This is a novel about the lives and loves of a group of anthropologists at a London institute. For those who have to have a label perhaps we can call it a comedy of manners like Antony Powell’s ‘Dance to the Music of Time,’ the token that defined the type.

Tom, Deirdre, Digby, Catherine, Miss Clovis, Mark, Professor Mainwaring, Alaric, Rhoda, Professor Fairfax, Mrs Foresight, and others make a living sharply observing primitive peoples in Africa, while unconsciously acting out the same rituals in London. That makes it sound more didactic and pedantic than it is, but the cumulative effect is to observe the observer.

Only the visiting scholar, Frenchman Jean-Pierre, makes a point of observing and cataloguing English ways just as he would in the heart of Africa. Though he is unfailingly polite and far more considerate of others than any of his hosts, they regard him as odd.

The professional rivalries and jealousies all ring true but are played out with a polite formality. In all the author has a light hand.

The rituals of the off-print, when it still existed, are amusingly set forth. So that is what one was supposed to do with them, I said to myself! My collection of them grew to occupy a filing cabinet and I put them in a yellow recycling bin when I left the Merewether Building. I wonder what the ritual is now with PDF versions? No idea.

The centre of this little drama is Tom Mallow who is devastatingly attractive to women, which he takes for granted in a vague way as he ricochets from one to another, barely noticing the differences from Elaine whom he absent-mindedly jilted a few years before, Catherine who was mother and wife to him without the benefit of law, and Deirdre whose cow-eyed veneration warms him. Digby and Mark circle around in the hope of leftovers.

He is also the golden boy at the Institute, though he never seems to finish anything. That omission does not diminish his glow.

Alaric who has never published anything, though he treasures dozens of tea chests full of field notes, devotes his considerable energies to writing caustic reviews of the books others dare to publish. He never has a good word to say. Still less when book review editors sometimes alter his prose to make it less venomous. That elicits another war of words between Alaric and the offending editor.

All of this seems true to life, if from an earlier time.

One of the themes is the way we have of idealising and wanting the life that others have. The urban, educated, worldly Londoners pine for the suburban calm, snug family life of the provinces. The provincials lust after the allure of London and resent the claustrophobia of the Sunday lunch en famille. It sounds leaden when I write it but in the book it is a feather on wind, conspicuous yet ephemeral yet entertaining to watch.

Spoiler alert!

Tom, chronically vague and oblivious of his surroundings, absent-mindedly gets himself killed and Deirdre discovers that she recovers from the shock of the news of the death of this demigod in a few hours. Digby is so amusing. Catherine convinces Alaric to burn his field notes and so free himself of the burden they have silently imposed on him all these years. Professors Mainwaring and Fairfax begin another tug of war over a new golden boy. Miss Clovis shelves Tom’s thesis and goes to tea. Gone and forgotten in a very few minutes.

I first read it sometime in the latter 1980s or early 1990s and the volume came to light again in the course of moving to the new abode. At that earlier time I had meant to read more by Pym, but failed to do so. I will try to do better this time around and I have plunked another of her titles in my Amazon basket.

Pym wrote a number of such novels but then fell out of favour. She kept writing them but her publisher decided she was old fashioned and stopped taking them. Her efforts to find another publisher failed for the same reason: fashion, or the perception of fashion, from the editorial desk. Then in the later 1970s some literary lions (re)discovered her, and her books came back into print…to stay. I expect the editors who rejected her work were paid handsome bonuses for such insight, but their names are now forgotten.

Barbara Pym at work.

Barbara Pym at work.

She, by the way, was crushed by the rejection. This all from Wikipedia.

Author: Michael W Jackson

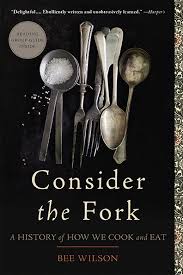

‘Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat’ (2012) by Bee Wilson

When I saw the title on this Christmas present from Herself, I thought of Norbert Elias’s ‘The History of Manners’ (1939). The book at hand is broader than its title indicates. The subtitle pretty well sums it up, however, I would have been tempted to call it ‘Consider the Kitchen,’ because that is the culmination of the book.

