At 1 hour 10 minutes, 5.3/10 from 417 casters.

A missile appears on Soviet radar and the response is measured but finally an effort is made to intercept and destroy it. It fails, while intelligence reports that the missile did not originate in the USA or its allies. Huh!

The Soviet interception, while it did not disable the missile, deflected it into an Earth orbit. Around it goes at such great speed that the heat and sound in its trail destroys all. The new course will bring it over New York City in an hour. The countdown begins. (Note: the Russkies did it even they did not mean to do so.)

A misleading lobby card because there is no creature in this feature.

A misleading lobby card because there is no creature in this feature.

In Gotham we learn that a really big missile called Jove is soon due for a test flight at nearby Havenbrook. In New York City itself other scientists are making a bigger and better bomb; all are enlisted in finding a way to eliminate this threat. Among them is Robert Loggia, he of countless television programs, who spouts Geordie-speak and proposes to use Jove to carry the bigger and better bomb to blast the Lost Missile. He and his colleague Philip Pine, another TV regular, set to work against the clock. Tick, tick, tick…

Will exploding a hydrogen bomb in the atmosphere near New York City be wise? The Geordie-speak covers that. As the missile continues, it destroys Ottawa; no one noticed.

Only Philip Pine even wonders where the missile came from or with what intent and that is brushed aside by Loggia. Who cares? Let’s blow it up! Though admittedly, communicating with the silent runaway does not seem the obvious thing to do.

To get the plutonium bomb from New York City to Havenbrook, Loggia puts it in a Macy’s bag and sets off with his fiancée in tow. Sure.

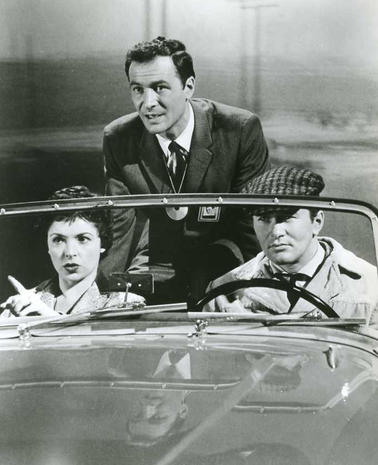

Loggia rides to the rescue and his own demise in one of his few leading roles.

Loggia rides to the rescue and his own demise in one of his few leading roles.

He sacrifices himself to arm the missile and launch it in the best Hollywood manner by installing the shopping bag in the missile, handling the plutonium. As crude as that it is, this is one of the few instances of movies of that era that emphasises the deadly radiation of nuclear weapons and atomic energy. Contrast that to ‘The Atomic Man’ (1955) where radiation is an annoyance to be treated with soap and hot water followed by a lie down and an aspirin.

Meanwhile, New York City is evacuated and those that stay in Gotham imitate Brits in the Blitz and gather in air raid shelters in a tense but calm manner to do the crossword puzzle. As if…

In between this action we see a lot, too much, stock footage of rockets, airplanes, weapons, wreckage, city streets, panic, and so on and on. These inserts seem promotional videos for the Air Force, for Conelrad, for NORAD, for Civil Defence, Macys, for…. One of them showed school children calmly crawling under their school room desks which would… (Remember that drill? I do.) Those inserts are good quality but pointless in the story. Perhaps sixty percent of the screen time is this padding. That made me wonder if the story was originally conceived to be shorter for a television playhouse program and then padded with this footage to B movie length.

The action with Loggia and company is well acted and briskly directed, but there is too little of it. Given that there is nothing about the origins of the missile, despite the misleading lobby cards with the hoary hand releasing the missile, it is hardly Sy Fy. We are none the wiser after it is blasted. Hope it does not have any siblings.

Again unusual for the time, the Soviets are shown to be cautious and the population of New York City includes blacks. Both are unusual for the time.

Common to the times is the role of the women to panic, cry, shout, and so on. Loggia’s girl is a scientist but you’d never know it after the introduction. She performs the stereotype duties well enough but there is no hiding how tiresome those duties are.

Category: Film Review

‘The Astral Factor’ (1976 and 1978)

3.7/10 from 575 at 1 hour 25 minutes

A slasher movie with invisibility and no slashes.

A convicted murderer reads a lot. Strange. He murdered his celebrity mother because she ignored him. HIs reading has given him telekinetic powers and also the on/off switch for invisibility. Wow! Mrs Hoover was right in the sixth grade when she said reading broadened the horizon.

The cast includes some name-recognition players: Sue Lyon, Elke Sommer, Leslie Parrish, Stephanie Powers, and Marianna Hill. Most of these women get one scene where they pretend to be strangled by an invisible man. Put that on the demo tape. On the other side, Percy Rodrigues is wasted though he imparts gravitas and integrity to a cardboard role. But the male lead is Robert Foxworth, about whom more later.

Back to the crazed killer.

His reading homework done, the villain, Sandman, uses his telekinetic powers and invisibility to escape the slammer and mow down the those enumerated above. The only incident that engaged the jaded attention of the fraternity brothers was the murder during a modern dance performance, and that was the choreography. Honest!

To get ‘The Invisible Strangler’ (alternative title) the master plan is to bait him onto a stairway and then remodel the house with gunfire. The bait at the top of the stair is Elke Sommer. Well, that would work. A step is loosened under the carpet so that it squeaks. Set! Wait a minute, who put the cat out?

Sandman is duly riddled in an NRA-approved fusillade. For about five minutes. End. Though how they know he is dead remains a mystery since he is still invisible, or did I blink.

Did not these people watch any of the Invisible Man movies? Evidently not. To flush out an invisible man or woman, blow smoke, pour water, vent steam, spray insecticide, use paintball, something. But not here; instead it is a hail of bullets.

To attract the slasher demographic the alternative title was used when it was finally marketed. ‘The Astral Factor’ is never explained in the film anyway, and it would just confuse the anti-vaxxers. Mondays do that, too.

There were no special effects. No floating glasses, moving telephones, and since he strangles there are no wafting weapons. Nor is there any problem with invisible clothes and shoes or going bare and barefoot. Nor is there ever any explanation of how Sandman does it. Who cares anyway? (But which book was he reading? )

It was made in 1976 but not released until 1978 for the desperate VHS market of the day.

Seeing Robert Foxworth reminded me of one of the most enjoyable movies that has ever come my way, ‘The Black Marble’ (1980). It is a police procedural that is sad, funny, romantic, idealistic, pragmatic, has dogs, a chase, singing, and gave me an appetite for St Petersburg Russia, which was satisfied in 2017, though not in August. I re-read Roger Ebert’s laudatory review from the time and agreed with every word and sentiment. Foxworth is the movie but it helped to have that Amazon from Texas, Paula Prentiss, and the desiccated Kentuckian Harry Dean Stanton alongside. Joseph Wambaugh, the author of the novel, one of many, felt that previous Hollywood renderings of his books were stupid and superficial, so he decided to do it himself with this one. He succeeded! Chapeux!

‘This is not a Test’ (1962)

A boring film of 1 hour and 13 minutes about a nuclear apocalypse. It is marked as 5.5/10 from 557 time wasters.

A highway patrol officer in the Alabama Hills near Los Angeles is ordered by radio to set up a one-man road block in the middle of nowhere because a fugitive is about. He complies.

