A detailed and comprehensive biography of the man, includes much of his family life and personal relations, as well as his long career as a diplomat, which started at his father’s knee. The trials and tribulations of his wife following him around Europe and the east coast of the United States, with repeated miscarriages and small children in tow is exhausting. What she put up with is remarkable and yet as the author intimates the norm of the time though exaggerated in the case of JQA.

JQA had three distinct but interacting careers, the first as a professional diplomat, second as the sixth president, and third, subsequently, as a Congressman for nearly twenty years. Throughout these careers he wrote and published poetry, and earned a little money from it, very little. There was no family wealth and he earned his own living and had constant money worries. One of the attractions of Congress after the presidency was the (pitiful) income.

There were many achievements in the diplomatic career, hard won though they were. He also did some noteworthy things as a Congressman. His least successful career was in the White House, and the poetry.

Because JQA spent so much time in Europe he saw, met, and mixed with many of the great personalities of the age including Napoleon, Wellington, Humphrey Davy, Russian emperors, Jeremy Bentham, Prussian generals, Italian inventors, etc. on his brief returns to the United States in Boston, New York, or Washington he mixed with the leading lights in politics (Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, John Calhoun, James Monroe) and inventors like Robert Fulton.

His diplomatic career started at age 13 when his father, in Paris to secure French support for the Revolutionary War, was sent to Russia to interest it in commercial contacts, and Adams Senior took along his prepubescent son, JQA, as secretary-translator. JQA has been schooled for several years in French in Paris and was fluent at his age level, and the language of diplomacy was French, and the language of the Russian court was also French. Adams Senior never learned any French despite his many years in Paris on several missions.

JQA’s last diplomatic posting was to Great Britain as ambassador. In between there was an array of appointments as minister (ambassador) to the Netherlands, Portugal (though this fell through before he embarked for Lisbon), France, Berlin, and back to Russia, and also many ad hoc missions to negotiate commercial contracts here and there. The most significant of the latter was one of the negotiators of the Treaty of Ghent to end the War of 1812.

The major themes of the book are:

Jefferson ran for president as the anti-Washington establishment candidate, as later did Andrew Jackson.

The French decadent and absolutist monarchy supported revolution but USA has much more in common with the more egalitarian, mercantile English. My enemy’s enemy is my friend.

Identification with France of the southern Jefferson and his embryonic democratic party versus the identification with England of New Englanders like the Adamses. The Jeffersons wanted a weak central government and strong states (to protect slavery) as the price of their adherence to the Union. The New England Federalist wanted a strong central government to hold the union together to protect rights and make for commerce. To the Jefferson democrats a strong central government was monarchical. Besides the tariff the only source of funds would be from the sale of western land, but the pressure was to sell cheap, not dear.

Tension between the human rights of the Declaration of Independnce the reality of slavery.

The effect of the 3/5ths counting of slaves allowed the south to dominate the House of Representatives where presidential elections were solved, and presidential voting.

Constant conflict between French and English involved USA as a bystander, the more so when Napoleon was active. JQA was in St Petersburg when Napoleon burned Moscow and in Paris when Napoleon returned from Elba and in a theatre when he appeared.

Impressing seaman from American merchant ships was a recurrent event. Britain was both desperate for manpower to blockade Europe and contemptuous of USA ability to stop it.

The idea of concurrent majorities that States had to agree to federal laws even regarding foreign relations, designed to keep the central government weak. To advocate local improvements meant federal government taxation to pay for those improvements. That meant bypassing state governments. Most federal income came from tariff on New England trade.

JQA had a brief term as a state senator in Massachusetts and also as a USA senator. In each case he had no chance of re-election because he did not vote exclusively for the immediate, narrow, short-term interest of Massachusetts.

Monroe made him Secretary of State and several previous Secretaries of State had succeeded to president. But by then JQA seems to have had no party. The extreme Federalists had abandoned him and the moderate federalists dissolved. The swarm of job seekers startled him.

His election was a result of the combined efforts of ambitious others who wanted to stop Andrew Jackson. They (Henry Clay, John Calhoun, William Crawford, and Daniel Webster) threw their votes to JQA. Jackson had the most popular votes but lost. In those days elections without a majority of electoral votes went to the House of Representatives where the anti-Jackson’s combined for JQA because he had no future. He had no party, no constituency, no ambition….

The intellectual, Indian-loving Adams had no chance the second time against the man of the people Andrew Jackson. Calhoun swung to Jackson. Crawford died. Clay huffed and puffed. Webster had less influence than he,thought. The anti-Jackson coalition split. JQA followed his father as a one-term president. He was comprehensively defeated. Like John Tyler and Millard Fillmore later, and perhaps Teddy Roosevelt, he was a president without a party. He started as a Federalist and served in Congress first as a Republican, then a Democrat, and Whig as president and in his last stint in Congress.

Though JQA thought parties perverted democracy with deals, compromises, and coalitions, yet he rejected the direct democracy implicit in the nullifiers position.

Indian-lover because he tried to honour existing Indian treaties. The slave states suspected him to be a closet abolitionist though his attitude to blacks was ambivalent.

Haiti and it’s black government loomed very large in the minds of slaveholding Southerners. They would not support any meeting of Latin American States that included Haiti.

Like Monroe before him, President JQA did not rush to recognise rebellious Latin American countries.

Adams is credited in these pages with writing the Monroe doctrine. Even if he wrote the words, which are quite matter of fact, not declamatory, it was always and only Monroe’s decision.

Major achievements of his presidency were peace and prosperity. He negotiated several boundary disputes on the Maine border with England, and also commercial treaties to keep shipping open. More important, he negotiated the Spanish out of Florida. Domestically he proposed many internal improvements, some of which were successful, but most were rejected.

While president he planted about 200 trees on the White House grounds, sometimes doing the work himself. It seems to have offered an escape from the unremitting and thankless job, as he saw it. He did not enjoy the politicking and working on the grounds also hid him from the press of job seekers.

As many as eight states proclaimed nullification of Congressional acts that did not suit them. The most obstreperous were, no surprise, Georgia and South Carolina. JQA always saw this as code for slavery. He never seems to have challenged slavery in any way, though, in the first two careers.

When he left office he was 64, and not robust. Yet when a retiring Congressman from Plymouth suggested that JQA bid for his seat, he was easily convinced to do so, despite the protests of his wife and grown children. He may not have like politicking but he still had a case of Potomac fever. He said going into Congress would allow him to speak his mind of the great principles without the onerous duties of the executive. I translated that as ‘I will have the satisfaction of carping at Andrew Jackson even if no one listens.’ The author takes him, on this as with everything else, at his word.

JQA was interviewed by Alexis de Tocqueville.

In Congress he chaired the House committee on tariffs which the front line in the battle between the States over nullification. But more importantly, he became ever more committed to abolition and said so often, repeatedly, and well. He accepted the assignment to defend the Amisted Africans before the Supreme Court, and though the case was decided on a technicality there is no doubt his arguments left the Court no choice but to find for the defendants. It was a giant cause célèbre at the time.

Adams the Congressman in an 1848 photograph

He is also credited with steering the Smithsonian bequest into the museums we now know. Believe it or not, Ripley, the original reactions to the gift were to reject it. New Englanders suspected there was some nefarious trick to it by the English, while Southerners did not want anything to increase the size of the federal government. They both wanted to reject it. President van Buren wanted to take the money, disregard the stated purpose of the gift, and use it to buy votes in his re election bid by investing in worthless state bonds in Arkansas, Ohio, and so on. There was pressure from the Brits to use it as intended or give it back to them.

JQA, because he had no party and no future, was finally made chair of a committee to deal with it. His own goal was a national university system starting in D.C. But that would cut across States rights so it never started. He compromised on the establishment of the natural history museum. A fine result, I say, having visited Smithsonian museums not enough, but what a terrific struggle to bring them about. There were several later efforts to ambush it which JQA saw off. It all seems as frebile, selfish, and shortsighted as a curriculum committee meeting.

He died at his seat in the House of Representatives. He had become in his last years a tiger for abolition and a skilled maneuverer in Congress. The book ends there. There is no summing up, retrospective, legacy, score card of strengths or weaknesses.

