A Walter MItty story set in contemporary Montréal. Jean-Marc lives a downward spiral in a world that is collapsing all around. To escape he daydreams, nightdreams, afternoon dreams his life away, enduring an impossible job, a loveless marriage, a daily trek to be demeaned at the office while being incapable of assisting any taxpayer who comes to him for assistance. It is a well worn franchise, this story but it is handled with vigour and imagination. If the whole does not compute, many of the parts are great fun, some of them instantly recognisable.

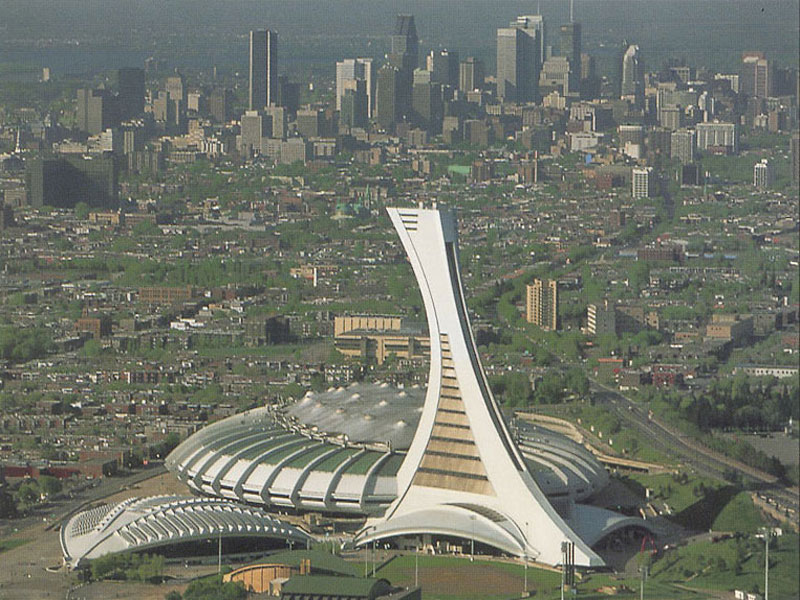

For instance, the committee meeting of ten to explain to Jean-Marc that ‘negro’ is a non-word in his first official disciplinary warning. The elaborate methods of the smokers to avoid the anti-smoking patrols. Yes, security guards with dogs on anti-smoking patrols. Then there is the singular Montréal touch, that Olympic stadium white elephant. Though no government in fifty (50) years has a found a use for that monument to the ego of Mayor Jean Drapeau, Denys Arcand has: government social services offices.

Why not, a billion tax dollars went into that monstrosity at the end of the metro. It is has been cited in every other Olympic bid as an example of what not to do.

Of course the functionaries have little time to deliver social services since they are constantly in meetings to hammer each other very politely with a host of conflicting and contradictory rules, to be motivated even if depressed and dispirited by Humour Quebec, to be trained in the latest trivial tweak to the meaningless rules, planning how to cut the next budget, and scheduling the next meetings. See, I said instantly recognisable.

His daydreams about revenge on his line manager and the supervisor….

The prince’s minions at work.

The prince’s minions at work.

Well that prince of equatorial origin is famous for his cruelty. Seeing a Roman emperor dragging on a cigarette, that is worth the price of admission.

His imaginary girlfriend’s anger at being the dream girl for such a loser, ouch, that hurt! But she did not seem to mind his other fantasy women.

The harem.

The harem.

The high-powered wife is a caricature, to be sure, but then so is everything and everyone else. The news on the radio, television, and newspapers is one downer after another. Everyone wears surgical masks in public because of an unfathomable disease that the authorities cannot control. The commuter train, which breaks down everyday, is repaired by the driver with a sledge hammer. The metro is packed with unpleasant people. Criminals with guns are released on technicalities that no one understands. Gangs roam the streets at night. The sky will be falling soon. This is not a Montréal for tourists.

Perhaps thanks to a chance meeting with another fantasist, and more importantly the death of his mother, Jean-Marc is jarred out of his mind world. He leaves home just when his wife returns. I started to type ‘estranged’ wife but their relationship is not close enough to become estranged. He banishes his dream girl with the recriminations of a long married couple. By the way the earlier shower scene with the reference to American film classifications lets us all in on the joke.

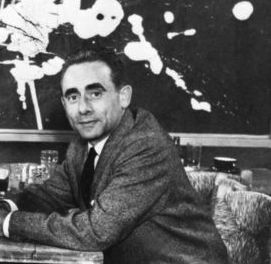

Denys Arcand gesturing. A great talent, this one with a string of thoughtful and memorable films including ‘Jesus of Montréal,’ ‘Decline of the American Empire,’ and ‘The Barbarian Invasion.’

Denys Arcand gesturing. A great talent, this one with a string of thoughtful and memorable films including ‘Jesus of Montréal,’ ‘Decline of the American Empire,’ and ‘The Barbarian Invasion.’

Recorded from SBS and watched later. The title ‘L’Âge des ténébres’ is literally the Dark Ages, but for reasons best know to themselves the SBS producers called it ‘Days of Darkness.’

‘The Imitation Game’ (2014) at the Dendy Newtown

Bletchley Park first was unknown, then a curiosity, a historical drama, and now a fantasyland.

Bletchley Park, now open to the public.

It remained secret for most of the Cold War, then a little information became available in the 1960s, then a lot more in the 1980s, and now the facts no longer constrain the story teller. ‘Enigma’ in 2001 was one take on it, a drama with a tortured performance from Dougray Scott and Kate Winslet playing against type. It was perplexing and rousing.

In 1968 Dirk Bogarde ran the show in ‘Sebastian’ with understated panache.

’The Bletchley Circle’ has also been on the small screen, which after a great start descended to the average, emphasising special effects over intellectual content.

We dithered about going to ‘The Imitation Game.’ Seeing man’s inhumanity to man, well, we could see that on the television news any day. Huh? The publicity emphasised the abuse of Turing for his homosexuality; no doubt this was done to martyr him, but it put us off. For a while.

Bletchley Park, I had to see that again. Nerds winning the war! Near sighted, stoop shouldered, shuffling wallflowers with bad table manners, I could identify with them! Sorry Brad Pitt but you are not in my league.

The importance of codes and decoding has a long history to be sure. There is that Zimmerman telegram of 1917, a coded German message to Mexico that was intercepted and decoded and gave the United States a push into the war. More on the Zimmerman letter at the end. Read on.

To compare ‘Enigma’ to ‘The Imitation Game’, a few points standout. ‘Enigma’ showed Bletchley Park to be the gigantic factory it was, employing in 1944 about 12,000 people. The Bletchley Park’ of ‘The Imitation Game’ is confined to less than a dozen people with a few CGI backgrounds. In ‘The Imitation Game’ Commander Alastair Denniston is a foolish martinet, played to a ‘T’ by Charles Dance, but in fact he was the one who decided very early that code breaking in this war required mathematicians and engineers. In earlier years, decoding had been the province of linguists and translators. Not this time. Likewise, running crossword puzzle competitions to recruit personnel was his, not Turing’s, brainchild. Nor do I think the beard is right for 1942. None of the pictures I could find show him with a beard in the 1940s.

Colossus was indeed a digital computer but it was neither designed nor used by Turing but by others. Turing devised and built another device, but the film is ‘based on a true story’ so the slather is open.

Many reviewers have focused on Turing’s homosexuality, and it certainly was the man. For the one-eyed there is not enough emphasis on that, no doubt, but to this viewer it seemed partly anachronistic, i.e., the references were too explicit for the time when homosexuality was the love that did not (dare) speak its name. The very word itself in 1942 would have not always been understood. Having said that, there was plenty of emphasis on it, though Turing suffered also from autism, and code-breaker he might be, but he could not see double meanings in conversation, a fact that is very nicely presented in the scene in the pub. There was also paranoia in the mix.

There is no historical reason to believe that Turing made any decisions about the use of the material. Disclosure by using the intelligence, this was a command decision made at the very top. though Turing may have realised the implications of acting on the information but it hardly seems consistent with his complete self-absorption most of the time. Making a member of the inner circle, who apparently does nothing, a relative of a sailor on a convoy was a very midday soap opera touch. Every ship had brothers and sons on it, a good many wives, sisters, and daughters, too. ‘Enigma’ plays this straight and the result is all the more powerful when the senior naval officer implicitly orders his men to their deaths for the greater cause.

It seems very unlikely to me that a one page letter from Turing to Churchill would have uncorked a £100,000. Perhaps Leo Szilard, Churchill’s science advisor, interceded, but we will never know in ‘The Imitation Game’ where Turing is the singular Atlas on whose shoulders the world rests. On the same page the confrontation after the door is kicked in seems almost childish in its resolution where the messenger from the Home Office without word of dialogue has the authority to nod to a six month extension but mutely accepts a one month edict instead. Hello! It does not work anything like that.

