The overweight, crotchety, curry gobbling, beer swilling, stained necktie wearing, disheveled, immaculate tennis shoe wearing Sikh inspector of police is on the job again. Hooray! This is the seventh title in the series.

Singh is a Singaporean, though many there deny it, most of all his superiors in the police force, who repeatedly send him on foreign assignments, like the one in this story, to get him our of mind and sight. He is indeed an ambulatory eyesore, a fact that he is quite comfortable with.

Singh goes to London on an exchange program where he is assigned to review community policing! Those who know Singh, know what he thinks of that. Sitting at a desk reviewing case files is not what he does.

The sojourn is made all the more difficult because Mrs. Singh, she of the curries, has come along, too, over his prostrate body for he tripped over her suitcases. Her unnumbered family has many colonies in London which she plans to visit bearing gifts.

While he finds plenty of good curry in London, and that is crucial, he also finds….. While the formal assignment is a report no one will read, he soon becomes aware of a hidden agenda. Someone wants an investigation of one cold case, and preferably done by someone who is not as rule-bound as the Bobbies have to be for fear of offending anyone in a community. For that kind of job Singh is just the man!

In between enormous curry meals that leave him nearly comatose, Singh barges around asking the questions the ever so polite Bobbies dare not ask, least they give offence to some member of the community. It is quickly apparent that many lies have been told and that further piques his interest.

Shamini Flint

Shamini Flint

The mix of the serious and the comic in these krimis is disconcerting to this reader. Much of this krimi is pretty grim. Not to my taste. But much is jocular and light.

Author: Michael W Jackson

The 100 Greatest novels?

We spent several hours, day and night, discussing Robert McCrum’s list of ‘The 100 best novels written in English’ from the ‘Guardian.’

Google will produce several associated lists but the one I mean is found at

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/17/the-100-best-novels-written-in-english-the-full-list

The list is the product of two years of ‘careful consideration.’ The introduction refers to the list as the ‘greatest’ novels.

The work must be a novel and written in English. When we went through the list we also supposed there was an additional element, every author only has one novel listed. They are listed in chronological order.

Yes, one can quibble over the definition of a novel, or even perhaps written in English (see the impenetrables below); entertaining perhaps, but hardly productive. And then there is that word ‘great’ constrained by the number one hundred. What does make a novel great? On there a few words at the end.

We read the list and discussed what we knew about each writer, or took note of writers that were unknown to us, consulting Professor Wikipedia at times for more information.

The list begins with ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ (1678) – a ‘story of a man in search of truth told with clarity and beauty,’ says McCrum. Much as we like Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’ (1386), a novel they are not.

Robinson Crusoe, Lemuel Gulliver, Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, Clarissa, Emma, and Dr Frankenstein get their dues.

The first krimi is Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Moonstone’ (1868). Though Edgar Allan Poe is there with his one spooky novel, along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler follow, but not the uncrowned king of noir, Ross Macdonald. Tsk. Tsk.

We loved the description of George Elliot’s ‘Middlemarch’ (1872) as ‘a cathedral of words.’

Benjamin Disraeli is there, before he became British prime minister, but also Jerome K. Jerome. Who?

There were others that struck no bell with me:

George Gissing, ‘New Grub Street’ (1891)

Fredrick Rolfe,’ Hadrian the Seventh’ (1904)

Max Beerbohm, ‘Zuleika Dobson’ (1911)

Sylvia Warner, ‘Lolly Willowes’ (1926)

Henry Green, ‘Party Going’ (1939)

Elizabeth Bowen, ‘The Heat of the Day’ (1948)

Elizabeth Taylor, ‘Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont’ (1971)

Marilynne Robinson, ‘Housekeeping’ (1981)

Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘The Beginning of Spring’ (1988)

Joseph Conrad’s ‘The Heart of Darkness’ (1899) made the cut. But is it a novel or a long short story? Quibble. Quibble. The trouble with quibbles.

Also on the list is the impenetrable prose of Theodore Dreiser of whom is it is said ‘he was no stylist.’ Indeed. Speaking of the impenetrable, there is Ford Maddox Ford, ‘The Good Soldier’ (1915) and James Joyce, ‘Ulysses’ (1922).

While there were many famous titles, I was not sure all were great novels. There was John Buchan’s ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ (1915) which is a rattling good story, but is it a great novel? It may be the cornerstone of the espionage genre that followed, but is that enough to merit inclusion when Agatha Christie is omitted?

It will take a lot more than assertion to convince me that Ernest Hemingway wrote a great novel. The title is ‘The Sun Also Rises’ (1926). Oh hum. I also wondered about John Dos Pasos, ‘Nineteen-Nineteen’ (1932) and ‘At Swim-Two-Birds’ (1939) by Flan O’Connor and — most of all — H. G. Wells with ‘The History of Mr Polly’ (1910). For Wells I might have swallowed one of science fiction titles like ‘The Time Machine,’ ‘The Invisible Man,’ or ‘The War of the Worlds’ but not this trite and self-indulgent disguised autobiography.

