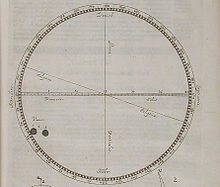

1639 Separately, Jeremiah Horrocks and William Crabtree first recorded the observation of the transit of Venus. It was a major contribution to mapping the Solar system.

1642 Dutch sailor Abel Tasman landed on Van Dieman’s Land, now Tasmania. His name is also on the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand.

1859 Charles Darwin published the ‘On the Origin of Species.’ A masterwork.

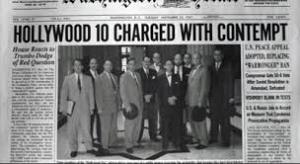

1947 The drooling monster HUAC ruled the Hollywood Ten in contempt of Congress. Several went to jail and at least one died there. The floor vote was 346 for and 17 against the citations. The Supreme Court later upheld the authority of Congress to so act. The ten were writers, directors, producers, and editors. It was a shot across the bows of the studios and interpreted in that way.

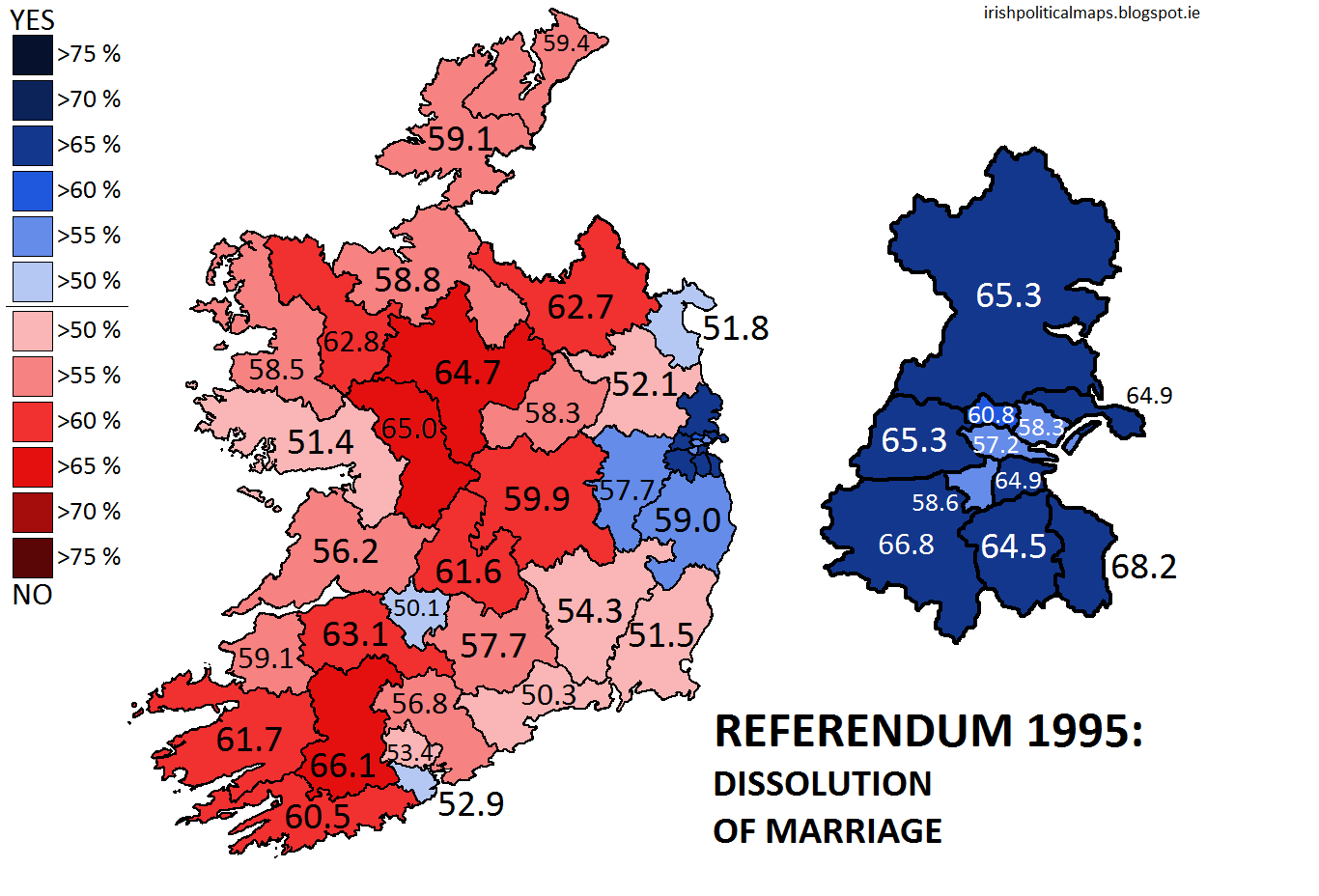

1995 In a referendum Irish voters accepted divorce 50.3 to 49.7, ending a 70 year proscription. In a total of 1.6 million voters the difference was 8,000 votes.

23 November

1227 The Spanish Christians drove the Muslim Moors out of Sevilla after a two-year siege. Been there. Those oranges perfume the air.

