This krimi is the first of three involving Professor Maureen ‘Red’ Solaris in a college’s school of journalism. The dean of the school has died in a fall down some stairs over the weekend, Did he stumble or was he pushed?

There are many tensions within the school. The Old Guard is mortally jealous of its ancient privileges and prerogatives which the dead dean was eroding in reorganisations. Disappointed and disaffected candidates for tenure seem to be bent on destruction. Meanwhile, among the students, blackmail might be the route to an A+ result. Then there are the sexual assaults, divorces, and alcoholism. All and all, it sounds like a typical department. The only things missing, I thought, were embezzlement and extortion.

In fact, I found it all so real that flipped the pages, it being too much like being back at work: The special pleading from junior faculty, the one-eyed demands from senior professors, the requests of students for yet more concessions. If I wanted that, I could go back to work. It all seemed plausible, but that did not make it any more diverting to read. The only unrealistic element was the consideration and support offered by the corporate management at the top of the college to the beleaguered acting dean.

Professor Solaris is designated acting dean, and becomes involved in the snail-like police investigation. She then confronts the many psychopaths among the faculty and sociopaths among the students. At some point, I said a plague on all their houses.

Flipping the pages was made easier by the rather self-centred telling. The author identifies completely with Red and it shows. Her thoughts are cherished. Her love life sends quivers through the pages. Her fastidious habits are detailed. Oh hum. To this reader all of this was self-indulgent padding that advanced neither character or plot.

Bourne Morris

Bourne Morris

Not rushing to try volumes two and three, I am afraid.

‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (1992) by Sharyn McCrumb.

After reading her ‘Bimbos of the Death Star’ it was only a matter of time until I got around to ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool.’ When my Amazon Wish List came true on Christmas the time was right. It is an amusing and diverting lark as literati Marion and engineer Jay combine forces once again to get to the bottom of a mystery.

When frail Professor Erik Giles asks Assistant Professor Marion Farley to accompany him to a private reunion the fun begins. Jay Mega goes along to ride shotgun.

It is a very special reunion of a select group who were nutcase sci-fi fans in the distant 1950s. In the ensuing forty years some have made it big in books, in movies, in life and others have remained adolescent into old age.

The lore of fandom and tales of conferences past, the parade of sci-fi names, this book has it all.

Then one of the reunionist dies and the plot thickens. The old tensions and rivalries in the merry band emerge perfectly preserved in the amber of time. Secrets, long held and forgotten by some, seep out. Not good. The death was murder. Who done it? That is the question, Mr Spock, and the duo get to work on it tout suite.

With the schizophrenic Mistral leading the pack, along with the semi-comatose Surn, and the one-man avalanche Woodard, the phlegmatic Angela, the absent Earlene, lawyer Jim, the author has assembled a mix of folks and stirred the pot. The plotting is simple but clever, the dialogue sharp, and the setting vivid. Would that I could say even one of those things about most books.

The major theme is the disjunction between the expectation of fans and the reality of writers.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

There is one glitch: when the hotel manager thinks of the death as murder long before that has been established on page 175. He of all people would certainly has assumed that the old coot died of natural, old-coot causes.

The book has pace, place, and plot. Four stars.

Spoiler Alert! There are no zombies. There were not any bimbos either.

‘McGarr and Sienese Conspiracy’ (1977) by Bartholomew Gill

This is an early title in a long running series.

It is model of composition and structure, covering a vast amount of territory in few words.

A body is discovered in far Dingle at the southwest tip of Ireland, trussed, drugged, and shot in the head like an execution. McGarr travels from Dublin Castle to investigate. Only two days later, while the usual inquiries are underway, a second body is found in the same place, the police tape and seal having been ripped off to dump a second dead man, likewise trussed and shot.

McGarr takes this second murder as a personal affront.

The victims were both English and that takes McGarr to London. The prime suspects are involved in oil expiation off the Scots coast, both Italians with ENI, and that takes McGarr to Italy, and eventually to Siena.

The characterisations are vivid, the travelogue nicely done, and the dialogue credible.

To this reader there is too much of McGarr musing on the English and the Italians. Too much description of clothes and food in both places as well as Ireland. All padding which does little, if anything, to establish either place or character. Too much to’ing and fro’ing. And it is beyond credibility that police in England and Italy defer to McGarr like a demigod.

I would have much preferred more of Ireland. For Italy I can read plenty of Italian krimis which will be mercifully shorn of musing on Italians.

The denouement was pretty obvious and so contrived as to be boring. The involvement of Foster, the Jamaican, seems gratuitous. The helicopter flying woman is another red herring too far. Just by coincidence she flew nearly the same route on the same days with one of the same passengers, who seemed to be two places at once.