Turing did write to Churchill at one point to ask for more clerical staff, and Churchill did reply immediately for ‘Action this day.’ Based on a true story they say. Hmm.

I found the chopping back and forth through time from 1928 to 1942 to 1955 confusing and distracting. The only reason the schooldays of 1928 were there in the end was to explain the name Christopher on the last contraption Turing built. It was unnecessary to the story.

Benedict Cumberbatch strives to save the day and nearly does. He does not need that backstory of 1928 to be confused, arrogant, inept, autistic, brilliant, frightened, determined, lost, secretive, brassy, paranoid, unpredictable, lonely in a crowd, and more. He did them all by turns and at times a couple at once, riveting.

Alan Turing

The female lead by comparison goes through the motions without ever quite inhabiting the part, made more difficult for being underwritten. She becomes nothing more than a plot device. Joan Clarke in fact became Deputy Head of Hut 8 which housed the first Colossus, but you’d never know it in ‘The Imitation Game.’ And she did not secure this position by patronage from Turing, to be clear. By the way she wore glasses, as did Kate Winslet in ‘Enigma.’ Hooray for Four Eyes!

The idea that the air is full of secrets is quite an idea and I wished the film makers had scrapped the CGI warfare, which was uniformly poorly done, for something creative. Would there not be a way to show those messages passing through the air like tracers and being netted at British listening stations. Now that would excite any viewer. Maybe something like this map of transponders on European air traffic.

There are several scenes of Turing running and he was a Olympic class distance runner, who failed in an Olympic try out because of an injury. One of his many personal eccentricities was to run to London for meetings, carrying a back pack with clothes. Another was to chain his perfectly ordinary tea mug to the radiator.

The imitation game is still a test for artificial intelligence pretty much as described in the police interview room where Turing breaks the Official Secrets Act he signed in 1939 to tell the plod all.

The Zimmerman telegram was decoded and acted upon in 1917 by a team that included Alastair Denniston. A feeble effort was made to hide its source, and the Germans continued to use the same code. More intelligence from broken codes was used, and the German continued to use it. Even when the pretence of hiding the sources was dropped, they continued to use it. Why? Because it was a German code and so it was the best. It was unbreakable, despite the evidence that by the middle of 1918 the Allies were reading every radio message. See Barbara Tuchman’s marvellous book ‘The Zimmerman Telegram’ (1985) for tale of his Teutonic arrogance and folly matched only by that of the United States.

‘La Boîte Noire’ (2005)

Another little gem from SBS Television, this one from France.

A la suite d’un accident de voiture, Arthur est plongé pendant quelques heures dans un coma. Durant sa phase d’éveil, dans un délire verbal, il exprime des phrases incohérentes qui trouvent leurs racines directement dans son inconscient. A son réveil, il est face à une curieuse énigme : Que faisait-il la nuit sur cette route, proche de Cherbourg?

The title is perfect, once you get it, and as soon as it is said it clicks. The Black Box, c’est toi. Nice, very nice. The layers of reality and illusion are nicely done and the preoccupation with the brother begins to seem strange, and it is.

At first it seemed to be the story of an amnesiac who sets out to investigate himself, to recover his memory, as in a detective story, but it drifts away from that to science fiction or fantasy with the masked ninja. Even so, compelling viewing. It remains a study of unresolved guilt and obsession unleashed. Perhaps the larger purpose is to challenge the borders between reality and illusion but it does not succeed at that.

Juan Garcia’s many transformations from bland, sad, angry, confused, disoriented, lost, forgiving are worth the 90 minutes. He is in virtually every scene and carries the film. He is a superb actor and when we watched another SBS movie later I missed his depth, variation, and intensity compared to the callow actors in the next film who were so clearly going through the motions. Garcia believes what he is doing and makes the viewer believe it, too.

I recorded it because I saw that Richard Berry was the director and that it featured the ever versatile Juan Garcia.

Garcia I got to know when he played Adamsberg in a film based on one of Fred Vargas’s superb novels, altogether very fine that one,’Pars vite et reviens tard’ (2007) from ‘Have mercy on us all.’ That title in French is an idiom like ‘scoot and come back later’, and has nothing to do with the title of the book which is the same in both languages. Go figure. I cannot think of English equivalent to this idiom, though no doubt there is one I just cannot recall.

Richard Berry took his place in my mental pantheon with ‘C’est la vie’ (1990), another gem, directed by Diane Kurys, in which he played one of the parents, with only one scene but that was cut glass. I have kept my eye out for him ever since. He has a long list of credits including “Tais-Toi’ (2003).

The tag line on the poster above, ‘it is necessary to forget’ is perfect. It also reminds me of that old maxim that successful people have short memories. They forget their failures and mistakes and keep going. Selective memories is more accurate, but the point is not to dwell on mistakes, errors, and failures, and to keep going. When you quit, the others win.

I see that on the IMDB ‘La Boîte Noire’ scores a miserly 5.8/10. Well that confirms a conviction that most people do not recognise quality.

‘Double Entry’ (2012) by Jane Gleeson-White

The subtitle of this book is ‘How the Merchants of Venice created modern Finance.’

Yep, this is a book about the thrills, chills, and spills of accounting and accountants, the thrills of receipts, chills of ledgers, spills of debits, and that is just the beginning! Economics is the dismal science, and accounting is its dreary cousin.

In 1986, according to my notes, I read Fernand Braudel’s ‘Capitalism and Material Life, 1400–1800’ in three magisterial (a code word for large and long) volumes. Braudel asserted in passing that the invention of double entry bookkeeping generated capitalism in Europe, first in Italy and then as Italian banks expanded northward to Amsterdam in Europe as a whole. At the time, I asked an accountant upstairs what double entry bookkeeping was, and he invited me to attend his twenty-seven lectures in Accounting 101 to find out. Some people always want to start way back at the beginning.

I tried again a few years later when I asked another accountant, who answered, in exactly 50 minutes, a lecture. That was simultaneously TMI + NEI or Too Much Information and Not Enough Information. None the wiser, my interest withered. But the ground was covered, as lecturers like to say.

Then one day I came across this title. The blurb promised that it would reveal all about double entry bookkeeping is. I took the bait! Who wouldn’t? Here is what I learned.

The Crusades created first mass tourism through Northern Italy which bought vastly increased demand for goods and services. Enterprises flourished to take advantage of the market opportunities these tourists offered, and so Italy has since remained. The Crusaders, those that came back, brought many things with them apart from saintly shin bones that they acquired from enterprising Arabs, they also brought back Arabic numbers.

Venice made sure it got a piece of the tourism action both ways, and the tourist boom it got put it on the map to stay since then.

Mathematics evolved thanks to those Arabic numbers, though it was resisted by the Catholic Church which saw evil in Arabic numbers. Multiplying and dividing was regarded as black magic. Sounds like an analysis by Fox News today. Ignorant and proud of it!

Though very Catholic, the authorities in Venice were pragmatic enough to tolerate Arabic numbers, despite papal fulminations. (Presumably some gold changed hands to buy the silence of the local prelates.) Indeed, Venetian authorities encouraged sound book-keeping, the more prosperous businesses are, the more taxes are due; the more accurate records are kept, the easier it is identify the taxes that are due and collect them. On this reasoning, the Venetians also invested in education! Hmm, has not quite caught on that one. Smarter, more well informed people make better use of their resources and opportunities to solve problems. This is still a new idea to some governments today, it seems.

Moreover, the Venetians licensed the publication of books about mathematics that spread the word through the Mediterranean world. Indeed because of its relative tolerance and stability it became a centre for book publishing as Amsterdam was to become later. Some of the earliest mathematics books published in Venice were applied mathematics aimed at book-keeping, says our author.

After all that background, what is double entry book-keeping? Good question, Mortimer! The essence is that each transaction is recorded in two entries, one called ‘credit’ and the other ‘debit.’ Wake up! ‘Credit’ and ‘debit’ are not used here in their ordinary meanings. (Those conscripted to use Spendvision will realise that there is nothing intuitive about accounts.)

Prior to double-entry book-keeping (hereinafter, DEBK) merchants, nobles, tradesmen, households did not keep accounts of any kind. I expect most of us still run the business of our daily lives like this.

Those that did keep records before DEBK, made notes on scraps of papers as reminders when something had to be followed up.

Most of us do a little book-keeping, say when keeping receipts for business expenses to submit for reimbursement from the firm, or to support business deductions on income tax. Either when submitted or at the end of the tax year we categorise and total these records. That is a primitive form of book-keeping. Corporate credit cards perform some of this record keeping for business expenses.

