In April 1962 William Faulkner spent a few days as a writer-in-residence at a college in a small town in New York state, West Point. The book combines the typescript of the story from ‘The Reivers’ which he read (including his hand-written emendations), and transcripts of several question and answer sessions with students and faculty.

It is overproof Faulkner and there is no stronger elixir. The moral purity of the man glows. By moral I mean his commitment to lift the hearts of readers with true accounts of the conflict within and between us. ‘Morality’ does not mean telling other people what to do; it means doing the best one can at what one does. Believe it, Faulkner says it better.

He acknowledged that his novels are uneven but he loves all his children, the crooked as well as the straight, as would a mother, and learns from them each. When asked about the parochial nature of his work, he admits it, and then goes on to the eternal themes of loss, love, onus, anger, belonging, challenge, and — most of all — comprehension. Asked to say which novel is his favorite, slowly he answered, as I knew he would, ‘The Sound and the Fury’ because it hurt so much to write it, and it still hurts ‘when I read a few pages of it.’ The implication is that a few pages at a time is all he can bear.

Why is the idiot Benjy the narrator in ‘The Sound and the Fury,’ he is asked? Is it because of his childlike simplicity? No, said Faulkner, though much more politely than that, it is because Benjy does not understand what he sees, and even so the novelist must try to make it understood.

Asked about Southern racism he replies that it is a terrible disease to be eradicated by education, but it won’t be as easy as eradicating polio. No, not the education of blacks to be like whites, but the education of whites to end racism. [Maybe in another thousand years.]

The students asked leading questions right out of the textbook, and he gently turned them aside to come back to the bedrock where there are no labels, no simple either/or answers, no symbols, nothing that can go on an exam paper, just the story. Any man’s story is, in part, every man’s story, someone once said.

Asked how he plans his novels he said this:

‘A disorderly writer like me is incapable of making plans and plots. He writes simply about people and the story begins with a phrase, an anecdote, or a gesture, and it goes from there and he tries to stop it as soon as he can. It’s not done with any plan or schedule of work. I write about man in his comic or tragic condition, in motion, to tell a story — give it some order and unity and coherence.

Or in reply to a question about the value of literature:

‘Poetry is best and first. The failed poet writes short stories. The failed short story writer has nothing left but the novel. Poetry condenses everything in a few lines, the short story in a few pages, the novel… goes on.

That old chestnut is tossed in, Where do you get your ideas from?

‘It starts with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does, and maybe even thinks, but he is in charge. I have little to do with it but edit it into some coherence to lay emphasis here and there, but the characters themselves, they do what they do, not me.

Leo Tolstoy said something like that in his time.

When I visited Rowanoak in Oxford Mississippi on stifling hot day one August I beheld his well-used typewriter and the walls on which he used to doodle with his characters. He did try to use the technique he had learned in Hollywood of storyboarding for some of his later novels.

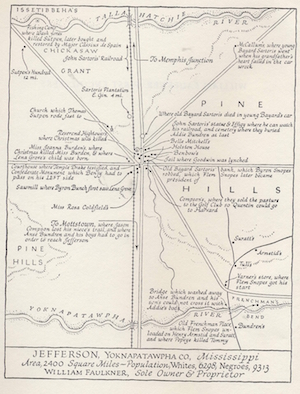

My nomination for his most powerful novel? That is easy: ‘Abalsom, Absalom.’ His most accessible novel for a newcomer who has yet to enter Yoknapatawpha County is ‘Intruder in the Dust’ and his long short story ‘The Bear.’ The funniest is ‘The Reivers.’ The most exhausting? ‘As I Lay Dying.’ The most compelling? ‘Light in August.’ The most harrowing? ‘Sanctuary.’ The most penetrating? ‘Go down, Moses.’ Each of his titles has something distinctive while they form a whole. And let’s not forget that very short story, ‘A Rose of Emily.’ I was always sure it was ‘Emily’ for Emily Dickinson.

A word of warning. Faulkner only became Faulkner in Yoknapatawpha Country.

His earlier novels like ‘Pylon,’ ‘Mosquito,’ and even the elegiac ‘Soldier’s Pay’ are pre-Faulkner. I do believe I have read them all (some more than once) and most of the stories, too, that he managed to stop short before they, too, grew into novels.

On that pilgrimage to Oxford I also recalled that it was on the campus of the University of Mississippi that there were race riots in 1962 led by the governor of that state and subdued by Federal troops. This was a time when Faulkner could not show his face on campus, where now he is honoured.

Category: Book Review

‘Victor Hugo’s Conversations with the Spirit World: Literary Genius’s Hidden Life’ by John Chambers. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1998.

Eggheads! Did Victor Hugo (1802-1885) wrote ‘The Miserables’ on Guernsey in the Channel Islands? Yes, he did! He spent nearly twenty years in exile, three years on Jersey and most of the remainder on Guernsey. While this book is not a biography it does limn the relevant elements of this gargantuan writer’s gargantuan life. His books were big and so was he, and as big as he was his ego was even bigger. He regarded himself as the greatest writer ever, full stop, period, and end. He did not mean the greatest French writer, though he meant that, but the greatest writer of all, including William Shakespeare, who latter confirmed this judgement! (The best French writer had to be the best, because French was the best language per Hugo, though he had no knowledge of any other languages. It was a priori knowledge.)

No he was not a Mormon but yes the long-dead Shakespeare did concede Hugo’s surpassing genius … in a séance, for he sampled, practiced, and studied spiritualism with the same intensity he did everything else. At first he was disinterested in the many varieties of spiritualism that washed around Europe in the middle of the Nineteenth Century, but tolerated his wife’s interest, and then himself became hooked when it seemed that he could communicate with his dead daughter, the first born whom he loved (almost as much as himself, as one wit had it).

Some may remember ‘Bergerac.’

Some may remember ‘Bergerac.’

It was a time when the line between the living and the dead was a veil to some. Magnetism, mesmerism, table talking, automatic writing, rap rap, these were all in vogue. Once Hugo tasted this activity he drank deeply of it. A séance might start at 8 pm with a dozen participants in his Guernsey house and as the others departed or fell sleep in place, he continued on and on into the small hours of the morning.

And why not, he was H U G O after all and the spirits of the long dead crowded around to meet him! To the dead, he was a celebrity. [Pause.] Thus did Shakespeare rap out a message as did Aeschylus, Molière, Niccolò Machiavelli, and the Emperor Napoleon. Ego, indeed. He found further confirmation of his own self-estimate in these exercises, as if the chorus of praise from his contemporaries was not enough. Gargantuan that ego.

A séance.

A séance.

Hugo was not a Christian and yet he prayed. Hugo was not a socialist and yet he spoke for the dispossessed. Hugo was not a monarchist and yet he supported Louis Napoleon. Hugo was not a democrat but he came to oppose Louis Napoleon. Hugo loved Paris and yet lived in exile in the Channel Islands. Hugo was principled and yet he broke his word more than once. Hugo despised politics but twice served in parliament. Hugo made a point of defying classification with any one side or position. The words of Walt Whitman came to mind: ‘Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contract myself, I am large, I contain multitudes’ (‘Leaves of Grass,’ 1855). Hugo was a multitude.

Statue Hugo on the island.

Statue Hugo on the island.

Among the spirits who paid court to Hugo was Niccolò Machiavelli during a séance 16 December 1853 and on two other, later occasions (p. 224), and that is why I had look at the book. Most of the séances were recorded by a scribe as the spirits spelled out their messages a letter at a time, mostly in French, sometimes in Latin, and occasionally in an incomprehensible mishmash. While several participants including Hugo himself wrote up the experiences using the transcripts, most of the original transcripts have joined the spirit world, i.e., they have been lost. In this book we find that Machiavelli visited Hugo twice, the first two times they talked politics, and the last the subject was reincarnation and a summary of that last conversation is presented. Nothing further is said about the political discussions because these are among the lost transcripts. Given the Hugo was proscribed by Louis Napoleon III it is likely that Hugo denounced tyranny to Machiavelli, ah hem, in the transcriptions that survive Hugo does a lot of the talking, and so he probably did with Machiavelli who was probably left to agree as most people, living or dead, were in conversation with Le Grand Victor.

