IMDB metadata 1 hour and 7 minutes @ 5.0/10 from 1246 time wasters.

‘The aliens are coming! The alien Russians are coming!’

The lobby card misleads. As usual. There are no zapping flying saucers.

The lobby card misleads. As usual. There are no zapping flying saucers.

The Cold War is very cold and John Carradine, with his cadaverous appearance and other worldly voice, leads the spooks once again.

He was a nuclear scientist who adds sugar to his radium and blows himself up. Sad. His dear friend and colleague ruminates on the morality of atomic weapons in the aftermath with his comely daughter and Igor. B o r i n g.

To liven things up comes the Zombie Carradine, looking even more cadaverous and spooky than ever with the pancake makeup. No, he does want a cup of coffee. He is there to lay down the law. His dead body has been put to work.

This Lazarus is speaking for the otherwise Invisible Invaders (the I-Squares) who live on the Moon, and have done so for squillions of years (without paying a cent of rent). Not even the really big telescope at Mount Palomar that Bruce Bennett used when Carradine was the ‘Cosmic Man’ (reviewed elsewhere on this blog) could see them or their works. They are INVISIBLE. (That is music to the film’s producer because it means no special effects budget is required.)

Indeed the main effect is shuffling foot prints so we know the Zombie alien is coming. It seems the Zombies are invisible, too, well, some of the time but not always. Consistency is not a Zombie virtue.

The budget cutters have been at work on the Moon, and to economise the I-Squares are using the Earth’s dead as Zombies. We are told often in a radio voiceover that there are hordes of them rampaging around killing the living to convert them into Zombies to meet their KPIs, Killing Performance Indicators. Yet we only see six of them, all men in suits with neckties and all of them 1950s whitebread. We see them about six times. It looks like two takes, repeated and repeated, one coming down a slope and one on the flat, all in Bronson Canyon. The property values never recovered from this exercise.

Why do the I-Squares want to depopulate the Earth? Are they anticipating the Solar contamination of Paris Hilton? The fraternity brothers have no idea. Situation normal.

Carradine is not there to negotiate, just to threaten. He tells his ruminating old buddy to call on world leaders to surrender and be quick about it, which his buddy does by going to D.C. to pass the word where he is laughed out of court. The carrion the press join the fun with spinning newspaper headlines. Situation normal.

Though the threat is global we only see the Yankee response. Not just whitebread, but only Yankee whitebread.

‘No more Mr Nice Guy,’ declares an disembodied Carradine (whose body has now gone onto to another gig), and the I-Squares begin inflicting disasters on the world. First, they take ‘I Love Lucy’ off the air and riots follow. Then they cause the New York Yankees to lose the pennant. Can it get any worse?

Yes, Richard Nixon gives speeches. Aaargh! Enough. There is stock footage of fires, floods, and famines that result from Nixonionisms.

Now D.C. responds by throwing all the resources of the mighty Federal government into the problem. These resources are: one ruminating, aged scientist, his assistant Igor, his daughter who bites her knuckles, and John Agar, proving there is no bottom to touch in his career descent. There is also one jeep and a panel van, and one, only one, radiation suit. That’s it. The Boy Scouts were always better prepared for Armageddon than that.

Life on Earth depends on these people!

Life on Earth depends on these people!

This is the Arsenal of Humanity? Blame the budget cutters! Fortunately, they have an in with the script writer. Plus now that Carradine has gone, the Zombies are not only stiff-legged, they are stiff-brained. There is no ethereal voice to scare everyone.

Despite the absence of Whit Bissell from the lab, the aged scientist hits on the killer weapons for the undead dead Zombies whose bodies are inhabited by the spectral I-Squares.

Taking a page from Bissell’s lab manual in ‘Target Earth’ (1954) (reviewed elsewhere on this blog), the aged ruminator prepares a sound ray. (Hey, that is what it is.) It focuses Beach Boys songs onto the Zombies and the ‘Good Vibrations’ are too much for them. They are driven from the cadavers and die. Die, alien, die! The fraternity brothers liked that.

Igor chickens out but recovers. From this episode we know he has no chance with the knuckle-biter. Agar sleepwalks through most of it, and his stunt double in the radiation suit does the heavy lifting. But there is no doubt he got the girl.

While the I-Squares are Reds in invisible disguise, they are so geriatric with all the foot dragging that, well, they would fall over their own feet. If left to roam around they would eventually do themselves in.

The sets are empty. The film editing leaves in much that should have omitted, like the firing range targets in some of the explosion footage. Most of the, er ahem, story is told through radio voiceovers. Always a sign there is no sound technician getting paid. The direction is static, usually a sign of one-take. No one moves once the focus is set, so that it does not need to be pulled again. The screenplay is…. (what is the right word…) absent.

John Carradine must have been working off some gigantic karmic debt in doing all these one and two day gigs in Z grade films. This would have been half a day for an old trouper like him.

John Agar, well, what more can be said. He is another Hollywood high diver. Once a second lead to John Wayne, he fell to these catatonic depths. He is leaden here, no doubt responding to the director’s orders. I have described his descent in another post.

The director is that speed merchant Edward L. Cahn who could turn these things out in five days or less, much loved by producers for getting it in the can. He could do fifteen of these a year, but no one can watch that many in a year, and retain sanity. I could not find a picture of him on the inter-web.

That the IMDbasers give it a 5.0 average irritates, since the better ‘The Cosmic Man’ (1959) is 4.7 where Carradine brings an interplanetary Marshall Plan.

‘The Cosmic Man’ (1959)

Metadata from IMDB: 1 hour and 12 minutes, 4.5/10 from 302 opinionators

A shadowy figure offers world peace and an interplanetary Marshall Plan, while curing a polio-stricken youngster, and in return is then gunned down by men in uniform. Ah, the 1950s when the worlds were so much simpler.

This lobby card wins first prize for irrelevance to the movie it purports to summarise. There is no spectral green figure in a cape, and the insert in the upper right refers to a ten second blur.

This lobby card wins first prize for irrelevance to the movie it purports to summarise. There is no spectral green figure in a cape, and the insert in the upper right refers to a ten second blur.

While it repeats the tropes from many of its Sy Fy genre stablemates there are elements that appeal to viewers over the mental age of the fraternity brothers. (Think of them as part of Channel 7MATE demographic for whom ‘Top Gear’ is high culture.)

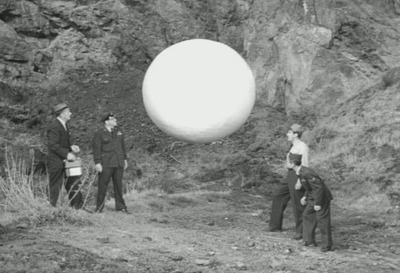

Before the twists, the set up. An orb is found suspended in mid-air in Bronson Canyon, a favourite Hollywood locale where Randolph Scott dealt with many a villain.

It looks like a large golf ball without the dimples.

‘Can’t have that,’ declares Smokey, the park ranger. It might fall on someone. Unbeknownst to millions of visitors to Bronson Canyon there are many secret atomic military bases in the vicinity, and Smokey calls in the police and they call in the uniforms. A Commie plot is suspected in all but word. No one thinks to call Sam Snead, the golf ball expert of the day.

Someone also calls in Herbert Brix, a scientist from Mount Palomar, who is shown driving out of the parking lot of this famous installation, not once but twice, in exactly the same film footage. There are no interiors of the big telescope there.

Thereafter the colonel on the scene and the scientist spar over what to do. The colonel wants to contain, capture, control, crush, cut, and do other manly things to the sphere, which continues harmlessly to hover.

Brix wants to think, to look, to inspect, to test, to speculate, and to do science, perhaps even communicate with the owner of the golf ball.

Brix doing science.

Brix doing science.