Bartholomew Gill

Bartholomew Gill

McGarr also muses about several women, and this, too. I found a distraction, all rather adolescent. One of these women, later in the book, is called not once but two or three times by the first name Graham. It is a typographical error, that being her husband’s name. Talk about distracting. I thought at first he had come back to life. A sentence that contains ‘she Graham’ should have alerted any proof reader.

Michael Booth, ‘The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia’ (2015)

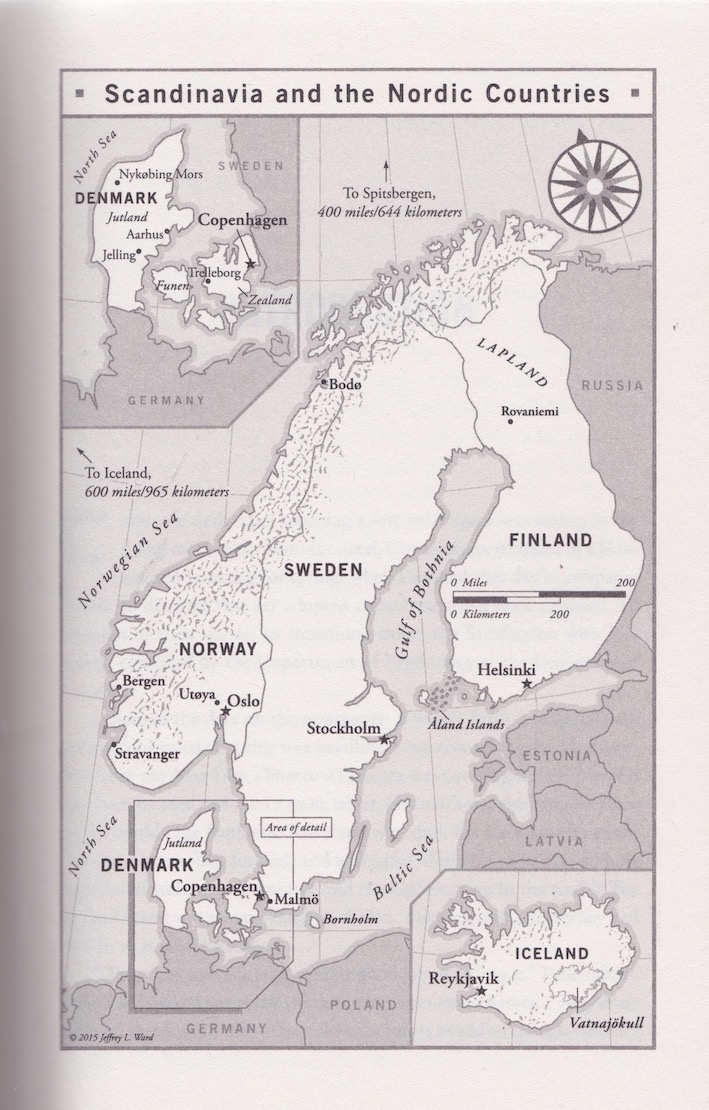

An amusing but informed, insightful, critical, positive, and biting though sympathetic tour through northern Europe. It starts with the definitions: no single term — neither Nordic nor Scandinavian — quite fits the combination of Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. ‘Northern Europe’ as a geographic term does not quite fit either, after all Iceland is way out there in the Atlantic all by itself.

‘Scandinavia’ does not include Finland, which has not participated in the Nordic Council and not in the Scandinavian Air Service, or NATO. As individual Finns are loners, so is their country. While the languages of the other four have much in common, not so Finnish. The Finnish language takes a lot of explaining, though grammatically it is, Booth says, simpler than most. It does not matter, since Finns do not use it much. He offers many examples of their taciturn nature. They are not the talkers that the Irish are. Their own term is ‘sisu’ which means just get on with doing it.

Iceland is the smallest, the most remote, the poorest, the most intimate, and all of that explains what they do and what happens in Iceland. There are a few snorts for reader when Booth samples some of the delicacies of Iceland’s cuisine. Iceland has long been very influenced by the United States and Great Britain, out that all by itself.

His analysis of Sweden as a mass society, my term, not his, has given me some food for thought. The explanation of the Swedish welfare state is that it makes individuals autonomous, i.e, they do not depend on each other [but on the state, yes]. Women are independent men; wives of husbands; children of parents, and so on. It is a benign decomposition of the civil society. What came to mind was William Kornhauser’s ‘The Theory of Mass Society’ (1959).

Norway? One word: oil. The wealth of the North Sea oil, despite the restraint exercised, has changed Norway and Norwegians, who now employ Swedish guest workers who peel bananas for them! Historic revenge against the colonial power! It is all explained in the book. See for yourself. The other distinction of Norwegians is their commitment to and engagement with the forests, fjords, and mountains of the country.