Each chapter focuses on some essential aspect of food and eating in one word titles: fire, ice, knife, fork, grind, and, finally, kitchen. The fork which I begin to consider is important, to be sure, but it is only one element among seven others, hence my quibble about the title.

Ever wondered why a kitchen knife is sharp only one side? A table fork has four tines? Why was the freezer on top of the refrigerator until recently? Why are tin cans of food the size they are? Why are refrigerators powered by electricity when they use gas? How did the can-opener evolve?

Probably not, we take everyday things for granted, but there is much to learn from the answers to such questions. Successful innovations started by pandering to the expectations of consumers as in the case of refrigerators. The influence of major industries also figures, as electricity powered refrigerators, a boon to power companies because refrigerators, unlike light bulbs, are always on.

Here are few tidbits. Japanese knives are sharpened to 20 degrees while most European knives are sharpened to 30-35 degrees. Why? The difference traces back to a combination of the use of the knife and the material it is made from. The carbon steel layers that combine in a Japanese knife take the sharper angle. Though it is dangerously, lethally sharp it is confined to the kitchen for preparation. European knives are made from a different compound of metals, and the use of the knife is not so strictly regulated by convention to keep it in the kitchen, e.g., Europeans cut meats and carve birds at the table in way unknown to Japanese cuisine.

Most interesting of all is, of course, the greatest technology of cooking, the kitchen itself. At one time food was prepared in a lean-to behind the house, now the kitchen is often, usually the centre of home-life. There is the amusing story of post-kitchen renovation depression, after years of saving for, planing, selecting appliances, designing a new kitchen, when it is finally done…there is nothing to occupy every waking hour. There is but a void.

Chopsticks are another world. The lacquered and pointed Japanese ones are impossible. The flat steel Korean one with small raised striations for gripping the food are the easiest to use. In between are the plain Chinese wooden ones, which are used in such a quantity to threaten the forests of the country.

The discussion of the potato parer is wonderful. We put up with that primitive implement for generations until someone whom she names came up with a better way. We do put up with a lot of inconvenient things because that is just the way they are, until someone comes along and betters them.

In the 1920s Marion Mahony at Castlecrag designed kitchens in the front of houses, looking into the street, to reduce the social isolation of the housewife eliciting the consternation of local councils, mortgaging banks, and some clients. Certain patterns are ingrained. This incident is not included in this book but it seemed relevant.

By the way, the fork is credited to Catherine di Medici when wed to King Henri of France and mother to his successor. She had a household of Italians to Paris and from there emerged the fork. Of course Italians had been using it for years but it only entered the food culture when it was used in France. Another example of ideology over reality. By the way, she is routinely blamed for the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants.

Bee Wilson wears a great deal of learning lightly, and passes much in review with no distractions. An attentive reader will notice that there are a few aspects of the contemporary food culture that she disdains but without ever quite saying so, a subtlety that will pass most by.

‘The Events’ – The Sydney Festival

We trained to Granville to see Scotsman David Greig’s drama ‘The Events’ at the town hall. It is a grim story of the aftermath of a mass murder, stimulated by that in Norway in 2011. In this case the victims, far fewer in number, are members of a community choir. It centres on the nightmares of a survivor, the choirmaster. Grim to be sure. Not our usual choice for a day out, but the chorine goes where there are choirs and I follow along.

it is a two-person show with a choir. One is the lead, Catherine McClements who mainly plays the survivor, and John Carr who does a variety of others. It is not always immediately clear who these others are.

The stage is devoid of props beyond a few chairs and a tea urn. Clever use is made of the chairs and tea urn as the scenes shift.

I liked the banality of the celebrity interview with the berserk Viking warrior conjured by the disturbed dreams of the perpetrator. It did seem just as trivial and egotistical as the interviews on the morning TV shows that I notice at the gym. John Carr did this very well.

I also liked the caustic reference to reality TV. Could not agree more.

Carr has to change personae several times and usually succeeds by body language, expression, intonation but not always. Oddly, perhaps his least convincing effort is as the perpetrator. He does the rightwing politician who stirs up the kind of hatred the perpetrator let loose very well: glib, smug, amoral, solipsistic, ambitious, all in one teflon package. Instantly recognisable without saying a word.