‘Thinking! Who has got time for that,’ bellows the colonel! ‘It is a threat!’ (The fraternity brothers have always had their suspicions of golf balls because they always seem to be guided by unseen forces.) But the colonel’s efforts, adumbrated above, are ineffective, so reluctantly he listens to Brix.

Brix surmises from no evidence apart from the script that the golf orb came in peace and is a vehicle and that its passenger has disembarked through the forward, invisible door. The colonel telephones the general, who is too lazy to come and see for himself, for ever more soldiers to find this infiltrator. A cordon bleu is thrown about Bronson Canyon much to the annoyance of Charles who lives there.

The soldiers and more scientists converge on the spot and put up in an inn whose widowed proprietor has a crippled son of, say, ten or eleven. Dad was canceled in the Korean War a few short years earlier and the widow took the payout and bought the inn where she can attend to her boy. It is out of season but now she has a full house. Cha-ching goes the cash register.

Meanwhile, a peeping Tom seems to be about, causing much consternation among the citizenry who pressure the police, who pressure the mayor, who pressures the army which pressures the scientists. Much pressure to Do Something.

With all the coming and going at the inn another fellow shows up, rugged up in an overcoat, a floppy hat, and wearing coke bottle glasses.

What else could he be but a scientist in that regalia.

What else could he be but a scientist in that regalia.

He speaks in the voice of John Carradine. Shiver. He speaks ever so slowly and formally that we know right away he is not of this vernacular. The widowed proprietor mistakes him for another scientist and gives him a room in the back where he can rest. We know he is golfball orb lagged from his travels.

Brix tries to reason with the colonel, and the colonel listens and even rebuts part of Brix’s argument. Nice. Reason.

Enough! Carradine’s two-day contract means he has to hurry up and spill the cosmic beans. When the whole group is gathered in the inn, JC dowses the lights and reveals himself as the Comic Man, the first of the cosmonauts. Yes he uses that last term, which latter became identified with the Soviet space program so he must be a Commie. He warns against nuclear weapons and war, and offers the help of the Cosmonauts in development that will lead to world peace.

He does not exactly reveal his very own self since he is invisible, being from another universe, dimension, bad dream, or something. Or maybe he is the prodigy of the Invisible Man and Invisible Woman as reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

To Brix this message fits with the low key way the Cosmic JC has been going about things. First Contact is always tricky in Sy FY. First the alien has been trying to scout the place, steal some of clothing, and drink some coke to get those glasses.

To the colonel it is Yalta all over again, once more. This peace will be slavery. Better dead than contented! That seems to be his motto.

Meanwhile, JC has taken a liking for the crippled boy who teaches him to play chess. Nice.

Having seen enough, JC prepares to depart. In so doing he takes along the boy! Alien-napped! A hostage! The worst possible interpretations flow fast and furious. The colonel is ready to nuke the place! Better to destroy the boy than lose the boy.

JC puts aside the boy and as he alone approaches the golf ball orb he is blasted by the United State Army! Makes a Twit proud to see one harmless old man chopped down.

In a nice touch, the switch is not thrown by the colonel, but by another scientist called in by the colonel because Brix is such a sissy. This scientist does it, he says, because he want to detain JC. Ah huh. Intentions aside. JC is cooked. He disappears into the dust, and blink, the golf ball orb is gone.

The boy, on his feet, walks to his mother because he is now cured of his disability.

Whew.

It was not clear to this jaundiced viewer if the colonel got the message about the boy, or if he cared.

Nor is it clear what the other cosmonauts will do now that JC is dust. But no one in the script seems worried about that.

Meanwhile, the slow but sure Brix has insinuated himself with widow. The colonel can tell the general he will not have to move.

It is easy to see this tale as social criticism applied to the trigger fingers of all those uniforms. That was risky in those days of Cold War uniform worship.

It is also refreshing in the Sy Fy genre to see a scientist who is not mad and who is not completely ineffectual. The colonel, having seen many other Sy Fy movies supposes Brix is ineffectual because he does not understand what Brix is doing. In fact, his science is what provokes JC into revealing himself and it is mainly to him that JC speaks. This annoys the bristling colonel no end. He and his men try to shoot JC in the dark after hearing this Yalta message.

Generally in Sy Fy, there is no science at all, a mad scientist who started all the trouble, or a bunch of clipboard-carrying do nothing scientists. Brix is none of these.

His brief conversations withe colonel make sense.

One critic speculates the John Carradine must have been working off an enormous karmic debt by taking every part in every bad movie he was offered. He certainly did.

The critics linked to the IMDb page deride the film for its poor special effects. It is after all a magnified gold ball and some claim to see the dimples. The shadowy shots of the invisible Carradine are mostly murk. As a creature feature, it lacks a creature, despite the lobby card above. Moreover, there is little ka-boom to keep the retards happy.

However, its biggest sin on the keyboards of these critics is that it repeats the message of Klaatu from ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still.’ Peace on earth, good will, and harmony for all. ‘Boring,’ cry these critics. ‘Been done,’ they say.

What clots!

There are no original stories. It is how the tale is told that makes it interesting, and this low-key telling with some respect for science and scientists is out of the ordinary. The romantic element does not get in the way of the major plot, whereas in many films that would have been the cause of tension between Brix and the colonel. While the widow does a scream or two, she is mostly window dressing. The tension is about what to do and nothing else. The paraplegic boy is integral to the plot but not a tear-jerker.

That is, the elements are in balance and the focus is always on the main plot. Aristotle would approve.

It is noteworthy how little science there is in many Sy Fy films. The aliens appear and the cast blasts them. Sometimes a lab coated scientist, inevitably Whit Bissell, fine tunes the blaster and bang, that is it. In many, there is no science at all. They are played as mysteries, or thrillers. Period. ‘It Came from Outer Space’ (1953), a personal favourite, has no science in it, after Carlson puts aside his telescope in the first two minutes.

Herbert Brix, ever heard of him? He was an Olympic athlete whose physique led him to play Tarzan in a film serial when John Weissmuller beat him out for the feature film role. Brix liked the life but, unlike many, realised his limitations. He quit and took acting lessons for some time, and then changed his name to leave behind his he-man persona and became Bruce Bennett, and returned to become an accomplished supporting actor. This outing would have been one of his few romantic leads.

He has a easy manner, a slow smile, a reassuring baritone, and fills this bill well. He supported Bogart in ‘Sahara’ (1943), ‘Dark Passage’ (1947), and ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ (1948). He quit a second time and went into real estate in California and did well. He is described on Wikipedia as a recluse who did not attend fan conventions, do interviews, reply to would-be biographers, and such as many retired actors do. He stayed married for sixty-seven years and died at one hundred.

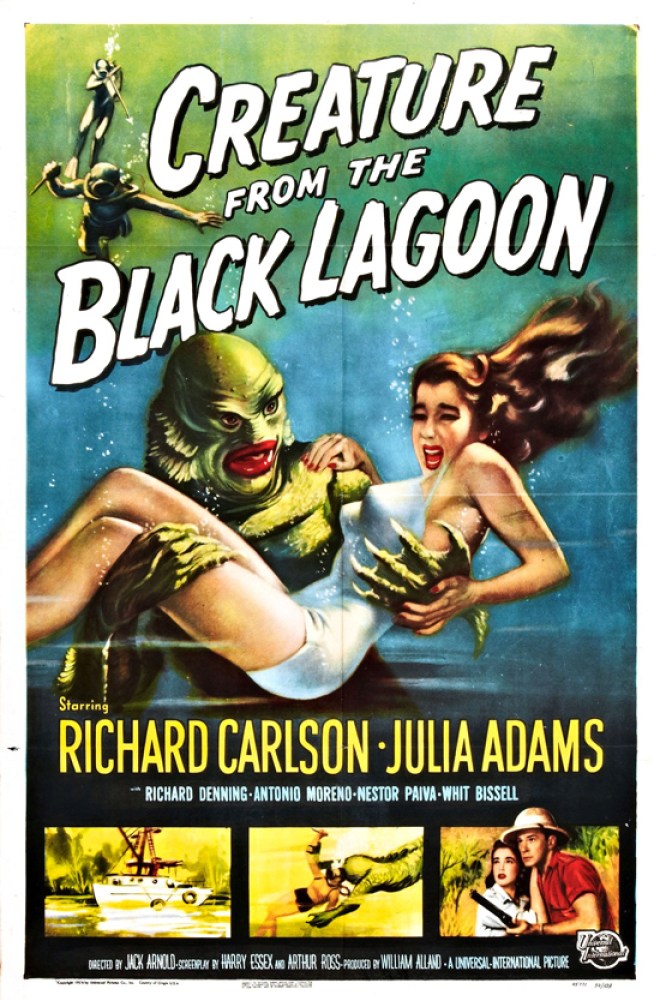

‘Creature from the Black Lagoon’ (1954)