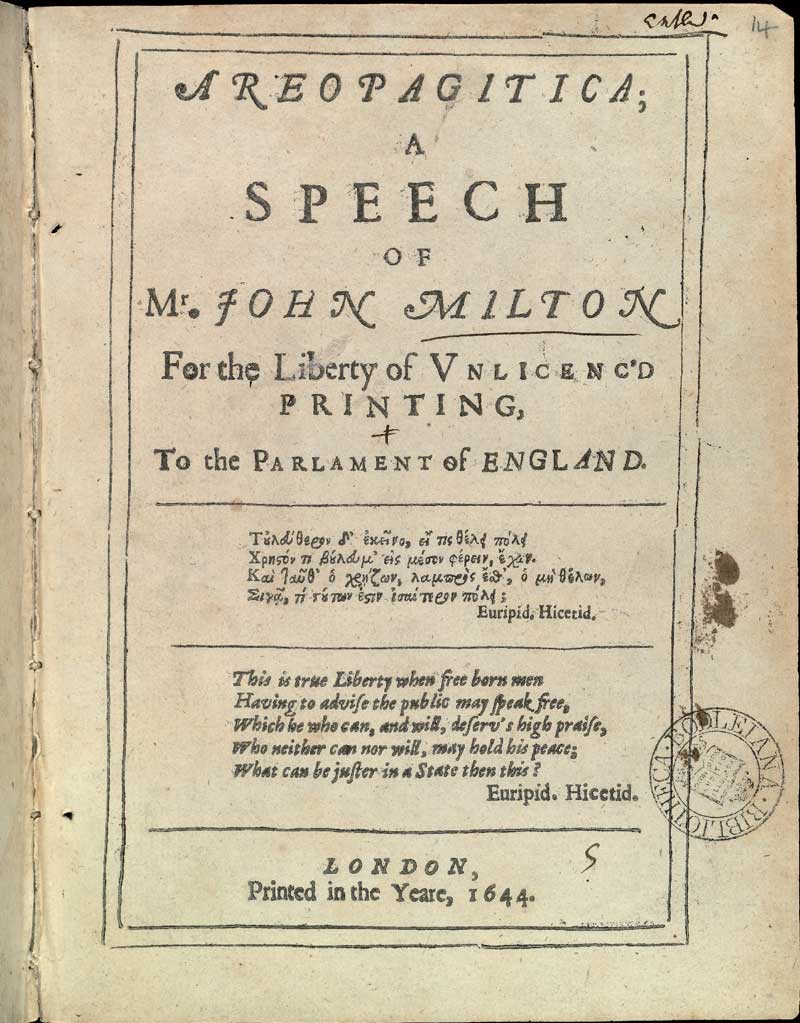

1644 John Milton published ‘Areopagitica,’ a polemical pamphlet advocating the freedom of the press at a time when there was none. Read some Milton but not this. Maybe I should.