He continued to write and publish poetry throughout his life, and also published many speeches and essays on topics of the day.

The book rests on a mountainous knowledge of JQA, thanks in part to his diaries. Perhaps because so much comes from that source, the book sometimes seems to see the world only as JQA did. Any alternative view could only be explained by bad will, thus Henry Clay is written off as a self-serving cipher, he who knew he had destroyed his career with the Missouri Compromise. So, too, for others like Calhoun, who never compromised on his (despicable) principles. Only JQA seems to have been animated by the greater good, oh, and President Monroe, too, but only because he made JQA Secretary of State.

The book gives a premium to what JQA wrote as the mark of the man, and much less to what he did, until his last Congressional career. But in one reading of these pages he abandoned his wife and family routinely, often in very difficult circumstances though he was anxious about it, in his diaries, he did it time after time in the name of duty (but might there not have been a different way). He was hardly ever there for his children and when he was it was to chide and restrain them. He seems largely friendless. The author refers to many people as his friends but there is no detail so they seem more like neighbors, acquaintances, colleagues. In Washington he was a profound outsider because apart for the preceding eight years as Monroe’s Secretary of State he had lived outside the USA. Yes, eight years in which he seems to have made no friends, nor found allies. A loner he learned to be in his diplomatic life and loner he stayed even in the hive that is Washington.

I found the book hard to read at times. Not quite sure why. Convoluted sentences, there were a few, but no more than in most books dealing with complications. There was a great deal of detail especialy about his family life, that did not add to a reader’s understanding of the man, but was repetitious. In the chronology another account of the wife, Louisa, fainting spells did not sharpen the picture of JQA. I know the author left much out but I wondered if there might have been more — left out.

Category: Presidents

William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur (1978). Part II.

The military career of Douglas MacArthur spanned bows and arrows at the start and finished with thermonuclear weapons. He lived in a fort in the Southwestern United States with his soldier father when Apaches attacked with bows and arrows and left the army in the atomic age.

Most of the things this know-it-all thought he knew about Douglas MacArthur turn out to be false, the product of unscrupulous journalism, red-baiting politicians, or dithering Secretaries of State re-writing history.

1. He did not exceed his mandate Korea.

2. He did not propose nuking China or anyone else while in Korea.

3. He did not provoke Chinese entry into the Korean War.

4. He did not defy civilian authority during that war or before.

5. He did not cower in fear from combat in World War II as in the disparaging phrase ‘Dugout Doug.’

6. He did not abuse his role in post war Japan to please himself.

7. He did not underestimate the Japanese before, during, or after World War II.

8. He did not indulge in personal luxuries in Manila before the Japanese invasion.

9. He did not indulge in personal luxuries in Manila upon his return.

The list could go on.

How did he get so vilified? Two major reason emerge.

First, in the politically charged environment of Washington D. C. he never did not fit any the conventional moulds, so he was denigrated at times by conservative Republicans, liberal Democrats, and all stations between with their obliging hacks in the press. At other times one or another of these combatants embraced him and that riled the others even more.

Second, he was aloof in person and did not court any journalist. With personal shyness, lifelong paranoia, and a propensity to magniloquence on many occasions he made an easy target for those seeking a cheap shot. (I always think of Bill Bryson when I think of taking cheap shots which just shows that it works because he has made a career out of it.) MacArthur was always good for copy.

Perhaps more important than those two points is the fact that there was the studied reluctance in his superiors to give him clear, concise, and unequivocal orders in crises. That master of multiple meanings President Franklin Roosevelt was the Grand Vizer of ambiguity during the siege of Bataan, allowing MacArthur to infer from his radio messages that support and relief were on the way when none was contemplated, let alone on the way. MacArthur passed these reassurances on to his embattled army and the desperate Filipinos. Accordingly he felt betrayed when no help came and that he had been tricked into betraying the trust of his command and the Filipino people. In this context it made sense for him to say ‘I shall return’ because it was a personal pledge since he no longer trusted Washington D. C. and neither did anyone else in the Philippines at the time.

It is a similar story in Korea but with a larger cast and with even more at stake in the age of atomic bombs. President Harry Truman, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff Omar Bradley, and Secretary of Defense George Marshall all individually communicated directly with MacArthur, as well as in combinations. Then there was the United Nations, and the twenty-three (23) allies to consider. The energetic Secretary of State was capable of sending twelve (12) signals in a single day. Moreover, each correspondent chopped and changed from one day to the next. And each of them was conscious of the impending judgement of history and so at times wrote for that future audience as much, perhaps more so, than for MacArthur, who also was aware of posterity and replied in kind.

The most haunting memorial in that city of memorials, Washington, D. C.

The most haunting memorial in that city of memorials, Washington, D. C.

On occasion their communications were phrased as orders, at other times as suggestions. Some communiques were laid out as alternatives, implicitly leaving the choice to MacArthur and when he chose he was then castigated for the choice. Often the messages were short, so short that the point was not always clear. Others were long-winded and contradictory. He asked once for a clarification of a short message and got back sixteen pages (16), written by a committee (the Joint Chiefs), which lent itself to any number of interpretations.

To return to that list of points above.

1. His mandate from the United Nations originally charged him to ‘unify Korea.’ He had had explicit instructions to drive ‘the enemy’ out of Korea from Truman. When it seemed he was about to succeed in those aims, the ambiguity went into overdrive because China stirred. One confusing, contradictory message after another came from his many Washington superiors who would urge him to do ‘anything necessary’ but ‘do not take any risks.’ Doing what was necessary had inherent risks. It was like walking a zig-zagging tight rope in the wind. Yes, Washington D.C. did change that mission but did not want to broadcast it so it was phrased obliquely. But MacArthur was never a man to take the hint. Once engaged he fought to win.

2. In desperation in 1951 he did propose using radioactive nuclear waste as a barrier to stop border crossing by Chinese armies. Crazy, to be sure and immediately rejected with clarity for once but he did not propose nuking Red China as routinely claimed since.

3. We now know that the Soviets and Chinese had planned the incursion long in advance. To organise and equip such a force took months of preparation. MacArthur’s provocation was to defeat the North Koreans comprehensively which was the mission at the time.

4. Whenever he had orders he could understand, he obeyed even if he protested and sometimes told the press so, which he should not have done, very annoying to Washington but not a fatal offense. The exception is Roosevelt’s order to him to leave Corregidor, abandoning the 20,000 Americans and 80,000 Filipinos of his army. He stalled, he temporized, he proposed alternatives, he pressed for reinforcements and supplies, he asked about evacuating the entire force, etc. The third time he was ordered to leave the message said a great relief force aimed at the Philippines awaited him in Australia. He took the bait only to find 300 American soldiers in Australia!

5. ‘Dugout Doug’ exposed himself to enemy fire repeatedly. In Korea on day four before he was assigned command he went to the front lines for an inspection. To see he stood erect with binoculars amid the huddled ROK soldiers who were reeling from one crushing defeat after another. In the South Pacific he joined patrols more than once risking his life and those of his aides and he watched kamikaze planes attack the ship he stood upon. In World War I he, a general, was awarded five (5) Silver Stars for personal and conspicuous bravery. What more could he have done but be killed. (By the way Manchester quotes more than one armchair psychologist who sees in MacArthur’s cavalier disregard for his personal safety a shade of Thanatos. The only way to live up to his father’s standard, they speculate, would be to be killed in battle.)

6. He was indeed a Caesar, an autocrat, who ensured that Japanese women got the vote, and every women who won an elected office while he was there got a letter from him with congratulations. This is one of his many enlightened measures of which we never hear. He redistributed land in Japan far quicker and more decisively than Mao ever did in China. He brought in John L. Lewis to create trade unions. Free public education came next. None of these measures represented the administration in Washington; it was his program.

7. Prior to Pearl Harbor, he asked for air power for Manila in anticipation of a Japanese attack. He also re-organized his command in anticipation. In battle he was cautious and careful. During his time in Tokyo he assumed the best of the Japanese. The effort to conciliate Japan, Manchester attributes to MacArthur personally, not the State Department, not the President.

