I have read three very large biographies of Napoleon and found myself none the wiser. They were records of events with little or no insight into the making of the man in his youth, what drove him ever onward in maturity, or the talents that enabled him to do what he did.

There are more biographies of the Corsican than can be counted. Which to choose? No point in re-reading the three I had already been through, so I went shopping! I chose this one because the description emphasised the evidence the author used, i.e., contemporary letters, diaries, and reports, as well as Napoleon’s own letters, essays, and manuscripts. In anticipation of travel, I loaded the Kindle with this 890 page tome.

Indeed, the book opens with an impressive critique of the primary sources that have influenced many other biographies by showing that some accounts by Napoleon’s contemporaries and associates were written… forty-years after the fact, by the grandson and not the principal, based on nothing but memories of an eighty year old who did not keep a diary, produced by a fraudster and not by the man named on the cover, or comprehensively changed in translation by demonising Napoleon to suit English readers. Many memoirs of his contemporaries were very unreliable.

While I cannot judge the veracity of these assertions, they did convince me that this author is interested in evidence more than malice or gossip, which marred the earlier biographies I read.

Here are some of the things I learned.

1.The primacy of the family, a residue of Corsica where it was us-against-all. He stuck with his family members long after they proved to be liabilities.

2. His earlier aptitude for mathematics got him into military school and then the artillery. He long retained that analytic approach to his thinking.

3.His varied but indifferent early service in the Royal and then Revolutionary Army.

4.His decided to be French, and not Italian, or even Corsican. He spoke French badly and wrote it worse.

5.When the Revolution and the Terrors came each thinned the ranks of the officer corps leaving plenty scope for advancement for an energetic officer like the young Napoleon. Energy is one theme. He did sleep seven hours in a twenty-four but seldom in one stretch. He often dictated letters or travelled at 3 am.

6.He spend two years on assignment at the topographic office of the French Army in Paris, which was the de facto General Staff, where four old, experienced, and successful generals war gamed old battles and fictional ones, too, while Napoleon looked and learned. He had a prodigious memory. Thereafter he always collected and compiled maps.

7.In his first field command he created the post of Chief of Staff to manage the stage machinery of logistics and continued that ever after. The result was that his armies had greater mobility than his opponents because they had better staff work.

8.As commander of the fifth-rate French Army of Italy at twenty-six he encountered and bested three Austrian armies, each commanded by generals over seventy. They thought slower, moved slower, had more cumbersome ties to the political leadership, than Napoleon who acted first and explained later.

9.He acted in excess of his orders on the gamble that success would exonerate him, and it did.

10.While the political leadership did not trust any successful general, it needed the money he harvested in Italy and so kept him in service.

11.He filled his reports to the Directory in Paris with (A) exaggerations of his victories which went unchallenged as long as he sent along with them gold and loot and (B) misinformation about the Austrian generals he faced, praising the incompetents and deprecating the able, on the assumption that Austrian spies would read them and that Vienna would then keep the fools in command and replace the able. He continued to practice disinformation of several kinds on all of his campaigns.

12.He developed diamond manoeuvres, which I do not fathom, to allow his troops to adjust to line or column on the battlefield with ease. The innovative formations and rigorous training made his armies superior men-for-man.

The honey bee was his emblem.

The honey bee was his emblem.

13.It is unlikely that he ever said that an army marches on its stomach but he knew it marched on its feet and spent a great deal of time and effort in getting boots for the troops. More than once, the terms of surrender he dictated to a defeated opponent involved shoe leather.

14.He published army newspapers to circulate among the troops which told them why they were fighting, both to defeat predatory enemies and to spread the enlightenment of the Revolution, and praised their deeds. The troops sent these cuttings home to show relatives how important they were.

15.To raise morale he awarded recognition to regiments, usually a motto, which was then sewn on the flag of the regiment. He created other honours and awards to stimulate patriotism and unity.

16.Made himself available to hear petitions from individual soldiers, and was generally very lenient with them while being stern, harsh, and demanding with officers, especially generals. There are some remarkable accounts of him striking up conversations with soldiers on sentry duty, wounded on battlefields, and other common soldiers. The author is sure no other general, not even in the French army, let alone in the Russian, Prussian, Austrian, or English armies of the time, would ever even recognise a man in the ranks. Once he met a solider he would remember him the next time.

17.He devoted resources and time to medical care for the wounded, and later pensions for widows, and payments to the incapacitated. Another theme in peace terms was medicine for his wounded.

18.As First Consul he stopped the bloodletting of the Revolution, invited home emigres, aristocrats, released from prison all political prisoners, and asked exiles to return to France. He appointed overt homosexuals to government posts, as well as Jews, Protestants, and atheists. Loyalty to France and then to himself, these were all that mattered.

19. He imposed Enlightenment rationality and universality to weights and measures, made French the official language rather than Occitan, Catalan, Basque, Breton, Norman, Italian in Nice, Dutch in Dunkirk, German in Alsace.

20.The Code Napoleon revolutionised, simplified, and rationalised the law, reducing the law from 5000 pages to 55 pages of principles.

21.He created scientific institutes and libraries some of which are still in use today.

22.He was a one-man Enlightenment for France in his early years with colossal energy.

23. Most fascinating to me was his ability to switch from one subject to another without a pause. While riding onto the field at the battle at Auerstadt he dictated a memorandum about building a girls’ school in Paris. There are lot of examples of this micro-management in the midst of battles.

24. His greatest military success was the bloodless battle at Ülm, where by a combination of speed, deception, and training his army completely surrounded a larger Austrian army which then surrendered. It was an astounding event.

25.He never understand the first thing about ships, oceans, navies. Indeed, he was convinced, and no amount of explanation could change his mind on this point, that the English naval blockade of Napoleonic Europe weakened England.

26.He found the coalitions he faced were divided by language, by goals, by opinions, even by calendars (Julian or Gregorian), munitions (calibers differed), formations, and so on. Each was a weakness which he — the single mind — exploited while they bickered and passed blame back and forth.

27.Personally he was courteous, calm, and heard out criticisms and alternative points of view. Not the raging tyrant of British propaganda. Though assassination attempts made him ever more paranoid.

28.The destructive invasion of Russia was precipitated by Russian complicity with England to break Napoleon’s continental system, despite a treaty affirming Russian compliance with it.

29.Napoleon’s plan was a month long campaign with battles on the border of Russia, and then a peace. Thereafter, step-by-step he went further in and then tarried. Long before General Winter struck, even more devastating was General Typhus.