Several times there was smoke haze, that seemed to be the only stage effect. I was unsure what I was supposed to feel or think of that. Was it the gas residue of cordite? Most gunpowder these days leaves no such smoke, though fireworks still do.

The survivor is so tortured it is uncomfortable to watch. The playwright spares us some of this by breaking the story up into flash backs.

The choir, the victims, observe and occasionally sing, but not very much. It was not a Greek chorus as I had hoped, lacking the austere rigour of that.

The production started ten minutes late, and I wondered if somehow that was part of stage direction. If so, I enter a protest. It was unnecessary. If not intentional, I redouble the protest because professional productions starts on time, a thought I had when I looked at the ticket prices during the gap between published starting time and the eventual starting time.

The Granville Town Hall is an empty hall and only a spare production was possible. The acoustics were fine, as was the view. Getting in and out was easy and there was easy access to plumbing. All good.

We went early to be sure to be on time and by some quirk of fate we found our way to El Sweetie, a Lebanese shop recommended by a our neighbour.

Four starts ***** That alone will take us back to Granville.

Jarkko Sipilla, ‘Cold Trail‘ (2007)

A krimi set in coldest, darkest Helsinki in February. It is part of a set of titles called ‘Ice Cold Crimes’ with a set of authors from Finland.

It is a police procedural with much about the to’ing and fro’ing of the members of the Homicide Squad, set into motion when a convicted murderer escapes from custody. Intersecting with this low key pursuit is a traffic accident in which Lieutenant Kari Takamäki’s son is slightly injured, and he cannot help but intervene in this routine matter. There are also glimpses into the private lives of a couple of other officers, but the focus is mainly on the fugitive and his past. That is all to the good for this reader.

There is quite a lot of Helsinki in it, the streets, squares, buildings, residential high rises, the weather along with the organisation of policing, intelligence, SWAT,etc. The touch is light but definitive.

While most of the team is out questioning the one-time associates of the fugitive, one officer is assigned the homework of reading through all the files on the murder that led to his conviction and sentencing. In time, she begins to wonder if Timo Repo, the fugitive, was guilty, unpleasant, yes, but guilty, not so sure. To say more would be a spoiler.

Suffice it to say that the plot is well done and it ties together all the pieces of the story nicely, while delivering a few well deserved lashes to the unscrupulous news media and the perfunctory way unpleasant people like Repo are treated by lawyers and judges once they lay hands on them.

The book cover with that soft toy rabbit and the bloody hand have nothing to do with the story, as far as I could tell, but I did read it in bed as I was falling asleep….

While reading it I compared it to the latter volumes in Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s Martin Beck series as they descended into hysteria, mistaking their own ever greater self-righteousness for social criticism. By contrast, this volume is much more straightforward. All to the good. The police officers do their best, and in some cases that is not much, but in others it is more than enough. At the end when the SWAT team is set to go in hard and fast, its members would much prefer not to have to go. Too many guns and too much shooting is not the best or only way, they above all, know this.

Jarkko Siplia

Jarkko Siplia

Sipila has at least three other titles and in time I will get to them.

Bourne Morris, ‘The Red Queen Run’ (2014)

This krimi is the first of three involving Professor Maureen ‘Red’ Solaris in a college’s school of journalism. The dean of the school has died in a fall down some stairs over the weekend, Did he stumble or was he pushed?

There are many tensions within the school. The Old Guard is mortally jealous of its ancient privileges and prerogatives which the dead dean was eroding in reorganisations. Disappointed and disaffected candidates for tenure seem to be bent on destruction. Meanwhile, among the students, blackmail might be the route to an A+ result. Then there are the sexual assaults, divorces, and alcoholism. All and all, it sounds like a typical department. The only things missing, I thought, were embezzlement and extortion.

In fact, I found it all so real that flipped the pages, it being too much like being back at work: The special pleading from junior faculty, the one-eyed demands from senior professors, the requests of students for yet more concessions. If I wanted that, I could go back to work. It all seemed plausible, but that did not make it any more diverting to read. The only unrealistic element was the consideration and support offered by the corporate management at the top of the college to the beleaguered acting dean.