Denmark, where the author lives, is the odd one out. Perhaps because the author knows it best and he sees through many a veneer and what he sees, notwithstanding his efforts to balance the books, is not very pleasant. The courage to run that cartoon seems to have been born of a casual and still socially-acceptable racism, which often directed against migrants of any kind with the enthusiasm of a Tony Abbott. While successive Danish governments have been careful with the Kroner, Danes have not. The country has the largest private debt in the world, and its people work the fewest hours, and on every comparative measure of productivity rank low. It all seems rather fragile.

One of the strengths of the book is the use the author makes on the factual data available, e.g., to explode the myth, which I saw repeated just this hour on Facebook, that migrants are responsible for all, most, or any crime in Sweden.

He also makes good, though not systematic, use of the international comparative indices compiled by the Organisation for European Cooperation and Development, the United Nations, and non-government organisations.

The book seems to omit any account of the natives of the northern tip of the north, the Suomi peoples. They are mentioned but that is that. Who are they? How do they differ, how did they differ from Finns or Norwegians.

While Finland’s role as a buffer state, like Thailand between British and French colonies in Nineteenth Century south-east Asia, is treated, not much is said about Norway’s border with the Soviet Union and now Russia. Throughout the Cold War, Norway was the only western European state with a border on the Soviet Union.

There is no effort to define ‘utopia.’

Michael Booth

Michael Booth

The book is a salutory counterpoint to the personal reflections on Sweden in Andrew Brown’s ‘Fishing in Utopia’ (2009).

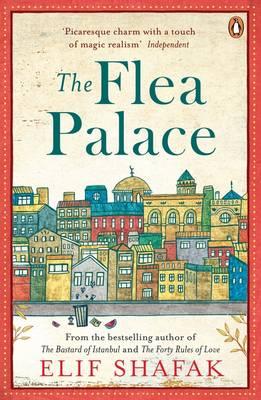

Elif Shafak, ‘The Flea Palace’ (2004).

Another item from my reading list for Turkey is this novel of 440 pages. It is well written and offers a cast of characters which represent some of the variety of life in Istanbul. There are many incidents, some great and others small, from the modus vivendi, so to speak, of the half-Moslem and half-Christian cemetery, the vanishing garbage, and the eponymous fleas. It is lively and, yet, well, I grew to resent having to spend my time reading it when I had such other alluring titles as ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (a treasured Christmas present from Herself) jockeying for my attention from the bedside table.

Despite the above remarks, there is no momentum in the novel. I was never quite sure why these characters were there and why I was supposed to invest interest in them. The assembly seemed to be arbitrary. Nor did I feel that, page-after-page, I was learning any more about any of them or the circumstances in which they lived. Instead the fevered imagination of the author produced yet another incident, twist, turn, upset, but well, since the prose was not going anywhere any twist or turn is just another twist or turn.

In so far as I got anything from it, it seems another exercise in ‘What does it mean to be Turkish’ that I found in ‘The Time Regulation Institute.’ Well do I remember all those talking heads on the CBC talking about ‘What it means to be Canadian.’ Same script here but different words. As Canadians have defined themselves by what they are not: American, British, or French, so some Turkish writers define Turkey by what it is not: European, Asian, Christian, Islamic. Not sure what the point is? Neither am I. Saying what it is not, does not leave what is.

I looked for other reviews to see if I had missed the point – it does happen. No professional reviews came to light and those I consulted, reluctantly, on Good Reads were, as usual, more about the reviewer than the book. Some liked it, but them some people like being hit with a stick. Others confessed that they had not finished it; my kind of readers, because I stopped, too. I am however grateful for one such reviewer who offered the summary below.

To make that summary meaningful I should say that the novel describes the live, loves, troubles, triumphs, lice, garbage, hair styles, reading habits, drapes of the assorted residents of an apartment building long past its prime, after an account of how it came to be built. The inhabitants who figure in the story are:

Flat 1, Musa, Meryem, and Muhammet: Musa and Meryem are married, but Musa is often absent. Their son is Muhammet who is a bullied at school, much to the distress of Meryem. Musa is no help.

Flat 2, Sidar and Gaba: Sidar lives with his dog, Gaba, and is obsessed with death.

Flat 3, Hairdressers Cemal and Celal: Separated as children, these identical twins are temperamentally dissimilar Cemal, who grew up in Australia, is a fussy extrovert, while Celal, who remained in Turkey, is painfully introverted. After reuniting, they run a hair salon on the ground floor whose staple is gossip about the occupants of the building.