While the demigod William Faulkner is there, the novel cited is not his most astounding. ‘As I Lay Dying’ is the one, but his most hypnotic novel is ‘Absalom! Absalom!’ (1936). The novel he thought was his best was ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1929). By ‘best’ Faulkner meant the most painfully true.

One book authors are here like Harper Lee.

Carson McCullers who is in another, higher league than Harper Lee is not, nor is William Styron.

Two towering English writers are also conspicuous by their absence: Barbara Pym, ‘Excellent Women’ (1952) and Antony Powell, ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’ (1951-1975). Also absent is John Galsworthy, ‘The Forsyth Saga.’

The list ends with a number of contemporary writers, most of whom leave me cold, e,g., Martin Amis, John McGarhan, Don DeLillo, and Peter Carey. More oh hum from me.

In addition to the expatriate Peter Carey, Australia is represented on the list by the egregious Patrick White. Absent is the luminous David Malouf; when will the Nobel Committee wise up?

David Malouf

David Malouf

There is a Canadian writer, or two, but not the profound Gabrielle Roy, a bank clerk by day and a communicate with eternity by night. To this day she is listed on the Amazon Canada web site as Roy Gabrielle, despite many corrections offered by we readers!

Whoops, Roy did not write in English.

Nor does Willa Cather make the list, and the list is poorer for it.

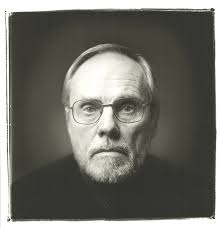

Robert McCrum

Robert McCrum

Coda

The pleasure of an exercise like this is that it makes one stop and think, first about the old friends on the list, also about the titles and authors one knows of but has not read. It also introduces new authors and other titles for the reader. Each is welcome.

But most of all it makes one think about the criterion: great.

Is a great novel one that influences other writers?

One that wins readers across generations and cultures?

Is it one that creates an enduring world with its words?

Is it one that leaves an indelible impression of the mind of a reader?

A great novel is one that does such things because there are many, even several, ways to be great.

‘Conclave’ by Robert Harris (2016)

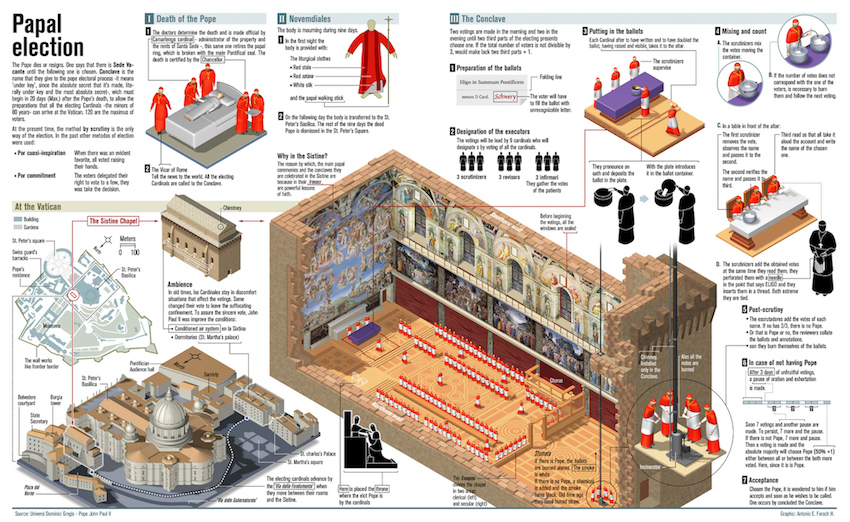

What is the oldest continuing electoral system in the world? It might be the conclave that elects the Bishop of Rome, known to the world as the Pope. For a thousand years a closed meeting of eligible voters has chosen the next Pope.

When the conclave has started the last few times, I have wondered how it works behind those closed doors. When I have brought up this question – how does it work – with colleagues and friends none have taken any interest in the subject, neither the psephologist nor the theologians of my acquaintance. I left it at that on those occasions.

When I saw this title, I picked it up in the hope it would shed some light on some of the mysteries. It does!

Behind the closed doors there is a very specific procedure which has ancient and holy origins. Pedigreed it is, but it was only codified and published in 1996 by Pope John Paul II in the Apostolic Constitution. (See Wikipedia.) An earlier initiative in 1970 limited voting to cardinals under the age of 71.

In sum, there is a manager of the process from the Curia who looks after all the details of travel, housing, security, and so on, and chairs the voting sessions. There are two sessions each day. There are no preliminaries beyond the social niceties as the cardinals gather in Vatican City on the day before the Conclave begins. The next day they convene behind locked doors and vote. There is no talking, just praying, meditating, and voting.

The ballot is secret and they vote by writing the last name of the cardinal they support on a piece of paper and drop it in a receptacle. They do this one-at-a-time so the process is slow. A printed list of call cardinals is on each desk. They do not talk in the Conclave.

The votes are counted by three cardinals, previously designated by the manager, who in this case blindly drew names from a box. Selection is done publicly before the assembled cardinals. To count, each ballot is extracted one at a time, and the name on it read aloud. For 118 votes all of this takes time.

