This is the twenty-first novel in which Richard Sharpe’s career is recounted by a master story teller. As a teenager, Sharpe’s career started in India, but in these pages he is nearly forty, called once more into the breach.

The wife of an old friend solicits the assistance that only Sharpe can lend to find her husband, who has been lost in the fog of war in rebellious Chile in 1820-1821. He reluctantly leaves home and hearth in his farm in Normandy. It is a common set-up made fresh in Cornwall’s hands.

En route to distant Chile his ship calls stops for water at St. Helena. There Sharpe meets face-to-face the nemesis that has dominated his life from 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte. In the company of a group of a dozen Spanish officers with whom he is travelling, Sharpe is received by the Emperor. This scene is well realised. While everyone in the room is an officer, the Spaniards all decked out in grand uniforms for the occasion, there are only two soldiers in the room, and each recognises the other as that almost immediately. After some polite formalities Napoleon dismisses the gaudy Spaniards, so that he and Major Sharpe in a faded field jacket and he can talk about …,well, what else, Waterloo. For his part, Sharpe clearly sees in the sallow, pudgy little man, the inner warrior.

As well done as that is, at the time it seems window dressing, but read on.

In Chile Sharpe finds a mare’s nest. The Spanish officials range from incompetent to corrupt. The British consul is a useless. The rebels are not any better, back-biting and bak-stabbing.

Sharpe’s perception of the Spanish colonial administrator is insightful and amusing. He enters a room to find the governor surrounded by officials. Each is intense and focussed, none more so than the Captain-General Bautista.

“The Captain-General had resumed pacing up and down …stabbing more questions into his audience as he paced. How many cattle were in Valdivia’s slaughter yards? Had the supply ships arrived from Chiloe? Was there any news of Ruiz’s regiment? None? How many more weeks must they wait for those extra guns? Had the Puerto Crucero garrison test-fired their heated shot, and if so, what was their rate of fire? How long had it taken to heat the furnace from cold to operational heat? It was an impressive display, yet Sharpe felt unconvinced by it. It was almost as if Bautista was going through the motions of government merely so that no one could accuse him of dereliction when his province vanished from the maps of the Spanish Empire” (p. 88).

A few pages (p. 91) later the Captain-General outlines his strategy to defeat the rebels, which is to build ever larger fortifications and lure the rebels to their deaths before the cannons, if only Spain will send him more men, cannons, ammunition, and artillery men. It is, as Shape muses a strategy of doing nothing and shifting the blame for the result onto others, not enough cannons, not enough ammunition, poor artillerymen. In short, he has no strategy. The puff seems plausible because of the theatrical presentation. Why does this remind of briefings from some of my leaders? I could not possibly say.

The action scenes are so energetic that the reader suspends disbelief due to the momentum of the prose. Cornwall knows how to do this. The small rebel force succeeds by subterfuge, guile, surprise, and audacity and more audacity. It succeeds because the Spanish are poorly trained, poorly led, poorly equipped with rock bottom morale. While the Spanish have sturdy forts and many cannons, they have no reason to fight so far from home, being well aware of the corruption of their leadership. While the rebels are resilient, the Spanish are brittle. This, too, Cornwall does well.

Bernard Cornwell

Bernard Cornwell

In addition to Sharpe, Cornwall has also published another many other novels on a variety of other themes from the Saxon Trails to the Copperhead Chronicles. Then there is the non-fiction. Wow!

The idiom a ‘mare’s nest’ traces back to the Sixteenth Century where it meant something extraordinary and remarkable. Indeed too remarkable to be a true, a hoax. By misuse, that god of idiom, came to mean something extraordinarily complicated and confused.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘Kepler’ ( 1993 ) by John Banville

A novel with that super nerd Johannes Kepler in the leading role. It is part of a series of such eponymous works by the tireless John Banville, on whom there will be more later.

The young Kepler, having exhausted alternatives, goes to work for the great Dane Tycho Brahe who is sustained by that screwball emperor of the vestigial Holy Roman Empire, Rudolph II in Prague (been there). In so doing Kepler’s backstory unfolds in several flashbacks.

Kepler is a teacher whose tenure is precarious in a world still riven by the Great Schism and where schools exist at the whim of the local grandee. He marries largely for the dowry which is quickly spent on an inadequate model of the planets. His wife Barbara is seen only through his eyes as part whore and part harridan.

Brahe is a remote and glacial figure who treats Kepler as an underling, not a colleague. Tyco is moody, vague, and irascible by turns. Hardly the ideal patron, but Kepler has no alternative but to bear it. Rudolph is seldom seen, and exercises no influence, it seems. He just lets Brahe get on with it.

The atmosphere is laid on by the cement mixer load and gets in the way of both the plot, if there is one, and character development, if there is any.