Flat 4, The FireNaturedSons: This is a dysfunctional family dogged by ill fortune which tries to insulate itself from the others and, by extension, the outside world.

Flat 5, Hadj Hadj, his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren: Because the son and daughter-in-law work, most of the action in flat 5 involves grandfather Hadj telling his grandchildren stories which bore the oldest and confuse the youngest.

Flat 6, Metin Chetinceviz and HisWifeNadia: Metin isn’t around much, but HisWideNadia is: she’s a Russian émigré with an unhealthy obsession for bugs and a dubbed Latin American soap opera, ‘The Oleander of Passion.’

Flat 7, ‘Me:’ The narrator is a recently divorced university professor who think he is perspicacious. [The author is also an academic.]

Flat 8, The Blue Mistress: She is a kept woman for a merchant, which the neighbours accept despite the teachings of the Koran.

Flat 9, Hygiene Tyijen and Su: Hygiene is a compulsive clean-freak. Her daughter Su has lice, and that drives Hygiene to new heights of cleanliness.

Flat 10, Madam Auntie: The aged matriarch of Bonbon Palace, whose story only reveals itself towards the end, or so it is said. I cannot confirm this assertion since I ended my reading before the book ended.

The author has many other titles. Ahem. So be it. She also proclaims a PhD in political science. [Sounds of silence.]

More on ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ later!

‘Decision at Sundown’ (1957)

Here I am again with another Randolph Scott western movie. This time he plays against type, though it took this viewer a while to realise that. The certainties of the western genre are used as a foil to go further and to go deeper.

Bart Allison (Randolph Scott), is slowly revealed to be a crazed obsessive who stubbornly persists in his destructive ways against all evidence and reason.

Moreover, it is also against genre since westerns invariable take place before a background of wide open spaces. Not so here, where nearly all the action is confined to one cramped interior.

But wait, there is more! It is also against type in the portrayal of the villain, Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll). He certainly seems to have the town under his thumb, but he seems to have accomplished that with some greasy charm, a wad of dosh, and veiled threats, nothing more. As it turns out, the villain is not guilty of the heinous crime, Allison supposes, but Allison will not hear the truth nor accept that exculpation, not even from his best friend, Sam, played by the ever-charming Noah Beery, Jr.

Only later does Allison seem, at least for a few seconds, to realise his colossal folly, but even then he persists in his mad quest for vengeance. This is one of Randolph Scott’s darkest role, made all the darker by the expectations audience bring to his films.

The counter point to Allison’s moral disintegration is the gradual moral reintegration of the town’s people to throw off the yoke of Tate Kimbrough. Shades of ‘High Noon’ (1952), though the threat there was far more visceral and immediate.

The town doctor is a one-man Greek chorus who comments on the folly around him without getting involved in it himself.

In the end there is mano-a-mano shoot-out in the great tradition of the western, but this one has a surprise result. The last line of the film from the doctor says it all. See the film to find out about both the surprise ending and the last line.

The cast is full of familiar faces from 1950s television from the sheriff to the bartender, the barber, the banker, and more.

It offers lessons for film makers any time. In less than 80-minutes we have an ensemble cast, vivid scenery, much debate, some soul searching by both Kimbrough and Allison, violent death, and true love.

There are plot holes here. In the first scene, why is Scott in the stage coach, and why is it necessary for him to stop it with threats to meet his partner? Why could he not get a horse and ride to the meeting? Or why could he not arrange for the stage driver to stop at the locale he wanted, and just get off? Perhaps his threats to stop the stage are meant to indicate just how unreasonable he is to become later.

In the town of Sundown, how did Tate Kimbrough establish his hold? What about him led the decent and upstanding Lucy (Karen Steele) to want to marry him? (There is no affinity between them in a few scenes they share.)

‘Buchanan Rides Alone’ (1957)

Randolph Scott rides onto the screen with the confidence of a man who has emerged victorious in a previous fifty westerns, relaxed and confident. That slow and easy smile is knowing.

Tom Buchanan (Randolph Scott) is returning to West Texas to settle down, having made enough money in Mexico to buy a ranch. He re-enters the United States at the town of Argy. Big mistake. The town is owned by the Argy family, each member of which is more corrupt than the other.

Although the Argys are all stinkers, individually and collectively, they do not amount to much, and it is a foregone conclusion that Buchanan will best them.

Amid this venal bunch, there is Abe Carbo (Craig Stevens, before his ‘Peter Gunn’ days) who advises the Argy patriarch. Carbo seems to have some sense of honour that is not for sale, and becomes a neutral arbiter in the moral equation. Why the Argys tolerate him is a mystery.