John Chambers

John Chambers

The book is well written and based on Hugo’s own accounts and those of contemporaries and it reads like a novel with asides for exposition. However, I had no interest in the word-by-word translations of the actual channeled material in the sessions which form the bulk of the book.

Marc Bloch, ‘Strange Defeat” (1944)

This is a personal memoir of a French officer who was on the front line in Flanders in 1940 during The Defeat. He was a supply officer who managed fuel for tanks, ambulances, motorcycles, cars, and trucks with Henri Giraud’s First Army. Bloch was a professor of history at the Sorbonne, and he volunteered to serve in 1939 again, having been an infantry captain in World War I. Some may recognise the name for Bloch was also a remarkable historian whose two volume study, ‘Feudal Society,’ is one of the most compelling works of history I have read.

Bloch wrote ‘Strange Defeat’ as a diary in the last months of 1940, and it remained unpublished at his death in 1944. He was in the Resistance, arrested by the Gestapo, tortured for information, and then murdered. None of this figures in his pages but it is a grim reminder of the mortal gravity of the place and time.

Bloch muses on his own reactions to the approach of war and his decision, at age fifty-two, to take up arms again and reflects on the men with whom he served, and analyses the Defeat from his captain’s eye-view.

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

Professor Bloch of the Sorbonne

He emphasises that the military shibboleths of order and method could not bend but they could break. That is, there was little sense of urgency when the German attack began. He had fuel requisitions rejected because a corner of the page was torn or the ink had run, which meant a long drive back to complete a new copy and get it signed by field officers whose troops were engaged with the Germans, and then return along roads strafed by the Luftwaffe. None of these exigencies were sufficient to compromise protocol. There was all the time in the world, until time ran out and then panic set it.

Even when the First Army retreated, it did so at a leisurely pace, moving back twenty kilometres. His point is that the insistence on procedure and these short retreats were measured against trench warfare of World War I, not against the mobile warfare of the Panzers. A twenty-kilometres retreat was but less than an hour from the next tank attack, which was never enough time to re-set the line of defence. Yet French Army doctrine would not permit a longer retreat, and so nothing was available to facilitate it in the way of equipment, road signs, traffic controls, communication, identified positions, marked map coordinates, and expectation. (To retreat a longer distance required an order from Supreme Command and Supreme Command could only reached by courier and no courier could get through. Supreme Command refused radio and telephone communication even in distress.) The First Army then retreated in these bite-sized steps five or six times before it completely disintegrated. At each retreat more units lost contact, were cut-off by marauding Panzers, read the map sideways and wandered into a Belgian bog, or collapsed in exhaustion and fear.

Then there were the personal rivalries he saw in the career officers in the many headquarters where his duties took him. To say to one colonel that he had instruction from another colonel meant he would get no hearing at all, because these two colonels were old adversaries in the promotions list. After mentioning the first colonel’s name, Bloch watched helplessly as the second colonel dropped his requisition into a drawer and with an icy word dismissed him. Clearly that chit was going no further up the chain of command.

There are many other examples but perhaps enough has been said to make the point. The procedures were cumbersome, inviolable, mysterious, and most of all based on absolute obedience at the expense of any initiative. (By the way, German intelligence services were aware of French army procedures and took them into account in their own planning.)

Black was the day, but Bloch also met, worked with, and observed many officers who manfully did their duty despite the circumstances. More than one staff officer stayed at the radio or telephone directing retreating units to Dunkerque even as shell fire fell on them. Bloch is one of those thousands of men who spent days on the sands at Ostend as British troops were evacuated while the Luftwaffe strafed the beaches and artillery fire grew closer.

The miracle at Dunkirk

The miracle at Dunkirk

Along with more than 120,000+ other French soldiers he was himself evacuated. (Winston Churchill personally ordered the Royal Navy to make no distinction among Allied soldiers and to board them first-come, first-served. For a day or more before that order the Royal Navy had only taken Brits.)

Bloch landed in Dover, marched to the train station, stopping for tea and scones served to the group of French troops he was with at the local lawn bowls club, then onto a train to Plymouth where he boarded a ship for Bordeaux, and thirty-six hours later he was again in France. The French troops shipped back to French Atlantic ports like this were without weapons, some had lost clothing, particularly boots in the surf at Ostend-Dunkerque, some were wounded or injured, and devoid of any chain of command. Bloch and the compatriots he shipped with were billeted in a health camp near Bordeaux, where, he observes, they were received with far less warmth and civility than they had experienced in England where he and his fellows were heroes who had stemmed the tide of the Boches, but in Bordeaux they were burdensome failures.

In World War I the city of Bordeaux was a million kilometres from the front; not so in the mechanised age. No sooner did Bloch arrive than did the Germans. He became one of those poilus, dirty, dazed, ragged, head down, among a thousand others on a road, escorted by a lone Wehrmacht private with a single-shot carbine, marching into captivity.

Les poilus

Les poilus

At fifty-two the Germans deemed him too old for slave labour in the Reich and he was paroled to begin his career in the Resistance shortly thereafter.

A book to be read in parallel with ‘Flight to Arras’ from the pen of Antoine de Saint-Exupery, he of the ‘Little Prince.’ St.-Ex was an air force pilot who flew combat in 1940, then fled to Algeria to continue the war with the Free French. He, too, died in 1944 while on a mission.

Ernest May, ‘Strange Victory: Hitler’s Conquest of France, 1940’ (2000)

‘What experience and history teach is this: That people and governments never have learned anything from history or acted on principles learned from it.’ Thus spake George Hegel in the ‘Lectures on the Philosophy of History.’

In contrast Ernest May explains the German victory ‘in terms applicable beyond its character or epoch’ as a parable for other times and other places. We can learn from history is the burden of this phrase. We can but do we.

This tome sets out to qualify, refute, and set aside the three most common interpretations of the Fall of France. Instead the Allies’ major error was to misunderstand German intentions, both politically and militarily.

These are the three common explanations of the German defeat of France.

1.That the Germans had a crushing superiority of men and material.

2.That the French and British were badly led.

3.The French people were morally lax.

Of course, there is some truth in each, which is why they have taken root, but May’s claim is that they are not decisive either alone or in combination. The Defeat was not a sure-thing, but rather a long shot with such a high risks that only a singular mad man like Hitler would do it. ‘Singular’ is not the right word. What I mean is that he alone decided, while in the Western countries there were many hands at work.

Against (1) the French and British had better weapons, e.g., French tanks, and more airplanes in the RAF. In addition, there was that large and well-equipped French Army. The German generals were dubious that they could match the Allies, and said so repeatedly to each other and to Hitler.

Against (2) there were many excellent leaders in a situation that defied rationality, i.e., Hitler wanted war and that was a fact Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier could not perceive, themselves horrified at the prospect of another war. The most significant leadership failure is probably Belgium’s King Leopold’s vacillation and that of his government. Certainly May does not gloss over this one. He also acknowledges that French generals (1) did not switch from peace time budget politics, crying poor, to war time reality easily and that there were political rivalries among them that were more important to some than the fighting and (2) the leisurely way communications were done by courier rather than telephone and the many levels orders had to go through to be issued and obeyed. These latter points were structural, it is true, but they were designed and implemented by the very French generals who later complained of these cumbersome structures, e.g. Gamelin. As to the former, May admits that Daladier had little hold on either cabinet or parliament and that Paul Reynaud’s decision to replace Gamelin in the midst of the battle with the seventy year old Weygand who had to fly to France from Syria was bound to fail. But Reynaud had to show the public he was acting. Well did he? Or would a stronger leader have weathered that expectation?