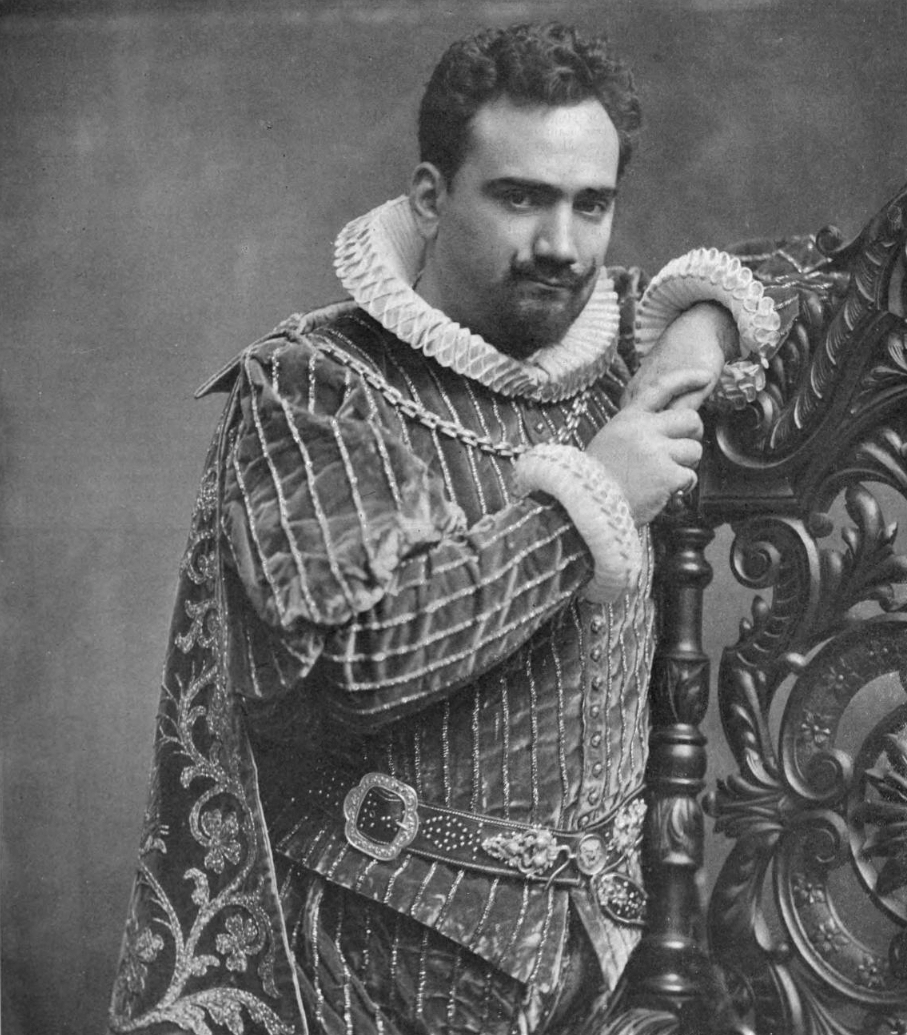

1903 Enrico Caruso made his American debut in Verdi’s ‘Rigoletto.’ Heard some recordings of ‘God’s voice,’ as Puccini said. Caruso in costume is pictured below.

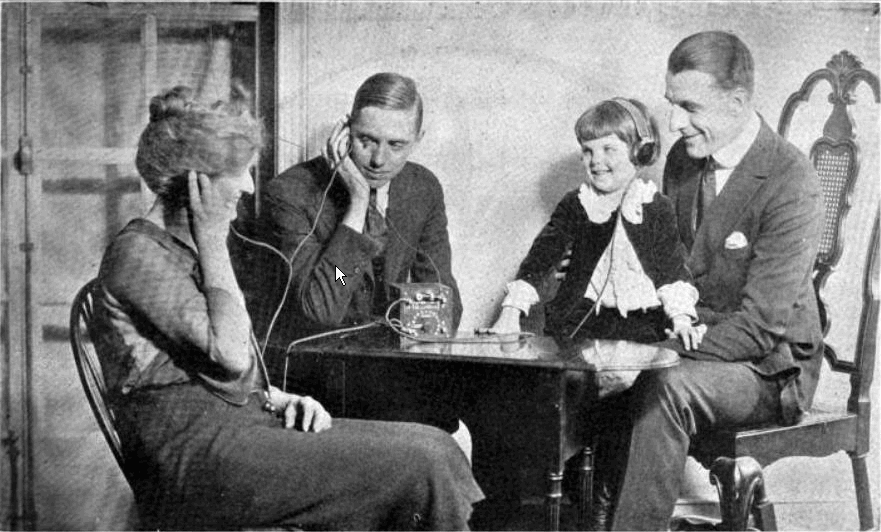

1923 2SB Radio in Sydney went on the air for the Australian wireless broadcast from Philip Street. SB = Sydney Broadcasters. It broadcast Saint-Saens ‘Le Cygne.’ Still going but has become ABC 702. N.B. that wireless includes plenty of wires then as now.

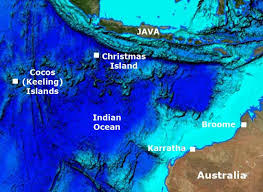

1955 Great Britain transferred responsibility for the Cocos (Keeling) Islands to Australia which with Christmas Island today constitute Australian Indian Ocean Territories closer to Sri Lanka and Indonesia than Canberra.

‘Out There’ (1995)

IMDb meta-data is runtime of 1 hour and 38 minutes, rated 5.5 by 270 cinematizens.

Genre: Sy Fy

Verdict: Charming.

Beau collects old cameras and finds in one exposed film from August 1969 which he develops in his home dark room closet. Whoa! It’s ‘Paul’ (2011) and his brother Asgards on film. Aliens with bulbous heads like ‘My Favourite Martian.’ What to do?

Well he is a free lance (aka unemployed) photo-journalist so he tries to sell the pictures. Editors dismiss them as fakes. He takes them to the Air Force where Chief Gillespie reads him the official word on UFO-riding aliens. Gillespie played the same bumptious fool in ‘Mars Attack’ (1996) discussed elsewhere on this blog. Do I see the hand of the IRS compelling this old stager on to the old stage, again and again?

Then Prince Nerd comes to his door with a thousand smackers for the pictures for his personal UFO collection. Bingo!

Beau soon discovers that Prince Nerd is a paid Liar, that is, he works for Faux News which has plastered the pictures along with Beau’s own countenance across the nation. Faux News blames the aliens on Hillary and this makes Beau a laughing stock.

Righteously indignant he goes to sock Prince Nerd where he meets Frail, who is the daughter of one of the men pictured with the aliens. Her dad and his pal disappeared that very night in 1969. She was there to find out what happened to Dad.

The two join … forces to figure it out. They meet a relentless real estate agent for whom ‘NO!’ is a bargaining gambit, an accordion playing retired football star, UFO nuts who begin to seem sane, some cagey trailer trash, and — well, yes — some aliens without bulbous heads. They read micro-cards, interview witnesses, explore dark houses, and find bright lights. That’s entertainment!

It is slow, low key, shorn of special effects, not a CGI in sight and relies on the droll script and the deft players to move things along. The direction gives it a gentle pace. Accordingly, mouth-breathers score it at 1 or 2 on the IMDb. Ah the benefits of a free public education wasted again.

Way over budget are some of the players, including Jill St John, Billy Bob Thornton, and Rod Steiger along with Mr Hom.

