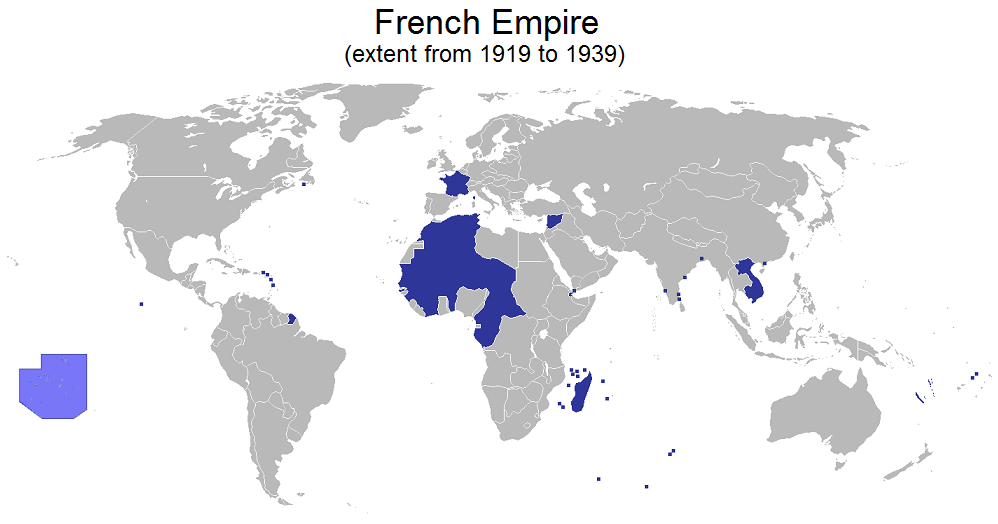

In 1931 the French army was the largest, best trained, most modern in equipment with a wealth of strategic intelligence in a large and able general staff joined to the leading airforce of Europe and a large navy with newer and more powerful warships than England or Italy. In addition the French Army had those kilometres and kilometres of tunnels, bunkers, turrets, gun emplacements, tank traps, endless buried telephone wires and underground cities of the Maginot Line. To members of the general staff of Germany, of Spain, of England, and of Italy, France was an impregnable fortress. Moreover, it had an even larger colonial army spread around the globe from New Caledonia to the Caribbean. In particular its officer corps was its pride. It was drawn from all classes of society, promoted on merit in a system that prized intellect.

It was altogether impressive, this army, and yet less than a decade later during five weeks in May 1940 this army was comprehensively defeated. So total was the defeat that it was embarrassing. The defeat was as much psychological as material. French troops fought with each other in the rush to surrender. Units far from the front abandoned their arms never to touch them again because of rumours of a truce before the first radio broadcast of a ceasefire. Officers, it was said, surrendered as quickly as possible so as not to miss lunch. Censors tried but failed to suppress pictures of lone Germans herding thousands of apparently willing French prisoners along. This moral collapse turned the army into a mob by the thousands. When the German burst from the impassable Ardenne forrest, the French army fell to backbiting and backstabbing at all ranks. For their part staff officers in Paris denied responsibility and knowledge of anything and everything in some squalid episodes.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

The surrender. General Gerd Von Rundstedt went on and on reading a long statement authored by Hitler to the French officers. There are many videos of this ceremony on You Tube.

Yet apart from some volcanic fighting in Belgium and around the Pas de Calais (Dunkirk and Ostend), the defeat resulted in relatively few French casualties, making it all the more surprising, and all the more embarrassing. In fact, French Army emerged from the defeat largely intact, though its members were divided, dazed, confused, isolated, dispirited, and exhausted. There is plenty of newsreel footage on You Tube. Have look.

Perhaps the analogy is to victims of a mighty car pile-up on an expressway.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

A poilu dazed, stunned, isolated.

Blind-sided, a gigantic wallop with noise and shrapnel, and than another and another as the pile up continued. Much noise and confusion but few killed or injured. Yet all are dazed and confused.

This book is a study of how one set of the victims of that crash, the officers of the French army, responded to the catastrophe. It is a subject that takes study, because the recriminations at the time and since have been a blizzard without end, as blame as been laid this way and that, often with no other evidence than the unshakeable conviction of prejudice. In fact, it is perhaps the kind of study best done by an outsider who is disinterested in the matter. This book is based on archival material, publications of the day, interviews with participants, and, inevitably, the river of memoirs protagonists wrote to justify themselves. It is impressive to see how much microfilm of contemporary records and reports in German and French the author worked through to find the confirmation or disconfirmation of assertions that in other books are taken as read. Through this minefield Paxton picks his way with care and sound judgement.

What prompted my interest in this study was the realisation, born of reading about this period, that the chain of command in the French army survived the triple debacle of June 1940 and remained in place for the use of the Vichy regime both France and in the colonies, triple in the defeat, the surrender, and the humiliating peace.

Remember, that this army was deployed around the world in French colonies, territories, protectorates, enclaves, embassies, and missions – most particularly in Africa and the Middle East but also in the Caribbean, India, Latin America, and Oceana, including New Caledonia, today a one hour flight from Brisbane.

As discredited as defeated France was, the colonies held fast to it in this dark hour despite the clarion call from London on 18 June, when Charles de Gaulle made his first radio broadcast in the name of France Libre. Likewise, the officer corps in France also obeyed orders to return to barracks or comply meekly with capture and imprisonment. As German archives show, they were themselves surprised at the speed and scope of the capitulation and unprepared for it.

Even as two million French prisoners of war were being entrained to Germany, the remainder of the French army began to demobilise itself. While de Gaulle shined a light, in the first months few officers followed it. This is all the more remarkable considering the residual anti-German sentiment throughout France and most particularly in the army after the bloodbaths of World War I, which had led to the development the formidable army described at the outset.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

One German guard and hundreds of French prisoners bound for slave labour in Germany.

Paxton’s focus is not on the defeat but the aftermath, though he does set the scene by showing how in the years after 1931 the strength of the army dissipated. There were disputes within the army over strategy and tactics that took the form of bureaucratic backstabbing and career blockage to new extremes. Charles de Gaulle was himself one of the victims of this battle.

Though French tanks and fighter planes were technically superior to their German, Italian, and English counterparts in 1939, the doctrines that dictated their use did not exploit the capacities they had: One example, Renault heavy tanks were technical leaders, and those the Germans captured were later used to good effect on the Russian front in the following years. But French army doctrine spread them very thinly through infantry regiments as mobile block houses for static defence. They were not grouped to give weight and supporting fire power in attack. The Germans, at the time, had lesser and fewer tanks but made far more effective use of them. The same could be said for aircraft. It is also true that often the French forces outnumbered the attacking Germans, but the tactics of the Germans with tanks and aircraft overcame the numerical advantage the French had. The French also enjoyed the advantage of shorter and interior lines of communication but again German tactics cut these by attacking roads and bridges from the air. The French airforce doctrine conserved assets and did not attack German ground targets.

Even more corrosive were social attitudes of those born to the army, and their scorn for parvenus, including Jews that had entered the army during the Third Republic, especially under the Popular Front government. It went beyond the usual snobbery or cliques one must expect and included systematic efforts to degrade, discourage, and drive such undesirables out of the army. There were many little Dreyfuses victimised in a hundred small ways for the lack of a ‘de’ in the name or the presence of ‘berg’. Contrary to the post-war legends there was little liberty, equality, or fraternity in the French army by 1939.

