The Salamander is an arsonist in Occupied Lyons in 1943. A fire in a cinema immolated nearly two hundred patrons on a freezing winter’s night.

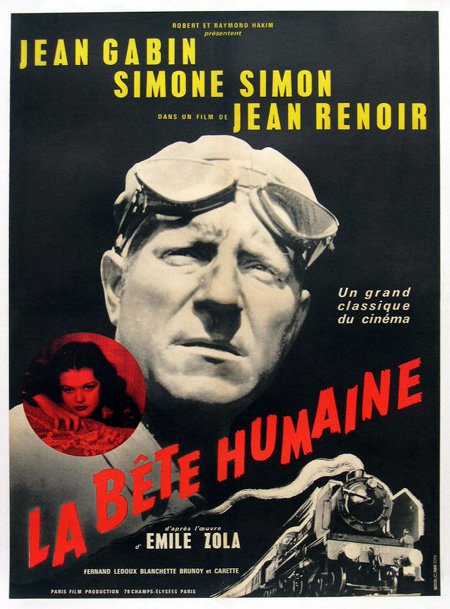

Screening was ‘La Bête Humaine’ (1938) from the novel by Émile Zola and realised by Jean Renoir. Many of the victims of the fire were railway workers and their families.

The central characters in the celluloid story were railway workers led by the peerless Jean Gabin before his face was scarred by German shrapnel in 1943 in North Africa. Many rail lines converge on Lyons, giving it a large resident population of the chemin de fer.

The freezing weather, absence of materials and expertise, and infighting among the responsibles in the civic administration combine to preclude any forensic investigation. There is a very great deal of duck and cover. Then by chance a German fire chief just happens to show up and throws his weight around, seemingly determined in all but word to misdirect and confuse. Yet he must be there for a reason.

The Nazi commandant is one Klaus Barbie, young, educated, debonair, sophisticated, handsome, bilingual, and blood thirsty, a soft-spoken vampire.

Called the Butcher of Lyons for good reason.

Called the Butcher of Lyons for good reason.

Was the fire an act of the Résistance that somehow went wrong, or internecine conflict among factions of the Résistance? Either is possible. Was it Klaus Barbie’s way of attacking the Résistance? This is certainly within the bounds of possibility. And if he did, he might prefer not to publicise it, just to trade on the doubt. Or is a murderous arsonist at large threatening one and all?

A large gathering of hundreds of nasty Nazis is scheduled for Lyons very soon, and to allow for the histrionics of their conclave it will be convened in a huge, old opera house full of dry timber, a catacomb of rooms, with a maze of gantries and catwalks that have never been mapped, side entrances, underground loading docks, concealed exits for divas to elude adoring fans, and other mysteries. In short, an arsonist’s delight and a nightmare to police.

Barbie will not delay the meeting of the coven. To do so would damage his prestige and be an admission that he cannot control Lyons. Uh huh. Is that because the first fire was his and he feels safe, or is it just arrogance? Not even his superiors in Paris are sure and so they send St Cyr and Kohler in case there is a firebug at work. Of course, if a Nazi barbecue occurred the retaliation is unthinkable and that knowledge motivates St Cyr and Kohler to superhuman efforts, and writer Janes spares them nothing.

Kohler is a good German but not a good Nazi. St Cyr is a good cop and patriot, but crime is crime.

There are the usual plot twists. In this outing St Cyr seems unstable, accusing nearly everyone he mets of the crimes. Kohler, for once, has cut back on benzedrine and is calm by comparison, though he is caught with pants down and survives.

There is a great deal of description that goes beyond setting the scene. This is an early entry in the series and the writing is uneven. But the portrayal of Barbie is ambitious and measured. Mad and bad, yes, but controlled and calculating, too, and well aware of the fact that his own superiors could cut his throat at anytime for reasons of their own. As always the stifling and exhausting atmosphere of the Occupation is the principal character.

But the greatest fault is the presentation on the Kindle. The text is continuous even when it cuts back and for the between Kohler and St Cyr. Kohler is in one part of the city creeping through cellars looking for phosphorous and St Cyr is at a hotel checking on guests and luggage. When the scene changes from one paragraph to another there is no signpost of any kind, no blank line, no asterisk, no signal in the text. Ergo I was taxed to re-read many paragraphs when I realised it had switched from one to another. The publisher bears responsibility for this needless levy on my time and patience. Tsk, tsk, and tsk.

When reading Marc Bloch’s memoir ‘Strange Defeat’ (1940) for the first time years ago, I had a conversation with a very intelligent philosopher who found my curiosity about Occupied France odd. His line was that the defeat in 1940 was the cleansing failure of a corrupt capitalist regime. And after all, as Bloch notes, life went on the day after pretty much as always, hence Bloch’s title. I did protest to this intellect that changes came, but these, I was told, I had got our of proportion. Ah but I continued to protest, Bloch himself joined the Résistance and was captured, tortured, and killed by the Nazis. This fact was a mere bagatelle to my interlocutor. Bloch brought it on himself that was his line. Really nothing had changed from one day to the next with the change of the flag. That philosopher ascended to the professorship confident in his judgement. All very like those academic apologists for Pol Pot, Mao, and all the other mass murders.

St Cyr and Kohler know what this great intellect did not, does not, know, reality comes through the skin.

Skip to content