For nowhere there is lot of traffic and each time he orders the driver to stop, pull over, and wait without a word of apology or explanation. Send him back to the training course, cried the fraternity brothers. The motorist are varied.

Yes, this the Otranto roadblock where a mixed group of individuals are thrown together by larger, external events and must interact with each other. A disaffected wife sneaks off into the bushes, unbuttoning her blouse with the virile truck driver, a worried businessman has to fly to Mexico, a drunken socialite wants more liquor and her ageing beatnik boyfriend wants to match macho with the police officer who promptly clocks him with a rifle butt. This is a man of few words.

Copper forbids them from returning to their vehicles and has pocketed all their keys, hence no one can listen to commercial radio. The only source of intel is the police radio which begins to talk about evacuation of the city with the title phrase, ‘This is not a test.’ Everyone of a certain age will recognise the title as the Conelrad alert for atomic armageddon. Sixty minutes is mentioned as the time to….. Transmission ends.

The police officer redoubles his efforts to keep the party together, get those two out of the bushes, whack some sense into the would-be beatnik, kill the socialite’s annoying dog by strangling it, and coerce the truck driver and his off-sider to empty the truck. Why? So that it can be used as a bomb shelter! Yep. Well it is better than nothing. That was one training course he did.

So they crowd into the Otranto moving van truck which just happens to have a supply of canned food and bottled water, well beer. There was not much bottled water in 1962. Everyone in the truck feels sorry for themselves and has to decide how to live the remaining hours of their lives. Mostly they stand around saying that. They need an agenda and chair to focus the discussion. They need a McKinsey-speak manager to confuse things properly with micro-managed KPIs.

One hopes that in the truck’s supplies there is plenty of deodorant, because they may have to stay there for months. So it is said. It varies between oblivion in sixty minutes or months of waiting while the radiation dissipates, and that seems to be realistic in a way. Who knows? Who has tried to sit out a nuclear war in a truck before?

In 1962 nuclear war was a reality though the Soviets are never mentioned, and there is no chest-thumping about the American way in the back of the truck. Ergo it is certainly of the time but subdued. There are many films with a similar setting, like ‘Five’ (1951), ‘Alas, Babylon’ (1960), ‘Ladybug, Ladybug’ (1962), and more. Each of these three has a lot to offer.

Like many of those other films this one is intended to be a taut character study, but, well, it never had a theatrical release, not even for the triple feature drive-in market, where the cheap schlock was always welcome, and it is easy to see why. It is not taut though it is confined like a stage play. The writing does not produce or reflect tension though it is combative. The characters are so shallow, who cares. The more so when compared to the films named above. It seems to be the only credit for the director, screen writer, producer, and lead actor. The cinematography is either bleached or shadowed.

The Easter Islander playing the lead is monosyllabic and seems to have no inwardness. Some the players are familiar like Thayer Roberts, the farmer driving a crop to market and Norman Winston as the husband who shoots himself, not at the prospect of incineration but because it was his wife off in the bushes with the truck driver. In the hills the fugitive is still after the one-armed man.

However, despite its qualities, the film brought back a lot of unpleasant memories from that time and place when nuclear Armageddon was a prospect. The drills in school. The repeated testing, as in ‘This is a Test’ of the Conelrad network. The public service announcements on television about taping windows in preparation for annihilation. The ominous announcements in October 1962. Then there was the ordinary high school day when we were sent home early without explanation. Gulp! I have never been able to watch ‘The Day After’ (1983) because I thought I would relive that.

‘Munich’ (2017) by Robert Harris

A novel about two underlings in the negotiations at Munich in 1938. Years ago I read Georges-Marc Benamou’s ‘The Ghost of Munich’ (2009) concerning the late-life recollections and reflections of

Édouard Daladier, the French Prime Minister who took part along with Neville Chamberlain.

The stereotypes of this episode are many and seldom varied. Too bad. Harris, as always, digs deep into the strata and finds complexity, contradictory strands, variation, mixed motives, and men in way over their heads in deep and dark water where there is no bottom to touch.

In the main the reader looks over the shoulder of the youngest of the private secretaries in Prime Minister Chamberlain’s office, Hugh Legat. At times we see his Oxford friend, Paul Hartman, sometimes it is implied ever so delicately that they were very close and more than friends, who has become a translator in the Wilhemstrasse Foreign Ministry. They meet at Munich.

Much of the novel demonstrates the great pressure Chamberlain was under to find a way to peace and avoid another blood bath, his heart-felt desire to do that, his unflagging energy even at age seventy to pursue every last chance to the Nth degree, and his creative strokes in keeping the peace-process, as we have since learned to call such negotiations, alive on the assumption that talk-talk is better than kill-kill. He emerges as a good swimmer destined to drown in a mighty tsunami.

While the sniping from the Churchill lobby is noted, the real problem is always Hitler. He is the swirling eddy sucking everyone else into the maelstrom. Harris is a master of the detail of the Nazi regime down to the buttons on the uniforms of the waiters, and yet if comes across easily.

Chamberlain’s most creative stroke was to draw Benito Mussolini into the conference and that did buy several days, a week even. Hitler could hardly refuse the participation of his one and only ally, and Mussolini liked a stage and made the most of it with his prolix German and French. But here he is relegated to the wings.

Daladier said virtually nothing, so exhausted and preoccupied was he by the back-stabbing and internecine struggles in Paris that he spent most of the negotiating sessions making plans to do down some of his host of opponents at home. Among his own dwindling supporters some rallied under the banner ‘Better Hitler than Blum,’ the socialist Jewish alternative.

Chamberlain’s second stoke came after the partition of Czechoslovakia was agreed; it was to extract from Hitler that piece of paper he brandished at Heston aerodrome. At the end of the formalities in Munich he asked for a private meeting with Hitler and presented Hitler with a joint statement that paraphrased one of Hitler’s own recent speeches about peace. Clever that. Although Hitler had no interest in seeing Chamberlain he did so, he said, out of courtesy. Still less did he want to issue a joint statement, but he could hardly repudiate his own words just then. Moreover, it was just a piece of paper so why not sign it, if for no other reason than to get Chamberlain to leave. So he did and he did.

Chamberlain is shown to be a terrier about details throughout and to have an encyclopaedic grasp of the situation. He is also aware of how greatly people wanted peace.

Indeed, one of the interesting elements in this telling is the jubilant popularity Chamberlain had in Germany where the women and men in the street saw him as a messenger of peace, and cheered his every appearance. They crowd around the hotel and call for him to appear, but he does not do so in deference to his host. This popularity annoyed Hitler, who darkly grumbles about the problems with Germans weakness.

There is much in the book about how the PM’s office worked, relations with the cabinet, and with the Foreign Office, that shows the stage machinery of such dramas as well as the rivalries. As always Harris has immersed himself completely in the subject. Likewise, we read much about how Hitler’s entourage was organised at the time, as Hartman is drawn into it, and then recoils from it.

Legat and Hartman have their own private dramas but the master narrative that unites them and propels the book is this. What if Chamberlain (and Daladier) knew for a fact that Hitler’s intention was to go to war? Would that knowledge have led to a change at Munich with a different result?

I included Daladier about in parenthesis though there is virtually no liaison with the French shown in these pages. The French were paralysed by their own domestic strife and were present only in body. In Benamou’s novel Daladier is fatalistic. War is coming and there nothing to do but wait, and then he had faith in the Maginot Line. He is more worried about the prospect of a French Civil War similar to that in Spain.

