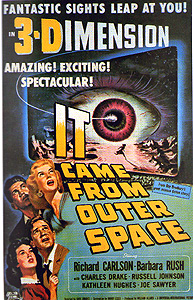

One of the first and best flying saucer movies, but without a flying saucer in sight. Richard Carlson and Barbara Rush star with a very able supporting cast. Jack Arnold keeps the pace moving.

It was made in 3D when that was the fashion for creature features.

It was made in 3D when that was the fashion for creature features.

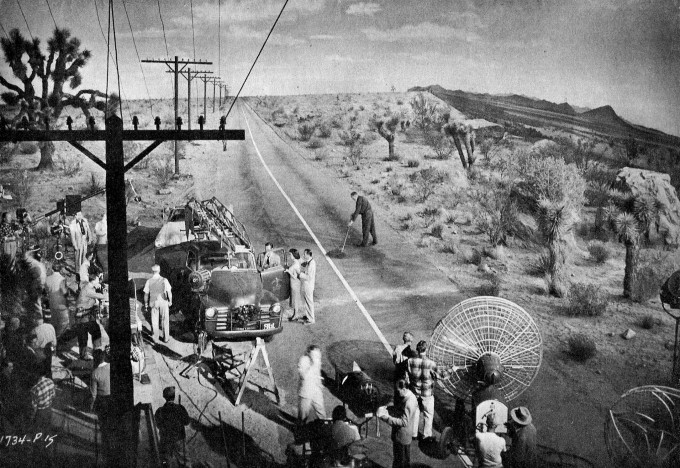

The film is dominated not by the leads nor the alien(s) but by the Sonora Desert around Sand Rock, Arizona, replicated in a studio. The screen play and the director make full use of it.

The desert created on a soundstage.

The desert created on a soundstage.

There is the starry sky of desert at night. In the early morning comes whispering wind in the telephone wires along an empty highway. In the Death Valley heat of the day prevails an eerie silence of a sun bleached desert. The long shadows of dusk make Joshua Trees seem alive. It is itself an alien environment that serves as a surrogate for the alien(s). (In the same way the Arctic does in ‘The Thing from Another World’ [1951].)

Richard is an amateur astronomer and with his best girl, Barbara, see a gigantic nocturnal meteor fall nearby and investigate. Whoa! He clambers down into sizzling hole and sees a craft. but before Babs can have a look rocks fall on top of it and conceal it. Was the fall of rock an accident or a contrivance? He does not know.

Will she, the science school teacher, take his word for it, or not?

This is the first of several instances where Richard has to convince another. He does so by persistent reason, evidence, and argument, and he succeeds first with Babs, and later with Sheriff Drake. How rare it was in a Sy Fy thriller to see sceptics brought around by argument and evidence. What it usually takes to change their minds is a god-awful slavering alien as in ‘Killer Klowns from the GOP.’ Not so here. Personal credibility, circumstantial evidence, the accumulation of oddities, and more reach the tipping point.

Richard Carlson is perfectly cast and plays the reserved and introspective intellectual right down to the elbow patches on his Harris tweed sports coat. Later he was busy leading three lives.

At the climax Barbara Rush, blank and expressionless in an inexplicable posh evening gown fit for a royal reception and a flowing scarf, is ethereal on the ridge. She says nothing but nothing is sometimes a lot, Cordelia.

Dressed for dinner with the aliens.

Dressed for dinner with the aliens.

In this regalia she and Richard have a showdown that still surprised me when I watched it again recently on Daily Motion. This is a teaser, more below.

Earlier the telephone repairmen, Joe Sawyer and Russell Johnson, get some of the best lines and moments on camera. Again that is a rarity in the genre for supporting actors to get this much screen time and importance. These two working stiffs respect the desert, and even see poetry in it.

The stiffs at work.

The stiffs at work.

Sawyer, the older man, does a memorable turn as a zombie, his face so cold and dead… [Words fall me.]

Zombied.

Zombied.

Russell is good too but not quite as otherworldly as Joe. Yes, this Russell was later the professor with Gilligan. [Those poor people!] Sawyer served his time later in ‘Rin Tin Tin.’

The alien(s) get up to some mischief and Richard Carlson is on the case and in time slowly convinces others to cooperate, though of course the carrion of the press mock him at every turn. He discovers that an alien ship has crashed and is being repaired in order to leave. To make those repairs it has zombies Joe and Russell and others to work on the ship. Once the repairs are complete, they will leave. Promise. Promise. Promise. Is this Yalta again? Will the Reds leave Eastern Europe after things are righted? Ha! The Sherrif knows his Paul Harvey and does not believe a word of such promises.

Will egghead Richard fall for that line? Is he a fellow traveller? Or will he be a real man and give in to xenophobic hysteria and blast the damn thing!

This is the Cold War moment. Will Richard go all weak and liberal and let the alien(s) complete the business, or will he get all macho and call out the nuclear posse? Which will it be? A shoot out or a truce? Or something in between.

Again a rarity in the genre at the time even to pose such a question, let alone the way it works out.

Spoiler coming. Richard convinces the posse that an accommodation with the alien Reds is best for one and all, and it is. Once the ship has a new muffler, off it goes, first releasing all the zombies.

When Richard follows Babs off the ridge he is in for several surprises. First she tries to lure him to his death. Some squeeze she is. When that fails, she fires her phaser (where did she stash that phaser in that form fitting gown, the fraternity brothers asked) at him and, zig-zag, it cuts into the rock behind him, while he fumbles for the gun in his pocket; he has fumbled for it before, and he….yes, he shoots her dead. Huh! Because he realises she has been zombied, too, and this is not the real her but an avatar used by the aliens.

This is where the logic breaks down. Clunk. It seems that for the aliens to use a person’s avatar they have to take physical possession of the body. They create avatars of Joe and Russell to do the shopping and keep their real bodies on alien ice in the cave. See? They have done the same with some others and the avatars are all busy working on the space ship when Richard, fresh from killing avatar Babs rushes in on them. So far so good….

But first, why would aliens need human labor in the first place. Yes, to go into town to buy and steal copper wire, but to work on the ship? Is this a design flaw, that the aliens cannot work on their own ship but need human hands to do that? How low was that bidder.

The human avatars are working under the supervision of…. [wait for it] an avatar of Richard himself with whom he proceeds to negotiate. But, they have his avatar, having earlier cleared his closet of clothes, though no one knows why all his clothes were needed for one scene, but not his body! See? No, neither do I.

But at least two of the aliens have been killed. The avatar Joe was shot by the sheriff’s posse at a roadblock and incinerated, and Richard plugged Babs with his fumble shooter. No fuss is made over these collateral KIAs by the aliens.

