A Portuguese krimi set in the 1960s during the dictatorship of Prime Minister Antonio Salazar who ruled from 1928 to 1968 with both velvet glove and iron fist. A body washed up on a beach and the police arrive. The corpse is that of a man, slightly disfigured by the water but clearly murdered, who is identified as army Major Luis Dantas Castro, a soldier with a distinguished record in Portugal’s many African wars.

The homicide squad opens a dossier, but then it seems PIDE is involved. PIDE? Policia Internacional e de Defensa do Estado, the secret political police. Some months before Dantas had escaped from confinement for plotting the overthrow of the regime. Much of the novel is almost documentary as Inspector Elias Santana studies the dossier. Footnotes add to the verisimilitude.

The inspector is an introspective, methodical, and repressed fellow who speculates, even fantasises about might have happened. Was Dantas killed by government agents? By his own comrades in conspiracy? Or because of sexual jealousy? Elias tries to reconstruct Dantas’s last few weeks of life, working from scanty evidence. Elias uses his imagination to create the scenes at the conspirators’ hide-out that led up to the murder.

Sad to say that the novel is cryptic, hard to follow at times, and of most interest to those curious about Portugal of the time. And they were interesting times.

José Cardoso Pires

José Cardoso Pires

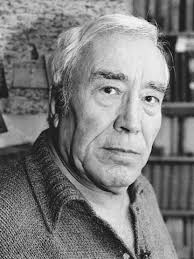

In the 1960s the Portuguese Army chaffed at the isolated and insular dictatorship, in part because it was under-equipped and under-funded for the ambitions of its officers and also in part because the regime neglected its restive colonies which the army had to secure. At the time the Portuguese Empire included Goa and two other smaller enclaves in India, East Timor, Macau, Angola, Mozambique, Sao Thomas, Cape Verde, the Azores, and Guinea Bisseau and…. The one that got away, Brazil.

Portuguese Africa

Portuguese Africa

Between 1960 and 1974 Portugal was engaged in three colonial wars in Africa in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea Bissau.

While other European powers had been, often reluctantly, withdrawing from colonial empires, Portugal, neutral during World War II, had not. By 1974 it had 220,00 soldiers in combat in Africa. The financial, social, and political impacts in Portugal were extensive. The combined populations of Sydney and Melbourne come to about eight millions, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Imagine them together sustaining three wars in northern Asia without allies.

Salazar was an intellectual, an economist by education, who conceived of Portugal as a pluri-continental, multi-cultural nation. The colonies were provinces which were at a distance from Portugal, but represented in the parliament. Salazar wrote papers and gave speeches on these themes which taken together with Portugal’s undiluted Roman Catholicism, largely untouched by the Enlightenment, made it the New Jerusalem for the entire world. He termed it the Estado Novo, or the New State, a model for all others to follow. This backward, repressed, impoverished, and inward looking country, according to Salazar, was the only pure expression of the West! (Compare to Albania for its communist purity at the same time.) Like many intellectuals, he apparently mistook words for deeds, and was content to talk, not act.

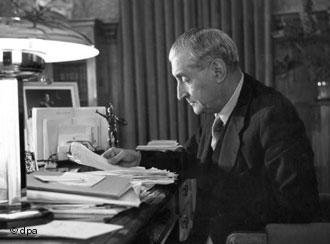

Antonio Salazar

Antonio Salazar

During the two generations that he dominated Portugal, it was sealed off from the world. Border control was stricter than in Berlin before the Wall. The PIDE had a reputation like that of the Statsi though not the same kind of massive budget.

Travel was restricted and all travellers had their baggage searched. not for drugs, but for books that might be illicit. Karl Marx was at the top of that list but also on it were Thomas Paine, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and William Shakespeare.

A special literature evolved, cut down to Portuguese size. Huh? All the great works were translated and edited to remove the big ideas of autonomy, liberty, human rights, majority rule, women who were not barefoot and pregnant, judicial review, the rule of law, equality, these were all removed. For example, Marie Curie was excised from science texts. The Beatles’ music was banned. Foreign movies were cut for screening to remove ideas as well as sex.

Even Spain, ever a frenemy, was viewed as lax and kept at arm’s length.

Brazil was a problem. The regime wanted trade and cultural relations with it because it was and remains the largest Portuguese-speaking country but though it had its own dictatorship, it accepted Portuguese exiles who set up opposition groups there. Because Portugal allowed first the Allies and then NATO to use the Azores it was tolerated and left to its own devices during the Cold War. Perhaps Salazar even hoped that one day Brazil would return to the Portuguese embrace.

There were incidents including the high-jacking of the Portuguese cruise ship the Santa Maria in 1961 by some army officers in mufti. They captured the ship with the aim of going to Angola, amid much publicity to attract supporters, to set up a government in exile. They were soon apprehended as pirates, and instead went into exile in Brazil.

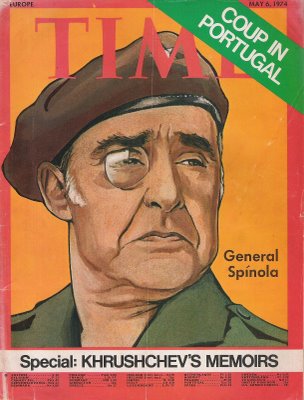

When the African colonies rebelled with some encouragement and very little support from the USSR, the overstretched Portuguese army lost. Betrayed by the regime, now presided over by Salazar’s heir Marcello Caetano, another economist, junior officers (captains, even lower in rank rather than the Greek colonels) effected a coup d’état, and into the breech stepped the flamboyant General Antonio de Spinola (1910-1996), who had had combat successes in Africa yet was known to oppose the wars. The coup was set in motion by a signal, namely a certain fado ballad in which a carnation was a token between two lovers was played on national radio at a specified time. Thus began the Carnation Revolution.