Legat and Hartman offer such proof of the bellicose intention, and Chamberlain refuses it. Intentions can change, he may have believed, and maybe here today we can influence that change. Moreover, there is no advantage in being seen to be the aggressor. He is perfectly aware of the fact that a signature on a peace of paper will not stop Hitler from doing his worst, but it will give England the moral high ground. And it might delay the inevitable if it is inevitable for a few more days.

Furthermore, Hartman’s suggestion that an aggressive Britain would precipitate a coup d’état against Hitler is so much wishful thinking. Everything the Brits saw in Munich convinced them that Hitler had complete control of the country and that fit with every other source of intelligence they had. To be sure there were dissidents but they were but fleas.

Appeasement to use a word that barely figures in this text is the term usually associated with the period immediately before World War II. In its earliest days, when Germany reclaimed the Saar, and the Rhineland, and unilaterally cancelled some debts, appeasement was a positive policy by England, France, and Italy to assuage some of the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been imposed upon Germany at the insistence of Georges Clemenceau who wanted forever to cripple Germany. Subsequent French governments wanted, not to ease the German plight, but to strike at Clemenceau’s legacy for momentary political advantage, and so acceded to British initiatives to relent. The Brits wanted a German bulwark against Communism from the East.

But the demands from Germany continued, and no one in France or England wanted another war. While England and France had won in 1918, the war nearly destroyed both. Peace was popular, very. In addition internal political turmoil in France was paralytic as its own fascists were inspired by the Italian and German examples and the Spanish Civil War. Italy soon went with the wind into Hitler’s camp. The French hated each other more than any enemy and locked themselves in a battle to the death; that is no exaggeration because there were assassinations and beatings aplenty.

Chamberlain had learned the value of publicity and ensured that the press with BBC news cameras were waiting his return, though Harris is silent on this point, and in the wind after a rain shower he made that much quoted remark with that peace of paper in his hand which promised ‘Peace for our time’ but I have heard it said that this seventy year old after the arduous days in Munich where there was little sleep and no rest misspoke and meant to say ‘Peace for a time.’ By that measure it was a success.

It is certainly plausible but Harris passes on this possibility in silence.

That possibility reminded me of Neil Armstrong’s much quoted 1969 remark ‘one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’ Wikiquotes now does Armstrong the service of inserting an indefinite article in from of the noun ‘man’ so that it reads: ‘one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.’ But accompanying sound file has no ‘a’ in it. The commentariat has been squeezing ego-time out of that ever since.

What else then could Chamberlain do but buy time, and hope against hope that the winds might change, and those cheering crowds in Munich heartened him, though his long political experience meant that he did not bank on an enduring vox populii.

For some years I was an HSC examiner and read each night for three weeks countless, well in fact they were counted — eight an hour — handwritten scripts on Modern History examinations on appeasement and this era. The words occasionally swam before my eyes but on it went but I learned a lot, about both the subject matter and the high school examination process, though as to the latter I was disappointed by its mechanistic rigidity, no paper could be awarded the highest grade of twenty unless it had mentioned every possible point on the list, emphasis on list. Out of the scores I read there was an outstanding one that was intelligent, well written, insightful, and probing but which, because of its tight focus, omitted a single point on the checklist and so, despite my advocacy, it was docked. That still rankles all these years later. (There were many other good ones but I refer to the one I tried to promote. Thereafter I learned my lesson and did not push.)

While indulging in autobiography, I spent a day in Munich in 1983 in a driving rain that inhibited much sight-seeing but I did find the bookstore that figures in a few episodes of ‘Derrick,’ a long running German cop show on SBS.

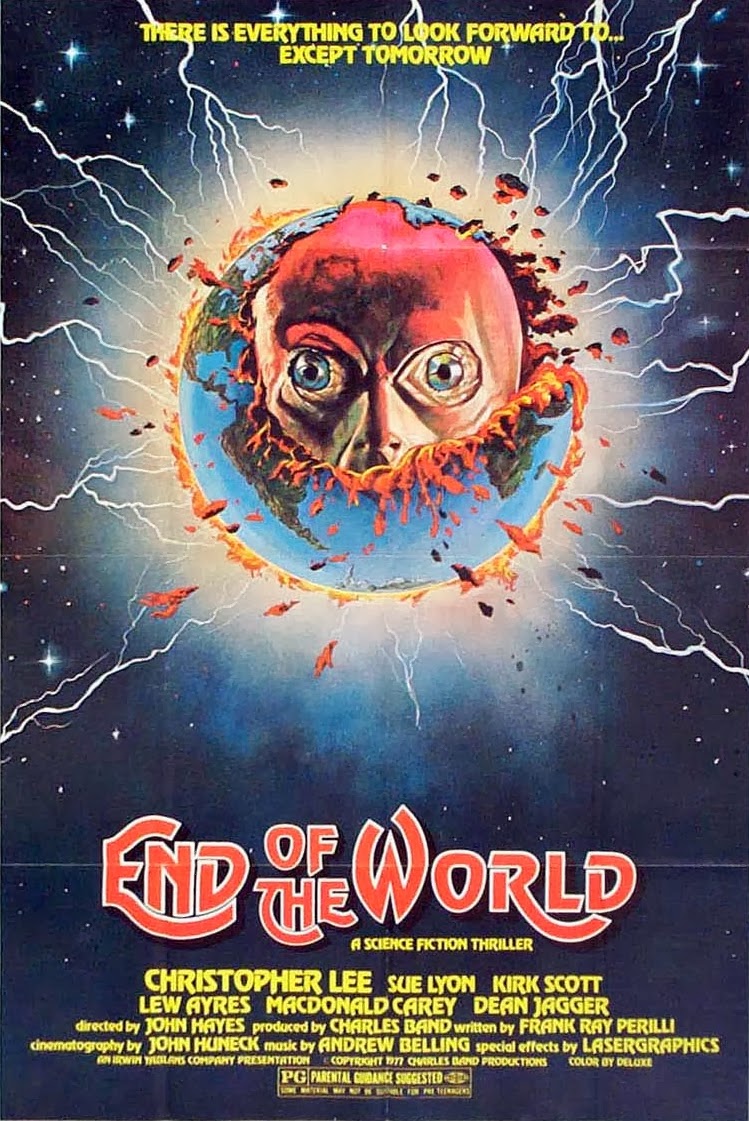

‘End of the World’ (1974 and 1977)

Starring Christopher Lee and Lolita, this was released in the same year as ‘Start Wars.’ That is the only thing they have in common apart from the genre classification of science fiction. This one is in the class ‘End of the World’ films like ‘Doomsday Machine’ (1967 and 1972) reviewed elsewhere on this blog and watched on consecutive nights. Contra T. S. Eliot on both nights it ended with a bang, not whimper. ‘Start’ for ‘Star Wars’ is the fraternity brothers’ idea of a witticism, since that first film started the endless franchise that is still with us.

This entry runs feature length of 1 hour and 28 minutes; by the end we all wanted it to end. The End of the World was a small price to pay for the relief. On the IMDB it rates 2.9/10.0 from 654 votes. That comes in below the average excrescence from Adam Sandler, but 0.5 ahead of ‘Doomsday Machine.’

