For years I have heard pygmies declare that ‘ein(e) Berliner’ is a pastry. This is said for the purpose of belittling Jack Kennedy’s use of the phrase, in a speech in Berlin in June 1963, and to deprecate him, too. A search on the web will produce many hits for examples. Enough to satisfy those easily satisfied.

Below is the index card he wrote to insert the phrase in the speech. Before pedants begin correction the spelling, note that it is phonetic and was jotted off in the car on the way to the podium.

Once or twice I have bridled at this casual derogation, based on my own study of German, but that was always dismissed by the interlocutors.

Then one thing was obvious ,,, to those who looked. The Berlin audience in 1963 understood the phrase in the way Kennedy intended.

A crowd of 450,000 according to Wikipedia.

A crowd of 450,000 according to Wikipedia.

No PhD ever had such a reaction from such a mass of listeners. At the time, at the place it was a message received five by five, loud and clear. There is plenty of evidence on You Tube.

The other thing is that it is a grammatically correct statement as even a beginning students of the language know. I have had that confirmed many times over the years by German speakers, and again recently in the image below, taken from a Deutsche Welle website after a murderous attack in Berlin in 2016.

Perhaps the pygmies will now mock these two woman, too, while they bury their dead.

The attacks of pygmies on giants are endless, often petty, always trivial, and seldom accurate. The attacks satisfy some need in the pygmies.

No doubt some entrepreneur in Berlin has been marketing donuts with this meme for years. No doubt someone will offer alternative-facts. It was ever thus.

The other sign says ‘Berlin will hold together.’ Perhaps the best rendering is ‘Berlin will remain.’

Sydney Festival 2017

It’s a wrap for another year for us Festies. We went to five shows and found three winners, one curiosity, and the fifth.

In first place is Retro Futurismus. Whatever those Davy girls are on, there should be more of it! Followed closely by Ladies in Black. And showing, Measure for Measure.

That a mature Shakespeare plays came third is a surprise to us, too. But it was in Russian.

Ladies in Black was good as Goody’s should be. [The cognoscenti will get it, and hoi polloi won’t, and that is as it should be.]

Retro Futurismus is genre-free and sometimes gender bending it is. Vaudeville one reviewer called it, and that will do. It is a variety show with some singing, some dancing, some wall climbing, some aerial without a net, a singing slinky, some ultraviolet light, and some more.

We found it amazing what can be done with bubble wrap, kitchen tongs, and house bricks. Strewth!

I am at a loss for words, except to say the next time Retro Futurismus puts on a show, I want to be there. The wit, the creativity, the energy, the bonhomie were all contagious.

Though I was intrigued by the description, i failed to list it when we consulted about our Festie this year. Why? Because it started at 09.45 pm, which is a good hour after I am in my pyjamas with a book in hand. But Kate said it was go, and so we went. She was right again. It was go!

We took an Opal bus each way and waited four minutes and nine minutes. The ride was twenty minutes. This I mention to indicate how easy and convenient it was.

Channel 7Mate and life.

During the United States football season I watch NFL games recorded on 7Mate. What an eye opener it is. No, I do not refer to the games, but to the advertisements, through which I fast forward at light speed. I try to do that but sometimes fail and when I do, I always regret it. Crass, vulgar, and stupid do not begin to describe the adverts, the products, and programs they promote.

The advertisements are for a demographic I know not, and I want to keep it that way.

The products usually promise the earth for $9.99, Hair growth for baldness, travel around the world for nothing, free tickets to this and that, invariably spectacles, like giant trucks crashing into each other, I never heard of and am glad of it. Many of the commercials imply there is a secret to getting these things, which will be revealed for a few dollars. Thus there are secret tricks to get first class travel for a pittance. Many concern weight loss, usually by eating. The suppressed premiss that there is a conspiracy known to others is a motif in many advertisements.

To say that the appeal of these commercials is simple and simple-minded is the kindest thing I can say. The smart people who identify and target the demographic of watchers (gulp, and that includes me) decide to do it that way.

More revolting still are the other 7Mate programs relentlessly advertised in breaks during the games usually described as bigger, louder, longer, ruder, and ever more …[tiresome]. Invariably they involve men doing stupid things while chortling about it.

Here is a sample:

Among the more respectable examples include farting contests, with ignition, projectile vomiting with a feminine twist. (Don’t ask!) Others involve crashing into immovable objects either headfirst or in vehicles of some sort. Then there were the urine drinking contests. Many of the adolescents filmed in these trailers are old enough to know better. Animal house with scraggy grey beards and one hundred word vocabularies.

At times the programs that feature these deeds, also have audiences cheering them on. Believe it or not.

Many other programs involve automobiles being lovingly stroked. or guns likewise stroked. What is it about stroking metal? Well whatever it is, I don’t get it.

Other advertisements for programs involve sweaty men playing with heavy machinery. They are not working for a business but rather wildcatting on their own. Ostensibly they might be digging for gold: X marks the spot. But really they are just having a high-ho time with a gigantic earth mover.

There are also movie trailers and they come from the same stable. Blokes killing CGIs. Computer Generated Images that is.

In every case the text is aggressive, belligerent, loud, and limited. Everything is a fight, a war, a battle, a contest. All those couch potatoes love watching others go at it. Even an auction is covered as if it were a fire-fight, as only those who have never been in a fire-fight could do. The men in the trailers, and yes they are invariably men, are usually unshaven, unwashed, or wearing greasy clothes, or the trifecta.

A few years ago Channel 11 of the Ten stable, showed the games and it was the same there. There is nothing exceptional about 7Mate except that I happen to see it.

Yes, I watch NFL games. It is the only United States sport free to air here, so it is the one I watch. I would prefer the NBA. I have given up on MLB because the players seem to lack fundamentals skills; the games are over-managed; and the commentary is so diffuse, oh for Vin Scully who was always interested in the game before his eyes, unlike those I last heard who were bored silly by the game and preferred to reminisce about dinners past. Maybe they are personalities who are feeding the twits who follow their tweets.

Jan Morris (1926+) née John Morris, ‘Venice’ (1960), Third Edition (1996).

A charming, enthusiastic, and altogether delicious memoir of life in Venice in the 1950s. It has an intimacy born of residence which goes into the details of everyday life, like rubbish removal, and the weekly shopping by dingy. Indeed, it includes many asides on the perils and joys of keeping a small boat for just such mundane purposes, and the surprising array of regulations and taxes that a humble, leaking rowboat attracts, watertight or not.

The Venice of the 1950s is gone, but Morris is confident that as long as there are Venetians there will be a Venice. The gene pool is strong, deep, resourceful, and clever enough to withstand the tides and times, Morris opines in the 1996 introduction to the reprint of the book, originally published in 1960.