Professor Solaris is designated acting dean, and becomes involved in the snail-like police investigation. She then confronts the many psychopaths among the faculty and sociopaths among the students. At some point, I said a plague on all their houses.

Flipping the pages was made easier by the rather self-centred telling. The author identifies completely with Red and it shows. Her thoughts are cherished. Her love life sends quivers through the pages. Her fastidious habits are detailed. Oh hum. To this reader all of this was self-indulgent padding that advanced neither character or plot.

Bourne Morris

Bourne Morris

Not rushing to try volumes two and three, I am afraid.

‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (1992) by Sharyn McCrumb.

After reading her ‘Bimbos of the Death Star’ it was only a matter of time until I got around to ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool.’ When my Amazon Wish List came true on Christmas the time was right. It is an amusing and diverting lark as literati Marion and engineer Jay combine forces once again to get to the bottom of a mystery.

When frail Professor Erik Giles asks Assistant Professor Marion Farley to accompany him to a private reunion the fun begins. Jay Mega goes along to ride shotgun.

It is a very special reunion of a select group who were nutcase sci-fi fans in the distant 1950s. In the ensuing forty years some have made it big in books, in movies, in life and others have remained adolescent into old age.

The lore of fandom and tales of conferences past, the parade of sci-fi names, this book has it all.

Then one of the reunionist dies and the plot thickens. The old tensions and rivalries in the merry band emerge perfectly preserved in the amber of time. Secrets, long held and forgotten by some, seep out. Not good. The death was murder. Who done it? That is the question, Mr Spock, and the duo get to work on it tout suite.

With the schizophrenic Mistral leading the pack, along with the semi-comatose Surn, and the one-man avalanche Woodard, the phlegmatic Angela, the absent Earlene, lawyer Jim, the author has assembled a mix of folks and stirred the pot. The plotting is simple but clever, the dialogue sharp, and the setting vivid. Would that I could say even one of those things about most books.

The major theme is the disjunction between the expectation of fans and the reality of writers.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

There is one glitch: when the hotel manager thinks of the death as murder long before that has been established on page 175. He of all people would certainly has assumed that the old coot died of natural, old-coot causes.

The book has pace, place, and plot. Four stars.

Spoiler Alert! There are no zombies. There were not any bimbos either.

‘McGarr and Sienese Conspiracy’ (1977) by Bartholomew Gill

This is an early title in a long running series.

It is model of composition and structure, covering a vast amount of territory in few words.

A body is discovered in far Dingle at the southwest tip of Ireland, trussed, drugged, and shot in the head like an execution. McGarr travels from Dublin Castle to investigate. Only two days later, while the usual inquiries are underway, a second body is found in the same place, the police tape and seal having been ripped off to dump a second dead man, likewise trussed and shot.

McGarr takes this second murder as a personal affront.

The victims were both English and that takes McGarr to London. The prime suspects are involved in oil expiation off the Scots coast, both Italians with ENI, and that takes McGarr to Italy, and eventually to Siena.

The characterisations are vivid, the travelogue nicely done, and the dialogue credible.

To this reader there is too much of McGarr musing on the English and the Italians. Too much description of clothes and food in both places as well as Ireland. All padding which does little, if anything, to establish either place or character. Too much to’ing and fro’ing. And it is beyond credibility that police in England and Italy defer to McGarr like a demigod.

I would have much preferred more of Ireland. For Italy I can read plenty of Italian krimis which will be mercifully shorn of musing on Italians.

The denouement was pretty obvious and so contrived as to be boring. The involvement of Foster, the Jamaican, seems gratuitous. The helicopter flying woman is another red herring too far. Just by coincidence she flew nearly the same route on the same days with one of the same passengers, who seemed to be two places at once.

Bartholomew Gill

Bartholomew Gill

McGarr also muses about several women, and this, too. I found a distraction, all rather adolescent. One of these women, later in the book, is called not once but two or three times by the first name Graham. It is a typographical error, that being her husband’s name. Talk about distracting. I thought at first he had come back to life. A sentence that contains ‘she Graham’ should have alerted any proof reader.