It starts well, and that has trapped a lot of viewers per the comments on the IMDB. The cadaverous Lee in a Catholic priest’s garb with a vacate look blunders into an all-night dinner; no one else is there but the attendant. Lee is sub-verbal, like a 7MATE announcer, but looks like the survivor of a car wreck. Stunned, dazed, off-centre, and muttering about calling the police. OK.

Then the telephone explodes off the wall! That’s Telstra service! Anyway, then the coffee urn explodes and the whole place goes up in blazes. Lee stumbles into the dark and ends up in front of St. Demon’s church, where he is greeted by …. himself! This is a mysterious start…and most of the mystery ends there, too.

Meanwhile we see Square Jaw sitting at a 1970 dumb computer terminal in a room full of clicking, spinning, blinking gizmos, so we know this is hi-tech. We see a lot of him sitting. He’s good at it. Sometimes he smokes a cigarette in this hi-tech environment. Then he sits some more. Occasionally he furrows his frontal lobes. Is this gripping or what? “Or what,’ said the fraternity brothers.

After what seemed like twenty minutes of furrowing, he says he is receiving messages from S P A C E. No one cares. His boss, the redoubtable Dean Jagger (what porkies was he told to take part in this travesty?) wants him to get back on schedule and forget this nonsense. Stick to the KPIs! Lolita just wants to party.

There must have been a sweet talker in the production because some of the footage is from the Rockwell plant where a space shuttle is under construction. This part is limited but it is impressive.

In the best tradition of a earlier era, Square Jaw takes Lolita hither and yon. No doubt the director knew who viewers wanted to see more.

They go to a super secret facility and walk in to find Lew Ayers who injects gravitas and humanity to this connect-the-dots exercise. More on Ayers below. We never see him again, nor is any use made of the gobbledegook he spouts from the screenplay.

They go to St Demon’s which is a convent and nose around. They nose around some more. Square Jaw exerts his lobes again.

Most of this movie was evidently filmed at night, in the dark, and through a fish tank. Much is not seen and every comment I found on the inter-web said that, so the print I watched was not unique.

Spoiler.

It turns out the alien garbage crew has landed. These aliens have duplicated Lee and the nuns at St Demon’s, though the real Lee keeps wandering about. (He rehearsed this role earlier in an episode of ‘The Avengers [1965].) No explanation of that. The avatar Lee explains that the Earth is a menace to the universe with its pollution, 7Mate, wars, hideous advertising, immorality, lousy presidents, and he and his crew of nuns have come blow it up.

Today that message has resonance about the pollution and destruction of the Earth but in 1977 it sounded dopey, the more so when joined with moralising about how evil humans are. That is, considering the the avatar Lee boiled the short order cook alive in the opening scene, and murdered a few others along the way, including his alter ego. Is he above reproach, not hardly.

With that explanation avatar Lee sets the bomb ticking and his crew step through a portal to go home, as avatar Lee steps up he invites Lolita to come along and Square Jaw, too. in an after thought. The former the fraternity brothers could understand but not the latter. Anyway without a word of demur, they do so.

After all, the news on CNN is that the world is ending. Kaboom! The END of the movie.

This is a production that languished without release, until it was bought by another producer and sold to the late night television market, where it continued to languish taking a few unsuspecting viewers with it.

In the paranoia of the 1950s witch-hunting, Lew Ayers became suspect to the Tweets of the Time in a whispering campaign. After all he had starred in an anti-war film early in his career. This, they alleged, set him on the Red path as a fellow traveller. The film was ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ (1930). Worse, in World War II he had served as a front line medic, rather than carry an NRA approved gun. His film career slipped away and he turned to television. Many years later inspired casting made him the incoming President of the United States in ‘Advise and Consent’ (1962) and that put him back on the wide screen.

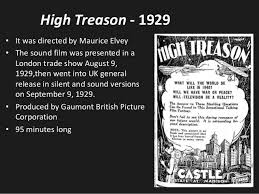

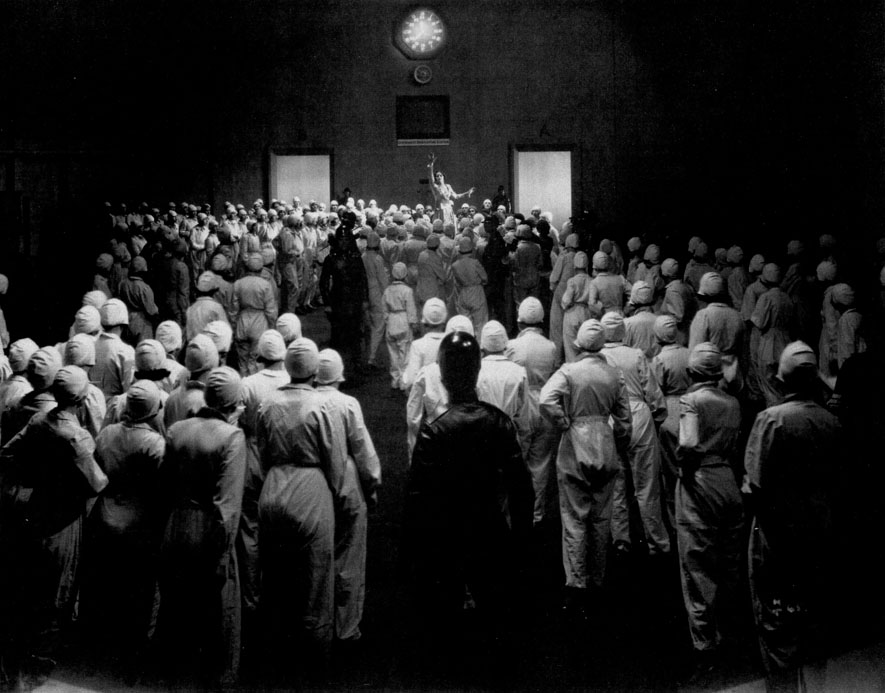

‘High Treason’ (1929)

From the IMDB: 1 hour 35 minutes and 6.2/10 from only 88 opinionators

A movie made on the cusp of talking pictures. It was made silent and then shortly thereafter a soundtrack was added, though the inter-title cards from the silent version remain. It is called the British response to ‘Metropolis’ (1926) with its futurism rendered by miniatures.

It is set in the far distant future of 1950 where face-time phone calls are the norm at the top of the social pole.

We never see any proles. Everyone of the elite scoots around in a personal airplane. Art Deco is über alles. The gear is all sleek and flapper with cloche hats. Fantastic, perhaps, but the clipboard is much in evidence. Not a computer in sight. But rows and rows of clerks adding things up. What things? Dunno.

The post-Great War world is divided into the Federated States of Europe and the Atlantic States, as illustrated on a map. Did Eric Blair see this movie?

Somewhere there is a land border between these two. Greenland? Bermuda? Wales?

At the border the opposing guards play cards and joke about another war. A futuristic car pulls up and much suspect behaviour ensues. Will they declare the duty free or not? Not! Finally the car breaks away and shooting follows. The guards in the best NRA training start shooting each other rather than the fleeing automobile, which looks like a low-slung rocket on wheels. We never do find out what this is all about except that the guards are trigger happy, and that is well conveyed.