The Argys steal Brennan’s swag while trying to lynch him and then to ransom a Mexican boy whom he befriended. The plot is disjointed with too much repetition and too little tension. The Argys have no honour among themselves and fall to bickering, first over Brennan’s stake, and then the Mexican ransom even before they get it. They end up killing each other. The body count rivals some of the riper episodes of ‘Midsomer Murders.’

Buchanan will ride on, alone, while Carbo will take over in Argy for the better.

The screen play has the Elmore Leonard touch in the dialogue, but not in the story line. There is a nice performance by L. Q. Jones as Pecos Bill. Did Craig Stevens ever play a heavy? That reassuring baritone of his is hard to imagine as menacing. The Internet Movie Data Base entry refers to him as a ‘light leading man.’ There I learned that he did dentistry at KU before the acting bug bit him. Sci-Fi fans may remember that he alone saved us from ‘The Deadly Mantis’ in 1957.

Unlike many of Scott’s other westerns there is no damsel in distress for him to rescue.

‘The Tall T’ (1957)

Psychopathic killer Frank Usher played by Richard Boone captures Pat Brennan (Randolph Scott) by mistake. Boone almost steals the show (with that hat he always seemed to wear in Westerns).

By a chain of incidents, each of which is unexceptional in itself, Brennan and newly weds Willard and Doretta Mims are kidnapped for ransom, well it is Doretta (Maureen O’Sullivan) who is worth the money. Her husband Willard is eager to sell her to the villains to save his own skin, a fact which the reticent Brennan does not reveal to her.

It is based on a story by Elmore Leonard; need I say more. It is terse, focused, and with depth. Within the conventions of an oater, it is a character study. Brennan and Usher are more alike than different. Loners and lonely, each too smart for the lives they live.

When Usher takes a cup of coffee to the sleeping Doretta and as he stoops to leave it for her, he pulls the blanket up to cover her better, well, that is some villain, isn’t it? That is an Elmore Leonard touch and Richard Boone is just the man to do it, that combination of menace and tenderness, as he, for a moment, realizes the life he has missed. It is a bittersweet moment passed in silence and seen only by the audience.

Doretta, who barely speaks in the first half, rises to the occasion with the encouragement of Brennan. To survive they have to out-think the villains.

Usher is ably assisted in his villainy by Billy Jack (Skip Homier) and Chink (Henry de Silva). What a crew of drooling half-wits! As we learn quickly they murdered a ten-year old boy for fun.

We know from the opening credits that the end will come down to Brennan (Scott) versus Usher (Boone) and that Brennan will prevail. Even so the tension throughout is well maintained.

And the final confrontation reveals the self-destructive — even self-hatred — of Usher. He has no wish to continue into the future the life he has been leading with morons like Billy Jack and Chink.

By the way, the title, ‘The Tall T,’ is never mentioned or explained. I supposed that it was the name of Brennan’s ranch, but that is nothing but a guess.

The same story is the basis for ‘Hombre’ (1967) and Richard Boone is there again, with that hat.

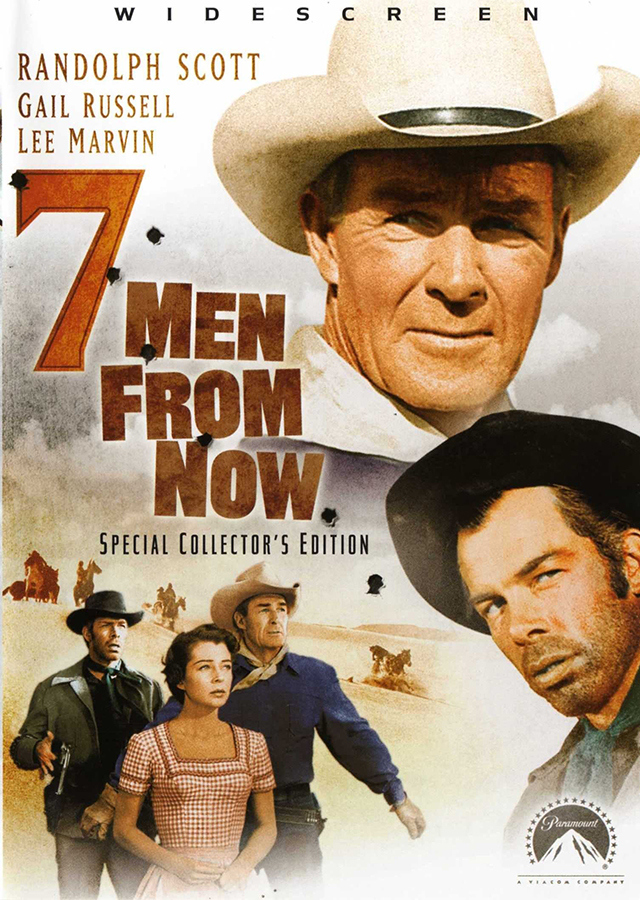

‘Seven Men from Now’ (1956)

Guilty secret number 71.