The regime, seemingly eternal the day before, fell in one stagger. The result morphed into democracy in Lisbon. Spinola wore a monocle, ergo flamboyant. There are a few parallels to De Gaulle’s return during the Algerian crisis in France, but with this difference, Spinola was committed to ending the wars and he did. It was said then and now, that only he could have done this. He had served among Portuguese volunteers in the Spanish legion with the Germans at Leningrad, and had led successful military operations in the Portuguese African colonies. His family was connected to Salazar. As a result, he had credibility and prestige with the old guard, but at the same time he was a hero to the captains and earlier he had made clear in writing his opposition to the wars at the expense of his own career.

‘The Murmuring Coast’ both the novel and the 2004 film comment on Portugal’s African war(s) in a restrained way. The film screens on SBS now and again.

True his word, General Spinola ended the colonial wars from one day to the next and negotiated settlements with the African colonies, made contact with China about the future of Macau, and left Timor. Thereafter as Portuguese democratic politics went left in the heady days, now largely forgotten, of Euro-Communism, Spinola went into exile himself to Brazil, where he plotted against the democratic regime with a small group of acolytes in a pathetic coda for a larger than life figure. He did return to Portugal and lived the rest of his days in quiet retirement.

There seems to be no biography of him in English.

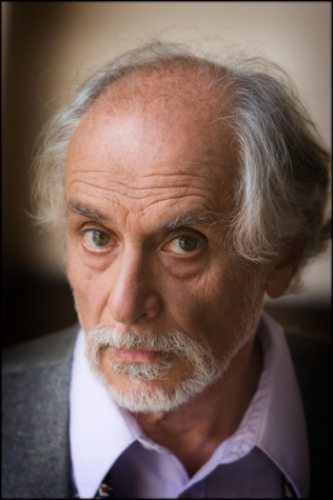

‘Alexander Hamilton: A Life’ (2003) by Willard Randall

Alexander Hamilton (1755 –1804) was widely expected to succeed George Washington as leader of the Federalist party, which advocated a strong central government. That is until he was murdered by Vice-President Aaron Burr. Yet his face is there on the ten dollar bill. To find out why, read on.

Born out of wedlock on the Danish island of St Croix in the West Indies, he was legally a bastard. His mother, a French Huguenot, died when he was fifteen and left him an orphan. He attended a rabbinical school on the island because the Christian schools would not accept a bastard. He was both intelligent and quick to catch on, but his education was basic. He went to work at fourteen for the Cruger Brothers trading company in St Croix which had headquarters in New York City. In later life he was religious, but it is not at all clear he was ever baptised.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

When the local proprietor, Cruger, became ill and returned to New York for treatment, he left his chief clerk, the boy Hamilton, in charge for a few weeks that unexpectedly turned into months. Hamilton had lied about his age to get work by adding two or three years. As Cruger’s absence stretched over the months, Hamilton ran the business, made decisions, signed orders, negotiated prices, initiated law suits to secure payment, signed correspondence, deposited monies, honoured contracts, and took several initiatives. When the owner returned he was very pleased with Hamilton’s stewardship.

This period of management was crucial to Hamilton’s subsequent career. St Croix was part of the triangle trade in slaves, rum (sugar), and New England goods. The man-child Hamilton ran slave auctions. He bought from and sold to New England merchants, who came to know his name from these transactions.

He also drew some conclusions, albeit slowly. First that slavery was abhorrent after his first-hand experiences, and he acted on that conviction often in later life. Moreover, he concluded that those American colonies with which he was trying to do business needed a cash currency of their own, and to get that they had to be united. He also acted on this point later. Without that the business was transacted by converting Spanish dollars, to Portuguese Josephes, to British pounds, to weights of gold or silver, and so on. None of these European currencies was readily available in the New World. Hence transactions were often paid with a mix of coins, metals, and bartered goods. Moreover, a mix of currencies and coins that worked for a Massachusetts contract, did not work for a New York one, and so on and on.

A hurricane flattened St Croix, bringing business to a standstill and in the doldrums Cruger decided to send his protégé Hamilton to the United States for an education. Smart as he was, Hamilton had no systematic education and had to start from scratch to prepare for the entrance examination to the College of New Jersey, before it became the country club of Princeton, until Woodrow Wilson made it into a university. His employer’s connections put him in the company of the social and economic elite just as New York City was becoming the chief city of the American colonies.

Arriving by ship in Boston, he found it an armed camp. The ten thousand citizens were sequestered by two thousand British army regulars. There had much restiveness among the locals because the British parliament was intervening ever more directly into each colony in the search for taxes to pay debts incurred in London. The crown dissolved reluctant local assemblies. Direct taxation was introduced. Protests were ignored. Delegations to the governor(s) were met with a wall of red coats. As Edmund Burke said, the British government’s actions drove the American colonists to rebel. All of this was much discussed by his travelling companions in the week-long stage coach ride to New York City.

Some of the division was religious with Anglicans siding with the crown, and Presbyterians with the colonists. To some Anglicans to dispute the prerogatives of the crown was blasphemous as well as treasonous.

Hamilton had a box seat to observe events because the members of the New York City elite he joined were in the firing line. It was their businesses being taxed, regulated, controlled in ways never before done.

While Hamilton performed well in the Princeton entrance oral examination, he was refused a place. No explanation survives. The author speculates that his bastard origins might have become known. When Hamilton next visited at Princeton, he came with cannons (during the Revolutionary War). He then turned to King’s College in New York, which was dominated by Anglican loyalists but…needs must. In a later evolution it became Columbia University to leave behind the English connection.