8. and 9. He did use furnishings and trappings to impress others, but he had no interest in creature comforts of any kind, still less personal luxuries. He did not drink alcohol though he often held a glass at receptions he did not drink from it. Though he would deny nothing to his wife,

Jean, but she asked little. They both spoiled their son without stint.

It is also true that the frustrations of the restraint, vacillating orders, massive Chinese manpower, decaying ROK army, half-hearted allies, and unremittng Eurocentrism produced outbursts from him in 1951, and then he started making wild proposals, too often public, for bombing Manchuria, for transporting Chiang Kai-Shek back to the mainland, for blockading Russian ports in Asia… Over the edge, indeed. (Mind you he was 71 years old at the time.) Truman bit the bullet and relieved him of command in a way, unfortunately, calculated to be insulting and demeaning. But MacArthur remained so calm, dignified, and unchanged that his humiliation was invisible to everyone, except Jean who knew the man as no one else ever did.

MacArthur was now much more free to speak, and he spoke. Though he did not attack the Truman Administration head-on when invited to do so at a Senate hearing. He did refer to conspiracies, which good hearted liberals then and since dismissed as delusions….until the Moscow archives were read to show that virtually his every Korean message to and reply from Washington D.C. was transmitted verbatim to Moscow and onto Peking thanks to Messers McLean, Burgess, and Philby. If MacArthur’s tactics were less successful in 1951 than in 1950 or earlier it was partly because the Chinese and North Koreans knew what was coming. There are people who still praise in my hearing Kim Philby and his associates. There is no doubt that this intelligence led to many, many deaths that might otherwise not have occurred in the Korean War, and at the highest level it allowed the Chinese to out-wait the United States because they knew how divided, confused, and paralyzed Washington D.C. was.

But then he did become in 1952 what he had despised in others, a general who did not know when to shut up. He travelled the length and breadth of the United States and said, dressed in full uniform ranks of medals agleam, all manner of things to anyone who would listen. He became ever more inconsistent, volatile, intemperate, illogical, and shrill. He craved audiences and loved the applause and grew ever more extreme to get the former and to bask the latter, becoming briefly an incandescent Cold Warrior. Soon enough he destroyed his own credibility, but not before ensuring that Truman would not be re-elected. Indeed this last act of MacArthur’s life is pathos – his thirst for adulation led him to say anything to get the applause. He advocated bigger and more weapons, a swollen standing army, while cutting all taxes to the bone. But no more crazy than any Tea Party Republican today.

The conflict over command between MacArthur and Truman has a parallel in that between Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan, though Truman was no Lincoln, but then McClellan was no MacArthur. The giants in this quadrangle are MacArthur and Lincoln.

There were moments in the 1952 Republican convention when his name was bruited and then faded quickly but, much to MacArthur’s chagrin, Eisenhower was the people’s choice then and later. While MacArthur did not actively undermine Eisenhower, he disregarded him.

It is also true that MacArthur was an egomaniac, thinking most of the world revolved around him. Any hesitation, any demure, any criticism was taken personally and never forgotten. He was driven to live up to the Olympic grandeur of his father (as told to him by his widowed mother) all of his life. Perhaps that also explains the battlefield risk-taking. That comparison may also explain his eloquence for his father was a prolix autodidact.

MacArthur did not have the common touch of Dwight Eisenhower nor the love of the warrior that George Patton had, nor the humility of Omar Bradley, nor the modesty of Joe Stilwell. He was awkward in social settings, shy and reserved which made him seem icy. He did not visit hospitals to speak to his wounded like Eisenhower. He did not cry on the battlefield at the deaths of his men, as Patton did. He did not carry a rifle like Omar Bradley. He did not speak of ‘we’ when referring to his army as Joe Stilwell did, but always ‘I.’

He restored the corrupt Filipino oligarchy in Manila at the end of the war, absent any of the reforming zeal that he showed in Japan. Most of these oligarchs had been happy collaborators with the Japanese who abused their fellow citizens. There was no land reform, no vote for women, no organized labor introduced by MacArthur here.

He saw to it that Japanese Generals Masaharu Homma and Tomoyuki Yamashita were convicted and executed when their crime was to have fought MacArthur to a standstill.

The book is superb, representing years of research, facts have been tripled-checked and cross referenced. It pulls no punches about MacArthur’s many failures and faults. Failures and faults that seem intrinsic to the man who was Caesar out of time. Yet it also leaves the impression that he was a giant. In reading this book at times I thought of him as Achilles, mercurial, audacious, preternatural, sulking, personally loyal, and altogether difficult to deal with. MacArthur had no Patrocalous to act as a trusted buffer. He had subordinates but he, unlike, Achilles recognized no equal.

It is also superbly well written, finely judged, subtle, insightful, penetrating. The highest praise I can give it is that it stands on the same level as Robert Caro’s monumental studies of the years of Lyndon Johnson.

William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur (1978). Part I.

A fabulous book about a titan. It will take two entries to review the basics. This is part 1.

It is all there in the title, and I do not mean that word ‘Caesar.’ What I do mean is that it includes neither the definite article ‘the,’ nor the indefinite ‘an.’ MacArthur is beyond those mundane grammatical considerations: one of kind, sui generis. A giant and a midget in one. Astounding achievements combined with a pettiness that seems out of character but was not. He was all one package.

He was widely maligned after the Korean War, and had a lot of buckets dumped on him earlier in World War II. He brought much of this criticism on himself by his unending paranoia that everyone in Washington was out to get him, by his colossal ego in which he was always trying to live up to his father’s mythical reputation, by his absolute determination to see through whatever he put his hand to despite changing circumstances, by his use of moral arguments rather than military one to justify his strategies and tactics though these were genius, by his unsocial nature through which he preserved his mystique but held most people at a distance, by his completely one-eyed devotion to and utter dependence on his wife Jean. He was a hard man to like.

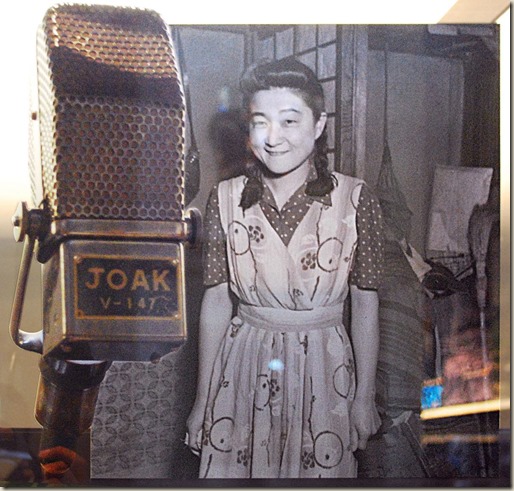

Yet, as William Manchester shows MacArthur was born to the sword though he never carried a weapon yet he was in battle time and after time. He led, he directed, he observed, but he did not pull a trigger. The exception is in Manila when Tokyo Rose

in 1941 broadcasted that Japanese squads were descending on the city to capture him and his family to deliver them to torture, ignominy, and execution. The aim of the broadcast was to frighten MacArthur and thus to show to Filipinos that not even their Field Marshall was safe.

Then he pocketed a revolver with three bullets, giving the rest of the bullets back to the ordinance officer to put to other uses. A typical beau geste from a man who made so many grand gestures that they became irritating. (Reader, tax that brain, figure out why only three bullets were necessary.)

He went over the top in World War I with riding crop in hand wearing the star of a general on his shoulders without either a helmet or a gas mask, he led patrols into No Man’s Land in the night, he stood in trenches attacked by Germans… Those exploits won him five Silver Stars for valor, each well deserved. But his theatrics drove Jack Pershing mad. No division commander should go on a patrol, go over the top, or even be in a front line trench, let alone one under attack.

When carpeted by Pershing and threatened with censure, MacArthur — clearly thinking of Douglas Haig who had never seen a trench, Joseph Joffre who bragged of not have heard a rifle shot, but not mentioning these Allied generals — said he wanted to see what it was like for himself and also it heartened the men to see a general sharing their risks and hardships. Pershing took that as an implicit criticism of himself and ordered him removed from command, Pershing forever joining the mental Enemies List MacArthur carried around for his whole life. As happened repeatedly MacArthur had arranged for his exploits to be publicized to acclaim in France, England, and the United States, and Pershing could not then censor a hero.