30.The enormous army he took differed from the others he had led to success. First and foremost it was bigger than anything he had commanded before with attendant complications of logistics, communications, and movement. Moreover, the garrisons in the Napoleonic Empire from Portugal to the Danube absorbed 400,000+ troops. To staff the invasion army of 600,000+ he depended on contribution from seventeen allies: Bavaria Württemberg, Baden, Saxony, Hesse, Holland, Brabant, Spain, Basques, Catalonia, Poland, Hungary, Mamluks, Arabs, Romans, Milanese, Lombards, Naples, Slovenes, Swiss, and so and on. Altogether they offered a cacophony of languages, uniforms, procedures, calibers, food preferences, and motivations. About half of the invasion army were mercenaries, i.e., not French. It was divided by language and many of the troops from client states were not motivated.

31.Much of his earlier success sprang from the unity of command, the identity of training and weapons, and the speed of his army which he motivated with patriotism. In addition,nearly all of the generals he had opposed before Russia had been septuagenarians who had to get permission from a political leader before moving. This time the Russian Tsar was with his army and many of his generals were in their 40s.

32.His evolution into an emperor and a dynasty was partly to provide continuity and stability. When Alexander the Great died there was no successor and the result was civil war, ditto Caesar. He had also seen popular governments in French itself and in England pulled this way and that by tides of opinion. A monarchy would arise above those divisions provided it was constrained by a constitution. It sounds very like Georg Hegel’s account of a German constitution. Of course, it all rests on the assumption that Napoleon, Junior would be competent.

33. He seldom drank wine and did not drink Napoleon Brandy.

Andrew Roberts

Andrew Roberts

There is much more to the story of this giant, but perhaps this suffices to indicate what a reader will find. At the end Roberts concludes that Napoleon was indeed deserving of the title Great.

Category: Leadership

‘The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney’ (2007) by Michael Barrier

Walt Disney was born in a small railroad town in Missouri. It was a water stop for trains, and he retained a lifelong fascination with trains which led to Disneyland.

He was a bright and industrious young man who had seen too much farm work as a boy to want to be a farmer. In his desire to escape the physical drudgery of farming he is akin to Huey Long.

His distinction in the early animated cartoons was the effort to put emotion into the toons. Whereas rivals like ‘Tom & Jerry’ or ‘Felix the Cat’ were drawings whose heads exploded and then re-assembled, Disney started putting puzzled or hurt expressions on the face of Mickey Mouse.

Walt Disney never stood still. He went from one project to another. He was a workaholic and worked late into the night, even when he was the proprietor of Disney Studios, he was frequently alone in the Studios at midnight.

He was also an innovator and a demon for ever higher quality in drawing, animation, movement, colour, and more. Innovation and quality meant that animators wanted to work for him, and many left higher paying jobs to work at Disney Studios to learn more of the trade. One of his innovations was staff development, as we would call it today. The author also credits Disney with the concept of the storyboard, now used in every movies industry in the world.

He could be volatile. There are many claims that he was tyrant or a racist but this author finds no evidence for either claim. Though the swings of business meant that at times, loyal and able staff had to be dismissed because there was no money to pay them. He was categorically anti-union and paternalistic as an employer. He equated unions with communism as did too many others during the early days of the Cold War, and he was a friendly witness before HUAC. Yuk!

Despite the temptations of Hollywood he was ever loyal to his wife. The author implies that Disney broke profitable business relations with some actors and directors whom he thought, perhaps wrongly, did not treat her with respect. After their first child she had several miscarriages and that led them to adopt a second child.

His brother Roy ran the business side, but always deferred to Walt’s creativity. When Walt used company money to build a scale model train as a hobby, Roy did point out that the stockholders would not accept that. To justify the scale railroad it became a company project, and led to Disneyland.

Roy Disney

Roy Disney

Disney visited many amusement parks and found that those aimed at children bored adults and those aimed at adults bored children. In both cases the boredom meant a short visit. By combining amusements for both adults and children, the visits would be longer, and patrons would spend more money. To facilitate longer visits and more spending, Disney introduced suff development to train guides, operators, vendors in dealing with customers. Another Disney innovation is queue management.

I was surprised to learn how fragile the Disney empire was even in 1960s when it seemed to be an American institution second only to the White House. Since Walt was always pushing ahead to another project – more and better cartoons, television, movies, Disneyland, Disneyworld, EPCOT (which is not mentioned in this book), the finances were always stretched. One sign of this is that the brothers Walt and Roy lived modestly compared to the Hollywood standard of the time.

‘Snow White’ (1937) made mint and set a standard that he never equaled. The single-minded determination to make a feature length cartoon, and to make it an artistic and commercial success is one of the most interesting episodes in the book. The banal description of ‘Snow White’ on the InterNet Movie Database belies what a groundbreaking work it was in 1937.

Disney set out to top that with ‘Fanastia’ (1940) but the technical problems were so great that this project devoured money, and in the desperation to get a product and some financial return, it was neither an artistic nor commercial success. Disney did not always get it right.

Disney made the transition from cartoons to live action films thanks to World War II. When the war began the Department of Defense contracted Disney Studios to make training films, which were at first technical, involving a lot of diagrams and animation, but came to involve actors showing how to repair an engine, or repair a tank tread.

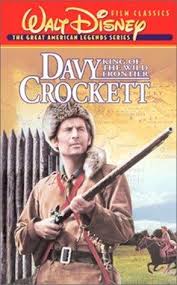

‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ (1954) and ‘Davy Crockett’ (1955) both made money and attracted acclaim. Genius as he might have been, Disney did not follow-up either successfully. He was always reluctant to hire expensive Hollywood directors and actors and ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ is the only time he did. When ‘Davy Crockett’ made even more money, he decided he did not need high priced talent. I do remember that cap!

He seems to have misunderstood the success of ‘Davy Crockett’ because he then cast its star Fess Parker in a series of duds. They were duds because, in effect, Parker was cast as a supporting actors to, by turns, a group of children, a dog, and a bear. When his contract came up for re-newal, Parker quit.

By the way, he picked Parker out of the film ‘The Thing’ (1951), and as an unknown, Parker came cheap.

The 1950s and 1960s television series of Disney was designed to promote Disneyland.

There was a lot of office politics in Disney Studios. Getting his attention was key but he had so many projects going, including constantly rebuilding and expanding the studio that his attention was scarce.

He travelled a lot in the States but also in Europe. The honours and awards poured in but he remained restless for the next project.

There is a good deal in the book about the technical aspects of animation. More than I expected in a ‘Life.’

MIchael Barrier

MIchael Barrier

Michael Barrier played Lieutenant De Salle in Star Trek, the Original Series episode ‘Memory Alpha.’