Before DEBK, the more careful merchants, especially those with larger volumes of transactions, began to write them down in a single list, e.g., of things bought and things sold. A month later it would be hard to find a particular transaction in that list, undifferentiated and without annotation. First came annotations which took the name ‘memorandum.’ These memos were sorted and entered again in a journal (a term still used in accounting), and finally in a ledger.

DEBK nests in a ledger with a T making two columns that are still to be seem in ledger books at Officeworks, Staples, or OfficeMax.

If I have $500 in my pocket then I have a debit against my capital of $500 and a credit in cash of $500, ergo two entries.

I know there is a lot more to it, but like all those accounting students I find it hard going.

The book goes on to claim that DEBK is the key to the whole of capitalism because someone said so. A lot of someone’s are cited, but…. Hold on! Slow down! Wait a minute!

The author shows that many people talked about and praised DEBK from, say, 1500 on, but not once, not ever does the author show that it improved business practice, was associated with greater productivity, led to more revenue for Venetian purses or anyone else’s. In short, there is nary a (factual) word about impact. It is all very Cultural Studies (a phrase I always shudder to hear, let alone type) to suppose that talk is reality and that reality is but talk. (Didn’t those Cultural Studiest ever mean a Lying Blackfoot? [You either get it or you don’t.]) Everyone praises Christianity, but it is seldom practiced with the fervour with which it is praised, even by those who praise it most, i.e., members of the Tea Party.

To a jaded reader (me) the best chapter then is the penultimate one on accounting scandals. Whew! What a list: Enron, Royal Bank of Scotland, World Com, HIH, One.Tel, ABC Learning, and that is just in the very recent past with an emphasis on some of the small potatoes of Australian examples. Of course when the potatoes are all one has, they are not small. Despite Australia’s sorry experience, it has more accountants per square dollar than either the United States or Kingdom (p. 153).

The author carefully alludes to the string of examples of accounting firms, which trade on their reputations, signing off on accounts of such corporations as those above a few days before the house of cards falls, and much to everyone’s surprise the piggy bank is empty, including the pension fund.

It does make a punter like me wonder what the point of it all is. (Yes, I thought of Foucault.) Have rules become so complex that a clever and determined villain can use them to hide the trail (in some cases for years)? Do more rules create more loop holes, black spots, grey areas, and trees to hide the forrest and just generally make it easier to play hide-and-seek?

For a couple of years I served on an Institute of Charted Accountants committee that enforced professional ethics on its members. The rigour of the proceedings of this committee, the take-no-prisoners attitude of its professional members (I was a lay member) was all very impressive, but all the cases (documented sometimes in hundreds of pages) were about the date of a membership re-newal to the Institute or something else on that level. Was the postage stamp correctly squared on the envelope, is what I silently thought sometimes. (Yes, it was that long ago that postage stamps were relevant.) Such tiny ants were destroyed with titanium tipped warheads! Ouch! Inevitably, the accountants involved were sole practitioners who were humbled before this pitiless tribunal. Meanwhile, the major accounting firms in the same building were signing off on the accounts of the likes as those above. Go figure.

In this world, the mud seldom sticks. The author describes some of the subsequent careers of many of the major players in the scandals above. At a corporate level the accounting firms that approved the accounts of such corporations change their logos and web sites, a few partners take the money and run, oops, retire, and the firms continue to dominate not only the market for accountants but also for consultants to government and more. One fears the same people who brought us the last corporate collapse are now happily advising governments on the next one. No mea culpas can be heard.

Like tools, rules can be used for good or ill to be sure. But independent audits are supposed to deter and detect some of the ill. Maybe they do, but that does not make the headlines.

Tidbits, there are a few. The CEO of the Royal Bank of Scotland CEO presided over the creative accounting that led to its near-death experience got a golden parachute of £16 million paid for by the ever generous British taxpayers (p. 197).

The high and mighty behemoth Arthur Andersen started in 1929 as a cleanskin firm which would ferret out cheats, and died in 2002 of the same poison. Well do I remember once getting told off by a very proud Andersenian about the irrelevance of ethics education in business degrees.

By the by, Enron started in Omaha where it trod the straight and narrow, but when it moved to Texas, well it crossed more than a state line, thus confirming some deeply held prejudices of mine.

Jane Gleeson-White

Jane Gleeson-White

As to the book, there is too much background and too much repetition and not enough focus or exposition of essence of double-entry to my mind. I still not sure what it is, so don’t ask.

‘Copyright’ (p. 78), no I do not think there was any intellectual property, but rather a license that permitted publication (i.e., passed by the Church censor and the Venetian censor). Copyright protecting the author’s intellectual property is centuries in the future.

A word is used that I cannot find in a dictionary: ie (p. 94). Even the spellchecker thinks it should be i.e. but not in this book.

There is a reference to Aristotle reviling interest on borrowed money but no text is cited (p. 96).

‘The Monogram Murders: The new Hercule Poirot Mystery’ (2014) by Sophie Hannah

First things first, Agatha Christie is the Nile River of murder mysteries. Her flood of stories has enriched the soil for others, imitators, rivals, critics, competitors, parodists, and those who try their own hand. Miss Marple, Tommy and Tuppence, and most of all, the one and the only Hercule Poirot.

Agatha Christie, who said the secret to getting ahead is getting started. Amen!

Agatha Christie, who said the secret to getting ahead is getting started. Amen!

Poirot revivus! He died in ‘Curtin’ published in 1975 but written thirty (30) years earlier and cached.

The Christie family has guarded her heritage with care. No cheap knock-offs, no tee-shirts, or coffee mugs, no theme tours of St Mary Mead.

Only occasionally have the Christies permitted films based on the novels, and according to the scuttlebutt amongst us krimieologists, the family has not been pleased by some of the movies. Ergo the exacting standards the Christies asserted for the Davis Suchet television series, and we viewers are grateful for the meticulous attention to every last detail, which is just what Poirot himself would do. As he says in this tribute volume, no detail is too small to be important. Only when seen in the proper context can the importance of a detail be determined. Order and method, that is the Poirot way.

This title is a Christie-inheritors approved work that is set in the London of 1928. There is neither war nor depression, yet. Money flow freely.

This Poirot is certainly Poirot. He is meticulous, scrupulous, fastidious, observant, perspecatious, easily irked and rather irksome himself. The little mustachios seem to twitch at times. The grey cells are evoked. But more important is the inner man who is compassionate and who detests the evil we do to each other without quite detesting the evildoer, or at least not in all cases.

Each character is well etched and distinguished, though I missed Captain Hastings, here replaced by a fledging police officer name Catchpool. Fee in the coffee shop is a winner and I am sure most readers want to hear more from her. Even Poirot is moved to remark on both her powers of observation and grasp of context, if lacking his unrivalled mastery, as he avers.

There is much to like in the book. If I have to make a criticism I would say that I found the repetitive dialogue as each character tells the story, and some of them tell it twice, and Poirot re-tells it again and again, tedious. We need more movement and activity. The author seems, however, to prefer talk, talk, talk, and more talk. All too much like a David Mamet play where the characters talk each other to distraction and the audience to sleep.

The plot, of course, is convoluted but that is to be expected, though why anyone would try to outsmart Hercule defies belief. Does not everyone know by now that he is world’s greatest detective and is never ever wrong! He certainly does his part to spread the word. However, the plot did not quite deliver the goods. There was a lot more trip than arrival, despite the many repetitions. Perhaps that is a quibble. But the monogram seems to have been there just to confuse things at the beginning, and some of Poirot’s revelations would have been trumped by police post-mortems if the wet-behind-the-ears Catchpool had followed procedure as per many other Agatha Christie stories.

Blue herrings there were a few, and some were never resolved on my reading. Rafal and that laundry cart in the front lobby is made much of when it occurs and referred to again at least once as a lead, and then never mentioned again though Rafal reappears. What did I miss? The hotel manager is such a larger than life character for the first half of the book and then all but disappears. When a character is given so much attention, the reader concludes that the character figures in the plot and is not just wallpaper.

There is an accompanying web site with some mini-videos of the books characters and episodes. Although the ones I watched did not jibe with the novel, so I stopped.

Overall, it is very good to see that Hercule Poirot is back among the crimefighters. Thanks to all involved in the resuscitation.

Sophie Hannah

Sophie Hannah

Sophie Hannah has a long list of titles and I will certainly make a note to try one of them.

Georges Simenon, ‘The Two-Penny Bar’ (1932)

Maigret did not leap full grown from Simenon’s brow, as Athena did from Zeus. No, he developed overtime. This is one of the early titles.

It is high summer and Maigret wanders around, seemingly with few responsibilities. Madame (Louise) Maigret has gone away for the summer to visit her sister in Alsace, and in her absence he haunts restaurants and bars, and falls in with the crowd at the ‘Two-Penny Bar’ along the Seine in the Ile de France. When a crime occurs under his nose, he muses quite a bit and asks a few questions, but keeps drinking with the crowd, whose members do not seem to mind having a police officer in their midst.