1 hour 19 minutes: 7.0/10 from 20,081

It is a creature feature; it might even THE creature feature, but is it Sy Fy? Janne Wasse includes it on his Scifist because there is much pseudo-science in it about geomorphology, geology, geography, geostuff, topography, evolution, riverine systems, and the like. It is not the usual astronomy and space flight but it is science but there is not a mad scientist in sight.

The title passed into the vernacular two generations ago, understood by people who have never seen the movie and do not want to do so, and it spawned two sequels in an era when such follow-ups were rarer than is today a good film from Big Hollywood. More than 20,000 ratings puts it in the inner circle for such films on the IMDb. The two sequels were ‘Revenge of the Creature’ (1955) and ‘The Creature Walks among Us’ (1956) to be watched only for those who pursue the complete set, say the experts. Note that the sequels each had a distinctive title without a number on the evident assumption that audiences could figure it out. Not so today when numbers guide the prepubescent ticket buyer: Rocky 19, CGI Crap 13.

Here is the set-up. A strange fossilised skeleton is found in the upper reaches of the Amazon River. So strange is it that the Americans on sabbatical leave nearby become interested. These Americans are Richards Carlson and Denning and Julie Adams. Denning is the dean of a research institute, and he is totally preoccupied with funding, whereas Carlson is a rock-chopper, and Julie is the theorist whose work is praised more than once as vital, though we neither see nor hear any of it. To gold plate the Sy Fy credentials they take Whit Bissell, ever a fifth wheel in such capers.

Antonio is the local man who hires the boat and crew. Nestor is the captain and he is ready when the chips fall. Equipped they return to the site of the discovery to find two of Antonio’s men slashed to death, as though a crazed Canberra budget-cutter had got them. Oh, oh.

Well it is a jungle and such things, if distressing, are to be expected so they continue and set a guard. Much sweating in the Jeff Bezos sun follows with no result. Then after seminar gobbledegook, they decide to go further up river into….the Black Lagoon. Nestor. having peeked at the script, is not so sure this is a good idea but the money wins the argument.

With scuba gear there is much arresting underwater photography. However, the highpoint, which every viewer remembers, is the parallel water ballet between the lissom Julie Adams on the surface with a backstroke and….the Creature in depths below mimicking her turns, evolutions, and strokes. These are hormones falling in love with a vision come to his dark, remote world.

We know, by the way, that he slashed the peons earlier but we do not know why, and we never find out.

As Julie disports to wash off the hot day’s toil, she treads water upright to call to a Richard, and the Creature reaches for her foot.

It is delicate, almost shy approach. It tickles her toes and with a start, off she goes.

Julie and Carlson are a couple, very much so, but it is explicit from the near the beginning that they are not married. That was a risqué thing to say in a 1954 movie but there it is. They spend much time…together, when Denning thinks they should be earning his crust. There are words, low key but serious, about KMIs, Key Money Indicators.

Then a guard gets slashed and footprints are found from the Lagoon to the camp. The footprints are of a gigantic….creature!

Denning wants to capture it, seeing headlines and patrons throwing money at the institute. Carlson wants to take pictures of it (with largest iPhone ever seen) and come back with specialists to study this merman, a link to our primordial past, as heralded in the opening voiceover. (Not on the Fundamentalist list of top movies this one since it has much to say about evolution from the seas.) Julie wants to communicate with it but how…? An SMS? Antonio wants to get back for soccer game because Pelé is playing. Nestor wants to get paid. Whit Bissell patiently waits for a cue as supporting actors must.

Then, suddenly, it does not matter what they want. The Creature kills another peon, then after hiring a beaver as a consultant, damns the entrance to the Lagoon. They will have to fight their way out. They do. Denning is fish food, after saving Carlson, who saves Adams from a fate worse than a GOP majority.

The fraternity brothers counted: three missiles from the underwater spearguns stick in the Creature, he was shot three more times by a rifle from a distance, scorched with flaming kerosene, and blasted innumerable times up close by pistols, and still he went on. With skin this thick, he should be the dean.

For its time and setting, it is notable than all the peons had names, and the one who is wounded remains with the crew in the care of Julie, who as a theoretician can give him sips of water which no one else could do. When some of them are killed there is stunned silence and grief on the part of the principals that such nice and helpful chaps got wasted. By contrast in ‘The Snow Creature’ (1954), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, none of Japanese-speaking Nepalese peons have names and their deaths are merely inconvenient, not an occasion for regret and remorse.

Although she is assigned the screaming duties, Julie does pitch in during one crisis with more vigour than 1950s damsels were usually allowed. She had a subsequent long and distinguished acting career, but she is only ever remembered for this role, as she ruefully acknowledged in later life.

Though the discussions are abbreviated, it is also noteworthy that the Creature here is accorded some respect, again unlike ‘The Snow Creature’ (1954) which is treated as a big, huge, lab rat. Divided though they are in intentions, at the outset neither Richard means it any harm, but both want to prove its existence, one for further study and the other to reap publicity that will fund more B movies. Alternatives to bam-bam are aired and debated. Not so in most creature features of the era, where bam-bam is the first and last option as per the Snow Creature.

The Richards are B Sy Fy aristocrats, each with an impressive pedigree.

Spot the Richards.

Spot the Richards.

Carlson is so ordinary that he is everyman, slightly withdrawn, thoughtful, and not an action man, but when action is required, well someone has to suck it up and get it done, and he does.

Denning’s character has a little edge here, which differs from his usual Mr Libra roles. The two of them spend most of their time in their underwear, ah, swimsuits, and it is evident to those with a sympathetic eye that there is gut-sucking going on.

Denning had been on the way up in A films before World War II, but when he returned from three years in the Army he had been surpassed by newer up-and-comers. He could not get any work.

With his GI loan, he and his wife bought a van in which to live and caught and sold lobsters off Long Beach to make a living, while he went to one audition after another, landing a few very small roles. Enough to give him hope of more to come but not enough to eat. One cheque a year is not enough. Evelyn Ankers, a scream queen from B movies, his wife, more or less gave up and concentrated on the lobsters.

By 1948 he had proven himself again: photogenic, compliant, always prepared, responsive to direction, affable, stable, reliable, and helpful if an another hand was needed on the set to do something. He went where the work was for him, to B pictures and made his career there.

The Hollywood Star System of the era had many laws and one the chasm between A and B pictures. The B pictures were made by B picture units and players. A young B picture director, writer, or actor, might rise to A-land and an A actor could slide into B never to return, but there was no free movement back and forth between the two worlds. All tickets were one-way. There was a similar wall between the A-land and television, whereas there was no such block for the B world, which is why as television grew it was populated with those from the B picture world in front of and behind the camera.

As Denning got back into the casting calls, Ankers gave up the lobsters to grace the silver screen once again.

The director was Jack Arnold. His name in the credits is almost always a guarantee of a brisk pace, artistic set-ups, quality camera work, good special effects, and care in establishing the context so that the action makes sense.