Michael Booth, ‘The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia’ (2015)

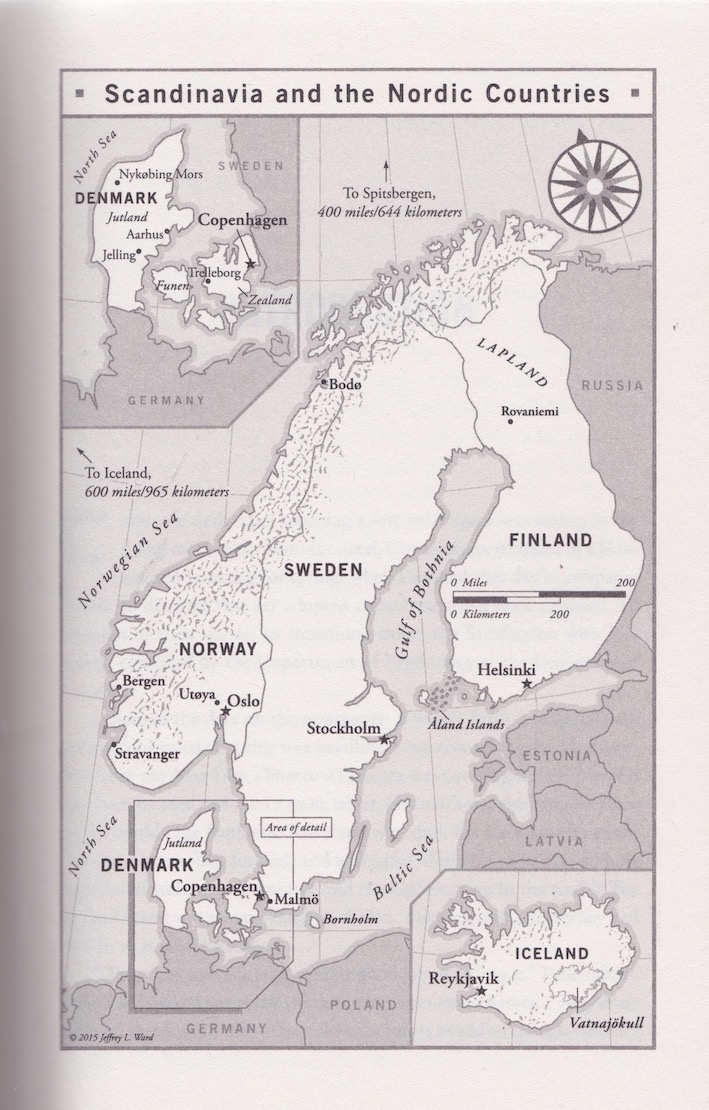

An amusing but informed, insightful, critical, positive, and biting though sympathetic tour through northern Europe. It starts with the definitions: no single term — neither Nordic nor Scandinavian — quite fits the combination of Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. ‘Northern Europe’ as a geographic term does not quite fit either, after all Iceland is way out there in the Atlantic all by itself.

‘Scandinavia’ does not include Finland, which has not participated in the Nordic Council and not in the Scandinavian Air Service, or NATO. As individual Finns are loners, so is their country. While the languages of the other four have much in common, not so Finnish. The Finnish language takes a lot of explaining, though grammatically it is, Booth says, simpler than most. It does not matter, since Finns do not use it much. He offers many examples of their taciturn nature. They are not the talkers that the Irish are. Their own term is ‘sisu’ which means just get on with doing it.

Iceland is the smallest, the most remote, the poorest, the most intimate, and all of that explains what they do and what happens in Iceland. There are a few snorts for reader when Booth samples some of the delicacies of Iceland’s cuisine. Iceland has long been very influenced by the United States and Great Britain, out that all by itself.

His analysis of Sweden as a mass society, my term, not his, has given me some food for thought. The explanation of the Swedish welfare state is that it makes individuals autonomous, i.e, they do not depend on each other [but on the state, yes]. Women are independent men; wives of husbands; children of parents, and so on. It is a benign decomposition of the civil society. What came to mind was William Kornhauser’s ‘The Theory of Mass Society’ (1959).

Norway? One word: oil. The wealth of the North Sea oil, despite the restraint exercised, has changed Norway and Norwegians, who now employ Swedish guest workers who peel bananas for them! Historic revenge against the colonial power! It is all explained in the book. See for yourself. The other distinction of Norwegians is their commitment to and engagement with the forests, fjords, and mountains of the country.