After 1931 successive governments cut defence spending, as did General Phillipe Pétain, when he was minister of defence, and cut it again, and again as the Great Depression spread. As the ordeal of World War I receded from memory, an historic anti-militarism in French society, a child of the French Revolution when the army was the instrument of royal oppression (and it was again with the Napoleons and restored monarchs), re-asserted itself. Parliamentarians not only cut military budgets but they boasted and bragged about it, including one Pierre Laval. In the name of liberty, conscription was qualified by twenty pages of exemptions and exceptions, while the overall length of service was progressively shortened. A standing, professional army was perceived to be a greater threat to society than a foreign enemy by many ideologues who came to prominence in the Popular Front era of the Third Republic. It is also true that the Communist Party of France, following explicit orders from Moscow, disrupted French defence industries by strikes and sabotage and sheltered those fleeing conscription.

Though French generals said they were ready for war in 1939, despite later denials, the record is clear. It is equally clear that when the German offensive struck they were among the first to show the white flag. To review the last days of the Reynaud government as it fled from Paris, is to conclude that the generals gave up the fight before the politicians did. Prime Minister Reynaud himself was prepared to take the Government into exile and continue the war, as the Dutch, Norwegians, and Danes had done, but the generals, including Pétain advised him to surrender not just the army but the government itself. Reynaud could not bring himself to do that but he bowed to the majority of his cabinet and deferred to Pétain to seek terms of an armistice. Instead Pétain capitulated, precipitating generations of debate about the legitimacy of his initial government.

Later, of course, the generals blamed the politicians, but that is hard to credit. Start with the commander in chief of the field army, Maurice Gamelin, who set up his headquarters in splendid isolation from the front lines in a place chosen more for the wines in its cellar than for its communication or access to the armies he commanded. Read this sentence slowly: After nine (9) months of war, he had in his headquarters no telephone in May 1940.

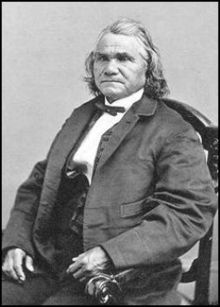

Maurice Gamelin

Maurice Gamelin

He sent and received messages by car and motorbike along country lanes but few roads ran to the border where the army was emplaced. He later explained his inaction in the crisis by saying that he did not know what was happening. Hmm. If communication with Gamelin was slow when nothing was happening, once the front broke he was a hard man to find. (Radio was too easily intercepted for use and unreliable in the heavily forested area and jammed by Germans.)

I referred to doctrines before. Here is another example. The French General Staff had slowly and painfully negotiated an agreement with Belgium before the war to form a line of defence on the Dyle River in Belgium. This Dyle Plan allowed three (3) weeks, 21 days, for the French Army to take its positions along the River Dyle. Care to guess how long it took Germans to breach that line? Three (3) days. Once that happened the French Army had no plan of operations. They had thought of everything except a Plan B. (By the way the British Expeditionary Force was part of this plan and was thus left without a mission.)

Overarching themes:

Officers from general to lieutenants denied the defeat by blaming politicians, British perfidy, spies, lazy conscripts, unpatriotic civilians….women who smoked, protestants, secular education. The list went on. Only the army was blameless for its defeat.

Military contempt for parliamentarians and the Army’s early effort to dominate the Vichy government. Civilian control was only established in April 1942. Apart from Maréchal Pétain himself the Vichy government was dominated in its first crucial months by General Maxime Weygand and then later for longer periods by his navy rival Admiral François Darlan.

Backstabbing, cliques, career opportunism were rife in the very hard circumstance of the armistice army that the conquering Germans permitted. This personal struggle is most well documented at the most senior levels of the army but it was not confined to the top.

Vichy played off Germany against Britain and vice versa by trying to be neutral, not so much in Vichy France itself, but in the colonies, especially those of strategic import like Dakar, Damascus, Djibouti, Diego Surez, Noumea, Oran, and Bizerte. To keep the Germans out of the colonies the Vichy regime defended them from British incursions. To keep the British from occupying a colony there was the spectre of a German response.

There was an effort to use the National Revolution of Vichy to enhance the status of the army after its humiliation. The new curriculum emphasised patriotism and physical fitness and left little time for science. Girls were encouraged to leave school at puberty.

The benign Pétain.

The benign Pétain.

The fate of two million French prisoners of war in Germany preoccupied some officers to the exclusion of everything else and was ignored by many others. These prisoners included all ranks including generals like Giraud, Juin, and others.

Inter-service rivalries that pitted the influence of the army against that of navy, and the navy won very often because it had all those lovely ships which the British wanted and the Germans did not want to Brits to get until November 1942. The army was discredited by its collapse.

The near thoughtless compliance with the purge of Jews from the army, navy, and air force. Likewise the German efforts to identify and seize Germans in the French Foreign Legion is a sorry story of compliance.

Most officers obeyed Vichy because the regime was congenial, not out of duress or desperation. Indeed those officers forcibly retired to reduce the size of the Army clamoured for re-admission.

Vichy officials reluctantly agreed to many German demands but moved slowly to comply. It might take six months to get agreement from them, only to find it was another nine months before they took the first steps. There was a lot of this kind of passive resistance. It is not easy to trace its origin. At times both Pétain and Laval expressed anger at the slow movement of their government, but at other time this pace suited their efforts to keep Germany at the negotiating table.

The Vichy regime presented itself to France and to the world as the sovereign government (of what was left) of France. See, for example, the newsreels at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU61J_xXBAE

(Cut and paste the address into a browser.)

The army’s chain of command held despite the colossal shocks of May and June 1940. By and large the French army from generals to lieutenants accepted Pétain as the government of France and obeyed his orders. But it is important to realise why that chain held despite the unprecedented jerks on it. (It might have been a different story without Pétain. A government with only Pierre Laval at the top, well that certainly would have been less compelling to most officers.)

Officers had responsibilities; they were not free agents. As long as those responsibilities remained and made sense, they stayed at their stations. Paxton makes this point by analysing the officers who joined de Gaulle’s France Libre. They numbered several hundred and then thousands and invariably they were officers who did not have command of men who were dependent on them.

De Gaulle himself is an example. He had been relieved of his field command in May and appointed an under-secretary for war in the Reynaud cabinet, and then sent back and forth to London several times to gouge greater effort from Britain.

The officers who first joined de Gaulle fell into these categories: retired, on unattached duties (ill or convalescing), attachés at embassies around the world (particularly Latin America), staff officers who did not command subordinates, on special assignments (e.g., as couriers, liaison, or missions abroad). These officers were free(r) agents than those with dependents, i.e., subordinates. They came from metropolitan France but also from the colonial forces. Of course they may have had families to think about, too.

While nearly all officers at French embassies in the the Americas saluted de Gaulle’s flag, not every retired or convalescing officer did. The second criterion that Paxton suggests was decisive is access. Retired or unattached officers who had only to travel a short distance to join de Gaulle, were more likely to do so. Many officers on special assignments were already embedded with British forces as liaison or couriers along with scores of others in the United States and Canada on a variety of missions. Some colonial officers had only to walk across the street to a British consulate to get passage to London. But retired or convalescent officers in Lyons or Metz had no such access and so joining de Gaulle may well have never crossed their minds. Later the fear of reprisals against one’s family in France held some officers in check. Others adopted noms de guerre to avoid such reprisals.

In time as the Vichy regime lost creditability. The unopposed Japanese seizure of Indochina shocked officers far and wide but most of all in Indochina, from which some intrepid souls found a way to abscond and travel, slowly, to England. German setbacks like the stalemate at Stalingrad encouraged others to abandon Vichy neutrality for the opportunity to return to the war effort, e.g., those garrisons in India (a surprising large number). While some officers were staunch themselves they turned a blind eye to the departure of junior officers, forging roll calls to fool German supervisors. Yes, there were German supervisors throughout the French colonial Armistice Army, as well as the Armistice Army in Vichy territory.