The author tries too hard to create a foreign world by reaching for the dictionary and using as many an arcane words as possible each of which distracted my attention as I looked each of them up. Moreover, I soon lost patience with Kepler’s tongue-tied ineptitude. He blunders about like one of the Stooges alienating even his supporters. Now that may been historically accurate portrayal, but it does not inform, entertain, or enlighten a reader.

When he is offered the chance to explain his system to a patron (and thereby to the reader), he does not seem to know what to say and starts with the most minute details, quickly boring the auditor, and this reader, too. It is as though Kepler does not know the point either. I wondered if Banville was trying to show this as an example of pure research scoffed at by practical people, but if so, it fails. All I got was the urge to shake Johannes and tell him to get to the point, whatever it is.

Towards the middle of the book one finds a series of letters written by Kepler and the man revealed in these letters is not the bumbling oaf of the preceding pages. The letters are succinct, clear, and revealing. I do not know (yet) if they are real or imagined, but they are a relief of the clown Kepler of the earlier pages. Then in the last third we have Kepler again, not quite as bumbling and irritating. There is no explanation for the insertion of the letters and no indication at the end about their veracity. While there is an end note that mentions a biography of Kepler there is nary a word to explain Banville’s caricature.

John Banville is a one-man industry with scores of books to his credit under a phalanx of pseudonyms, or so it seems. He writes contemporary novels, mostly set in Ireland under his own name, krimis featuring Dr Quirk under another name, still others as Benjamin Black, and this series of biographical novels about great scientists. It must be in the blood since his brother Vincent is also a busy author-bee, too. Sadly nothing in this book motivates me to read another.

John Banville is a one-man industry with scores of books to his credit under a phalanx of pseudonyms, or so it seems. He writes contemporary novels, mostly set in Ireland under his own name, krimis featuring Dr Quirk under another name, still others as Benjamin Black, and this series of biographical novels about great scientists. It must be in the blood since his brother Vincent is also a busy author-bee, too. Sadly nothing in this book motivates me to read another.

There was some added interest in that much of the novel takes place in Prague on that hill, which we visited in 2014. We walked through some of the rooms where Kepler worked. Moreover, that odd specimen Rudolph II, Holy Roman Emperor, is a character. This Rudolph sponsored all manner of invention and science. There is an excellent account of him in an ‘In Our Time’ episode from Lord Bragg. I have not been able to locate a biography of Rudi.

‘The Murder of Adam and Eve’ ( 2014) by William Dietrich

Two teenagers, aged 16 and 17, are chosen by aliens to justify the existence of humanity by preventing the murder of Adam and Eve. Such a trial of poor old humanity is a common premise in science fiction. Consider the Q Continuum for one.

That old chestnut is given a new twist in these pages by sending the pair — Ellie and Nick. — back in time to 50,000 B.C. to save themselves by saving the genetic forbearers of our species in East Africa, styled Adam and Eve.

Nick has all the egotistical misery and self doubt of a normal teenager, while Ellie is several classes out of his league, pretty, smart, decisive, and confident. Nick is a loner with few interests. But together they make something of a team, the more so with a box of matches, a Swiss Army knife, and few other things in their pockets when the trial began, but their greatest asset is Twenty-First Century knowledge (hygiene, maps, the wheel).

Yet for all their several advantages they have a lot to learn about living in Eden, stay downwind of the animal herds. That standing still while a lion passes in the distance is very hard when the fire ants swarm.

They do find the genetic bearers whom they call Click and Foxy, and they do try to protect them and also get them to move toward Sinai thanks to their Twenty-First Century knowledge of maps and cross into the Middle East in time to come.

In the course of these exertions they learn to kill, butcher, and eat, sometimes raw, wildebeest and other delights of the teeming flora and fauna. This is no place for vegetarians, vegans, lactose intolerants, etc., etc. They also learn to trust each other, and slowly win the trust of Click and his clan.

Woven into the story are comments, too many for this reader, about the dire straits of the environment in the Twenty-First Century and the looming environmental catastrophe that threatens the Earth. The self-destruction of planet Earth, a perfectly good piece of real estate, is what has prompted the aliens to intervene, thinking to reset this world by extinguishing Click (Adam) and Foxy (Eve) and let evolution start over. This is a clever idea for a plot.

There are two sub-plots to muddy the water, though the major twist was evident long before its revelation. Even so it was well done.

The suspicion of my acne years that high school science teachers are not human was at last vindicated.

Dietrich has a good ear for teen-speak though it is mercifully shorn of speech crutches of ‘like’ and ‘actually.’ Though the latter has long since migrated to adult speak. Quarantine failed on that one. He is even better at getting inside the mind of Nick, whose high school experiences perhaps reflect Dietrich’s own. I know they do reflect mine.

William Dietrich who is an accomplished writer whose Nathan Gage I have much enjoyed.

William Dietrich who is an accomplished writer whose Nathan Gage I have much enjoyed.