His rapport with the English ex-patriot James is engaging. James keeps popping up and it is evident that he is part of the plot, despite his detached manner.

The sketches of summer heat and blinding light along the Seine make a reader feel warm.

Madame Maigret is, as ever, patient, and long-suffering in silence.

The published title in 1932 as ‘La Guinguette à deux sous’, it was translated into an English edition years ago as ‘The Bar on the Seine.’ A ‘guinguette’ is a small, rustic bar with music and dancing, often to be found in the countryside. Perhaps the equivalent English term is a tavern – nothing fancy and not much in the way of food. ‘Roadhouse’ might also apply.

In the French ‘deux sous’: one ‘sou’ + one ‘sou’ = two sous.’ There were 100 ‘sous’ in a franc in those days. A ‘sou’ bought very little, even in 1932. Hence the idiom, not worth a sou (‘ne vault pas un sou’).

For reasons best known to the translator, and I suspect even better known to the publisher, it has been rendered as ‘two-penny.’ Yet later we read of francs. How many pennies to a franc, one wonders.

‘Two-penny’ is not an English idiom, per my web investigation. It seems to be idiosyncratic, fabricated for this title. That is bound to communicate to the reader, eh!

Why do I emphasise this usage by devoting space to it? Because the justification proudly displayed on the Penguin web site for these new translations of the Maigret books that it is marketing is to offer more literal, more authentic translations closer to the original. We can be pretty sure no one along the Seine in 1932 was paying with pennies. One may also wonder about the business sense of deprecating one’s own previous products, too, because after all Penguin editors commissioned and published those earlier translations. If they were as bad as now claimed, does that not undermine confidence in the present crop? Well it does when pennies go into francs. What will future editors at Penguin say about these translations?

I am equally dubious about the woman’s bathing suit that graces the cover of the copy I have. I rather doubt it was worn in 1932. Most swim-ware at the time would have been made of wool, I suspect, and have likely been more modest than the red number on the cover. ‘Fuzzylizzie swimwear’ confirms my hunch.

‘Parades and Politics at Vichy: The French Officer Corps under Marshal Pétain’ by Robert Paxton (1966).

In 1931 the French army was the largest, best trained, most modern in equipment with a wealth of strategic intelligence in a large and able general staff joined to the leading airforce of Europe and a large navy with newer and more powerful warships than England or Italy. In addition the French Army had those kilometres and kilometres of tunnels, bunkers, turrets, gun emplacements, tank traps, endless buried telephone wires and underground cities of the Maginot Line. To members of the general staff of Germany, of Spain, of England, and of Italy, France was an impregnable fortress. Moreover, it had an even larger colonial army spread around the globe from New Caledonia to the Caribbean. In particular its officer corps was its pride. It was drawn from all classes of society, promoted on merit in a system that prized intellect.

It was altogether impressive, this army, and yet less than a decade later during five weeks in May 1940 this army was comprehensively defeated. So total was the defeat that it was embarrassing. The defeat was as much psychological as material. French troops fought with each other in the rush to surrender. Units far from the front abandoned their arms never to touch them again because of rumours of a truce before the first radio broadcast of a ceasefire. Officers, it was said, surrendered as quickly as possible so as not to miss lunch. Censors tried but failed to suppress pictures of lone Germans herding thousands of apparently willing French prisoners along. This moral collapse turned the army into a mob by the thousands. When the German burst from the impassable Ardenne forrest, the French army fell to backbiting and backstabbing at all ranks. For their part staff officers in Paris denied responsibility and knowledge of anything and everything in some squalid episodes.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

Yet apart from some volcanic fighting in Belgium and around the Pas de Calais (Dunkirk and Ostend), the defeat resulted in relatively few French casualties, making it all the more surprising, and all the more embarrassing. In fact, French Army emerged from the defeat largely intact, though its members were divided, dazed, confused, isolated, dispirited, and exhausted. There is plenty of newsreel footage on You Tube. Have look.

Perhaps the analogy is to victims of a mighty car pile-up on an expressway.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

Blind-sided, a gigantic wallop with noise and shrapnel, and than another and another as the pile up continued. Much noise and confusion but few killed or injured. Yet all are dazed and confused.

This book is a study of how one set of the victims of that crash, the officers of the French army, responded to the catastrophe. It is a subject that takes study, because the recriminations at the time and since have been a blizzard without end, as blame as been laid this way and that, often with no other evidence than the unshakeable conviction of prejudice. In fact, it is perhaps the kind of study best done by an outsider who is disinterested in the matter. This book is based on archival material, publications of the day, interviews with participants, and, inevitably, the river of memoirs protagonists wrote to justify themselves. It is impressive to see how much microfilm of contemporary records and reports in German and French the author worked through to find the confirmation or disconfirmation of assertions that in other books are taken as read. Through this minefield Paxton picks his way with care and sound judgement.

What prompted my interest in this study was the realisation, born of reading about this period, that the chain of command in the French army survived the triple debacle of June 1940 and remained in place for the use of the Vichy regime both France and in the colonies, triple in the defeat, the surrender, and the humiliating peace.

Remember, that this army was deployed around the world in French colonies, territories, protectorates, enclaves, embassies, and missions – most particularly in Africa and the Middle East but also in the Caribbean, India, Latin America, and Oceana, including New Caledonia, today a one hour flight from Brisbane.

As discredited as defeated France was, the colonies held fast to it in this dark hour despite the clarion call from London on 18 June, when Charles de Gaulle made his first radio broadcast in the name of France Libre. Likewise, the officer corps in France also obeyed orders to return to barracks or comply meekly with capture and imprisonment. As German archives show, they were themselves surprised at the speed and scope of the capitulation and unprepared for it.

Even as two million French prisoners of war were being entrained to Germany, the remainder of the French army began to demobilise itself. While de Gaulle shined a light, in the first months few officers followed it. This is all the more remarkable considering the residual anti-German sentiment throughout France and most particularly in the army after the bloodbaths of World War I, which had led to the development the formidable army described at the outset.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

Paxton’s focus is not on the defeat but the aftermath, though he does set the scene by showing how in the years after 1931 the strength of the army dissipated. There were disputes within the army over strategy and tactics that took the form of bureaucratic backstabbing and career blockage to new extremes. Charles de Gaulle was himself one of the victims of this battle.

Though French tanks and fighter planes were technically superior to their German, Italian, and English counterparts in 1939, the doctrines that dictated their use did not exploit the capacities they had: One example, Renault heavy tanks were technical leaders, and those the Germans captured were later used to good effect on the Russian front in the following years. But French army doctrine spread them very thinly through infantry regiments as mobile block houses for static defence. They were not grouped to give weight and supporting fire power in attack. The Germans, at the time, had lesser and fewer tanks but made far more effective use of them. The same could be said for aircraft. It is also true that often the French forces outnumbered the attacking Germans, but the tactics of the Germans with tanks and aircraft overcame the numerical advantage the French had. The French also enjoyed the advantage of shorter and interior lines of communication but again German tactics cut these by attacking roads and bridges from the air. The French airforce doctrine conserved assets and did not attack German ground targets.

Even more corrosive were social attitudes of those born to the army, and their scorn for parvenus, including Jews that had entered the army during the Third Republic, especially under the Popular Front government. It went beyond the usual snobbery or cliques one must expect and included systematic efforts to degrade, discourage, and drive such undesirables out of the army. There were many little Dreyfuses victimised in a hundred small ways for the lack of a ‘de’ in the name or the presence of ‘berg’. Contrary to the post-war legends there was little liberty, equality, or fraternity in the French army by 1939.

After 1931 successive governments cut defence spending, as did General Phillipe Pétain, when he was minister of defence, and cut it again, and again as the Great Depression spread. As the ordeal of World War I receded from memory, an historic anti-militarism in French society, a child of the French Revolution when the army was the instrument of royal oppression (and it was again with the Napoleons and restored monarchs), re-asserted itself. Parliamentarians not only cut military budgets but they boasted and bragged about it, including one Pierre Laval. In the name of liberty, conscription was qualified by twenty pages of exemptions and exceptions, while the overall length of service was progressively shortened. A standing, professional army was perceived to be a greater threat to society than a foreign enemy by many ideologues who came to prominence in the Popular Front era of the Third Republic. It is also true that the Communist Party of France, following explicit orders from Moscow, disrupted French defence industries by strikes and sabotage and sheltered those fleeing conscription.

Though French generals said they were ready for war in 1939, despite later denials, the record is clear. It is equally clear that when the German offensive struck they were among the first to show the white flag. To review the last days of the Reynaud government as it fled from Paris, is to conclude that the generals gave up the fight before the politicians did. Prime Minister Reynaud himself was prepared to take the Government into exile and continue the war, as the Dutch, Norwegians, and Danes had done, but the generals, including Pétain advised him to surrender not just the army but the government itself. Reynaud could not bring himself to do that but he bowed to the majority of his cabinet and deferred to Pétain to seek terms of an armistice. Instead Pétain capitulated, precipitating generations of debate about the legitimacy of his initial government.