Officers in the Armistice Army in Vichy also acted in secret. Rather than turn over all weapons and ammunition to the Germans, they hid much against the future. One trove, scattered in numerous caves, mines, commercial wine cellars, abandoned barns consisted of thirty-nine (39) tanks! The tanks had been disassembled and crated, marked as agricultural material and salted away.

When American troops landed in Morocco and Algeria in November 1942, the veil fell. The Vichy chain of command was by then muddled. Mistrust, suspicion, fear of reprisals from either Germans or Gaullists, residual anti-German feeling, loyalty to Pétain, inter-service rivalries between the navy and the army, tests of will between civilian control and military, all had grown over time and reached new heights; this brew bubbled, collided, mixed, leaked when reality of an Allied invasion occurred.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

The velvet gloves come off and panzers roll into Vichy France in November 1942.

Contradictory orders were issued one after another by a single commander as information came in or was discredited. Conflicting orders came from civilian and military authorities, who then disputed each other’s right to give orders. Generals disputed the authority of other generals to give orders in the crisis. Messages from Vichy said one thing and the local representative of Vichy said another.

Because communication with Vichy was disrupted, the chain of command was altered, but not everyone got the message about the change. Some commanders got orders from generals they had never heard of. Confusion was the result and that led often to inertia and paralysis. Though the reaction of soldiers when attacked is to reply in kind, there was no decisive leadership and the will to resist dissipated within hours. The soup of conflicting orders, contradictory orders, the unabated undermining of rivals confused the matter all the more.

One example is a captain with a company on the beaches at Casablanca received orders from a his colonel to greet the arriving Americans as allies, and almost simultaneously orders from his major to fire on the landing parties. Faced with this contradiction, the captain took his men back to the barracks. The colonel and major were each passing on orders they had received.

In this mire, the castle was Algiers where the headquarters of the French colonial forces in North Africa was located. The conflict and contradictions were played out there with full force. In addition the American sponsored alternative to de Gaulle, Henri Giraud arrived with his immense prestige as a soldier and his childish incomprehension of the political situation, along with the American commander General Mark Clark whose campaign had already fallen behind schedule. In addition, François Darlan, Vichy Minister of Defence and commander in chief of the French navy was in Algiers on private visit to his ill son. The clash of these egos was seismic. The French would not agree among themselves, still less with Clark, but he had the bayonets.

At stake in this opera in Algiers was nearby Tunisia. It was the frontier between Vichy North Africa (and now the Allies) and Rommel’s Afrika Corps in Libya. The Germans wanted to use Bizerte as a port to supply Rommel. Vichy neutrality forbade that. When it became clear that the Allies had taken over in Algiers, and when de Gaulle arrived there and ended the fruitless negotiations with Vichy officials, the Germans stopped asking and started taking. In response the French troops in Tunisia turned on the Germans. As soon as this switch was reported by the Germans to Vichy, Pétain relieved the Tunisian commander, General Alphonse Juin, who ignored the order on the assumption that Pétain’s hand was forced by Germans. The chain of command snapped at long last.

Now the Armistice gloves were off from Morocco to Tunisia and Djibouti, and French officers along with their commands in these stations joined the Allies as speedily as possible. Within a few months every French colony was aligned with France Libre. Thereafter, General Juin’s 100,000+ man First French Army led the way in the Allies’ Italian campaign. At the bitter end, Free France had 250,000 soldiers in the field in Europe.

The necessities of war brought Great Britain and Vichy into conflict to be sure. While Hitler had promised not to seize the French fleet, he was not a man famous for keeping promises. While French admirals swore not to let their ships go, would they be able to resist at the moment of truth or would they, like so many others, be overwhelmed by the Nazis?

Noteworthy, but not mentioned is that the Armistice Army was never used to enforce order in any sense. This army did not round up Jews. It did not kick in doors to arrest trade unionist. Its parades were not designed or intended to intimidate onlookers, in contrast to German parades in France. Rather these parades were intended to boast morale in the ranks and in the viewers.

I do wish the author had included some kind of chronology of major events with a comment on the fallout of each as I did above.

I do wish the author had included more numerical information, i.e., data about the military formations discussed. Numbers are mentioned at times, but a table or graph would be more effective.

I do wish the author had more systematically distinguished the metropolitan Armistice army from the colonial Armistice army, and then offered some general account, complete with tables, of their size and distribution.

Only a few sentence end with conjunctions in this book, however. This regrettable tendency is much in evidence in another Paxton’s books.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘Pierre Laval and the Eclipse of France, 1931-1945: A Political biography’ (1968) by Geoffrey Warner

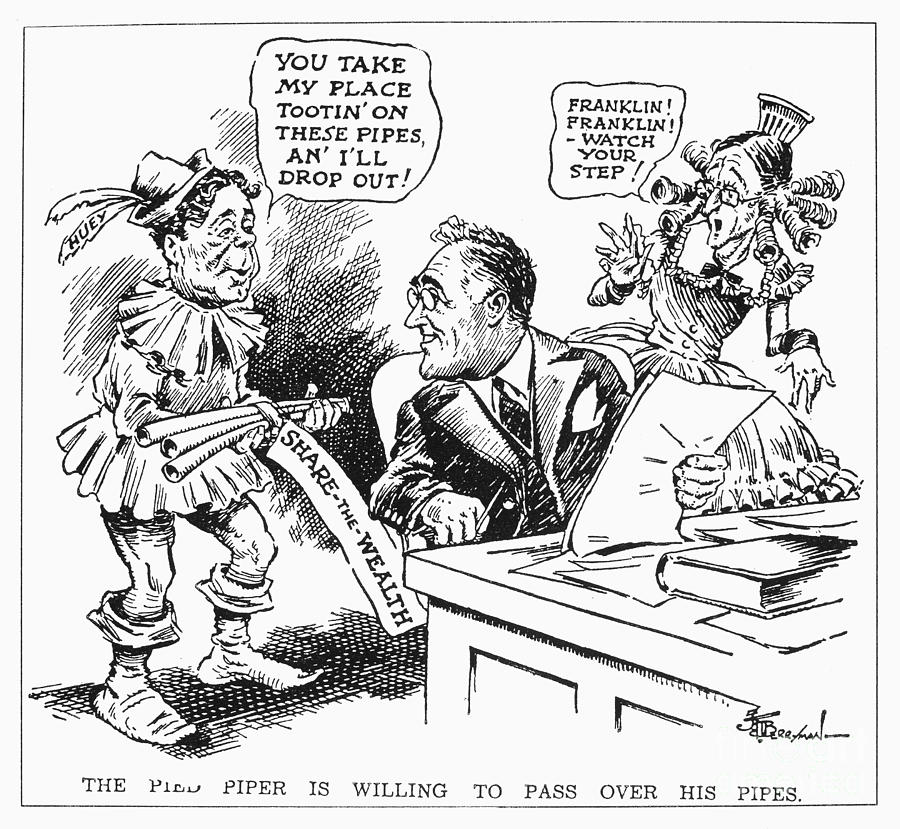

Laval was the dark prince of the Vichy Regime (1940-1944).

Pierre Laval in 1931

Formally, he was prime minister while the venerable and elderly General Phillipe Pétain was president. These two hated each other and spent a good deal of effort in undermining one another. Although Pétain was willing to collaborate with the Germans and re-make France into an agricultural nation bound to family and church and reject the Third Republic and end all that liberty, equality, and fraternity rhetoric in favour of work, family, and country, he did draw lines against the Germans. Not so Laval who gave in to German demands at every turn, and at times offered more than the German demanded. He said that he did it to secure the good will of the occupier. There was never any evidence that good will resulted. When the Germans demanded slave labor, disarming the fleet, handing over Jews, Laval complied. Pétain did not.