Denmark, where the author lives, is the odd one out. Perhaps because the author knows it best and he sees through many a veneer and what he sees, notwithstanding his efforts to balance the books, is not very pleasant. The courage to run that cartoon seems to have been born of a casual and still socially-acceptable racism, which often directed against migrants of any kind with the enthusiasm of a Tony Abbott. While successive Danish governments have been careful with the Kroner, Danes have not. The country has the largest private debt in the world, and its people work the fewest hours, and on every comparative measure of productivity rank low. It all seems rather fragile.

One of the strengths of the book is the use the author makes on the factual data available, e.g., to explode the myth, which I saw repeated just this hour on Facebook, that migrants are responsible for all, most, or any crime in Sweden.

He also makes good, though not systematic, use of the international comparative indices compiled by the Organisation for European Cooperation and Development, the United Nations, and non-government organisations.

The book seems to omit any account of the natives of the northern tip of the north, the Suomi peoples. They are mentioned but that is that. Who are they? How do they differ, how did they differ from Finns or Norwegians.

While Finland’s role as a buffer state, like Thailand between British and French colonies in Nineteenth Century south-east Asia, is treated, not much is said about Norway’s border with the Soviet Union and now Russia. Throughout the Cold War, Norway was the only western European state with a border on the Soviet Union.

There is no effort to define ‘utopia.’

Michael Booth

Michael Booth

The book is a salutory counterpoint to the personal reflections on Sweden in Andrew Brown’s ‘Fishing in Utopia’ (2009).

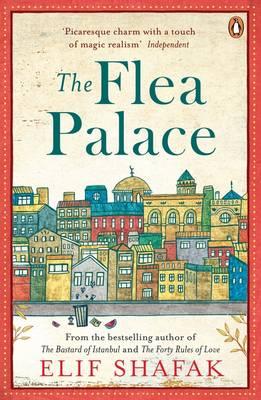

Elif Shafak, ‘The Flea Palace’ (2004).

Another item from my reading list for Turkey is this novel of 440 pages. It is well written and offers a cast of characters which represent some of the variety of life in Istanbul. There are many incidents, some great and others small, from the modus vivendi, so to speak, of the half-Moslem and half-Christian cemetery, the vanishing garbage, and the eponymous fleas. It is lively and, yet, well, I grew to resent having to spend my time reading it when I had such other alluring titles as ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (a treasured Christmas present from Herself) jockeying for my attention from the bedside table.

Despite the above remarks, there is no momentum in the novel. I was never quite sure why these characters were there and why I was supposed to invest interest in them. The assembly seemed to be arbitrary. Nor did I feel that, page-after-page, I was learning any more about any of them or the circumstances in which they lived. Instead the fevered imagination of the author produced yet another incident, twist, turn, upset, but well, since the prose was not going anywhere any twist or turn is just another twist or turn.

In so far as I got anything from it, it seems another exercise in ‘What does it mean to be Turkish’ that I found in ‘The Time Regulation Institute.’ Well do I remember all those talking heads on the CBC talking about ‘What it means to be Canadian.’ Same script here but different words. As Canadians have defined themselves by what they are not: American, British, or French, so some Turkish writers define Turkey by what it is not: European, Asian, Christian, Islamic. Not sure what the point is? Neither am I. Saying what it is not, does not leave what is.

I looked for other reviews to see if I had missed the point – it does happen. No professional reviews came to light and those I consulted, reluctantly, on Good Reads were, as usual, more about the reviewer than the book. Some liked it, but them some people like being hit with a stick. Others confessed that they had not finished it; my kind of readers, because I stopped, too. I am however grateful for one such reviewer who offered the summary below.

To make that summary meaningful I should say that the novel describes the live, loves, troubles, triumphs, lice, garbage, hair styles, reading habits, drapes of the assorted residents of an apartment building long past its prime, after an account of how it came to be built. The inhabitants who figure in the story are:

Flat 1, Musa, Meryem, and Muhammet: Musa and Meryem are married, but Musa is often absent. Their son is Muhammet who is a bullied at school, much to the distress of Meryem. Musa is no help.