I learned much about manhood from Randolph Scott. Who? Randolph Scott (1898-1987), the movie actor. His westerns in the 1950s left an indelible imprint on the prepubescent consciousness of any boy who saw them and was conscious. This second criterion eliminates quite a few. Scott was everyman, whereas John Wayne was always much bigger than life. It was fun to watch the Duke, but no normal boy could aspire that high. Scott was so much lower key, he might live around the corner going about his business.

He was taciturn, honourable, persistent, and polite. For years I have toyed with watching the famous (in a quiet way, befitting his screen persona) seven films he made at the end of his career with Burt Kennedy (the writer) and Budd Boetticher (the director) in the Sierra Nevada mountains. I may have seen them each once upon a time, but the hazy ambition was to watch them in sequence. However, lacking the courage of my convictions I never got around to ordering them on DVD, and the local Civic Video did not have them or access to them. In any event the DVD collection on the market is incomplete.

Then came the miracle of You Tube and there I discovered ‘Seven Men from Now’ (1957). The candle was lit, and the next night I dialled it up.

When it was released in 1956 Scott was almost sixty years old. That was the year of Wayne’s greatest film, ‘The Searchers.’ and while the two movies share the conventions of the western there are differences. Let me see if I can put my finger on some of the difference(s).

It starts it the middle at a time when linear story telling was the dominant approach. At the outset Ben Stride (Randolph Scott) seems ominous, and even malevolent. Though the narration soon reveals he is a man on a deadly mission to find and kill the seven men who robbed a Wells Fargo Office during the course of which they shot and killed a clerk, this being Stride’s wife. Thus we have a tale of revenge. Seven to one against Randolph Scott. Don’t take the bet!

He kills the first two within five minutes of run-time. That is fast action. It also seems unjustified. Is not the good guy supposed to try to arrest them and take them back to jail, not provoke a gun fight?

While Scott pursues the villains, in parallel that wonderful heavy Lee Marvin pursues the gold they stole. From the second scene onward, we all know that in the end it will come down to Randolph Scott versus Lee Marvin at even money. Marvin’s villain has a certain vulgar charm and a great deal of intelligence; he is not ravening beast that villains are sometimes made to be. He makes a superb foil for Scott’s reticent decency.

There are some nice twists and turns, personal growth, and irony that is unspoken but revealed in the actors’ faces, all too subtle for the Hollywood hammer these days. Truth to tell, there are also some gigantic plot holes that I will pass in silence. Plot holes remain a common Hollywood currency.

While there are rumours of restive Apaches, these indians are portrayed as victims. The real evil ones are the robbers, and Lee, as he shows soon enough. There is an obligatory old-timer who adds a lighter touch to one scene with some self-deprecating humour. I suppose since Gaby Hayes the old timers are there also to show that a man can grow old in the wild west. The conventions of the western are honoured in this.

There is some marvellous countryside as the wagon (loaded with the illicit gold) rolls to its destiny. It has pastoral moments.

Through it all Scott utters very few words, but when he does, we all know he means exactly what he says, and says exactly what he means — not one word more, not one word less. We all also know he will do what a man has to do in a quiet, dignified way. Wow! What a guy.

By the way, the female lead, Gail Russell, had near-clinical stage fright in front of the camera, and dealt with it by drinking whiskey. She had the reputation of being unreliable and the director Boetticher, the wiki-gossip goes, made a considerable effort to coax her through her scenes and to keep her off the drink during the production. It was her first film in four years and one of her last.

John Wayne made many westerns but he did a variety of other films, while Scott more or less settled in the western genre and stayed there. He accepted and made his own the type casting of the strong, silent loner. Apart from his early career, and the war years, his film credits are westerns, westerns, and westerns, including some based on stories by that stylist of the sage brush, Zane Grey.

By the way, the main difference between ‘Seven Men from Now’ and ‘The Searchers’ is John Ford with his capacity for poetry, faith in the camera to show the grandeur of nature and the small size of men, irony, and even sense of humour. ‘Seven Men from Now’ is just much lower key, nothing mythic about it.

Next up will be ‘The Tall T’ released in 1957.

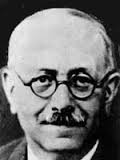

Marc Bloch, ‘The Royal Touch: Monarchy and Miracles in France and England’ (1923).

This book offers a study of scrofula. Scrofula was a swelling of the glands that medical historians say was a symptom of tuberculous. It was sometimes known as the King’s Evil. What do kings have to do with glandular fever? What is a ‘royal touch?’ The reader might bear in mind the concept of charisma when reading below. A few Google images of suffers of such glandular disorders will push aside any smirks about mononucleosis. In late medieval and early Renaissance Europe tuberculous remained an insatiable serial killer.