Laval had entered the national assembly as a Socialist, having had a career as a labor lawyer. There he formed a boundless ambition, and a belief in himself that became delusional. In pursuit of that ambition he moved across the political spectrum to the centre and then the right. In the Third Republic in the 1930s he was a foreign minister, interior minister, and prime minister at one time or another.

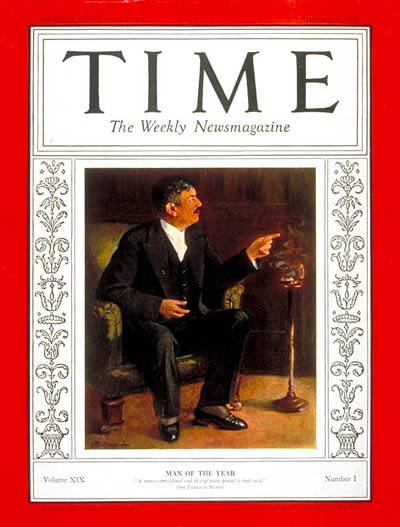

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

Time’s Man of the Year in 1932

In each case he was convinced that he alone could save France from external enemies (Germany) and internal ones (Communists).

In this biography he seems not to have been a reflective or introspective person. Self-doubts, he had none.

I said ‘delusional’ above. To explain, while prime minister he hoped to befriend Mussolini’s Italy and use it to restrain and buffer Hitler. At the time he started on this policy it had some promise. But to everyone but Laval it soon became apparent (1) that he had no influence with anyone in Italy and (2) that Italy followed and did not lead Germany.

No evidence convinced him to change his course. One rebuff after another from Rome, was dismissed as a bargaining ploy, an effort to conceal his influence from Hitler. In the effort to stop Laval’s endless messages to Rome, the Italian foreign minister wrote a letter, couched in very undiplomatic terms, to tell him to stop and sent it to the French foreign minister of the day who read it in parliament in an effort to silence and embarrass Laval. It did not slow him down a beat.

Later he developed a similar fixation on his capacity to influence Hitler, and repeated rebuffs did not faze him. He had a number of interviews with Hitler, and got virtually nothing from them, but that only led him to try harder to get another meeting where he would surely score a great coup.

One of many meetings

One of many meetings

How others saw him

How others saw him

Nor were his delusions limited to foreign relations. His start as a socialist gave him the abiding belief that he (alone) could unite the social divisions of France. Each failure to do so, he took as a sign that he was succeeding little by little.

One can only admire his tenacity and optimism while deploring his grasp of facts.

Maréchel Pétain was 84 when the Vichy government took form. While the Germans and the French were glad to have such a respected figure associated with the papier-mâché regime, they also considered that he might die at any moment. Anticipation of what might happen if he died, set off one palace intrigue after another as members of the Vichy government manoeuvred to have themselves named as his inheritor. Laval was the most conspicuous schemer but he was certainly not the only one.

By December 1940 Laval had irritated most other members of the six-month old government since its inception in July of that year. He was always a fast worker. In order to secure German good will he had cut across the domains of other ministers and given away French assets for a hand shake, and sometimes not even that. Accordingly, six of the eight other minister convinced Pétain to dismiss him. Pétain did not take much convincing.

It was done with a combination of subtlety and force. It was a ritual of Third Republic governments for ministers to sign a collective letter of resignation which the head of state (Pétain in this case) could use to drop an unpopular minister and placate public option or the parliamentary parties. At a routine 8 pm cabinet meeting one such letter went around the table and each minister signed it. The unspoken assumption, at least in Laval’s mind, was that it would be used to drop a junior minister who was ill and not at the meeting. As per the ritual, when the letter got to Pétain there was a short break and he retired to another room while the others drank coffee and smoked. He came back ten minutes later and said the ‘resignation of M. Laval has been accepted.’ The explosion went off!

Laval, completely taken by surprise, shouted, thumped the table, and nearly cried. To Pétain who had stood down generals under fire this reaction was most unseemly. Laval was bundled out of the room by other ministers and taken into custody by the Praetorian Guard (Pétain’s body guards) and put under house arrest some miles away. Although Pétain had told the Germans a few hours before he was making a change of government, they, too, were surprised and demanded Laval’s immediate re-instatement. Pétain refused. After 72 hours of pistol waving, angry telegrams from Berlin, a new prime minister (who was acceptable to Berlin) was named, and the Germans took Laval to Paris for the next 16 months.

Note that it was in Paris that the real extremists congregated and not in Vichy. The French fascists, the anti-semites, the New Europeanists (code for the German Europe), published newspapers, pamphlets, and books in Paris damning the Vichy government for its sloth, weakness, and lack of enthusiasm for the opportunity to cleanse France. They produced anti-semitic films and curated anti-semitic exhibitions. Applied their creative powers to anti-British propaganda which convinced themselves, if no one else, that Great Britain was the real enemy. They held rallies and attacked all manner of people in the street to show how tough they were. A few (very few) who really believed what they said volunteered for service on the Russian front. Laval was never quite comfortable with these zealots; he was — I think — an opportunist in service of his ambition and not an ideologue.

During this interregnum the Germans kept Laval on tap in Paris as a threat to the Vichy regime. If it did not comply with German requests, the Germans retained the option of creating a new French government in Paris with Laval at the head. Remember that by now Pétain was 86 and he might die at any moment. If he did can anyone doubt, they reasoned in Vichy, that the Germans would crown Laval? For his part Laval toadied, conspired, lobbied, and generally tried to ingratiate himself with German authorities.

Absent Laval, the scheming and musical chairs in the Vichy regime continued. Prime Ministers came and went, each trying to get Pétain to pass the mantle onto him. Ministers and ministries changed monthly or so it seemed. Until November 1942 Vichy did exercise administrative responsibilities of many kinds but once the Allies landed in North Africa that ended. Yet the Germans continued the mirage of Vichy as a means of stability. At the insistence of the Germans Laval returned to Vichy and to government after 16 months of his Paris exile and exacted his revenge on everyone, though Pétain himself and his immediate entourage was untouchable, not so others who were soon deprived of position, income, accommodation, and even papers. The Germans perceived Laval as the most pro-German of the Vichy figures and they also wanted at least the veneer of continuity in the Vichy regime.

Laval, that master of self-delusion, continued to suppose the Germans would win the war and said so often. That had been plausible in August 1940 but it no longer was in August 1944. No evidence could ever dent the Maginot line of his delusions. Throughout 1943 Laval conceded nearly every German demand. Indeed, he only declined in cases where he did not have the capacity to deliver.

Oddly enough as the Vichy regime withered and shrunk in early 1944 there was a clamour from the Parisienne ultras to join the government, and Laval finally agreed, over Pétain’s objections. As the ship was sinking, more rats got on it.

In August 1944 with American, British, and Free French armies a few miles from Paris, the Germans, perhaps out of the same strange loyalty that led to the German rescue of Benito Mussolini, moved Pétain and Laval and few others to a castle on the Danube. Laval had fled to Spain but the Spanish surrendered him to the French provisional government which tried and executed him in short order. Initially Laval seemed to think he was going home to a hero’s welcome.

At this trial he lied as freely, as he had done throughout his career, and when presented the evidence of a lie, he shrugged and went on.

