pel in his forties, he is short, slight, nearly bald with a few wisps of mousey hair, near-sighted with reading glasses pushed up on this head. Whatever clothing he dons at home, by time he arrives at the nick he looks like a hobo just off the rails. Even his best blue suit, the one he bought against the day, which day has not yet to come, when he receives a Légion d’Honneur from the President of France, becomes stained, creased, begrimed, and baggy as soon he takes it out of the dry cleaner’s paper. By the time he gets to the office, it looks like a sleeping bag gone wrong.

He is completely and totally addicted to Gauloise cigarettes, of which he smokes at least a pack of twenty a day, living in constant dread of running out, while promising that each one will be the last. Blind panic the strikes him when the prospect of running out arises.

Pel is an Olympic worrier. He mostly worries about his health. Those cigarettes! If he passes a person in the street who coughs, Pel is instantly paralysed with the fear that he is about to catch a mysterious mortal disease. Dr. Minit has long grown tired of his panics and laughs at him while offering a drink, thus confirming to Pel’s mind that he has little time left since the quacks never say if it is bad news.

If he is out of the office for long, he worries that the Police Judiciare will collapse without him, and so he is a frequent nocturnal visitor to the office. He is a lousy driver because he is always thinking about his cases or his health.

Despite squirrelling away in the bank nearly every franc that has come into his possession, he fears a life of penury, the more so when he retires on a police pension. This worry is despite the bank manager’s comment that Pel has a fortune in his account. He also fears he will be forced to retire all too soon since he is neither liked nor respected, and he does not understand the computer system that is coming online.

By some dark Faustian bargain, he has a live-in house keeper, one Madame Routy who exercises a domestic tyranny. In all of Burgundy she is the only person who cannot cook. She serves up sludge, called stew every night, which more often than not it is his only meal of the day. Worse, she watches television all day and all night with the volume at thunderous plus. Will his shabby house vibrate itself into destruction? He abides because he dares not rebuke her. She might quit and where else could he find a house keeper to live in his dilapidated house and work for the meagre pay he can offer. Moreover, her nephew Didier comes to visit sometimes and Pel likes Didier. When the boy grows up and enters the police service, Pel swells with pride before breaking into a sweat at the thought of all the dangers that will afflict Didier as a constable.

At the PJ he runs a tight ship. Few words of praise escape his lips. Requests for time off are met with ‘Non.’ He is bitterly jealous of his senior sergeant Darcy’s easy way with women, and positively livid that Darcy always appears to have just stepped out of fashion magazine, even when Darcy has been up all night on surveillance. So livid is Pel that to make himself feel better he searches for some fault to criticise in Darcy. He is even more angry because nothing he says phases Darcy who shrugs it off.

Pel loathes Sergeant Misset who combines being lazy with being stupid to a high order, but Pel can find no way to shed him from the squad where he spoils everything he touches. Pel bears a lifelong grudge against the traffic division which arranged for Misset to be transferred to his squad.

Then there is young Nosjean, the impoverished Baron de Troq, Lagé, the soon to retire Krauss, Claudie Darel whom he is sure will take his job away from him because she is terrifyingly smart, and then there is the Lion of Belfort who leaps into action at light speed: Annie Saxe, who is called La Lionne de Belfort for her mane of red hair and her origins in Belfort where there is gigantic statue in red sandstone of …. [Go on, guess.] Yes, a lion!)

Pel is a very effective officer, calm, decisive, and confident. In a crisis he knows what to do and how to do it. He rattles off brisk orders that give each officer a task and knits them together into a concerted action. While bemoaning his ill health, he works younger men and women into the ground.

Often he prefers to watch and wait, withstanding bureaucratic, political, and media pressure to act. His steely resolve in such circumstances inspires the members of his team, while he assumes they despise him.

He speaks a passable English. His father insisted that the children, Pel and his two older sisters, learn English on the assumption they would go into the wine business. Though he overflows with all the prejudiced stereotypes about the Les Rosbifs, he sits in a ‘comfort anglais,’ drinks scotch, and savours Yorkshire pudding on occasion. His one effort to prepare Yorkshire pudding bore a passing a resemblance to the Battle of Somme, such destruction did it leave in the kitchen for Madame Routy’s return!