De Salle

De Salle

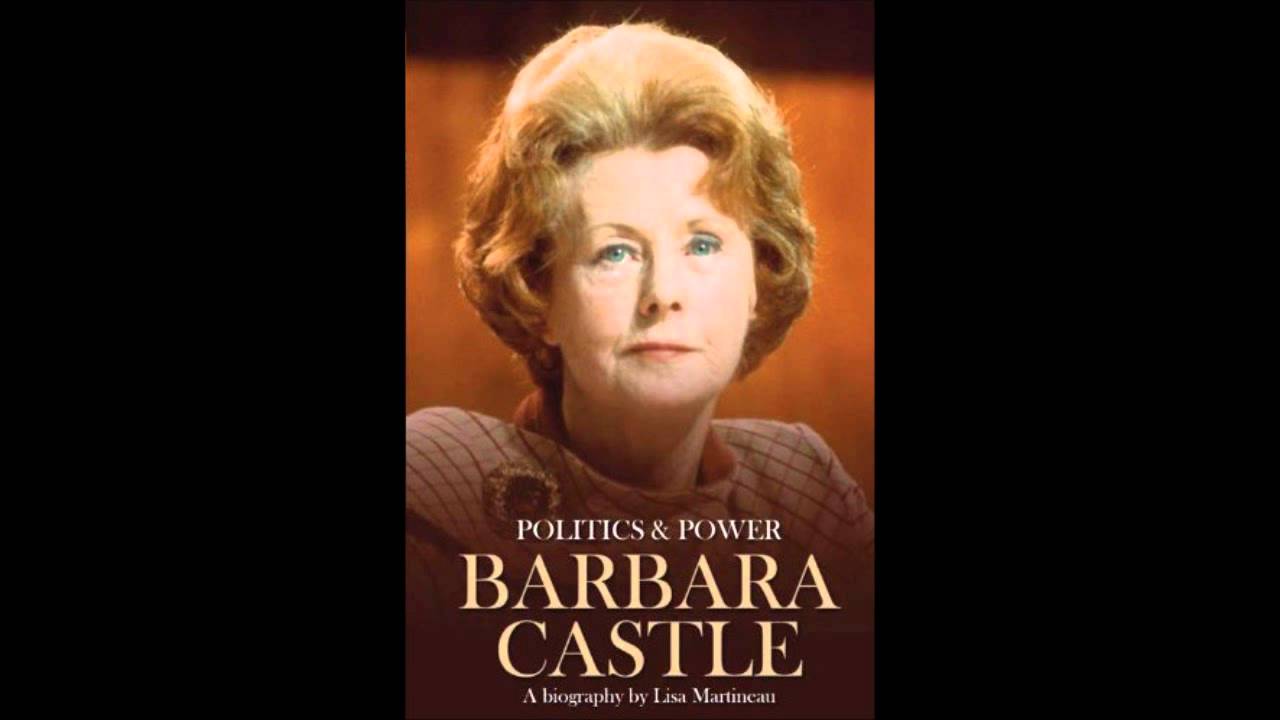

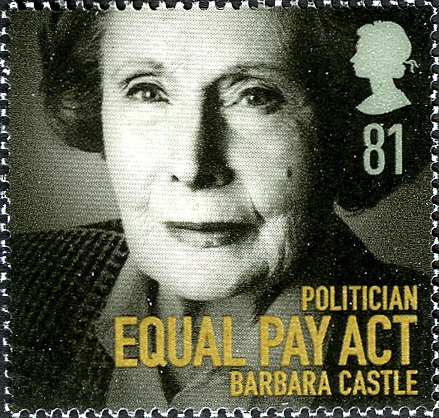

The Red Queen: Barbara Castle

Reader, a test before we begin. Did you ride in an automobile today? Did you wear a seat belt?

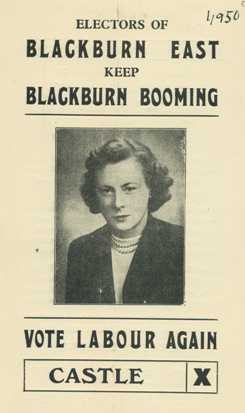

If so, then you owe something to Barbara Castle neé Betts (1910-2002) who was a Labour Party stalwart for two generations. She radiated conviction, energy, and determination. The Red Squire Stafford Cripps said in the 1940s she was a prime minister to be, but that was not to be. By the way, Cripps was not an easy man to impress for he had few good words for several others who did become prime minister.

By Lisa Martineau in 2011.

By Lisa Martineau in 2011.

She was lefter than thou yet from a public school, Oxford, and championed radical causes in the 1930s. That together with her red hair invited the sobriquet ‘The Red Queen.’ A title she accepted with pride.

Her achievements were great and small, from securing a ladies’ toilet near the chamber of the House of Commons, a feat other women had been unable to perform. It was, inevitably, called Barbara’s Castle. She also led the charge against turnstiles on public toilets for women, starting with House of Commons. There were no turnstiles on mens’ toilets, yet they were not pregnant, towing children, or carrying shopping. Of course, Margaret Thatcher fixed all that gender inequality by doing away with free public toilets, making it pay if you want to go.

At the other end of the continuum, she was a founder of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and a tireless exponent of the New Jerusalem that Socialism undiluted offered. She worked just as hard to speed British exit from the fifty-seven colonies it held in 1945. To that end she travelled to many of them, particularly in Africa. I rather suspect the parliamentarian played by Flora Robson in the film ‘Guns of Batasi’ (1964) was inspired by her. By the way, Richard Attenborough is electric in this film.

With the flaming red hair, blue eyes, and resonant voice that emerged from this petite woman, she was spellbinder at the podium. Even lifelong enemies like Hugh Gaitskell said he found himself nodding when she argued cases he opposed.

As a minister of the crown she had a deadly eye for detail and put in nineteen hour days and expected the same from the public servants. When they could not, or would not, match her pace she hired private consultants to add to the workforce. One of her great achievement as a minister in four departments was to hire economists. Hard though it is to believe but the ministries of Overseas Aid, Transport, and Health employed no economists until she arrived. Much as the Sir Humphrey’s of the day disliked her, they found her to be a champion for the department unlike any other minister. As one cabinet colleague, and later prime minister, James Callaghan, another lifelong enemy, said, she simply would not shut up until she got her way, and she often got her way because it was the only way to shut her up. Even in times of declining budgets she always boosted the allocation to her department by brow-beating cabinet and won most of the border disputes with other departments.

There is much to like and to admire in Barbara Castle. It is also true that she was completely one-eyed: Socialism was a planned economy, nay, a planned society. Socialism will give people what is good for them whether they want it or not, whether they think it is good or not. There is a zealot there for whom the problem may require that the people be re-educated. She had no patience, no toleration for those who did not accept her vision of the planned society. Guess who would be the planner in chief.