The sheriff holds off when the real bodies are released in a show of good faith while Richard and himself take a tearful farewell.

Kind of surprising that HUAC did not come red-baiting after the makers of this film, as it did after so many others for so little because a headline is a headline.

Is it an alien or aliens, singular or plural? It is never quite clear. Sometimes there is a subjective camera from the alien point of view, watching the repairmen, or others, through a clouded (vaselined) lens. So simple and so effective. There was a production argument about whether to show the alien. The marketing department won that argument. It wanted a creature to feature on the posters and in the trailers. Something for the women to scream at. Though in fact that never happens in the film, it featured in the advertising. There are lies, damned lies, tweets, and advertising.

In the early 1950s enthusiasm for creature features, Sy Fy got a boost. Ray Bradbury, who later became one of the deans of Sy Fy, was hired to write story for film. He did it in five weeks and turned in a hundred page story. All the ideas are there, but it was not a screen play.

It was turned into a script by a hack who broke up the monologues into dialogues, blocked the content out into scenes, and re-arranged it into set-ups. Then the director went through it and cut much text to be replaced by camera shots, gestures, close-ups, stage directions, and tracking shots. The the producers reorganised it into a shooting schedule to economise on sets, costumes, extras, camera time, and so on. The hundred pages shrank.

In Bradbury’s story the alien is singular and never seen. What is the old adage? Leave the creature unseen and let the reader’s imagination fill it in. But that was too subtle for the creature feature market. Indeed, rubber masks and suits of the creature features were awash at the time and to be competitive in that market segment, there had to be a visual.

It rates a mediocre 6.6 on the IMDB; that puts it level with some of the excrescence of Adam Sandler.

Author: Michael W Jackson

Free public education and yet here we are.

Think about it. Free public education for more than a century and a half has brought us to this point.

The Twitter-in-Chief,

‘Top Gear,’

climate change denial,

Erich von Dänikan,

Faux News,

the NRA hegemony,

all those No voters, and

the demographic that watches Channel 7Mate.

Are these the fruits of all the time, money, effort, intelligence, good will, and energy put into free public education for 150 years? Now that is a depressing thought.

All those stalwarts who championed free public education did so in the belief that it would lead to an informed, intelligent, rational, patient, and capable citizenry and all those teachers who have laboured to realise that vision, all of that and yet….

Who is going to explain these results to the shades of Harriet Martineau and Horace Mann?

Eric Blair, we need you now more than ever. One of Blair’s biographers, Bernard Crick, says Blair was partly moved to write ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ because he feared that free public education would not prevent the society he portrayed in the novel.

‘Space Probe Taurus’ (1965) or Exteriores Spatium Nullius

A movie made for the drive-in market, written, produced, and directed by Leonard Katzmann who has a lot to explain. The IMDB score is 3.8/10. With that in mind…. Some 1960s role modelling kills any nostalgia for those days.

In the distant future year 2000 the Space Probe Taurus is launched, though the probe is called Hope One. The crew members say repeatedly that their destination is Tyrus. Watch and listen but Taurus never puts in an appearance. That slip is characteristic of the standard of this waste of celluloid.

Notice the gat in hand. Wanna shake? Ready to shoot.

Notice the gat in hand. Wanna shake? Ready to shoot.

The crew of four strap into the La-Z-Boy recliners and blast off beyond the solar system. Note: beyond the solar system. Got it? Good, on that more in a moment.

There in deep space they come upon another space ship drifting by. They hail it but no one is picking up the phone. OK, they suit up, and the suits look pretty good (credit the wardrobe department) and float over where they force the door, saying it was not locked. Ah huh, burglars aways say that. Then they enter the engine room and start checking the instruments. Whoops! An alien appears in a rubber suit to protect those delicate instruments. After some mutual staring, the rubber alien refuses the handshake the unwelcome and intruding Hope captain offers, who then promptly shoots the alien with the .45 he was packing into deep space. Bam! So much for first contact. Shake or else!

Wait! It gets worse. They decide to blow up the alien ship. Whatever for? To hide the body of their victim? No, but because gravity will pull it to Earth where it will crash and hurt someone. This from beyond the solar system, remember? Deep space, get it?

Are there any more aliens on board? Are there other alien crew out and about in their rubber suits yet to return to the ship. No one knows. No one checks. No one cares. Boom!

The Probe is called the United States Probe. Not Earth probe, but United States Probe. It fits US foreign policy, bam and boom.

There is more to come. Through no fault of their own they do land on a habitable planet, where they promptly kill the first inhabitant they meet. Consistent anyway. Thereafter they congratulate themselves on finding a habitable world. It will be habitable as soon as all the indigenous inhabitants are murdered. Think Australia. Hence the ‘nullius’ in the alternative title above.

There is no irony in any of these events. Not hint of it. The acting is leaden. The story, well, what story. The special effects are rubber. Could be I am making it sound better than it is. This’ll cork it: Roger Corman made better movies! Thought I would never say that of anything.

The crew of four includes a woman, much to the annoyance of the captain who wants chaps. Bet no one expected that! But she got the job because she is a light weight. Literally. She weighs less than a male scientist. Is this clever or what? (Or what.) The two younger crew men hit on her and she finally relents. The rejected suitor, sacrifices himself to extricate the ship from another blunder. Role modelling, indeed. THE END. Amen.

In the second to last scene we learn that the probe is a desperate effort to find a place to relocate the population of the Earth or is it the United States, for reasons not theretofore mentioned or further explained though i suspected it was the aftermath of a GOP majority. Maybe as the end neared someone thought to justify the mayhem earlier in the film. Hmm. Not likely. Probably filmed that last scene first, a common practice, and then just forgot about it. Something I have tried to do myself.

No one ever watched the last feature at a drive-in, anyway. Wisdom in that, as well as hormones.

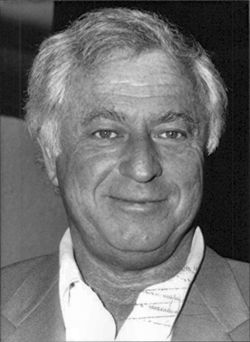

Leonard Katzmann much later.

Leonard Katzmann much later.

Thirty years later Katzmann directed more than sixty episodes of ‘Dallas.’ Atonement in that punishing duty?

‘The Atomic Man’ (1955)

It has also been released as ‘Timeslip,’ which reveals the plot. It is a low budget science fiction film.

The acting is fine and the direction is crisp in the film noir manner of the era. (It was cheaper to film in low light and so many B movies were noir primarily for this financial reason.) The story is another matter. The science is silly. The villains do their best with underwritten parts. For a thriller there is a lack of urgency.