None of the actors ever saw the Black Lagoon that viewers see. They did their work in California getting wet in a water tank outside the studio. The Lagoon footage, including the ballet with the Creature and Julie’s body double was shot in Florida.

One critic at the time called it King Kong underwater. The Creature is the last of his kind and he discovers an impossible love that drives him to destroy those who get in his way, and finally to his own destruction. Well, something like that.

It was made in 3-D when that was the fad du jour. Creature features were made in 3-D for a few years, but it died because (1) it was expensive to shoot, about twice ordinary cost, (2) it was then expensive and difficult to project, and (3) only a few effects worked in 3-D.

Reasons (1) and (3) might not have been decisive, but (2) was. To project a 3-D movie in the Rivoli on Second Street in 1954 required two projectors (not one) and Dale McCulloch had to synchronise them to the single individual frame. One frame out of sync and the film became a blur to the audience, four of five out of step was an LSD trip. Moreover the film reels were so large even a modest feature like this had to have an intermission so that the second reels could be loaded and synchronised. The big studio sent technicians around the country to train projectionists, like Dale at the Rivoli, on projecting because it seemed that was the wave the future. Then it waved goodbye.

‘Forbidden Planet’ (1956)

Metadata from IMDb: 1 hour and 29 minutes, 7.7/10 from 37,942 opinionators.

In a flying saucer Earthmen travel by hyperdrive to far Altair sometime after AD 2200. Vroom. Yes, Regina’s own Frank Drebin leads Bart Maverick, Warren Stevens, Comic Relief, and Richard Anderson on a voyage to discover… Anne Francis. That’s the way the fraternity brothers saw it.

Drebin had already had an ‘Appointment on Mars’ (‘Tales from Tomorrow’ [1951]) and he is the honcho.

Lee Tremayne (uncredited) tells us in an opening voiceover that ‘men and women in rocket ships’ were now colonising the stars. But no women are to be seen on the United Planets Cruiser C 57D, nor any dark faces or slanted eyes. The sizeable crew is all whitebread.

Still in 1956 merely to mention women on rockets ships was progressive.

Robbie the Robot, voiced by Marvin Miller (uncredited) of ‘The Millionaire,’ is only upstaged by Francis’s micro skirts. He never carries her around per the lobby card.

Robbie is much too reserved and she is too demur for that. But still when you have never seen a man, maybe a robot is fully functional.

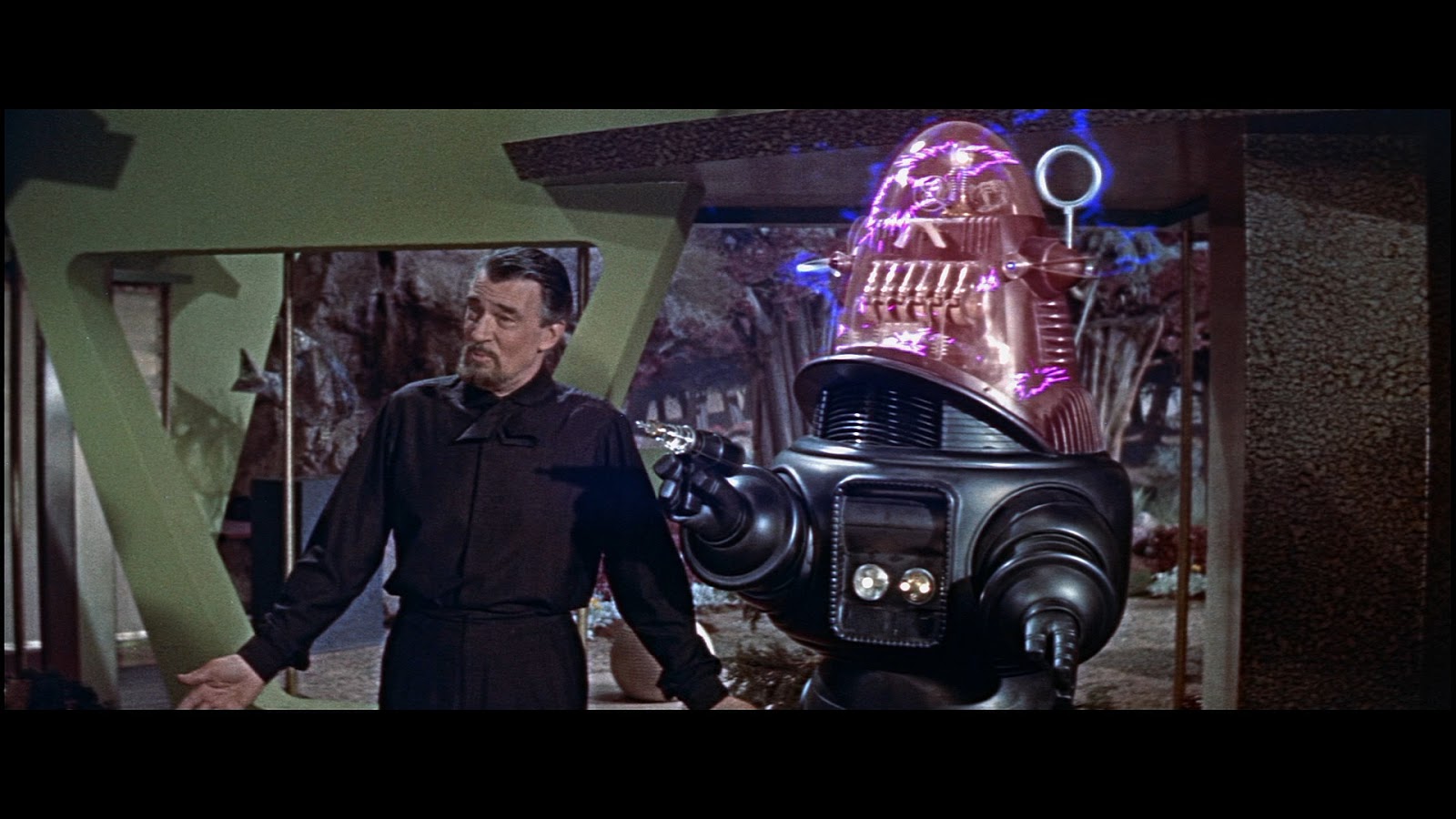

It is ‘The Tempest’ with phasers, lasers, a robot, and an Id. The staging is elaborate and it was budgeted as an A-picture in Cinemascope colour. Mr Miniver is there as Prospero, a man in black, and he makes a good fist of some bad lines. When Robbie and Francis are not filling the eyes, the long vanished Krell dominate proceedings with their Leggo sets. But when Id appears, well, that’s it.

Drebin and company are come to check on an earlier expedition which stopped reporting a year ago. As they approach planet Altair the usual dire warning ‘Do Not Land’ comes on face-time. As usual they ignore it and land. So far, so usual. The inside of the flying saucer is elaborately done compared to the office roller chairs and sun loungers in most Sy Fy of the day.

On Altair they find that only Miniver survived from the earlier expedition. His Miranda, Francis, was born on Altair, and he quickly assures Drebin, known as a stickler for law and order, that he has the marriage licence (and birth certificate?), paying homage to 1950s conventions: Francis was not born out of wedlock. Miniver made Robbie and Robbie made everything else, including the Frank Lloyd Wright desert home in primary colours they inhabit. That is one busy Robbie.

Mr Miniver and Robbie.

Mr Miniver and Robbie.

All the others from Expedition One were killed by some dark, unseen force. Only Miniver was spared, perhaps, thanks to his Dunkirk service. It is hard to believe. The Stranger from Venus would not buy it.

Francis has a tame tiger which later tries to attack her in the company of Drebin who keep showing her his interest. This is a harbinger of what is to come.

By some mystery the ship is damaged. Then two crewmen are murdered! Yikes! The flour is in the gravy now. Lumps and recriminations follow. Drebin shows more interest in Francis.