His solitary life is lightened by the interest of the widow Madame Geneviève Faivre-Perret who seems to enjoy his company. Darcy was instrumental in their liaison and occasionally has been known to observe their affair with an bemused smile. While Pel is desperate for Madame, he is also terrified that he cannot afford to marry, to go out to dinner at a good restaurant, to buy a new car, to move house, and he cannot possibly change, much as he would like to do so. He worries himself sick about telling her his whole name!

He tries many things to please her, most of which backfire. He is as tongue-tied and confused as a teenage boy where she is concerned. All of this seems to amuse her still more. His daily resolve to quit smoking takes on an added urgency because he is sure she disapproves, and the fact that she has never said so, that being the final proof! His efforts to quit smoking are many and useless.

Pel has no interest beyond policing and so Darcy speculates on what Pel could find to talk about with Madame Faivre-Perret. By the way, Darcy lets Pel’s frequent bouts of bad temper slide off without reaction, which often infuriates Pel all the more. Pel is indeed irascible.

Pel sometimes dreams of being a Maigret, stolid, implacable, all-knowing, infinitely patient, imperturbable with a Madame Maigret to give him coffee on 3 a.m. call-outs and fill him with delectable home cooking. Ah… He entertains this fiction most often when swaddled in all the wool clothing he has, looking like the Michelin man, standing a midnight watch on a windswept hilltop in a January winter where the temperature is sub-zero and the gale is Siberian, or perhaps Arctic. Worse, the wind makes it impossible to smoke! Another of Darcy’s annoying characteristics is that he does seem to mind the weather — hot or cold, wet or dry — as he waits it out next to Pel.

It’s the economy! Again! And again. And again.

Every day for the last fifty years the Australian economy has been on the verge of collapse.

Not a week goes by but that the financial media offers dire warnings about increasing house prices, falling house prices, the high value of the Australian dollar, the low value of the Australian dollar, disastrous pay raises, long overdue play raises, the flight of capital, the threat of incoming capital, the burgeoning public deficit, credit card victims, exploited workers, impossibly high interest rates, perilously low interest rates, and on and on and on and on.

The slightest change in the cost of shoes or rent of 0.001% is described as a ‘massive leap.’ Any increase is crippling and any decrease is devastating.

Ad nauseam, indeed.

‘Wolf!’ has been cried so loudly and so often and in such contradictory terms that I have developed lupinophobia. Figure it out, Mortimer.

While all this nay saying occurs, the GDP, the GNP, calories eaten, the Per Capita Income, life expectancy, population growth, household consumption, superannuation savings, they have all increased to historically high levels and far above that of 95% of the world’s population. Most people in the Lucky Country are lucky enough to live like kings and queens compared to most of the rest of the world. compared to a their grandparents, compared to the entirety of history.

My conclusion is that hysteria is the only register for the journalist, who is completely detached from reality. Alternative facts have long had roots.

Rupert’s Organs set another record

How low can Rupert go? Another new record.

I have noticed in the ‘Times of London,’ the ‘Wall Street Journal,’ and our very own ‘The Australian’ and no doubt Fox News (but I never watch fiction) that President Barry ‘Bomb ‘em’ Obama is now being sledged.

In an effort to suck up to the Blond Beast, and with Hillary Clinton sidelined, Murdoch Rupert’s organs are now devoted full time to blackening Barry Obama. [Get it?] The snide racism of that woman on Fox News, who has now gone to NBC to continue the bile, is not enough. (The business decision was no doubt that she would drag her audience with her to NBC in the main stream. How the mighty NBC has fallen.)

Now that Vladimir Putin is the Blond Beast’s best friend, Obama cannot be disparaged for being soft on Russia, so….