Against (3) the French had developed a resolve to resist by the time the Polish crisis occurred. Indeed the political leadership sensed this swing in public sentiment and that is what caused both the French and the British governments to go to war on the assumption that the public would not tolerate another compromise. Maybe but it is also true that there thirteen political parties, each jockeying of position, in the French parliament and they had a professional interest in disagreeing.

That there were doubts, fears, worries, hesitations among German generals is well known. Is not that always the case? Even the most bellicose general, when D-Day dawns has doubts, hesitations, delusions. Think of George McClellan’s fantasies about the grey hosts over the hill. Of Bernard Montgomery’s endless demands for more until he outnumbered the rump of the Afrika Corps 15 : 1 and then he still waited. Think of General Hermann von François waiting too long to execute his part of Schlieffen Plan. Think of General James Longstreet waiting for hours before ordering Pickett’s Charge. No general can ever had enough to be absolutely sure at any level of command. That the German victory was against the odds may well be true, but the qualms of generals is not proof of that contention. May seems to be insensitive to this general tendency.

And surely part of that demand for ever more material and men before committing to battle is done with one-eye on history. If made to fight now, and I lose, it is the politicians who are responsible for pushing me into the fight ill-prepared. If made to fight right now, and win, it is because I overcame the odds. Victory has a thousand fathers and defeat is an orphan. Many reports, appraisals, estimates are written for history to exculpate the writer, or to wring more funding from the niggardly political masters or both. ‘History memos,’ cynics call them. May seems insensitive to this common occurrence.

The divisions among the French cannot be papered over, though the author argues that there were periods, most of them of two or three years, when there were different alignments. Yes, and no. Yes there were accommodations but no, because many of the differences were deeply etched into history, regionalism, ideology, and religion. I am not convinced that there were significant changes. The social divisions in France were many and ran deep, and they certainly did not make France strong and imposing in Hitler’s perception. May seems to treat these divisions too lightly and to conclude that by September 1939 they had disappeared.

One of the things I do get from this book is that Hitler rose above the details of the arguments, how many airplanes, what range of flight, the number of bombs, the rate of production, the thickness of armour plating, the training time of pilots, and thousands of other technical details about training and equipment of all arms, and concentrated his assessments of France and England on the willpower of the elites to resist, to fight. While German officials and officers would cry poor because of the myriad of technical details involved, Hitler set little store by these facts. After an hour presentation on some such aspect of preparation by a general, he would wave it away with hand and talk about setting a date, next week, for the assault, leaving some general in stunned silence. The German generals delayed and argued for ever later dates. If left to their own devices, they would have been still planning the Western offensive in 1960. For them, planning, like management today, was an end in itself.

Also themselves deeply involved with technical details, Allied generals supposed that at some point German generals would talk Hiller out of a Western offensive, since on all the data the combination of France and England had the advantage, the more so adding Belgium and the Netherlands. Though Hitler saw this combination of allies as a weakness instead of a strength because the consultations would slow things down, the differing procedures would lead to confusion, the many heads involved would disagree, and there would be language barriers. He was right in all of these. May is silent on the fundamentals of Allied cooperation.

Instead of a direct attack on France the Allies anticipated an attack on Netherlands to get airbases on the English Channel, and perhaps on Belgium to close the port of Antwerp. Hitler played to that assumption with the first attack there, which proved to be a diversion, but it took far too long for that to be realised. That is, the French along with the British Expeditionary Force moved into Belgium to meet this attack and then got cut off by the main offensive in the south.

Added to that mindset the myriad of false alarms from November 1939 to May 1940, and the author does a good job of showing just how many false alarms there were, and how heavily qualified each was, along the lines of an ‘immediate attack will occur tomorrow, maybe, possibly, or not.’ He compares these occurrences to the warnings about Pearl Harbor to good effect. Some of these false alarms may have been planted by the Germans to weary, distract, confuse the Allies. It worked.

That Hitler did not attack the West immediately after Poland was at the time proof to many that the Germans were afraid of the might of the French army and the British airforce and would not attack later. This became another article of faith that led to the belief that an attack on the Netherlands and Belgium was most likely.

Meeting Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier face-to-face at Munich sealed the deal. Hitler saw no fight in either. At Munich Daladier said nothing, literally nothing. He was completely worn down by the back-biting and conflict within the French parliament and was counting the days until he would be displaced. (On Daladier, see the superb 2009 novel ‘The Ghost of Munich’ by Georges-Marc Benamou.) Benito Mussolini dominated the proceedings speaking a German no one could understand, but eschewing translators. That fog and mist suited Hitler for whom the meeting served other purposes (showing his generals he was willing to negotiate though he was not, buying time for preparations, courting world opinion, keeping the Soviet Union guessing, more closely involving Italy in his machinations, misleading all those who took him at his word, and, finally, assessing his opponents), the details were unimportant since he had no intention of sticking to any agreement. Chamberlain understood no German, no French, and no Italian.

We have that film of Chamberlain’s return from Munich with peace for our time, because Chamberlain mobilised the news media, including the BBC to record it. He made a point of mobilising and directing the media, says our author, far more than had been done previously by either Stanley Baldwin or Ramsay McDonald.

For their part it took Chamberlain and Daladier, and those around them, a long time to realise that Hitler really did want war. Many of them had been in the trenches themselves and they all knew others who had been and who had been maimed or killed. They could not conceive that anyone wanted to repeat that. It was only when it became numbingly apparent with the invasion of Poland that Hitler would not stop that they realised there was no point in further delay. The passing of time would favour Germany, as it added new territories and capacities, growing confidence, and allies, and the passing of time would see the British and French populations grew more and more fearful and demoralised. All that is the standard HSC interpretation from my years as an HSC examiner.

The French penchant for detailed planning meant everything was complicated. Because everything had been anticipated and planned, when a French unit came under fire there were pages of protocols to govern responses, and one has the impression that some officers were furiously leafing through the manuals to find the right protocol rather than directing their men.

The Belgians oscillated between clinging to neutrality and so denying cooperation with the Allies, or seeking Allied protection. Accordingly the move into Belgium when it was finally made, was too slow. Belgium also played a role earlier in stopping the extension of Maginot Line along its border. Belgium relied heavily on its own mini-Maginot Line in the impregnable Fort Eben-Emael near Liege, which was partly built by German contractors who turned over all the blueprints to the Wehrmacht, which meant the fort was put out of action by fifty men in a few minutes.

Eben-Emale was carved into this cliff face and dominated a river valley. There were many gun ports and block houses that do not show in this contemporary picture.

Eben-Emale was carved into this cliff face and dominated a river valley. There were many gun ports and block houses that do not show in this contemporary picture.

In building Eben-Emael successive Belgian government had declared it to be the essence of Belgian defence when it capitulated after one day, the psychological blow was decisive.

The Allies’ major strategic mistake was the belief that the Ardennes Forest was impassable to a large army, especially one with tanks and trucks. Even the evidence of eye witnesses did not overcome this conviction. It was fact-proof. Nothing would convince a distant senior officer that tanks and trucks were pouring out of the Ardennes even as they were pouring out.

The Belgian Ardennes

The Belgian Ardennes

But once the shooting started, the crucial tactical difference was that the Germans combined air and ground forces which the French did not do that for strategic reasons, and which the British did not do it for political reasons. The French air doctrine prohibited use of aircraft as air artillery! The cannons do that, period. The only tactical role of aircraft is to defend their airfields. The only strategic role is to bomb cities, which was ruled out at the time, not wishing to provoke the Germans into retaliating. The RAF wanted to keep all its aircraft to defend the homeland when the time came and flying low into columns of German armour would certainly mean heavy losses. Ergo when there were terrific traffic jams with thousands of German tanks and trunks on narrow roads, they were not bombed. Ergo when the French armies were pounded by the Luftwaffe as the Germans advanced, they had no air support of their own.