The pot continued to boil and the precocious Hamilton wrote anonymous pieces for newspapers on Enlightenment rights, though largely unschooled, he had read some of John Locke and had a good turn of phrase using natural and geographic images that communicated readily. But by day he sat dutifully in class and kept his opinions to himself. He did however join one of the militia companies created by the Sons of Liberty, which drilled around the local Liberty Pole. He was good at mathematics and learned trigonometry that made him an artillery officer in no time. Later he wrote the bulk of ‘The Federalist Papers’ which was once required reading in every college American history course.

He was not particularly good-looking nor did he speak well, or have a commanding presence according to contemporary descriptions and reports. A sloping forehead, a lantern jaw, a disproportion among his features, close-set eyes were described by his friends. Some of these were later masked by artistic technique in portraits.

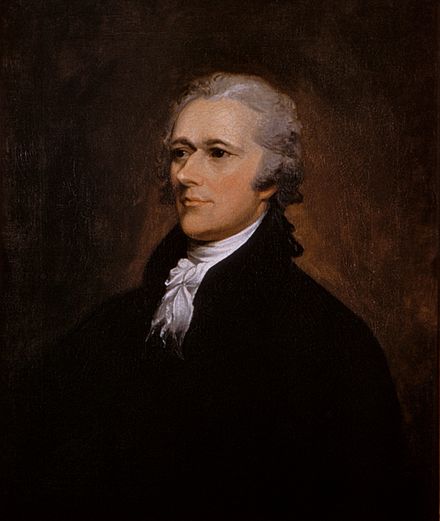

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

But he did have brains and a will to match which took the form of an enormous appetite for work.

First and foremost, he was Washington’s chief of staff during the last half of the Revolutionary War, and Hamilton did much to win it. He founded the Artillery Corps, and made the first plan of acquisition and use of cannons. He wrote the Infantry Drill Regulations, the training manual of the US Army, and he trained much of George Washington’s Continental Army with it in hand. He was twenty-three at the time. As a field commander he promoted men from the ranks to officers, and this outraged many of his social superiors, but he persisted, and prevailed. He outraged still others by advocating, proposing, and planning to emancipate slaves to help repel the British in the south. On this one he did not prevail but antagonised many. Washington supported both these latter initiatives, but even his prestige was inadequate to the second proposal.

One of the many ironies is that South Carolina refused to consider freeing and arming slaves, and Charleston was then duly invested by the British who promptly freed its slaves and enlisted them in the British navy, about 2000 in all. By the way, Dr. Copeland, the indomitable black physician in Carson McCullers’s ‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’ (1940) named one of his children after Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was slandered by the Tea Party of the day for his bastard birth, his lack of parents, his Jewish education, and his foreign birth. An orphan, a bastard, a semi-jew, and foreigner. Imagine what Trump Donald would make of that. ‘What a loser!’ For several years while attached to General George Washington’s staff, Hamilton was responsible for all prisoners of war. He negotiated with the British many times to exchange prisoners, to improve living conditions for Americans imprisoned, to seek compassionate release for individuals, to create a schedule of exchanges, to procure medical treatment and food for both American held by the British and for British held by Americans. For his trouble, rivals labeled him a British spy. With the same scruple, when the French entered the war as an ally, the native French-speaker Hamilton became Washington’s liaison with the French. As he spoke French with them, rivals labeled him a traitor for revealing secrets to these foreigners. It is easy to image Fox News mangling all this into one of its outraged broadcasts.

Burr and Hamilton crossed paths many times, first, in the Continental Army, where Burr served a general who hated George Washington and all who served with him, a hate the good subordinate Burr internalised. They were also thrown together after the war in legal studies and in their careers in law. Though neither was important enough to the other to figure in any of the surviving letters from that period. Later when Hamilton bought a house in New York City, Burr was the conveyancing lawyer for the vendor.

Perhaps because of his background, Hamilton tried to be more of a gentleman than anyone a gentleman by birth. Ergo he was ever alert to insults and slanders, and challenged to a duel more than one person he perceived to have slighted him. The first few of these challegenees declined the honour. Washington himself rebuked him for doing this, supposing there were more pressing matters at hand.

While he was de facto chief of staff for General Washington, his official capacity was an aide-de-camp, a messenger, and the highest rank he achieved was lieutenant-colonel. As an aide-de-camp he could go no higher. Ambitious as he was, and sure that the war would end in a British defeat, he wanted to rise higher, and left Washington’s service to seek a field command in order to do so. There was a rupture of sorts, though each regretted it and said so, but Hamilton got a command with the New York militia and played a decisive role in the final attacks at Yorktown, leaving the army as a full colonel and a reputation for success on the field of battle. His attack at Yorktown was coordinated with the French army there, and proved to be the end.

He married into a wealthy Dutch family but strove always to live off his own meagre income, as a soldier, public servant, lawyer, and author. That was not easy and his wife often took the children back to the paternal estate on the Hudson River.

Washington made him Secretary of the Treasury and he worked like a demon to make the USA a viable economy, through a sinking fund, a national debt, debt consolidation, the mint, the dollar, the reserve bank, tariffs, customs, and more. He won compliance from the states by assuming their debts from the Revolutionary War. Somehow he found time to ease Vermont’s secession from New Hampshire and entrance into the Union as the fourteenth state. He worked twenty hours a day for many stretches, far more than any of the clerks employed in the Treasury who arrived at work each day to find trays full of directives, orders, draft letters Hamilton had written overnight. At one time he employed twenty-seven clerks exclusively working for him.

Though a native French speaker, and an admirer of French writers and fashion, he foresaw ‘the special relationship’ between the United States and Great Britain and worked at repairing relations with England, first through commerce and later through some unofficial diplomacy, which aroused the animosity of the French lobby in the person of Thomas Jefferson.