But wait there is more! When this count is done a second group of another three cardinals, also chosen earlier at random, recounts the votes, this time silently. When it confirms the results, the manager announces the distribution of the votes.

This practice stems from the mistrust and brutality of Papal election in bygone days. Think of that Borgia pope whom Jeremy Irons played as a clown.

To gain the crown a candidate must have a super-majority of two-thirds of the total vote. If no one reaches that figure, there is a break for lunch and another session in the afternoon. The proceedings are punctuated by pauses for prayer and meditation before and after each vote.

If someone secures the two-thirds majority, the deed is done. However, if after eight votes, no one reaches the super-majority, then in the ninth and any subsequent ballots the bar is lowered to a majority of fifty percent plus one of the votes cast.

As in any election, the greater the majority, the greater the moral authority of the electee.

The book is replete with such details and I found all of that very interesting. I will return to these formalities later, but there are also informalities to consider.

No one declares candidacy, but there are candidates aplenty in this story. There are many Italian cardinals and there are recognised leaders among them, more than one.

Leadership can take several forms, as an advocate of certain theological position, as an office bearer in the Curia, as an organiser of good works, as ….. Of the two leading Italians in this story one is an advocate of a return to old time religion of the Latin mass, the denunciation of Islam, etc and the other an intellectual who has long been Secretary of State for the Vatican City and is known far and wide as thoughtful, rational, cooperative, constructive, and one who can get things done.

In addition, the third world cardinals coalesce from the first dinner around an outstanding exemplar, though it not so clear to this reader why they he is so esteemed, apart from his titanium self-confidence.

The Curia always has an implicit candidate and in this account he is a Canadian, who, as the story unfolds, has been for years distributing Papal monies in a strategic way. (Guess!)

At the first dinner on the arrival date, these leaders sit at distant tables surrounded by their supporters. Any high school class president would recognise the pattern.

None is without sin, and each falls along the path of the voting. There is much drama, and the outside world intrudes.

The details about the voting left a few questions for me. Cardinals over seventy attended in this story but evidently they did not vote. What then did they do? Nap through the Conclave? They came all the way to Rome to nap, well, to show solidarity, but still it seems strange to command that they travel to Rome and yet once there to regard them as too infirm to vote with intelligence and good faith.

Moreover, it was not clear to me if the two-thirds requirement was based on eligible voters (those seventy and under) or all in attendance, one hundred and eighteen in this story, or the vote cast, though no one seems to have abstained in this story. Maybe I missed the explanation.

I was also surprised to learn that cardinals have different titles, Cardinal-Bishop, Cardinal-Priest, etc.

My reading left some gaps in the plot. I never did figure out who identified and sent for the Nigerian woman who was the downfall of one candidate. Nor was I sure why his one sin thirty years ago disqualified him.

Spoiler alert!

The winning candidate is the least likely, and this reader saw that coming from the first page when he was introduced. (Why else was he there?) How he came to the forefront is put down to the Holy Spirit. That may have satisfied some, but not all readers I should think. It is just too easy, I am afraid and my suspension of disbelief snapped there.

Both Wikipedia and Amazon’s mechanical turk indicate several other books about Papal elections and if ever I am motivated to return to the subject there is bibliography. Indeed, Harris offers some titles at the end of the book.

All is made clear. (Irony.)

All is made clear. (Irony.)

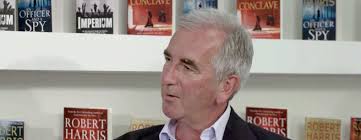

Robert Harris is a superb writer and he brings to life an interesting array of characters, endowing many with an interior life that is rich, complicated, humane, and realistic.

Robert Harris

Robert Harris

He treated the spiritual dimension with great skill. The sincerity of the believers is given full measure and the story is richer for it. There is sin, but there are no villains.

His three volume novel about Cicero is only thing I have read, and I have read a lot about Cicero, that made sense of Cicero’s contradictions. Sometimes fiction is the best way to make sense of facts.

‘City of Fortune: How Venice won and lost a naval empire’ (2011) by Roger Crowley

Now and again I have had the urge to go to Venice, but never have. To scratch that itch I decided to read a history of the damp republic.

A fishing village on the lagoon is first mentioned in extant chronicles at about 800 A.D. Venice was not a Roman settlement, unlike nearly every other city in Italy today. The mud flats in the lagoon were home to fisher folk who were left alone by others because there was nothing there worth having or worth stealing.

From this embryo grew a mighty city that dominated much of its world for three centuries.

The constant threat of the sea, aqua alta, meant everyone in Venice had to cooperate against nature. That common and constant threat produced a tight social order that put an absolute premium on planning, discipline, and initiative, and most important of all on social cooperation both horizontal and vertical. The commune took precedence over the individual and orders were obeyed.

This is my reading of it because the book is mainly focused on the wars of conquest and decline that led to the empire and then its collapse.

While most European cities between 1200 and 1500 developed an increasingly elaborate hierarchy based on blood, money, and religion, by contrast Venice remained largely undifferentiated with a very flat social hierarchy. That proved a bedrock beneath the water. In this way it seems to me that Venice is comparable to that other muddy republic that lived off trade and battled the sea, Amsterdam. See Geert Mak, ‘Amsterdam’ (2001).