The approach is almost ethnographic, as an anthropologist living amongst a tribe in the African savannah, he observes, notes, compares, enumerates, and ponders the meaning of what he sees, but with much more affable affinity than a Cambridge don in khaki kit roughing it for a few months in the jungle on the way to promotion. Morris spoke enough Italian to get to know the regulars he met, and enough to talk his way into some places not usually open to nosey beaks. He combines with those assets a keen eye and a tireless pursuit of detail that would satisfy John Ruskin. To these he adds a bonhomie that is hard to resist. Well, why resist it at all?

A quiet day at San Marco.

A quiet day at San Marco.

Day by day over the months Morris weaves together many asides on the history that brought Venice to the current point; these accounts often take the form of lists. That might sound boring, but it is not. Consider the following example as one of many instances.

Here is Morris’s dictation while standing on the tiny balcony of the flat there was:

‘To the left is the palace where Richard Wagner wrote the second act of ‘Tristan,’ and just beyond is the terrace from which Napoleon Bonaparte once watched a regatta. Near it is the house where Robert Browning died, that Pope Clement lived in it, the Emperor Francis II also stayed in it, and Max Beerbohm wrote about it. Across the way at that point is the home of the Doge Cristolo Moro, sometimes claimed to be the original of Othello, and to the right is a palace once owned by a family so rich that it is still called the Palace of the Money Chests. At the corner is the little red house of the poet D’Annunzio wrote ‘Notturno’ there. At the Convent next door Pope Alexander lived in exile from Rome. King Don Carlos of Spain once owned the next house along. La Donna of ‘La Donna è Mobile’ lived nearby. Away to the right, is a palace where one of Byron’s paramours suicided.’

All of this lies within one learned glance.

That is both a comment on how compact is the core of Venice, and also, and more importantly, a comment on what a magnet it has been for the great and good and the not so great and the not so good over the centuries. Yes, Adolf Hitler met Benito Mussolini there in 1934.

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

Followed shortly by Indiana Jones.

Morris goes on to enumerate and describe the many watercraft to be seen in the lagoon from towering cruise ships to garbage scows, to vaporetti and gondoli, and in many cases goes into the etymology of the terms in part to show the polyglot past of Venice with its Arabic, Islamic, Roman, Teutonic, and Byzantine influences, turning the catalogue into a history lesson, spiced by Morris’s own experiences in dealing with many of the craft as either a passing boatman, or as a passenger.

Venice conjures the gondola and Morris gives it due respect. Totemic though it is of Venice, there is no clear explanation of its origins, purpose, or use. Why does it have three notches in the bow? Why is it propelled by a pole and not an oar? Why is it painted black? While the number in the water has decreased by many factors, it remains in demand … by tourists. Morris offers a charming account of both past uses of the gondola and the occasions when contemporary Venetians make use of this clichéd but inevitable device.

Like others who have written of Venice, Morris sees in it a deeply ingrained commercial imperative to make a living out of trade. Having no natural resources, Venetian has always been a broker bringing products to a buyer at a premium. The commodities that Venice can make a profit trading have diminished and disappeared, that is, all but one. The one commodity that Venice retains a monopoly on is itself, and so it trades on itself and does that to a T for Tourism.

Jan Morris.

Jan Morris.

Upon completing the book, I am not sure what to make of it. To read it is to envy the author’s mastery of the exposition. This writer could make a recitation of a telephone book interesting, and indeed, did so in these pages. In some ways it is a memoir of a world now gone. As Morris found even while living in Venice human intervention changed the face of Venice time after time with causeways, channel dredging, factory building, and more, and also the lagoon itself makes changes, eroding what were once residential islands into little more than hillocks of sand.

But the more Venice changes the more it remains exactly the same! Grasping and enchanting, mercenary and magnanimous, seedy and edifying, grotesque and elegant, universal and unique, quite unlike any place else.

‘Measure for Measure’ (1604) by William Shakespeare.

We saw the Pushkin Theatre’s presentation of ‘Measure for Measure’ in Russian at the Sydney Festival. As homework, this inveterate student read the Folger Institute’s online version the morning before attending the evening performance. It helped a lot, having the major events and speeches in mind. The play had surtitles, which were easy to read, accurate to the play (as I recalled it from that morning’s reading), and also quick to keep pace with the action. Because I knew the play, I did not need to read every word of the surtitles, ignoring the players, to follow the action.

Originally classed as a comedy, ‘Measure for Measure’ is now canonised as a problem play. It is certainly serious as it touches on torture, rape, tyranny, hypocrisy, capital punishment, execution, and other problems that remain with us.

The Duke is tired of the responsibilities of office and curious to see what happens without him; off he goes on vacation, leaving Angelo in charge. Angelo is far more strict that the Duke, and becomes a scourge for Vienna. However, he is tempted to carnal knowledge by the beautiful and chaste Isabella. He will free her brother from prison and a death sentence if she will bed him. Her brother is guilty, by the way, of very same carnal knowledge of Juliet. The comic relief is provided by Lucio, a hanger on. There follow tricks and ruses in which everyone gets what they want, except Angelo, though he comes out of it pretty well. Most summaries refer to him as corrupt, and maybe he became corrupted, but he has a crisis of conscience at the beginning. He is no cardboard figure.

One might say the greater villain, if villain there must be, is the Duke himself who contrived the whole thing as an entertainment for his jaded eye. He manipulated the whole situation, and plays on the characters in Acts IV and V like puppets. At the end Lucio is sent to be hanged for slandering the Duke, whereas in this performance, which has edited the play down to 110 minutes, he is sent to be whipped.

The play is indeed the thing. The production was marvellous. Full of energy and light. It ran straight through with no interval which sustained the momentum and energy. An excellent approach. Changes of scene were marked by a swirl of the characters around the stage leaving upstage those in the next scene while the others retired to the position of a chorus looking on and occasionally reacting. The actors were on stage for the duration. Costume changes were effected behind the stage props, four red block that turned out to be….

We particularly like the first dance sequence between a blindfolded Angelo and Maria as Isabella. The bass playing makes sense after a few minutes.

There is a trailer on You Tube at

There are also some interviews with the producers and actors discussing the themes in the play.

It surely took some courage to include a Russian language production in a large theatre in the Sydney Festival. There must have been wise heads demurring all along the way. Too risky. Too outré. Too complicated. Too hard. Too…… too. No doubt I would have been one of them. Wrong. Chapeaux!

How easy it all was. I could command to the iPad screen the authoritative text of the play when I chose to do so. No trip to the library or bookstore to find all the copies gone. I printed the tickets at home so no queuing up. The surtitles worked perfectly to bridge the language barrier.

Moreover, we drove into the Rocks, parked at the front door of the theatre, ate a good dinner a few doors down the street, and walked back to the theatre for the show. To go home, it took fifteen minutes from leaving the theatre to entering the house. For that evening Sydney was like small town. The more so since we saw some people we know in the crowd.