During the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800), President Adams commissioned Washington as Commander in Chief who appointed Hamilton a major-general. Since that war was mostly maritime, Hamilton bent himself to enhancing the US Navy and together with President Adams he can be credited one of its chief founders.

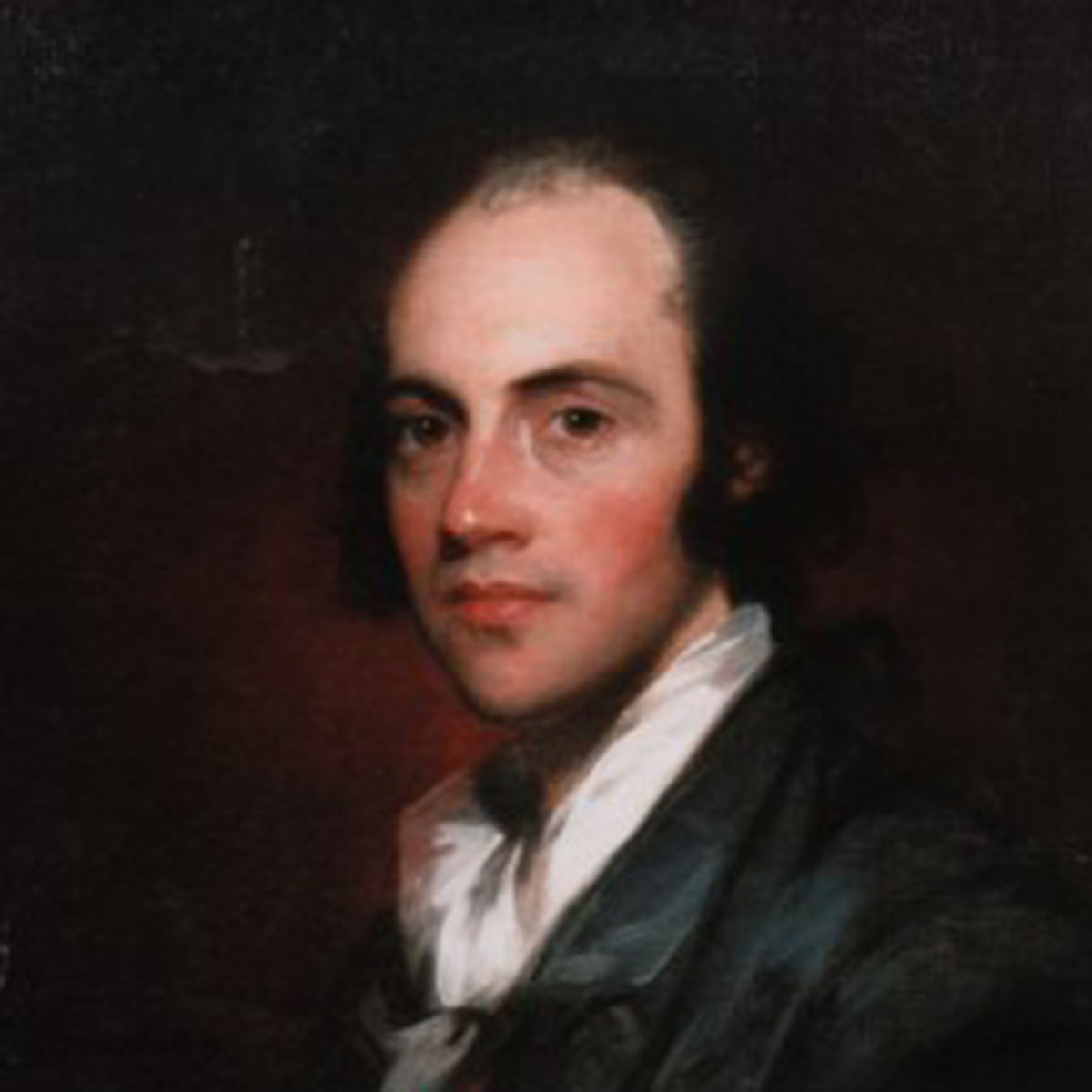

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Hamilton was never much of a husband to Betsy, the shy, retiring, insecure, hesitant, ill wife who bore him five children; he preferred the company of her vivacious, extroverted, well-read, worldly sister Angelica, but there is no reason to believe it was sexual. But he was putty in the hands of a pretty face. When Benedict Arnold bolted, Hamilton believed the lies told by Mrs Arnold, and gave her money, which she promptly used to bolt and join Arnold. Later another woman seduced him and Hamilton crept around to her backdoor several times a week for eighteen months. Her husband then set about blackmailing Hamilton at the very time when John Adams was promoting Hamilton as a presidential candidate. Think Gary ‘The Zipper’ Hart.

The rumour mill worked overtime and finally Hamilton told all in a pamphlet to save his reputation as a public servant and the credit of the Treasury department, at the expense of his personal reputation. Hamilton then resigned. Despite more than twenty inquiries, investigations, trials no peculation was ever discovered. His wife found out of this infidelity by reading about in the newspapers.

But he could not leave public life, and campaigned in the gubernatorial election in New York state against Aaron Burr. Burr claimed Hamilton had slandered him at a private dinner party and challenged him to a duel, and killed him before he reached fifty.

I read Randall’s one-volume biography of George Washington some years ago and liked it.

Willard Randall

Willard Randall

There is no summing up at the end of the book, so here is mine. Hamilton was an economist avant le mot, one of the very few who realised the importance of establishing the financial viability of the new country even during the Revolutionary War. He had a great capacity for work in the best of the Puritan Ethics. Though many tried to blacken his name, including some heavy hitters like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, his personal probity was absolute. Hamilton was clear-headed and rational in argument, and in anger grew cold and slow, but he never seems to change his mind or accept compromise, though he had enough sense at times to leave the room rather than erupt in anger.