There is a marvellous scene where an invisible creature attacks the saucermen’s encampment. The pyrotechnics are startling. After the invisible creature, made visible in outline as it tries to cross a force field (the spaceman’s friend, along with Tums), kills two more red shirts, Bart Maverick, for reasons known only to the scriptwriter, rushes forward to meet it mano à mano and becomes, briefly, a roman candle. RIP Bart.

Now Miniver admits Robbie did not do it, that is, build everything in the sprawling ranch style home. The Krell and their wondrous machinery are revealed and displayed. Wow and wow! Many arresting visuals as Miniver does a show-and-tell. Key is the brain booster, which he has used to become an Egghead rivalling Kevin. He impressed Drebin with his knowledge of vexillology. vacuumology, ventriloquism, or something. No one ever explains Robbie’s origins. Is he Krell, or not?

Brain booster. Get it?

Brain booster. Get it?

Every time Drebin shows his interest to Francis, something bad happens. (No, not that.) Stevens as the doctor figures it out. Sigmund Freud has been there and Prospero-Miniver, thanks to the brain booster, unconsciously projects the energy of his thoughts into actions to get the remoter. Evidently, he eliminated all the original party this way, too, probably so that he could watch what he wanted to watch and at full volume. Accidents happened, repeatedly.

Doc tries the brain booster without reading the manual. Bad idea. RIP Doc. Francis and Drebin plan to move to New Jersey. (Bad idea.) Miniver struggles and finally, taking a page from the playbook of James T. Kirk, Drebin talks Miniver to death by citing Ziggy in the original Incomprehensible. ‘Ugh,’ cried the fraternity brothers.

The survivors, accompanied by Miranda and Robbie, take off. Altair goes boom. Must have been New Year’s Eve. No one else will ever again be tempted to rival Kevin as a big brain by using the Krell device.

‘Home, Robbie,’ they cried.

‘Home, Robbie,’ they cried.

The end.

It always ranks near the top of lists of the best Sy Fy, the more so when CGIs cartoons are omitted. More than 30,000 ratings on the IMDb is something for a 1956 movie in this genre. It has a strong but surprising story line, some great visuals, an elaborate background, a slow build-up, and agreeable characters. The comic relief is mercifully brief.

It starts with a twist, putting Drebin in a flying saucer (rather than the aliens) and stays a little off-center of the genre conventions thereafter. Quibbles follow.

If Miniver wanted them to leave, why did he damage the ship, making it necessary for the ship to stay? Maybe he should have visited the big brain booster for a top-up on cause-and-effect.

But then why did id kill all the original survivors of the first mission? Was it really a fight to the death over the television remoter? That seemed likely to the fraternity brothers.

Yet many of the critics linked to the IMDb have some churlish and childish things to say. One derides it because the King Gee uniforms worn by the crew are not shiny. Yep crucial that. Another wants more creature and less feature. Back to the kindergarten with that 7MATE viewer. Another says Shakespeare was not much. [Gasp.] Others tell erring readers which sofa on which they sat to watch it. Crucial that. Others wanted more action and less thinking. Look in a mirror for that.

At the time of its release the pompous ‘New York Times’ reviewer Bosley Crowther waxed enthusiastic about it. Now that is odd. His reviews of Sy Fy were usually condescending, disdainful, and snide, altogether like some professors talking to undergraduates.

Ever after Drebin went to Police Academy to earn a living back in New Jersey, and Miranda set up as a PI in ‘Honey West.’ Miniver went to the Senate to ‘Advise and Consent’ and a reborn Bart went all ‘Maverick.’ None of the B Sy Fy regulars are in the cast.

Nor are any of the crew Sy Fyians. The screen writer, director, and producer were generalists with no Sy Fy visas in the CV. The soundtrack of tones is noteworthy, though where was the theremin?

‘The Invincible’ (1964)

The spaceship Invincible with its formidable array of technologies and a very experienced crew of space explorers arrives at Regis III to find its sister ship Condor which landed there two years before and has since failed to report.

Great precautions are taken. Force fields and robots are deployed. There is a lot of science in the text about these machines and their programs. The crew numbers about eighty. They find Condor and most of its like-numbered crew are dead. Despite full larders on the ship the doctors are sure most of the Condor’s crew starved to death. Very strange. Was it one of those fad diets!

There are no signs of life on the inhospitable planet. If Condor had surveyed it and left, the planet would probably not have been bothered again since there seems to be nothing there of interest or use and there are so many other worlds to visit.

But now there is a mystery to solve. What happened to the Condor’s crew? Exploration occurs. Speculation is riff. The scientists compete in boring each other to death with wild hypotheses.

Then some of their crew go off the air. They are present in the flesh but seem unconscious though wide awake. Think of a Republican congressman and there it is. Mouth open but brain off. This happened to more of them every time that black cloud is around. The black cloud is around more and more.

The black cloud is in fact comprised of a myriad of tiny, fly-sized, microbots evolved from some alien technology of a race long since dead, say two million years ago. The bots surround one’s head and that net burns out the electricity in the brain and makes one into a slavering idiot incapable of anything, eating, drinking, hailing a bus; the victims are only able to vote for Australian idol.

They try to fight the bots with the Invincible’s mighty array of weapons, blowing up a good part of the planet but not landing a punch on these micro-terrorists. Sounds like the foreign policy of some stupor power does it not?

In the end the Captain finally capitulates and decides to blast off, but first the crew has to be accounted for. One principle of space flight, says the Captain, is that no one is left behind alive by mistake or purpose.

Since no Republicans were handy, they hit on putting colanders and tin foil on their heads to hide their brain activity, and set about retrieving their dead and missing. This method works per innumerable Sy Fy movies.

Off they go.

Stanislav Lem wrote reams of Sy Fy, including the novel on which is based the movie ‘Der Schweigende Stern’ (1960) reviewed elsewhere on this blog, though his novel lacks the propaganda inserted into the movie, which insertion led Lem to withdrawing from the production per the official web site of Stanislav Lem.

The initial mystery is intriguing and the description of the apparatus of the Invincible is detailed but mostly superfluous to the plot, story, and characterisations. After such a detailed and long built up the climax seems a squib.

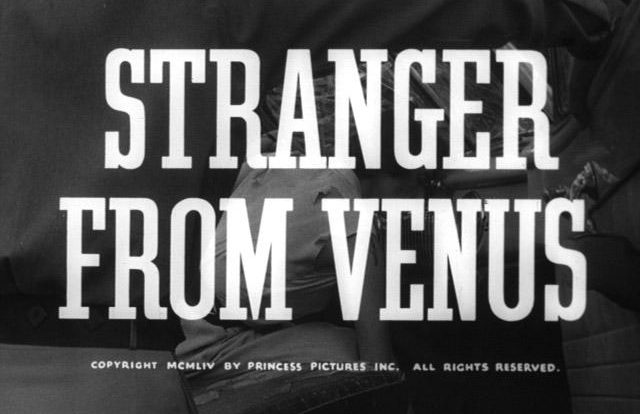

‘Stranger from Venus’ (1954)

Metadata from the IMDb: 1 hour and 15 minutes, 5.4/10 from 294 viewers.

Patricia Neal, driving along a country lane, is blinded by an unexpected light and jerks the steering wheel. The automobile goes off the road and smashes into an inconveniently located oak tree. Wallop! Afterwards a copper examining the wreckage says no one could have survived that crash.

Yet later that afternoon Patricia walks into the pub with a few bumps and bruises. Earlier we saw feet approaching the smashed car with Pat sprawled across the steering wheel. When that copper arrived she is nowhere to be found and neither are those feet. ‘Where is Pat,’ asked the fraternity brothers?

Those are no ordinary feet.

They belong to a man who appears in the village and things gradually happen. He is a stranger, and he later tells the local that he is from Venice.