There is no doubt that in the end Laval believed he had done France a great service by buffering the Germans. Like Socrates, he nearly suggested that he be rewarded rather than condemned. The author refutes this claim with some comparisons to other occupied countries like the Netherlands and Belgium who governments went into exile.

His trial was no model of justice, but the author contends that there was and is no doubt that Laval was guilty of treason, however defined, but certainly within the meaning of the relevant French law. A lot more guilty than, say, Alfred Dreyfus or Léon Blum who had been tried on this charge in trials that were not models of justice either. Nor can one deny the conclusion that Laval was also a scapegoat for a lot of other people who trucked with the Nazis.

The book is definitive. It is based on primary sources from French and German archives, both civilian and military, with other material from the United States, which (too) long maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy regime. It is measured and the prose clear, letting the story speak for itself and letting the reader draw conclusions.

Simone de Beauvoir, who is not mentioned in the book, covered Laval’s trial for a newspaper, and remarked that as much as she hated him, and hate him she did, the Laval that was on trial was not, or did not seem to be, the man she hated. He was diminished, small, uncertain, cowed, not the brash, bull-headed know-it-all man, who crashed through and crushed all in his path. Some of that diminution is physical. Laval’s table had always been sumptuous in Vichy, even when the rest of France starved, but after August 1944 he lived on German army rations and then prison food. He lost weight and colour from his complexion, the hair greyed. His one suit of clothes wore through. Then there is the fact of being on trial for his life…the round shoulders and bowed head. His was no longer the whip-hand. Her essay is reprinted in her ‘Ethics of Ambiguity’ (1962).

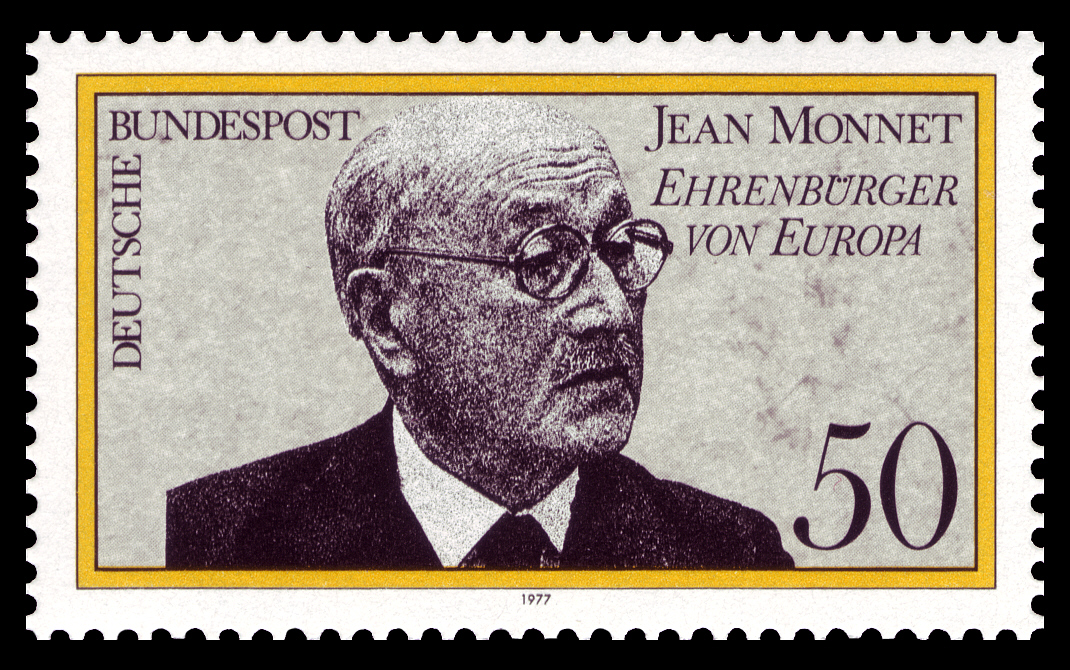

‘Jean Monnet: Unconventional Statesman’ (2011) by Sherrill Brown WELLS

‘Jean?’ who you ask. Jean Monnet (1888-1979). He ought to be called ‘The First European,’ since he is widely regarded as the mid-wife of the European Community. Quite an achievement for someone who never held an elected office and who was never a civil servant. Yet by wit, tenacity, wisdom, patience, a vision, an appetite for data and facts, a network of friends and acquaintances all over the world, he kept moving toward a European union, and he got a lot of other people to move in that direction, too, including Charles de Gaulle.

In 1938 the French Prime Minister sent him on a special diplomatic mission to the Washington D.C. In 1940 Churchill gave him a British passport and sent him on a special diplomatic mission. In 1943 Roosevelt entrusted him to be his representative in Algiers.

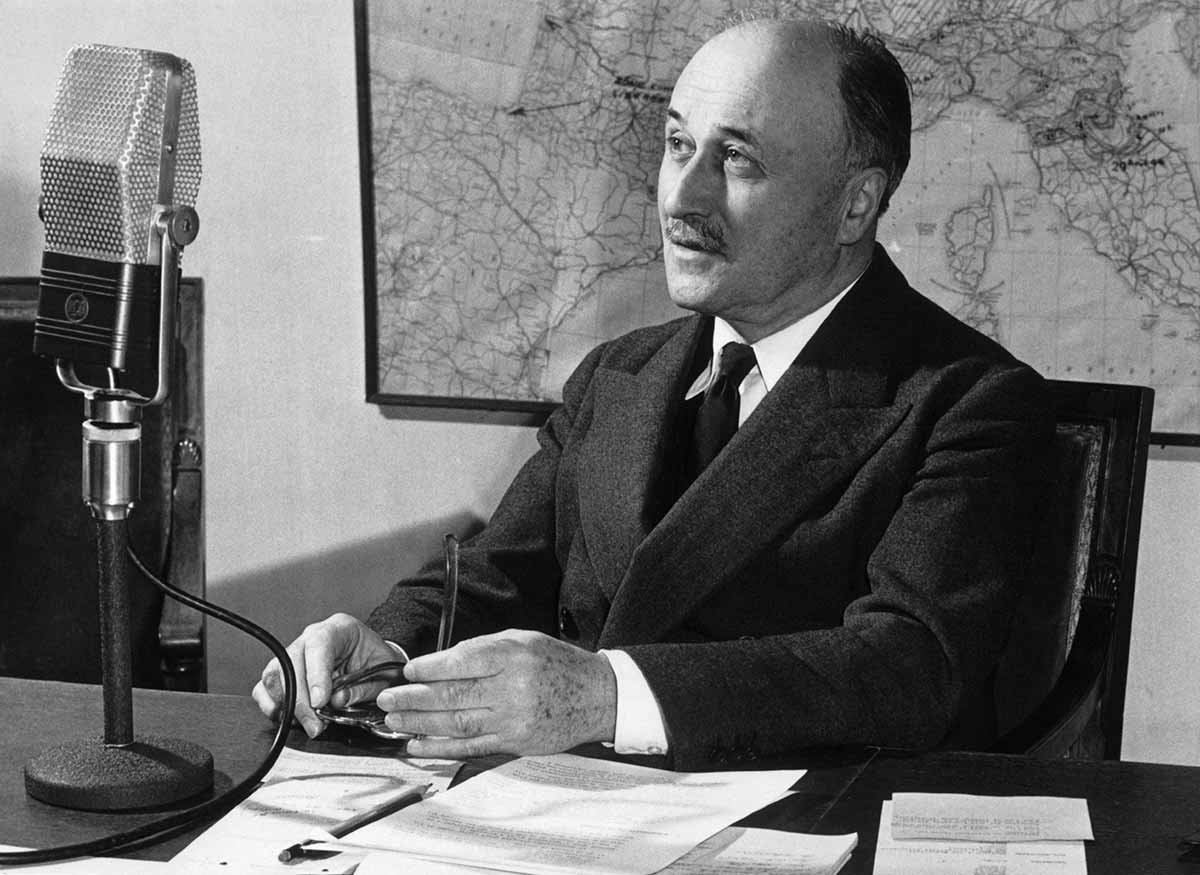

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Monnet in Algiers in 1943

Internationalist indeed. This was just the beginning.