It was a ’quota quickie’ and that explains its schizophrenia about whether it is American or British. All the cast are British except for the two leads, Gene Nelson and Faith Domergue, but all speak of dollars, not pounds. Newspaper reporter Nelson fastens onto the mystery man pulled from the river who bears an uncanny resemblance to a nuclear scientist splitting atoms at a top top secret installation down the road. Connect the dots.

The secret work is no secret to Nelson who barges in and around with insufferable audacity that only works in movies. Ditto he has no trouble getting into the hospital ward guarded by the police where the victim is lying in a stupor.

Nelson and Domergue are a good team, she being a newspaper photographer.

The team at work.

The team at work.

He is the action man and she does the thinking. Sporting a noir trench coat, she figures out the problem and takes several initiatives, unlike the female lead in many films of the era. But she is also stereotypical enough to wait in the car while Nelson does man-stuff, i.e., yelling at people. Don’t blame him, he did not write it.

More interesting than anything in the movie is the public policy of the ‘quota quickie’ in post war Great Britain. Westminster legislated that 25% of all cinema screenings be British made. This was not in the interest of stimulating the British film industry which at the time was working at full capacity. No. The purpose was to reduce the importation of American films by crowding them out of the theatres so that the earrings of imported films would not taken out of the country. Subtle, huh? There was no prohibition on American films, but a squeeze on cinema proprietors to discourage showing them.

However, because the British film industry was already at capacity, many studios subcontracted the films needed to meet that 25% quota to all comers, like the legendary Danziger brothers (who could knock of the unforgettable ‘Devil Girl from Mars’ in ten days), and to American shell companies set up in London in response to this opportunity. These American companies in turn put a few American touches in the films so that they could be shown in the States in the bottom half of a program or a drive-in triple feature. (Those were the days.) The touches might be leads like Nelson and Domergue, references to dollars, or mid-Atlantic accents from Brits.

This practice of subcontracting undermined the purpose of the policy yet complied with it and yet all the same channeled the money into American companies, actors, and writers.

Nelson started as a dancer but three years in the army in World War II ended the dancing days. In movies he played opposite Debbie Reynolds, Doris Day, and Virginia Mayo early in his career but as their stars ascended his did not. Who knows why. In this film he is energetic, times his lines exactly, and knows where to look, as they say behind the camera. Television offered him a second bite of the apple and there he turned to directing and made quite a career of that.

Domergue, once a protege of Howard Hughes, played a scientist in a number of B sci-fi pics like ‘This Island Earth’ (1955), which is a keeper. There is pathos here because plastic surgery figures heavily in the plot of ‘The Atomic Man’ and she herself had extensive plastic surgery as a young woman when a car crash sent her through a windscreen.

The story is by Charles Eric Maine, who also did the screen play; he was a science fiction writer with little interest in and no knowledge of science. It shows.

He was really a detective writer who used science fiction conventions to set up his stories, and viewed against those expectations this film is worth more than the 5.4 rating on the IMDB. This film is not science fiction. The action turns around a nuclear research laboratory and that is it. He has a long list of titles ascribed to science fiction.

‘Starship Invasions’ (1977)

For those who thought ‘Battle Beyond the Stars’ (1980) was rock bottom, try this offering.

Leading the cast are Christopher Lee and Robert Vaughn. Quality right? Wrong!

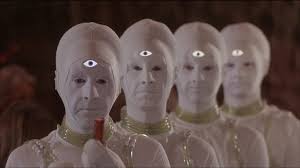

The acting is Easter Island stone faces. Lips not moving. Not moving?

The aliens are telepathic; ergo their lips are sealed. Most of the film shows expressionless actors staring at each other with a voiceover for the dialogue. Exciting stuff, not. This has to be the dumbest production decision ever made, well, apart from casting Tom Cruise in anything. Christopher Lee as the chief villain imitates a department store window mannequin in a black onesie with a hood over wires on his head to make him look even stranger than usual. That works. He looks constipated.

Here is Christopher Lee lips sealed ordering the destruction of the human population of Earth. Ho hum.

Here is Christopher Lee lips sealed ordering the destruction of the human population of Earth. Ho hum.

Even in the midst of a CGI spaceship battle the extras move like mannequins. An alien commander yells to his only underling, ‘Quick, shields up!’ The underling moves like he is underwater to the console, only to discover it has been sabotaged. That is quick? By the way, was this minion the one who failed to do the pre-flight check? After corporate downsizing, the alien is reduced to one underling. No backup.

Vaughn as a UFO scientist has a few lines which he manfully utters, but mostly the aliens read his thoughts. (I could read them, too, namely ‘Get me out of here! I am going to fire my agent!’) The UFOs whiz around, crash onto highways, are sighted by crowds of airforce personnel in a flyover, land in front the Toronto telephone exchange to steal some vital — as if! — computer equipment (1970s telephone routers, evidently picking up a few things for ET to use in calling home), and crash into the tower of the Bank of Montreal (which relocated to the safety of Toronto when the PQ won an election, and now this), while the authorities and media use alternative facts to deny the existence of UFOs. Faux News strikes again. That part is credible.

The one interesting idea in the screenplay is mentioned and then dropped. Early in the going Christopher Lee examines human DNA and concludes that his own race is the offspring of ancient Earthlings. Huh? How did that happen? But Lee puts aside such girly question and…villain that he is, does not hesitate for a moment to order the planetary extermination of his forbears. That intriguing idea was never mentioned again. It is treated in an episode of ‘Captain Future’ (1948) with far more energy and wit.

The Internet Movie Data Base offers a plot summary, which I do not have the will to do so myself. Yes there is a plot of sorts. The rating there of 4.0 seems high, though, as always, some liked it. That 4 is an average; some of the scorers gave it an 8 or so to balance my 1. (A ‘0’ cannot be cast. i know; I’ve tried.) Think about that. The only explanation of this celluloid muddle is the tax credits the Ontario government once offered foreign film companies when it laboured under the delusion it was going to create Onty-wood on the Mississauga. This cheap production was subsidised by Ontario taxpayers. Hence some of the supporting actors, like Vaughn’s screen wife, speak with the Ottawa Valley accent.

‘Battle Beyond the Stars’ (1980)

Another overblown and undercooked science fiction film with a sizeable budget is this entry: ‘Battle Beyond the Stars’ (1980), a CGI vehicle for John-Boy Walton, and little else.

The set-up is intriguing and there are some imaginative elements along with some major talents in supporting roles, but it is decidedly underdone. It transposes ‘The Seven Samurai’ (1954) directed by Akira Kurosawa to outer space via ‘The Magnificent Seven’ directed by John Sturges (1960). Though not credited the word on the web sites is that Roget Corman directed ‘Battle Beyond the Stars.’ That alone would explain why it is so lifeless, listless, and down right lazy. Kurosawa and Sturges could direct a script from the telephone book and make it interesting, not so Corman who could make ‘The Fall of House of Usher boring.’ Not could, did.