‘Venice: Pure City’ (2009) by Peter Ackroyd

The book is an elegant and languid meditation on the city of Venice, the one in Italy not the one in California. It tells the story of Venice through thematic chapters rather than a sequential history. The chapters run ten to twelve pages, easily digestible in a sitting, and the segues from one to another and within each are smooth as the surface of a pond on a still day. Without a doubt the man can write. The book is replete with watery images, metaphors, comparisons, similes, and tropes. I felt moist reading it at times.

A sample of the chapters includes; Origins, Trade, Refuge, Stones, Chronicles, Secrets,…..

Leaving aside a myriad of details, the heart of Venice was and is trade. It made itself an entrepôt for more than a thousand years. Having no wealthy terra firma, having no mineral riches, having no vast population, it lived by wit, barter and trade. It became the European end of the Silk Road. The merchants Shylock funded sailed into the Black Sea and along the Levant coast to bring back to Venice the luxuries of the East and sold them in trade fairs in Venice. The first Venetian carnivals were commercial expositions.

During its long ascendancy, when violent change was the norm in other polities, precipitated from within by ambitions or ideologies or from without by invasion, Venice remained stable. The city lived with the constant threat alta aqua, which made Venetians pull together, however much they grumbled, like no others at the time. Until Napoleon in 1804 joined it to the Italian kingdom he created for his brother it had stood apart from one and from all. Having no choice Venice reluctantly and slowly became a part of Italy. Earlier when Niccolò Machiavelli rhapsodised of a future Donna Italia he did not include Venice in it, and in this he was not alone seeing it as an enemy of Italy, not a part of it.

In Venice the commercial imperative reduced everything to a contract, and copious records were kept which miraculously survived despite many catastrophes natural and human that often destroy the past. Ackroyd has immersed himself in the dry and dusty ledgers when not walking the campi and picked out some very apposite instances for the reader.

Venetians were traders for whom the sea was the highway. They bought cheap and sold dear and on the margin prospered. Though the merchants were private businesses, their activities were supported, encouraged, promoted, and taxed by the commune as a whole. To specify, the ships were built and owned by the commune and rented to merchants complete with crews. There is a parallel here to George Pullman and his famous railway cars, which are treated in another review on this blog.

Because of the historical and ever-present threat of the water the communal spirt ran deep, and lasted longer even in the age of Enlightenment individualism. In Venice the whole comes before the one. Else everyone drowns. The comparisons to Amsterdam are many.

Like many others he is impressed by the Venetian drive for order and regulation, the more so in the face of repeated Venetian corruption, extortion, embezzlement, and fraud. Shylock was the least of the problem for most merchants of Venice. Ackroyd is absolutely deadpan in the chapter called ‘Merchants of Venice’ in which he does not mention William Shakespeare and his Venetian play. If he did, I blinked. Earlier he does mention Venice’s most famous literary tourist, Gustav von Aschenbach from Thomas Mann’s mediation on life and death … in Venice.

Everything was put down on paper, moreover, everything was kept totally secret. There is the paradox, everything was recorded, included the energetic informing on each other that kept the authorities busy processing, but nothing was said. Ackroyd cites some remarkable examples of the ability of Venetians to keep secrets. They make all those Stasi agents in the Deutsche Demokratische Republic (DDR) look like blabbermouths. There are many, and to this reader, surprising comparisons to be made between the DDR and Venice in matters of secrecy, security, and surveillance and the high cost of such social control.

In the case of Venice the campi — the residential squares — made surveillance unavoidable even for those few who were not interested in spying on their neighbours, and easy for the great many others who were interested. One result is the hidden doors of many houses, so placed to avoid prying eyes. Another result was the mask and cape.

Yes, there is a ‘but’ coming. The book is all trip and no arrival. Though each theme is treated clearly and simply, this reader lost impetus. Without a sequence of events the reader has no characters upon whom to focus or chain of events to follow. Of course, the author’s choice to do that puts all the focus on the city of Venice and Ackroyd’s considerable powers of persuasion, and it kept me reading.

‘Doge’ is a dialect corruption of ‘duke’ and they come and go but none move the story on. Doges were invariably elevated at an advanced age, say seventy-two, and some then continued for another twenty years. There was an unbroken line of one hundred and twenty doges until Napoleon brought the Enlightenment on the bayonets of his army. The regime, in the terms of comparative politics, was authoritarian, oligarchic, patriarchal, and gerontocratic. That is for those who suppose labels are explanations. Napoleon, extracting a huge tribute from Venice, had the Golden Book of the Doges publicly burned. It was the genealogical register of the ducal families, the clan that sired the succession of doges, and its destruction completed the rupture with the past.

Venice was a republic; it did not have hereditary monarchs, though successful and powerful families strove for dynastic succession, and it did not have a feudal past in which a few owned the land and the landlord owned most people. The social strata were thus not the hard sediment they became elsewhere, but they hardened over the millennia. No gondolier ever became doge and no scion of the Golden Book ever poled a gondola.

Its foundation, existence, continuation, wealth, and stability depended on trade over the seas, and that trade required a great many skilled artisans to build, maintain, and repair the ships that were rented to merchants. The importance of these skilled craftsmen gave them more leverage in Venice than in many other comparable places. It is easier for the workmen at a single shipyard, the Arsenal, together to make their displeasure known than for an equal number of peasants scattered over vast estates to do so. See Gdansk in Poland for further confirmation.

The pages of the Golden Book represented about four percent of the population and the mercantile strata added another six percent, leaving the ninety percent out of the political, social, and financial elite. Those of the Golden Book tried hard to marry only within its own small ranks, and the merchants married their own kind when not trying to marry up. The total population in its prosperous times numbered about 100,000, more than it does today,

As with cities like Florence in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, the government of Venice was complicated and convoluted, by design, not by accident. When problems arouse a committee to act on it would be created and it would inevitably perpetuate itself in the first law of administration — goal displacement — revealed in 1957 by Philip Selznick in ‘Leadership in Administration.‘ There grew an encrustation of such committees with vague and overlapping remits, that never seemed to lapse. They often worked in ignorance of each other even when they had overlapping membership the law of secrecy applied. While laws were written, they were never codified and seldom promulgated and enforced only when necessary. It sounds very much like a university Department’s approach to self-government in the days when that was tolerated.

This open texture might seem to offer many opportunities for citizens to play one committee off against another, as is commonplace today in organisations, but not so in Venice, because the existence of most of these committees was secret, so secret that other committees with exactly the same terms would be created anew, and all of their activities were secret, too, including from each other.

Of course, there was no written constitution that spelled out anything. Some of that may remind a reader of working in a large organisation without an organisation chart, and no reporting. Yet everything is recorded. Ahem, see the passing remark above about a university department.