He rose to the occasion time after time and in different ways, first in arriving in the north America, then as a soldier, and then as an economist. He was inventive and no insurmountable task discouraged him. He also despised mobocracy or democracy. The state governments were democracies and to his mind they were irresponsible, corrupt, and incompetent and they would always remain.

But he also he also was putty in the hands of several women, at the expense of his wife, and one of those dalliances, which certainly was sexual, was his downfall.

In public life he made enemies easily, and often deliberately. He would name those who opposed his arguments as dunderheads. The wonder is that he was not killed in a duel earlier. Some of this seems to have been his intellectual arrogance. John Jay was his tutor in college, lent him money in later life, worked with him on the ‘Federalist Papers,’ but once when Jay differed from Hamilton he assassinated his character in print without hesitation.

This book is marred by non sequiturs that increase toward the end, and the story of his last years is truncated compared to the nearly day-by-day account of earlier years. That unevenness may reflect the paucity of sources, the fatigue of the writer, or the demands of the publisher. Whatever the reason, it is obvious.

By non sequiturs I mean passages like this: ‘Hamilton’s proposal was widely opposed. It passed easily.’ Huh? I had several of these ‘Huh?’ moments. There other inconsistencies. Early on Hamilton is said to be not attractive, and later he is said to be so. The goal posts seemed to move.

At some point it is said Hamilton advocated rights for women, but I had not noticed anything on that subject to that page, nor indeed after it.

I also found distasteful the opening of the book with the duel and his death. It makes almost no sense put first without the context of his life, if not his times. But it is lovingly detailed, the stroke of the oars, the colour of the coat, the shine on the pistols. I suppose this was the demanded by the publisher.

There are also some typos. This from Harper Collins.

‘The Murder of Mary Russell’ (2016) by Laurie King

Another entry is a brilliantly conceived and executed series featuring an ageing Sherlock Holmes and his bride, many years his junior, but nonetheless his equal. She had to be to displace ‘The Woman’ from Holmes’s mind. Baker Street Irregulars know who the ‘The Woman’ is. I am not sure that Mary Russell has yet learned about her in this series.

There is a lot to like about these krimis. There is energy, movement, period detail, and most of all the characterisations of Russell and Holmes but also others whose path they cross from the cantankerous Mycroft, to ingenious Billy Mudd, to the redoubtable Mrs. Hudson who has much up-stage time in this entry.

Much of this title concerns Mrs. Hudson’s past live(s) and even that of her parents (we are spared the grandparents) told in a novella within this novel on the order of a Charles Dickens novel of the dark, noisome, and sinister Victorian London, with a long side trip to sunny Sydney. All of this is well done but of no interest to this reader, and probably not to many others, who like this reader, follow the series for Holmes and Russell. I thumbed those pages quickly on the Kindle and there were a lot of them, a lot. Holmes does eventually make an appearance there, too little and too later for this reader.

However the action returns to Russell and Holmes and crackles when it does. I found Russell’s message to Holmes unfathomable. Nor did I follow the reasoning about the flight. But who cares, that is like quibbling about the colours on a racing bicycle as the rider drives it up L’Alpe d’Huez.

Laurie King

Laurie King

Mrs. Hudson has had her due in an another series, e.g., Martin Davies ‘Mrs Hudson and Spirits’ Curse’ (2005) and many others.

The conceit in this series is that she solves most of Holmes’s cases with her below stairs contacts but lets Holmes upstairs think he has done it on his own.

Eat the stupid?

Eat the rich!

How amusing. I saw this exhortation in a feed on Facebook. Everything old is new again.

When people say I have no sense of humour, they are right. I never had a sense of humour about the racist and sexist jokes either. When the racists and sexists tried the fig leaf of humour as a cover I did not relent. That was when I learned I had no sense of humour.

Adolf Hitler had the same idea about the rich. He had every last member of the Rothschild family that could be found, one branch of which owned a bank of that name, hunted down, imprisoned, humiliated, tortured, and murdered. They were rich. Very.

However, being a vegetarian, he did not eat them.

Some of the Rothschilds were incredibly rich and they all were Jewish after all. Hard to say which was the greater crime. They got rich, in part, because they took risks other bankers were unwilling to take, e.g., like lending money for the building of the Suez Canal. But more generally to lend money to other Jews because Christian-owned banks would not.

For what it is worth, the surviving Rothschilds stem from other branches of the family, some living in England who survived in that liberal-democratic society so despised by the people who exhort others as above.

No doubt, I will shortly be unfriended.

By the way, the Rothschilds remain a whipping boy for all manner of nutters on the internet. Adolf’s spawn.

‘Wolves and Angels’ (2012) by Seppo Jokinen

A krimi from the industrial city of Tampere (population 364,000) in the forests of Finland.

Winter in Tampere

Winter in Tampere

Detective Saraki Koskinen probes and pries, in between outbursts of temper. He is wound up as tight as the clichéd spring. Divorced, he combines workaholism with fitness fanaticism to fill in the hours. He jogs, well, races, at midnight or later and rides a bicycle everywhere, as fast as he can. Consequently, he sweats a lot and needs showers and clothes to change into, and these he carries. He is organised, but some things always go wrong and he is caught in embarrassing situations, which occasion outbursts of temper as compensation.

There is a murder victim, a paraplegic. Who would want to murder a cripple? Perhaps anyone who knew this bad tempered man, whose affliction just made him more aggressive and violent, having perfected ways to use his mechanised wheelchair as a battering ram, especially against people who underestimated him in that chair. In the assisted living home everyone has a bad word to say about him: Loud, noisy, drunk, violent, rude, inconsiderate at all hours, starting to sound like a teenager.