‘The House of the Mosque’ by Kader Abdolah (2010)

This book is a novel. Aqa Jaan and his family live in a house attached literally and figuratively to a mosque. In fact his family owns the ground upon which the mosque was built. Imams come and go but the Jaan family goes on and has done so for hundreds of years in the house of the mosque.

The story opens in the latter days of the reign of the Shah of Iran and ends twenty or so years later. That is, it encompasses the origins and start of the Iranian revolution that toppled the Shah, started a civil war among Iranians, led to a war with Iraq, and blood letting without end, all the while praising the God of peace. In pauses during the slaughter, there is much praying.

Leaving aside the details, the account has many, many parallels with the French Revolution, the Russian revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and no doubt others from Cuba to China and back. First the uprising, followed by increasingly brutal repression. Then victory for the revolutionaries followed by a purge, first of previous enemies, and then of tepid friends, and then as the paranoid of incumbency develops a cannibalism its own. Remember Robespierre? Revolutionaries eat their own.

Under the guise of the New Dawn, old grudges re-surface and old scores are settled with revolutionary justice, i.e., a bullet to the brain right here, right now. Anonymous denunciations are enough. Silence is betrayal. Any criticism, or hesitation is treason.

Some estimates of the death toll exacted by the Ayatollahs at 60,000. The Iran-Iraq War added another 1.5 million deaths. Iran being roughly four times larger than Iraq its military strategy was to win the war by piling up corpses. It was the same strategy General Alexander Haig favoured on the Western Front in World War I.

Aside from those generic features, the portrayal of the Ayatollah Komeini is interesting, and there is some explanation of the factions that existed in Iran before, during, and after the revolution.

The trials and tribulations of the Jaan family are without end, though somehow a few of them survive and retain their faith in Islam despite its bastardisation during and after the revolution. As for many others, their faith is in God, not in the church.

Some gratuitous grostequieres like the Lizard.

I read it as an Ebook on the Kindle which means only saw the cover once in a poorly rendered graphic. Ergo when it came time to type these notes I had to make a point of opening the cover to get the title right and to get the author’s name. On the title page I could not find the year of publication.

Kader Abdolah

Kader Abdolah

Translated into English from a Dutch translation. Odd that, I would have supposed the best thing is to translate from the original into English, not from Farsi to Dutch to English. Having said that, I found no faults with the translation, but then I might not but someone who knew Farsi might.

It was hard to keep track of characters because of the unfamiliar names, like those in nineteenth century Russian novels, and the over lapping webs of the extended family and the mosque.

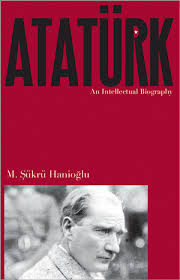

‘Atatürk: An Intellectual Biography’’ (2011) by Şükrü Hanioğlu

When in New Roman do as the New Romans do, I said to myself, and downloaded this biography while in Istanbul, which, when it was Constantinople called itself New Roman. (We were told the city never styled itself Constantinople, that being a nickname that stuck when Emperor Constantine ruled.) Atatürk (1881-1938) is the name that everyone associates with Turkey. Who was he? What did he do? Why did he do it? These are some of the questions that come to mind.

He was born in Salonica, and there is the first irony, Salonica today is Thessalonica, the second largest city of contemporary Greece. This fervent Turk and founder of Turkey and unremitting enemy of Greece was born there.

HIs parents were ethnic Turks. His father looked to the future and saw Europe while his mother looked to the past and saw Islam. She wanted the boy to go to a Mosque school where the curriculum was the Koran. The parental compromise was for young Mustafa to go the Mosque school for the first two years and then to a public school. That is the sum total of his exposure to Islam.

At fourteen, on his own initiative, he applied to and entered a military academy because he wanted to learn mathematics, science, engineering, and languages. These subjects were taught in the military academy and not in the impoverished normal schools. There began his military career on a foundation of Enlightenment science and rationality. He had an enormous intellectual appetite and became a lifelong autodidact, cobbling together ideas and facts from a range of discordant and sometimes unreliable sources.

He entered the army of the Ottoman Empire, a large, ramshackle assembly of peoples and places from Libya to Yemen to Saudi Arabia. It was polyglot and dilapidated. The Arab peoples far away from Istanbul were restive, but more pressing were Greece and Russia on the borders.

The young Mustafa saw combat in border wars with Greece and Bulgaria. He learned some lessons. Both the Greeks and Bulgars had national and ethnic unity. The Ottomans had the Sultan. Moreover, thanks the tacit support of Great Britain, the Greeks had modern weapons – rifles not sabres.

Then came the big one, the Great War. The Ottoman Empire blocked Russian access to the Mediterranean Sea and held vast territories that were oil rich. It was engaged in the Great War with the Russians to the North, and with the British in Mesopotamia, i.e., Iraq and Palestine, with the Greeks in the Balkans, with the Italians in Libya and Eritrea. The list goes on.