22 November

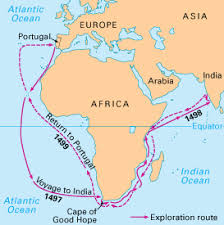

1497 Vasco de Gama (1460-1524) rounded the Cape of Good Hope bound for India. He was the first European to make this trip. Portuguese Empire in Asia began and then ended in East Timor in 1974. We saw replicas of his craft in the maritime museum in Lisbon. Yikes!

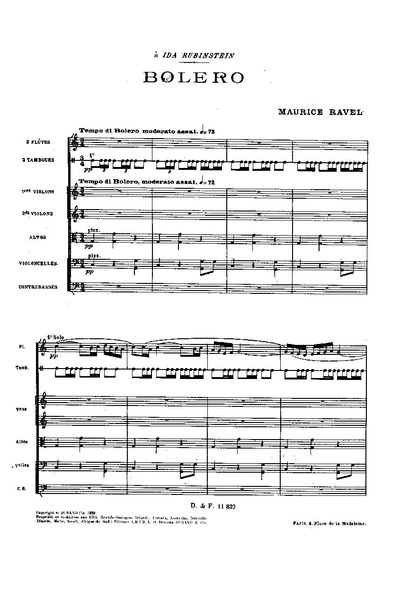

1928 Maurice Ravel’s ‘ Boléro’ was performed for the first time in Paris. the music remains instantly recognised. Commissioned by ex-patriate Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein; it was originally intended to be ballet and it was an instant success. It was soon used for dance.

1956 The Games of the XVI Olympiad began in Melbourne. Seventy-two countries sent 4,000 competitors with men outnumbering women 10 to 1. Because of Australia’s strict quarantine laws, the equestrian events were not staged in Melbourne, but rather five months earlier in Sweden.

1963 Jack was murdered.

2005 Angela Merkel became the Chancellor Germany and became a voice for calm, rationality, and the long view. She will be missed.

21 November

1620 Mayflower Compact established the principle of the consent of the governed at Cape Cod.

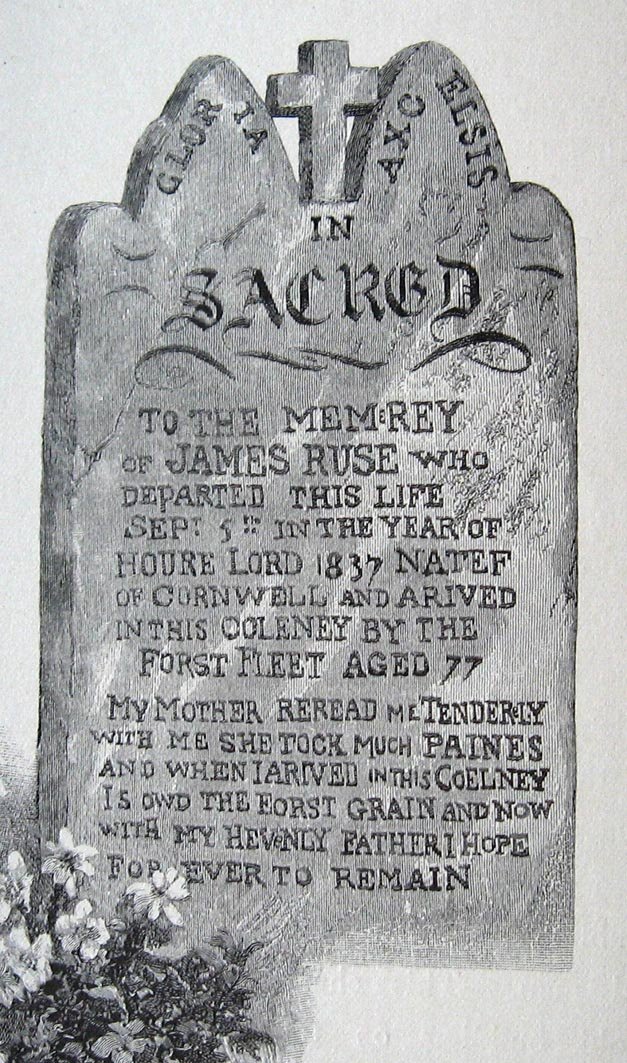

1789 Convict James Ruse received a land grant for an experimental farm in Parramatta. He was successful and got more land in 1791, and more. Now one of the best high schools in Australia is James Ruse Agricultural High School.