Later, of course, the generals blamed the politicians, but that is hard to credit. Start with the commander in chief of the field army, Maurice Gamelin, who set up his headquarters in splendid isolation from the front lines in a place chosen more for the wines in its cellar than for its communication or access to the armies he commanded. Read this sentence slowly: After nine (9) months of war, he had in his headquarters no telephone in May 1940.

Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gamelin

He sent and received messages by car and motorbike along country lanes but few roads ran to the border where the army was emplaced. He later explained his inaction in the crisis by saying that he did not know what was happening. Hmm. If communication with Gamelin was slow when nothing was happening, once the front broke he was a hard man to find. (Radio was too easily intercepted for use and unreliable in the heavily forested area and jammed by Germans.)

I referred to doctrines before. Here is another example. The French General Staff had slowly and painfully negotiated an agreement with Belgium before the war to form a line of defence on the Dyle River in Belgium. This Dyle Plan allowed three (3) weeks, 21 days, for the French Army to take its positions along the River Dyle. Care to guess how long it took Germans to breach that line? Three (3) days. Once that happened the French Army had no plan of operations. They had thought of everything except a Plan B. (By the way the British Expeditionary Force was part of this plan and was thus left without a mission.)

Overarching themes:

Officers from general to lieutenants denied the defeat by blaming politicians, British perfidy, spies, lazy conscripts, unpatriotic civilians….women who smoked, protestants, secular education. The list went on. Only the army was blameless for its defeat.

Military contempt for parliamentarians and the Army’s early effort to dominate the Vichy government. Civilian control was only established in April 1942. Apart from Maréchal Pétain himself the Vichy government was dominated in its first crucial months by General Maxime Weygand and then later for longer periods by his navy rival Admiral François Darlan.

Backstabbing, cliques, career opportunism were rife in the very hard circumstance of the armistice army that the conquering Germans permitted. This personal struggle is most well documented at the most senior levels of the army but it was not confined to the top.

Vichy played off Germany against Britain and vice versa by trying to be neutral, not so much in Vichy France itself, but in the colonies, especially those of strategic import like Dakar, Damascus, Djibouti, Diego Surez, Noumea, Oran, and Bizerte. To keep the Germans out of the colonies the Vichy regime defended them from British incursions. To keep the British from occupying a colony there was the spectre of a German response.

There was an effort to use the National Revolution of Vichy to enhance the status of the army after its humiliation. The new curriculum emphasised patriotism and physical fitness and left little time for science. Girls were encouraged to leave school at puberty.

The benign Pétain.

The benign Pétain.

The fate of two million French prisoners of war in Germany preoccupied some officers to the exclusion of everything else and was ignored by many others. These prisoners included all ranks including generals like Giraud, Juin, and others.

Inter-service rivalries that pitted the influence of the army against that of navy, and the navy won very often because it had all those lovely ships which the British wanted and the Germans did not want to Brits to get until November 1942. The army was discredited by its collapse.

The near thoughtless compliance with the purge of Jews from the army, navy, and air force. Likewise the German efforts to identify and seize Germans in the French Foreign Legion is a sorry story of compliance.

Most officers obeyed Vichy because the regime was congenial, not out of duress or desperation. Indeed those officers forcibly retired to reduce the size of the Army clamoured for re-admission.

Vichy officials reluctantly agreed to many German demands but moved slowly to comply. It might take six months to get agreement from them, only to find it was another nine months before they took the first steps. There was a lot of this kind of passive resistance. It is not easy to trace its origin. At times both Pétain and Laval expressed anger at the slow movement of their government, but at other time this pace suited their efforts to keep Germany at the negotiating table.

The Vichy regime presented itself to France and to the world as the sovereign government (of what was left) of France. See, for example, the newsreels at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU61J_xXBAE

(Cut and paste the address into a browser.)

The army’s chain of command held despite the colossal shocks of May and June 1940. By and large the French army from generals to lieutenants accepted Pétain as the government of France and obeyed his orders. But it is important to realise why that chain held despite the unprecedented jerks on it. (It might have been a different story without Pétain. A government with only Pierre Laval at the top, well that certainly would have been less compelling to most officers.)

Officers had responsibilities; they were not free agents. As long as those responsibilities remained and made sense, they stayed at their stations. Paxton makes this point by analysing the officers who joined de Gaulle’s France Libre. They numbered several hundred and then thousands and invariably they were officers who did not have command of men who were dependent on them.

De Gaulle himself is an example. He had been relieved of his field command in May and appointed an under-secretary for war in the Reynaud cabinet, and then sent back and forth to London several times to gouge greater effort from Britain.

The officers who first joined de Gaulle fell into these categories: retired, on unattached duties (ill or convalescing), attachés at embassies around the world (particularly Latin America), staff officers who did not command subordinates, on special assignments (e.g., as couriers, liaison, or missions abroad). These officers were free(r) agents than those with dependents, i.e., subordinates. They came from metropolitan France but also from the colonial forces. Of course they may have had families to think about, too.

While nearly all officers at French embassies in the the Americas saluted de Gaulle’s flag, not every retired or convalescing officer did. The second criterion that Paxton suggests was decisive is access. Retired or unattached officers who had only to travel a short distance to join de Gaulle, were more likely to do so. Many officers on special assignments were already embedded with British forces as liaison or couriers along with scores of others in the United States and Canada on a variety of missions. Some colonial officers had only to walk across the street to a British consulate to get passage to London. But retired or convalescent officers in Lyons or Metz had no such access and so joining de Gaulle may well have never crossed their minds. Later the fear of reprisals against one’s family in France held some officers in check. Others adopted noms de guerre to avoid such reprisals.

In time as the Vichy regime lost creditability. The unopposed Japanese seizure of Indochina shocked officers far and wide but most of all in Indochina, from which some intrepid souls found a way to abscond and travel, slowly, to England. German setbacks like the stalemate at Stalingrad encouraged others to abandon Vichy neutrality for the opportunity to return to the war effort, e.g., those garrisons in India (a surprising large number). While some officers were staunch themselves they turned a blind eye to the departure of junior officers, forging roll calls to fool German supervisors. Yes, there were German supervisors throughout the French colonial Armistice Army, as well as the Armistice Army in Vichy territory.

Officers in the Armistice Army in Vichy also acted in secret. Rather than turn over all weapons and ammunition to the Germans, they hid much against the future. One trove, scattered in numerous caves, mines, commercial wine cellars, abandoned barns consisted of thirty-nine (39) tanks! The tanks had been disassembled and crated, marked as agricultural material and salted away.

When American troops landed in Morocco and Algeria in November 1942, the veil fell. The Vichy chain of command was by then muddled. Mistrust, suspicion, fear of reprisals from either Germans or Gaullists, residual anti-German feeling, loyalty to Pétain, inter-service rivalries between the navy and the army, tests of will between civilian control and military, all had grown over time and reached new heights; this brew bubbled, collided, mixed, leaked when reality of an Allied invasion occurred.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

Contradictory orders were issued one after another by a single commander as information came in or was discredited. Conflicting orders came from civilian and military authorities, who then disputed each other’s right to give orders. Generals disputed the authority of other generals to give orders in the crisis. Messages from Vichy said one thing and the local representative of Vichy said another.

Because communication with Vichy was disrupted, the chain of command was altered, but not everyone got the message about the change. Some commanders got orders from generals they had never heard of. Confusion was the result and that led often to inertia and paralysis. Though the reaction of soldiers when attacked is to reply in kind, there was no decisive leadership and the will to resist dissipated within hours. The soup of conflicting orders, contradictory orders, the unabated undermining of rivals confused the matter all the more.

One example is a captain with a company on the beaches at Casablanca received orders from a his colonel to greet the arriving Americans as allies, and almost simultaneously orders from his major to fire on the landing parties. Faced with this contradiction, the captain took his men back to the barracks. The colonel and major were each passing on orders they had received.

In this mire, the castle was Algiers where the headquarters of the French colonial forces in North Africa was located. The conflict and contradictions were played out there with full force. In addition the American sponsored alternative to de Gaulle, Henri Giraud arrived with his immense prestige as a soldier and his childish incomprehension of the political situation, along with the American commander General Mark Clark whose campaign had already fallen behind schedule. In addition, François Darlan, Vichy Minister of Defence and commander in chief of the French navy was in Algiers on private visit to his ill son. The clash of these egos was seismic. The French would not agree among themselves, still less with Clark, but he had the bayonets.