In a way, though prima facie more formal with its archive, it reminded me of the rule by talk in Colin Turnbull’s ‘The Forest People’ (1961) where every instance is treated as unique and talk, talk, talk until the antagonists prefer to give way than talk anymore, like those self-governing co-operatives in the 1970s where everything was done at all-staff meetings that went on, and on, and those who persisted eventually got their way. It was self-management by verbal attrition. Compared to this, McKinsey management looks better.

The Venetian mask a perfect metaphor for the pure city. It is ‘pure’ by the way because it had for most of its history no hinterland with apologies to Padua. It was all city and nothing else. While Florence had a rich agricultural land in its domain, where the Medici family raised beef cattle that still grace the plates of Italian cuisine, Venice had only itself and the lagoon.

In Venice care was taken to be sure that the archivist was either blind or illiterate so he could not read the files, unlike Connie in the John Le Carré Cold War novels. The files might be sequestered but Connie knew what was in them despite the sealing wax. The files might be altered but Connie forgot nothing. Corporate memory resided in one sodden pensioner.

That passing mention of Padua reminded me that Venice has another connection with Machiavelli. Cardinal Reginald Pole who broke with Henry VIII spent an exile in Padua where he became aware of Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’ and wrote a condemnation of it, though it is doubtful he read it. Since King Henry’s confident Thomas Cromwell had earlier spent time in Italy, Pole supposed that he learned his sins from Machiavelli. Association is poor proof of cause and effect, but this tenuous thread is woven into Hilary Mantel’s Tudor novels.

Today Venice remains a city of trade, and its trade is with tourists who come to it as if the whole city is a continuous exposition. Venice remains an entrepôt and the product it mow sells is itself. The tourist Venice, the Venice a tourist sees is Venice, he concludes.

While Ackroyd’s impressionistic tour refers to the mysteries and crimes of Venice the dedicated krimi reader turns to Donna Leon for detail.

Peter Ackroyd from the dust jacket.

Peter Ackroyd from the dust jacket.

This book is all trip and no arrival. It meanders here and there and Ackroyd is a superb cicerone.

Management the Sequel from the OSS

Sometime ago I promised a second instalment from the OSS manual for Allied sympathisers in continental Europe during World War II. For those who have patiently waited, here it is. The manual’s purpose was to show sympathisers how they could obstruct the Nazi war effort by gumming up the works ever so innocently without blatantly risking their lives.

One section was addressed to managers of companies, firms, and organisations from railroads to enamelware factories.

The items read like key performance indicators from McKinsey whose client list has included Enron and Swissair. Remember them?

(1) Demand written orders. Meanwhile, time passes and nothing is done.

(2) Misunderstand orders. Ask endless questions about minute details or engage in long correspondence about such orders. Meanwhile, time passes and nothing is done.

(3) Do everything possible to delay completion. Even though part of an order

may be ready, don’t deliver it until it is completely finished. Say that standards have to be maintained. More time passes.

(4) Do not order new raw materials until current stores have been exhausted, so that the slightest delay in filling your order will mean a shutdown. Why? It is inefficient to hold surplus material. Time keeps passing.

(5) Order only high-quality materials which are hard to get. Warn that inferior materials will mean inferior products. There is never enough high-quality material to go around so this order leads to an argument about priorities. These arguments never end. More time passes.

(6) In making work assignments, always assign the unimportant jobs first. See that the important jobs are assigned to inept workers. This is definitely from the McKinsey training course.

(7) Insist on perfect work in relatively unimportant products; send back for revision those products which have the least flaw. Approve other defective parts whose flaws are not going to be detected until use in the hope these products will fail at a crucial moment. Thus one appears fastidious but lets slipshod products through. Another chapter in the training manual, that one.

(8) Make mistakes in routing so that products are sent to the wrong place. A few well chosen typographical errors do the trick. If the reports have not been acknowledged, then one cannot proceed.

(9) When training new workers, assign training to those who have have no experience in the hope that they will give incomplete or misleading instructions. Ah, a favourite of mine. McKinsey all the way. The trainers have never used and never will use the system that they train others to use. A classic.

(10) To lower morale and with it, production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work. Reward the incompetent and punish the competent. This one has long a key performance indicator for some modern major managers.

(11) Hold meetings when there is more critical work to be done. Do so especially when the pressure is on, declaring that only by discussion can morale be raised.

(12) Multiply paper work in plausible ways. Start duplicate files offsite. Who can object to paperwork? Preparing, sorting, and filing takes time. Assign one of the best workers to this clerical job on the grounds that the paper trail must be perfect.

(13) Multiply the procedures and clearances. See that three people have to approve everything where one would do. Make sure it is always an odd number in the hope that there will be disagreement among them. Invoke our old friend standards again.

(14) Apply all regulations to the last letter. Work to the rule. Was for orders; show no initiative. The more obscure and less relevant the regulation the better. See standards above.

I never got the pellets.

I never got the pellets.

The OSS was the Office for Strategic Services, the forerunner to the CIA.

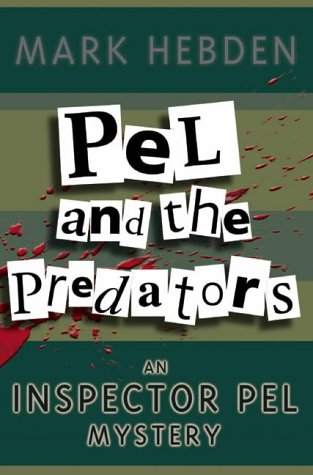

‘Pel and the Predators’ (2008) by Mark Hebden

Back in Burgundy with the irascible Evariste Clovis Desirée Pel, Inspector, Police Judiciaire. There are a score of these titles. He is short, with a few of remaining strands of mousy hair stuck to his bald pate, like sparse seaweed on a rock at ebb tide, chronically addicted to smoking two packs of unfiltered Gauloises a day, morbidly afraid of penury, socially inept, near sighted, a hypochondriac, and bad tempered for these and many other reasons. He takes out his bile on criminals who upset the idyll of Burgundy, from which he never willingly departs.

A dead girl who washed up on the distant Breton shore seems to have come from god’s country, Burgundy, and Pel makes routine inquiries that soon prove to be anything but routine. He reluctantly leaves Burgundy to travel to Breton to be briefed. When there, he felt he was standing at the edge of the world. Beyond Breton, beyond France, there is only blackness. His interview with the local detective, Bihan, is priceless. This Bretonnais is an imaginative type who has speculative backstories for everything and this elaboration drives Pel to his cigarettes and beyond. Eventually the point is made.

Back in Burgundy two teenagers exploring each other and a cave find another unidentified body, long buried there, and Pel has to identify it, too. In time these two strands come together, as readers know they must. The two dead women have something in common, though not what one might think. No spoiler.