The imaginative element was mostly in the creature-features, always a speciality of Corman. There are several but the one that caught my eye was the multiple Nestor who got the only zinger in the dialogue — ‘We always carry a spare.’ In the context it gives chuckle. And the spare comes in handy. (There is pun there for the cognoscenti.)

Nestor(s)

Nestor(s)

And Nestor got the only really science fiction element in this shoot ‘em space western with the moving arm. But two moments in 1hr and 44m is too little.

The major talents are Robert Vaughn and John Saxon, both of whom play their parts with deadly earnestness, and George Peppard, who quite obviously wanted to be elsewhere, and should have been. Vaughn reprises his role from the 1960 ‘The Magnificent Seven’ as a world weary, no, galaxy weary, phaser-slinger, though what his particular talents are as a murderer for hire receive no explanation, nor is there any character development apart from his clenched jaw, and ennui filled sighs.

Vaughn and jaw.

Vaughn and jaw.

In contrast, John Saxon is a wonderful one-armed galactic villain! He is steely and focussed enough to burn through steel, as if this role were his chance at the stardom that eluded Carmine Orrico.

Saxon scowling.

Saxon scowling.

He does not drool nor scratch, but otherwise he has all the mannerisms of a major league Hollywood villain. He shouts at underlings, describes them as idiots, delights in torturing helpless victims, indulges his senses, devises impossible key performance indicators, cuts budgets, wait, he starting to sound like someone for whom I once worked.

A final confrontation between Saxon and Vaughn might have added up to something.

As it is, the crescendo, and I do mean crescendo because it is loud, of the movie is a twenty minute plus CGI shoot out that goes on and on, and on. (I did the crossword while the CGIs duked and nuked it out.) Peppard, Vaughn, and the Valkyrie, and finally Saxon get killed. At that point the film lost all interest for me, while the ever prepubescent John-Boy waxed on.

Did I mention the Valkyrie? No? What an omission!

Spot the Valkyrie!

Spot the Valkyrie!

She has to be seen to be believed. Roger Corman can do some things right and she is one of them. Sybil Danning, need I say more, the queen of B-movie babes who started her career, I do not joke, with ‘The Long Swift Sword of Siegfried.’ Lucky Siegfried.

The mystery is how Roger Corman got such talents to work for him as Vaughn, Peppard, Saxon, and, this time let us not forget, Danning. These players are way above his usual payroll. John-Boy must have had some influence.

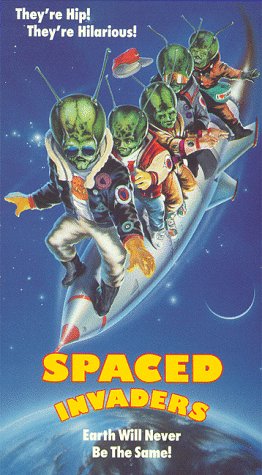

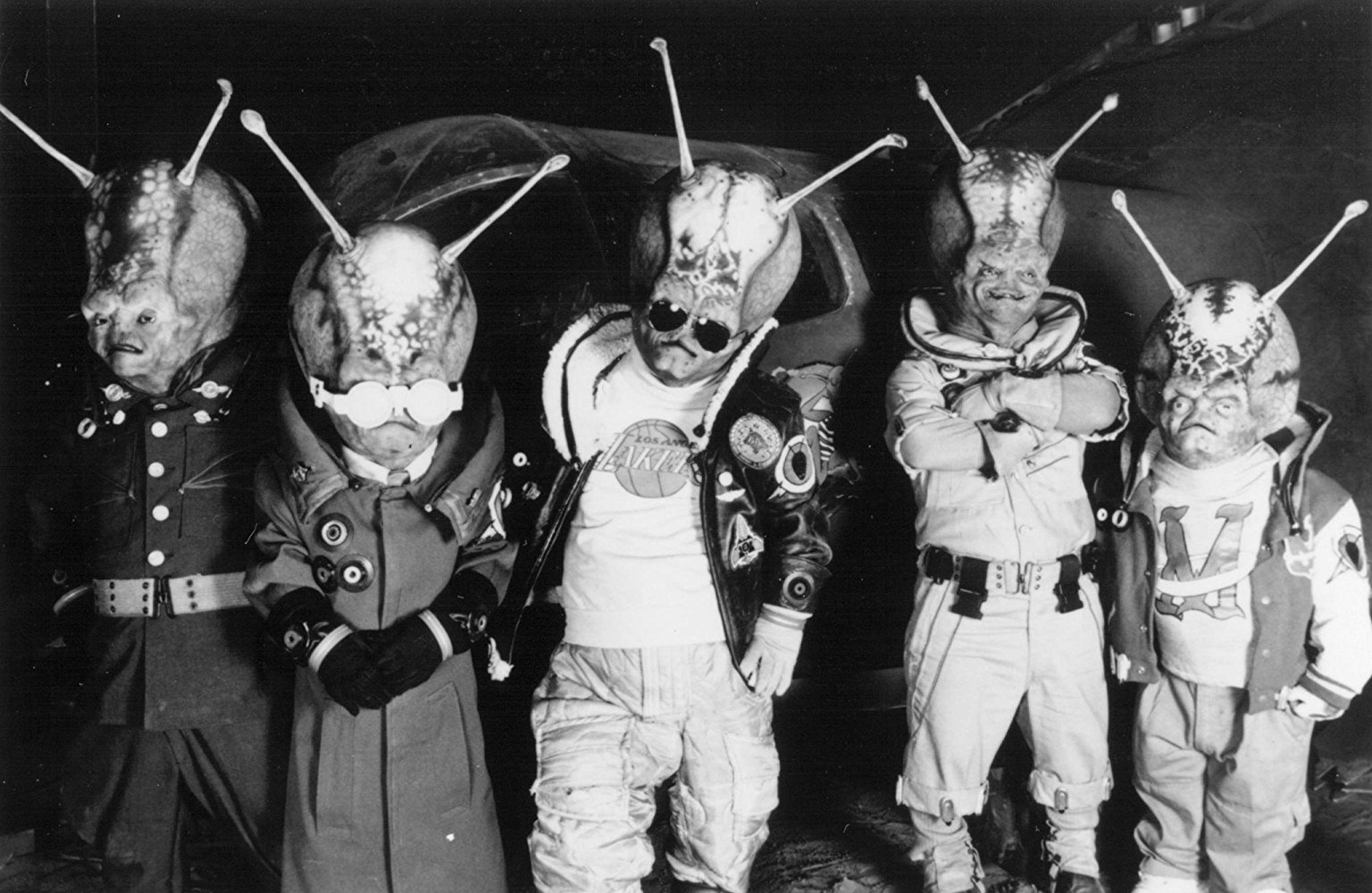

‘Dark Star’ (1974) and ‘Spaced Invaders’ (1990)

A pair of micro-budget parodies of big budget science fiction movies that offer more diversion than most of the films they mimic. Indeed while composing these bons mots I (tried) to watch ‘Saturn 3’ (1980) with Kirk Douglas and Harvey Keitel. It has a big cast, all that hair from Farrah Fawcett, and a big budget and set designs beyond the pale. It is pretentious and portentous. Now if it just had a story, a sense of humour, a purpose….something. I flicked away after twenty minutes. That the screen play was by Martin Amis probably explains all of that. (I tried reading one of his novels year ago, and it felt good when I stopped.) While enduring it I found a review from the doyen of reviewers, Roger Ebert, who mercilessly caned it. Amen, Brother Roger.