At the pub we have the local doctor, a stiff-legged publican, a barmaid, Mr Smarm who is Pat’s squeeze, and, shortly, two police officers from the site of the car wreck. Into this gathering walks the Stranger.

He is dead calm, two degrees below laconic. He sits. Yes, he would like a drink. Offered choices he chooses by pointing to a glass. Beer comes. Here is the first clue he is an alien. He says he does not like that (warm beer), Suspicious are aroused.

The doctor tries to chat him up. This stranger has no small talk. That is not all he does not have. ‘What’s your name?’ asks the quack. ‘I have no name.’ Oh, oh.

That is not all he does not have. The quack tries to take his pulse. No pulse.

Mr Smarm tells the cops to arrest the Stranger to find out who he really is and find where he has hidden his pulse. They discover they cannot touch him, try though they might. But he agrees to let them take his fingerprints. He has prints but not human. Well, of course not, he says, ‘I am from Venus.’ Oh, Venus! By now they believe him.

At times he can read minds, but at other times with no explanation he cannot. Blame the script writer or a low battery.

He has no money. Now that is serious in a pub. Who is going to pay for that undrunk beer! The Stranger suggests he work for his keep in the garden. He likes the garden and spends much time among the flowers while the others discuss their reactions to him. This quiet flora-loving stranger appeals to Pat. After Gort he is a change.

Smarm sees his career stock rising if he capitalise on this Venusian, but he does not seem to be jealous of Pat’s affections. Fool that he is! He can use this Stranger to become famous or something. He calls in heavy weights from the capital. The terms ‘London’ or ‘Whitehall’ are not used.

The Stranger says he wants to meet world leaders to explain his purpose once he recovers from flying saucer lag. Nuclear testing will alter the Earth’s orbit and such a change would have an impact on Venus as well as Venice. In return for putting aside nuclear weapons, Venus will help Earth develop other technologies (like solar and wind). A major delegation awaits in the mother ship once the Stranger has arranged a meeting.

The Heavy Weights say no world meeting can be arranged so quickly in the circumstances. Secretly they plot to lure the mothership into a trap so they can seize its technology. (Aside, technology transfer does not work that way. Give a caveman an iPhone and he will use it to spilt rocks. I have tried this with the fraternity brothers and confirmed this result.)

Wait! The Stranger has an iPhone that lights up when he communicates with the mother ship. When he loses it, he becomes animated for the first time.

It is slow without special effects. The Stranger does not have a shiny suit or any of the other paraphernalia of Sy Fy aliens. There are a lot of extras as soldiers surrounding the area and fencing it off. Many rustics are shown listening to radio reports. Much equipment is seen to be deployed and it does not look like stock footage. It hardly seems a cheap production as many critics claim. It does seem a story that does not need a lot of artifice.

The process by which the Stranger reveals his origins and convinces the others is compelling. The reactions of the members of the group in the pub are interesting, too. The scientists, the doctor and later a figure from the Ministry, believe the data about fingerprints and pulse. After a nocturnal visit from the Stranger, the publican regains full use of his stiff leg. He then is convinced. Others are slower to admit it.

The barmaid prays for guidance and then accepts him at face value as a gentle soul from God’s creation. No doubt acceptance would see it banned in Alabama where only the sins of football players and Twits are forgiven.

The setting is deliberately ambiguous and this subtlety has been lost on most critics. The radio announcer has a mid-Atlantic accent, Neal carries coal-country Kentucky in speech, the publican is very British, others are muted. Moreover, when the coppers come from the road accident they wear gaudy uniforms and carrying sidearms. These are not 1954 Bobbies. When the Heavy Weights arrive the offical car sports at tricolour flag, not the Onion Jack.

While a journalist is present, he waits for government permission from the Ministry of the Interior to publish. The village looks British to be sure, but there has never been a Ministry of Interior in the United Kingdom. What self-disrespecting Brit journalist ever waited for permission to publish? D-Notice be damned!

The setting is contemporary to 1954 but it is not quite England and certainly not the USA. Orthogonal rotation gives us a variant reality making the setting more general. This is not England, this is anywhere. Most of the critics seem to think these aspects are a result of the small budget, whereas I think they were contrived to add to the uncertainty, the mystery, and the strangeness. It works.

Some of the cockamamie interpretations by critics may stem from the origins of the film. Yes it is resonant of ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951) though it stands on its own.

Yes, Patricia Neal plays a similar role in this outing as she did in ‘The Day Earth Stood Still’ though she has much less to do here. Whew! No Gort. She had moved to England with Roald Dahl and the gossip is that they bought a house and to pay for re-decorating and furnishing it, she went back to work. But of course the film world in Great Britain had a pecking order and she was not in it.

His Lordship Desmond Leslie, a specimen who defines the English eccentric, was a UFO devotee, and he set up a shelf company to produce this film Neal wanted work and he had just the thing for her.

Helmut Dantine plays the Stranger with an Austrian accent (though in one scene he switches through French, German, Spanish, and Russian to prove what an alien he is).

He had been imprisoned by the Gestapo for anti-Nazi activities after the Anschluss and it took a really big bribe to spring him; then he fled to England. He made a film career there in 1940s playing Naziis. Never a lead but always there in a dozen films in 1942 alone where on celluloid the Brits were clobbering the Nasties. Post war he moved to California in the hope of more and varied work in the bigger pool there but he never quite made it as an actor, and realising that he went into directing and later producing.

The film did not get a theatrical release in the United States, perhaps because Twentieth Century-Fox protected its investment in ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ or because there was no theremin music. It has been presented under other titles, e.g., ‘Immediate Disaster’ and ‘The Venusian’ on late night television.

Not easy to find and perhaps that explains the few IMDb comments and votes. I watched the version at the Internet Archive which seemed to be complete. There are edited versions about the gossip says.

‘Planeta Bur’ (1962)

This Soviet classic (‘Planet of Storms’) has been an undercover agent of influence in plain sight for years in the West as ‘Voyage to the Pre-Historic Planet’ (1965) and ‘Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet of Women’ (1968). The fraternity brothers have wall posters for the latter film. These latter two films were cut and pasted for English-speaking audiences. Sherlock Holmes put in an appearance in the former and Mamie van Doren in the latter. Wall poster, indeed.

Having feasted on these two simulacra, it was time for the subtitled original.

In 1962 the Soviet Union was winning the space race and to promote that achievement rubles flowed into science fiction movies like this one. When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon, the ruble spigot was turned off.

Here is the set up. Three space ships are approaching Venus. While they are all crewed by Russians, there is someone who say ‘OK’ a lot and his name is Allan Kern. There is no military symbolism or insignia to be seen.

Maybe the effort is a combined international effort. The film opens abruptly and no explanation is given, though there are many references to the Earth rather than Russia.

Each ship has a crew of three. Wallop! Two ships remains. What else? A meteor clobbers one ship. The carefully contrived plan of landing is obliterated with it. Earth instructs the two remaining ships to wait two months while another space ship is launched and joins them.

Two months eating airline food and using that plumbing. No thanks! They come up with a new plan and Earth control rolls with it. (Sherlock did this part in one of the Cormanites.)

The he-men decide to leave one ship in orbit and to land with the other in two stages. First a surface lander will drop down to scout a spot with good duty free shopping, and then the second ship will land there. ‘OK,’ say Allan Kern.

The third member of one crew is a woman and she is left in orbit to communicate with Earth. Unlike the Yankee Sy Fy of the time there are no sexist remarks about a woman doing a man’s job, though she is the squeeze of the captain of her threesome, their relationship is chaste. So far so good. She is left in orbit not because she is a frail and flighty woman, but because she knows to turn on the radio as communications officer. Push the big red button. Ah huh. Nice try. That did not fool the fraternity brothers for one minute. She is left behind because she is frail and flighty woman.

While the men are resolute, she dithers later and in one light moment she floats around the cabin. None those resolute newish Soviet men would do that. Even so this subtlety is way beyond Hollywood at the time.