Then there is an a second victim, an elderly man who lives near the home but not in it, and who was near death from cancer. Then a third, another resident of the assisted living home, a woman whose paralysis was so great she could barely speak.

Are the three murders related? Are the three victims connected somehow? Are these perverted mercy killings? What does the perpetrator gain from the first, the second, and the third death? Is the second murder part of the sequence or a coincidence?

The novel is a police procedural and the squad interviews and re-interviews all the residents at the home, the visitors, the staff, the suppliers, and neighbours without getting traction. In the course of this members of Koskinen’s squad argue with each other about overtime, office supplies, and the assignment of duties. It is by no means a happy crew. Seldom can anyone say more than two words without interruption, or someone stomping out of the room in anger. Koskinen is not the only one wound up tight. As the leader he seems unable to calm them down.

Koskinen has yet another new intern as a temporary secretary-receptionist who cannot stifle the urge to rearrange his papers neatly. Her well-meaning but misjudged intrusions lead him to one burst of temper after another, which seem to wash over and off her. Just as well because there are more to come.

In addition, his team members bully one junior detective, and though Koskinen is dimly aware of it, he cannot figure out what to do about it, and being a man he cannot ask for advice. Bullying in this case seems to be an outlet for the frustration of the others vented on the weakest member of the group. The frustrations are about the case, about the malaise of the police service, about personal irritations, about anything and everything.

When some uniformed patrol officers forget to report the discovery of an abandoned wheel-chair, there follows another outburst of the well-known Koskinen temper. That the patrol officers forgot because they were involved in a particularly gruesome traffic death only slightly reduces his outrage.

After each outburst, he realises he is not in control of himself, wishes he had not done it, and cannot apologize. See, life-like.

Meanwhile, there is much about Finnish manners and morēs that I found interesting. But even more about the paraplegics and quadriplegics at the assisted living home, their ways of coping with life after paralysis, of finding satisfaction (food, drink, drugs, sex), and the relationships among them.

In the hope of a speedy resolution before the media hysteria leads to an intervention from Helsinki, the police chief points to an intruder as the likely culprit, but Koskinen, in the best tradition of the genre, is sure the villain is in the home or closely associated with it. Indeed.

Though that conviction is undermined by a close study of who had access and who has keys to the building. There is an official list for each, both short, and a real list, both much longer. On the real list are taxi drivers, prostitutes, delivery drivers, close relatives, medical specialists who hand the keys to locums, and more.

As is compulsory in the contemporary genre, there is much about budget cuts in the police but also in the assisted living home. There is no staff member in the home overnight but rather an elaborate electronic security system to monitor the residents and the building. The latest in IT. But in a crisis it signals a security agent who has a twenty-minute drive to get there, if the weather is good, more if there is rain, wind, or snow, as there is nine months a year. According this agent arrives too late each time.

Meanwhile, when not pedalling or racing, Koskinen sees television interviews with the national Police Minister talking about further budget cuts in policing, and outsourcing more and more police duties to contractors with such IT setups. This lifts his morale, not.

As always I find keeping track of such unfamiliar names a challenge, but the author very clearly distinguishes and delineates the characters and that helps a lot.

Seppo Jokinen

Seppo Jokinen

There are many other titles in this series featuring Saraki Koskinen in Finnish, but this seems to be the only one translated into English as yet. I do hope more are on the way.

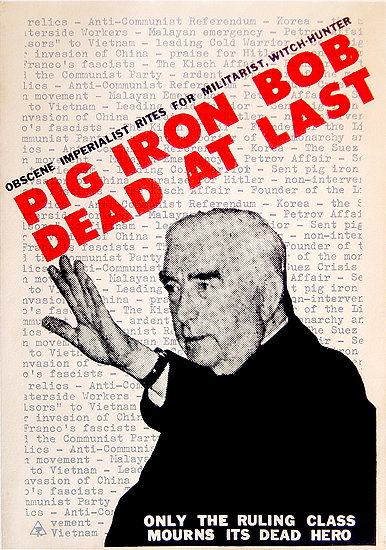

‘Pig-Iron Bob’

Every Australian of a certain age has heard this term, ‘Pig-Iron Bob,’ and knows what it means. I did, too, until I read Geoffrey Blainey’s ‘The Steel Master (1973),’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

[No comment.]

[No comment.]

As with so much common coin, the Vox Populi is exactly wrong.

First to the common interpretation. While Robert Menzies was Prime Minister, Australia sold pig-iron to Japan in the later 1930s which pig iron the Japanese turned into weapons to attack Australia. That is the claim, and there are many chest-thumping assertions about it on trade union web sites.

It is another myth, like the Brisbane Line. Never existed but became reality by repetition.

Let’s start with the basics. Pig iron cannot be shaped into weapons-grade steel. It is a by-product of steel production not the basis of it. Cause-and-effect can be tricky like that.

BHP did indeed sell that pig iron to Japan, that is true. It did so to prepare for war with Japan. Huh?

Essington Lewis, that remarkable man, who was CEO of BHP, foresaw a Pacific conflict with Japan as early as 1936, while so many of the Lefter-than-Thou persuasion were still toe-ing the Moscow line of friendship with the Axis powers. Lewis bore this message to all and sundry on his return to the wide brown land, but no one wanted to hear it for fear of provoking the Japanese. Softly, softly was the bipartisan foreign policy at the time.

Disappointed with the political response, on his own initiative he began converting BHP steel works to weapons production. While the board of directors chaffed at this unprofitable exercise, the chairman of the board backed Essington Lewis, and conversion went ahead full-steam, that being the only way Lewis ever did anything.