The ‘Space Invaders’ are the Z-team from a Martian armada bound for Alpha Centura. This hapless crew mis-read the map (upside down) and missed the fleet rendezvous (awoke too late) and is roaming around (lost in space) trying to catch- up, meanwhile exhausting the fuel. Think of those laggards with the Spanish Armada in 1588 who stormed ashore in Norway to… I was told once that the genetic inheritance from these dimwits explains both the swarthy genes and the stupidity of some Norwegians. It was Swede who passed the word on this.

While tooling around in the flying saucer the spaced-out invaders intercept a broadcast of Orson Wells’s ‘War of the Worlds.’ It being Halloween a local radio station is airing an old recording for the occasion. These dolts from space lock on to that signal and land in…Hicksville Illinois, blasters drawn and ready for a fight. It is Halloween so one and all are decked out as the weird and wonderful; ergo they fit right in. What if the Martians invaded and no one noticed? They did. They didn’t. Just as well because a dolt forgot to charge the blasters.

Moreover, the townsfolk are in an expansive mood because an off-ramp from the I-80 has been built which will bring untold tourist wealth to this dying farm town when motorists fill one tank and empty another. (Think about it, Mortimer.) A few odd little guys in strange costumes are most welcome.

The cast of small town inhabitants is marvellous. The wannabe dumb blonde who cannot quite conceal her superior intelligence but irony is not something much noticed. The shy gas pump jockey pines for her but she’s out of his league so he studies advanced physics journals between horn honks for service from the town bullies. The jostling among the local magnates to take credit for the off-ramp goes on in costume. Then there is Royal Dano, instantly recognisable and whose memorable name is never remembered, as a cantankerous farmer who is about to lose his farm to a slimy small-time, small-town developer.

Dano in conference with the Xers.

Dano in conference with the Xers.

Vainly trying to keep order in this mix — the farmer has a shotgun or two and the developer has a bulldozer — is the lantern-jawed sheriff whose ten-year old daughter really likes the costumes of the Martians. Upon discovering they are not costumes, she says, ’They’re not bad. just stupid.’ Very.

The Z-Team.

The Z-Team.

Delightful mayhem ensues. The off-ramp is offed. The developer loses his shirt and much else. The dizzy blonde figures it out. The gas pump jockey discovers the inner he-man. The angry farmer has the means to put things right. (Think silos.) With his help the Spaced Invaders might be able to catch-up with the Martian Amanda, or at least get to Norway and enrich the gene pool.

Segue.

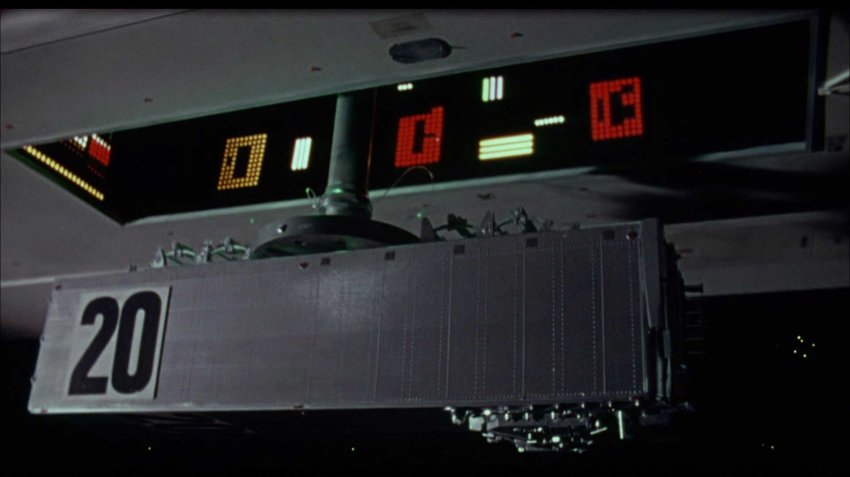

‘Dark Star’ started as a student project by John Carpenter who went on to bigger but not always better things.

It is refreshing change of pace from so many portentous and pretentious A and B science fiction films about the meaning of life or the end of the world. Oh hum.

This entry is strictly working class. Five grunts who share a disheveled and no doubt odiferous dorm room on a space scow go about their business obliterating planets with smart, and talkative, bombs. They are galactic garbage men clearing up the detritus. That the planets may or may not be inhabited is of no interest to them. The planets are in the way of West-Connex and have to be demolished to create a space route. Sydneysiders know all about this mega road project which is consuming whole suburbs in its path. It is the local version of Boston’s Big Dig and has been in the offing even longer than that behemoth.

Cinephiles will think of the later ‘Quark’ (1977), but Quark was not working class. A garbage scow yes, but piloted by the well-spoken, highly educated, very clean, and aspirational Richard Benjamin who hopes for a promotion and a better assignment. None of that fits ‘Dark Star.’ This crew has topped out with Dark Star. Their career and life trajectories are down, not up.

On board Dark Star an industrial accident has killed the captain but head office demands that the remaining crew press on, though the faults on the ship multiply, even as their budget is cut and cut again. Situation normal.

To relieve some of the boredom one member of the crew has a pet. Which tickles. Even in elevator shafts. Has to be seen.

Meanwhile, systems on the ship malfunction, but appeals to head office for permission to put in for repairs are denied. Off camera I imagined the suits in the boardroom suppose the ship, Dark Star, is beyond repair and that these working stiffs are expendable. The crew members are contractors, so there will be no payout to beneficiaries. Managers managing.

Indeed most of the events can be explained from the McKinsey management manual, though it is well before the Age of Managers Managing. Shiver! That would make a slasher movie.

It all finally comes to a head …. There is a Silver Surfer at end. Intriguing that.

Apart from the gung-ho talking bombs, and the tickler, another high point is the sound track, most of it written and some of it performed by John Carpenter before he turned his hand to slasher movies with which he made a killing.