The blame bat swings and the politicos on each side of the border pontificate and bluster. All this is observed over a tele-screen by a room of bearded men in a smoke filled room who are spying on the politicos and brag about manipulating them. These are the plutocratic merchants of death. They are indicted by the film for encouraging war, but how they caused those border guards to go all NRA is never explained.

Once the bluster starts it has no end. See Barbara Tuchman’s ‘The Guns of August’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

In a parallel path we have the World Peace League, which is compromised mainly of women who wear white. There is a lot of white. There are millions of members, but, of course, the head is a man, ahem, whose daughter is betrothed to a soldier. The Montagues and Capulets at it again.

When Romeo and Juliet go to a ball and dance there is marvellous scene with an automated orchestra and a mechanical dance. The scale is great but the movements are stiff and poorly timed, by purpose, to reflect the pace of the instruments. At least that is what I think the point was.

Dad Montague is president of the Atlantic States and keen for war. No reason is offered for his belligerence; he is just written that way. Romeo Montague is a pilot who is ordered to bomb the Federated States of Europe, which is headquartered in London. Juliet Capulet in white harangues one and all campaigning for the Nobel Peace Prize or at least the Sydney one.

There follow two confrontations. One is choreographed like Busby Berkley at the aerodrome between the bomber pilots in slick black leather gear, and the women in white, lots of them. They mill around, confront, mill some more, while Romeo dithers. This scene is very nicely staged. The pilots have to get to those boy toys so they can blow people up, and quick! Guns are drawn, but…

Meanwhile, Dad Capulet in white goes to see President Montegue in his private sanctum. In passing we learn that many chaps are keen for another war, though there are some chaps who know better in white, too. Not a white feather is sight. Boys Own stuff. This man of peace carries in his pristine, moral high ground white clothing a gat. A smile comes to the NRA composite. Got a problem. Shoot it! Problem gone.

Ah…. Peace now prevails in this world of personal rule. No more detail about this miracle is offered. If Hitler had been murdered at Munich….? Well, then perhaps Reinhard Heydrich for Führer. Gulp.

Instead we have the trial of Dad Montague in white for murdering President Capulet in black. The judge, determined to make the law an ass, rules irrelevant all matters of context and intention. A life for a life is the rule he knows. Though the jurors are anguished cravenly they comply with the direction of the judge, and he is sentenced to death, left then staring at the camera, while Romeo comforts Juliet. He never seems to note or care about the murder of his dad. Will the Federated States now launch an attack. Unknown. Maybe they are having their own white and black confrontation. Who knows.

That is where the version I watched faded. Fine with me. It is available for Free View from BFI web site, but I cannot access that. I found it on the Internet Archive and mirrored it to the Apple TV.

The futurism is fun, and the extended Art Deco set design and costumes are noteworthy. The comparison to ‘Metropolis’ is right for the staging, but not the story. War and peace is a big subject, true, but here it reduces to the bad will of a single individual, President Capulet. There is never any indication that the beards with cigars have any influence on Prexie Capulet and they disappear from the film. Or will they return to manipulate his successor into war? ‘Metropolis’ offers a more complex account of good and evil. Nor are there the macabre touches from ‘Metropolis.’

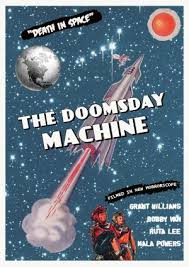

‘The Doomsday Machine’ (1967 and 1972)

Start with the IMDB information: 1 hour and 23 minutes, with a score of 2.4/10 from 761 brave souls.

It is also a fact that it has two dates. The core was filmed in 1967. Notice the bouffant hairstyles and the hairspray required to hold them in place. The film, however, was not released until 1972 when a creative entrepreneur bought it, and proceeded to cut and paste into and around the core excerpts from two other, as yet unidentified movies, to produce this pastiche. Ordinarily such comments about production follow a discussion of the film but in this case they offer an explanation for the mish-mash.

Let’s try to take it in turn. It opens with a woman sneaking into a secret (but poorly guarded facility) and since everyone looks California Chinese we are to conclude it is RED CHINA! This woman is a spy and she proceeds to murder the hapless security guard. Evidently the budget cutters had been at it and reduced the security to this schmo. She also — and the fraternity brothers liked this touch — strangles a lab technician with her own pigtails. She also stabs another lab rat who happens along. With her blood lust sated, she then examines a throbbing mechanism. Imagine what the fraternity brothers made of that.

Next she is seen behind a slide carousel (that’s a memory test) projecting pictures of the aforementioned mechanism to a room full of hirsute men with yacht sails for neckties, saying only Chairman Mao has the key for it. Heavy! They conclude it is a Doomsday Machine and pick up the phone to call the president in Florida on the golf course.

This is part one and it is lifted from another film entirely and we never see any of these characters again, but it justifies the title that was put on in 1972. It is all poorly staged, acted, lit, photographed, and very unbelievable. Not even the Twit-in-Chief would fall for it. Hmm.

Now we come to the core which has an airforce mission to Venus in preparation. NASA is nowhere to be seen but there are many blue uniforms and much saluting. There are seven men, straight and tall, ready to go. Much banter among them. Much stress on the physical rigours that await them, and their superb preparation. More saluting.

Then a car pulls up, security here, too, is lax, because a civilian emerges. Suits are always bad news among uniforms and this suit has three women in tow, but at least they are each in uniform. Gasp! One of them is in a brown uniform with a Red Star on it! Gasp. A Russky! Gasp! [It goes on like this for a while.]

By order of the Twit-in-Chief, three of the men are stood down and the three women replace them. Much amazement among the men that a woman might be a flight surgeon, a space pilot though this patricianly specimen was the first woman on the Moon, and an astrophysicist. Uniforms, military rank, a bushel of advanced degrees these they may have but they are WOMEN!

However ‘ein Befehl ist ein Befel’ and Colonel Physique submits, though he asks repeatedly why, especially as to the Red Russky. The long established plan is abrogated and they are launched toute suite, without a lot of TSA pre-flight checks. Again there is no explanation for the rush, but viewers know it must have something to do with Chairman Mao.

In sum, we have three young men and the old codger along with three nubile young women with bouffants. The fraternity brother had no trouble following this.

Sure enough the codger goes crook, and the women look after him, when not serving drinks. Colonel Physique strips off his shirt, and on him and this more below to reward the persevering reader, and parades around bumping into the women in states of undress. ‘This is ridiculous!’ he shouts. So did we. The visual evidence confirms three young men and three young women.

Pairing begins immediately when one unstable, snivelling male, let’s call him Donald, jumps on one of the women. So this the elite of the best of the best. His approach reminded the fraternity brothers of things they had seen in the zoo. The object tries to put him off, short of belting him. ‘No’ is not the answer Donald wants, and we all knew ‘he’ll be back.’

Meanwhile, they lose contact with ground control, because…. there is no longer any ground. Turns out the China Syndrome was right. Bored one night, Mao turned the key on the throbber and it split the world apart. Gasp! They watch the CNN broadcast of the end of the world, but give it a stingy two stars. Bang. No more Earth. Ah ha, that is why the women are on board. The United States Air Force has sent Adams and Eves in space with that codger as chaperone, though why a Russky was included still baffles Physique.