Mustafa commanded a garrison on the Dardanelles, frustrated that he could not get into the action, and then the war came to him with the Allied attack at Gallipoli.

There followed eight months of near continuous battle with a combined force of British, French, Australians, and New Zealanders. Mustafa proved a master tactician, for though he had superior numbers his troops were not trained and were poorly armed and equipped. His used the terrain and local knowledge to anticipate the Allies manoeuvres, landings, and assaults. He resisted both the pressure of his German military advisor to withdraw to an area where he could use his larger army to crush the Allies, and the pressure from the Sultan to throw his men into suicide attacks to drive the infidels into the sea.

In January 1916 the Allies quit and Mustafa became the man of the hour. This was the only victory for the Ottomans and he was lionised, even as the Ottoman Empire disintegrated.

The Sultan became a figurehead for a cabal (which the author implies was responsible for the Armenian genocide) which sued for peace at any price, thereby alienating many natives. The Allies occupied Istanbul well into 1921 on the ground of controlling the Bosphorus and thereby sealing off the emergent Soviet Union from at the Mediterranean during the Civil War between the Reds and Whites. The Sultan was in effect a prisoner in a gilded cage.

The war hero Mustafa convened a Turkish Grand Assembly in the dusty town in the middle of Anatolia, at first to rally a force to push the Allies out and restore the Sultan to authority while defending the faith of Islam. While all this was going the Arab states hived off the Ottoman Empire, and left a more homogenous residue and freed Mustafa to purse an increasingly nationalist program.

There was another war with Greece, and once again Mustafa prevailed to hang on to Rumeli (the European rump of Turkey, the word is a corruption of Roman). His trials by fire made him legend, and he learned quickly how to exploit it.

He promoted the idea that Turks were the first people and that humanity spread from central Asia, and that these were Turks. In this account the ancient Greeks derived from Turks, as did everyone else. He promoted a racial identity as the key to nationalism, thereby excluding Jews, Kurds, Yazidis, Arabs, and others in the remnant of Turkey.

With top down social engineering he tried to make Turkey into a Western European country by creating a Turkish language and alphabet to replace the Persian-Arabic script, by starting free public education, by minimising Islam, and by much more. He made that dusty town in central Anatolia the capital and named it Ankara which today is a modern European-looking city. He banned the veil for women and promoted European dress for women as well as men. His efforts predated those of the Shah or Iran to do something similar in the 1960s and 1970s.

None of these efforts at the social engineering went smoothly. The language change was bungled and took years to resolve, with the result being a Roman alphabet with a thick undergrowth the accents that is not the simple, rational creation he wanted. Islam withstood his efforts even during his lifetime. He lost the battle of veil and had to relent.

But his changes did create an enduring social and political elite akin to those of Western Europe, especially in the big cities of Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, and Bursa. This elite is larger and more varied than that terms includes in most other European countries, the author claims but does not explain. Some say today there are three Turkeys: Istanbul the city-state is one, the remainder of coastal Western Turkey is another, and Eastern Turkey the last.

His government was authoritarian though cloaked in the rhetoric of a republic, a free press, equality before the law, and parliamentarianism, but woe betide anyone who criticised Mustafa Kemal Atatürk who had a thin skin. Newspapers were closed, journalists arrested, and some unionist were murdered. Bad as all that was, compared to his contemporaries in Germany, Italy, and Spain it was mild.

Five percent of the members of his last parliament were women. Not much, right? Well it was more than any where in Europe at the time, and no later parliament in Turkey had as many women until 2010.

Though not invoked by the author, it is clear that Atatürk saw himself as a latter-day philosopher-king making a society anew from his brow. Of course, he would not footnote Plato, a hated Greek. He had a formidable brow along with blue eyes.

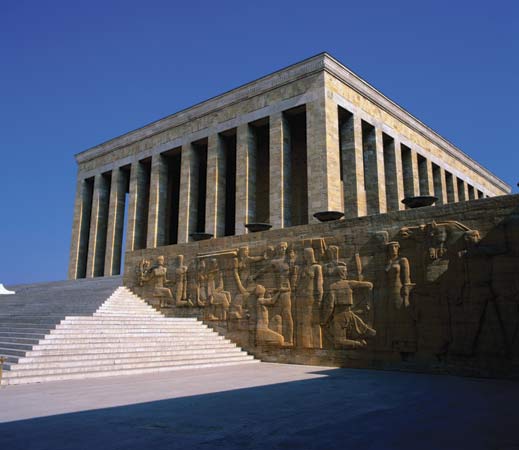

The Ataturk tomb in Ankara.

The Ataturk tomb in Ankara.