She detested the sewer socialist in her party in the 1940s and 1950s. ‘Sewer Socialist’ were those who wanted and accepted small gains, like clean water, a working sewer system, modest wage increases, affordable housing, industry pension funds… These incremental changes she dismissed as distractions from the larger, main game of social (r)evolution. When Clement Atlee staked his Party on the National Health Service, she thought it was trivial, and said so. The whole of the planned society had to come first before any of its parts.

When she visited the Soviet Union in 1937 it was the Light on the Hill, and she said so forever thereafter. She was not the only intellectual who saw what she wanted to see in the USSR in the 1930s, see Paul Hollander ‘Political Pilgrims’ (1997), but, while many others recanted, admitting their errors, she never did. Indeed in the 1970s she was still defending the paeans of praise she had sung to Comrade Stalin in justifying the Show Trials. While she advocated abortion in Great Britain, when Stalin outlawed it in the USSR, she rushed to the typewriter to justify his action and extol his wisdom.

Successive Labour Party leaders from Clement Atlee, Hugh Gaitskell, Harold Wilson, Jim Callaghan, Michael Foot,Neil Kinnock, Tony Blair, and Gordon Brown found her a loose canon. She certainly blundered as she steamed ahead, arousing expectations that were impossible to fulfil in constituents, in African nationalist leaders, and in many others. But nothing is accomplished if nothing is tried. She tried, if she was trying. Like Moses Malone, whose recent passing I noted, she had ninth and tenth effort, not just second and third effort.

When she advocated British withdrawal from Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios of Greek Cyprus invited her to Athens for private talks. She was all but forbidden to go by the Party leader, by the Foreign Office, by the Ministry of Defence; she went. The professional diplomats had been unable to find an accommodation in Cyprus for years, but she did it in two weeks. The arrangement that led to the Green Line which still partitions this island emerged from personal intervention.

She did not play by the rules, and that enraged many, even some who were close to her like Harold Wilson.

One of the rules she despised was making deals. She wanted everyone to agree with her, and she asserted her case from first principles, not mutual interest or advantage. Nor would she delay until the timing was more conducive. No way. It was always now or never!

Though the author does not give it emphasis, there is a transformation when she became a cabinet minister. She learned that half a loaf makes a good meal. Compromise today, for tomorrow is another day. As minister of transportation she revolutionised what had been a moribund backwater. In so doing she incurred tsunamis of abuse. She legislated seat belts, breathalysing, speed limits, and other changes that vested interest denounced as a communist plot. The abusive letters, death threats, systematic smear campaigns, jostling on the street, hectoring from the public gallery in the House, she endured from individual motorists who had a god-given right to drive drunk at high speeds, automobile manufacturers who claimed they would be bankrupted by installing seat-belts, publicans, and brewers because breathalysing would and did reduce alcohol consumption. Oh, by the way, her measures also reduced road accidents, deaths, and injuries by 50%.

There was only one way for her, and that was up. She became First Secretary to Cabinet, an archaic title, which made her de facto Deputy Prime Minister to Harold Wilson. She learned to trim, to temporise, to compromise, to balance, to wait for the right time…all those things she denounced in Atlee, Gaitskell, and others in the 1940s, and 1950s. The Tribune group, and later Militant Tendency, in the Labour Party attacked her daily, and she learned what it was like to have marbles underfoot every hour of every day. Some may have seen one of the best political dramas ever, ‘Bill Brand, MP,’ from this time. I say ‘best’ because it got the politics right. In that respect it is comparable to ‘The Sandbaggers.’

Then she moved to labour and took on the Trade Unionarchy that was running much of Britain in the late 1960s. Rivalry between unions took the form of endless demarcation disputes and in effect put the entire county on an unofficial three-day working week (which later became official when the Tories took over). The days lost by strikes in the twelve months before she took over surpassed the total for the previous decade! By now she was less interested in a blueprint for the New Jerusalem and much more interested in sewer socialism, quite literally getting sanitation to work. While Prime Minister Harold Wilson sent her forth, most in the Labour Party opposed any effort to rein in the unions. She was comprehensively undermined, as she had undermined others in earlier years, and failed.

Fail and move up, that is an old adage in Brit politics. She was moved on to take charge of the NHS, rolling up her sleeves started to work reducing private medicine to zero. The doctors resisted, they struck. The winds of hyperbole blew. Once again she played Saint Sebastian, taking the arrows meant for Wilson. She wore away her opponents but the backbiting in cabinet reached new levels. Then Wilson pulled a rabbit out of his hat: He quit. Though she won her battle with the medicos, she was dumped by Wilson’s successor before she could conclude the matter.

She had no future with the new Prime Minister, Callaghan, whose hostility was open; he was a union man first and last, and saw no role for women out of the kitchen. Castle’s effort to legislate for equal pay for equal work for women and then the effort to increase the pay for nurses was anathema to organised labour in the day.

The unions and their bought-and-paid for parliamentarians attacked her even more savagely on equal pay than they had on her earlier effort to sanction illegal strikes. The hate mail, the threats, the denunciations were hysterical. She had to go, and Callaghan dismissed her in his first act after taking the oath while in the car. He did not even wait to get to the office.

She went to the backbench, where she was free to speak her mind. Did she ever! She got herself on every committee in Parliament and the Labour Party and tore into the Labour Government. She reverted to type: Lefter than thou. She hit the typewriter for the newspaper which loved seeing the Labour Party tear itself apart (again). The Tories had only to sit back and watch the fun.

The advent to the European Parliament led her to becoming a Member of the European Parliament where she quickly established a reputation as a demon for detail. She became the leader of the Socialist bloc.

In 1990 she finally accepted a place in the House of Lords, something she has turned down earlier, where she resumed her role as the Socialist conscience of Labour. Age did not weary her, as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown found when she lit into them. She died at her desk, reading legislation line-by-line which always did, looking the mistakes, inconsistencies, slips, and red flags.

The comparison has to be Margaret Thatcher. Ambitious, smart, driven, and similar in complexion and appearance.

Castle was something of a clothes horse, always careful of her appearance, always a man-magnet, with a taste for country houses and French champagne. There were no children. She never learned to drive a car. Her husband Ted, himself a journalist, led the cheering for her. In those days she still performed all the housewifely duties. She ironed, cooked, dusted, often while dictating into a machine.

It also has to be said that she endured the heavy hand, sometimes literally, of the uninhibited sexism of the time and place. Even the newspaper stories from the day make this reader today cringe.

We will not see her like again.

The author does have a distance from the subject, frequently pointing out Castle’s inconsistencies, volte faces, mistakes, and rapacious ego. But at other times it slips into the ‘Barbara could do no wrong’ tone.