These titles are police procedurals and there is much plod, and Pel has a team of officers, now enlarged because he has been promoted to Chief Inspector, which elates him, briefly, before he starts thinking about the greater responsibility, and then realises the promotion does not carry a pay raise, then the gloom and doom takes over. Some of the officers are bright, others are hardworking, and a few are lazy and stupid, and Misset is both, but somehow Pel has to work with them all, despite his recurrent urge to hit detective Misset with anything to hand if only to see if he stirs when struck. Pel is sure that Claudie Darel will one day push him out of his job. She is so smart, and knows how to use computers! He has learned to listen to her interpretations of facts.

Pel is some character. Somehow he has entered into a Faustian bargain with Madame Routy as his housekeeper and cook. He does not remember hiring her but there she is and he cannot fire her, since she seems to come with the house. In Burgundy she is the only person who cannot cook. After serving up indigestible stews each night, she plonks on the sofa and watches television at full volume. Ever the worrier, Pel suppose the vibrations from the telly will destroy his house all too soon, leaving him homeless as well as destitute. Meanwhile, he is sure he has some wasting disease.

Mark Hebden

Mark Hebden

Into his miserable existence, lightened all too seldom by the chance to bang up a crime, comes the widowed Madame Faivre-Perret, a very successful businesswoman, who seems to have picked him for her next husband, or so Pel fervently hopes when not terrified by the changes marriage would bring to his (dis)ordered existence, and how much it will all cost! Pel is an Olympic worrier. But when he is with her, at lunch, in the cinema, strolling the avenue, he feels ten feet tall and light as air! He even manages not to smoke for periods of ten minutes or more, though she has never said anything, he is sure she disapproves. When he is with her he even smiles! A Pel smile is a rare thing, indeed.

The only other light in his life is the Madame Routy’s nephew, Didier, with whom Pel sneaks out of Madame Routy’s baleful sphere to have snacks at the bistro rather than eat her sludge. How Pel’s shrivelled little black heart sings when Didier, now a teenager, says he wants to be a policeman, and then Pel starts to worry about all the bad things that can and do happen to flics. Can that man worry!

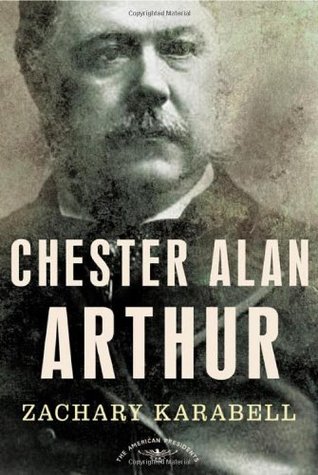

Zachary Karabell, ‘Chester Alan Arthur’ (New York: Henry Holt. 2004)

Chester A. Arthur (1829-1886) was 21st President of the United States (1881-1885).

Chet was born in Vermont and went west briefly to make his fortune before settling in New York City. He is often associated with the worst presidents in rankings by historians, along with Warren Harding, Franklin Pierce, Ulysses Grant, Millard Fillmore, and Andrew Johnson. Yet he is the president who signed the Pendleton Act into law, one of the landmarks of 19th Century politics.

His religious father was a devoted abolitionist and Chester, at his urgings, went west to practice law and to keep Kansas a free state. He found the wild west very wild and very far away and stayed only a few weeks before heading back. That was the first, and perhaps the last time, conviction governed his actions.

He made his way in New York by attaching himself as a loyal lieutenant to movers and shakers. He was personally sociable and gregarious, a man who positively enjoyed wiling the night away in men’s clubs where he got to know everyone and offended no one. While he was never anyone’s first choice for anything, no one was ever against him, ergo a reliable second choice at any time.

When the Civil War occurred he duly took to the colours of the New York state militia where he was appointed a quartermaster general by a patron. He secured this plum and cushy appointment, a long way from the cannon’s roar when hapless migrants were conscripted to die in the fields of Virginia, by the grace and favour of one Roscoe Conkling, who at the time and place was a kingmaker.

At the end of his military service, Arthur was a rich man. Our author has it that his law firm made a lot of money. Class, see if this makes sense: As quartermaster general he let contracts worth millions for food, weapons, clothing, boots, animals, fodder, leather goods, and more. Ever heard the word ‘kickback?’ Our author has not. Wikipedia is more suspicious and implies that Arthur used his position as quartermaster general in the most populous state to enrich himself.

He was not especially avaricious about it, but then he was not subtle either. Why bother when it was common practice to do so. Think Tammany Hall, and there is the picture, an alliance of Democrats and Republicans to exploit the government. Has a modern ring to it, doesn’t it?

Moreover this client passed even more ill gotten gains on to his patron, Senator Conkling, who was sometimes referred to as ‘His Lordship.’ Lord Conkling was avaricious and wanted all he could get, in part to bank roll his own plans for the presidency.

Arthur enjoyed luxury in food, furnishing, alcohol, and cigars which he generously shared with cronies in his Fifth Avenue hotel suite, which he kept even after marrying. Indeed the only point of tension with his wife was his persistent networking and socialising at the hotel night after night. She, Nell, died unexpectedly and young and left him a widower who continued the same life.

Conkling had him appointed Collector of the Port of New York by President Rutherford Hayes in a spoils deal. In return for supporting Hayes’s election campaign in New York state, Conkling got to allocate federal government position in the state. It was routine at the time for each new president to dismiss the entire workforce of the federal government and appoint anew those who had supported him, a changeover that might take a year to complete. Call these office seekers. This is the spoils system which had reached its peak by this time.

The Collector of the Port of New York was one of the most important positions in the country. Far more important than most cabinet offices or governor’s chairs. What was collected was tariffs on imports and taxes on exports, and the resulting revenue in New York consisted of more than half of the income of the federal government.

By some quirk of circumstance unknown to our author, Arthur and Conkling became ever richer during his tenure as Collector. Class, figure it out. Whatever, the brandy was French, the cigars were Cuban, the sofas were stuffed, the food was rich, and Chester Arthur moved in the world of J. P. Morgan, Jay Cooke, John Jacob Astor, John Rockefeller, Daniel Drew, Jay Gould, Charles Crocker, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Robert Risk, and other Robber Barons who ran the country while Hayes played at being president. Arthur moved in that world but he was not of it, a hanger on, not a scion.

There is silence about women.

Arthur was much whiskered, carefully coiffured, a dandy with expensive clothes and accoutrements. He liked all of these trappings of wealth, perhaps because they compensated for his lack of good looks, commanding presence, or manly experience in the Civil War or on the frontier. Reading of him I was reminded of a passage from ‘The Great Gatsby.’ Applied to Arthur it would mean he knew himself from the outside in. He wore expensive clothes so that meant he was an important man, and so on.