Flat 2, Sidar and Gaba: Sidar lives with his dog, Gaba, and is obsessed with death.

Flat 3, Hairdressers Cemal and Celal: Separated as children, these identical twins are temperamentally dissimilar Cemal, who grew up in Australia, is a fussy extrovert, while Celal, who remained in Turkey, is painfully introverted. After reuniting, they run a hair salon on the ground floor whose staple is gossip about the occupants of the building.

Flat 4, The FireNaturedSons: This is a dysfunctional family dogged by ill fortune which tries to insulate itself from the others and, by extension, the outside world.

Flat 5, Hadj Hadj, his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren: Because the son and daughter-in-law work, most of the action in flat 5 involves grandfather Hadj telling his grandchildren stories which bore the oldest and confuse the youngest.

Flat 6, Metin Chetinceviz and HisWifeNadia: Metin isn’t around much, but HisWideNadia is: she’s a Russian émigré with an unhealthy obsession for bugs and a dubbed Latin American soap opera, ‘The Oleander of Passion.’

Flat 7, ‘Me:’ The narrator is a recently divorced university professor who think he is perspicacious. [The author is also an academic.]

Flat 8, The Blue Mistress: She is a kept woman for a merchant, which the neighbours accept despite the teachings of the Koran.

Flat 9, Hygiene Tyijen and Su: Hygiene is a compulsive clean-freak. Her daughter Su has lice, and that drives Hygiene to new heights of cleanliness.

Flat 10, Madam Auntie: The aged matriarch of Bonbon Palace, whose story only reveals itself towards the end, or so it is said. I cannot confirm this assertion since I ended my reading before the book ended.

The author has many other titles. Ahem. So be it. She also proclaims a PhD in political science. [Sounds of silence.]

More on ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ later!

‘Decision at Sundown’ (1957)

Here I am again with another Randolph Scott western movie. This time he plays against type, though it took this viewer a while to realise that. The certainties of the western genre are used as a foil to go further and to go deeper.

Bart Allison (Randolph Scott), is slowly revealed to be a crazed obsessive who stubbornly persists in his destructive ways against all evidence and reason.

Moreover, it is also against genre since westerns invariable take place before a background of wide open spaces. Not so here, where nearly all the action is confined to one cramped interior.

But wait, there is more! It is also against type in the portrayal of the villain, Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll). He certainly seems to have the town under his thumb, but he seems to have accomplished that with some greasy charm, a wad of dosh, and veiled threats, nothing more. As it turns out, the villain is not guilty of the heinous crime, Allison supposes, but Allison will not hear the truth nor accept that exculpation, not even from his best friend, Sam, played by the ever-charming Noah Beery, Jr.

Only later does Allison seem, at least for a few seconds, to realise his colossal folly, but even then he persists in his mad quest for vengeance. This is one of Randolph Scott’s darkest role, made all the darker by the expectations audience bring to his films.

The counter point to Allison’s moral disintegration is the gradual moral reintegration of the town’s people to throw off the yoke of Tate Kimbrough. Shades of ‘High Noon’ (1952), though the threat there was far more visceral and immediate.

The town doctor is a one-man Greek chorus who comments on the folly around him without getting involved in it himself.

In the end there is mano-a-mano shoot-out in the great tradition of the western, but this one has a surprise result. The last line of the film from the doctor says it all. See the film to find out about both the surprise ending and the last line.

The cast is full of familiar faces from 1950s television from the sheriff to the bartender, the barber, the banker, and more.

It offers lessons for film makers any time. In less than 80-minutes we have an ensemble cast, vivid scenery, much debate, some soul searching by both Kimbrough and Allison, violent death, and true love.

There are plot holes here. In the first scene, why is Scott in the stage coach, and why is it necessary for him to stop it with threats to meet his partner? Why could he not get a horse and ride to the meeting? Or why could he not arrange for the stage driver to stop at the locale he wanted, and just get off? Perhaps his threats to stop the stage are meant to indicate just how unreasonable he is to become later.

In the town of Sundown, how did Tate Kimbrough establish his hold? What about him led the decent and upstanding Lucy (Karen Steele) to want to marry him? (There is no affinity between them in a few scenes they share.)