One of the smart (-mouthed) bombs.

One of the smart (-mouthed) bombs.

Roget Ebert liked it and that is all I needed to know.

‘The 27th Day’ (1957)

A low-key science fiction movie about, oh um, the end of the world. The set-up is interesting, but it limps in the middle and reaches a puzzling conclusion.

A misleading lobby poster. There are no zapping flying saucers chasing Valerie French in a bathing suit.

A misleading lobby poster. There are no zapping flying saucers chasing Valerie French in a bathing suit.

Gene Barry with his experience in outwitting Martians from the red planet at the height of the Cold War in ‘The War of the Worlds’ (1953) is here, sporting a RAF moustache that looks so fake that we knew it would have to go and it did. Arnold Moss as the alien is so effortlessly grave that … [on him more at the end].

Five individuals from around the world – Chinese, Russian, American, Brit, and Dutch – are plucked from their routine and plonked into plastic chairs in a bland conference room looking very modernistic though not modern. There is nothing special about them, one a villager, another a sentry, a press hack, a sunbather, and a scientist. With gender diversity the Chinese and the Brit are women. The Dutch scientist is in fact visiting the United States, so that gives Uncle Sam two.

After having proven to the gathering that they are on a spaceship, Arnold Moss presents the dilemma. His planet is doomed and the population must relocate. These are planetary asylum seekers. The Third Rock will do nicely, but being pacifists, they cannot conquer though it is evident that their technology is far superior. Even big Gort seems a clumsy relic against Moss’s magic.

You have the power! (An early iPhone advertisement?)

You have the power! (An early iPhone advertisement?)

Apparently, neither can they negotiate. Instead Arnie will give each of the five a weapon (the size of an iPhone) that cam destroy their enemies. Note, it destroys only persons and not material. It works by thought control. If these weapons are not used by the end of the 27th day, the aliens will look elsewhere for suitable real estate and leave Earth alone, and the weapons will become useless. The explanation of the weapons is as detailed and as incomprehensible as McKinsey-speak but it covered every contingency the screenwriters could imagine, however, there is no manual for those who were not paying attention.

Knowing Earth history, it seems the aliens assume that some or all of the weapons will be used, and in effect that will depopulate the planet for their immigration. Rather like the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War stopping short of Paris, leaving the French there to murder each other and to save ammunition. Cynical. But then look at the news today.

During the briefing, Gene Barry gets the phone number of the English woman, clad in a bathing suit because she was plucked from the beach (hence the poster above), and then ‘Hey, presto!’ they are right back where they came from. She promptly throws her device into the sea, telephones Gene, and flies to LAX. She certainly has initiative and tenacity.

The Chinese woman, who says not a word and has no close-up, commits suicide. This seems to be in reaction to the massacre of her village which was underway when she was alien-napped. The cadre were practicing on the helots, they way they do.

The Soviet sentry is dumbfounded and keeps his mouth shut.

The Dutch scientist is on his way to a conference in New York City to which he now travels. Thus there are three possessors of this doomsday weapon and two of the devices are Stateside.

Sitting tight is not an option, because ….. Spoiler.

Because alien Arnold Moss goes on the air around the world on every radio and television channel in every language, he is more of media hog than the Twit in Chief. He tells everyone about the weapons and names the five who possess them. Cover blown! He had not told the five that he was going to rat them out like that!

The Feds latch onto the Dutchman as he lands at La Guardia.

Barry, having peeled off that moustache, thus disguised he grabs the Brit bit at LAX before the Forces of Order spot her, and together they head off to a hideout he just happens to know. (Probably cased it when dealing with those pesky Martians earlier.)

Pause for thought. Five randomly picked individuals have a doomsday weapon in their pockets. What will they do with them? That is one interesting proposition. Some will see parallels with the New Testament; I did.

Individual choice is quickly compromised by the public broadcast of their names. The Soviet grunt is arrested, suborned, tortured, but remains silent for a time. His motivation is left a blank. In the end, rather than see the weapon used he commits suicide by throwing himself out of an upper story window.

Barry and his girl puzzle over what to do in their hideout. The Dutchman, like the Soviet, keeps the secret…for a time. Though he is pressured relentlessly by the CIA operatives, but none of his inquisitors brought a waterboard.

The second interesting proposition concerns how others react. That an alien is at work becomes accepted by authorities and the public at large. The five individuals are then seen in the ensuing panic to be agents of the alien with Rush Limbaugh-like hysteria laid on. Imagine that! A man bearing a resemblance to Barry, remember that mo, is murdered by a mob. Add Faux News to that equation and the lynchings would be general.

Barry’s idea is to sit out the twenty-seven days, and by some miracle he and his squeeze seem to have enough provisions in the two bottomless grocery store paper bags they have to survive for the duration (of the film) undetected. Until….

Yes, the Soviet grunt finally cracks and the weapon is now available to the USSR, which promptly proclaims it to blackmail the USA to pull out of Europe and Asia. Uncle Sam complies.

This turn of events brings patriot Barry and Valerie out of hiding in the hour of need. The Western Alliance of the American Barry, the Brit bit, an the Dutch professor stall but time is running out. The Russkies know that the weapon will lapse at the end the twenty-seventh day so if it is to be used then it must be before then. To prevent a retaliation from the weapon(s) in the USA, the best time to use is just before expiration. The Cold War context weighs heavily throughout.

Meanwhile, Barry and company test the iPhone weapon app and it does indeed work. Ergo the compliance noted above.

But the professor has a trick or two up his academic gown. When Moss handed over the devices he said it has ‘the power of life and death.’ Significant that? He did not say ‘life or death.’ This egghead applies himself to re-programming the devices with his big brain so as to kill only ‘the enemies of freedom.’ Wow!

We all have candidates for that hit list. Think of whom Ayn Rand would put on that list. Try not to think of Rush Limbaugh. Try harder!

Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand

As the clock ticks and the Soviets prepare to activate the weapon app, the professor does his stuff and … that is it. ‘The enemies of freedom’ die! How easy was that! Lots of Russkies pile up in the streets.

In the aftermath at the United Nations there is an expansive spirit of unity of those who made the cut and Barry suggests offering the aliens some help. Maybe they could inhabit the parts of the Earth that are uninhabitable. The Antarctic is mentioned. New Jersey near the Kardashians seems logical? Some nice real estate in the Gobi Desert can be had for a price. This message is broadcast, and on the eighth ring Arnold Moss answers and rather than accept the offer instead welcomes the Earth into the community of 30,000 worlds! Whoa!

Huh? Was this some kind of fraternity initiation? That seemed to be the conclusion invited by Moss’s last remarks. Such a test for admission is a common theme in sci-fi but here it is explained no further.