At stake in this opera in Algiers was nearby Tunisia. It was the frontier between Vichy North Africa (and now the Allies) and Rommel’s Afrika Corps in Libya. The Germans wanted to use Bizerte as a port to supply Rommel. Vichy neutrality forbade that. When it became clear that the Allies had taken over in Algiers, and when de Gaulle arrived there and ended the fruitless negotiations with Vichy officials, the Germans stopped asking and started taking. In response the French troops in Tunisia turned on the Germans. As soon as this switch was reported by the Germans to Vichy, Pétain relieved the Tunisian commander, General Alphonse Juin, who ignored the order on the assumption that Pétain’s hand was forced by Germans. The chain of command snapped at long last.

Now the Armistice gloves were off from Morocco to Tunisia and Djibouti, and French officers along with their commands in these stations joined the Allies as speedily as possible. Within a few months every French colony was aligned with France Libre. Thereafter, General Juin’s 100,000+ man First French Army led the way in the Allies’ Italian campaign. At the bitter end, Free France had 250,000 soldiers in the field in Europe.

The necessities of war brought Great Britain and Vichy into conflict to be sure. While Hitler had promised not to seize the French fleet, he was not a man famous for keeping promises. While French admirals swore not to let their ships go, would they be able to resist at the moment of truth or would they, like so many others, be overwhelmed by the Nazis?

Noteworthy, but not mentioned is that the Armistice Army was never used to enforce order in any sense. This army did not round up Jews. It did not kick in doors to arrest trade unionist. Its parades were not designed or intended to intimidate onlookers, in contrast to German parades in France. Rather these parades were intended to boast morale in the ranks and in the viewers.

I do wish the author had included some kind of chronology of major events with a comment on the fallout of each as I did above.

I do wish the author had included more numerical information, i.e., data about the military formations discussed. Numbers are mentioned at times, but a table or graph would be more effective.

I do wish the author had more systematically distinguished the metropolitan Armistice army from the colonial Armistice army, and then offered some general account, complete with tables, of their size and distribution.

Only a few sentence end with conjunctions in this book, however. This regrettable tendency is much in evidence in another Paxton’s books.

‘Pierre Laval and the Eclipse of France, 1931-1945: A Political biography’ (1968) by Geoffrey Warner

Laval was the dark prince of the Vichy Regime (1940-1944).

Pierre Laval in 1931

Formally, he was prime minister while the venerable and elderly General Phillipe Pétain was president. These two hated each other and spent a good deal of effort in undermining one another. Although Pétain was willing to collaborate with the Germans and re-make France into an agricultural nation bound to family and church and reject the Third Republic and end all that liberty, equality, and fraternity rhetoric in favour of work, family, and country, he did draw lines against the Germans. Not so Laval who gave in to German demands at every turn, and at times offered more than the German demanded. He said that he did it to secure the good will of the occupier. There was never any evidence that good will resulted. When the Germans demanded slave labor, disarming the fleet, handing over Jews, Laval complied. Pétain did not.

Laval had entered the national assembly as a Socialist, having had a career as a labor lawyer. There he formed a boundless ambition, and a belief in himself that became delusional. In pursuit of that ambition he moved across the political spectrum to the centre and then the right. In the Third Republic in the 1930s he was a foreign minister, interior minister, and prime minister at one time or another.

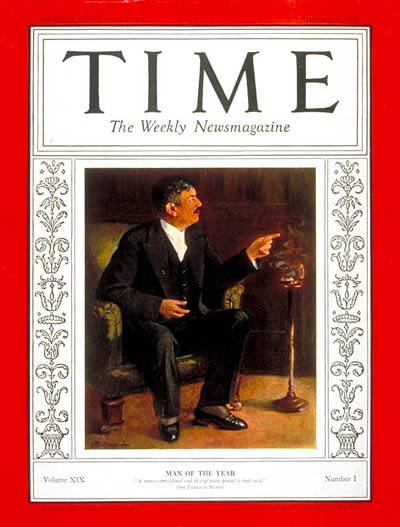

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

In each case he was convinced that he alone could save France from external enemies (Germany) and internal ones (Communists).

In this biography he seems not to have been a reflective or introspective person. Self-doubts, he had none.

I said ‘delusional’ above. To explain, while prime minister he hoped to befriend Mussolini’s Italy and use it to restrain and buffer Hitler. At the time he started on this policy it had some promise. But to everyone but Laval it soon became apparent (1) that he had no influence with anyone in Italy and (2) that Italy followed and did not lead Germany.

No evidence convinced him to change his course. One rebuff after another from Rome, was dismissed as a bargaining ploy, an effort to conceal his influence from Hitler. In the effort to stop Laval’s endless messages to Rome, the Italian foreign minister wrote a letter, couched in very undiplomatic terms, to tell him to stop and sent it to the French foreign minister of the day who read it in parliament in an effort to silence and embarrass Laval. It did not slow him down a beat.

Later he developed a similar fixation on his capacity to influence Hitler, and repeated rebuffs did not faze him. He had a number of interviews with Hitler, and got virtually nothing from them, but that only led him to try harder to get another meeting where he would surely score a great coup.

One of many meetings

One of many meetings

How others saw him

How others saw him

Nor were his delusions limited to foreign relations. His start as a socialist gave him the abiding belief that he (alone) could unite the social divisions of France. Each failure to do so, he took as a sign that he was succeeding little by little.

One can only admire his tenacity and optimism while deploring his grasp of facts.

Maréchel Pétain was 84 when the Vichy government took form. While the Germans and the French were glad to have such a respected figure associated with the papier-mâché regime, they also considered that he might die at any moment. Anticipation of what might happen if he died, set off one palace intrigue after another as members of the Vichy government manoeuvred to have themselves named as his inheritor. Laval was the most conspicuous schemer but he was certainly not the only one.

By December 1940 Laval had irritated most other members of the six-month old government since its inception in July of that year. He was always a fast worker. In order to secure German good will he had cut across the domains of other ministers and given away French assets for a hand shake, and sometimes not even that. Accordingly, six of the eight other minister convinced Pétain to dismiss him. Pétain did not take much convincing.

It was done with a combination of subtlety and force. It was a ritual of Third Republic governments for ministers to sign a collective letter of resignation which the head of state (Pétain in this case) could use to drop an unpopular minister and placate public option or the parliamentary parties. At a routine 8 pm cabinet meeting one such letter went around the table and each minister signed it. The unspoken assumption, at least in Laval’s mind, was that it would be used to drop a junior minister who was ill and not at the meeting. As per the ritual, when the letter got to Pétain there was a short break and he retired to another room while the others drank coffee and smoked. He came back ten minutes later and said the ‘resignation of M. Laval has been accepted.’ The explosion went off!

Laval, completely taken by surprise, shouted, thumped the table, and nearly cried. To Pétain who had stood down generals under fire this reaction was most unseemly. Laval was bundled out of the room by other ministers and taken into custody by the Praetorian Guard (Pétain’s body guards) and put under house arrest some miles away. Although Pétain had told the Germans a few hours before he was making a change of government, they, too, were surprised and demanded Laval’s immediate re-instatement. Pétain refused. After 72 hours of pistol waving, angry telegrams from Berlin, a new prime minister (who was acceptable to Berlin) was named, and the Germans took Laval to Paris for the next 16 months.

Note that it was in Paris that the real extremists congregated and not in Vichy. The French fascists, the anti-semites, the New Europeanists (code for the German Europe), published newspapers, pamphlets, and books in Paris damning the Vichy government for its sloth, weakness, and lack of enthusiasm for the opportunity to cleanse France. They produced anti-semitic films and curated anti-semitic exhibitions. Applied their creative powers to anti-British propaganda which convinced themselves, if no one else, that Great Britain was the real enemy. They held rallies and attacked all manner of people in the street to show how tough they were. A few (very few) who really believed what they said volunteered for service on the Russian front. Laval was never quite comfortable with these zealots; he was — I think — an opportunist in service of his ambition and not an ideologue.

During this interregnum the Germans kept Laval on tap in Paris as a threat to the Vichy regime. If it did not comply with German requests, the Germans retained the option of creating a new French government in Paris with Laval at the head. Remember that by now Pétain was 86 and he might die at any moment. If he did can anyone doubt, they reasoned in Vichy, that the Germans would crown Laval? For his part Laval toadied, conspired, lobbied, and generally tried to ingratiate himself with German authorities.

Absent Laval, the scheming and musical chairs in the Vichy regime continued. Prime Ministers came and went, each trying to get Pétain to pass the mantle onto him. Ministers and ministries changed monthly or so it seemed. Until November 1942 Vichy did exercise administrative responsibilities of many kinds but once the Allies landed in North Africa that ended. Yet the Germans continued the mirage of Vichy as a means of stability. At the insistence of the Germans Laval returned to Vichy and to government after 16 months of his Paris exile and exacted his revenge on everyone, though Pétain himself and his immediate entourage was untouchable, not so others who were soon deprived of position, income, accommodation, and even papers. The Germans perceived Laval as the most pro-German of the Vichy figures and they also wanted at least the veneer of continuity in the Vichy regime.