For a book about politics there is precious little about the elections, especially in the 1960s and 1970s when she played a major role.

Too often the author shows Labour partisan colours. Calling everyone by the first name meant I got lost among the several Dicks, Jims, and Tonyes. There are some typos. Some broken syntax, well, sentences that even on a second reading did not compute in this reader. Some more editing would have increased its impact and shelf-life. I also wearied from the detail of this meeting and that but perhaps a Brit pol junkie would eat that up.

This detail of events though seems to somehow to obscure the person. Her number one supporter, husband Ted, died, and she kept going, inspired, she said, by Dennis Potter’s ‘The Singing Detective.’

I read this book on Kindle. I do find navigating the bookmarks hit and mostly miss and I have not yet mastered switching to Whisper. The Kindle edition has none of the photographs of the published book.

‘Bolívar: American Liberator’ (2013) by Marie Arana.

What do Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Ecuador. and Bolivia have in common?

Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) was president of each, often simultaneously, sometimes in turn.

Bolívar cropped up in a book about Jeremy Bentham’s crusade to influence events in South America. Bentham corresponded with Bolivar, that is, inundated him with manuscripts, letters, books, telling him what to do. When I read that, I was remind of how little I know about Latin America, and reading a biography of The Liberator seemed a good place to start. Though truck with Bentham made me doubt Bolívar’s judgement.

The first thing to hit me was that when Bolívar was born, the Spanish, including his family, had been in Latin America and the Caribbean for more than 250 years. That is far longer than the European settlement in Australia today.

The first Spanish settlers came on the second and third visits of Columbus a few years after that first landfall on 1492. That was a long time for people to get set in their ways, for the population to grow, for the natural wealth to be plundered, for social structure to map onto the topography, for the bureaucracy of empire from Madrid to develop arthritis, for the local Spanish to resent and yet to defer to distant Madrid. And the distance was measured in months of sea travel which was both uncertain and made dangerous by weather, politics, and pirates of the Caribbean.

Bolívar was born in Caracas in what is now Venezuela to a Creole family of wealth and social distinction. ‘Creole’ in this case refers to those Spanish who were born in Latin America as distinct from ‘Peninsulares’ who were Spaniards born on the Iberian peninsula. This distinction had social, financial, and political dimensions. Peninsulares were of higher status because they were closer to Spain. They escaped many taxes that applied to Creoles. They held appointed offices under the crown denied to Creoles. At one time, such differences might have made sense and might not have been resented but they were unchanged for 250+ years and they chaffed. The more so because those Peninsulares who came were often adventurers, thieves, and incompetents, each bearing a royal license that put them above the law.

The native indian population had either fled the Spanish who remained on the coasts or succumbed to the European diseases that came with them. To labor in the silver and gold mines, and later to work the sugar canes fields, the Spanish imported slaves from West Africa on a large scale and had been doing so for generations when Bolívar was born. Thus were three races mixed and while the sclerotic civil law took little notice of racial distinctions, the Roman Catholic Church did in regulating marriage, registering births, and legitimating inheritances. Racial purity was also a priority to the Creoles in their status war with Peninsulares. There were many varieties of pardos and mulattos, those of mixed race.

Bolívar was widely travelled, through the United States recently after its War of Independence, France shortly after the Revolution, England where he met James Mill, Italy, Spain, and elsewhere. In Spain, such was his family wealth and social status, he sported with Prince Ferdinand who became king during some of the period that followed. He had a tutor who spoke but the rights of man and talked but Rousseau and that ilk. Though Bolívar had no education to speak of, his head was full of ideas in a time when anything seemed possible. Born to a rich family, he never had an occupation of any sort.

A conflict between the reigning Spanish king and his ambitious son, Ferdinand, divided loyalties in Spain. Napoleon entered and placed one of this flunkies on the throne. The several colonies in the New World were even more confused than their brother French colonial officials would be in 1940 with the competing Vichy and Free French governments. Spain had three kings, the old king, his upstart son, and Napoleon’s puppet. In addition there were two rival juntas that each proclaimed the end of the monarchy and the birth of a new Spain. None had much capacity to influence the New World, but its riches were certainly what prompted Napoleon’s intervention, which in turn prompted the Monroe Doctrine in a few years.

There were many reactions among the colonists along the South American coasts as the news made its way to them, reported in English newspapers on American or British ships, since they dominated the seas.

In this confusing time Bolívar wanted both independence from Spain and a social revolution, though I doubt he translated that into the loss of his own fortune, though he did lose it. He was one of the most belligerent of the Creoles, and as efforts at moderation failed, because such capacity as Spain could project was repressive – no negotiation, just mass hangings. Several treaties between local Spanish officials and obstreperous Creoles were violated within the hour of signature, like the treaties the United States made with indians.

One of many films featuring El Liberator

One of many films featuring El Liberator

I have no sense of Bolívar as a soldier. He had no training and his army was at most a few thousand. There are references to him training’s troops but I cannot guess in what he trained them. The terrain between the coastal colonies was forbidding, there being no roads, and simply moving a body of me from one to another was a feat of Hannibal.

He started with seventy men, surprised and routed a slightly larger Spanish garrison, and marched on with two-hundred men. By bluff and some confusion managed to cause another, larger Spanish contingent in a fortress to retire. Again he recruited more men, now at 500-hundred and marched on. This is another of his distinctions. He kept going. When other rebellious leaders scored a victory, they stopped. Not Bolívar. He was now about twenty-seven.

It is a long story with many failures, but Bolívar did not quit and in time learned from mistakes. The first lesson, was that it would be a long road.

Second, that the Latinos would have to do it for themselves. England would not intervene, though it would encourage from time to time to undermine its European enemies. The USA might be a model but it would not intervene either having neither the capacity nor will to do so.

Third, unity was the key to besting the imperialist, unity of the races, Creoles, pardos, mulattos, mestizos, blacks, and indians, and also geographic unity. He saw a single Latin American republic as the future. He opposed slavery and outlawed wherever he went which alienated the Creole slave-owning class of his origin.

Fourth, with a navy the Spanish could, at times, control the coasts, so better to operate from the interior.

Fifth, take allies where they can be found, and one place material support could be found was with the black regime in Haiti.

Sixth, compromise to amass a force. Do not insist on ideological purity from allies. Accept minimum cooperation if that is all there is.

Being a frail human being like all of us, El Liberator did not always follow these rules.

Since all the empires, French, Spanish, and English, constrained trade, the one place in the Southern Hemisphere where free trade was practiced was in Haiti. Several wealthy merchants from the United States had set up there to do business, and the offered funding, investing in future trading opportunities that would result if Spain was divested of its colonies.