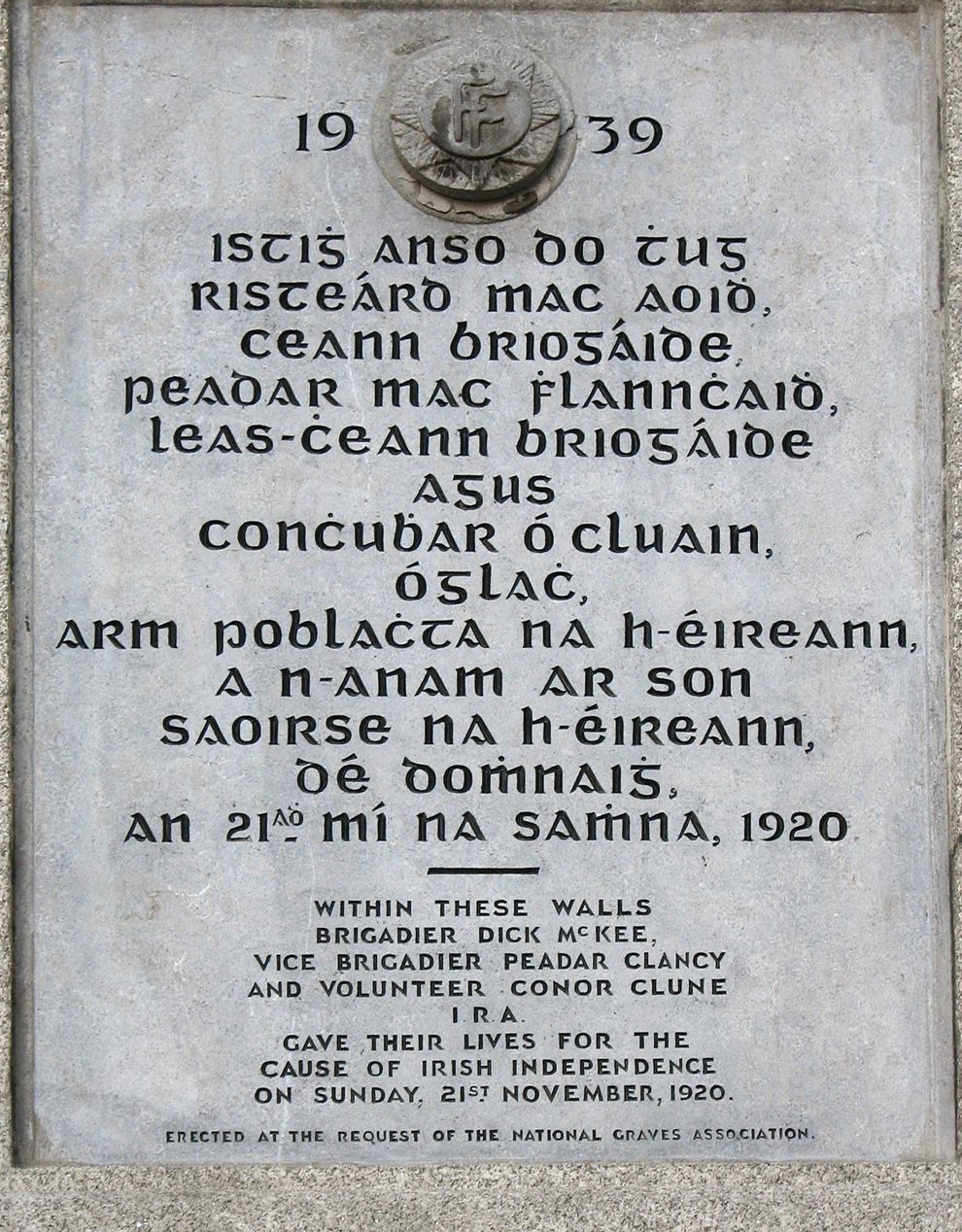

1920 Bloody Sunday in Dublin left 30 dead when the IRA clashed with British troops and Ulster police.

1934 Teenage Ella Fitzgerald sang at an amateur night at the Apollo Theatre. On a dare with girlfriends she had entered as a dancer. But when her number was called, she sang. In some Sy fy movie lost in the mists of my mind, one character swears that someone is an alien. The proof. No reaction to Ella Fitzgerald singing! Proof positive.

1988 Ethel Blondin-Andrew, a First Nations woman, was elected to the Canadian House of Commons, a graduate of the University of Alberta and a school teacher in the Western Arctic in the Northwest Territories. She was the first woman from the First Nations to enter parliament and served ten years.

‘The Cremators’ (1972)

IMDb runtime of far too long at 1 hour and 15 minutes, rated a generous 2.2 out of 10 by 229 slackers.

Genre: Sy Fy and Boredom.

Verdict: So bad that it’s bad.

A flaming orb lands on Earth and after toasting an Indian or two it then hides in a lake for three hundred years. That prelude took fifteen minutes as we watch the same segment of the Indian running down a hill in a five minute loop.

A geologist digs up some opals which stimulate the flaming orb which has been Rip Van Winkle-ing at the bottom of the lake. Yes, the flaming orb was hiding in the bottom of a lake. Cute trick. Awakened, flaming orb toasts various people in the hills.

No one finds this strange because the Surgeon General has said smoking kills. And where there is smoke there was fire. Great logic that.

The geologist and his squeeze investigate since the authorities are too busy practicing their bumpkin accents.

The flaming orb lurks around keeping an … [a what?] on Geologist in between toasting others. Why flaming orb does not toast Geologist and spare viewers more treacle is unknown.

Consulting the NRA play book, victims try shooting the flaming orb. More toast is the result. Finally Geologist figures out something or other and finishes off flaming orb. At last.

What the orb was, what it was doing, and who cares all are questions left unanswered.