In Monnet’s mind European union was the means to the bring of enduring peace to Europe. He was born into a wine family in the Cognac and began working for the family company at 16. At that age he learned enough German to sell barrels of brandy to German buyers. Later as his father innovated and expanded the business, he sent young Jean to London to learn English while selling brandy. There he found his best single customer to be the Hudson’s Bay Company of Canada which bought in volume for national distribution. In time the Bay hired him, with his father’s encouragement, and he spent time in Canada, and from there the United States.

Asthma kept him out of the army in World War I, but, inspired by his experience with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he proposed to the French government that it join with Britain in a consortium to purchase not just war materiel but everything else, too, including the shipping to transport it, and the bank loans to pay for it all. An Inter-Allied Committee evolved out of this suggestion and Monnet was its executive assistant, and in no time at all he ran it in everything but name. There were many conflicts on this committee and Monnet was the one who never gave up, who stroked egos, who broke the conflicts down into a small pieces to find common ground, who developed the spreadsheets to demonstrate the priorities…. This committee was successful beyond anyone’s expectations. By the way, it was a small committee of four (USA, England, France, and Italy) and that was another enduring lesson. Keep executive committees small.

Toward the end of the war he left that committee and worked for Herbert Hoover in war relief for Belgium and France in that Herculean effort where twenty hour days were the norm.

At the end of World War I he went to work at the League of Nations, serving there for three years as an international public servant. He passes through Frank Moorhouse’s superb novel ‘Grand Days’ set in the League.

Lured by the business opportunities offered by friends in the United States he moved there and made millions of dollars only to lose it all, as did so many others, in the Great Depression. He went from multi-millionaire to pauper in a few weeks. His passage back to France was paid by friends, including John Foster Dulles.

Never one to sit idle, back in France he received an offer from Chiang Kai-shek’s government in

China to set up and import-export bank in Shanghai. One of his League of Nations colleagues had recommended him for the job. He took it and succeeded, where several others had already failed. Later a dynastic power play in Madam Chiang’s family pushed his patron out of the bank and Monnet with him. His greatest achievement in this venture had been to convince the Chiang government that it had to re-pay all outstanding debts before trying to borrow more. This was a hard sell and it took a couple of years. He also made quite a profit from the three years he spent there.

He married an Italian woman who had left her husband. No divorce was possible in Catholic Europe. Both Monnet and his wife-to-be became Soviet citizens because divorce and re-marriage there was easy. She travelled from Switzerland to Moscow and he from Shanghai and there she divorced her husband and married Monnet. Reds! How did he live that down in the Cold War? This book sheds no light on that.

When he returned to Europe Monnet hatched a plan for France to buy airplanes from Canada. These airplanes would be assembled in Montréal from airframes and engines manufactured in the United States, in a work-around of its policy of neutrality. In the course of devising this plan Monnet had private meetings with President Roosevelt at Hyde Park.

The French capitulation occurred before those planes were delivered, 5000 in all, but Monnet on his own responsibility signed them over to Great Britain. For this act, and many later ones, the Vichy French regime charged him as a traitor. De Gaulle did the same, by the way, with military equipment intended for the French army in 1940: Gave it to Britain.

Churchill’s desperate gesture to keep France in the war in May 1940 after Dunkirk was to create a union government combining France and Great Britain as one. Churchill offered to defer to Paul Reynaud as the head of such a government. Quel beau geste! In London Monnet wrote the text for Churchill. The idea was that then Reynaud could take the government out of France to London and the French fleet and France’s considerable colonial army could be brought into the war. Reynaud could not convince his cabinet to continue the struggle and the moment passed.

Though Monnet supported de Gaulle’s effort to keep France in the war, he feared basing it in London would compromise it in the eyes of Frenchmen, which it did. He tried to convince de Gaulle to move to Algiers, and so remain on French soil. De Gaulle did not, and probably wisely. To move Free France to Algeria in 1940 or even 1941 might have meant capture by Vichy. Moreover, even if Algiers could be won over, location there would mean foregoing the material support Great Britain offered in London.

In 1943 Monnet was thinking ahead about European reconstruction. In Washington he used his business and political contacts to talk incessantly about the necessity of economic reconstruction to ensure social stability, including one lunch at the Pentagon with George Marshall. Monnet was responsible for American Lend-Lease supplies going to Free France. In fact, at the times he was the de facto American administrator of Lend-Lease going to Free France, and the de jure French manager of the supplies obtained. In this role he was a tyrant for propriety, insuring there was no hint of the graft, corruption, or profiteering that marked so many Lend-Lease operations elsewhere. This propriety made later Marshall Plan funding easier to justify.

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

Explaining the Coal and Steel treaty

The historic conflicts between France and Germany, in the industrial age, had focussed on the Saar, Ruhr, Pas de Calais, Alsace, and Lorraine because there is where the coal and steel was. In 1943 Monnet was drafting plans to internationalise these regions under joint control of three or four countries. This is the seed of the European Coal and Steel Community, which later gave birth to the European Community. Monnet’s idea was to take the means of modern war out of the hands of a single country to put them into some kind of transparent international protectorate.

He was the author of the Schumann Plan that embodied this ambition and led to ever greater French and German collaboration and European unity. It was not easy going, and it took nine complete versions to get a plan that both France and Germany accepted since it involved a diminution of sovereignty. While others gave up and quit, Monnet persevered. The European Coal and Steel Community became the first voluntary European entity since the Holy Roman Empire. I omit the League of Nations because of its origins in Woodrow Wilson’s insistence on it as the price for the Treaty of Versailles to end World War I.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

With Robert Schumann, foreign minister, selling the big idea.

No sooner was the ink dry on the Treaty of Rome in 1957 which marked the beginning of the European Common Market, European Community, European Union of today, than Monnet began to talk about financial integration. He set up an Action Committee of private citizens, partly funded by foundation (including Ford and Rockefeller) grants, to organise seminars, radio lectures, publish discussion papers on financial integration, brief journalists which in time came to be a common currency, the Euro.

As successful as he was, Monnet had failures. Try though he might, he could not convince Roosevelt to recognise de Gaulle’s Free France as the provisional government of France in 1943.

Monnet also proposed a European army, partly motivated by the Soviet Union’s machinations at the time of the Korean War. This, too, failed. His aim was to contain German re-armament within such a pan-European army.

Another failure was Euratom which he proposed to make nuclear research European and so not put to military use by a single nation. France itself would not agree to this limitation, though the initiative is in the genealogy of CERN in Geneva today.

How did Monnet do all of this? Most of all he was a salesman. He loved big ideas and no idea was too big to interest him. He did not think of reasons why a big idea was impossible. As he emerges in this book, he is not reflective, nor introspective, and certainly not given to self-doubts. The harder the sell the more energised he seems to have been. He was not a writer either. The many policy proposals and discussion papers were terse, and detailed in dot points, graphs, tables, maps, and charts. The text would be filled out later by others. His preferred method of exposition was discussion and he was a master of that whether in a seminar, at the podium, dinner table, or a seat on a train or plane. Every occasion was used to develop, test, and advance the big ideas.