Moreover, neither the French nor British concentrated armour or motor transport, as the German did. That steel tip of the German offensive was irresistible, even though one-on-one French tanks were superior in armour and cannon. While the Allied tanks outnumbered the German ones, they were dispersed, so in combat the French tanks were usually outnumbered five to one. The French tanks were distributed one or two to a regiment of infantry as mobile block houses. Yet on paper there were more French and English tanks than German ones.

The analysis of intelligence is a crucial point. The French intelligence services gathered information and delivered it but did not analyse or evaluate it. A rumour would be dutifully reported, but its source would not be evaluated. A fact – the movement of troops – would be reported but not placed in the context of the reports of other troop movements. No one was responsible for putting all the pieces of information together. The several intelligence services did not want the responsibility and the general staff would have resented it had it been done. Ten reports of German troop movements would be filed but no one was responsible for reading the file and adding it up to ten. Each report was a discrete fact. The contrast was the Germans who integrated intelligence findings and analysed them thoroughly so that they knew how the French Army gave orders (in such detail that quick obedience was unlikely) and how the British gave orders (with so many qualifications and exceptions that quick obedience was unlikely).

Finally, at a tactical level both the French and British demanded absolute obedience, whereas the Wehrmacht doctrine stressed initiative and flexibility at the lowest levels of command, i.e., sergeants. In the confused situation that developed many a French command waited for orders that never came instead of acting independently.

One of the important points May offers is that most leaders (and their advisors) think the past predicts the future. To know what will happen tomorrow, look at yesterday. It does not always work that way. The linear projection of today on tomorrow can mislead as much as inform, if crucial information is ignored or changes are not perceived. Today is the best predictor of tomorrow, but only because nothing else is better, not because it is perfect. The hardest thing to do is to be open-minded about changes.

The many false alarms of a German attack on the West from October 1939 to May 1940 allowed German intelligence to monitor Allied reaction, and that fed back into the subsequent planning so that Fall Gelb evolved to the feint into the Netherlands and eastern Belgium to draw the most well trained and well equipped French armies along with the British Expeditionary Force into Belgium which would then be cut-off by the main attack through the Ardennes toward the sea and not toward Paris (which the French expected in a variation on the Schlieffen Plan of 1914). That the German attack on the Netherlands did not use tanks was attributed to the terrain, and not that the Germans were moving the tanks elsewhere to attack France, although there were many individual intelligence reports of such movements. The British feared German airbases in the Netherlands and wanted to respond with the drive into Belgium.

There were two political outcomes of the Fall of France.

First, Hitler believed his own genius was proven infallible and so did many of his generals, and those that did not, could no longer say so since Hitler had been vindicated by the achievement of a victory over mighty France. This combination of Hitler’s hubris and the generals’ reticence led to the gratuitous declaration of war against the United States and then the invasion of the Soviet Union and these led to downfall.

Second, the catastrophe frightened Britain into accepting the authority of government without the usual party and parliamentary bickering, back-biting, and undermining. It also put Winston Churchill into the big chair, and gave him a relatively free hand to select a cabinet, a war cabinet, and to appoint generals and admirals.

May argues that in the period from October 1939 to May 1940 French, and British, too, political leaders took positions and selected evidence to support them without regard to any overall appreciation of the realities. In both cases there was a reluctance to reveal one’s reasoning since that could then be challenged. Instead one just declared something to be the case, e.g., Swedish iron ore is decisive and if we can deny that to Germany the war is won. Rather than opening the subject up for debate to test its strength, it is closed. In the poisonous atmosphere of French politics exposing one’s reasoning would be have a suicide note and May does not credit that toxic atmosphere sufficiently.

Ernest May

Ernest May

The book is based on much original research and the results is a five-hundred page text with another hundred pages of notes and bibliography. The book takes its title from Marc Bloch’s moving little memoir ‘Strange Defeat’ (1944). On that more later.

‘The Wars of Spanish American Independence, 1809-1829’ (2013) by John Fletcher

Reading a biography of Símon Bolívar left me confused about events in Spanish America, and when Amazon’s Mechanical Turk recommended this title, I had a look and liked what I saw and sucked it down into the Kindle. Well worth the $1.12 price. This is a short guide book (just under 100 pages) that summaries the sprawling history of these rebellions, revolutions, and wars, the factions and forces involved, and the geography. The print version has coloured maps and graphics that do not show well on the Kindle but on the iPad they were superb.

Terminology first, I am tempted by habit to refer to Latin America but Fletcher makes it obvious even to the geographically challenged that Spanish America in 1809 extended to Oregon, including all the eventual United States states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and parts of others, as well as Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, St Domingo, and everything south to Tierra del Fuego with the exception of Brazil.

Second, it turns out I knew a little more than I thought, since I had watched Guy Williams (Zorro) fight the corrupt and incompetent Royalist regime in Old California while I was coming of age on the Rio Platte. Though Don Diego de la Vega is pretty vague about dates, it still turns on themes relevant to the 1809-1829 period. a distant colonial master, local villains, indians and blacks with no love for the regime. Locally-born Spanish Europeans taxed and abused by Spanish officials who steal all they can before returning to Iberia.

Third, I appreciated Fletcher’s deft summaries of the shifting divisions and alliances among both the Patriots and Royalists. Even those names are inadequate, but some labels are necessary. A score card is necessary to tell all the players, and at times they change uniform numbers, necessitating a revised score card. More on that below.

Among the American population were the three races and various combinations of them: Spanish, Indians, and blacks. When the shooting started the Spanish had been living in the Americas for nearly three hundred years. They were set in their ways. The Roman Catholic Church was a major factor. The Inquisition was hard at work in the New World.

Haiti loomed large in the minds of all Spanish, as it did in the southern United States into the 1860s. The slave revolt there confirmed the worse nightmare of many while confounding stereotypes. The blacks massacred their owners went the story, and took over, defeating two Napoleonic armies sent to teach them to respect the white man. Black slaves defeated two European armies!

There were divisions among the Royalists. Some wanted to continue the monarchy, but who was king, the old king clinging on, his usurping son, or Napoleon’s puppet. Moreover, some Royalists advocated a constitutional monarch and spoke less of a king and more of a constitution. In addition, in metropolitan Spain there were those who wanted no king of any kind, but did want to retain the empire. Each of these slivers of opinion was reflected in the Americas.

Among the Patriots were a host of differences as well. They called themselves ‘Patriots’ who were fighting for the freedom of their countries, and sometimes for their peoples, too. But which people? White, red, black, and the shades among them? The whites were further divided into those born in America, called Creoles, and those who moved there from the Old Country. Most of the blacks were slaves, but not all. The reds had tribal loyalties. Because of the methods of Spanish colonalism, the many colonies had almost nothing to do with each other. Lima was as foreign to Caracas as Madrid.

Most of the Patriots were loyal to their province with no larger conception of Spanish America. As soon as the Royalist were driven out the provinces would fall into conflict over rivers, boundaries, mines, and symbols. Sometimes they did not wait for the Royalists to be driven out before starting a war among themselves. A Columbian army would not go to Venezuela to fight the Royalists, nor would a Venezuelan one go to Columbia. And so on and on. If there is strength in unity this was one strength they did not have. Bolívar argued that if the Spanish retained one toehold in the Americas, then one day they would reassert their claims to the colonies.

Bolívar and José San Martin were among the few who saw a larger picture, the former for political purposes and the latter for military purposes. Though Bolívar had a political goal of a united Spanish American, he was not the accomplished soldier that San Martin was, but San Martin lacked Bolivar’s vision. Nor was there much chance they could work together. Bolívar was brassy, impetuous, egotistical, as well as determined, dogged, and tireless, while in contrast San Martin was reticent, careful, self-effacing, methodical, and slow (because it takes time to think), as well as a professional solider who was a strategist of note and a tactician of creativity.