Laval, that master of self-delusion, continued to suppose the Germans would win the war and said so often. That had been plausible in August 1940 but it no longer was in August 1944. No evidence could ever dent the Maginot line of his delusions. Throughout 1943 Laval conceded nearly every German demand. Indeed, he only declined in cases where he did not have the capacity to deliver.

Oddly enough as the Vichy regime withered and shrunk in early 1944 there was a clamour from the Parisienne ultras to join the government, and Laval finally agreed, over Pétain’s objections. As the ship was sinking, more rats got on it.

In August 1944 with American, British, and Free French armies a few miles from Paris, the Germans, perhaps out of the same strange loyalty that led to the German rescue of Benito Mussolini, moved Pétain and Laval and few others to a castle on the Danube. Laval had fled to Spain but the Spanish surrendered him to the French provisional government which tried and executed him in short order. Initially Laval seemed to think he was going home to a hero’s welcome.

At this trial he lied as freely, as he had done throughout his career, and when presented the evidence of a lie, he shrugged and went on.

There is no doubt that in the end Laval believed he had done France a great service by buffering the Germans. Like Socrates, he nearly suggested that he be rewarded rather than condemned. The author refutes this claim with some comparisons to other occupied countries like the Netherlands and Belgium who governments went into exile.

His trial was no model of justice, but the author contends that there was and is no doubt that Laval was guilty of treason, however defined, but certainly within the meaning of the relevant French law. A lot more guilty than, say, Alfred Dreyfus or Léon Blum who had been tried on this charge in trials that were not models of justice either. Nor can one deny the conclusion that Laval was also a scapegoat for a lot of other people who trucked with the Nazis.

The book is definitive. It is based on primary sources from French and German archives, both civilian and military, with other material from the United States, which (too) long maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy regime. It is measured and the prose clear, letting the story speak for itself and letting the reader draw conclusions.

Simone de Beauvoir, who is not mentioned in the book, covered Laval’s trial for a newspaper, and remarked that as much as she hated him, and hate him she did, the Laval that was on trial was not, or did not seem to be, the man she hated. He was diminished, small, uncertain, cowed, not the brash, bull-headed know-it-all man, who crashed through and crushed all in his path. Some of that diminution is physical. Laval’s table had always been sumptuous in Vichy, even when the rest of France starved, but after August 1944 he lived on German army rations and then prison food. He lost weight and colour from his complexion, the hair greyed. His one suit of clothes wore through. Then there is the fact of being on trial for his life…the round shoulders and bowed head. His was no longer the whip-hand. Her essay is reprinted in her ‘Ethics of Ambiguity’ (1962).

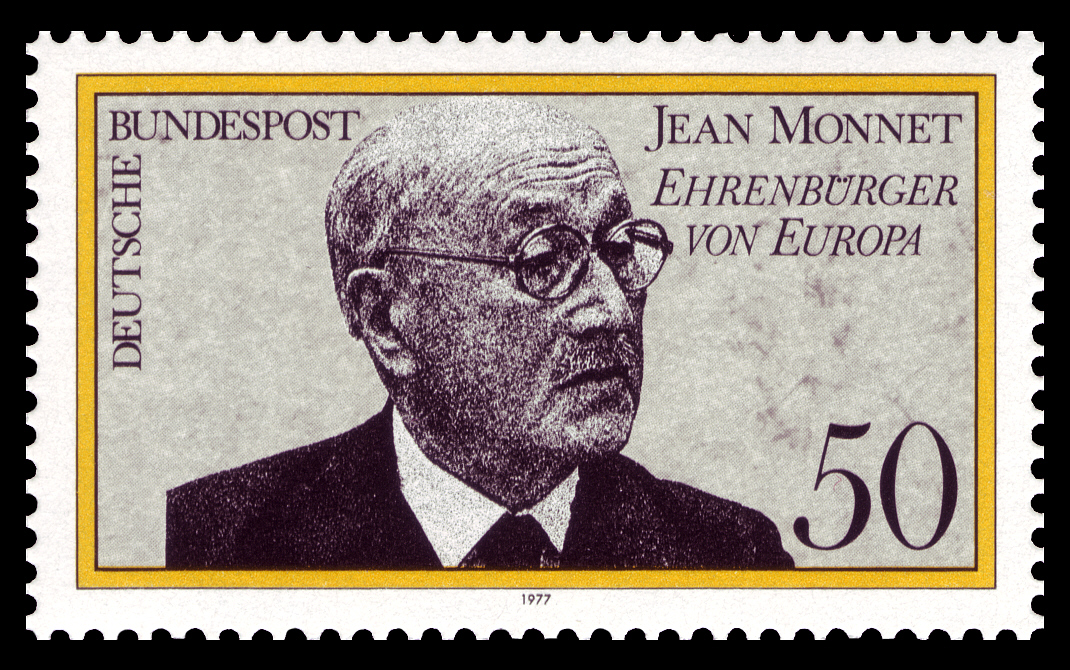

‘Jean Monnet: Unconventional Statesman’ (2011) by Sherrill Brown WELLS

‘Jean?’ who you ask. Jean Monnet (1888-1979). He ought to be called ‘The First European,’ since he is widely regarded as the mid-wife of the European Community. Quite an achievement for someone who never held an elected office and who was never a civil servant. Yet by wit, tenacity, wisdom, patience, a vision, an appetite for data and facts, a network of friends and acquaintances all over the world, he kept moving toward a European union, and he got a lot of other people to move in that direction, too, including Charles de Gaulle.

In 1938 the French Prime Minister sent him on a special diplomatic mission to the Washington D.C. In 1940 Churchill gave him a British passport and sent him on a special diplomatic mission. In 1943 Roosevelt entrusted him to be his representative in Algiers.

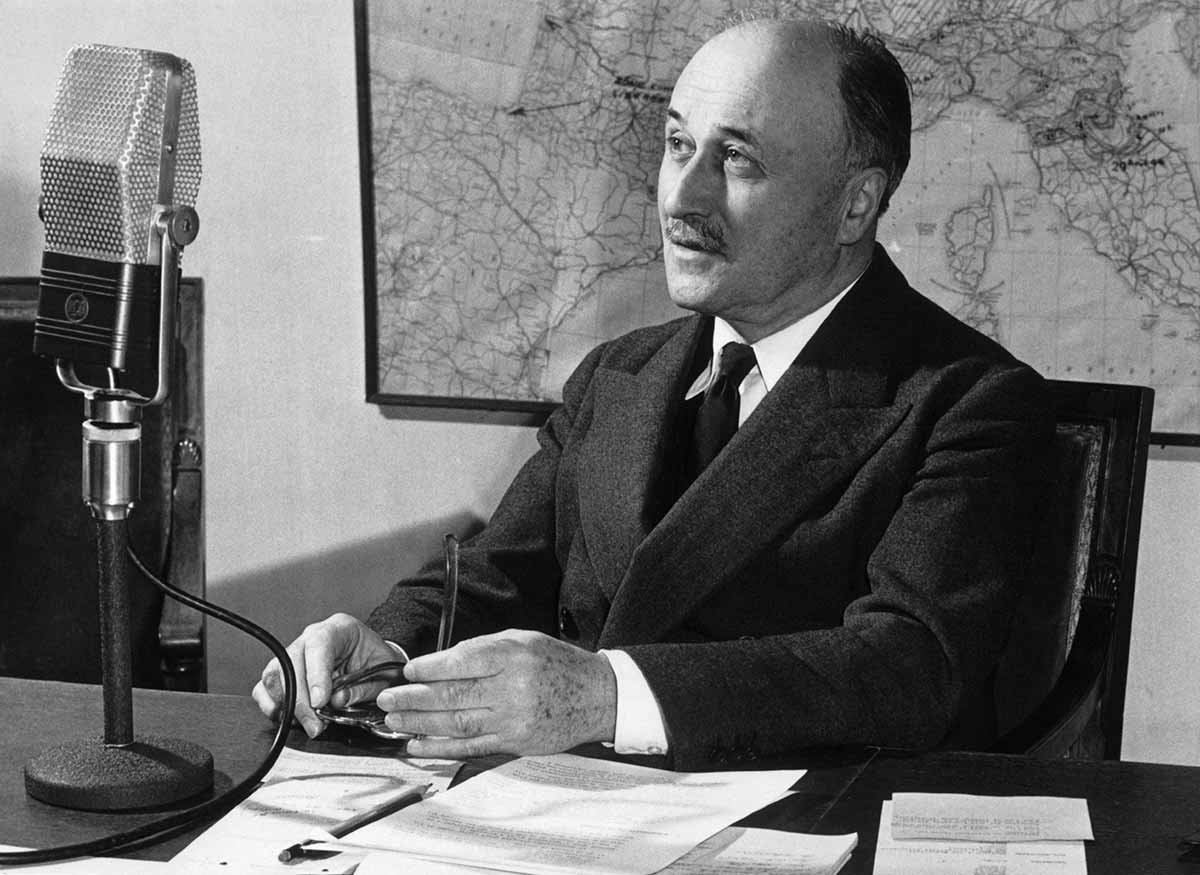

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Internationalist indeed. This was just the beginning.