The book is true to its title. There is little of the man’s life beyond an outline, and nothing about his formative influences, private life, or inner personality. The bulk concerns his efforts to compound a pseudo-scientific Turkish identity. The author treats the subject with an even hand.

Şükrü Hanioğlu

Şükrü Hanioğlu

Appendix: The Gallipoli invasion, so maligned in Australian history, was the only strategic initiative of World War I. Its purpose was twofold, first to open the Mediterranean Sea to Russia to keep it in the war and second to force the Germans to weaken both the Western and Eastern fronts by diverting ever more men and materiel to the Middle East. In the course of planning and organising the invasion, Winston Churchill’s original plan was substantially altered, leaving fewer ships and fewer men.

The ANZAC landing was intended to cut-off Turkish troops that had gone down the peninsula to attack the British and French landings. But things went wrong. Troops landed in the wrong places. Misfires reduced the naval bombardment to a few shots. While Australian love to blame the Pommes it is true that the British and French each suffered a greater death toll that the Australians, though no one in Australia seems to know this, ever happy to be victims.

‘Napoleon’ (2014) by Andrew Roberts.

I have read three very large biographies of Napoleon and found myself none the wiser. They were records of events with little or no insight into the making of the man in his youth, what drove him ever onward in maturity, or the talents that enabled him to do what he did.

There are more biographies of the Corsican than can be counted. Which to choose? No point in re-reading the three I had already been through, so I went shopping! I chose this one because the description emphasised the evidence the author used, i.e., contemporary letters, diaries, and reports, as well as Napoleon’s own letters, essays, and manuscripts. In anticipation of travel, I loaded the Kindle with this 890 page tome.

Indeed, the book opens with an impressive critique of the primary sources that have influenced many other biographies by showing that some accounts by Napoleon’s contemporaries and associates were written… forty-years after the fact, by the grandson and not the principal, based on nothing but memories of an eighty year old who did not keep a diary, produced by a fraudster and not by the man named on the cover, or comprehensively changed in translation by demonising Napoleon to suit English readers. Many memoirs of his contemporaries were very unreliable.

While I cannot judge the veracity of these assertions, they did convince me that this author is interested in evidence more than malice or gossip, which marred the earlier biographies I read.

Here are some of the things I learned.

1.The primacy of the family, a residue of Corsica where it was us-against-all. He stuck with his family members long after they proved to be liabilities.

2. His earlier aptitude for mathematics got him into military school and then the artillery. He long retained that analytic approach to his thinking.

3.His varied but indifferent early service in the Royal and then Revolutionary Army.

4.His decided to be French, and not Italian, or even Corsican. He spoke French badly and wrote it worse.

5.When the Revolution and the Terrors came each thinned the ranks of the officer corps leaving plenty scope for advancement for an energetic officer like the young Napoleon. Energy is one theme. He did sleep seven hours in a twenty-four but seldom in one stretch. He often dictated letters or travelled at 3 am.

6.He spend two years on assignment at the topographic office of the French Army in Paris, which was the de facto General Staff, where four old, experienced, and successful generals war gamed old battles and fictional ones, too, while Napoleon looked and learned. He had a prodigious memory. Thereafter he always collected and compiled maps.

7.In his first field command he created the post of Chief of Staff to manage the stage machinery of logistics and continued that ever after. The result was that his armies had greater mobility than his opponents because they had better staff work.

8.As commander of the fifth-rate French Army of Italy at twenty-six he encountered and bested three Austrian armies, each commanded by generals over seventy. They thought slower, moved slower, had more cumbersome ties to the political leadership, than Napoleon who acted first and explained later.

9.He acted in excess of his orders on the gamble that success would exonerate him, and it did.

10.While the political leadership did not trust any successful general, it needed the money he harvested in Italy and so kept him in service.

11.He filled his reports to the Directory in Paris with (A) exaggerations of his victories which went unchallenged as long as he sent along with them gold and loot and (B) misinformation about the Austrian generals he faced, praising the incompetents and deprecating the able, on the assumption that Austrian spies would read them and that Vienna would then keep the fools in command and replace the able. He continued to practice disinformation of several kinds on all of his campaigns.

12.He developed diamond manoeuvres, which I do not fathom, to allow his troops to adjust to line or column on the battlefield with ease. The innovative formations and rigorous training made his armies superior men-for-man.

The honey bee was his emblem.

The honey bee was his emblem.

13.It is unlikely that he ever said that an army marches on its stomach but he knew it marched on its feet and spent a great deal of time and effort in getting boots for the troops. More than once, the terms of surrender he dictated to a defeated opponent involved shoe leather.

14.He published army newspapers to circulate among the troops which told them why they were fighting, both to defeat predatory enemies and to spread the enlightenment of the Revolution, and praised their deeds. The troops sent these cuttings home to show relatives how important they were.