Certainly a quarter, perhaps a half, of the populations (red, white, and black) in Spanish America died in this period. Many were killed after the battles, and others died of diseases loosened by the upheavals of warfare. Though Spain was feeble, on one occasion it managed to dispatch an army of 40,000 to the Americas to end the rebellions. Whole cities were murdered after battles to eradicate the enemy.

To get soldiers both sides courted the red and black races. The Spanish approach was to offer material reward, while the Patriots offered emancipation. The material reward of money would allow a slave to buy his freedom. The Royalists did recruit some individuals this way. Bolívar in contrast would declare emancipation and then recruit blacks to fight to retain this new freedom. The worked, too, on a larger scale. As a result slavery was outlawed a generation or two earlier there than in the United States. A parallel approach was taken by each side to recruiting indians. The Spanish offered individual incentives, Bolívar emancipation from forced labor and the so-called red taxes. Likewise the Patriots recruited soldiers from the captured Royalists with promises of citizenship.

In between the Royalists and Patriots were self-serving bands of armed men that preyed on both Patriots and Royalists or made temporary alliances with either to secure booty. More fearful than any of these bandits was the pestilence and disease let loose by the destruction of waterways, wells, damns, and the like.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars meant the world was awash with war surplus, and much of it went to these conflicts from northern California to southern Chilé. Likewise, there were demobilised soldiers who had no other life and who became mercenaries on one side or the other. Men who had fought each other at Waterloo ended up comrades in the European formations of San Martin’s army. Irish Catholics driven out of Ireland by Protestant England, found their way to Spanish America to serve with English veterans of Waterloo.

Brazil and Portugal also played roles in this story, trying to take advantage of the disruption among the Spanish to settle old grievances, appropriate land, secure river access, and the like. There were armed clashes between Brazilian forces and Patriots, Portuguese and Royalists, Brazilian and Royalists, Brazilian and Portuguese, and so on. All combinations.

No sooner had the Spanish given-up and left than the Patriots fell into prolonged conflict among themselves within cities and provinces and between provinces that became countries, some of the conflicts lasted until the 1860s. That goes some way to explaining the prominent role of the army in many Spanish American states. In contrast George Washington’s Continental army was under arms for eight years, but some of these Spanish American armies were at it for fifty years, e.g., in Argentina. Just as the Prussian army made Prussia, some of these armies could claim to have made the state.

As to the book, the organisation is coherent, the prose is crisp, and the pages are free from typos.

Fletcher is a UNL graduate and now a band manager.

‘Jeremy Bentham on Spanish America’ (1980) by Miriam Williford

Reading about John Stuart Mill brought to mind Mr Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), and I remembered that I had acquired a copy of this book years ago as relevant to utopia, though many might suggest one criterion of utopia would be the absence of insufferable bores like JB, as he referred to himself. While not a biography, the book does convey much of Bentham’s personality and habits.

The subtitle explains the remit of the monograph, ‘An Account of his Letters and Proposals for the New World.’

JB proselytised far and wide in England. He started out in law but when his parents’ deaths left him well off he became a full-time know-it-all. He wrote one tract after another, many are legal in orientation, and sent them off to one and all to influence opinion and incite action. He eschewed running for parliament on the ground that the duties thereof would distract from his broader and deeper influence. He ranged over many subject and topics, ignorance being no bar. Altogether a public intellectual!

Then he hit on the idea of the panopticon and devoted himself nearly exclusively to that for years, and sunk a lot of his own money into it. It started out as a model prison but as he honed the idea it became a more general social model. It is all in the name ‘pan’ = ‘all’ and ‘opticon’ = ‘seeing.’ All-seeing, a building made of glass so that everyone could see what each person is doing at all times. Little Brothers and Sisters are always watching! The social discipline born of this exposure would put us all on our best behaviour all the time. Michel Foucault has some things to say about this that are worth reading.

Disaffected by the failure of the Great British to embrace his panopticon, JB turned his gaze to the wider world, and there he saw Spanish America. This was a greenfield site in his mind. New societies were aborning there, and if they started off on the right foot, they would grow into perfect little Benthamic societies. He would be only too glad to tell them about that right foot.

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

Cue, another prodigious letter-writing campaign, and more tracts. Since he paid for the publication of his tracts they were not edited, and seldom reviewed. That may explain why most of them are so excruciating bad. Neither self-criticism nor second-thoughts featured in his personality. His contemporaries can be grateful that for every tract published he wrote two others that had to await posthumous publication in his collected works now safely confined to research library shelves for the terms of their natural lives.

The circumstances were a bit tricky, as reality can be. While Spain still claimed and asserted suzerainty over Spanish America, and these claims and assertions were largely respected by European powers, the Spanish Americans were rebelling against rule from Spain, imposed locally by appointees whose main goal was to enrich themselves with the least possible effort. San Martín, Símon Bolívar, and others were in revolt. These niceties did not bother JB, he wrote to Madrid, to Spanish colonial governors, and to the rebels offering his services as a lawgiver. Solon, reborn! Have laws, will travel.

In doing so he promoted his own considerable expertise as evinced by his numerous tracts, which he usually enclosed with his letters, and he cited testimonials from heads of states (who had never heard of him), savants (who regarded him as a crackpot), and religious leaders (who rejected him as an atheist).

Never one to stand on ceremony, while he was wooing the Madrid government to let him dictate to its restive colonies, he managed to find time to offer 400 pages of criticisms of the Madrid government, its constitution, its acts…. What a pompous prat, one might think.

More seriously, he suggested that his complete ignorance of local circumstances, and existing manners and morēs (or knowledge of Spanish) ideally suited him for the job, leaving him dispassionate, detached, unfettered, and rational. In short, he claims some of the qualities that Plato ascribed to Philosopher-Kings, though he never cites Plato, or anyone else for that matter. It is JB all the way, unalloyed.

He did make plans to travel to Mexico at one time, and then at another Venezuela but neither eventuated. Nonetheless, he continued his barrage of letters and tracts.

Imagine now a besieged Spanish governor in Peru with insurgents at the door, nearly all communication to the interior cut by Indians, receiving a letter…from Bentham running to 25 pages about whether the legal code should be written in italics or not. Bentham often seized on such trivial details and spent pages and pages on them, while the castle burned down. He had neither practical sense nor political nous. Though, surprisingly enough, some of his correspondents did take him seriously like Símon Bolívar, giving me cause to doubt SB’s wisdom. (Maybe I should read a biography of SB.)

Williford charts all this deadpan, resisting all but a few asides on the evident megalomania. This is an excellent, short monograph that shows a considerable volume of research, effectively marshalled to say what needs to be said with little fuss. Perhaps it started as PhD but if so the published version escaped the PhD-to-book syndrome – overkill.

I could not find a picture of the author.

I confess that I have a marked up copy of Bentham’s ‘Fragment on Government’ which I had to read in a graduate seminar, and I cannot remember one thing about it, except the relief at never having to look at it again.

In pursuit of John Stuart Mill I have also recently read Eric Stokes, ‘The English Utilitarians and India’ (1989) which I chose not to review, finding it so densely detailed that only a specialist in British colonialism in India could fathom it. I certainly could not, though I found informative the distinctions Stokes made among the Whig, Liberal, and Utilitarian approach to India. For the Whigs government itself is the enemy. For the Liberals education solves all problems when mixed with time. For Utilitarians there is no substitute for telling people what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and, if time permits, why to do it.

By the way, when Bentham’s parents’ estate was divided between the two sons, his brother took his half of the dosh and moved to the south of France to pursue the life of a sybarite. Who can say which was the greater service to later generations?

‘The Tin Flute’ (1945) by Gabrielle Roy (1909-1983).

A novel of life among destitute Canadiens in Montréal of the Great Depression. Yet a book that brims with life, and ends with optimism.

The description of the snow driven before the wind as a dancer pursued by a cracking whip was marvellous, graphic, exciting, and accurate. Then there was the house party and the young and inexperienced Florentine measures herself against her rivals, parents, and beau. Her combination of defensive quips and throbbing hormones is certainly right. Emanuel’s unwilling love for Florentine and her gradual response, each with inner doubts, provides the unity of the story.