As usual, a meteor has crippled the ship and radiation is bad so they apply much Reynolds Wrap Heavy Duty here and there to fix it up. But they have used too much fuel outrunning the debris that once was Earth and dodging the meteors. Meanwhile, Donald continues to harass the object of his extension. In fact, and this is a first for the Sy Fy seen thus far he tries to rape her, in an airlock.

Remember how lax the security has been everywhere? Ditto for airlocks. There is a big red button with a sign in 8-point type that says Do Not Push. In their struggle it gets pushed and the load is lightened by two as they are blown out into space. Donald, OK, but her, she was the victim. There is no justice in space.

Still the load is too heavy to reach Venus. Whoa. Almost forgot Venus, and so did the director and producer. They talk about throwing each other out to lighten the load.

‘Why didn’t they use the hairspray aerosols for propulsion?’ cried a fraternity brother. ‘Why not ditch the codger? asked another. A third, suggested that they jettison the hairspray tins and the brushes, combs, and other impedimentia seen earlier. In fact, he suggested they ditch their clothes. These boys are smart despite their grades.

In the meantime one crewman and the Russky in space suits clamber outside the ship to repair a tear in the Reynolds Wrap and accidentally on purpose the rocket zooms out from under them and the are lost in space floating. They make comic relief remarks.

But by chance, in the vastness of space, there floats by a Russky spaceship. Is that handy or what! They board… Wait.

Here is where another, third film is cut and pasted in showing two completely different people in different space suits entering a ghost space ship where they find the crew dead but the ship fully operational, though it is the comic relief man who pilots it, the Russky ship, and not the Russky woman pilot with him. No women drivers in space. Note for pedants. These space suits are not those originally made for ‘Destination Moon’ (1951) and used repeatedly in other films since that year. Either they were worn out when this clanger was made or they were checked out to an Apollo mission.

They radio the mother ship [get it] and there is much talk of heading on….

Cut back to Adam and Eve, oh and the codger is still looking on and moving his lips about the future. An eternal optimist.

At this point a title card came up: The End.

Word on the inter-web is that the producers of the original film about the Venus mission went bankrupt before filming the Venus part and that is why it went on the shelf in 1967. The new producer spliced in other stuff and added a voice over ending with the codger rabbiting on about little rabbits or something to sell the resultant turkey to the drive-in market.

Roger Corman also spliced in various visuals of the destruction of the Earth from public domain news footages of fires, floods, GOP majorities, and other disasters, passing space junk, including two or three ersatz space stations cribbed from other movies and which were never noticed by the crew, and many different rockets. The ship they set out on morphed into two later configurations. Ditto the space suits as noted above.

The comic relief by the way was played by that triple threat performer Bobby Van, cannot sing, cannot dance, and cannot act. Confirmed. Confirmed. Confirmed.

Physique is played by Denny (Scott) Miller, a Hosier. whose stint as the title character in ‘Tarzan, the Ape Man’ (1959) left him forever shirtless. His parents were physical education nuts and passed it on to him. He went into television and had a long career as an extra, often unnamed. I recognised him from something but could not identify it, though he was recurrent on ‘Wagon Train’ (1961-1964). Although his real claim to fame is that he played basketball at UCLA. Most Hoosiers are born with cross-over dribble in the blood.

His Eve was Ruta Lee neé Ruta Kilmonis from Quebec, who likewise had a long subsequent career on day-time televisions soap operas up to and including 2017.

Mike Farrell has a few early lines as a journalist, before he went to Korea.

‘The Amazing Transparent Man’ (1960)

After completing the Invisible WoMan spin offs, this seemed the next logical title. It was all the more intriguing for being directed by Edgar Ulmer whose ‘The Man from Planet X’ (1951) and ‘Beyond the Time Barrier’ (1960) had merits and his ‘Detour’ (1945) has many rave reviews. That was enough for me to tune in.

It starts with a boring jailbreak where the villain climbs a wall and hops into a hot convertible driven by a moll. In the dark he sheds his prison stripes for civies and in a moving car without the aid of mirror he ties a bow tie! Wow! This is a man to watch, as long as possible.

Note the bow tie.

Note the bow tie.

I knew then why his name was Joe Faust. He had already sold his soul to the devil if he could do that.

The convertible was driven by B-picture stalwart Marguerite Chapman, who topped the bill in ‘Flight to Mars’ (1951). Her childhood nickname was Slugger and it seems she lived up to that name in later life as a few wanna be Lotharios discovered. Now if she had just knocked some sense into this screenwriter.

James Griffith, familiar from 1950s television, wants Faust to steal radium for experiments he is running with a coerced German scientist whose daughter he is holding captive. Faust was in the slammer as an ace number-one bank robber, and so knows a thing or two about vaults, entering and exiting there from.

So far, so what, but…Griffith wants radium for transparency experiments. The word ‘invisible’ was never used, and I listened for it, as I am sure the lawyers for the Universal franchise did too. His German scientist, who gives the only creditable performance, can render living beings transparent for brief periods but he needs more radium to perfect the process and extend the time. Of course with prolonged exposure one becomes dead and buried, beyond transparency.

Faust talks tough but agrees quickly. Faust by the way is a behemoth and why he did not just muscle his way out then or later passes belief. Griffith is no match for him on any score and his one measly henchman sleeps most of the time. It is so hard to get good henchmen in B movies.

Faust steals some radium and has fun assaulting unsuspecting people in his transparent state. Since funds are needed he decides to do likewise in a bank where a wad of cash is conveniently bagged on a table top. Off he…, whoops, the transparency juice wears off and he passes into and then out and then back into whole and part visibility. The effects are good but very brief and not well centred.

Marguerite and Faust plot against Griffith and in the resulting showdown the radium is ignited. Kaboom. End.

Earlier the daughter was freed, and she had a non-speaking part and stuck to her amazing silence, and the scientist was liberated. These two survive and he offers the last line asking the audience ‘What would you do?’ The question is about the secret of transparency but most of the audience was surely already gone by then. They knew what to do: L E A V E.

Griffith is referred to throughout a major. He seems very unmilitary and there no explanation. At times he waxes on about a transparent army. His unseen army would have an advantage over the invisible characters from H. G. Wells because they would be clothed. When transparent Faust remains clothed. Huh? Yep. When he comes to light in the bank he has his clothes on. Never tried putting on a pair of invisible pants myself but…. don’t want to try. Would the weapons of this unseen army also be transparent, and if so, how would they ever find them.

The imprisoned daughter is in a bedroom upstairs. Go get her would seem the obvious solution. The gunsel has no loyalty to Griffith and with a word breaks from him. Within five minutes of snarling, Marguerite is in with Faust who hulks and towers over the whole rest of the cast assembled. Talk about a house of cards.

Ulmer did not apply himself, is all I can conclude. Nothing is made of that name Faust. There is no science in the transparency. Just dim the lights and poof! There are no sight gags like floating telephones or drinks. Just guys pretending to be punched and falling over. The fraternity brothers can do that after a night on the keg!

Still less is there any reflection on the advantages and disadvantages of transparency, like finding the pants.

The set, apart from the convertible, is an A-frame farmhouse. Most of the acting looks like it was done in one-take. Yet it was shot back-to-back with ‘Beyond the Time Barrier’ using the same camera crew and so on. This latter film has a poor story but it has some intellectual content and a distinctive visual style. Ulmer’s earlier ‘The Man from Planet X’ had an ethical ambiguity that was intriguing. Here we only have the heavy hand of Joe Faust slapping people around.