15.To raise morale he awarded recognition to regiments, usually a motto, which was then sewn on the flag of the regiment. He created other honours and awards to stimulate patriotism and unity.

16.Made himself available to hear petitions from individual soldiers, and was generally very lenient with them while being stern, harsh, and demanding with officers, especially generals. There are some remarkable accounts of him striking up conversations with soldiers on sentry duty, wounded on battlefields, and other common soldiers. The author is sure no other general, not even in the French army, let alone in the Russian, Prussian, Austrian, or English armies of the time, would ever even recognise a man in the ranks. Once he met a solider he would remember him the next time.

17.He devoted resources and time to medical care for the wounded, and later pensions for widows, and payments to the incapacitated. Another theme in peace terms was medicine for his wounded.

18.As First Consul he stopped the bloodletting of the Revolution, invited home emigres, aristocrats, released from prison all political prisoners, and asked exiles to return to France. He appointed overt homosexuals to government posts, as well as Jews, Protestants, and atheists. Loyalty to France and then to himself, these were all that mattered.

19. He imposed Enlightenment rationality and universality to weights and measures, made French the official language rather than Occitan, Catalan, Basque, Breton, Norman, Italian in Nice, Dutch in Dunkirk, German in Alsace.

20.The Code Napoleon revolutionised, simplified, and rationalised the law, reducing the law from 5000 pages to 55 pages of principles.

21.He created scientific institutes and libraries some of which are still in use today.

22.He was a one-man Enlightenment for France in his early years with colossal energy.

23. Most fascinating to me was his ability to switch from one subject to another without a pause. While riding onto the field at the battle at Auerstadt he dictated a memorandum about building a girls’ school in Paris. There are lot of examples of this micro-management in the midst of battles.

24. His greatest military success was the bloodless battle at Ülm, where by a combination of speed, deception, and training his army completely surrounded a larger Austrian army which then surrendered. It was an astounding event.

25.He never understand the first thing about ships, oceans, navies. Indeed, he was convinced, and no amount of explanation could change his mind on this point, that the English naval blockade of Napoleonic Europe weakened England.

26.He found the coalitions he faced were divided by language, by goals, by opinions, even by calendars (Julian or Gregorian), munitions (calibers differed), formations, and so on. Each was a weakness which he — the single mind — exploited while they bickered and passed blame back and forth.

27.Personally he was courteous, calm, and heard out criticisms and alternative points of view. Not the raging tyrant of British propaganda. Though assassination attempts made him ever more paranoid.

28.The destructive invasion of Russia was precipitated by Russian complicity with England to break Napoleon’s continental system, despite a treaty affirming Russian compliance with it.

29.Napoleon’s plan was a month long campaign with battles on the border of Russia, and then a peace. Thereafter, step-by-step he went further in and then tarried. Long before General Winter struck, even more devastating was General Typhus.

30.The enormous army he took differed from the others he had led to success. First and foremost it was bigger than anything he had commanded before with attendant complications of logistics, communications, and movement. Moreover, the garrisons in the Napoleonic Empire from Portugal to the Danube absorbed 400,000+ troops. To staff the invasion army of 600,000+ he depended on contribution from seventeen allies: Bavaria Württemberg, Baden, Saxony, Hesse, Holland, Brabant, Spain, Basques, Catalonia, Poland, Hungary, Mamluks, Arabs, Romans, Milanese, Lombards, Naples, Slovenes, Swiss, and so and on. Altogether they offered a cacophony of languages, uniforms, procedures, calibers, food preferences, and motivations. About half of the invasion army were mercenaries, i.e., not French. It was divided by language and many of the troops from client states were not motivated.

31.Much of his earlier success sprang from the unity of command, the identity of training and weapons, and the speed of his army which he motivated with patriotism. In addition,nearly all of the generals he had opposed before Russia had been septuagenarians who had to get permission from a political leader before moving. This time the Russian Tsar was with his army and many of his generals were in their 40s.

32.His evolution into an emperor and a dynasty was partly to provide continuity and stability. When Alexander the Great died there was no successor and the result was civil war, ditto Caesar. He had also seen popular governments in French itself and in England pulled this way and that by tides of opinion. A monarchy would arise above those divisions provided it was constrained by a constitution. It sounds very like Georg Hegel’s account of a German constitution. Of course, it all rests on the assumption that Napoleon, Junior would be competent.

33. He seldom drank wine and did not drink Napoleon Brandy.

Andrew Roberts

Andrew Roberts

There is much more to the story of this giant, but perhaps this suffices to indicate what a reader will find. At the end Roberts concludes that Napoleon was indeed deserving of the title Great.

‘The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney’ (2007) by Michael Barrier

Walt Disney was born in a small railroad town in Missouri. It was a water stop for trains, and he retained a lifelong fascination with trains which led to Disneyland.