Applying these lessons was not easy. Many fainthearted people wanted complete victory by the afternoon, or would quit. Others tried to woo England to no avail. The divisions among the Creoles and the ambiguous role of the Catholic Church, these alone would be enough to flummox most of us, let along crossing racial and geographic boundaries. There were no roads in the interior making movement nearly impossible. For some Creoles who had owned slaves, alliance with Haiti, a regime created when slaves massacred their owners, was impossible, even more impossible that freeing their own slaves.

That seeking of allies also came to mean trying to entice Spanish soldiers to switch sides with promises of citizenship and reward. His wars went on for more than twelve years as he criss-crossed the northern tier of South America in the belief that if the Spanish retained even one insignificant foothold, they would, sooner or later, return in force and subjugate the continent; it had to be a clean-sweep fore and aft. Alpine peaks in the Andes, swamps along the Orinoco, high deserts in Peru, jungle forests in Panama, endless plains, all these had to be traversed with his bedraggled followers. Nature and disease probably killed more than did the Spanish.

Bolivia, Ecuador, Panama, Columbia, Venezuela, and Peru, from these he drove the Spanish. The geography means nothing to me but on a map it is pretty impressive, putting George Washington’s campaigns into the shade.

There were constant conflicts among the locals, some remained loyal to Spain, but even among the anti-Spanish there were many deep divisions, social, racial, religious, regional, and political. Bolívar concluded that three hundred years of Spain’s authoritarian rule left the people incapable of ruling themselves. Though he adopted the forms of popular sovereignty, the governments, such as they were, he created were authoritarian, too. But he seldom stayed anywhere long enough to impose his will; he was always off to the next battle with another Spanish enclave. When he left, the government he had created fell to ruin and conflict.

His armies never exceeded 12,000 and were usually smaller than that. The wheel of death did not seem to phase him in the slightest. Over this period about half of the European population died. Add to that the deaths of blacks and reds and all the shades in between. Many deaths came from diseases for which we now have vaccinations, but even some them trace to the wars when water is contaminated, or populations re-located, or the dead are left unburied. Perhaps 50,000 soldiers died under his command. Of course, that is one battle for Napoleon.

Though the author describes many battles, it is all too much like a game. As far as I could tell Bolívar’s main tactic was to attack head-on. There is little indication he studied the terrain, disposed his forces according to it, tried to understand his opponents’ mind and play to a weakness, as did Robert Lee. Whatever tactical achievements there were, usually came from subordinates who also recruited soldiers of fortune from the demobilised armies of the Napoleonic wars with promises of citizen, land, and wealth. British and French veterans who had fought at Waterloo entered his European legion as comrades. He also bought much war surplus weaponry from Europe after 1815.

The author does a nice job of contrasting Bolívar with San Martin, though she is very clearly of the Bolívar camp. Think I will read about San Martin next to get the rest of the story. Over a 48-hour period they had three private meetings, alone. We know nothing of their discussions, though inferences have been made from the subsequent letters and memoirs of each. Nonetheless, the author writes of these interviews as though present. A license too far, I thought.

For ten years Bolívar fought the Spanish coloniser from Peru to Venezuela and back and forth. When the Spanish finally left, he spent the next ten years trying to hold together Greater Granada, as he called it, consisting of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. As soon as he left one province, as he styled them, the conflict would start. No longer having the Spanish to fight, they fought each other, across provincial, later national, borders, between cities, and within cities.

While El Liberator still lived, Peru had three presidents in one week, the first assassinated upon taking the oath of office, his successor two days later so that third took office on Friday. In combinations of twos and threes the states he created made war on each other and still do.

Once the Spanish oppressor was vanquished, many people saw in Bolívar a would-be king, tyrant, dictator… and opposed his every step. So blind was their automatic reaction — think Fox News here — that they even opposed his efforts to resign, seeing in it a devious tactic to win recall. That makes about as much sense as does Sarah Palin. This opposition continues with the entry in Wikipedia which asserts in its opening paragraph that his aim was to secure personal fiefdoms. No doubt it will be edited by next week.

He died at forty-seven, aged decades beyond the years by the exertions of the soldier’s life. The author estimates he travelled 75,000 miles, most of it on horse or foot in Latin America. At death he was penniless, and outcast by the very people whom he had liberated from Spain, dying in the care of a retired Spanish diplomat in a remote location in Colombia.

In death he has been a reliquary for Latino political leaders to bask in the glory of El Liberator, Simón Bolívar. Whenever a regime wobbles, its president-for-life unveils another statue of El Liberator, most notably and recently the late Hugo Chavez.

Chavez speaks

Chavez speaks

Though no one wanted him alive, Bolívar’s body has been dug up and divided among nations and moved several times, last by the aforementioned Chavez who also took his name for the country as the Bolivarian Socialist Republic of Venezuela. It seems there are no parks or plazas in the northern tier of Latin American without statue of El Liberator from Panama to Bolivia. It does not always work since Swiss hotels are fully occupied by such presidents-for-life.

I mentioned the egregious Jeremy Bentham above and also Montesquieu. One of the interesting themes in this story is whether the laws must be rooted in the society or must the laws be above and apart from the society, and this is a difference between Bentham for whom one-size, his, fits all and Montesquieu for whom the spirit of the laws is the spirit of the people. Intersecting with this argument is one about monarchy. Though Bolívar was unalterably opposed to monarchy, many of his allies and acolytes wanted to recruit a European prince to be king on the grounds that such an outsider, having no history and no loyalty to this faction, region, or race, could defend a constitution against the ebb and flow of local politics. It is an argument Georg Hegel made in his ‘Philosophy of Right’ (1821). That did not work well for Max in Mexico a generation later.

The last chapter is a superb summary of El Liberator’s life and career.

——————-

The book is based on extensive research and is written with panache, and of course, the basic story is both an epic in scale and a saga in duration. I read some of it with the Times of London Atlas open to the relevant page to follow some of the action since most of the place names meant nothing to me.

Marie Arana

Marie Arana

It is also true that the book lapses into hagiography too often for Saint Símon. It labels but does not explain, e.g., when others failed or quit Bolívar succeeded, why? Because he was charismatic comes the answer, which is no answer at all.

Some very strange word choice and some minor historical inaccuracy, e.g., there were no rifles and no artillery. The rifling of the barrels of weapons came later. There were muskets and cannons. It is quite a difference on each side of the barrel. When she writes of ‘riflemen,’ unless she specifically has Chuck Connors in mind, I think she means ‘infantry.’

Annoying overstatements, e,g,, these horsemen were the most audacious in the world. How does she know this. Was there a world horsemen audacity ranking agency?

At times the word choice made me wonder if the author, or translator, was a native English-speaker.