It is a Roger Corman production. Hmmm. It is poorly lit so most of the scenes are lost in the murk. The editing destroys continuity. The acting is … well, it is the first and last credit on the IMDb for most participants. The direction is absent.

Director Harry Essex wrote two excellent screen plays: ’The Creature from the Black Lagoon’ and ‘It came from Outer Space.’ Each is discussed elsewhere on this blog. He also wrote this slop. Naughty Harry!

That inflated 2.2 includes several 8’s from raters who rated it so bad it is good. Imbecilic but true.

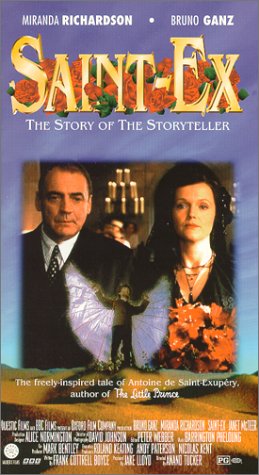

‘Saint Ex’ (1996)

IMDb meta-data is run time of 1 hour and 22 minutes, rated 5.4 by 144 cinematizens.

Genre: Bio-pic and Disappointment

Verdict: Read the books.

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944), just wanted to fly, and fly he did. In 1908 he saw his first airplane and seldom had eyes for anything else after that.

Bruno Ganz plays Saint Ex, as he was called even by his sisters. He had a vexed relationship with Consuelo and that is the focus of this film where she is played by Miranda Richardson as a selfish, manipulative, petulant woman with no interest or activities of her own part from making him miserable. Blame the screen writer.

Ganz and Richardson were enough to capture my interest, plus the prospect of some flying sequences. But alas, the actors have little to do, though they try their best to make the most of it, and the flying sequences. Well, what flying sequences? We had a better flying sequence against a green matte in Amsterdam once making a tourist video. What we see here is clumsy, patently fake, and all too much like a school play.

Moreover the story dwells on ‘The Little Prince’ from go to whoa as his alter ego, though in fact he tossed that off in a few weeks while travelling the United States to raise money for Free France. It was not a lifetime preoccupation as implied here.

By concentrating on ‘Le Petit Prince,’ the story elides and ignores most of his career as a world travelling aviator, international journalist, and published novelist. Occasionally some passages from his elegiac prose are narrated, and that is the best part of the film because it communicates a feeling for the sky, the wind, the earth below, and the eternity of the stars. But alas, there is too little of that.

Try ‘Southern Mail’ (1929), ‘Night Flight’ (1931), ‘Wind, Sand, and Stars’ (1939), and ‘Flight to Arras’ (1942).

This is the last photograph of Saint Ex.

This is the last photograph of Saint Ex.

It has Ganz declare in the last scene that he is a ‘fighter pilot.’ Not so, he flew reconnaissance and the Lockheed P-38 he had was unarmed, despite appearances in this movie, to make it lighter for distance and speed. It was also a notoriously difficult plane to fly even for pilots trained in its peculiarities with youthful reflexes, unlike the forty-four year old St Ex. Did he have a self-destructive streak? Perhaps.

The archival interviews with people who knew him are informative, though at the end when the credits roll the camera work on some of them is demeaning and gratuitous. Really!

There are no linked critics and no user reviews on IMDb. Never before have the opinionators failed to fill a vacuum on the IMDb. However, all was not lost because the entry on Amazon for the DVD is accompanied by some idiotic comments, including one that has Saint Ex dying to prevent Charles De Gaulle from making France socialist. Don’t believe me. Look for yourself. It restored my faith in the endurance and proliferation of human idiocy.