Gabrielle Roy is the novelist of a Montréal now gone, the Montréal of Maurice Duplessis, and even the egregious Jean Drapeau, long before Le révolution tranquil. The working class French of 1940 stay of their side of Rue St Laurence in a quietude that is born with a stubborn resignation. The Church offers spiritual comfort in a world where there are few material comforts after a decade of the Great Depression.

That endurance is personified in Rose-Anna Lacasse, the mother of a starving clan of ten, soon to be eleven, children with her earnest but eight-year unemployed husband Azarius. All of them go to bed hungry and get up hungry. The children dress in rags and share shoes. Yet they all persevere.

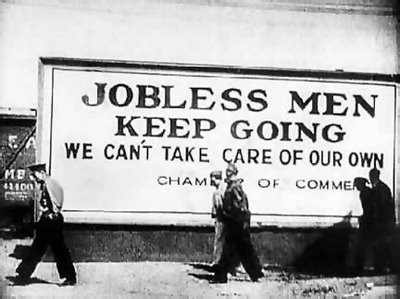

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

Roy enters into the lives of her characters, or maybe it is the other way around, they have entered into her life and she chronicles their determination, dignity, forbearance, and humiliations in a world they did not make, but in which theirs is to make the best of if that they can. The inner monologues of her cast of characters are compelling. Confused, determined, troubled, hesitant, defeated, defiant they may be inside, but outside each tries to maintain a façade. Rose-Anna is calm; Azarius is cheerful; Emanuel is self-contained; Florentine is scornful….

To a politically-minded person they are victims of an oppressive social order that could be changed. To Roy they are God’s children, each one precious, individual, and whole just as they are.

The novel, written by a Manitoba school teacher, provides a companion piece to The Canadian novel, ‘The Two Solitudes’ written at nearly the same time by a Nova Scotia school teacher. But the books differ. McLennan’s ‘Two Solitudes’ implies a political agenda and it looks to a changed and perhaps better future. Roy accepts eternal reality as the mystery of life in which we must trust in God and ourselves. That might sound passé, even retrograde, to some but in her hands it is a message of salvation.

By the way, in McLennan’s novel conscription into the Canadian army is feared by Canadiens, but in Roy’s novel three of the central Québecois characters voluntarily enlist, and a fourth throws himself into a war industry. The army represents a job, an income, after nearly a decade without either. (Yes, I know some of them ended their lives at Dièppe in 1942.)

Moreover, when I compare this book to so many contemporary prize-wining novels that I try, and fail, to read, I realise she has the one essential of a novelist, that so many published novelists lack, a story to tell about people. To which she adds a sympathy, an empathy for others that transcends the facile judgements that reviewers love.

I have read her ‘Alexandre Chenevert’ (1951) and ‘Where Nests the Waterhen’ (1955) and found much pleasure and occasion to reflect in each. There is a very informative biography of her on the Canadian Dictionary of Biography online web site. She wrote constantly and kept every word she wrote including letters sent (and received). The Amazon Canada web site has shown her for more than a year as ‘Roy Gabrielle,’ despite many complaints, mine among them. The Mechanical Turk has fallen asleep, it seems. I see in this mixup the fate of those with two first names, but others find a darker purpose to capture her work for the masculine!

Gabrielle Roy

Gabrielle Roy

The original title was ‘Bonheur d’occasion’ which is an idiom meaning, at its most basic, ‘Best wishes.’ The title ‘The Tin Flute’ refers to one incident in the novel. It was filmed in 1983, turning this compassionate study of grace under pressure into melodramatic drivel suitable for a mid-day movie.

‘A reformer of the world’

Reading Nicholas Capaldi’s biography of John Stuart Mill put me in mind of Mill’s ‘Autobiography’ and I found I had it on Audible already, so the rest was easy, well not quite. See below for some comments on using the Audible app.

Although his voice was a clarion for social equality and personal responsibility, generations of students have since been taught to despise John Stuart Mill as a progenitor of evil liberalism.

Sounds odd I know, but since the 1960s jaded intellectuals have made careers biting the hand – liberalism – that feeds them, having insufficient imagination to do anything creative themselves. When these pygmies are long gone, John Stuart Mill’s books will still be read; that will be the judgement of history. It is little wonder that the feeding hand has gradually lost enthusiasm for subsidising intellectuals.

Mill started to write the ‘Autobiography’ when he had a nervous breakdown early in life and then went back to it later. In addition, Harriet Taylor had a hand in editing it. Many PhDs have been earned trying to figure out when Mill wrote portions of it, and what Taylor took out or put in. The Audible version I listened spared me this Pin-HeadeD detail.

The early chapters are a description of the childhood of this prodigy with an emphasis on his father’s method of educating him. It is exhausting to listen to the account, the more so knowing, as he must surely have himself known in retrospect, that most of it was meaningless. Prodigious, yes, but neither lasting or meaningful. He may have read in Greek Plato’s ‘Apology’ at five years of age, but he did not understand it. So, too, with much else in this force-fed education, which was all work and no play everyday for years on end.

James Mill

James Mill

One unintended consequence of this gruelling education was that Mill was THE hyper-nerd. He grew up in a hot house that he seldom left until he was a late teenager when he went out of the house to go to work at the East India Company where he toiled for his father.

East India House

East India House

He was in his father’s shadow for much of his life everyday, socially, intellectually, and morally. It is painfully apparent to an auditor of the ‘Autobiography’ that Mill had no friends. He had peers; he had colleagues; he had associates; he had debaters and opponents. But he had no friends, which he as much as says more than once, though he uses the term ‘friend,’ it usually means someone he knew, and nothing more intimate. He had no interests but the unforgiving logical analysis of important matters learned from and constantly reinforced by his father. This is not the person to sit next to at dinner. He could debate the great issues of the day but he could not make small talk, or show any interest in pictures of a seat-mate’s children. A cold fish, I would guess. Ready to beat you to death in argument and inept in passing the butter, because he never played any boyhood games meant he had zero physical dexterity, something he himself notes twice in the ‘Autobiography.’

Chapter Five (5) is superb. In it Mill reflects on his many and varied experiences, and knocks off some bon mots as only he could. He paraphrases Thomas Hobbes’s remark that ‘When reason is against a man, he retaliates by being against reason’ which made me think of all those deniers (climate change, Catholic Church pedophilia, Holocaust, Greek debt, etc.). I listened to this while walking the dog, pushing pedals at the gym, or taking the train, so I could not take notes or mark-up the text.

HIs conclusion in this chapter is that political theory is best confined to a few principles which would allow inferences to be drawn in particular circumstances, rather than trying to lay down a single ideal institutions. Mill lost faith in a singularly unified theory and recognised the inescapable influence of context. Under the influence of Alexis de Tocqueville, Mill wanted the deductions to be based on facts, hence I referred above to inferences and not deductions.

Likewise, Mill concluded that perfect political institutions were of no value in themselves. The underlying social order was decisive. The most perfect political institutions would be hollow shells unless the society valued and embraced them for their purposes. To make a comparison, the church may be full, but do they really believe and act like Christians everyday in every way?

Mill once fancied himself ‘a reformer of the world,’ but during his depression, he asked himself this question: If all the material and moral ideals he espoused were realised in the world, would he then be happy? No, he answered. He concluded that happiness if not an end in itself, but rather a by-product of purposeful activity. Both trip and arrival are important.

In Chapter Six (6) Mill refers to Mr. Warren and the villages he set up. It was a passing reference but I want to see it in the printed text when the copy I ordered arrives. I found a reference to Warren and his villages in a history of anarchism. Mill’s praise for Warren villages is odd, since Mill knew nothing about them, not even if they existed. So much for Tocqueville’s influence.