On Venus they find a lot of Godzilla’s cousins and fend them off, sometimes with revolvers. It is an inhospitable place, boiling mud, flowing lava, clinging plants, rubber dinosaurs, a lot like Wyoming. Kern has a big robot called ‘John’ who is snooty. Unless addressed politely by name, he ignores instructions. Think Siri, who does not react well to some of the things the fraternity brothers say to her. Robo John also serves as a mobile computer. Try putting him in a pocket. Robo John is useful but in the end it fails the Laws of Robotics. Bad robot!

Unlike so many British and Americans on other planets, these Soviets do show scientific interest in it, collect samples, discuss findings — when not hacking and shooting the fauna — and speculate about intelligent life. So many of the Anglo-Brit planeteers are bored, indifferent, napping, smoking, and lining up for the return trip without a backward glance.

The Soviet equipment was not made by the lower bidder, because it works, and they return to space, and presumably to Earth. But we get no triumphal return (unless I hit the off button, too soon).

They have a hovercraft that is also a submersible, though it is not quite up to James Bond-standard.

Even so the under water sequences are well done, As is the episode of weightlessness mentioned above. These effects would have been quite fascinating at the time. They still are considering there is not a CGI in sight.

As they leave the planet the ending is spooky, but it is not connected to the preceding story, and seems an afterthought, as though inviting Roget Corman to do what he did with it, and get two more movies out of it.

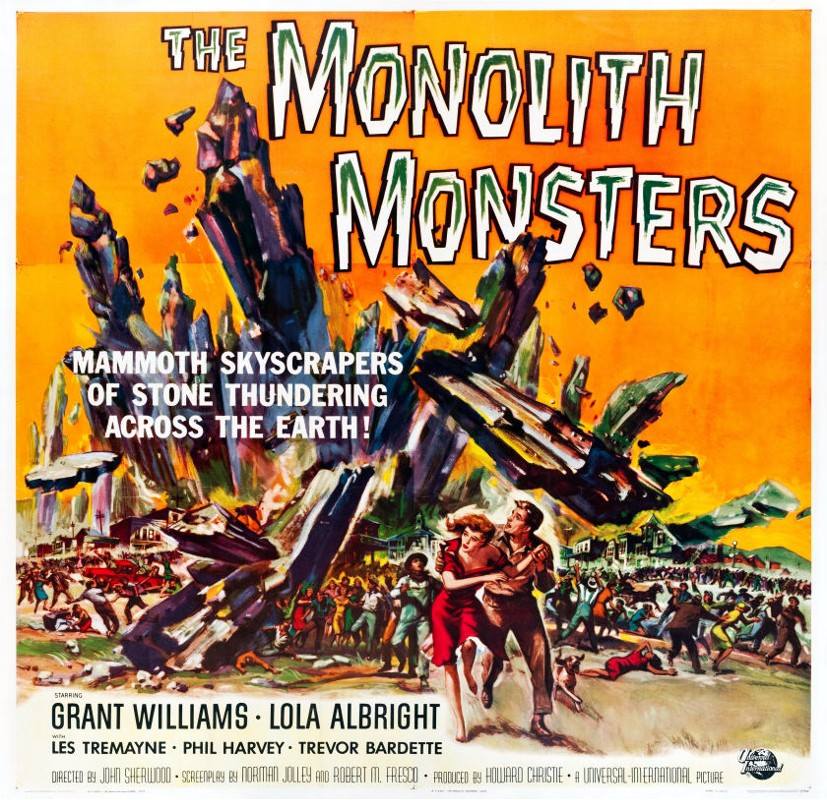

‘The Monolith Monsters’ (1957)

Meta data from IMDB: 1 hour and 17 minutes 6.7/10 from 2263

Hard Rock come to San Angelo in a big way. The bigger they are, the harder they fall; the more they fall, the more of them there are. Figure that out.

Monoliths, yes; monsters, no. This is a creature feature without a creature. Just the sort of thing that confuses the fraternity brothers.

These monoliths missed Stonehenge and Carnac and hit the desert Southwest as so much Sy Fy did in the 1950s. A r-e-a-l-l-y big meteor hits the desert. Boom!!!!!

No one notices. Richard and Babs from ‘It Came from Outer Space’ (1953), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, usually spot meteors but they must have at their anatomy lessons.

A park ranger finds a rock chip on the road. It looks different. Odd. He takes it back to the office. Too bad.

This first act is very classy. the ranger stops the car to take a look. He uses a rock to chock the wheel of his vehicle on the slope without a thought. Then when it is time to go, he kicks it away and notices its peculiarity. He tosses into the car for subsequent examination.

Back in town he takes his kit and the rock into the office, which has been closed all day in the hot sun and he opens up the door transom and the back window for the air. This is all so brisk and natural that it hardly seems a prelude. But every one of his actions has unforeseen consequences.

Spoilers below.

Later he kips on a cot in a side room and, as it does in the desert, it rains hard and water blows in from the back window onto Rocky lying on the work bench.

Next morning his offsider, the affable Grant, comes back from a road trip and finds the back room a shambles and his buddy….. standing in for Lot’s wife — petrified.

Bad. Inexplicable. Much Geordie speak about rocks, which did not remind me at all of the Geology lab I did as an undergraduate. Nothing would. Gone.

Conclusion? Rocky did it! Others fall victim to Rocky and his friends. Worse.

Edie’s prize pupil goes all ‘Them!’ and is rushed to LA and an iron lung kept on standby for Sy Fy movie use. More Geordie speak about carbon, silica, and pancetta. Who knows?

Rain on the rocks makes them grow into monoliths. Nice skyline shots of monoliths against the desert sky painted on a travelling matte. Tourist attraction in the making, but then….crash they fall over and fragment. Each fragment grows into a monolith in the rain and then falls over. Thus do they at once proliferate and move. They are mindless and destructive. Reminds me of some people I know.

A call to Mr Pomfritt, doing a summer job at the weather bureau, says more rain is coming. Yikes!

Here they come!

Here they come!

No effort is made to negotiate on either side. Grant with the help of a visiting professor (for once good for something) and the local newspaper proprietor figure it out. As much as Rocky likes water, Rocky does not like salt water. Okey-dokey! Now what? The Gulf of Mexico is too far away. The Pacific Ocean is in use. But, but, but the Morris Dam is just around the corner. Sprinkle all the salt shakers in town into the reservoir and then blow it up!

Everyone agrees this is a good idea. The fraternity brothers always like a big bang.

By this time higher authorities have been alerted and are arguing about whose KPIs cover the situation. Consultants are showing each other Power Point presentations about paper, scissors, and rock. Lawyers are amassing billed hours without uttering a word. Pollsters are drawing samples to interrogate. The Twit in Chief is playing golf. This is crisis management at its best.

The rocks keep coming, falling on people, animals, farms, but missing Republicans.

Without waiting for approval, Grant blows up the dam. Much congratulating follows. Edie falls into his arms. ‘Aw. shucks.’ mutters Grant. The End. Off camera the police arrest Grant for blowing up public property and turn him over to Homeland Security and their r-e-a-l-l-y big waterboard.

It is crisp and direct. The staging of the rocks is striking on a wide screen. The actors are solid, including some ever reliables, like Lee Tremayne and Trevor Bardette. Phil Harvey as the first victim is utterly convincing as an ordinary Joe doing his job. Edie Hart is luminous long before Peter Gunn came along.

Director Jack Arnold is credited as a writer here and his sure hand shows. Those who do not know Jack, should. Paul Frees supplies the narration and Troy Donahue makes a brief appearance.