Arthur was one of the first customers for a new fangled designer who worked with metal and glass, named Charles, Charles Tiffany, who later became famous for his lamps.

After the Civil War the Republican Party, wrapped in Abraham Lincoln’s bloody shirt, was the dominant political force. The Democrats condemned for their association with rebellious southern states dominated a few cities in the north but otherwise were a spent force for decades. In the broad church of the Republican Party there were deep rivalries based on personalities, not ideologies or regions.

The most important one was between the ambitions of Roscoe Conkling and James Blaine of Maine for the presidency. These two were alike in their ideology-free ambition and unalike in every other way. Conkling was a bon vivant, open schemer, sybarite, aggressive, crude, and ill mannered. He fits the 7MATE demographic, a real man’s man.

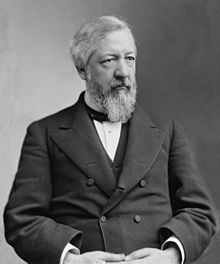

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling

Blaine was withdrawn, introspective, perhaps shy, and reflective, more inclined to read Caesar’s ‘Gallic Wars’ than to drink with the boys. More the SBS2 demographic. Their respective factions divided the Republican Party in half.

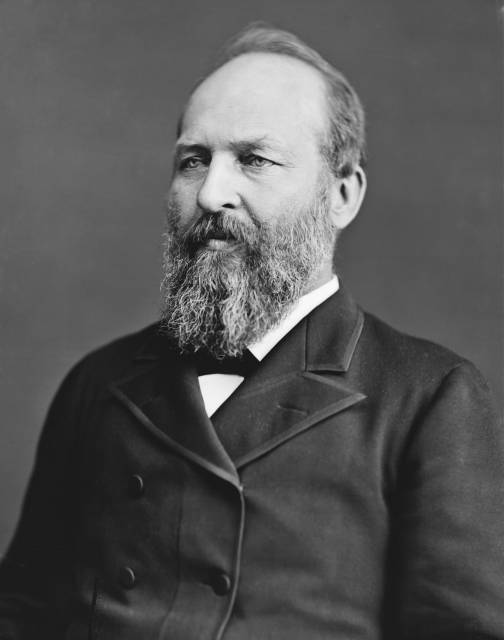

James Blaine

James Blaine

After a succession of Republican presidents, Grant, Hayes, and then Garfield, all Union generals, and the end of the military occupation of the South in the so-called Reconstruction when the seceding states laboured to pay taxes to settle the war debt, the Democrats came back to life. Off and on there was talk of a third term for Grant, which was new to me.

Conkling and Blaine both wanted the Republican presidential nomination in 1880, but more than that, each wanted to be sure the other did not get it. They undercut each other so effectively that James Garfield, who was not a member of either camp got the nomination. To win, he had to make peace with the two godfathers of the party and this he did by promising Blaine the office of Secretary of State and the say in a number of other appointments, which Blaine supposed he could use to plan a later push for the highest office, and by promising Conkling complete sway in New York state. The rivalry had become personal to Conkling and he would not serve in a cabinet that included Blaine he made clear, and New York was good but not enough.

Garfield pondered Conkling’s intransigence and then went directly to Arthur and offered him the Vice Presidential nomination in a move replicated nearly a hundred years later when Jack Kennedy went directly to Lyndon Johnson, no intermediaries, no consultation with trusted advisors. Arthur immediately accepted and shook hands with Garfield.

Conkling was outraged. Which was the greater felony? That Garfield went straight to Arthur without first asking Conkling if he could approach Arthur, or that Arthur accepted without seeking the approval of Conkling. The journalists observing all of this, often in the same room when the deals were done, supposed Arthur would not withstand the inevitable brow-beating from Conkling, and were thus surprised when he later appeared on the podium.

By the way Conkling was nicknamed ‘Lord Conkling’ and he liked that. He liked having graft monies delivered to him while sitting at his desk in the Senate like a lord receiving tribute from vassals

For the first time in his life as an ever loyal second Arthur defied his boss and told him so to his face. Conkling was apoplectic but when he calmed down later, he made the best of if because at least Blaine did not get the nomination and reluctantly allowed his New York state machine to campaign for the Garfield-Arthur ticket.

James Garfield

James Garfield

Garfield won and Arthur was installed as Veep, where his major duty, like all before and after him was to preside over the United States Senate’s meetings. This purely nominal duty turned out to be more important than any of the pundits expected for the Senate was evenly divided between Republicans, who had spent a lot of time fighting among themselves, and resurgent Democrats at thirty-seven each. Arthur had the deciding vote and he suddenly became an important person, not just a figure head.

Conkling’s influence nosedived from that day on. In fact, he soon lost his own Senate seat, so gross were his malefactions that even the New York legislators could not overlook them, and he was turfed. now a footnote of history.

Garfield took the oath of office and Blaine became Secretary of State. Three months after that Blaine walked with Garfield to Union Station to take the train to New York City when Charles Guiteau shot Garfield in the back. Two police officer grabbed Guiteau who made no effort to escape. Instead he told the officers that he had shot Garfield so that Arthur could be president, a line he stuck in his subsequent trial. Huh?

Arthur had nothing to do with any of this, that is absolutely sure, but Guiteau said it and more than once. Guiteau was a distant follower of the Blaine camp and he had formed a hatred of Conkling and his influence and he erroneously perceived Garfield to be Conkling’s catspaw. At his trial the defence attorneys argued that Guiteau was insane and that made about as much sense as Guiteau did.

When I learned of Garfield’s murder as a school boy the line was that Guiteau was a disappointed office seeker who took revenge on Garfield for not appointing him to a lucrative federal government office, and this line is still followed in the Wikipedia entry. There is truth in that interpretation because he had written letters asking to be appointed, but it is not what he said.