It gets worse because Pershing had commanded George Marshall to prepare the order for removal, which he did, and that entered Marshall’s name, too, on MacArthur’s Enemies List. Once on that list, there was no remission.

The occasions in World War II when MacArthur was shot at, bombed, strafed, sniped at, are all too numerous to mention. He exposed himself to enemy fire time after time, in a garrison hat with the stars of command visible. He was on the point with an Australian patrol in Borneo when the two officers with him were killed by enemy fire. An Australian captain pushed him down and screamed at him to leave. Chastened, he did. More Silver Stars came. He had a child-like delight in medals and awards throughout his life. Each one was precious to him. If the Sultan of Obscuria proposed giving him a medal, he wanted to have it. Yet he seldom wore them.

Leaving aside the details, which William Manchester assembles and presents in a compelling prose (without recourse to the adolescent present tense), the best testament to MacArthur’s military genius comes from Japanese war records. They show that they found him unpredictable, deceptive, cautious and bold, and never where they could hit him. In 1942 they thought he would give battle on the plain north of Manila, instead he withdrew into the Bataan peninsula with his forces intact in a move the Japanese described as brilliant. The Japanese had not expected that and were neither supplied nor organized for a siege.

The tunnel was the headquarters on Corrigedor, the island off the Bataan peninsula.

In 1944 he sewed confusion among the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific leap-frogging over their strong points (Rabaul, Wewak) and cutting them off.

Manchester shows that his casualty rate and use of supplies set against destruction of the enemy (Japanese soldiers incapacitated, area taken, time taken) was about ten times, yes 10 times, better than that of Dwight Eisenhower in the European Theatre of Operations, and 20 times better that Admiral Chester Nimitz (he of Saipan, Tarawa) in the North Pacific. The priority of Europe meant supplies were lavished on Eishenhower’s command, while Nimitz hit objectives head-on, signaling long in advance his next target – no subtlety there.

MacArthur would not have attacked a stupendous fortification like Saipan or a deathtrap like Tarawa but would have bombed and shelled each in a demonstration, and then leap-frogged over each to the next weakest island to cut their communication and supply. He would then have left them quarantined and boxed in. He put out of the war a dug-in Japanese army on Rabaul of 120,000 front line troops shipped there especially to give him battle by taking two barely defended islands north of it with the loss of some hundreds of casualties. Nimitz had 27,000 dead marines to take Saipan with its 80,000 defenders. The Japanese on Rabaul stayed there on ever decreasing rations until the Emperor told them to lay down their arms in 1945, so there was never a dramatic American flag raising on it like Iwo Jima, but then there was no comparable butcher’s bill.

On the offensive his many victories were often so quick and, in contrast to the gruesome backdrop of Tarawa or Saipan, so bloodless that they were even not reported back home, and did not enter the annuals as the great strokes they were. In fact, in the Philippines in 1944 he was criticized for moving too slowly by maneuver and not by head-on assault with the overwhelming fire power at his command. His response was public and clear, and as always in the first person: ‘I will take any objective I can by maneuver and feint to preserve every life I can, and I am sure that mothers, wives, sisters, fathers at home want it that way.’ We can be pretty sure the Grunts agreed. But for him to call a press conference and answer criticisms in this way was JUST NOT DONE! But that was the MacArthur way, his way.

Saipan

Like Napoleon at Waterloo, Lee at Gettysburg, or Haig anytime, MacArthur blundered. There are many recorded instances of very successful generals in the midst of a crisis lapsing into nearly a waking coma. Napoleon at Waterloo stood silent for hours, not replying, seeming not to hear the reports and requests of subordinates, which grew more and more urgent. Lee at Gettysburg seems to have entered a trance after he gave the order for Pickett’s Charge early in the morning and stayed that way for the rest of the day, even though it was clear things were going wrong even before Pickett’s men moved into position to carry out the order. Who can wonder at it?

The pressure, the burden these generals had borne for so long, the momentous events before them, the responsibility of the blood, these would crush most of us.

MacArthur had such moments, too. During the New Guinea Campaign, he had tried everything to avoid a direct assault with aerial bombardments, naval attacks, feints around the island, commando raids, and none had sufficed. Time demanded action before the Japanese could be reinforced. The result was the Kokoda Trail. No Australian needs to be told about this battle (though the spellchecker does not know it) in which nature took five (5) soldiers for everyone lost in action. While it raged in conditions straight out of Dante’s Hell, MacArthur had such a comatose period when he seems to have tuned out, sitting at his desk at times like an effigy of himself, silent, motionless. He was impervious to the explanations of General Robert Eichelberger about those conditions; he never stirred himself to examine the ground; he barely spoke to the Australian General Thomas Blamey whose troops did the foul work; he seems almost to have been in denial that it was happening. For MacArthur to sit quietly for hours on end was extraordinary because he was usually a restless pacer, either on his own, thinking, or with a retinue of subordinates. In fact his office space was chosen to allow him to pace, as was his accommodation. For him to be sympathetic and attentive would have made no difference whatsoever to the ordeal that had to be endured, but it would have been human.

This is the first of two parts.

I read this book in my Presidents Reading on the grounds that MacArthur, like Eisenhower after him, had many supporters who pushed him as a candidate, first in 1944 and again in 1952 after President Harry Truman dismissed him.

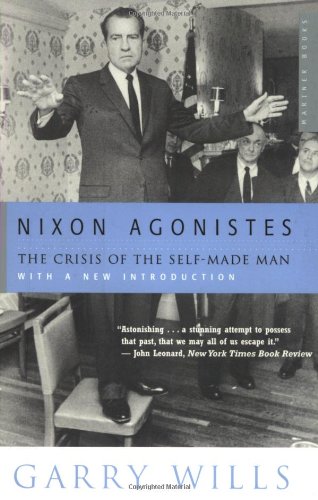

Nixon Agonistes (1968) by Garry Wills ****

A wide ranging study of Richard Nixon — the man, the career, and the times that shaped both the man and the career. It is uncanny in the way it a foreshadows Nixon’s self-destructive impulses: his paranoia, his introversion, his secrecy, his distrust, his self-doubts, his insecurities which combined to lead him to Watergate’s half-truths, deceits, prevarications, denials, lies, enemies list, and so on.

The Nixon that emerges from these pages is hardworking, and always over-prepared for everything, a man who scripted and edited his every word and gesture. If he seemed wooden and without spontaneity it is because he was his own puppet master, jerking the wires to jaw and arm. Supposing himself to lack the assets of others (the personal charm of Charles Percy, the grace of William Scranton, the wit of Adlai Stevenson, the courage of John Lindsay, the gravitas of Robert Taft, the respect accorded Dwight Eisenhower, the dignity of George Romney, the mental agility of Harold Stassen, the experience of Henry Cabot Lodge, the wealth of Nelson Rockefeller, the good looks of John Kennedy) Nixon compensated for all these these gifts bestowed on others by working longer and harder than anyone else with that famous “iron butt.” Everything he ever did in public was practiced, rehearsed, revised, practiced, rejected, redone, and so on until he reached the robotic result we all saw.

He would never give in to the human impulse to look at his watch while listening to a voter rant as George Bush (once did and was excoriated for so doing).

If Nixon throughout his career looked tired it was because he was, not having slept but instead planned, edited, and revised the next day’s every word and gesture. Nixon never trusted himself still less anyone else. This deep-rooted sense of inferiority seems to have come from nowhere; his childhood and family life before politics are numbingly ordinary.

As early as 1952 Nixon supposed that even members of his own party despised him (for his lack for such gifts as mentioned above) and this conclusion made him all the more determined never to put a foot wrong. One result of this determination was his distinctive reluctance ever to say anything in his own voice; instead he would say: “as a voter I met in Arizona said…,” or ‘as President Eisenhower said…,’ or ‘sources close to the Prime Minister said,’ and so on. It is likely that the first few times these attributions were true but in time it became a habit to distance himself from himself. Wills describes how Nixon reacted to his own successful nomination in 1968 as an example. Convincing.

