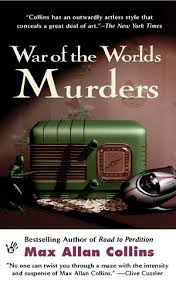

Goodreads meta-data is 256 pages, rated 3.71 by 276 litizens.

Genre: krimi

Verdict: Fun but flabby

When CBS executives pressured Orson Welles to reduce the verisimilitude of the script for the Halloween broadcast in 1938, his standard defence was that no one would be stupid enough to think it real. Ah, he should have paid more attention to P. T. Barnum. There is always someone that stupid with many friends, just look at the White House today.

In 1938 Welles was an infant terrible of twenty-three years already with a string of theatrical triumphs behind him. While he was a creative genius, as well he knew, he needed help and founded the Mercury Theatre with John Houseman to produce his genius. Yes, that John Houseman.

Welles never did one thing at a time; while he continued to stage dramas for the Mercury Theatre on Broadway, he also branched out with the Mercury Theatre of the Air, while simultaneously writing scripts for movies. If he had fewer than three separate and independent projects to work on in a day, he became bored.

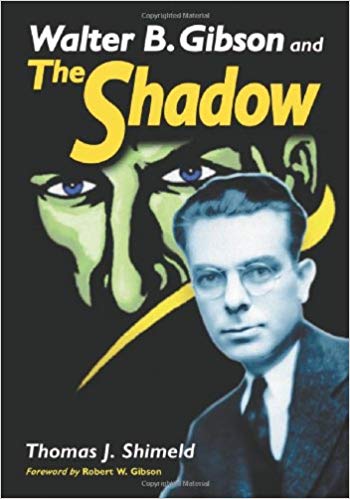

Welles own career in radio started with that voice as the caped avenger in ‘The Shadow,’ who knew what evil lurked in the hearts of men, rivalling Santa Claus in contravening of the NSW Privacy Laws. To return to this yarn Welles is hatching a new project and he brings into the tent the writer of ‘The Shadow’ stories from earlier years, Walter Gibson, who is the narrator thereafter.

Gibson is no ingénue but even he is swept up in the profligate and prodigious energy that Welles exudes, and — since all expenses are paid — he goes along for the ride. He enters just as the Mercury Theatre of the Air is rehearsing for The War of the Worlds. It is fascinating to read of the organised chaos that produced live-to-air radio in 1938. While on air and in role before the microphone Welles scribbles new lines for the other players to whom he hands them.

Genius he may be, but that most levelheaded of men, Houseman, knows Welles is riding for fall, and he tries to reign Welles in, again and again. Ditto the CBS executive who delivers the budget, but who also wants to curb the enthusiasms of the Wunderkind least the corporate goodwill evaporate taking the money with it. Gibson observes all of this with wry detachment.

The Welles that emerges in these pages conforms to the general impression. Genius, yes, without a doubt, charming and charismatic to get his way. But also he can be crude, rude, and arrogant by turns. And ever theatrical in appearance, tone, and movement. He could turn the taps on for love or hate with equal ease and switch between them in a breath, because he did not mean any of it. Not so much that he was insincere, as like an Olympian god, he was indifferent to the matters of mere mortals. (What a comeuppance then to spend all those later years pitching for Findus frozen peas and Paul Masson wine in television advertisements. These make painful viewing on You Tube. How low the Olympian fell before the long arc of justice.)

Every time Houseman forced a compromise on him after much resistance and rancour, Welles would give in with lavish good grace, and promptly undermine the agreement. To give an example, if CBS insisted that no real names be used. He made up names that in the script did not look like real names but when said with certain inflections — which he coached the actors to do — sounded like real names of people or places. When CBS said the script cannot have a simulated President Roosevelt speaking, after hours of angry resistance, Welles conceded by substituting a Secretary of the Interior. He then cast as the Secretary an actor famous for his perfect impersonation of FDR. And so on.

So Houseman decided to teach Welles a lesson he would not forget – SPOILER ALERT — by framing him for murder! As an accomplished producer Houseman knows everything about staging and with the help of a woman scorned he fakes a murder scene with Welles’s name written all over it – literally, for Welles to find a few hours before the ‘The War of the Worlds Broadcast.’ That’ll tame him was Houseman’s hope. A subdued Welles could then be guided to moderate the realism of the upcoming broadcast, thought Houseman.

Yes the frame-up did stun Welles, but the show must go on and, if anything, the spectre of the murder fired him to make even greater effort in the broadcast. Houseman had underestimated his man.

I said ‘flabby’ above because I found the pages padded with endless and pointless descriptions of clothes, decor, food, and the appearance of players who walk across the page. Buried in this verbiage is short story that is a corker, notwithstanding the fact there is almost no investigation, no psychological depth, just an elaborate prank within an even more elaborate prank. But the evocation of radio drama was fascinating and I intend to listen to a few from Audible, starting with ‘The Shadow!’ On a similar note I read years ago, and have dredged up the reference thanks to the app Book Collector, John Dunning, Two O’Clock Eastern Wartime (2001). It too evokes the magic of radio in 1942.

A number of other items related to Welles’s ‘The War of the Worlds’ broadcast have been discussed on the blog, including Ed Murrow’s documentary on it and Hadley Cantril’s study The Invasion from Mars (1940). Seek and ye may find.

It turns out there were plenty of people dumb enough to believe that invasion story, despite the station breaks, the newspaper advertisements, the fabricated place names, the incorrect terminology, the elapsed time, and any number of radio-addicted children who recognised the voices of the actors. These people vote, drive cars, and have opinions. Think of that. Look around, they are your neighbours today.

Collins is a writing industry from his Iowa home with a number of series. This one is in a set of so-called Disaster novels, that centre on a real, or in this case imagined, disaster, e.g., the Hindenburg crash, the attack on Pearl Harbor, the London Blitz, or the assassination of Huey Long. In them he mixes real people of the time and place with some fictional ones to stir the pot. He does a great deal of research for the context, but anachronisms still appear, as he admitted in the afterword to this novel. These always jar.

Genre: Krimi

Genre: Krimi Barry Maitland

Barry Maitland h it and another five seemingly respectable Victorians are murdered and each, it turns out, was a despicable villain beneath the veneer of respectablility. With each of the eight victims is an inscrutable symbol [see front cover below].

h it and another five seemingly respectable Victorians are murdered and each, it turns out, was a despicable villain beneath the veneer of respectablility. With each of the eight victims is an inscrutable symbol [see front cover below].