There emerged the belief that the king’s touch could relieve the swelling. It was the King’s Evil in the sense that it an evil the king could relieve.

Why, how, and where did this conviction emerge? How did priests, abbots, monks, and popes react to the king’s intrusion into spiritual mysteries? How did word of this miracle spread? What use did king’s make of this power? Did others try to capitalise on this belief?

Bloch’s research is meticulous into original sources reaching back to the Eleventh Century to piece together something of the puzzle. Prior to the Eleventh Century there is no evidence that European kings had the healing touch. Charlemagne’s (748-814 AD) rule is well documented and much storied, but nowhere in this record is there evidence of him applying this touch. If Big Chas did not do it, it is hardly likely any lesser monarchs were at it.

With Charlemagne’s death and his Lear-like division and subdivision of his realm among his inheritors and successors, the record are fewer and less reliable as Europe fell into endless conflicts. Through these mists we can see, thanks to Bloch’s pathfinding, glimpses of the royal touch documented from the Eleventh Century and thereafter.

The healing touch of some monarchs was well enough known for the afflicted to travel great distances to seek it, and remember that travelling then usually meant walking. Nor was the king’s touch applied only to his own subjects, for these records report travellers from other realms seeking the touch of a foreign king.

The surviving reports confirm that healing effect of the king’s touch. The swelling went down. The petitioner cried out in gratitude, and so on. The doctors of spin have always been with us.

Very often for every king there were a number of pretenders and rivals with royal blood. Did they, too, have, or have the potential for, the healing touch? What is the origin of this miraculous power?

Despite its success, the evidence that remains does not suggest kings made an effort in the first instance to exploit this touch to win over adherents in any way. Rather the touch is applied only on special occasions like a patron saint’s day or the Resurrection.

By the way, the king also gave the petitioner a coin. This monetary reward might also explain why some sought the royal touch so that they could touch the royal purse as well as be touched by the royal personage.

One such ceremony.

One such ceremony.

To some churchmen the king was intruding into religion’s domain of he supernatural with these miracles. Caesar was playing god.

How does the healing touch of a king relate to the divine right of king’s to rule? While God chose the king to rule, he himself is mortal, and has no line to divinity. That line is reserved for the ordained priesthood who sacrifice the material world. Yet later when monarchs wanted to assert their divine status, they would invoke scrofula and apply the healing touch,.e.g., Charles I of England in the Seventeenth Century.

Part of the evidence Bloch considers with his usual care is the descriptions of Charlemagne in ‘The Song of Roland.’ The poem came into European literature long after the death of Big Chas, and Bloch’s point is that it reflects the attitudes of the time of its composition, not necessarily of Charlemagne’s times. In it Charlemagne is a priest-king, giving blessings and making benedictions, wearing holy vestments as his Christian armies battle the infidel Moor. Hmm, never noticed any of that when I read ‘The Song of Roland’ as an undergraduate. But then again I missed quit a lot as an undergraduate.

Inevitably by the Fourteenth Century rival claimants to a throne and rival kings of conflicting realms sought justification in the supernatural. The healing touch was one of the fronts of these contests. But as Bloch notes, it seems that most of this conflict was in rival publicity. The kings did not have heal-offs, but their supporters circulated stories of their healing powers. Did the stories consist of whole cloth, or were they based on something? Bloch cannot be sure. What he is sure of is that they were believed by those who sought the royal touch, and the stories were credible enough for those who circulated them to continue to do so.

Churchmen, be they Protestant or Catholic, discouraged monarchs from the ritual of the touch on ecclesiastical grounds. Some of the advice was given privately and noted in diaries. Others ever so carefully denounced the practice in sermons – delivered or written. In addition religious figures involved in the upbringing of heirs-apparent indoctrinated their charges to disavow the royal touch. The most successful instance of this last indoctrination is James I of England, himself an intellectual, denounced the practice and yet did it. By the way Elizabeth I also engaged in the royal touch, laying hands on more than a thousand subjects on one occasion.

The same story unfolded in France. French kings were reluctant to do it, and were skeptical about it themselves, while they were discouraged for doing it by Catholic advisors, yet they did it.

Why?

Because their subjects wanted it. When notice was given that the king, whether in England or France, would appear at a church or cathedral to heal the sick, they came in thousands. When a reluctant king, when a king who accepted the advice of the spiritual advisors refrained from healing ceremonies, the populace became restive and the word filtered back to the royal ear that his legitimacy was in doubt. To the populace it was proof of the king’s divine right to rule that he could channel the heavens in healing.