Nixon leaving the White House after resigning, giving his victory gesture. ‘Victory?’ Nixon-logic.

Then there is his first inaugural, an embarrassing parroting of Kennedy’s, as if somehow to capture that magic. This Nixon reminds me of Kenneth Widmerpool when Barbara Goring poured the sugar bowl on his head (or the earlier banana incident); he was grateful to be noticed: even if as a fool. (Widmerpool is the central character in Antony Powell’s magnificient twelve volume novel, Dance to the Music of Time.)

The chapters were magazine articles on the 1968 US presidential election, and so range far and wide. Only three focus on Nixon, but that is plenty. There are also delicious accounts of Barry Goldwater, a man who loved his country so much he refused to saddle it with a lightweight president and campaigned to lose, and lose he did, and Nelson Rockefeller, a Hamlet of presidential politics whose fortune blunted his competitive ambitions and yet who later sacrificed himself rather than jeopardize President Gerald Ford’s nomination. The abiding hatred of Goldwater (acolytes) for Rockefeller is visceral. Apart from that noble sacrifice, Rocky’s finest hour was facing down the Goldwater mob in 1964. It can found on You_Tube as ‘Nelson Rockefeller denounces Republican “extremists” at the 1964 Republican National Convention.’ Those whom he denounced now run the joint.

Though it has nothing to do with Nixon, I particularly enjoyed Wills’s deflation of some of Arthur Schlesinger Jr’s many pretensions. That made me wonder how they cooperated when Schlesinger commissioned him to write the brief biography of James Madison (2002) in a series. Time may have healed that wound.

Wills, for those who do not know of him, is a master stylist, a seeker of facts, an insightful observer, a staunch Catholic, a self-described conservative, a ruthless diagnostician, an astute evaluator, an honest broker among competing ideas, a measured concluder…. He also has tangentites, a condition the spell-checker does not recognise but readers do. Sometime he can neither stop nor get to the point. That combines with some very Jesuitical logic-chopping that seems pointless, albeit spirited. At times he seems determined to find fault in anyone who takes a position, this the luxury of the journalist who never has to do anything as vulgar as come to earth.

Garry Wills

‘Agonistes’ is Greek for contestant.

In 1969 Wills refers to ‘men’ when he means ‘people.’ This will outrage anachronistic style police. I found it distracting and annoying,

Harold E. Stassen: The Life and Perennial Candidacy of the Progressive Republican (2013) by Alec Kirby, David Dalin, and John Rothman

Harold Stassen (1907 – 2001) sought the Republican nomination for president 13 times between 1940 and 2000. Surely an entry there for the Guinness Book of World Records.

By the 1960s his perennial candidacy had become a national joke, but there he was all the same, joke or not, shaking hands, smiling, talking to whoever would listen. The fact is, though, he did two things no one had ever done before and which everyone has done since. He explicitly declared that he sought the 1948 nomination in 1946. There are two points here.

(1) That he overtly and explicitly said he wanted the nomination. In those days the myth was that the parties sought the nominees who waited for the call, not that the candidate sought the nomination. Stassen did. Moreover, he did it two years in advance. Again, unprecedented. No one before had ever before admitted to the ambition so far ahead of schedule, though someone like Henry Clay in the 19th Century worked four years in advance to get nominations, he never admitted it.

(2) That Stassen would contest for the nomination through the primary election. That was likewise unprecedented. Though primaries had a long existence after the waves of the Populists and Progressives at the advent the Twentieth Century they were an empty ritual at the top of the ticket. State party committees decided whom to vote for in the national nominating convention. Stassen, lacking the connections of rivals like Senator Robert Taft, the public profile of General Douglas MacArthur, and the tested staff of Thomas Dewey, based his campaign on winning primary elections. The delegates he won would not secure the nomination, went the reasoning, but the publicity of winning and the press coverage would convince state party committees that he was a winner and they would switch to him. Stassen entered every primary going and ignored the state Republic Party committees in each one of them. Not a good longterm strategy but one he persisted in. These committees then retaliated by arranging primaries so as to disadvantage upstarts like Stassen. Yet he never learned from this feedback.

Now both these steps are common practice. Aspirants start organizing and fundraising years in advance and they admit to it, if reluctantly, and they work almost exclusively through the primary election calendar.

Stassen was — wait for it — a liberal Republican. Is it any wonder that his name cannot be dredged up on the Republican National Committee’s web site. In deference to the Tea Party zealots the Republican Party continues to delete its own history, erasing Herbert Hoover, George Norris, Thomas Dewey, Arthur Vandenberg, John Lindsay, Wendell Wilkie, Earl Warren, Margaret Chase Smith, Henry Cabot Lodge, Nelson Rockefeller, Jacob Javits, Olympia Snowe, Arlen Spector, Nancy Johnson, Christine Whitman, along with Stassen.

In Stassen’s time and place, being a liberal Republican meant: (1) internationalism rather than isolationism, (2) pro civil rights, and (3) cooperative with organized labor. Anti-communism was a given for all concerned. Internationalism meant working through the United Nations. Recognition of civil rights and organized labor meant not assuming that every black or trade unionists was a communist. He always referred to himself in that way, a ‘liberal Republican,’ yet the authors change that to ‘progressive Republican’ for reasons best known to themselves.

Stassen’s early career seemed charmed. He went from country attorney, an elected office, in 1938, to governor of Minnesota at 31 years of age, without seeming effort, defeating an entrenched incumbent.

When he was 33 he was the keynote speaker at the 1940 Republican national convention, and that gave him a national profile, and he caught Potomac Fever, and never recovered from it. (Other keynote speakers have later become nominees, think William Jennings Bryan or Barry O’Bama.)

He easily won re-election as governor in 1940 and 1942. That was his last elected office at 35.

In 1946 he declined to run for the Senate from Minnesota when he returned from the Navy so that he could concentrate on that presidential run in 1948. (His 1940 campaign was the creation of a few supporters at the nominating convention inspired by his keynote address. His 1944 candidacy was managed by Minnesota supporters for as a serving naval officer he was forbidden from political activity.)

President Franklin Roosevelt appointed him to the American delegation of six to the San Francisco deliberations that created the United Nations, of which Stassen remained a lifelong advocate. He worked closely with Doc Evatt at the time.

In the 1948 Republican nominating convention he finished third, behind Thomas Dewey and Robert Taft. To block the anti-labor, isolationist, anti-civil rights Taft, Stassen supported the cool and aloof Dewey who went on to lose the unloseable election to Harry Truman.

Between 1948 and 1952 Stassen served as president of the University of Pennsylvania, one of the Ivy League universities. He brought to the job a reputation as a good organizer capable of working with a variety of people and a national profile. His mission was to raise funds for the University. He took the job on the condition that he would continue his political activities. This was never a good idea, and it failed. Though it should be said that he somehow managed to protect Penn from the Red-baiting witch-hunting of the self-appointed anti-Communist crusaders who purged professors at Columbia, Harvard, and Brown.

In 1952 he supported Dwight Eisenhower against Mr. Republican, Robert Taft. But it was not clear whether Eisenhower would leave the army for politics, Stassen’s support for him also positioned him as the fallback candidate if Eisenhower declined the honour. Eisenhower did accept the nomination and won the subsequent election.

President Eisenhower appointed him to several administrative positions, which he handled well.

There follows all those other campaigns that seem like those action film stars today who keep slugging it out with Computer Generated Imagery in their 60s. He never seemed to learn from his failed campaigns and tried to do the same thing again next time, until it just became a habit. Perhaps those effortless early successes convinced him a destiny awaited, and he kept making himself available for the call. In addition to his quadrennial presidential campaigns he ran several times each for governor, Congress, mayor, and lost each time.

Stassen’s approach was low-key. At the podium he was an average speaker, but shone in question and answer sessions where he took an interest in what people had to say, no matter how many times he had heard it before or how uninformed it was, and responded in a way that communicated to the audience, farmers, factory workers, students, or voters on street corners. Likewise, he was an effective organizer and administrator who preferred to talk things over with people rather than pronounce glittering phrases that could be quoted.