The people of the lagoon had almost no terra firma. That was a benefit since it meant no passing war lord wanted to wade out into the mud to conquer it. It was also a weakness since it meant Venice had to live off trade because there was no vegetable patch. It had to be the broker to live.

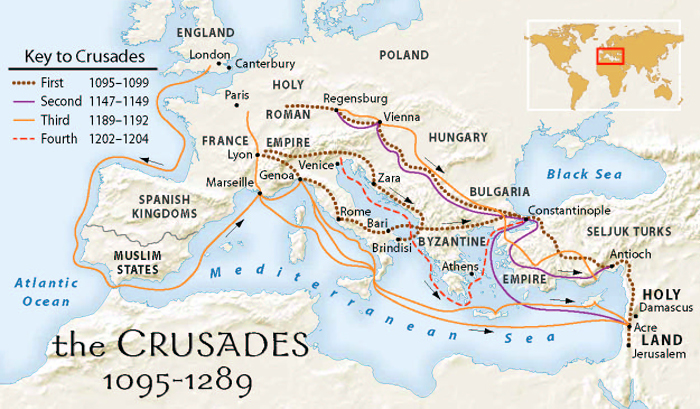

Its conversion from a diet of fish to one of gold began with the Fourth Crusade in 1200 which occupies the first one hundred pages of this book. It is a story for the ages.

The crusades were religious, the aim being to wrest the Holy Land from the infidel, and all those who participated in the effort would be blessed in the Christian heaven for eternity. Sounds like a Holy war because it was.

The first three crusades had limited successes and unlimited failures. They left behind Christian enclaves in the Middle East. Of course, the largest Christian community in the Middle East, as we call it today, were the Greek orthodox Christians in Constantinople. The author refers to that city of the Bosphorus by that name, though at the time it called itself New Rome.

The endless religious schisms in the preceding millennium had divided the Christian world into these poles: the Universal Church in Rome and the Greek Orthodox Church in New Rome. The twain did not meet. At each pole there were further divisions: Two fingers versus three fingers, is one example. (Either one gets it or one does not.)

The Byzantine Empire in New Rome had participated in the earlier crusades, but not as fervently as Popes in Rome thought it should have done. This was another source of friction in the Christian world.

When Saracen leaders in Syria began to squeeze the pimples of the Christian enclaves in Lebanon, the Roman Pope called for a Fourth Crusade to rescue them and to conquer the Holy Land once and for all.

Whereas the earlier crusades had been more or less spontaneous movements of mobs of Christians from Europe to the Holy Land by any and all means, motivated as much by the selfish desire to save their individual souls as to cleanse the Holy Land of Islam in a rag-tag mob of inexperienced, impoverished, undisciplined and diseased hordes who were often unarmed, this crusade was different. The Pope made an effort to organise the Fourth Crusade. by commissioning a number of nobles to lead and manage it.

The plan called for thirty thousand crusaders to be raised, equipped, provisioned, supplied, organised, and assembled in Venice, from whence Venetian ships would transport them to Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and other ports along the coast of the Middle East. This crusader army would be commanded by Christian lords, barons, and knights from the lands of France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, by and large, though others joined the cause.

An advance party went to Venice to prepare the way. There its members discovered that the Venetians expected to be paid in coin for shipping these souls to the desert. Long and difficult negotiations followed. While Venice had dabbled in sea trade for its living, this project was a hundred times larger than anything previously undertaken. To transport thirty thousand men in a single fleet, along with their arms, equipment, and food, was such a difference in degree from previous trade expedition as to be a difference in kind. Furthermore, a knight must have his steed, and some five thousand horses with grooms, squires, tack, fodder, and more had to be shipped at the same time. Hundreds of ships would be required and thousands of crewmen not he oars and sails.

The Crusaders agreed, reluctantly, to pay 100,000 silver marks, a vast sum equivalent to billions today. The details were many and each was a line-item in the contract, a copy of which remains in the Venetian state archives. Then the Venetians took a year to build the ships, and — once built — agreed on a twelve-month shipping contract to start on a certain day when the crusader army was to embark.

The Venetian Doge, chair of the city council, we might say, though an elderly man over ninety at the time, was keen on the project, and eventually sold it, with all its considerable risks, to the council and in turn to the citizenry. It meant that for a year in Venice all other activities ceased and every citizen of Venice worked on the crusader ships and all that they needed. This focus was enforced by the commune. All of this before a single silver mark had been paid.

The Arsenal became a scene of frenetic activity as ships were produced, logs were imported from Russia along with sail cloth from the England and rope from Estonia. Resources were sucked in and had to be paid for as the work went on and on.

Murphy’s Law applied. Only about a third of the projected number of crusaders arrived in Venice at the appointed day when the meter on the shipping contract started ticking.

The Venetians wanted to be paid, having outlaid nearly all of the treasury to built the crusader fleet and contract the crews, but the crusaders wanted to renegotiate the contract. When the crusaders arrived Venice was more or less broke. But the crusaders did not want to pay for thirty thousand when only twelve thousand had arrived.