He was a bright and industrious young man who had seen too much farm work as a boy to want to be a farmer. In his desire to escape the physical drudgery of farming he is akin to Huey Long.

His distinction in the early animated cartoons was the effort to put emotion into the toons. Whereas rivals like ‘Tom & Jerry’ or ‘Felix the Cat’ were drawings whose heads exploded and then re-assembled, Disney started putting puzzled or hurt expressions on the face of Mickey Mouse.

Walt Disney never stood still. He went from one project to another. He was a workaholic and worked late into the night, even when he was the proprietor of Disney Studios, he was frequently alone in the Studios at midnight.

He was also an innovator and a demon for ever higher quality in drawing, animation, movement, colour, and more. Innovation and quality meant that animators wanted to work for him, and many left higher paying jobs to work at Disney Studios to learn more of the trade. One of his innovations was staff development, as we would call it today. The author also credits Disney with the concept of the storyboard, now used in every movies industry in the world.

He could be volatile. There are many claims that he was tyrant or a racist but this author finds no evidence for either claim. Though the swings of business meant that at times, loyal and able staff had to be dismissed because there was no money to pay them. He was categorically anti-union and paternalistic as an employer. He equated unions with communism as did too many others during the early days of the Cold War, and he was a friendly witness before HUAC. Yuk!

Despite the temptations of Hollywood he was ever loyal to his wife. The author implies that Disney broke profitable business relations with some actors and directors whom he thought, perhaps wrongly, did not treat her with respect. After their first child she had several miscarriages and that led them to adopt a second child.

His brother Roy ran the business side, but always deferred to Walt’s creativity. When Walt used company money to build a scale model train as a hobby, Roy did point out that the stockholders would not accept that. To justify the scale railroad it became a company project, and led to Disneyland.

Roy Disney

Roy Disney

Disney visited many amusement parks and found that those aimed at children bored adults and those aimed at adults bored children. In both cases the boredom meant a short visit. By combining amusements for both adults and children, the visits would be longer, and patrons would spend more money. To facilitate longer visits and more spending, Disney introduced suff development to train guides, operators, vendors in dealing with customers. Another Disney innovation is queue management.

I was surprised to learn how fragile the Disney empire was even in 1960s when it seemed to be an American institution second only to the White House. Since Walt was always pushing ahead to another project – more and better cartoons, television, movies, Disneyland, Disneyworld, EPCOT (which is not mentioned in this book), the finances were always stretched. One sign of this is that the brothers Walt and Roy lived modestly compared to the Hollywood standard of the time.

‘Snow White’ (1937) made mint and set a standard that he never equaled. The single-minded determination to make a feature length cartoon, and to make it an artistic and commercial success is one of the most interesting episodes in the book. The banal description of ‘Snow White’ on the InterNet Movie Database belies what a groundbreaking work it was in 1937.

Disney set out to top that with ‘Fanastia’ (1940) but the technical problems were so great that this project devoured money, and in the desperation to get a product and some financial return, it was neither an artistic nor commercial success. Disney did not always get it right.

Disney made the transition from cartoons to live action films thanks to World War II. When the war began the Department of Defense contracted Disney Studios to make training films, which were at first technical, involving a lot of diagrams and animation, but came to involve actors showing how to repair an engine, or repair a tank tread.

‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ (1954) and ‘Davy Crockett’ (1955) both made money and attracted acclaim. Genius as he might have been, Disney did not follow-up either successfully. He was always reluctant to hire expensive Hollywood directors and actors and ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ is the only time he did. When ‘Davy Crockett’ made even more money, he decided he did not need high priced talent. I do remember that cap!

He seems to have misunderstood the success of ‘Davy Crockett’ because he then cast its star Fess Parker in a series of duds. They were duds because, in effect, Parker was cast as a supporting actors to, by turns, a group of children, a dog, and a bear. When his contract came up for re-newal, Parker quit.

By the way, he picked Parker out of the film ‘The Thing’ (1951), and as an unknown, Parker came cheap.

The 1950s and 1960s television series of Disney was designed to promote Disneyland.

There was a lot of office politics in Disney Studios. Getting his attention was key but he had so many projects going, including constantly rebuilding and expanding the studio that his attention was scarce.

He travelled a lot in the States but also in Europe. The honours and awards poured in but he remained restless for the next project.

There is a good deal in the book about the technical aspects of animation. More than I expected in a ‘Life.’

MIchael Barrier

MIchael Barrier

Michael Barrier played Lieutenant De Salle in Star Trek, the Original Series episode ‘Memory Alpha.’

De Salle

De Salle

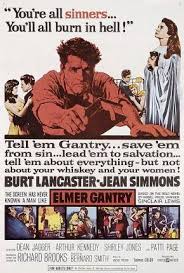

‘Elmer Gantry’ (1927) by Sinclair Lewis

In this novel Lewis recounts the life and adventures of the title character with the sledgehammer subtlety that marks all of his work that I have read: ‘Arrowsmith’ and ‘Babbitt.’ In a generous mood, I will call it satire rather than sophomoric caricature.