In sum, it is not Sy Fy but a very cheap and nasty film noir done in five days for the drive-in market. None of the characters are engaging. Even the grey-beard scientist who freely and quickly admits to having performed experiments on live human subjects to earn his crust. These victims included his own wife. So how come he goes all gooey about a daughter? Was she on his Green Card? Does he need her to remain eligible for his next role? Does art imitate life?

On IMDB 3.8/10 from 1,782 brave viewers. Run time: 58 minutes.

Dare I suggest that the 3.8 is boosted by the short running time. If it had been longer, the score would be lower.

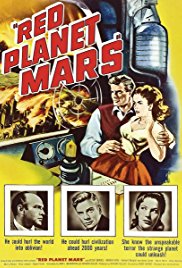

‘Red Planet Mars’ (1952)

Running 1 hour 27 minutes, 4.9/10.0 from 904 opinionators

The sagacious Finn Janne Wass gives it 1/10 and still that requires justification. Read on.

It is very well staged, acted, and photographed. though conspicuously lacking flying saucers or Martians. The laboratories are well stocked. The telescope looks serious and not cardboard. The interiors are fully furnished in Palm Springs, perhaps owned by someone in the production. The acting is fine. That is the good news.

Then there is the script and direction. There are too many speeches about nothing much to slow things down and pad it out to feature length. Some of that may be down to the director who does not give pace a priority. There are bumps and drags. But the greatest problem remains. Before getting to that, some context.

The dumb blonde Peter Graves is a radio astronomer who has a home laboratory where his wife assists. He collaborates with Distinguished Professor who has a big telescope. There is much blah, blah, blah. The Prof has photographic evidence of the Schiaparelli canals on Mars and has observed how the polar ice cap is melted into the canals. (These canals were born of the fertile imagination of Giovanni Schiaparelli [1835-1910].) This is proof of intelligence at work! What other explanation could there be, Erich?

It fits because Blonde Peter is getting radio messages from Mars, sort of. He is sending to Mars and later he gets a reply that is identical to his message. It is not an echo, that has been checked and ruled out. So he says ‘tomato’ and later the reply comes ‘tomato.’ It is the way a child might repeat what a parent says to it. This conversation is so boring, Peter will never get another research grant unless he can move things along.

Peter doing his dumb blonde routine.

Peter doing his dumb blonde routine.

Ah ha, an MIT graduate, Blondie decides to send the mathematical constant, pi. Why didn’t he think of this earlier? Well he is a dumb blonde. The Martians will recognise it and extend the result, and… Not only is this a mathematical constant, it evidently is a universal. Huh?

The Martians use the decimal system and Arabic numbers? Clever those redskins. Oh and Morse Code, too, since that is what Peter uses to send.

Worse the explanation of pi is inverted while it also asserted in this garbled dialogue that one cannot have, make, or use a wheel without knowing pi. Oh. Even the fraternity brothers snorted at that, during a brief moment of consciousness. A circle can be made with two sticks and piece of string. Stick a stake in the ground. Tie the string to the second stick and extend the string and walk about the perimeter. The footprints describe a circle. Voilà! A circle. Then there are round stones and logs, and….

Still this is a good set-up. It has basic credibility, an element of mystery, attractive leads. and the promise of more to come. The pace is good at the start; the cinematography is crisp. That is the first third of the run-time.

But wait, wifey goes all wifey. She is a zealot and fears all this science might disorder the Lord’s work. She goes on and on. Science destroys. Prayer is good. Though we never see her doing anything Christian, like shut up and do good works, give away some of the luxury furnishings in their home, teach their children to offer hospitality to visitors, or any of that boring stuff. Rather she fulminates. (Another case this is where the actor ought to have punched the lights out of the screen writers, John L. Balderston and Anthony Veiller.)

Still she wants to send truckloads of prayers to hurricane victims and not desalination planets, vaccines, or MRI machines, and trained up doctors. For this, by the way, she is much praised in the half-witted remarks on You Tube. So much for the longterm salutary effects of free public education.

Peter puts his Jim Bakker wife into her box, and continues talking to the Martians. Which one is the nutcase?

In a parallel plot the Russkies are also trying to dial up Mars. Red Planet Mars, right? It must be Red. (Get it, Mortimer?) No luck. Their vacuum tubes are leaky, just good enough to listen in on Peter’s transmissions. Some Russian is spoken though the chief villain is Michael Anthony, later of fame on television, who speaks only nasty.

The NBN connection to Mars clears and Peter get the skinny on Mars from his unnamed correspondent. Mars is Eden. There is no scarcity. No disease. Obama-care for all. No bad stuff at all. Not a single Republican on the planet. Everything is free. Everything is good. It is an all-over Donna Reed Show world. Average life span is three hundred years. (Think about sitting through strata meetings for three hundred, that is, 3 0 0, years while Mr. Numnuts bangs on about the drain pipes.) But not a word about those canals or the ice cap.

News of this paradise gets out and hits the spinning headlines around the world. Realisation that Mars is so well off depresses everyone on Earth in a kind of reverse of schadenfreude and they stop consuming, working, earning, start phoning in sick, altogether which makes the world economy crash and society begin to collapse.

How come the Martians are so well off, asks Blondie? Well, they follow the words of the Lord to the last detail. Yep the little green man from the Red Planet starts spouting the King James translation of the New Testament. No copyright?

This news heartens the god-fearing Westerners, and does-in the Earth Reds. The Soviet peoples rise up and overthrow the Commies. Bye, bye Michael Anthony. The Patriarch puts Vladimir Putin in the big chair and he in turn puts the Twit-in-chief in the Oval Office.

At this point the Hallelujah Chorus should have cut it, but there are few more twists and turns. They just do not know when to quit, these people. Fortunately, I do.

Why the good news about Mars should depress people and lead to social, economic, and political collapse in the West is anyone’s guess. Likewise, why this news should arouse the Soviet populace is another guess. After all, if they needed scientific evidence via that radio to uphold their faith, well then, it is not faith now is it?

All of this is presented with a straight face. God is a Martian! He is a Red from the Red Planet. See title. And like all Martians he is a little green man. Tricky as a Red could be, hiding behind that green look. Lyndon LaRouche is right the Green movement is Red at heart! Mars, the symbol of war and blood, is E D E N. Is there an NRA message in this? (Don’t know this Lyndon? Keep it that way.)

No wonder the half-wits commenting on You Tube love it. Still less, do any of them understand the liberation rhetoric of the King James edition of the New Testament, but they wax enthusiastic in the self-imposed dark.

Janne Wass says on the blog Scifist that the original stage play from a generation earlier used the religious card for laughs, but when the playwright tarted it up for the cinema in the frigid atmosphere of the Cold War, it went all serious, solemn, and sanctimonious, a cynical judgement of the audience in 1952 and one that continues to payoff. It is impossible to underestimate some things. It was during the Korean War and the HUAC rampage for those who were not born and have no brain.

‘The Wizard of Mars’ (1965)

From IMDB 3.4 / 359, 1 hour and 18 minutes

In far distant 1975 four astronauts are Mars-bound when they check in with Earth control. Everything is AOK. We knew that would not last. It didn’t. No sooner did Deep Voice hang up the phone, then strange things began to happen.