Months went by and more crusaders straggled in while others gave up and left. The crusaders camped on mud flats in the lagoon where disease found them. Food was in short supply for everyone. Sanitation is best left in silence.

In the end the Venetians agreed to become participants in a joint venture rather than merely contractors for shipping, this being the only hope of securing a financial return on the massive investment the city had made in the project. They sailed.

It was not plain sailing and they diverted to Byzantium in the New Rome of Constantinople. While the Byzantines welcomed assistance against their Islamic neighbours, they were not keen on an army of thousands of ill-disciplined and increasingly desperate men camped on the foreshore, and still less interested in joining in the crusade. They had had an uneasy but durable modus vivendi with their Islamic neighbours for some time.

Many recriminations followed. Though the Pope had strictly forbade conflict among the Christians on the pain of excommunication, ultimately the Christian Fourth Crusaders attacked and sacked Christian Constantinople. The justification of this Christian on Christian war was as convoluted and tortured as that of a political candidate.

The Fourth Crusade crippled the Byzantine Empire, though it limped on for three more centuries.

Out of the pillage of Constantinople the Venetians got their 100,000 silver marks and another 150,000 for their trouble. While the other pillagers took the money and ran, the Venetians dutifully took the dosh home to Venice, along with much else from Constantinople to enrich Venice. Many of the treasures seen in Venice today, including the four lions on St Mark’s Square, were stolen from Christian Constantinople.

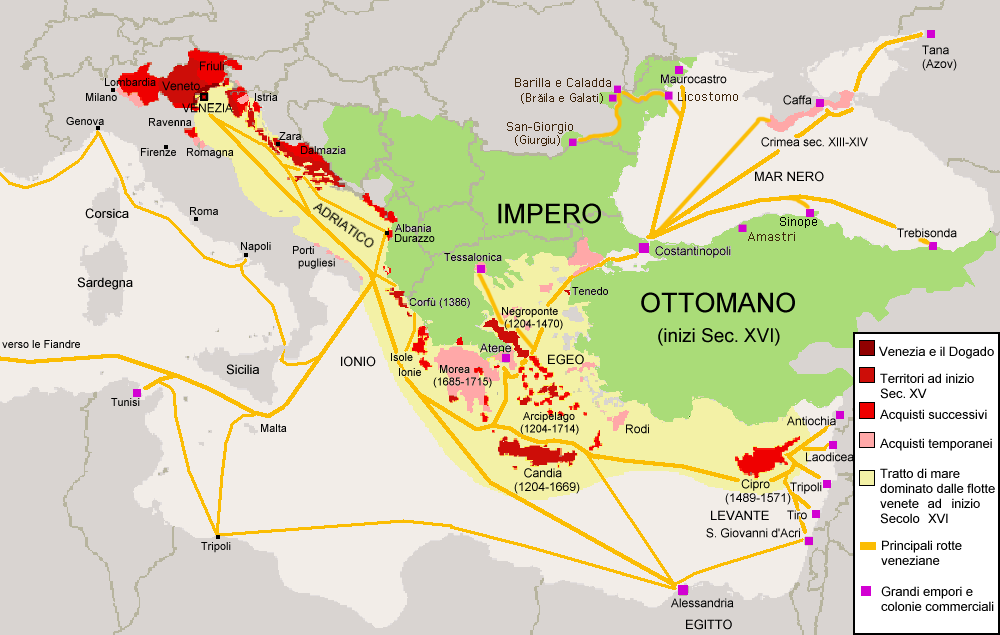

Venice was now the Lion of St Mark, and ruled the waves of the Eastern Mediterranean for the next three hundred years. It had bloody trade wars with rivals, mainly Genoa for a century, but it prevailed partly because of its social cohesion. It established itself on the shores of the Adriatic, Aegean, Azoz, Black, Cretan, Ionian, Levantine, and Marmara Seas.

They established and controlled sea ports, harbours, straits, estuaries, and anchorages, but they did not conquer territory or enslave populations, except on Crete. This empire was a string of settlements along shores under the flag of St Mark dotted along the Adriatic Sea into the Mediterranean Sea and eastward and north into the Black Sea. They never ventured Westward and apart from Venice itself had no settlements on the Italian coast. Nor did they risk the Red Sea to the south.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

Venetian citizenship was closed. Venetians were forbidden to marry outside the civic list. Those Venetians who staffed, managed, and ran the empire’s outposts were strictly regulated, as two chapters of the book detail, but the real regulation was social and not legal.

Even while the Christian and Islamic worlds were at war, the Venetians happily traded with both, to the point of ferrying an Ottoman army from Asia to Europe to attack Christian peoples. In so doing the Venetians made a tremendous profit and an enduring reputation for mercenary mercantilism. Shakespeare is downwind of that.