Later in Chapter Seven (7) he refers to the Hare-Clarke voting system as the salvation of representative government over several pages. I have passed these passages on to Anthony Green. Likewise there is also in this chapter a reference to multiple votes for the educated, rather than the propertied, and I must get that and send it to Glyn Davis who once asked me about my comment, somewhere, on Mill and multiple votes. In the ‘Autobiography’ Mill says he proposed multiple votes in a submission; I have since tracked it down and will pass it on in due course.

There are some odd things about the ‘Autobiography’ to be sure. Mill never mentions his mother though there are many, many references to his father who died when Mill was thirty (30). It would seem his father had those nine (9) children all by himself. James Mill was a formidable fellow but he was no hermaphrodite. While there are only a few early references to Mill’s work for the East India Company. Yet Mill specialists have some strange stories about his habits at work.

This review affords an opportunity to correct some errors I made in the review of Capaldi’s biography. It was not Bentham that introduced Mill to poetry. Several peers led him to poetry. I also said he was called a Mechanical Man, not quite, but rather a Manufactured Man by some who found the analytical engine of his mind artificial and inhuman.

I found this Audible reading to be unsympathetic. It sounded almost mechanical, phrases of equal length and inflection followed one another without regard to the content. Perhaps that is partly a fault of Mill’s writing style, which is replete with dependent, relative, and embedded clauses with asides and comparisons which makes it precise but it does not flow.

Not quite easy I said, because Audible kept dropping out, asking me to log in again, resetting the book mark, and so on. None of that is easy when using the iPhone while dog walking. No doubt I brought this on myself, somehow. But it was annoying, and a lesser man might have quit.

‘Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot’ (1998) by Harlow Unger

Noah Webster (1758-1843) has shadowed me through life. In reading rooms, office desks, library shelves, legal offices, conference halls, spell-checkers, and seminar rooms, wherever I have gone there I found a direct line back to him on the spine of dictionaries. This Webster is that Webster, the dictionary man.

How and why he became that is a story I could no longer deny myself. He grew up in western Connecticut when it was the frontier. He was the bookish middle son. The family decided to see to his education, while the other children stayed and worked the farm. Off he went to a common (public) school where the emphasis was on discipline (secured by rod and whip). Not even the brutality he found there could quench the intellect within and at sixteen he entered the local church school, Yale.

At the time church and state were united in a Tea Party dreamworld. Taxes were paid at the local church which doubled as town hall and government offices. Yale was little more than a Calvinist secondary school for parsons, and it was funded by those taxes paid at churches. There was no religious toleration. Those who were not Congregationalists were, however, free to move west.

The taxes Great Britain imposed on the thirteen American colonies to pay for the expense of defending them in the French and Indian War of 1754-1763 were punitive, and precipitated the Revolutionary War 1775-1783 (in which the colonist reputiated their sovereign debt to England). Webster’s father had been a militiaman in the French war and during the Revolutionary War, Noah Webster joined a student brigade which marched around but found no English redcoats. However, the Revolution fired him with patriotism for the new world in the making.

He took up teaching children to read upon leaving Yale, and apprenticed to a lawyer for a career in law. That changed when in late 1783 his travel to a cousin’s wedding took him through an encampment of the recently victorious Continental Army of the United States. He, youthful idealist, was thrilled to see and meet the men who had created this New Jerusalem.

What he found was Babel. The men were at odds with each other over scarce provisions, ragged clothing, three-years of back-pay eroded discipline, and — what was worse — was the cacophony of languages. He heard Swedish from the men of Delaware, German from Pennsylvania, Dutch from New York, Welsh from Maryland, Irish from Massachusetts men, Scots from others, French from the forest men of Maine, Spanish from a few from the Caribbean, Italian was also to be found. All of these were further divided into dialects. If anything, English was just one of the plurality of languages.

The language barriers within Americans made prospects for productive cooperation unlikely, and it soon became his lifelong ambition to unite the States with an American language. He formed this ambition at twenty years of age, and stuck to it. The result is on the shelf, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary. (‘Merriam’ because when he died the brothers Merriam, long-time friends, neighbours, and admirers of Noah, bought the copyright from Noah’s widow, as a way of insuring her financial security. Part of that agreement was keep the name ‘Webster’ on it.)

My copy.

My copy.

The division, conflict, unproductive confrontations that he saw in the army camp were mirrored and enlarged among the victorious colonies which were held together by the so-called Articles of Confederation (1776-1789) which had only a congress meeting briefly twice a year. Each state was a law and nation unto itself. Pennsylvania and seven other states had a state army. At the borders of each state tariffs were levied. Since the British had not surveyed more than one hundred miles inland in most places, there were disputes about western borders that were settled by the gun. Each state issued its own coins and bank notes, ran a postal service of sorts. Some levied visa charges for visitors from other states. A murderer could flee across a state border and most likely escape pursuit or apprehension. I said fourteen states, and not thirteen, because Vermont seceded from New Hampshire.

For Webster to secure copyright for his first book meant that fourteen state legislatures had to enact copyright legislation and he then had to secure fourteen separate warrants, each with slightly different conditions. In this state of confusion, there were those who thought returning to British suzerainty would be preferable. Some of these were diehard Tories and others just wanted order and stability.

All of this division stimulated Webster to redouble his efforts. H travelled to nearly every state capitol, selling his book as he went, and lobbied first for a copyright law and then to secure copyright for his book(s). Doing so was hard, expensive, and took him away from home for months at a time. It also made him a national figure, with personal friends in every state.

He was innovator in every respect, As a teacher he thought school was to teach children to read and write, not simply to beat them into submission. He pitched his lessons at the level and world of his five and six year olds, striving to make learning fun, interesting, relevant, and easy. He was very successful at it. He set up his own school and parents who wanted their children, both girls and boys, to learn subscribed to it. He prepared his own teaching material and these became the three books: The Speller, The Grammar, and The Reader. Each was American in each and every way.

To make spelling easy and fun he simplified it, by dropping silent letters, like ‘u’ in most occurrence of ‘ou’ or the unpronounced double ‘l’ in traveller or the double ‘g’ in waggoner, and matching sound to letter by using the ‘z’ extensively. He dropped many, many other silent letters, so that ‘give’ became ‘giv’ and the same for all words with an unsounded terminal ‘e.’ He also tried to change existing spelling to match sound so that some instances of the letter ‘c’ became ‘s’ or ‘sh’ which certainly have made English easier to learn. English, in part because of its polyglot origins, has many silent letters and varieties of letter sound values. And he thought American English had to be learned, and it would be better for being distinct from British English and for being rational in the spirit of the Enlightenment. He was an admiring reader of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, Adam Smith, and their ilk.

He likewise inventive in grammar, dropping the Latin cases which had theretofore been used to teach English grammar. Reader, when was the last time the ablative was necessary?

The reader, aimed at young children, was entirely home grown. Gone were incomprehensible British essays about the Astronomer Royal, or legal disquisitions on the Welsh marches, and in came essays about the New England forests, thanksgiving with the native indians, and paeans of praise for the stalwarts of the Revolution. He made an exception for the poetry of William Wordsworth.

No publisher would touch his work. It was too novel, untried, and untested. He borrowed from his family and paid for the first edition of The Speller himself. Five hundred were printed, and by the end of the year 5,000 had been sold. He set the price low to make it accessible and he invested the income in The Grammar, and so it went. Throughout his life he made enough money to live and support his family, but nothing more.

He was a publisher’s dream author. He travelled the country for weeks and months at a time, selling the books in person to every churchmen, legislator, lawyer, judge, and school teacher he could find. During this period he also found time to argue for a stronger national government and that won him friends among the emerging Federalists (and enemies among others). Indeed in the Constitution of 1789 some of his ideas were embodied, and others he proposed were deleted. Chief among those embodied was a strong central executive, the President, and among those rejected were universal manhood suffrage, female equality, and emancipation the slaves.

Noah Webster.

Noah Webster.