Most of all, in hindsight, he is an example of that person who proclaims ‘40 years of experience,’ when the truth is that it is one year of experience repeated 39 more times. He never learned from experience.

In 1968 he was on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial when Martin Luther King gave that speech, having marched there with King (and many others). Full marks for that. Given the snide and gratuitous remarks President Ronald Reagan offered about Dr. King, it is doubtful that any Republicans these days would stand with him.

The obvious comparison is that other boy-wonder from Minnesota, Humbert Humphrey, who is scarcely mentioned in these pages. Humphrey did go into the Senate and as a result kept a higher profile than Stassen ever did after 1948.

The authors keep some distance between themselves and the subject, sometimes contradicting Stassen’s own assertions. There is also much evidence of archival research. That said, I found the book hard going. It offers neither a chronological nor a thematic approach but goes back and forth between the two. It is not a biography, despite that subtitle — ‘The Life…’ — and so we never learn much about the man behind all the activities which are listed in pointless detail. The repetition suggests that the chapters were written by different co-authors. Furthermore, three-quarters of the book concerns the years 1944-1956, twelve years of his four score and thirteen.

Nor is it clear how Stassen made a living as a perennial candidate who took unpaid leave to campaign. Who paid for the buses and planes in his campaigns after 1952 is never mentioned. Did he have a core of financial backers, or just one, like Newt Gringrich, who will pay any price continually to have a message delivered, however badly? Then there is the question of his wife, whose name is mentioned now and then, and nothing more.

I met Harold Stassen in 1960 without much of idea of who he was. One of his earliest and most loyal supporters lived in Hastings and Stassen came through when campaigning in the Republican primary.

The name stuck with me, though nothing else did except that he was wearing a wig, and I have now got around to finding out more.

The Presidency of James Monroe by Noble Cunningham, Jr. (1996)

Class! Who was the fifth Prime Minister of Australia?

Hum! Don’t know? Well, ignorance is no excuse. Write it down. Alfred Deakin served the fifth term, having done it earlier, and the fifth person to be sworn in as Prime Minister Andrew Fisher.

Now let’s try something harder. Who was the fifth president of the United States? What? James Monroe. Yes! That’s right. Did you peek at the heading? Of course.

Monroe was the last president to bear arms in the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). While in the Continental Army he warned against the vulnerability of the fledging capital Washington D. C. and proposed defensive measures, which were rejected by the Secretary War at the time, one John Armstrong. The British burned Washington in August 1814 and in September 1814 Monroe was sworn in as his replacement.

Monroe was the last president to bear arms in the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). While in the Continental Army he warned against the vulnerability of the fledging capital Washington D. C. and proposed defensive measures, which were rejected by the Secretary War at the time, one John Armstrong. The British burned Washington in August 1814 and in September 1814 Monroe was sworn in as his replacement.

Great Britain was much distracted by Napoleon réchauffé and made peace. Monroe was one of the commissioners who negotiated that peace at Ghent in Belgium before Andrew Jackson’s name-making victory at New Orleans. Monroe’s military, administrative, and diplomatic experience together with the patronage of Thomas Jefferson put a presidential stamp on him. There was some talk he would contest the office earlier but he stood aside for another Jefferson favorite, the diminutive James Madison who served two terms. (Monroe had been Secretary of State, had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, had been ambassador to Great Britain, to Spain, and much else.)

In 1816 Monroe’s time came. Though he was opposed because four the first five U.S. president had been from the Virginia Dynasty. (See if you can guess which is the odd man out.) Nonetheless, he was successful. At this time half of the state legislatures voted for candidates and then transmitted these votes to Congress. In the other half there was a popular vote which did not in all cases bind state delegates. If no candidate received a majority of electoral ballots, then the House of Representatives had a free vote. (All those idiots who idolize the Constitution as a sacred text without every having studied it, might consider this.)

In the event Monroe with the support of the outgoing President Madison and the living god Jefferson won. His re-election in 1820 was nearly uncontested, at least as much because the other major political party dissolved, the Federalists.

Monroe emerges from the pages of this book as a hard-working president who concentrated on foreign relations. This was an imperative because the United States was surrounded by European colonial powers. All were conscious that the United States offered an example of a successful rebellion against distant colonial masters that might be, and was, taken up elsewhere, particularly in Central and South American. There were the British in the Canada from coast to coast. The Russians had a toehold in the Pacific Northwest, while the Spanish claimed everything on the Gulf of Mexico from Florida to Texas, and all of the Caribbean Sea and California’s Pacific coast.

Monroe tried to divide these European neighbors with many separate negotiations. The Spanish were the weakest, and in time, thanks to the impetuous actions of General Andrew Jackson, they yielded Florida and the eternal supply of mosquitoes there.

Spanish weakness raised another specter and that was a French takeover. France rebounded from Napoleon’s second departure and its restored French Bourbon monarchy offered to regain Spain’s restive American colonies from Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, Argentina, and so on. The rumour was that Spain’s Bourbon monarch would transfer its American colonies to France, which would then dispatch a task force to raise the flag.

At the same time, an alliance between Prussia, Hapsburg Empire of Austria, and Russia was rumoured to be planning a move from Alaska into the Pacific coast to San Francisco.

There was a great deal of pressure on Monroe to support the several Latin American rebellions led San Martín, Simon Bolivar, Andre Marti. Monroe resisted this pressure and was criticized far and wide as a coward. (Nothing ever changes.) He was by no means sure how these rebellions would work out and if they failed, the Spanish with other European powers might take revenge on the United States which had proven incapable of defending itself in The War of 1812 a mere nine years ago and since Congress had cut military budgets by half every year… Yet the budget cutters in Congress called the loudest for a declaration of support for everyone, including Greece! (Nothing ever changes.)

Instead Monroe took his time and in a later State of the Union address he declared that the United States would not tolerate further European colonization in the Americas, nor tolerate a transfer of existing colonies to another European power. He was no Jefferson as a wordsmith, and the speech is guarded, qualified, indirect, and convoluted. The more so because the United States was hardly in a military position to enforce such an aspiration, it did by then, through some of those separate negotiations mentioned above, have a silent partner with such capacity and which partner did not want to see any other European power gain ground in the Americas. Class, see if you can infer which power that might be.

This assertion became known, thirty years later, as the Monroe Doctrine of the independence of the Western Hemisphere from Europe. It has been evoked several times since, by Teddy Roosevelt to warn off a German naval expedition to collect debts from Venezuela in 1904. Instead Teddy offered to broker an arrangement to deal with the debts which was accepted. The same had been done earlier (1865) and would be done later (1915) to impede French incursions into Mexico. Regrettably the Monroe Doctrine was also a cloak drawn over some unsavory shenanigans in Central America for two generations, and as a result became an object of resentment throughout Latin American by the time the Cold War came around. Then it was again cited, but by then its moral fiber was worn threadbare.

Monroe oversaw the reconstruction and furnishing of the White House after the British bonfire, and entertained in it at a punishing rate. Three to four dinners a week with 20-30 guests, a reception for 100 to 150 guests once a week. These occasions were all at his own expense but they were expected in a small town where there was little else to do. He was absolutely formal on these occasions. He did not particularly like this enforced society and he refused all invitations to visit others on the grounds of the dignity of the office. He was no communicator or glad-hander.

To manage the work of the office he made use of his family at no pay, his brother, his son, nephews, and cousins, while his wife and daughters managed the social side.

He maintained a strict neutrality in the election of his successor in 1824, which alienated all the candidates, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and John C. Calhoun.

Calhoun was his Secretary of War and he seems to have been a competent administrator with some strategic sense. It pains me to recognize any virtues in this violent and destructive man. It was his building program that led to the construction of Fort Sumter, later to be the flashpoint of the Civil War. Ironic that.

The petty bickering over personal and party preferment which characterizes Washington D. C. today has a long history. In 1817 when Monroe was to be sworn in the practice was for Senators to go the House of Representatives to witness the event in that chamber together with those who could fit into the public gallery once the Senators had been seated.