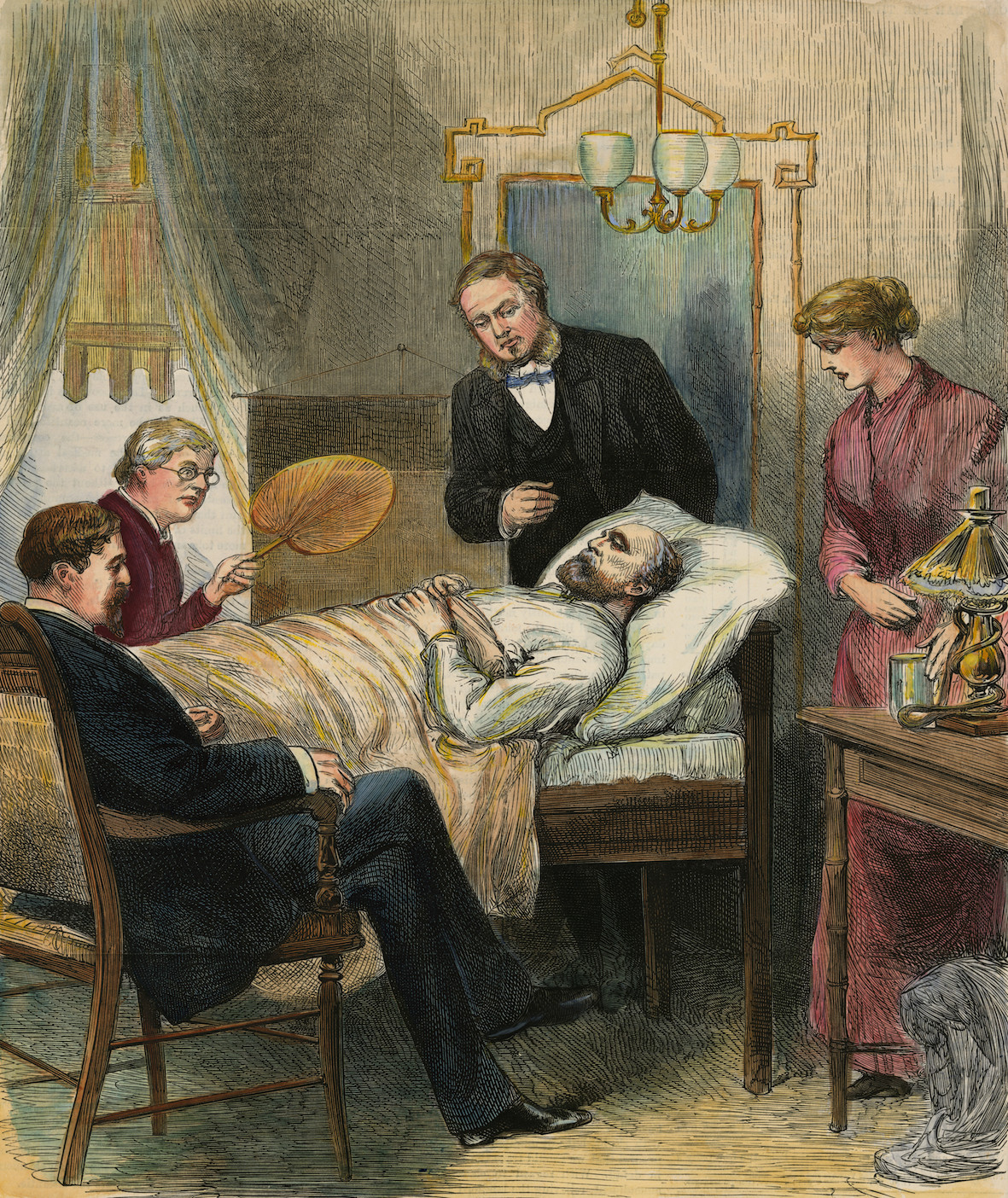

Arthur was in New York City when the telegram arrived telling him Garfield was wounded. A few minutes later a journalist arrived to tell him what Guiteau had said about him – Arthur. Gulp! ‘What to do?’ he must have thought. He went immediately to Washington to see Garfield, who was comatose and to see Garfield’s wife and family and offer sympathy and aid. He then retuned to New York City and stayed there Incommunicado for the three months that followed while Garfield slowly died.

His reasoning was that he best not appear eager for the office, and indeed, it seems he was not, and so he kept the lowest possible profile.

Garfield, wounded.

Garfield, wounded.

Another telegram arrived to announce that Garfield was dead. A local judge administered the oath of office and he was the twenty-first man to be president of the United States on 22 September 1881.

Guiteau argued his own defence, and his blame-shifting reminded me of some people I have worked with. First that Guiteau shot him is Garfield’s fault for walking to the station and so exposing himself to attack, that Garfield died of the wound is the fault of the incompetent doctors who did not save him, and that he died in New Jersey and so a D.C. federal court could not try him. Marvellous, but he was hung.

Arthur returned to Washington and took a hotel suite, leaving the Garfield family in the White House as long as they wanted.

As discrete as he was and considerate of the Garfield family, his incommunicado also meant there was no executive in the government for three months. This is a time when there was constant friction along the vaguely demarcated Canadian border, when European powers flirted with interventions in Mexico and Guatemala while the Indian wars were continuous and anti-immigrant riots were frequent in New York City and San Francisco. Though our author is silent on this I rather think James Blaine may have steadied the ship.

Arthur took the oath of office in Washington and made a short but apt speech some of which is quoted in this book as his ‘inaugural address.’ I balked at that word ‘inaugural’ because succeeding vice-president were not elected to the office of president and so do not give inaugural addresses.

No sooner had Arthur sat down in the big chair than all his drinking buddies, led by Roscoe Conkling, arrived, sat down, and put their feet up his desk, and called him Chet.

This worm turned. Arthur firmly directed them to remove their feet from the president’s desk and henceforth to address him as Mr President. Conkling choked on this rebuke but swallowed it. The others did as they were told. Conkling had expected to secure a cabinet appointment and he also expected to see Blaine dismissed. Neither happened.

At this point Arthur had one outstanding quality. He owned no one anything. No one had expected him ever to be president and so beforehand no one had bothered to extract commitments from him and his incommunicado had prevented later efforts at that. He was his own man. On the other hand, there was nothing he wanted to do, nor was he committed publicly to do anything. He stuck to that with one exception. In all of this there are many parallels with John Tyler who became tenth president.

Installed in the White House Arthur made his sister the hostess, and she set about redecorating the dump, encouraged by Arthur. Louis Tiffany came to the fore and made his reputation there. Virtually nothing had been spent on the White House since it had been rebuilt after the War of 1812. Congress repeatedly refused to fund anything for the president. Before it could be redecorated, much of it had to be rebuilt from the inside out and it was. In the aftermath of Garfield’s death Congress voted this presidential expenditure. The changes wrought as described in these pages sound grand, but all them were ripped out by subsequent occupants to keep up with the fashions of changing times and nothing is left of the Tiffany White House. It all went into the landfill.

An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

An example of a Tiffany screen like one installed in the White House.

The Robber Barons continued to rob. The army continued to murder Indians. Attacks on Irish immigrants on the East Coast and Chinese on the west were a daily occurrence. British and French interests continued to plot in Central and South America. More than once, shipping on the Great Lakes was interrupted by British patrols.

The federal government had grown during the Civil War and since then business had boomed. The coffers were full and the size of government began to diminish. Arthur ran a surplus and cut excise taxes.