Lewis used the money from the pig iron sales to Japan to pay for this re-tooling of BHP factories to produced airplanes, ammunition, rifles, the Owen gun, Beaufighers, anti-tank guns, and ships.

In this way, the truth is that Japan paid for Australia to arm itself against its threat.

That phrase, like some other colossal lies in Australian politics, traces back to that tireless motormouth Red Eddie Ward. His admirers, a few of whom I have met, might also pause to consider that Ward also violently (but then he did everything that way) opposed home ownership, especially for the working class because it would sap their revolutionary fervour and delay the advent of Soviet Socialist Australia.

Fred Ward, Donald Trump is using his playbook.

Fred Ward, Donald Trump is using his playbook.

Pedant’s note. Grammar Girl advises that when a noun phrase is used as an adjective, it is best to put in a hyphen. Pig iron, the noun, becomes pig-iron the adjective. She is not alone. The redoubtable ‘New Yorker’ does the same. We village hicks but follow our leaders on this point.

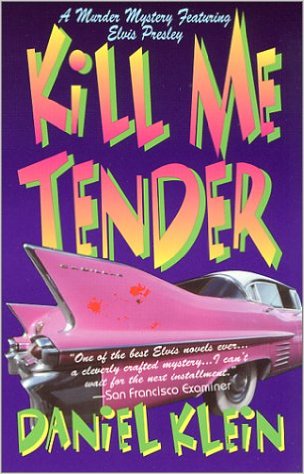

‘Kill me Tender’ (2000) by Daniel Klein

When the teenage presidents of Elvis Presley fan clubs start dying, the King notices, and the more he looks into these deaths, the darker they become. Looking is one thing, acting is another, and for that he mobilises his posse and makes an alliance with an unlicensed doctor, an African princess (well, that is how Elvis sees her), and himself in the person of an Elvis impersonator, and also the five-year old brother of one of the victims.

What a treat!

This Elvis is polite, considerate, compassionate, colour-blind, and tenacious. He has to be because he comes across some very rough customers in this tale. While he is used to being demonised for the evils of rock-and-roll, in this case it is literal!

His music is a bridge that spans some of the racial and social divides laid bare in his inquiries. Though he finds more in common with the poor blacks he meets than with the uptight whites. They both have Bibles to hand, but in the former case it is a comfort, while in the latter it is weapon.

When Elvis sings a hymn, well, who cannot listen, who is not transported, who does not believe the sincerity of his tears? Many, many, do believe, but not all starting with the very angry father of one of dead teens, who blames Elvis twice over, once for being white, and second for that satanic rock-and-roll. The first victim that comes to Elvis’s notice is black.

The upright, uptight whites are even more difficult to fathom behind a facade of Calvinist politeness. While they accept their daughter’s death as God’s will, they do not accept Elvis intruding into the matter. But he cannot stop himself. These children had somehow connected to him and now they were dying. Was it because of him?

As for the local law, as much as they suck up to the King, there is no interest in stirring. Well, except for one sheriff who sees big headlines in arresting Elvis for these very crimes. The plot thickens.

Into heady brew comes a criminal psychologist. Elvis has thumbed through her book without much comprehension but he then telephoned her. That conversation in itself is worth reading the book. ‘Hello, this is Elvis Presley….’ Then there is Elvis’s huge, tattooed, menacing cell mate when the aforementioned sheriff arrests him who styles himself ‘The One.’ He seems to have more insights than even the glamorous New York psychologist who arrives (book contract in her brief case, suspects Elvis) to lend the King a hand.

When the going got tough, Elvis’s posse was more trouble than help, and he finds strangers more help than those on the payroll, including some of the jailbirds.

Elvis was a class act and this book vindicates that in spades.

The book offers a very sobering and painful account of the life of a celebrity like the King. He is a prisoner of his frame. He cannot walk down the street, drive his car to a park, visit a cemetery, book an airplane ticket in his name, or go to church. If he does, he is mobbed by fans and the media. HIs every move in public is splashed across the headlines and talking heads start yakking.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Warning! Musings follow.

This Elvis reading got me thinking about the impersonators. Why Elvis? Why Elvis and not … [fill in the blank]. Why are there hundreds, thousands of Elvis impersonators from Malta, to Tallinn, to Montgomery? Why are they still at it now, thirty-five years after his death?

Of course there are impressionists who imitate Madonna or Brad Pitt on a TV skit. But none of those idols have the army of global impersonators that Elvis had and has. And that is the point, anyone can be imitated and many are. But why is it only the King with such an army of autogenetic impersonators? (Well, maybe not Brad Pitt since he has no personality to mimic.)

A few years ago we saw an exhibit of photographs from the early years of Elvis. The overall impression was a modest boy struggling with the demands the world was just beginning to make on him. Particularly arresting was a photograph of him walking home from the train station after his first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, a young man in blue jeans and shirt sleeves, like every other one, waving goodbye to those still on the train.

On my pilgrimage to Graceland, three things impressed me.

One was the music. It was everywhere.

The second was a video that included Elvis backstage in Los Vegas toward the end, saying ‘I am so tired’ in a voice that left no doubt that he was very tired, but the show had to go on, and off he went, in that grotesque white jump suit.

The last thing was the line of people, men and women in the shop, European and Asian, who queued up to have a photograph taken with a holograph of Elvis. Ghoulish. The King still has no rest from the rapacious appetite of the fans.

Illegal immigrants, indeed.

Here is some food for thought, were that possible for the Donald Trumps (and Peter Duttons) of this world.

Who is the most famous American illegal immigrant?

There are many candidates, but have a look in the wallet, bleaders in the U.S.A. Got a ten spot? Look at Alexander Hamilton. He is one of the finalists.