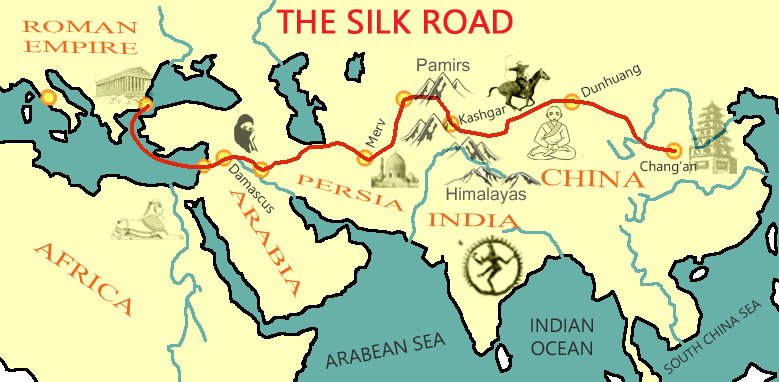

The Silk Road brought exotic luxury goods from the Far East to the Lebanese coast and later to the Black Sea coast, and it is from these goods that Venice made astronomical profits in the high-end market.

Eventually, the Ottomans began to conquer Venetian territories on the Black Sea coast, on the coasts of the Middle East, in Greece, on Crete, in Albania…. Then Venice proclaimed itself the shield of the Christian world and called for a fifth crusade to protect it. Too little, too late.

Used and abused for generations by Venice, other Christians enjoyed the spectacle of Venice supping on its just desserts. In the end Venice bought off the Ottoman but in so doing ceded most of its empire and by 1511 was just another minor city-state as the nation-states of France and Spain became European superpowers. While on a map it retained some marine territories, this was by Ottoman indulgence.

The social cohesion of Venice had disintegrated. In this telling there is no way to know which came first, the social erosion or the defeat. Which precipitated which? There is no doubt that the social discipline failed against the relentless Ottoman abrasions. Individuals enriched themselves first and secreted the money away, sometimes in other cities, like Amsterdam. Other refused to serve the commune and immigrated. While there had always been a few such deviant cases in the past, but in the Fifteenth Century they became the norm.

What finally killed Venice was not Ottoman cannons though they wounded it. Technological innovation delivered the coup de grace. When the Portuguese navigator Vasco di Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to open a direct route to India, Venice’s role as an entrepôt for the Far East, e.g., spices and silk, died within a few years.

Much of the book is devoted to the many Venetian wars with Genoa and the Ottomans and the details of who killed whom in the most creative and diabolical ways. If I want blood-and-gore I can watch the television news where man’s inhumanity to man is on show every night as journalists try to shock without informing us.

The book is well written and impressively researched but did not have the insights into the social, political, ethical, religious, and financial organisation of Venice that I had sought. Many other city-states traded but somehow Venice surpassed them. How it managed, that is what makes me curious.

Roger Crowley

Roger Crowley

Still the book lives up to its title and I can have no complaint.

A few years ago I read Garry Wills’s ‘Venice, Lion City: The Religion of Empire’ (2001). It, too, left me unsatisfied. Wills has shag carpet prose, luxurious to feel, but the book is a litany of one description of an astounding work of art, much of it devotional, after another with little or nothing about their origins and social context. This was a disappointment from an author for whom I had the highest expectations.

My prime source on Venice remains the krimis of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin.

‘The Seven Symphonies: A Finnish Murder Mystery’ (2005) by Simon Boswell

A police procedural set in contemporary Helsinki, where we spent a week in 2016.

The violin proves to be a dangerous instrument when three young women carrying violins are murdered one after another, the first found at the Sibelius monument. Been there.

The police investigation seems to involve only three officers, and they issue no public warning about those nasty violins.

There are many red herrings, some very satisfying.

There is also quite a lot about music, particularly Jean Sibelius’s music. While it is rather technical, it is informative.

The author tries hard to relate the music to the plot but it does not work for me.

While much of the policing is interesting and engaging, I did find the principal officer, Miranda, very immature. Her hormones are more decisive than her grey matter.

However the profile of the culprit, that part was intellectually interesting.

The victims and their murderers are described in more detail than suits me.

The denouement left me cold. The villain was obvious for a long time to the reader, if not to Miranda. The complication of the religious zealot made little sense to this reader.

The author has other musical titles.

Igor regrets

Reading William Kristol’s string of repetitive laments on the arrested development that is Trump Donald is amusing. The most recent one I have seen is ‘It’s Not too Late – Trump must go.’ While one may agree with the sentiment, the source is tainted.

Kristol William

Kristol William

Nowhere in this weekly flow is there a mea culpa. Why should there be?

For those who missed the first act, Irving Kristol, William’s father, was a prime and proud architect of the Neo-Conservative movement. Its motto was ‘No more Mr Nice Guy’ and its practice was ‘Anything Goes,’ just ask Karl Rove.

Lie, cheat, steal, these are all acceptable activities in pursuit of the greater good, namely a Republican America from fifty statehouses to the White House. If Kristol senior was Dr Frankenstein, then Kristol William was Igor, eagerly and enthusiastically applying jolts of electricity to the living dead.

Lie, cheat, steal, these are all acceptable activities in pursuit of the greater good, namely a Republican America from fifty statehouses to the White House. If Kristol senior was Dr Frankenstein, then Kristol William was Igor, eagerly and enthusiastically applying jolts of electricity to the living dead.