Much of the middle of the book is a summary of American history in the turbulent period from 1789 to 1830. Reading it reminded me of how well educated I had been, there along the Platte, because I knew most of it in broad: Citizen Genet, the undeclared naval war with France, the Jay Treaty, Thomas Jefferson’s ascendence, and so on. Webster was constantly in the fray, opinionated, pompous, self-righteous, and often right. He saw unity as the only path to survival, and advocated a strong central government.

He moved to New York City to found first a magazine and then a newspaper, both of which failed at personal and professional expense. He then revised his school books and went on the road to sell them. Finally at about 40 he sold the rights to his books, rather than face another round of travel, and started on the dictionary that made him immortal. He also worked with his cousin Daniel Webster (he of the devil in the Ambrose Bierce story) to enact the first copyright legislation in the United States.

He worked on the dictionary singlehanded for 20+ years and compiled 70,000 entries, far in excess of its only rival, Dr Johnson’s (which I am proud to say adorns our shelves). To study the etymology of words Webster learned German, to go with the French and Latin he had. In time he traced words through dozens of languages. He travelled to London and Paris when he was 60 to research in libraries there. It was a Herculean labour. The result was pure Noah Webster. Definitions, examples, the etymology was slanted to reflect his Calvinism, American patriotism, and Anglo-Saxon heritage.

It was difficult to find a way to publish this whopper. He did finally manage to do so with financial support from John Jay (of the Federalist Papers), and it was an immediate commercial and critical success. He had long since modified his efforts to reform spelling on rational grounds and moderate his zeal for being a know-it-all. The two volume work that resulted was hailed far and wide.

Since the veneration for Dr. Johnson and his dictionary had prevented any new dictionary in England for two generations, Webster’s was taken up there with enthusiasm. For a time more copies of Webster’s Dictionary were sold in England than in the United States, despite the explicit American character of Webster’s from the title page on. In a 1917 court ruling the name Webster on a dictionary passed into the public domain and anyone may now use it. Only Merriam Webster dictionaries trace directly back to Noah.

Nearly all the men who led the Civil War had learned to read and write from Webster, the tireless advocate of unity. Jefferson Davis had once in the Senate explicitly praised Webster and his speller. Only those who were self-educated, like Abraham Lincoln, had escaped Webster’s influence. Even a century and a half later, I grew up in the world of words he created. In high school Webster’s Dictionary was on the shelf. In college, purchasing a copy of Webster’s Collegiate was required. In graduate school Webster’s Enlarged was necessary to write that dissertation. When I started teaching I acquired the current edition. Regrettably I cannot trace the genealogy of the spellchecker to be sure but I hope it goes back to the brothers Merriam and from them to Noah.

Remarkable, energetic, and a polymath, Webster was many things. He was also arrogant, a know-it-all, a man who loved the sound of his own voice, a micro-manager, someone who did not understand the word ‘no’ when applied to him. He must have been a very high-maintenance individual. He also ha[ed the Constitution, fathered the copyright laws, founded Amherst College, taught a nation to spell, and brought forth that dictionary (and its many imitators that use his name) that remains a gold standard today.

Harlow Unger

Harlow Unger

Harlow Unger is the author of twenty-three books, most on individuals and themes from this same period in American history. There is a considerable body of research behind the book. That said, I found it hard to read – the prose oscillates from inscrutable to leaden to transparent, with too much of the first and not enough of the last. The emphasis is on Webster the patriot, as in the subtitle, and not on his personality or his dictionary. There is little of the inner man to be found in these pages. Nor is there much about how he went about the process that created that lasting testament, the dictionary. Those years occupy a small part of the book. Of course, no book can do everything, and I learned a lot from it. My thanks to the author.

‘Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen’ (2015) by Mary Norris.

This book from a major New York City publisher has had a big push. It pops up on web sites, newspaper review pages, NPR programs, and more.

I took the bait, remembering how much fun reading ‘Eats, Shoots and Leaves’ (2003) by Lynn Truss was. Inspired by reading that I tried Jacques Barzun’s ‘Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers’ (2001), and it, too, was entertaining and enlightening, but much heavier going, and at about page 50 I cut Jack loose. It was too much! It was like getting an assignment back from Miss Moses in junior high school drenched in the Red Sea of ink flooding over each page. (The name has been changed to protect the guilty.) She did not know when to quit and neither did Jack.

In ‘Between you & me’ the usual suspects appeared in the lineup. Among them were the evil twins Who and Whom, the hyphen, and the serial comma.

Who is on first? That is the nominative case. To whom did I give the keys? That is the accusative case (aka dative case). Got it? The doer is nominative and the done to is accusative. With me? It gets more complicated with noun groups and compounds, but I left the train before that. Their cousin, possessive case, Whose is best left for the advanced course.

The hyphen is just too hard for me. Compound nouns seldom take it but the words rendered as a compound adjective must. The boarding house fell down. But the boarding-house fire was bad. See? Sort of, but not for long. It turns out Herman Melville’s whale was Moby Dick but his book about Moby Dick was Moby-Dick. Sit down and think about that. Then there is breaking words over lines with hyphens. Is it at the first syllable. the first pair of consonants, or at the first meaningful break? Eng-land or En-gland or Eng-land. Two out of three? Grammar does not accept such populist methods of decision-making (or is that ‘decision making’).

My favourite is the serial comma which I learned way back in Hastings on the Platte to call the Oxford comma; so called because it was prescribed by the Oxford University Press, which was regarded along the Platte as the highest court for punctuation, though patriotism required Noah Webster’s spelling. The Oxford comma is that one before ‘and’ at the end of series, as in ‘eats, shoots, and leaves.’ This by the way illustrates one of the features of John Stuart Mill’s rule-utilitarianism. That last comma is not always necessary but it is best to include it because it is too time-consuming to decide if it is needed in this or that instance and that decision may be mistaken. Just follow the rule, and include it.

I have enlivened many dinner parties by bringing up the Oxford comma, discovering that some people invest much of themselves in that little squiggle, the ‘,’ and their cool, detached, and cynical demeanour slips entirely when it is bruited. People who yawn at important topics like man’s inhumanity to man, spitting by baseball players, or coal-seam gas, roll-up their sleeves for Indian wrestling when the serial comma is mentioned. (I feel free to say ‘man’s’ inhumanity to ‘man’ in the masculine since men are the principle culprits.) Defending the serial comma, I have alienated some guests who went away muttering never to return!

Back to Norris, there was a very informative and amusing aside on Noah Webster’s several efforts to create an American language, stimulated in equal measure by his patriotism and rationality. No less a figure than George Washington encouraged him in that endeavour. He had successes and he had failures. The ‘ou’ passed out of most American use and he made the ‘z’ do a lot more work than it did across the Atlantic, and, animated by the egalitarian spirit, he called it by its right name ‘zee’ and not that snobbish ‘zed.’ If it looks like a zee, acts like a zee, sounds like a zee, then call is ‘zee.’

Webster’s failures may outnumber his successes. His multiple efforts to match sound values to sight did not always carry the day, e.g., ‘cloke’ for ‘cloak’ and many of the same ilk died in the pages of his lexicography. I have resolved to read a biography of this Webster (and maybe one day Daniel Webster, too).

It was also an eye-opener to learn that any dictionary can take the name of Webster, and several have. But an heir to Noah always bears the name Merriam because the brothers Merriam bought the rights from the widow Webster when Noah died, and that company has continued to publish it. A dictionary titled ‘Internationl Websters’ or ‘Websters New’ is unlikely to have anything to do with the founder, Noah. I turned to my reference shelf and was glad to see that mine is a Merriam. I am now armed against such infiltrators in the future.

There was also a poignant moment when Norris quoted from a hand-written letter Jacqueline Kennedy sent to Richard Nixon in reply to his note of condolence when Jack was murdered to show how emotion is conveyed by punctuation. More importantly, to this observer it confirmed once again that Jackie was a higher being.