The film drags in the middle with Barry and the Brit in the hideout listening to the radio. The minutes seemed like hours to them and to me, too. The whole exercise would have been much better in a half-hour Twilight Zone or Science Fiction Theatre episode.

A few notes. Two suicides. The voluntary production code that dominated Hollywood at the time forbade suicides in word or deed. Yet there are two here. The Chinese woman early on and the Soviet soldier near the end. Perhaps because they were both commies, they were better dead than red.

Both the women endowed with the weapon reject it. The Chinese throws it on the fire burning the remains of the village before committing Chinese-kari and the Brit throws it into the sea before flying to Hollywood, well, LA. Lesson? Never trust a woman with a weapon of mass destruction.

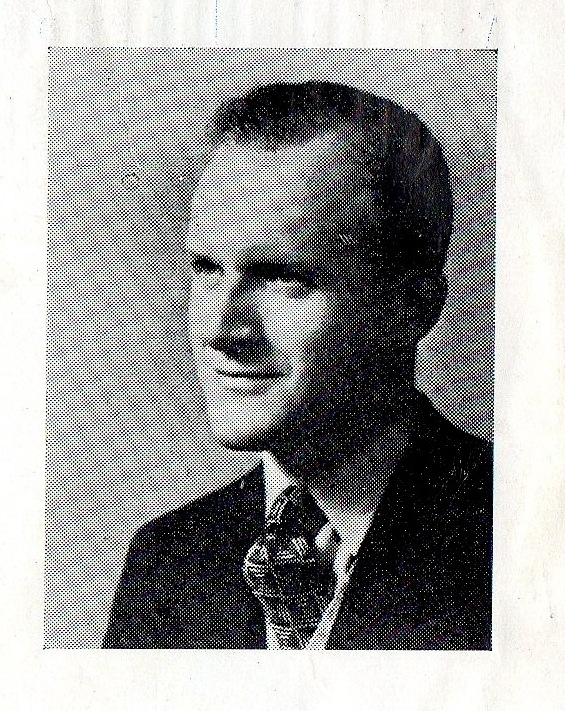

Arnold Moss (1910-1989)

Arnold Moss (1910-1989)

Moss appeared in ‘The Conscience of the King’ in ‘Star Trek: TOS’ as Karidian the executioner. With his aristocratic bearing, perfect diction, and melliferous baritone voice he always dominated any scene. Something (else) William Shatner complained about. Moss was Phi Beta Kappa with a Columbia PhD who constructed crossword puzzles for the ‘New York Times’ while waiting on sets.

Gervase Phinn, ‘Head over Heels in the Dales’ (2000)

Third in a series of novels about life in the Yorkshire Dales of England: Low key, rural, disarming, and downright charming. The eponymous hero is one Gervase Phinn, school inspector. Some will remember these (in)spectors who were often the object of fear and trembling.

Gervase is one of a team of four inspectors presided over by a senior inspector assisted by a secretary. This unit in turn reports to head office at the county. They are employed by the county but work to rules set by the Ministry of Education in distant London. Whatever the organisational chart, they are a small unit within a large organisation, combing the best and worst of each kind of organisation.

The master narrative is Phinn’s life and career. In this entry it is his second year on the job and in these pages he gets married to Christine and they set up house in a ‘builder’s delight’ of a cottage on the Dales, which are lovingly described.

Think of the countryside of ‘All Creatures Great and Small.’ Their efforts to make the cottage habitable are monitored by a neighbour who makes many observations, all of them laconic and most of them ironic, careful always never to lift a finger to help.

At work Phinn visits schools, sits in classrooms, talks to children, and attends one speech day after another. He also participates in staff development exercises at a training centre. The bulk of the novel strings together such episodes, many of which are delightful, as when a five year old girl in a class asks him how to spell ‘sex.’ No spoiler.

At Christmas he sits through four nativity plays in schools as he delivers the end of year reports. Dreary it may sound. Repetitive it may seem. But in the telling it is neither. The four plays are done in different ways, and Phinn, the writer, has the eye and ear for detecting those differences and conveying them to the reader. Wonderful.

At work the senior inspector and head of the unit, Harold, announces that he will take very early retirement in a few months, meanwhile a successor is appointed. In due course a much credentialed new senior inspector is named. Prior to taking up the job he pays several visits to the unit and the county office.

He speaks but McKinsey and talks but key performance indicators.

He bristles with changes and more change, and further change. Everything must change from the colour of ink in the reports to the number of rings of the telephone before answering. Everything must change from the time spent on task to the numerical indicators harvested from audits. Bullet points must replace text and text must replace bullet points. He is a very image of the modern major manager. As much as he is caricature he is also reality. In his hours of consultation, where he does all the talking, he never mentions children, teachers, schools, learning, or education. But the generic McKinsey-speak rolls on, and on. [Pause.]

Each of the members of the unit reacts to him. The Irish woman, Geraldine, is the first to realise the news is bad. Later when they catch on, David and Sidney are stunned into silence, an unusual state for either. Julie, the office secretary starts looking for another job. When this McKinsey clone refers to Connie at the training centre as the janitor, she …. and gets her revenge. She is the building supervisor! And proud of it!

The cast of characters is an amusing lot and given plenty of page time in the manner of all those character actors that enliven Frank Capra movies.

Lest it all seem light as air, note that there are serious moments. When David, with his usual insensitivity makes a stupid, sexist joke concerning unwed teenage mothers, both Geraldine and Connie set him straight in a one-two punch combination.

More than once Phinn is confronted by the conundrum of means and ends. The Ministry requires teachers to keep a tidy classroom, plan every teaching activity two weeks in advance, make written records of each class meeting, involve students in activities in prescribed ways, improve students language use and written expression in measured steps, and so on. This is the administrative approach to teaching much favoured by administrators and ostensibly it is the means to the end of education. Most teachers comply and most are adequate, and nothing more. Consider that approach applied to gardening for a moment to see it weakness. The plants are growing all the time in unplanned ways right now, not two weeks from now. A neat and well organised gardner may nonetheless have a dead garden.

But Gervase encounters in these pages two extraordinary exceptions. The first has a chaotic classroom in which the children do most of the talking as they explain things to each other. The room is untidy. Extremely! There is no plan. But there is excitement, curiosity, focus, learning, engagement, interaction, experimentation, argument, and more which the teacher seems to manage with hints and materials. It is all palpable but ineffable on the pages of the pro forma of the report Phinn must complete. Which is the priority? The Ministry standards or the children’s learning, because they are certainly learning, of that he has no doubt. Hmmm. Of the second deviant teacher there will be more in a moment.