As the Neo-Cons zombies rose, bipartisanship and civility fell. The Tea Party grew from this seed and that in turned spawned the Alt Right

It is recurrent theme in politics in the United States, xenophobia, anti-intellectualism, populist at the expense of institutions.

The inevitable, perhaps logical, outcome of this destructive approach to politics is candidate Trump Donald for whom there are no limits. He is the Alt Right candidate in Republican clothing.

These day not a week passes but Kristol William calls upon fellow conservatives, notice he no longer bellows his Neo-Con credentials, to do something about Trump Donald! Get the toothpaste back in the tube!

What fun it is watching this incubus squirm in his own juice!

Thanks to the Kristols and their kind, like Bill O’Nonsense, Murdoch’s Organs, and Fox Fairy Tales, we have come to this pass.

The party of Abraham Lincoln, the party of Herbert Hoover, the party of Wendell Wilkie, the party of Thomas Dewey, the party of Dwight Eisenhower, the party of Bob Dole, the party of John McCain,…..has come to Trump Donald.

I mention these men above because they were standard bearers of the Republican Party as presidential candidates.

A more complete list of noteworthy Republicans would also include George Norris, Arthur Vandenberg, John Lindsay, Earl Warren, Everett Dirksen, Margaret Chase Smith, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jacob Javits, Harold Stassen, Charles Percy, Olympia Snowe, Nelson Rockefeller, Arlen Spector, Nancy Johnson, and Christine Whitman. The list could be extended to many others.

Thanks to the Neo-Cons’ efforts to drive everyone else out of the party in the search for ideological purity, the Republicans are cut from the clothe that gave us Dennis Hastert. I could not find any pictures of this one in prison orange.

The ideology is simple: Anything goes.

The GOP is dead, but it still twitches with galvanic discharge.

‘Kolchak’s Gold’ (1974) by Brian Garfield

The genre is thriller but not the breathless, cross-cut, cryptic kind that conceals its lack of substance with smoke and mirrors.

In this case a historian comes across some undiscovered archival material. From this premise a mystery and a quest unfold. It is a reasonable premise since in its many convulsions Russian records have often been boxed up and sent off to the warehouses in the countryside and forgotten, because those who sent them died without time to leave records of the distribution. In the Kremlin treasury we were told many Tsarist gold bars were found buried in barn a few years ago in unopened boxes, stashed at least since the Civil War, each bearing the double eagle.

The exposition of the revolution, the communist coup d’état, and the Civil War was of especial interest to me as I read it while in Moscow, traversing museums and galleries rich in the detail of that period, having just done the same in St Petersburg. The factions, divisions, and differences among the White Russians goes a long way to explaining why they lost the Civil War. While they outnumbered and outgunned the Bolsheviks, they could never agree among themselves nor could they compromise with each other. As a result the Bolsheviks picked them off one-by-one.

The abdication of Nicholas II, accession of his younger brother Michael for one day and his replacement by Prince Lvov, then the liberal Alexander Kerensky, the ill fated Duma election that favoured the liberals and not the communists, the effort to continue the war which failed, and the coup at 2:10 a.m. in the White Dining room, which we visited where the clock stopped at that time.

My snap of the White Dining Room.

My snap of the White Dining Room.

The clock stopped at the time the door burst open.

The clock stopped at the time the door burst open.

The Romanov dynasty came full circle starting and ending with a Tsar Michael.

But the story is crowded and chops back-and-forth in time and place from those who stashed the gold, the Nazi effort to retrieve it, and our hero’s effort to track it down plus far too much of his back story, boring as usual.

Brian Garfield

Brian Garfield

We do get rather too much of our hero’s many other publications, offered no doubt to credential him. While his description of the Israeli femme fatale is nicely done, it does go on and on. It was clear to this reader from the beginning that she was a honey trap but the protagonist was much slower to realise that it was not his lengthy cv or other charms alone that kept her coming back for more. Oh hum. There is one born every minute, per the sage.

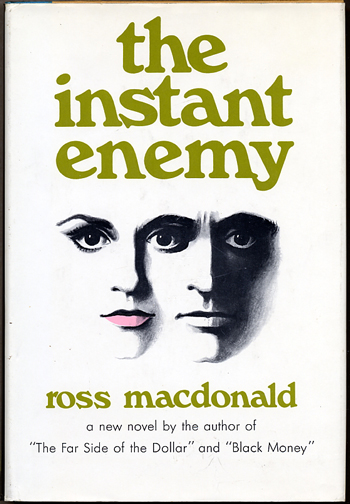

‘The Instant Enemy’ (1968) by Ross Macdonald

Another intricate krimi from this master, Ross Macdonald, he of California sunshine noir.

This is Macdonald’s take on the generation gap of the 1960s. Young Davy and even younger Sandy seem bound for mutually assured self-destruction while taking a few others with them.

Sebastian, Sandy’s father calls in Lew Archer to find them and return Sandy home. While Sebastian offers a good front, it does not take Archer long to realise there is no back to this front. Sebastian failed to make the transition from a promising young businessman to a successful one. Behind the trophy wife, model home, and new car Archer finds a loveless marriage, a silent house, and many unpaid bills, while Sebastian dances attendance on his wealthy boss, Stephen Hackett, in the hope of….something.