How did he live? Often he was sustained by the grace and favour of friends and admirers. He had no fortune and long ago he had signed over his share of the family business to his brothers. The money he made in China was considerable but moving in the elite circles he did meant the best restaurants, the best hotels, first class passage on ships and planes. He exhausted that money soon enough. His service on one special mission after another, yielded living allowances and nothing more. When at 70 he slowed down, to live on …. a pension derived from his three years at the European Coal and Steel Commission and that is all. He agreed to write memoirs in return for a hefty advance which supported his last years.

His name is everywhere in Europe. On postage stamps, commerative medals, universities, think tanks, government fellowships, busts and plaques in foyers of EU buildings in Geneva, Brussels, and Strasbourg, and the like, and yet he remains largely unknown, ever the stage manager in the back while the stars tread the boards before the audience of history. Indeed his name can also be found in Australian universities and yet few could say more than a sentence about him.

Monnet cognac remains in the market though no member of the family is now associated with it.

The book is comprehensive and thorough with admirable documentation. It is far more interesting than the first biography of Monnet I tried to read. Perhaps because Monnet was not a leader and did not hold an office, there seems to be little drama or momentum in the book. To confess, as fascinating as the story is, I found it a test of will to finish reading it.

Aside: Roosevelt’s handing of all things French in the war seems to have been clumsy and ill-informed for such a master juggler. Roosevelt overrode his Secretary of State to maintain diplomatic relations with Vichy from July 1940 to November 1942. Roosevelt’s hand picked ambassador to Vichy recommended suspending diplomatic relations but FDR ignored this advice. Did Roosevelt hope that indulging Vichy would make things easier when the landings in Morocco occurred? It did not. Vichy ordered resistance and resistance there was. Ditto in Algeria. In Algeria the United States through diplomat Robert Murphy indulged the Vichy governor Admiral Darlan and tried to undermine de Gaulle. Darlan enforced Vichy’s anti-Semitic laws, arrested and deported to France enemies of Vichy, transported Jews to France for German death camps, and more while America officials and officers looked on. Even though by that time it was clear Vichy would not, could not open any doors to France when the invasion came to the continent.

‘Flykiller’ (2002) by J. Robert Janes

A krimie set in the heart of Vichy administration in February 1943, a bitter winter in a France without coal, food, oil, wool, or much else. Having just read Robert Paxton’s study ‘Vichy France 1940-1944’ I thought to re-read this title which features some of the historical characters mixed with imagination.

This is the an entry in a long running series featuring Jean-Louis St-Cyr of the Sûreté Nationale and Hermann Köhler of the Geheime Staatspolizei, Gestapo. This odd couple are assigned the most sensitive investigations by either German Occupation or Vichy authorities throughout France after the Defeat (16 June 1940).

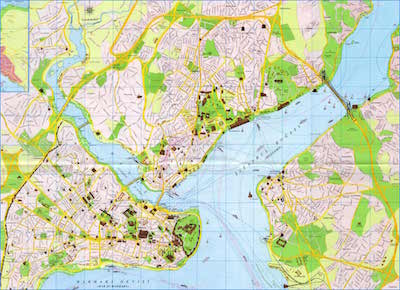

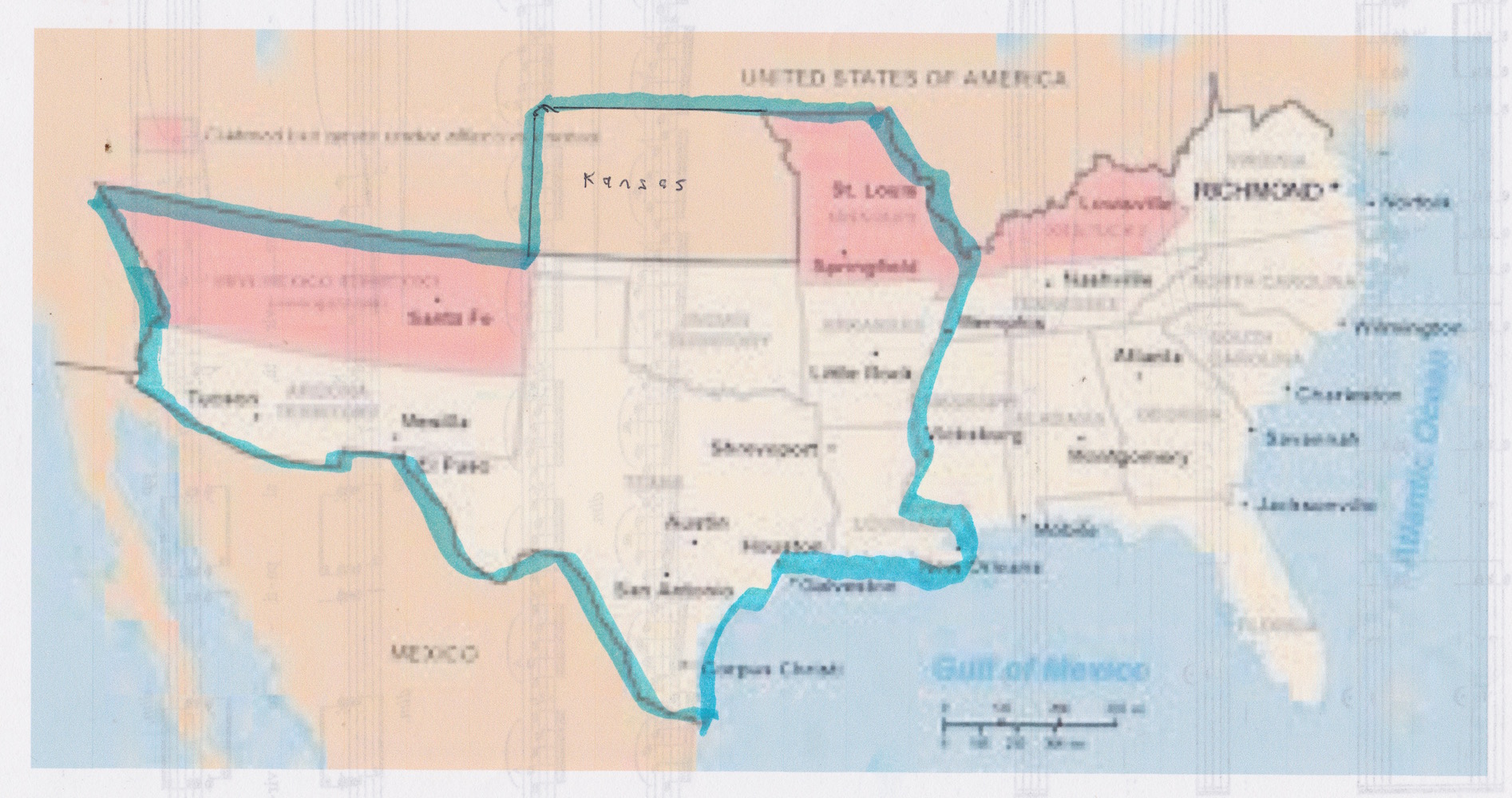

It was a France dismembered and divided. Germany annexed Alsace and made Lorraine a special administrative unit an inch short of annexation. The coal and steel producing Nord around Lille was administered from Brussels by Germans. Italians occupied Nice, Corsica, and the Savoy. Finally there was Zone Occupée, the north and west coasts defined as operational areas. Each one of these divisions and dismemberments produced a boundary with checkpoints and rules of exclusion.

That occupation broke the chain of command that had held previously in nearly all of its far-flung colonies and throughout much of the French armed forces, but when the Germans disarmed and dismissed Vichy’s Armistice Army in November 1942, the chain of command broke for military men, too. Many of them now felt free to follow their personal convictions and joined France Libre, especially those in North Africa who had ready access.