This is the first book I have read from beginning to end on a Kindle. It has taken getting used to, especially for notes and highlights and not losing my place. I started with turning off the public notes and highlights of other readers. No thanks. That is too much like reading a used book marked-up by previous readers. Bad enough reading some of the asinine reviews on Amazon.

Having carried about thirty kilograms of books on our European tour last year, I decided that I would not do that again. The only way to do that is to use a Kindle so I am practicing that before our next jaunt to Turkey in October.

‘Disturber of the Peace: The Life of H. L. Mencken’ (1951 [1986]) by William Manchester

‘Voltaire in Baltimore,’ said one admirer of the iconoclastic H. L. Mencken (1880-1956).

When I moved the copy of ‘The Creed of the Sage of Baltimore’ on my office pin-board a few weeks ago to re-arrange things, I posted it on Facebook. Doing that reminded me I had read William Manchester’s biography of the Sage in 1980. Now seemed a good time re-new acquaintance with this original. Trusty Amazon not only found a copy for me, but also revealed that there had been a second edition which I quickly acquired. To call Mencken an ‘original,’ as Manchester does is right, but it hardly seems enough – unique is better. Love him or hate him or both, he was one of a kind, a singularity.

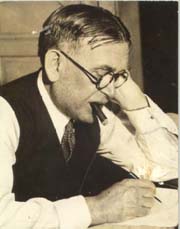

This was a journalist who carried a baseball bat down his pant leg when he went to do interviews, supposing, rightly in some cases, that his questions would provoke physical violence, and he would have to defend himself. This was a newspaper editor who kept a shotgun on his desk when receiving complaints, a near daily occurrence, from members of the public. He would listen but he would not be cowed, that was the silent testimony of the shotgun. If the complainer was cowed, so much the better.

As a boy in the streets of Baltimore, he became fascinated with the machinery in a local shop, as many boys have been fascinated by trains or trucks. The local shop was the neighbourhood weekly newspaper/newsletter. He stood for hours after school watching it. His father gave him a toy printing press and was thus born ‘H. L. Mencken’ when he printed his own business cards with it. He had always gone by the name ‘Harry’ but all the ‘r’ letters in the set had been broken in his first experiments with it, so he styled himself ‘H. L.’ and it stuck.

When he left high school he applied for a job with the ‘Baltimore Herald’ and by persistence made a go of it. He loved the life and went at it like there was no tomorrow. This was a pace he continued for the rest of his life. But the newspaper’s readership fell in a very competitive market, and the desperate editor turned him loose. He was transformed from a journalist reporting events, to a columnist dishing out opinions. Is there nothing sacred? ‘No,’ was his reply.

Sanctimonious clergymen were target practice for his daily column. When they protested in a mass delegation to the newspaper’s owner, Mencken consulted his public and private files. The public files he had collected for sometime, recording incidents of clerical misdeeds with altar-boys, collection boxes, choirgirls, prostitutes, loan sharks, gamblers, you name it. These he recounted with unequaled enthusiasm. Still the clerics protested, so Mencken went to the private files.

Mencken in his prime,

Mencken in his prime,

When he was but a reporter going where he was sent, doing what he told, he was a police reporter, and he was a very sociable drinker with police officers all over Baltimore. They provided him with still more dirt on churchmen that had not yet reached the public record. What a motherlode of gossip and libel did he find, and he did use it, having first mastered the libel laws! The clergy beat retreat, and having won, Mencken did not pursue them. There was still bigger game to hunt in the jungle of the sanctimonious.

Now blooded, he turned to the Baltimore political machine whose Mayor aspired to the spoils of a national office. Once again he published juicy extracts from the public record, connecting the dots, then he turned to the selfsame police officers for more dirt, which was supplied. But even that did not seem enough for so elephantine a target, so Mencken advertised in his column for citizens, in the strictest confidence, to confide in him information about the mayor. They did. Even he was surprised by the rapacious venality thus revealed, but this was a man for Augean stables. He treated it like a baseball game and created a scorecard, with day by day results in the race to the pennant.

His heritage was German, like many others in Baltimore, and he was proud of it. He loved German music and played the piano well on musical evenings with, first, the family, and then drinking buddies. When the Great War started, he saw it as Germany civilising Europe, and if Belgium, France, England got in the way, tough luck! His daily columns, whatever the subject matter, included an encomium to the Kaiser, Germany, mythical Germania, Bach, Nietzsche, or something else explicitly German. As the war went on and American neutrality leaned to Britain, he kept at it. While many Americans of German extraction admired his audacity, they kept their heads down.

His editor hoping to edify and distract him, sent him to Europe to cover the war. Europe? The editor gave him a steamship ticket to Southhampton and train ticket to London. The train ticket was never used. He changed ships at Southhampton for Oslo and then Copenhagen, and then bought his own train ticket to Berlin. Thence he proceeded to file dispatches from the Russian front, extolling German civility, cuisine, beer, courtesy, efficiency, etc. The editor cut off his funds and Mencken returned unrepentant. But seeing the war fervour back home, thereafter he had the wit to keep his own head down, but he never forgave Woodrow Wilson.

Then he turned his talents to editing a literary magazine. He it is that created the house style guide. His was the first to offer this service to contributors. Likewise he also was the first editor to declare what kind of stories he would publish as a guide to authors submitting. Finally, he vowed to treat authors with consideration and courtesy which was not the norm then or now. Submissions were reviewed and returned within 48 hours, and the letters of rejection or acceptance were hammered out on his typewriter. Those rejected got comments on the strong and weak points of the submission sometimes coupled with suggestions of other publications to try, and those accepted were bathed in flattery before he indicated just how little he could pay contributors. Having himself been rejected by editors with curt form letters rather like the disdainful treatment meted out by Qantas cabin staff when I used to fly with that carrier, he was trying to do unto other authors as he wished other editors to do unto to him.

In time he published stories by James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, Edmund Wilson, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Eugene O’Neill (plays in this case) and still more, when no one else would. He also pushed a young Alfred Knopf into publishing.

Perhaps his most lasting personal contribution was ‘The American Language’ which he prepared while staying his pen during the Great War. He was in part inspired to defend Americanese against the British, and their American sycophants, and so it was in part his private war against England in support of Germany. The other inspiration was the black slang he heard in the streets, the saloon talk of polyglot Baltimore, and frontier language of the west which he mostly knew through the works of one of his most beloved writers, Mark Twain. He likened Americanese to a new species of animal, living by its own rules in a new environment, quickly growing away from its origins (Britain). This was a hobby project but when it was published it obtained instant commercial and critical success, though he offended the self-appointed guardians of the King’s English stationed in the United States, and a war of words about words ensued.