Then Hackett is kidnapped at gunpoint by none other than the two teenagers, Davy and Sandy. Unbelievable but true. Why?

It is a tangled skein and by the end I needed a genealogical chart because this one spans three generations. It is a cocktail of Macdonald’s themes, an unloved child, a misused child, illicit drugs, denied kinship, a surly subordinate, a very nice woman who knows too much, a venal older woman with a toy boy husband, and assorted police officers including a bent one.

The body count reaches Midsomer proportions while Archer develops, applies, tests, and rejects alternative hypotheses until at last one fits.

While the principle cast seems to consist of disparate people with nothing in common, in fact, on that family tree, they are entwined by marriage and murder, the latter seeming to be the stronger bond.

In addition to the rebels with a cause in the teenagers, Macdonald also adds some Cain and Abel. And as frequently the case in his novels, there is a black widow who has consumed two husbands.

Against the array of vipers and the lost teenagers, Archer meets some very solid citizens. Alma in the nursing home, a school guidance counsellor who goes beyond the call of duty, a security guard who keeps his word come what may, many others who lend a land, like truck driver who finds Archer on the highway, Al at the sandwich bar, and gas pump jockey with a calliper on his leg, each of whom reminds the reader of all the decent people out there.

The imagery at times transcends the story as when Archer admits to himself that he likes the work, late at night, driving from one place to another like an antigen connecting cells in the great body of Southern California.

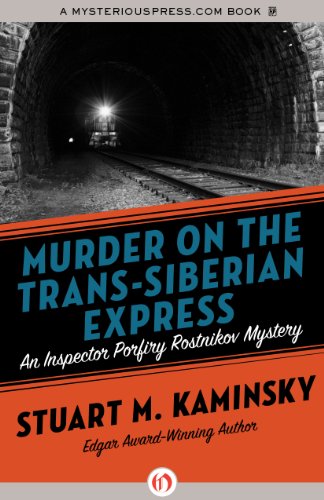

‘Murder on the Trans-Siberian Express’ (2001 ) by Stuart Kaminsky.

This title reads like short stories woven together, one of which concerns the Trans-Siberian Express. Only half-way through the book does our protagonist get on the train. The details of the train and Siberia read like excerpts from Wikipedia.

Though it is presented as a police procedural with the three teams of detectives working separate cases, pace Ed McBain’s 87th precinct, the ominous villain on the train and the plot that leads to the train is more of the thriller. Credulity replaces credibility.

The three stories are told back to front in alternative chunks of prose, which this reader finds confusing and distracting.

Though Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov is the central, continuing character in this series, endowed with an artificial leg to give him some distinction, I found him to be hallow. Tap, tap there is nothing inside. He is very polite, very patient, very clever…. he has a family…. our hero is motivated by justice but the boss is ambitious for political power and is more interested in accumulating files on those he can manipulate than banging up crims. So far, so carbon copy.

The three cases.

1. The subway stabber who is a nutter of no interest. This one is a procedural. Much plod and a trap that almost backfires.

2. The mysterious object on the train which turns out to be very little as far as I could tell. The thriller.

3. The kidnapping of the heavy metal musician whose kidnapping was arranged by his father to teach the prick a lesson. I identified with the father on this one.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

This is one of dozens of titles by this author, and to this reader it has the same narrative structure of the one other one of his I tried to read. All done by the numbers. Yet the cover proclaims it to be a best seller and it was published by a reputable firm. Go figure.

Stuart Kaminsky

Stuart Kaminsky

There are some soppy comments on the blanket of white snow in Moscow. Anyone who have lived in a big city will realise snow is usually grey like the sky until it turns brown from the pollution and churned up by cars and pedistrians into brown sludge. There is nothing nice about it after thirty-six hours.

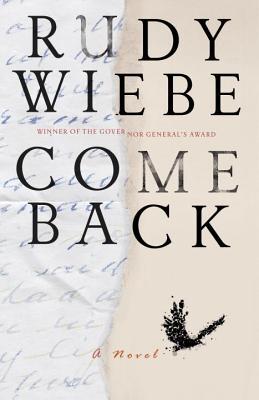

Rudy Wiebe, ‘Come back’ (2013)

This epistolary novel is a meditation on grief and mourning. It is low key, told in fragments and the more powerful for this episodic manner of exposition. At age twenty-five a man commited suicide and his father is thereafter haunted by this death.

Most of the story is told backwards as the father remembers his immediate efforts to understand the suicide by reading and re-reading every word his son left in letters, in noteboooks, in grad school assignments, anything else he can find.

This quest is sometimes played out before a chorus of one, Owl, his Cree, coffee-drinking friend.

It is set in Edmonton Alberta and the characters are Mennonites, very serious and spiritual people, from the vast prairies.

Rudy Wiebe

Rudy Wiebe

I used to see Wiebe on campus in grad school, and read one of his earlier novels at that time, ‘Peace shall destroy many.’ It was memorable. Much of this novel seems near the bone, almost autobiographical.