Henry Clay, a disgruntled candidate for president, was the Speaker of the House of Representatives. No friend of Monroe he. When the Senators proposed that they bring their own red leather chairs and put them on the floor to leave more room in the public gallery, Clay opposed this break with tradition. He was adamant, no red Senatorial chairs will ever sit in the House of Representatives!

Time pressed, and the result was to move the ceremony outside, where it has stayed ever since.

By the way, because of dispute over electoral ballots that changed nothing his second inauguration led to two days during which there was no president of the United States. Monroe’s first term, together with that of his Vice-President, expired on Friday 2 March per the Constitution at the time, but the dispute delayed his inauguration one day. For that one day, there was no one to exercise the presidential office. The succession arrangements in the Constitution at that time did not apply to such a problem. Then Monroe took the oath on Sunday, on which day it could not be communicated to Congress until Monday. The gap was then two days.

Monroe left office deeply in debt and the Congressional grant (in lieu of a pension) he had counted on covered less than half of it. He sold land and property (including tableware) to pay the rest. He died a poor man five years later, like Jefferson and Adams before him, on the 4th of July.

The volume is a part of series on presidents and it is confined to his presidency. Accordingly it does not mention at all Monroe’s support for the American Colonial Society’s efforts to transport freed blacks to West Africa, which became concentrated on Liberia, and in the city of Monrovia, as we know it today, which was given its name while Monroe was president.

The book is competent and thorough. It does stick rigorously to the presidency of James Monroe. It is not a biography then, and this reader got very little impression of Monroe the man, his family, his life before and after office. All of that is outside the remit of the series.

Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. 2d ed. (1982, 2007)

I read this biography in the American Presidents program I set myself. Eugene who? A president? He was a presidential candidate in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920, and my program extends to candidates, too. Some unsuccessful candidates, like William Jennings Bryan, are far more interesting than some successful candidates, e.g., Grover Cleveland. Both were Debs’s contemporaries.

The book sets Debs (1855-1926) in the context of his time, which was the Age of Robber Barons after the Civil War and reached national proportions from the late 1870s. In Debs’s experience this New Dawn played out on railroads and the unions of railway workers.

From the spread of the Iron Horse to the 1850s railroads were locally owned and managed. They usually came about from the combined capital and labor of men in a few small towns, hence the names of early railroads like ‘The Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe’ or ‘The Kearny, Grand Island, and Hastings Line.’ Businessmen in the three towns would pool their money and borrow from local banks to raise the investment capital and to hire and train labor from the same three town to build the railroads connecting their three towns. In boom times many did this and there were perhaps as many as 5000 of these independent railroads in the United States. See Steven Salsbury, ‘No Way to Run a Railroad’ (1982) for background.

Each railroad was a small business where the owners knew all the workers and vice versa, sat next to them in church on Sunday, stood by them at parades on the 4th of July, and sent their children to the same local schools. Accordingly, employer paternalism assisted workers, and workers made an extra effort to bolster their own towns’ fortunes for their employers. What was good for the Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad was good for Achison, Topeka, and Santa Fe and all those who live in those towns and work on that railroad.

This was the world that Debs entered as a high school drop out. (His bourgeoise parents wanted him to stay in school but he wanted the pocket money, and his strong will prevailed.) His aptitude for office work soon took him off the locomotives. Once he became a clerk, he also did the same work for the rail brotherhoods, these were philanthropic combinations that offered services to railwaymen, usually those injured, many started as funeral insurance funds. They worked closely with the paternalistic owners, and were often tougher on dubious claims than were the more socially distant and benevolent owners. Debs soon became a leader in these self-help associations, which were the seeds of trade unions.

Though there was much rail there was no national network, and there were few connections because gauges differed, the rolling stock was often locally made and so distinctive if not idiosyncratic, and so on and on. Despite the thousands of miles of track, it was still difficult and expensive to ship something from Omaha to Boston. Enter the Robber Barons. When recessions and depressions hit, they bought up these local lines cheaply and began the slow and expensive process of unifying the equipment, the organizations, the accompanying telegraph, and the labor practices. They took the ownership and control of railroads out of the hands of locals. Head office was now in New York City in the conglomerate that Was J. J. Hill, and not in the next pew on Sunday, or in the next chair in the barbershop.

Injured railwaymen, and there were many, were cast aside and newly arrived immigrants who would work for less were taken on, and in turn disposed of when they were injured. Try the Frank Norris novel ‘The Octopus’ (1901) for the gruesome details, far beyond the horrors of Stephen King’s imagination.

In this context the railway brotherhoods (firemen, brakemen, linemen, telegraphers, engineers, etc – these divisions among railway men proved to be as much the problem as the hostility of the Robber Barons) gradually moved to trade unions, the relationship between labor and owners becomes formal, attenuated, and belligerent, the conflict between those already there and immigrants added violence to the equation.

When conflict is unavoidable, per Salvatore, Debs shows an intellectual inconsistency and moral weakness in seeking compromises with the forces of darkness (CAPITAL) to deliver real, immediate, and tangible benefits to union members. Heaven forbid! He is as bad as these Sewer Socialists of Milwaukee who concentrated on building a clean and safe city for workers, eschewing class conflict for sewer lines and trams to carry labour to work, not to protest again capital. It is no wonder that these Wisconsin socialists have been nearly written out of left history.

Debs’s persistent effort to promote reform rather than launch a revolution, his willingness to ally with William Jennings Bryan and Teddy Roosevelt in the mainstream of electoral politics, his effort to use the ballot box rather than direct action or violent strikes, his penchant for citing Thomas Jefferson, Walt Whitman, or Harriet Martineau and not Karl Marx bemuses Salvatore, and is offered as evidence of Deb’s naiveté. Such is the view from Olympus.

Debs was a tireless labor organizer and speaker. The very few quotations from auditors that make it into these pages suggest he hectored, badgered, and brimstoned his audiences.

H. L. Mencken said he spoke ‘wth a tongue of fire,’ and I guess that is what he meant. Mencken is not cited in this book, though he was surely the shapest observer of his time, and he certainly had the serpent’s tongue himself.

It is sadly true that Debs was jailed, and sometimes beaten up by thugs in the employ of CAPITAL. But it also true that at times agents of wicked CAPITALISM asked his advice, deferred to him, and treated him with respect.

In time he became involved in the Populist backlash that the Robber Barons generated, igniting at the end of those railways in the Middle, North, and South west. He was mooted as the presidential candidate of the nascent Populist Party in the 1896 Presidential election, but Debs instead nominated William Jennings Bryan. To comrade Salvatore this flirtation with Populism and alignment with Bryan are proof absolute that Debs was dopey.

In 1912 he got 900,000 votes or 6%. This was the high water mark. The votes had no effect on the outcome: Woodrow Wilson won. Debs was last, behind both Teddy Roosevelt whose one-man party finished second and the Republican incumbent William H. Taft who finished third. But each campaign allowed this man, born to the priesthood, to preach across the nation. Though he was a very intense speaker, the book hardly mentions the campaigns.

Instead the book offers minute accounts of the faction fights, splits, divisions, competing agendas of the ever smaller number of socialists as each group sought perfection. Why did Socialism fail in the United States? That is a question often asked. The answer is right there. The search for perfection is the enemy of doing some good. Here’s an experiment to answer the question. Put three self-proclaimed Socialists in a room and close the door. A day later there will be five parties. The next day, eight splits. On the third day a revolt. [They never make it to the seventh day of rest.] See Seymour Martin Lipset, ‘Why socialism failed in the United States’ (1954), which is not cited in this book.

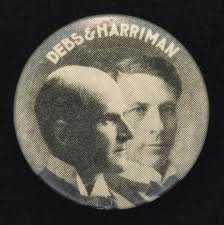

Debs seems to have changed over the years and been willing to change his mind, but the author regards that as a failing. Debs also seems to have been a hard man to like. Cold, distant, jaded with time, and thin skinned to criticism from fellow socialists. In 1900 his VIce-Presidential running mate Job Harriman, despised him and left for a four-week tour of Europe to visit socialist conventions rather than campaign for or with him.

Hmmm. That is commitment to the New Jerusalem but not today. Just the man for the job was this Job. He later found the workers’ paradise at Llano in the Mojave desert above Los Angeles where land was cheap for many good reasons, and when the apple was eaten in that paradise the group split he led some diehards to Louisiana to New Llano, a site I visited in 2004.