In Monnet’s mind European union was the means to the bring of enduring peace to Europe. He was born into a wine family in the Cognac and began working for the family company at 16. At that age he learned enough German to sell barrels of brandy to German buyers. Later as his father innovated and expanded the business, he sent young Jean to London to learn English while selling brandy. There he found his best single customer to be the Hudson’s Bay Company of Canada which bought in volume for national distribution. In time the Bay hired him, with his father’s encouragement, and he spent time in Canada, and from there the United States.

Asthma kept him out of the army in World War I, but, inspired by his experience with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he proposed to the French government that it join with Britain in a consortium to purchase not just war materiel but everything else, too, including the shipping to transport it, and the bank loans to pay for it all. An Inter-Allied Committee evolved out of this suggestion and Monnet was its executive assistant, and in no time at all he ran it in everything but name. There were many conflicts on this committee and Monnet was the one who never gave up, who stroked egos, who broke the conflicts down into a small pieces to find common ground, who developed the spreadsheets to demonstrate the priorities…. This committee was successful beyond anyone’s expectations. By the way, it was a small committee of four (USA, England, France, and Italy) and that was another enduring lesson. Keep executive committees small.

Toward the end of the war he left that committee and worked for Herbert Hoover in war relief for Belgium and France in that Herculean effort where twenty hour days were the norm.

At the end of World War I he went to work at the League of Nations, serving there for three years as an international public servant. He passes through Frank Moorhouse’s superb novel ‘Grand Days’ set in the League.

Lured by the business opportunities offered by friends in the United States he moved there and made millions of dollars only to lose it all, as did so many others, in the Great Depression. He went from multi-millionaire to pauper in a few weeks. His passage back to France was paid by friends, including John Foster Dulles.

Never one to sit idle, back in France he received an offer from Chiang Kai-shek’s government in

China to set up and import-export bank in Shanghai. One of his League of Nations colleagues had recommended him for the job. He took it and succeeded, where several others had already failed. Later a dynastic power play in Madam Chiang’s family pushed his patron out of the bank and Monnet with him. His greatest achievement in this venture had been to convince the Chiang government that it had to re-pay all outstanding debts before trying to borrow more. This was a hard sell and it took a couple of years. He also made quite a profit from the three years he spent there.

He married an Italian woman who had left her husband. No divorce was possible in Catholic Europe. Both Monnet and his wife-to-be became Soviet citizens because divorce and re-marriage there was easy. She travelled from Switzerland to Moscow and he from Shanghai and there she divorced her husband and married Monnet. Reds! How did he live that down in the Cold War? This book sheds no light on that.

When he returned to Europe Monnet hatched a plan for France to buy airplanes from Canada. These airplanes would be assembled in Montréal from airframes and engines manufactured in the United States, in a work-around of its policy of neutrality. In the course of devising this plan Monnet had private meetings with President Roosevelt at Hyde Park.

The French capitulation occurred before those planes were delivered, 5000 in all, but Monnet on his own responsibility signed them over to Great Britain. For this act, and many later ones, the Vichy French regime charged him as a traitor. De Gaulle did the same, by the way, with military equipment intended for the French army in 1940: Gave it to Britain.

Churchill’s desperate gesture to keep France in the war in May 1940 after Dunkirk was to create a union government combining France and Great Britain as one. Churchill offered to defer to Paul Reynaud as the head of such a government. Quel beau geste! In London Monnet wrote the text for Churchill. The idea was that then Reynaud could take the government out of France to London and the French fleet and France’s considerable colonial army could be brought into the war. Reynaud could not convince his cabinet to continue the struggle and the moment passed.

Though Monnet supported de Gaulle’s effort to keep France in the war, he feared basing it in London would compromise it in the eyes of Frenchmen, which it did. He tried to convince de Gaulle to move to Algiers, and so remain on French soil. De Gaulle did not, and probably wisely. To move Free France to Algeria in 1940 or even 1941 might have meant capture by Vichy. Moreover, even if Algiers could be won over, location there would mean foregoing the material support Great Britain offered in London.

In 1943 Monnet was thinking ahead about European reconstruction. In Washington he used his business and political contacts to talk incessantly about the necessity of economic reconstruction to ensure social stability, including one lunch at the Pentagon with George Marshall. Monnet was responsible for American Lend-Lease supplies going to Free France. In fact, at the times he was the de facto American administrator of Lend-Lease going to Free France, and the de jure French manager of the supplies obtained. In this role he was a tyrant for propriety, insuring there was no hint of the graft, corruption, or profiteering that marked so many Lend-Lease operations elsewhere. This propriety made later Marshall Plan funding easier to justify.

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

The historic conflicts between France and Germany, in the industrial age, had focussed on the Saar, Ruhr, Pas de Calais, Alsace, and Lorraine because there is where the coal and steel was. In 1943 Monnet was drafting plans to internationalise these regions under joint control of three or four countries. This is the seed of the European Coal and Steel Community, which later gave birth to the European Community. Monnet’s idea was to take the means of modern war out of the hands of a single country to put them into some kind of transparent international protectorate.

He was the author of the Schumann Plan that embodied this ambition and led to ever greater French and German collaboration and European unity. It was not easy going, and it took nine complete versions to get a plan that both France and Germany accepted since it involved a diminution of sovereignty. While others gave up and quit, Monnet persevered. The European Coal and Steel Community became the first voluntary European entity since the Holy Roman Empire. I omit the League of Nations because of its origins in Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on it as the price for the Treaty of Versailles to end World War I.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

No sooner was the ink dry on the Treaty of Rome in 1957 which marked the beginning of the European Common Market, European Community, European Union of today, than Monnet began to talk about financial integration. He set up an Action Committee of private citizens, partly funded by foundation (including Ford and Rockefeller) grants, to organise seminars, radio lectures, publish discussion papers on financial integration, brief journalists which in time came to be a common currency, the Euro.

As successful as he was, Monnet had failures. Try though he might, he could not convince Roosevelt to recognise de Gaulle’s Free France as the provisional government of France in 1943.

Monnet also proposed a European army, partly motivated by the Soviet Union’s machinations at the time of the Korean War. This, too, failed. His aim was to contain German re-armament within such a pan-European army.

Another failure was Euratom which he proposed to make nuclear research European and so not put to military use by a single nation. France itself would not agree to this limitation, though the initiative is in the genealogy of CERN in Geneva today.

How did Monnet do all of this? Most of all he was a salesman. He loved big ideas and no idea was too big to interest him. He did not think of reasons why a big idea was impossible. As he emerges in this book, he is not reflective, nor introspective, and certainly not given to self-doubts. The harder the sell the more energised he seems to have been. He was not a writer either. The many policy proposals and discussion papers were terse, and detailed in dot points, graphs, tables, maps, and charts. The text would be filled out later by others. His preferred method of exposition was discussion and he was a master of that whether in a seminar, at the podium, dinner table, or a seat on a train or plane. Every occasion was used to develop, test, and advance the big ideas.

How did he live? Often he was sustained by the grace and favour of friends and admirers. He had no fortune and long ago he had signed over his share of the family business to his brothers. The money he made in China was considerable but moving in the elite circles he did meant the best restaurants, the best hotels, first class passage on ships and planes. He exhausted that money soon enough. His service on one special mission after another, yielded living allowances and nothing more. When at 70 he slowed down, to live on …. a pension derived from his three years at the European Coal and Steel Commission and that is all. He agreed to write memoirs in return for a hefty advance which supported his last years.

His name is everywhere in Europe. On postage stamps, commerative medals, universities, think tanks, government fellowships, busts and plaques in foyers of EU buildings in Geneva, Brussels, and Strasbourg, and the like, and yet he remains largely unknown, ever the stage manager in the back while the stars tread the boards before the audience of history. Indeed his name can also be found in Australian universities and yet few could say more than a sentence about him.

Monnet cognac remains in the market though no member of the family is now associated with it.

The book is comprehensive and thorough with admirable documentation. It is far more interesting than the first biography of Monnet I tried to read. Perhaps because Monnet was not a leader and did not hold an office, there seems to be little drama or momentum in the book. To confess, as fascinating as the story is, I found it a test of will to finish reading it.