The plan had been to orbit Mars once, gathering data by scans, ogling, and pressing buttons, when the ship began to shutter and shake. Was it a meteor strike? Meteors are always on hand during space flight films. Was it some force from Mars? Had the lease expired on the ship? Was not it built by the low bidder?

The crew is four, along with Deep Voice, for whom this is the single credit in the IMDB, there is Goofy Charlie, Doc, and Whiner. The dialogue goes like this, repeatedly: ‘I dunno,’ Deep Voice. ‘Let’s find out,’ Goofy Charlie. ‘I’m scared,’ Whiney. ‘Let’s study it,’ Doc. This four-cornered exchange occurs enough times to send me to the crossword puzzle. Deep Voice never knows anything, making him the perfect McKinsey manager, having no encumbrance of knowledge. Charlie is always ready to leap into confusion. Doc wants more data before moving.

Whiney is the woman in the crew and she is always scared, when is not afraid, worried, sick, crying, or wailing. Personally I thought she should walk off the set and sock the script writer for sticking her with such a pathetic character. After all she sat on a mountain of combustible liquid rocket fuel to travel a squillion miles through the void of space to get there, and once there she goes all mushy. Really! ‘Sock him, girl,’ we cried!

More generally I considered the question of whether these four were the best the population of the Earth could find for this unique mission. A leader whose big line is ‘Dunno.’ Doc who looks like a Colombian drug lord. All that about study is just cover. Charlie the dolt. Really, this is the A-Team. Next thing a television clown will be US president.

Oh.

When things go wrong the crew has to land on Mars, though the ship, was not designed for that purpose and compromises have to be made. They use the command module as a heat shield and retreat to the landing pod. They jettison the module and bump, bump, bump, they land on Mars!

Doc wants to wait in the pod for rescue, estimated at four months. Whew, did he bring that much deodorant? (Well, it is a fair question.) Whiney also wants to sit tight and be scared, but Dunno Deep Voice wants to find the remains of the command module and salvage the radio and his PlayStation from it. Using the radio they can pinpoint their location (if by some miracle they can figure it out) and he can pass the time with the PlayStation. ‘Let’s,’ says Charlie, again, and again. My brief hope that they might jettison him went for naught.

Since he has a deep voice, the others agree with Dunno. They don their space suits, for once not those from ‘Destination Moon’ (1950) which must have disintegrated from repeated use under bright lights, and sally forth. Whiney goes on about water, food, nail polish, while silently cursing the script writer. Doc constantly falls behind studying sand, rock, paper, scissors, whatever. Charlie bounds around like a puppy off the leash. Whiney…. well,… Dunno still doesn’t.

For the next thirty minutes or more they traverse Mars. They are awed by it, fascinated by it, wary of it, and thrilled to be the first Earthlings to see it.

What a change of pace from Mars movies up to this time, when most Earthlings on Mars, just want to go home. Though ‘Rocketship X-M’ (1950) has some splendid imagery of a mysterious sepia toned Mars, none of the intrepid adventurers seem to notice, while in other films the explorers do no exploring whatever. In this respect, ‘The Wizard of Mars’ is superior in its effort to present Mars as unknown, mysterious, different, and so on.

The science may be whacky but at least it tries to present a brave new world.

That the only creature in the feature is a PVC alligator is down to the materials at hand. Though the creature high point has to be the Ferengi under glass with a transparent skull for a dome in the city they discover.

Yes, they discover a city by following, I am not making this up, a yellow brick road to the castle on a hill. The Wicked Witch was out but the Ferengi was in. (If you don’t know ‘Ferengi,’ get a life! Or ask The Google, as we were once advised to do.)

Regrettably the Ferengi with the glowing dome merely points the way, and bows out. Too bad because though he had been dead for eons, he showed more life than the Wizard to follow.

The Wizard is the head of John Carradine projected against a field of stars mouthing a ridiculous but lengthy speech about space (vast), time (long), and Visa card payments (overdue). He went on and on, and I began to pine for the thirty minute trek across the sands of Mars, which sands by the way, were white and not red, because it was filmed in Great Basin National Park in Nevada where red sand is scarce. Most of the time during this rant he is out of focus and that helps endure it.

Finally he comes to a point. (He must have been paid by the word, though pretty clearly this is one take and his contribution to the film is this ramble.) If these strangers (I’ll say) will just adjust the universal symbol of time, he will – Hey, presto! – power their rocket ship back to Earth. It seems his watch has stopped and he has forgotten how to set it. Just like my granny.

Charlie says, ‘Let’s.’ Deep Voice, ‘Dunno.’ ‘Let’s study it,’ Doc. And, inevitably, ‘My watch has stopped,’ Ms Whiney. (She really should have socked the writer. Though it should be noted she is not harassed by the men in the crew.) Turns out easy enough. The Universal Symbol of time is a pendulum. Remember that, class. Charlie adjusts it by replacing the rock crystal with the city within. Don’t ask.

Whuska! Off they go back on board the space ship, checking in with ground control for re-entry, only two minutes after their last check-in! Two minutes! What? Was it all a dream? The laundry suggests otherwise but these four are puzzled. Look at yourselves! Their clothes look lived in, torn, dirty, and rumpled. Moreover, and conclusively, wee Charlie has grown a dirty upper lip for Movember. The script writer and director have overlooked this obvious and visible evidence.

This opus has had other titles. including ‘Horrors of the Red Planet’ and ‘Alien Massacre.’ Neither is accurate but the marketing department prefers alternative facts. It has also been re-cut hither and thither to make a silk purse out of it. No go.

A word on John Carradine (1908-1988), the man who pursued a triple career. He appeared in many classic A-features like ‘Stagecoach’ (1939), ‘The Grapes of Wraith’ (1940), ‘The Last Hurrah’ (1958), ‘The Man who shot Liberty Valance’ (1962), ‘Cheyenne Autumn’ (1964), working with some of the greatest stars and directors in the Hollywood firmament. This is by no means a complete list.

In parallel he also was also a guest star in every television series of the epoch, ‘Gunsmoke.’ ‘Perry Mason, ‘Mr Ed,’ and so on and on and on. Though not, I noticed, in ‘My Favorite Martian.’

But by night he also appeared in such cinematographic works as ‘Captive Wild Women’ (1943), ‘Revenge of the Zombies’ (1943), ‘The Mummy’s Ghost’ (1944), ‘Half Human’ (1958), ‘Invasion of the Animal People’ (1959), ‘Curse of the Stone Hand’ (1964), ‘House of the Black Death’ (1965), ‘Blood of Ghastly Horror’(1967), ‘Vampire Hookers’ (1978), ‘Evil Spawn’ (1987), and ‘Buried Alive’ (1990), which fittingly appeared two years after his death and that was not his last credit for he died on set. This is by no means a complete list. It would seem, he never said ‘No’ to a part.

The script writer’s previous major work is listed as ‘Monsters Crash the Pajama Party,’ which was never produced. Sighs of gratitude were hears around the room at that news.

Perhaps it was best that the print I watched was smeared. Then again, perhaps, it was made that way. Per Wikipedia it was made using an optical printer for special effects and was filmed for $33,000. A glance at the cast and crew on IMDB suggests none of them had a prior or subsequent career in the dream factory. Still the space suits looked good, and the desert trudge was noteworthy, if boring.