HL doing what he did best, editing,

HL doing what he did best, editing,

These guardians should have known better than to take on this master of polemic, venom, and invective. The more so because he had researched the material for many years before assembling it. Ergo, he had it down pat, and he shoved it down the throats of the guardians who assailed him. In time this grew to be a three-volume work, as he tinkered with it for the rest of his life.

The Scopes Monkey trial is well known, and he was the conductor of the orchestra there. He recruited Clarence Darrow for the defence and blackmailed his paper into paying Darrow’s considerable fee.

He fought Prohibition in every way, from brewing his own beer to the pages of the newspapers far and wide and insulted, mocked every dry clergyman, condemned whole swaths of the nation for supporting such idiocy and just would not shut up. This fight gave him an even greater national profile, since many intellectuals, with secure private supplies from bootleggers, did not fight the good fight on this one.

More battles followed. One of his magazines was ‘Banned in Boston’ as was much else at the time, and he let it go, but when the Bostonians started bragging about caging the Beast of Baltimore, what was a man to do, but fight back? He went to Boston Common and sold copies of the offending magazine himself where he was arrested. At the police station he regaled his incarcerators with stories from his days as the police roundsman in Baltimore, while his lawyer did the heavy lifting. The scorecard read: Mencken 1 – Boston Banners – 0. The judge, who had been handpicked by the Banners, found for Mencken, free speech and all that.

When the good citizens of a Maryland Eastern Shore town lynched a negro, dragged from a hospital bed, Mencken fired his heaviest artillery. These great men proved everything he had ever thought about the scum of the earth. Did he go hard! Wallop! When commercial and physical threats against the newspaper and his person rolled in, he redoubled his invective. Crosses were dutifully burned. Dead animals left on his doorstep. All the tricks that are still in the Tea Party playbook were used. Nothing stopped him. He just kept at it until the villains went on to other, softer targets. Remember what I said earlier about the baseball bat and the shotgun.

Alas, Manchester includes none of Mencken nonpareil coverage of presidential nominating conventions and elections. He loved the circus, and democracy offered the biggest and best one for free. He was present at the hung convention in 1924 and must have had a lot to say about that. By the time he covered his last presidential convention in 1948, he was a bigger celebrity than most of the candidates. Journalist crowded around to interview him, while hapless candidates milled around the auditorium talking to each other.

He was an iconoclast who attacked hot air, bunkum, lies, pomposity, pretention, vain-glory, stupidity, ignorance at every turn, and if one attack was good three or four were better. Indeed, his modus operandi became so well known that one well-meaning friend asked him if there was anything he did believe in, and the result was the Sage’s creed.

Manchester offers no summing up of Mencken’s life, legacy, or impact. My own is this. Puncturing balloons is great fun, and there are plenty of hot air balloons around to puncture, and most of them have so little self-knowledge that they do not know that they are full of hot air. In this, as in so much else though, one has to know when to quit, and Mencken did not. He was like a Groucho Marx who just keeps rabbiting on ridiculing all about him, and with age Mencken became far less discerning in the targets he selected. Neither the Great Depression nor the rise of Adolf Hitler could he take seriously and so his star waned. Just as William Jennings Bryan clung to old verities, in his age so did Mencken.

William Manchester

William Manchester

Moreover, Mencken was not wholly negative. He loved baseball his whole life and never said a bad word about it, not even during the Black Sox scandal. He had a blind eye there. Manchester barely mentions the sport but one reason Mencken went to New York City as often as he did was to see Yankee games.

When I visited Baltimore for a conference, I spent far too much time conferring, and did not make it to the Mencken Room, which is only grudgingly open now and again. Likewise I did not do an Edgar Alan Poe homage such was my professional fervour, long since outgrown. I did make it to an Orioles game though! I did go over the submarine in the harbour, and I did see Fort McHenry from the water with a boatload of sozzled conferees.

The second-hand copy Amazon produced is marked up, doing the same myself with most books I read, I sometimes wonder about the marker. Is this someone I would get along with? I try to see some pattern in the mark-up. The marks in this book seem to be analysis of Manchester’s style, his choice of voice — third person past, the mix of description and anecdote, the passive versus active voice. I wonder if the writer was an author. The copperplate penmanship suggests a woman but I have been fooled on that before.

Speaking of marked up texts, as an undergraduate, I had developed a method for selecting used textbooks that worked perfectly.

First I only looked at copies that were highlighted in yellow. Why? Read on and be enlightened. Second I concentrated on those yellow highlighted copies that were densely marked in the opening chapters. Yes, there is a method to this. And remember I was buying in a crowded bookstore with many other students getting books for the semester, so there was physical and social pressure to get on with it.

Ah, the method? I discovered by the end of the freshman year texts that were marked in yellow were used by dolts more interested in the yellow marker than any meaning the text might impart. The yellow highlighter was a novelty in those days and only a few students used them, and they used them, it seemed, more as a status symbol than anything else. Why do I say that? Because the highlighting stopped within a chapter or two. Either the reader dropped the course, give up to failure, or relied on copying the work of others. Law One was: A text highlighted in yellow was likely to be clean after a few chapters.

As a corollary to this law, I also noticed that the more densely marked the first chapter was, the sooner the marking stopped. Someone who highlighted every line on page one, had no idea what was important and what was not. Such an indiscriminate marker was destined, know it or not, to drop even sooner than the average Yellow-Head, as I called them to myself. Law Two was: the more frequent the yellow in Chapter One the sooner the highlighting would stop, leaving the remainder of the text untouched.

A few times a friend expressed surprise to see me pick a book that was heavily marked in the opening pages, but I gave a spurious reason, about that marking saving me the work of doing it myself, rather than reveal the two laws above! These I kept to myself until now.

Mencken’s Creed for those too lazy to look it up for themselves. It is sometimes edited to suit the quoter.

I believe that religion, generally speaking, has been a curse to mankind – that its modest and greatly overestimated services on the ethical side have been more than overcome by the damage it has done to clear and honest thinking.

I believe that no discovery of fact, however trivial, can be wholly useless to the race, and that no trumpeting of falsehood, however virtuous in intent, can be anything but vicious.

I believe that all government is evil, in that all government must necessarily make war upon liberty and the democratic form is as bad as any of the other forms.

I believe that the evidence for immortality is no better than the evidence of witches, and deserves no more respect.

I believe in the complete freedom of thought and speech alike for the humblest man and the mightiest, and in the utmost freedom of conduct that is consistent with living in organized society.

I believe in the capacity of man to conquer his world, and to find out what it is made of, and how it is run.

I believe in the reality of progress.

I – But the whole thing, after all, may be put very simply. I believe that it is better to tell the truth than to lie. I believe that it is better to be free than to be a slave. And I believe that it is better to know than be ignorant.