Drafted to speak to a ladies’ club. He meets the president at her home where she orders her husband, Winco she calls him, to and fro like a wind-up toy. She blusters and demands and Winco complies with an amiable ‘Righto’ on each occasion. Phinn finds them both pathetic.

Only later does Phinn realise the Winco has every medal the RAF bestows, Distinguished Service Cross, Battle of Britain Ace, George Cross, two Life Saving ribbons, and others and that ‘Winco’ is short for ‘Wing Commander.’ Still later he learns that this woman was a Air Raid Warden with her own set of medals for pulling people from burning buildings while delivering babies in the rubble with the other hand. Never judge a book by its cover contra Bill Byson who never does anything else.

Gervase visits a Church of England school where all the most delinquent and troublesome students are sent within the high walls around it. Most of the teachers are rugby players. Most go through the motions with the sub-verbal, primeval slime they see as their students but are well organised with pristine paperwork. Phinn is shadowing one such amoeba who surprises him by her anticipation for the last class of the day, Religion. Huh? Well, he is not sure. She does not seem the sort to be ironic, but she is also difficult to understand mumbling through lip and tongue studs with a thick accent and three-word vocabulary.

Lo and behold! These students who have been indifferent and hostile in every other class that day, are completely rapt in Religion. The instructor goes at the Bible as though it were a football game, narrating the stories and eliciting reactions from the bleachers, and react they do! With four-letter words unusable for a family blog like this. Pontius Pilate gets a right barracking! At the end, they file out arguing about their reactions of events just unfolded. Engaged they are! Learning they have been, but how to square that with the Ministry pro forma? That is the question.

Gervase Phinn

Gervase Phinn

The book ends with a school fete and a verse reciting contest which Phinn must judge. His previous experiences at judging were none to happy. However deservingly obvious is the winner, the others have parents with a great deal to say. It is climatic, and great fun.

‘Gypsy’ (1999) by J. Robert Janes

It is Occupied Paris 1943, and a series of robberies demand the attention of the luckless duo of Louis St Cyr and Hermann Kohler. The robberies are bold, vast, and deft. But this is no mere thief because fatal booby traps have been left behind to discourage police investigation. Stealing millions of francs from a metro safe is of little consequence, but the theft of industrial diamonds bound for the Reich’s war machine is a red alarm, and our exhausted heroes are called in. Much has been said about them in earlier posts and will not be repeated here.

As usual no one will tell the the truth. As usual there are threats. As usual there are misleading clues. What is unusual is the audacity of the crimes, even high ranking Nazis in occupied Paris are been relieved of valuables they had just stolen from Jews! Audacious also in that three crimes were perpetrated in one night alone! Worse the booby traps have claimed victims, a chamber maid come to clean a room, a flic who opened a door, and a bomb disposal squad whose members should have known better. The villain also tries to eliminate St Cyr and Kohler; this a joker who plays for keeps.

The perpetrator, it emerges, is called The Gypsy, because part of his childhood was spent with some Romani people. Though he himself is tall, Aryan in appearance with the blond hair, and piercing blue eyes of a film star combined with multilingual charm and confidence. The irony is that his appearance and the Nazi uniform he wears, supplied by his would-be control, put him above suspension. His gypsy heritage ostensibly explains his preternatural skills as a thief.

Spoiler alert.

If I have grasped the plot, the Gypsy was in the slammer when the Nazis occupied Oslo. Then some bright Nazi spark had the idea of using him to infiltrate a Resistance network in France by inserting him as though he were an English agent. The connection would be made through a one-time girlfriend. What can go wrong? In return for exposing the Resistance network the Gypsy would be allowed to keep any loot he collected and sent on to Spain. (As if.) The members of the Resistance group he reveals would of course be tortured and murdered. The assumption was that the loot would come from the French, not Nazis themselves. So much for assumptions.

Once released, equipped, briefed, financed, and in France, however, the Gypsy pursues his own agenda. He slips his watchers, he manipulates the girlfriend into the frame and disappears. Then the robberies occur in rapid succession.

Now I may have gotten muddled because Janes’s elliptic style shows no mercy to slow wits. There is never a summation at the end in the Agatha Christie manner. But it seems the Gypsy had an earlier career of theft in Berlin where he stole from Nazis with great success until the Norwegians nabbed him. So far so good.

Meanwhile, the bright Nazi spark who loosened the Gypsy now tries to blame the crime wave onto (1) the Resistance and/or (2) St Cyr and Kohler. To that end this Nazi takes hostages, beats witnesses, and generally shrieks at one and all. If he cannot shift the blame, the axe will fall on him, no metaphor intended. Again I follow.

But what I do not follow is this. The Resistance network targeted was inactive, inert, and consisted of three well-meaning women who had done nothing and were never likely to do so. Nor did they have contact with others in the Resistance. They hardly seem a high profile target for such a far fetched and elaborate effort. That part I do not get.

Nor does the denouement make much sense to this reader. That these three women contrive and execute such a plan once the Gypsy shows himself is beyond my suspension of disbelief. That they nearly spontaneously concocted and implemented the plan is just not credible. They managed to out manoeuvre the Gypsy, the Nazis and the allied goons, and our heroes. If they were able to do that, well, why did they not do more for the Resistance?

Nor did I ever fathom what the Gypsy’s agenda was, apart form thieving for its own sake. He is simply a plot device in this outing and denied personality apart from one brief scene in the Metro.

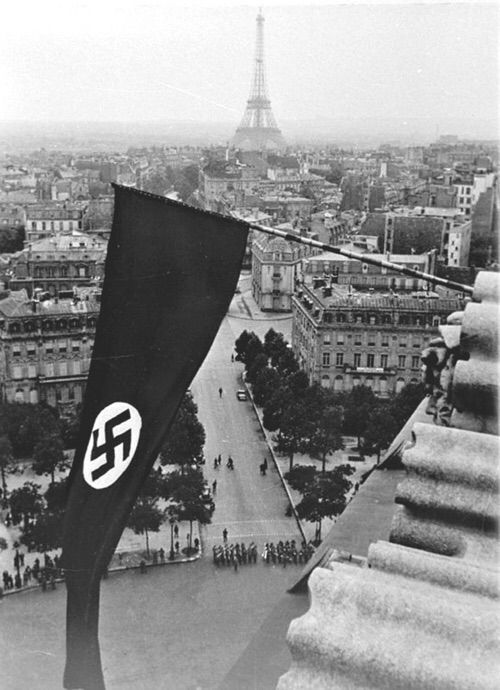

On the other hand, the siege of the hideout is marvellously told as is the evocation of Paris in 1943 when a Nazi victory seemed on the horizon.

As usual our heroes are full of angst! But as usual the reader knows they will somehow square the circle. These two will survive to the next volume in this long running series.