Debs had spoken vaguely himself of workers’ colonies in the West where the dreaded and dead hand of CAPITAL did not reach. But when Harriman tried it … [Guess!] …. Debs objected, and so did most other socialists. This was not the way to paradise.

I often wondered why our author or why Debs himself did not turn to the most insightful student of American democracy ever to grace a page: Alexis de Tocqueville. He would have had no trouble in explaining the failure of Socialism. The promise of freedom, the promise of individualism, even if only partly achieved is irresistible. In family pictures of immigrants from Bohemia, Schleswig, Bratislava in Nebraska in the 1880s they are dressed — to my eye — in rags, sitting in front of crude dugouts, with animal dirt in evidence, yet these people glow with pride. They own themselves in a way they never could have done in Europe. Promise fulfilled! Serfs no longer.

Slave-pay, barbaric work practices, grinding existence, a barter economy, hunger, are second place to that self-realization. A Robber Baron is a small thing in this light.

Debs never thought out a position on race. But he was early, loud, and consistent on women’s suffrage. Full marks on that one.

He was arrested during World War I for objecting to a war of nationalism while Woodrow Wilson was president. Though Debs was arrested by local authorities after the United States Attorney-General declined to prosecute a man for speaking his mind and doing so very carefully to avoid violating the law of the land. But a Federal District Attorney hungry for limelight proceeded anyway, and secured a conviction after stacking a local jury, while Debs seems to have welcomed this relief from pressures of the endless, unproductive, increasingly bitter faction fights which made martyrdom look good.

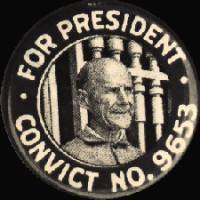

He was in a federal prison during the 1920 election when he got 915,00 votes, or 4% of the total.

Certainly a striking campaign button. The Debs Foundation offers replicas for $3.

Debs married young and grew apart from his wife who lived in their family home in Terre Haute Indiana which he visited on his coast-to-coast travels once or twice a year. He was hard drinker and this ruined his health, as did the nervous pressure of constant conflict among the self-styled socialists, and the rigors on nearly continuous travels. He was a frequent patron at brothels, and in later life, while remaining married, co-habited with another woman who seems to have admired him in a way his wife never did.

Being a secular man, I suppose, Salvatore spends not one word on the largest and most pervasive social force of that time and place, Religion. Did Debs have religion? Did he attend church? If not, did he express atheism or agnosticism? Unknown.

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 inspired many and they split the Socialist atom once again to create the American Communist Party, e.g., Emma Goldman, John Reed, Earl Browder. That was the end of Socialism. Debs himself was a spent force by then and let it slide from his prison cell.

He was jailed in Atlanta from 1917 to 1921, when President Harding, no doubt in his usual alcoholic stupor, pardoned him.

Having opened with references to Debs’s contemporaries William Jennings Bryan and Grover Cleveland, let us return to them. Debs was certainly the intellectual and moral superior to Cleveland however one defines these terms. He knew and saw more American life than Cleveland, and he had more contact with and learned from people he met, unlike the bumbling recluse Cleveland. Yet he seems a remote preacher shouting down from a pulpit compared to Bryan, who liked people whether in ones, or twos, or thousands and seemed to speak with rather than yell at them. Bryan’s message was God’s love and social cooperation, while Debs offered that brimstone of Socialist perfection that admitted of no exceptions.

In sum, he is a man born to the priesthood, who created, accepted, nay, welcomed his own martyrdom. In this portrayal he seems much less interesting than Herbert Hoover, Sam Houston, or Teddy Roosevelt.

For the Salvatore, Eugene Debs is the ectoplasm in which changing social forces played out.

‘Ectoplasm’ is the word for Debs in these pages, because the author treats him like a specimen on the slide of history, and not as a living, breathing, thinking, learning person. This is social science as biography, and least we forget, social science is about social forces that shape and make individuals. That is called Structure with a capital “S” in the lecture halls of universities. Hence the reference above to religion as a social force of the age.

When biography writers establish some distance between themselves and the subject, it affords them scope to be honest about the weaknesses as well as the strengths of the subject, but Salvatore’s distance is measured is astronomical hindsightyears. Salvatore knew all along that the Robber Barons were coming, that the conflict between capital and labor was foreordained by Brother Marx, Karl not Groucho, that class conflict would be the words to live by, and so on.

He disdains the rather dim Debs who had to learn some of these lessons through his skin. Debs, not Salvatore, was the one beaten on picket lines, but it is Salvatore who knows how Structure led to this beating. Salvatore’s Lefter-than-thou hindsight nearly buries Debs the man beneath an avalanche of class analysis jargon. I began to suspect that the book started life as a PhD dissertation in which the premium goes to the theoretical framework and not the data, the man in question.

Before conceding too much to Salvatore and his ilk, note that Karl Marx said that history makes man, but that also man makes history. It is a reciprocal equation, social forces make us what we are, but the script is broad, blunt, and imperfect and in those imperfections we Lilliputians make social forces what they are. Social life is an endless editing of the social script. I am using the metaphors of Brazilian political scientist Roberto Unger’s very original and generally neglected ‘Plasticity into Power’ (1987). (Do not be fooled by the long, laudatory entry in Wikipedia; his work is seldom cited in the halls of political science or law).

There is no question here, no tension in this book: Debs is a billiard ball bounced around by social forces he only vaguely perceives. But which forces Salvatore can name in an instant, such is the alacrity of a good student who knows all the words and little of lived-meaning in the life-world. (Apologies but I thought I would throw in some Germanic jargon from Martin Heidegger just to show that I could.)

Other presidential biographers smell the feet of clay in their subject without squeezing humanity out of them. Robert Caro’s distaste for LBJ is palpable in Volume II but he also finds Lyndon to be larger than life and sui generis, fascinating for it. Nothing is sui generis in the pages of this book. All is explained by social forces, which reduce to the evils of CAPITALISM. Get it! If not hand-in your class consciousness card at the door on the way out.

The book does not ever even try to bring him to life. Ectoplasm is a stain on a slide. It is the first biography I have ever read without a human subject.

After plowing through these pages I will seek relief in some pleasurable, escapist reading: Let it be Inspector Pel!

Grover Cleveland: A Biography of the President Whose Uncompromising Honesty and Integrity Failed America in a Time of Crisis (1968) by Rexford Tugwell.

After reading the condescending remarks about William Jennings Bryan’s lack of presidential intellect it was amusing to read this study of two-term president Cleveland who was Bryan’s exact contemporary. Bryan got by with the Bible for reading, Cleveland’s horizon did extend even that far. He never read a book and never opened an atlas. Never left the United States, and only made one trip around the country when president. For a politician he was nearly anti-social.

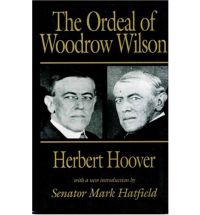

The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson by Herbert Hoover (1958)

This is a book about a president by a former president. It is unique and must reading for presidentialistas. It is all the more distinctive since Wilson was a Democrat and Hoover a Republican.

Could it happen again? Would a Republican Bush write a tribute to a Democrat Kennedy? Or a Democrat Clinton to a Republican Reagan?

The ordeal is the war and the peace of the Great War 1914-1917, though it only concerns the American participation in the War 1917-1918. Hoover was enmeshed in Europe from 1914 on in organizing food aid for first Belgium and then France, and from November 1918 onward for all of Europe as far east as the Volga River in Russia. It was colossal undertaking that just got bigger.

Hoover worked for Wilson in several capacities, directly and indirectly in these years and some of the work was very intense, urgent, and truly life-and-death. I have traced some of Hoover’s astonishing humanitarian efforts in the review of the Hoover presidential library elsewhere on this blog.

The book was written forty years after the events it describes when Hoover was in his twilight years.

There is no indication that Hoover kept a diary at the time but he certainly kept copious files. In addition to the papers he himself had, Hoover also consulted reams of declassified official files to which he had easy access and he was assiduous.