20 November

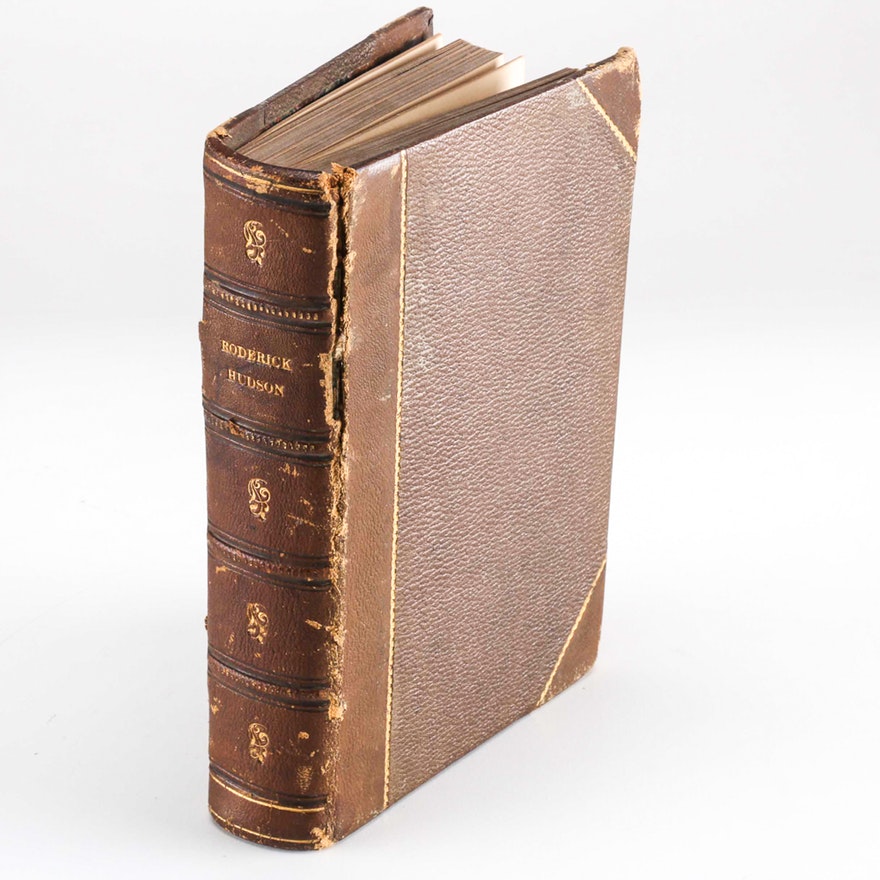

1875 Henry James published ‘Roderick Hudson,’ his first novel. Not read this one, but have read The ‘Ambassadors,’ ‘The American,’ ‘The Bostonians,’ ‘The Princess Casamassima,’ ‘The Turn of the Screw,’ and ‘Washington Square.’ A master of fine detail but ever so orotund. What I remember is the dedication of the hall in ‘The Bostonians,’ the door opening (where there is no door) in ‘The Turn of the Screw,’ and a gentleman who is sitting down (when he should be standing) in ‘The Ambassadors.’

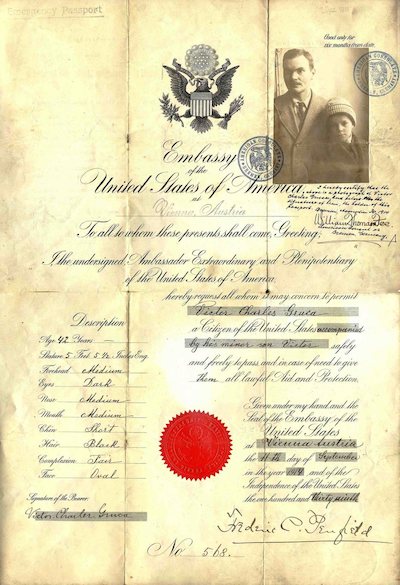

1914 US State Department required photographs on passports as shown below. I look like my picture. Gulp! Somewhere — lost to me now — Georg Hegel recommended pictures to go with travel papers in the 1820s.

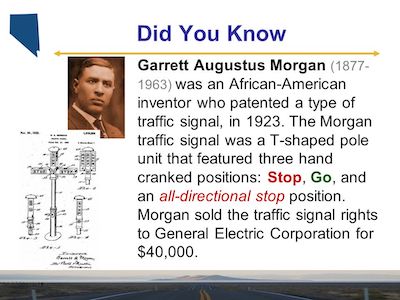

1923 Garrett Morgan patented the three-position traffic signal with buffer between stop and go, making the transition safer. He was the child of two former slaves. This butter evolved into the amber light, which in some jurisdictions follows the red, and in others the green. In both cases it means ‘sped up!’

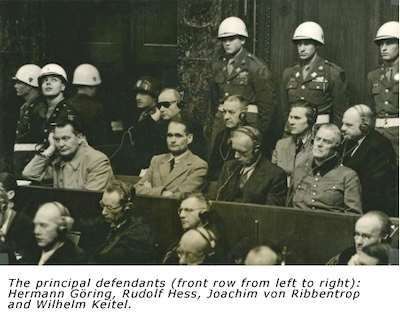

1945 Nuremberg Trials began with 24 individuals.

1985 Windows 1.0 was released two years late, and has continued in that manner. I left the PC world about ten years ago for the Mac World and will not go back.