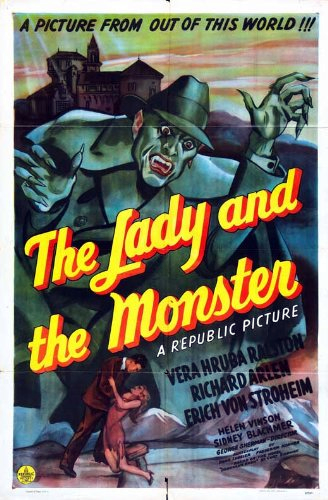

‘The Lady and the Monster’ (1944)

IMDB metadata: 1 hour 26 ,minutes 5.6/10 from 199.

Despite the lobby card and the newspaper advertisements, much to the disappointment of the fraternity brothers, there was no monster. There is a lady, and about her more at the end.

The ubiquitous Curt Siodmak published ‘Donovan’s Brain’ in 1942 and it spawned this movie, and two others. Siodmak went to this well again in ‘Hauser’s Memory’ (1968) which in turn generated two derivative films.

In distant Arizona a castle in the desert is inhabited by the requisite mad scientist, in this case, the singular Erich von Stroheim. Igor assists. Upstairs is a live-in niece who is the lady of the title, and a grim and taciturn house keeper. The cast of Otranto is complete.

A small aircraft crashes nearby and the local plod sends for the mad scientist since he is the nearest doctor. The pilot died on impact but his passenger is barely alive. This is Donovan, a shady millionaire.

Ah ha!

Erich has been trying to keep alive brains from monkeys, rabbits, rats, and Republicans in jars. The laboratory is full of backlit jars of milk with objects within. Igor and the niece pitch in as required. The housekeeper looks on in disapproval.

Donovan dies and Erich gets his Egyptian nose pickers out and extracts his brain. ‘Hand me another Mason jar,’ he cries! Niece hesitates but Igor obliges.

The brain lives! (Donovan was not a Republican if he had a living brain.)

Next Erich dials up the brain for a chat. Much EKG tape comes from the adding machine. Strange sounds are heard. The lights dim. Igor sits up with the jar as if with a sick child.

He and Donovan’s brain commune. Igor is putty to Donovan’s indomitable will. He manipulates Igor who assumes his personality, strong, bitter, commanding, mean. Yes, this manager is managing. Shenanigans follow.

Donovan’s widow sheds not a tear but seeks the ill gotten gains. Her oily shyster lawyer ably assists. In the middle it becomes a film noir as Donovan reborn in Igor sets about his plan, the niece tries to break Igor away from Donovan, while Erich encourages the brain-bond, and the housekeeper dusts.

There is a conclusion in laboratory. Where else? Much sugar glass is broken. The housekeeper gives notice with a revolver. The niece tips over the Mason jar, and dinner is on the way.

This product from Republic Pictures is a classy B movie with superb lighting and deft camera work. When Donovan possesses Igor he is lit from below. The lab seems sometime large and other times small to fit the mood, thanks to the lighting and camera work. The pace is snappy with the exposition kept to a minimum. Most of all there is Erich von Stroheim, mad and bad and unique.

A number of early John Wayne vehicles bore the Republic badge. If not an A studio it was B+ in the Hollywood pecking order of the day, until about April 1944 when ‘The Lady and the Monster’ was released. There is quite a backstory.

The President of Republic pictures had seen the niece skate in Europe and brought her to Amerika where he would make her into a movie star. She changed her name from Hruba which no one could pronounce, except Roman Hruska, to Ralston. She had no acting interest, training, experience, or ability. It shows here in this her first wooden role. She spoke little English and recited most of her lines phonetically. Because it was a vehicle for her, the President threw much more money into this picture than the usual B feature. A lot more. He did the same in the next four or five films she made until Republic Pictures was near bankruptcy and a management coup turned him out. The notoriety she gained from this scandal briefly extended her career but it soon ended.

Erich von Stroheim’s career was a roller coaster. In 1936 he stole the show in ‘La Grand Illusion’ and in 1950 he almost did it again in ‘Sunset Boulevard.’ In between he played mad scientists, shoving George Zucco aside. No easy feat that. He started years earlier as a director and acted, at first, only to generate income for his projects, and to put schnapps on the table.

Richard Arlen who usually played light weights turns in a superb performance in the transformation from skirt chasing Igor to deadly Donovan.

‘Downsizing’ (2017)

Metadata from IMDB: run time of 2 hours and 15 minutes at 6.0/10 from 4411 ticket holders.

A couple decide the solution to (some of) their problems is to downsize themselves. Years before a Norwegian scientist found a way to shrink the kids and anyone else. (Remember that episode of ‘The Avengers’?) After much angst they do so, well, sorta, because at the last moment after hubby has done it, wifey baulks and backs out. Mini-him is now on his own. Adventures in Disneyland follow.

SPOILER ALERT.

I loved the characters, the boring physiotherapist Matt Damon, the devil may care Serbian neighbour, the laconic boat captain, and most of all the feisty Vietnamese. Watching them bounce off each other in their little world is diverting for a time, but not two hours and fifteen minutes of it.

The story is like a combined Thanksgiving and Christmas lunch with the extended family. There are too many courses. It just goes on and on and loses its way. No sooner is one course served than another appears competing for table space. Desserts are followed by savoury courses, again.

What is it about? A satire on materialism? That is why Matt and Audrey decide to shrink, so their dollars will go further and they can have a big house like those In Elkhorn. Is it a warning of things to come about climate change? Hence the Norwegians digging in. Is it about being different? The discrimination against the little people. Is it about dislocation? The Vietnamese refugee. Is it about saving the world one hot meal at a time? The food distribution. Is it about saving the world? The original Norwegian concept. Was shrinking a metaphor for retirement, since no minis seem to work, though in fact some do, and in social isolation. Is it a parable according to which paradise has a slum to service it, pace ‘The Magic Mountain’ (1924) by Thomas Mann?

The list goes on. Way too much to digest in a sitting. Indigestion follows.

There are so many themes that they get lost, one after another, and none is developed. The mini-me-s live in Disneyland, and some one makes little cars and buses for them, but who and why since in the end they represent less than three percent of the population.

The Serbian and the sea captain are vital to the Norwegian’s final plan. But why? No idea. They take Matt along. Why?

Why are there Norwegians in the first place” (The external shot of the Norwegian laboratory in the opening looked a lot like the College of Business office building at UNO in Benson.) To have fjords latter, I guess, there had to be Norwegians. But why were fjords even in it? It started in Omaha and went to sunshine in Arizona and then fog in Norway.

Can mini-theys only live in sunshine? Aren’t there any mini snow shovels?

As the doomsayers disappear underground, the best lines in the film come from the Serbian ‘They’re just people. They will behave like people. Fight, kill each other. The usual.’ There is no technological salvation from humanity itself. The final fizzle was a sign not to take it all too seriously; that is understood, but the joke then is on the audience that has sat though one hundred and sixty-five minutes to get there, not counting the deafening advertising barrage before the feature, which always set my teeth on edge.

‘Downsizing’ should be downsized by at least forty-five minutes. The prologue about the discovery of shrinking could have been done in a two minutes voiceover, and without that prologue, the epilogue could be omitted, too.

Boring Matt made one big decision because he thought he knew what he was doing. The consequences followed. Nothing is added to his character by giving him a second big decision, the more so when the has no one to go with him. His only three friends never for a moment consider the hole in the ground.

And none of the problems of these leprechauns has been addressed. If they are but three percent, will airlines cater for them. Is there an ACLU division for minis? Will there be any new minis now that the Norwegians have given up?

Leafing through the paper, the indication of the Sy Fy genre caught my eye and since there seemed to be no CGI exploding heads involved, I read on and came across a name I knew, Alexandros Papadopoulos, to the fraternity brothers that is Alexander Payne. His ‘Nebraska’ (2011) was compelling. ‘About Schmidt’ (2002) was memorable. ‘Election’ (1999) conjured dark memories from high school. He knows a story and how to convey it. Better luck next time. We missed his ‘Descendants’ (2011) despite the Hawaiian setting.