In a creative leap, the Organs of Rupert have decided — sit down — Obama is a closet, no not that, a closet Marxist! Yes, they have! It has been drumpeted as news, in feature articles, and one of the local hacks has slurred it out a keyboard in an op-ed piece. Piece, indeed.

Proof once again that there is no limit to hypocrisy. (Mitch McConnell has a long way to go to compete with this standard. Keep trying, Mitch! [He hasn’t got a chance, but it doesn’t hurt to see the pathetic clot try.] )

Hypocrisy yes, but hardly original. The Alt Right nut cases have been saying this for eight years. Or that he is an Islamic fundamentalist. Or an alien spawn. Or…… They cannot seem to make up their minds. Wait, ‘minds,’ maybe that is the problem.

But now the nut cases are in charge. H. L. Mencken was right.

Here’s a flash.

Putin and the Blond Beast will pair up as running mates in the next elections in each country.

Or, another:

The Blond Beast will sell, er, marry off one of his children to Putin to cement the alliance.

Hillary Hating, the bile continues.

The post-mortems of the 2016 presidential election in the United States flow. It is all so simple, no wonder the PhDs could not see it coming and still cannot see it going. She is a woman. End.

[Warning, this post is all text. The graphics I reviewed to illustrate Hillary hatred were all so crude and stupid I chose not to include them. They make the programming on Chanel7MATE look refined and cultivated.]

By some mischance I stumbled onto some Hillary Clinton hating web sites the other day. I was so stunned by the cancerous bile that I could not immediately click on with my mouse finger. I have since recovered from the shock of a head-on collision with the whacko sickos. A brief digest follows.

Hillary Clinton has sold nuclear weapons to North Korea. (Evidently she carried them to Japan in her luggage when Secretary of State, and ducked into Chinese submarine in Tokyo Bay to hand over the goods.) In return North Korea paid millions of dollars to the Clinton Foundation. This is the form for many of the fantasies. As if North Korea had millions, apart from counterfeit.

Hillary Clinton has secret meetings with the Elders of Zion to collect still more dosh for the Foundation. As per the protocols of the Elders of Zion these meeting have included a banquet of roasted Christian suckling babies.

Want to know who has funded and armed ISIS? Look no further than Hillary Clinton. She did it.

Ku Klux Klan leader found dead. Guess who did it!

That tornado that destroyed Smallville, she brewed it in her witch’s cauldron.

Bill Clinton went vegetarian for no other reason than to destroy the All-American junk food business. Who put him up to it? Guess! Hillary!

It turns out she plotted with the Russkies to hack into the electoral system and puff up her vote.

The home team lost in the state finals because of referee’s call, well, she paid off the ref to favour the other team.

No villainy is to small for this one-woman coven.

I will not identify the websites since I have no wish to encourage visits.

I stumbled on these when I noticed an angry rejoinder to some innocent remark on the Facebook post about her lead in the popular vote. How, I wondered, could anyone dispute this fact. Little did I know.

It goes on and on, but I don’t.

These fantasies are so absurd, it would take forever to unwind and refute them.

Conclusions that are not reached by evidence and reason, in any case, will not be amended by evidence and reason.

That there is not one scintilla of evidence to substantiate these claims, which is readily and freely admitted in some cases, and cited as the ultimate proof of her guilt. She is so nefarious and spectral that she leaves no evidence in the mirror. (Figure it out, Mortimer.)

Hating Hillary meets some kind of emotional need in the haters. So it seems given the intensity of the SHOUTS. Yes, they are frequently in capital letters.

However it is not limited to the lunar right but can also be found on the lunar left. The King Street socialists in Newtown, the ones who tape their rants and dire warnings to the street light posts failed to predict the U.S. election result. The old crystal ball is not what it used to be.

For months these semi-literate damnations, each more outraged than the last, denounced Hillary Clinton as a soulless golem who eats proles for lunch and sups with the military-industrial complex.

Coda: The mystery to me of her defeat it how someone so smart, so organised, so well prepared, such a master of the game, did not clinch the states necessary to get the electoral votes. Maybe she listened too often to Al Gore. No wait, surely no one listens to Al Gore.