19 November

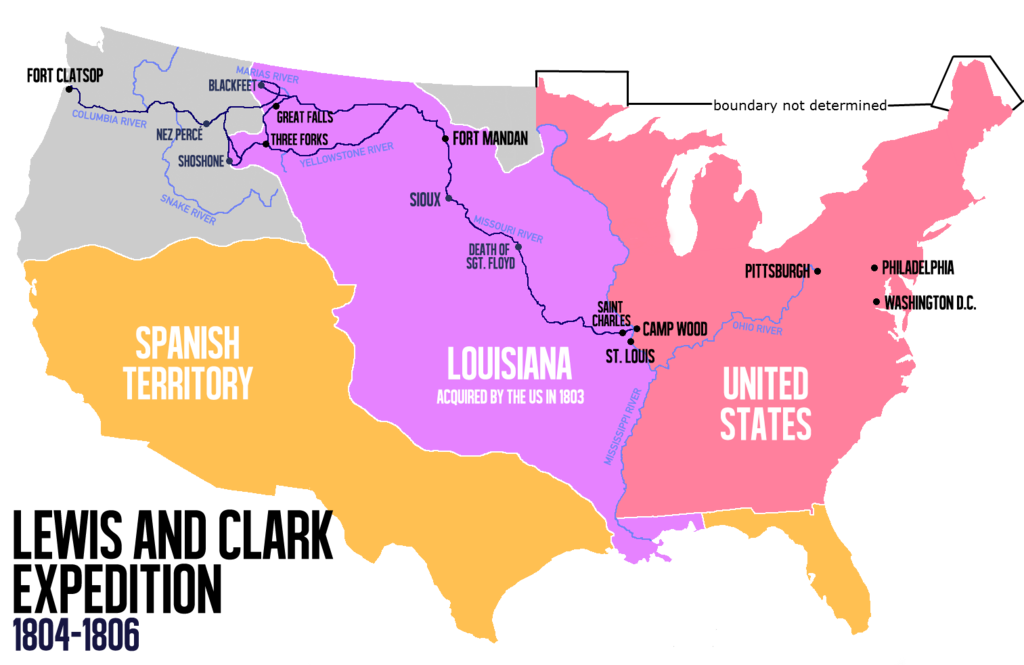

1805 Lewis and Clarke reached the Pacific Ocean, having started in Washington D.C., and using Pittsburgh as the base camp.

1863 Sixteenth President Abraham Lincoln delivered 272 words at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Here’s a fun exercise time-wasters. Imagine how Faux News would bastardise this speech today.

1872 Edmund Barbour of Boston patented the first adding machine capable of printing totals and subtotals. One of his early model is pictured.

1903 Carrie Nation attempted to address the Senate on demon rum from the visitor’s gallery. Earlier she had tried to corner President Theodore Roosevelt in the White House but he was too fast for her. She was 6 feet tall and led numerous hatchetations in which saloons were destroyed from Kentucky, Kansas, to Texas and back.

1926 At the Imperial Conference in London the Balfour Declaration proclaimed Britain and its dominions to have equal constitutional status. In led to the 1931 Statue of Westminster which made it official that the dominions were sovereign.

18 November

When What

1477 William Caxton published the first printed book in England, Earl Rivers’s ‘Sayings of the Philosophers.’ Books, we have read a few.

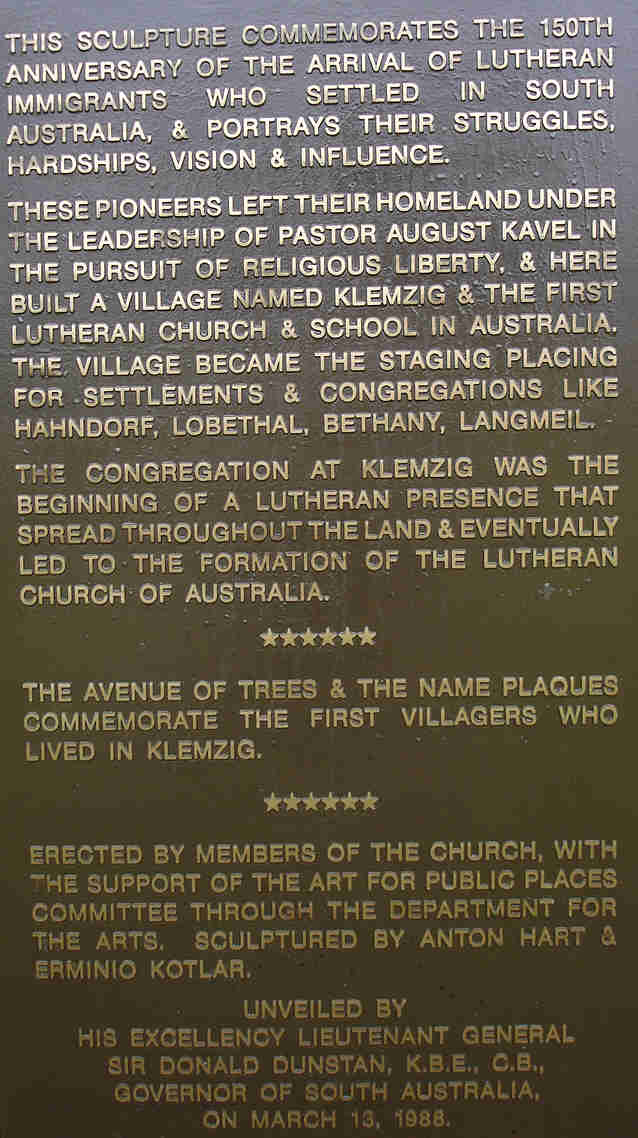

1838 Scottish businessman and chairman of the South Australian Company, George Fife Angas, sponsored twenty-one German Lutherans who arrived in South Australia. More followed in short order. Some settled in Hahndorf which we visited in August 2018.

1865 Mark Twain published his first story, ‘The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.’ Read it in high school.

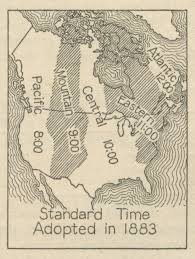

1883 At noon American and Canadian railroads begin using four continental time zones to end the confusion of dealing with thousands of local times. US Congress enacted time zones in 1918. It ended the distinction between town time and railroad time in thousands of places. See Jo Barnett’s ‘Times Pendulum’ (1999) tells some of this story. I found the book unfocussed and did not discuss it on the blog.

1963 Bell Telephone in the US began to market push button telephones to replace rotary dial phones. The charm of the pulse dial was lost, replaced by tone. No doubt Luddites mourned its passing.