More than one king confided to his counsellors or his day-books, the pressure he felt from this expectation, decrying the sick who gathered wherever he went, who followed his entourage into the countryside, who appeared in even the most remote location.

Those intellectuals who devised and thought out the divine right of kings, including James I himself, did not include scrofula in the equation. In fact because of the proscription of religious authorities were determined to preserve their own domination of matters spiritual. The king is chosen to rule, but that does make him divine. This fine print was of no interest to sufferers who flocked to kings for succour.

At times there were concerns about contagion and the king would not be exposed to roomfuls of plague victims. However to withhold the divine gift of the healing touch from those most in need, did not encourage loyalty in subjects. How could a divinely ordained king fear disease? Though the transmission of disease was not well understood, it was common for those with the means to do so, to leave an area when the plague occurred there. French kings travelled around the country, not to solidify their rule, but to find places without the plague. When watching one of the episodes of a television documentary on the stately house of England, say, the viewer is sometimes told that this king or queen once stayed there. That was probably a case of tourism inspired by the plague back in London.

The practice continued long into the Renaissance and even the Enlightenment. In 1715 Louis XIV, who was hesitant to lay hands on the ill, saw 1,700 in one day. Equally impressive figures survive in court records of other monarchs. None can best Charles II (1660-1684) of England in his twenty-five year reign touched nearly 100,000 of his subjects in such rituals. All the while the religious authorities looking on must have been grinding their teeth.

Kings in Austria, Spain, Bavaria, Anjou, and elsewhere claimed the healing power in pamphlets but seldom practiced it. Rival claimants for thrones began to offer to heal, once the crown went on.

All of this became entwined with other claims of divine preference. The origins of the fleur-de-lys which had been in use for generations were re-written so that it all but came down with the burning bush.

Political upheaval, Calvinist monarchs, rival faith healers, science, and the Enlightenment, these all combined to end the royal touch, as later medicine tamed tuberculous. The Hanoverians never practiced it, either in Germany or in England. The Calvinist monarchs in the low countries denied it even more vehemently. The Hapsburgs in Spain, the Netherlands, Bohemia, and Austria followed the advice of their Catholic advisors and avoided this blasphemous practice. Not even Rudolf II, that most unconventional of monarchs who dabbled in the occult, figures in the history of the royal touch.

The king’s touch was at its most potent when his accession to the purple was consecrated in a religious service, at Westminster for Brits and at Rheims for French. For in the beliefs of the day when the priest blessed the new king for a moment God’s will was manifest in the flesh. Talk about charisma! On those widely publicised occasions veritable armies of diseased petitioners would show up, along with the rich and mighty of the land.

Such records as there are show that some sufferers came repeatedly for the royal touch, plain proof that it had not worked the first time, the second time, or the third time. Some observers took the view that many of the ill came for the coin not the touch. Others, still more cynical, said that the petitioners were petty criminals who used the occasions as a pretext for pickpocketing and worse. Contemporary scientists, including some on the occult side of the table, tried without success to find an explanation for the effectiveness of the touch. Some physicians who were empirically minded kept track of those who had received the royal touch, and found… they died. The data was held in secret.

Yet the demand for the practice continued until monarchs were discredited and destroyed by political revolutions. Though Bloch is slow to accept it, the final explanation seems to be some kind of collective wish fulfilment, though that wording is more Freudian than his, which takes it to be an expression of a collectively unconscious need to assert control over the inexplicable and unknown, or even unknowable.

The book is 220-pages of text accompanied by another 220-pages of notes, appendices, descriptions of iconography, and citations. He wears the research lightly but it is impressive.

Marc Bloch wrote many fine books, including the magisterial ‘Feudal Society’ (1939) in two volumes which I read in 1974. It was one of the great books I relinquished when I moved from the Merewether Building.

Marc Bloch, who murdered in Paris in 1944.

Marc Bloch, who murdered in Paris in 1944.

My main source of medieval history is, of course, Robin Hood on television in 144 episodes from 1955-1960. This Robin Hood was the dashing and charming Richard Greene. I now realise a very young Paul Eddington was Will Scarlett in this series.

Postscript

Is the royal meet-and-greet when the queen, king, or prince(ss) walks through a crowd some vestigial echo of scrofula. People line up for hours for a glimpse of the anointed one, and the fortunate few in the front ranks may even still today with maxed security get a royal touch. Do those so touched feel better, elated, special, or something? They must, or to be more specific, they must think beforehand that they will, and so invest the time, energy, and effort to get that position in the hope of being touched.

It all fits with Max Weber’s conception the charismatic as one carrying a special grace, and the appetite of others to share in it by proximity or adherence.