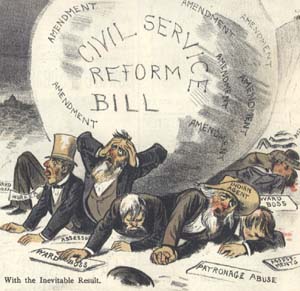

The spoils system, started by Democrat Andrew Jackson, had become a monster that consumed itself in the case of Garfield’s murder for the label disappointed office seeker stuck to Guiteau ever after, and the longstanding minority voices calling for a reform of the civil service were reinvigorated and now heard afresh. The example of the 1854 Northcote–Trevelyan Reforms in Great Britain the generation before was cited and speakers spread the word as did newspapers. The result became the Pendleton Act of 1883 which Arthur, a creature of the spoils system, signed into law, ending the very system that had made him. Ironies of ironies.

It slowly established civil service examinations for entry, seniority for promotions, ended levies of political contributions from salaries, and myriad of other things. Democrat George Pendleton of Ohio sponsored the legislation in the Senate. When its centenary came in 1983, I was sorry to see it pass pretty much in silence.

The Republicans had long been complacent of their domination of federal politics, but a rude awakening was delivered in the mid-term Congressional elections in November 1882 with Democrats sweeping into majorities in both houses. As a last ditch effort to redeem itself in the eyes of a jaded electorate the old Republicans who still dominated Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which had been languishing in committee for years, to claim the mantle of reform before the new members of Congress were invested in March 1883 and preparations began for the November 1884 presidential election.

One effect of the Pendleton Act was to drive political parties into the arms of business and later trade unions to seek money to campaign the length and breadth of the land. The toxic embrace endures today.

The immediate effect was to undercut Arthur’s support in New York which was entirely based on patronage. The Pendleton Act pleased no one. For the reformers it was not enough and for the spoilsmen is was too much. Thus Arthur alienated his allies and did not win any new friends to replace them. At last Blaine got the nomination for 1884.

Arthur’s high living had also caught up with him in a combination of internal ailments which left him weakened. He died shortly after leaving office at fifty-seven.

Zachary Karabell

Zachary Karabell

This was an easy book to read and it is sprinkled with insights and some very well turned phrases. It is odd that the author seems deliberately to turn away from the obvious fact that Arthur systematically used public office for his own private enrichment. Yes, others, too, did so but they were not president and he was and they are not the subject of this book and he is. It is also disconcerting to see several references to Thomas Reeves, ‘Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester A. Arthur’ (New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975) as the authoritative biography. It made me think I should have been reading that. As is the case with books in this series, this one is not based on primary research but rather synthesises existing biographies, and so it remains at a distance from the subject and a reader feels that.

‘Morgue Drawer for Rent’ (2012) by Jutta Profijt

This is the third instalment in this mile-a-minute series that combines science and ectoplasm. Herr Coroner Dr Martin Gänsewein remains saddled with Pascha, late car thief extraordinaire and murder victim. Of all the cadavers in all the pathology labs in all of the world Martin had the bad luck to slice into this one cadaver, complete with a ghost, who can communicate only with him, and who does, often.

They are the odd couple to end odd couples. Pascha, phantasm though he be, retains his lowlife interests and four-letter word vocabulary, while Martin is a round-shouldered, mumbling, introverted, shy, rumpled, near-sighted, hyper-conscientious scientist who eats lettuce leaves, flosses between his toes, and does not drink alcohol. ‘He calls that life,’ says Pascha with a snort.

In between solving crimes in the first two books, Martin spends much time, effort, and money in the vain attempt to screen out Pascha. Microwave transmissions disrupt Pascha’s atoms, he discovers, but harnessing those at home proves to be challenging and impossible at work. Having a ghost shouting in his mind has disrupted Martin’s slow and uncertain love-life with Birgit, and the fallout has confused his colleagues and friends. At times Martin oscillates between the hysterical and the comatose, caused as we and he know by Pascha’s hectoring.

Pascha can also interact with the voice recognition software of Martin’s computer which he uses to write an account of his adventures that he submits by email to a publisher, without Martin being the wiser. Pascha’s career as a writer is one theme in this romp. He is delighted to be published but angry that the work is called fiction!

Another theme is the new manager of the Forensic Institute of Cologne who is an MBA, charged to increase efficiency and cut costs to the bone. That he knows nothing of the legal environment in which the Institute works, that he cares nothing at all about pathology, that he knows nothing about preserving police evidence, these facts do not cause him to miss a beat. He simply delegates responsibilities to others while undercutting and undermining them. Ah, corporate life! The key performance indicators click over. At least he is no hypocrite, he does not mouth platitudes about the staff, he simply shafts them, belittles them, and shows open contempt for them. A refreshing honesty in that.

All of that is credible and the author must have worked in a large organisation where she observed this kind of McKinsey-speak management.

In no time at all the new boss, whom one of Martin’s colleagues nicknames Piggy Bank, is renting out the morgue’s facilities to funeral directors, who come and go at all hours of the day and night. Soon enough, things go missing, like the body of a murder victim. In the subsequent search for a scapegoat, Piggy Bank’s eyes land on the inoffensive, compliant, and meek Martin. He accepts his fate with resignation, while Pascha is outraged!

Meanwhile, Herr Piggy Bank is completely without scruple or shame. See, I said realistic.

Another of his innovations is to charge the police for consultations with the pathologists. In no time at all Martin has violated Piggy Bank’s many new rules and is dismissed. That frees him to probe more and he does but only because Pascha drives him to it.

Meanwhile, Pascha has stumbled onto the reason for the body snatching, and alerts Martin. It is more complicated than that, of course, because Pascha has fallen in love with Irina, a doctor, and Birgit has laid down the law to Martin about his strange lapses (when Pascha is yelling at him). On top of the that Cologne is hit by a relentless heatwave that makes everyone’s life a misery.

Pascha’s efforts to communicate his feeling to Irina are … extreme. The incorporeal and corporeal just do not mix. As always, his efforts backfire on Martin.

Piggy Bank is a marvellous character, the very model of modern major manager. He is tanned, even in winter we are sure, taut of skin, brisk of manner, clear of eye, devoid of conscience, free of knowledge, completely teflon, seen only when he wants something, totally indifferent to the staff who are only costs, obsequious to his superiors, haughty to underlings, tasseled of shoes, blazer-wearing, and he speaks but key performance indicators, single-mindedly pursuing his own advancement. Sound familiar?

It all comes together, and it all comes out in the wash. The plot is ingenious and kept me guessing until the author produced the rabbit. Then, ‘Voila!’ It all made sense. Several blue herrings added to the misdirection.

Jutta Profijt

Jutta Profijt

Not all the loose ends were tied. When Martin, on Piggy Bank’s orders, refused to talk to police officer Jenny, she storms off to have it out with Piggy Bank, and….. I don’t know.

The self-deprecating joke the book ends with is delicious. Toilet brush indeed!