Elmer Gantry is a self-centred charlatan who starts out a travelling salesman selling anything and everything from snake oil to farm machinery to anyone with a dollar. He has a gift of the gab and personal charm that makes him a success, but he also has many faults that undermine that success, chiefly the faults of whiskey and women.

He learns to sell religion and salvation, and not only does that make money, but it also gives him a power that is so satisfying that, to some extent, he controls his faults. Indeed, he stops drinking altogether. Gantry enjoys the competitive element in drawing crowds and raising money against other rival churches and barnstorming evangelists. Most of all, he enjoys manipulating others, for which he seems to have a gift, i.e., people believe what he says, even those who should know better.

He uses and abuses believers, fellow preachers, and several women.

There are a few bon mots and a couple of well-turned phrases, but for three hundred pages the prose is, well, prosaic.

The telling is episodic and relentless in demonstrating Elmer’s one-dimensional unscrupulousness and complete amorality. There is no limit to Gantry’s mendacity, duplicity, and deceit. There is never a qualm of conscience. Never does he do something for another but always for Elmer over the forty year period covered in the book. He never seems to grow or to change. He switched addiction from booze to power, discovering he could still have women on the side. It becomes one note repeated again and again.

The only people who see through him are either bookish ineffectuals or the blackmailers, who are themselves so corrupt that they have to back off.

The underlying theme is that religious people are all fools in one way or another. Like those without religion, Sinclair cannot imagine what faith means to others.

There is one dramatic moment when Reverend Pengilly asks Elmer why he does not believe in God at the end of Chapter 27 and it not resolved and so becomes a non sequitur.

By far the most interesting character and the best part of the book concerns the strange evangelist Sharon Falconer. She is far more compelling than Gantry himself. She also seems to be sincere in her mission, though she likes the money, too. Doing well by doing good, as Ben Franklin did say. She seems to be a split personality. Lewis kills her off. That is approximately the middle third of the book.

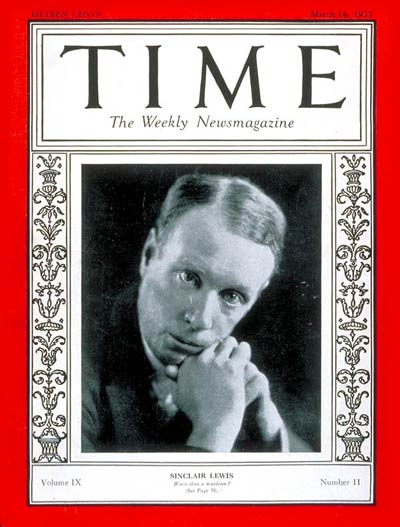

Sinclair Lewis on the cover of Time Magazine.

Sinclair Lewis on the cover of Time Magazine.

I retain a very strong recollection of the film ‘Elmer Gantry’ (1960), but had never read the book. In memory the film concentrates on Falconer. Time to do the homework. While travelling in Turkey, I downloaded it to the Kindle and read it.

A lobby poster for the film.

A lobby poster for the film.

When I started reading the description of Elmer at the beginning brought to mind the very actor who embodied him in the film, Burt Lancaster. It seemed as though, Lewis created Elmer cased on Burt, though that is chronologically impossible.

The mysteries and treasures of O’Connell Town. 2

The Bougainvillea is a beautful and deadly thing. Those that have been near one, know what I mean. Its name comes the French admiral who commanded the mission that lead to the first European description of this fecund, tropical beauty. We had one for a while, in a pot to contain its growth. Even so it grew over the door to the laundry, and one of us had to go. Either the Bougainvellea or all of us. Those thorns are large and small, each sharp. Owie!

These two are on Hordern Street in O’Connell Town at Shane’s house.

The colours are as intense and vibrant as the thorns are sharp and penetrating.

Beautiful to look at — from a safe distance.

The mysteries and treasures of O’Connell Town. 1

For the cognoscenti O’Connell Town is the historic name of an enclave within the larger historic Bligh Estate that once encompassed most of contemporary Camperdown, Annandale, and Newtown. There are no remnants of the Blight Estate left in the area, or so I have been told by a fellow gym user who has lived in O’Connell Town for forty years.

Having moved into this area, while dog walking, going to and from the gym, and to the station and bus stop we are learning about O’Connell Town.

We noticed this display on the corner a few days ago. Take a look.

Look closer. It is an album of photographs blue tacked to the outside of a house. See.

There were twenty photographs of assorted subjects.

Then one day, one was missing but the rest remained. My hands were full and I did not get a picture. Then a few days later they were all gone only leaving behind the blue tack.

Huh? What was that about? You can tell me.