First, why is he on the ten, and then how did he get there.

He is on the ten because he created the United States currency. He devised the reserve bank system, coinage, paper money and a lot more. A founder indeed. (He was also an artillery officer in the Revolutionary War, more military service that Trump has seen.)

Until he was murdered, it was widely supposed Hamilton would succeed George Washington as leader of the Federalist Party. It was Hamilton who first bruited the Washington Monument.

Hamilton was also an undocumented, illegal immigrant born out of wedlock to a French mother on a Danish island in the Caribbean Sea who entered America at age eighteen. What a trifecta. Moreover his maternal language was French. He learned English as a teenager at a Jewish school and from the Dutch businessman for whom he worked.

What would Trump or his local imitator Dutton make of that?

A voodoo frog on a bicycle and a bastard to boot. Literal in the case of Hamilton and figurative in the other cases.

The Foxy rapprochement – beat me by a day

The closer Donald Trump gets to the Republican nomination the more the media, other Republicans, and some Democrats will discover his virtues. It is always the same, every four years the cycle is repeated as though for the first time.

Earlier in the campaign qualities deprecated and ridiculed in a candidate, will come to be accepted and then celebrated as positive.

For example, inattention to facts will transform to strategic thinking, untrammelled by petty details.

For example, flippant and destructive remarks, will be transformed into suggestions, and trial balloons.

For example, hostility to Hispanics, refugees, Muslims, women, left handers, homosexuals, will become — thanks to the alchemy of opportunism — unifying remarks.

For example, vague and diffuse threats to other nations will become, presto, disguised diplomacy.

The media always leads the way in this prostitution. When it seems a candidate is going to win, the realisation follows that an accommodation will have to be made with the candidate to keep manufacturing the news.

Even a big target like Trump will get the benefit of this self-censorship. Indeed, the more he threatens the media, the sooner some of its representatives will fall into line in the hope of securing favours before others comply. When it comes to self-serving opportunism, no one can beat Murdoch’s organs.

Soon there will be a rapprochement between Foxy News and The Donald. ‘You read it here first!’

Other Republicans will accept their own candidate, no matter what. All the posturing and playing hard to get will evaporate when success looms. The office seekers ever so subtlety seek office with more finesse than Chris Christie.

Then there will be Democrats who see Trump’s pull in their electorate, and have no wish to rile voters. These are the ‘If I keep quiet maybe their will not notice my party label is Democrat’ leaders. Some of them will couch their campaign publicity to omit the very word ‘Democrat.’ such leaders as they are.

Jimmie Carter went from ‘Jimmie Who?’ to a sage in this kind of transformation. Ronald Reagan’s habit of falling asleep in meetings, became a cool detachment. John McCain’s long past use-by-date became maturity. Mitt Romney’s narrow sectarianism became a virtue.

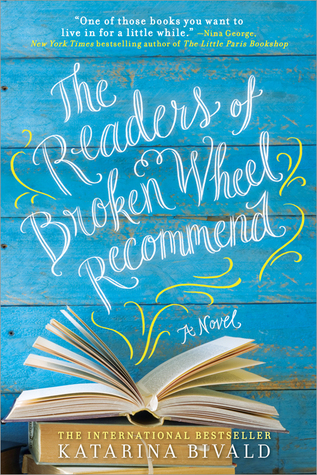

‘The Readers of Broken Wheel recommend’ (2016) by Katarina Bivald.

Chick Lit and I want more of it!

A delightful account of the culture clash between a single Swedish tourist who comes to Broken Wheel, Iowa, population 640 and declining. Sara is her name, and though she is classroom fluent in English the Iowa accents and idioms do not readily translate.

The good citizens of Broken Wheel are delighted to find a tourist in their dwindling midst. Sara left Sweden because there was nothing there for her, and she is pleased to be warmly welcomed.

Sara, however is nonplused, because her pen-pal and prospective host for the stay in Broken Wheel, Amy, is nowhere to be seen. She and Amy have been corresponding about books and life for a long time. The absent Amy has left instructions that Sara should stay in her house and make use of her books. She does.

Caroline runs the town by the force of personality. Formal positions mean nothing, and in the end that pays off, but not before this pillar of rectitude learns herself of sin first hand. Wow!

Jenn chronicles it all in her newsletter, blog, and private diary. Grace observes with disdain, a shot gun at the ready. The Grace women are always armed.

George stays off the drink one day after another, that is, until his long lost daughter returns, and then leaves again. The second loss is too much for George.

Andy and Chris pull the beer at the tavern, and the six hundred residents accept this gay couple without a word.

Cornfields play a part, too, because after all it is Iowa; there are a lot of cornfields, but none as scary as the one in the first episode of ‘Star Trek: Enterprise.’

Spot the Klingon.

Spot the Klingon.

Then there is handsome Tom who cannot help noticing the new face in Broken Wheel. He is too handsome for her, and she is too smart for him, but, well, in books anything can happen, right Mr Darcy?

Then Gavin the regional representative of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service appears. Gavin hated his old job in the USCIS because he had to arrest and deport hard working, god-fearing, polite, resigned, clean, and illegal Mexicans who never complained about how badly they were treated.

His remit is now Europeans, and Sweden is in Europe, right? Europeans, these he is ready and willing to arrest and deport for the slightest infraction of visa rules. If only…

Gavin descends on Broken Wheel with the full might of Federal government at his disposal, and finds that he is overmatched against Caroline.

Katarina Bivald

Katarina Bivald

To give the devil its due, I noticed this comment on Good Reads

‘This book was absolute rubbish. 394 pages of stupid observations written in a clumsy and somewhat childish language combined with unbelievable characters.’

A salutary reminder of why I do not bother with Good Reads.