To illustrate the internal border controls mentioned above, only 250 letters a day were allowed to pass from the Zone Libre (Vichy) to the Zone Occupée. That is a post of 250 between 40 million people! So strictly was the border between Vichy and Occupied France imposed that even Maréchel Pétain was not permitted to cross it to enter Paris for years. No mail at all was allowed to some amputated parts like Alsace.

By February 1943 the Vichy Regime no longer had a purpose, at least not a French purpose. The Germans continued the fiction because even this hand-puppet government retained enough legitimacy to keep some of the population quiet.

The Vichy establishment had until that November been a Ruritania amid the luxury hotels, the Majestic, Palais, Grand, Prince, and d’Enghien. School desks were set up in the hallways for clerks. Ministerial offices were in suites. Down stairs the thugs from the Garde Mobile provided security, many of them released from pre-war penal sentences.

Prime Minister Laval, the dark prince of Vichy, and President Phillipe Pétain, the figurehead, hated one another. Laval thought Pétain a relic, paralysed by the past, and more interested in breakfast than high politics. Pétain called Laval a peasant, one who blew cigar smoke in his face time and again, preferring as prime minister the austere Darlan or toadying Flandin. Pétain and Laval each plotted the other’s downfall. Laval had traversed the Third Republic, from a Socialist, to a Radical, had been foreign minister, had been prime minister, and came from the Auvergne (Vichy) where he owned a newspaper and radio station. Laval’s powers of self-delusion were so great that he continued to believe in the final victory of German even late in 1944 when most of France had been liberated by the Allies.

It is this same Laval who asks for the service of St-Cyr and Köhler when a young woman is found stabbed to death in the foyer of the long-closed Hall des Sources, the hot springs. This sybarite kingdom was closed in June 1940 and stayed closed since. When St-Cy and Köhler arrive, at 2 a.m., having been summoned from elsewhere, the heat has been off in the Hall for two years and it is freezing outside, yet the hot springs beneath impart warmth to parts of the building, steam vents from pipes broken and not repaired, wherein there is no electricity. As they move about with lanterns, the building seems to breath and even move when images are reflected in the many mirrors , frosted windows, and dull but polished surfaces. Very nicely done.

One such spa

One such spa

St-Cyr has an empathy that allows him nearly to communicate with the dead. He studies the corpse, ear rings, clothing, shoes, feet, hands trying to infer the events the that brought the victim through the snow outside to her death in the locked and abandoned building. Köhler takes a more empirical approach, looking for a lost earring, a boot mark on the base of a counter, recent chip in a beveled edge. The two detectives combine the metaphysical and physical worlds.

Each man served in World War I at Verdun where each was wounded. Both now in the 50s both are too old for military service. Each has been a policing since 1919, and they first met at a police congress in Vienna twenty plus years before. When Köhler was made a one-man flying squad for France, he asked for a French offsider and asked for St-Cyr by name. St-Cyr learned German with his Alsatian relatives, while Köhler learned French in a prisoner of war camp.

Köhler is not a loyal Nazi, still less now that both his sons were killed on the Russian front and his wife left him in the aftermath. St-Cyr sees in Vichy elite many of the embezzlers, opportunists, thugs, and chancers he used to jail. That he works with the Germans, makes him a collabo to many Frenchmen. His wife and child were killed in a bomb blast perhaps meant for him by one of the many factions of the Resistance. ‘Collabo’ is collaborator.

The most venomous French collaborators were the intellectuals in Paris, not the officials and bureaucrats in Vichy, apart from the very top ranks. The collabo Parisienne intellectuals, journalists, academics poured venom on Vichy for its trepidation, its hesitations, its half-hearted pursuit of Jews, its failure to seek out spies in its midst, and so on and on. No exaggeration was enough. No cause too trivial to unleash a torrent of bile. Whoops! Starting to sound like Fox News or The Australian newspaper.

What does the title ‘Flykiller’ mean? Good question! Go to the head of the class. That very question is asked in the book, but not answered. ‘Tue-mouches’ is a code name used by Prime Minister Pierre Laval. In an end note it seems ‘Tue-mouches’ was the code name for Jean Schellnenberger, arrested, tortured, and shot by the Milice in Dijon in 1942.

It is a complicated story with wheels within wheels and more, but finally satisfying. Many blue herrings are followed. A gallery of innocent and guilty ones are reviewed to find the culprit, the Flykiller. The period and place details is credible as is the language. But having said that Jane taxes the reader a lot by seldom clearly signaling who is speaking. Worse since much is thought and not said, in this time when words killed, it is sometimes not clear whose thoughts are on the page. I do wish he learned it write ‘St-Cyr thought’ or ‘Hermann said.’ It would speed my reading and comprehension.

J. Robert Janes

There are a dozen more titles in the series.

Warning! Tangent ahead:

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s (1907-1977) film ‘Le Corbeau’ (1942) is a subtle critique of life in Vichy France made for the German film company Continental in France, and passed by both the German and Vichy censors for national distribution.

Lobby card when the film was re-discovered

Lobby card when the film was re-discovered

The ironies of life are these. In the early 1930s Clouzot worked in Germany for Continental making French version of German films. He was dismissed because he mixed with Jews and spoke against their exclusion from the film industry. He went back to France where he found getting work hard because he was perceived to be a friend of Germany. During the Occupation he found work again with the French branch of Continental making ‘Le Corbeau’ which caused him to be banned from film work from 1945-1947 because the film vilified the French. Upon release the film had been denounced by Vichy reviewers, by reviewers in Resistance newspapers, and by German reviewers, who had it withdrawn.

Henri-Georges Clouzot

He managed to offend everyone in this simple story. Doh! Clouzot’s had tuberculous and, perhaps, had not the strength to explain or defend himself, nor perhaps the inclination. When the ban was lifted he made some memorable films like ‘Quai des Orfèvres’ (1947), ‘Le salaire de peur’ (1953), ‘Les Diaboliques’ (1955). and ‘La Vérité (1960). None of these films fits neatly into a category and so he again irritated reviewers one and all. ‘Quai des Orfèvres’ is a police procedural which is also a study of life in a broken and impoverished France. It does not glorify the police officer nor condemn the villains but treats each as a fact of nature like a thunderstorm. ‘Le salaire de peur’ is an exposition of the nihilism of existential philosophy at a time when most film reviewers were in love with it. ‘Les Diaboliques’, well, these were liberated women without the rhetoric. ‘La Vérité’ is a critique of social hypocrisy among the very people who attend such films. Then there was ‘L’Enfer’, unfinished, a study of obsession though there is a documentary film about it called ‘Henri-Georges Clouzot’s “l’Enfer.”‘ Another Vichy film is ‘L’assassin habit au 21’ (1942) which reduces Vichy to a single rooming house in which one resident is a murderer but which one? It is played as a parody of the murder mystery and so was passed by censors but it irritated reviewers for its failure to conform to stereotypes.

Robert O. Paxton, ‘Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944’ (2001 [1971] )

A wall poster of General Pétain features in the opening sequence of ‘Casablanca’ (1942) and that film concludes with a bottle of Vichy water tossed into the rubbish bin. That’s about all I knew about Vichy France.

Pétain was 84

Pétain was 84

Whereas every other country Nazi Germany conquered was placed under direct German rule, France was not. The Vichy Regime, as it became known, by the terms of the Armistice was to govern all of France, even though the North was occupied by Germany. The Occupation was only military. Civilian life was the domain of the French government, temporarily located in Vichy.

Divided and dismembered France

Divided and dismembered France

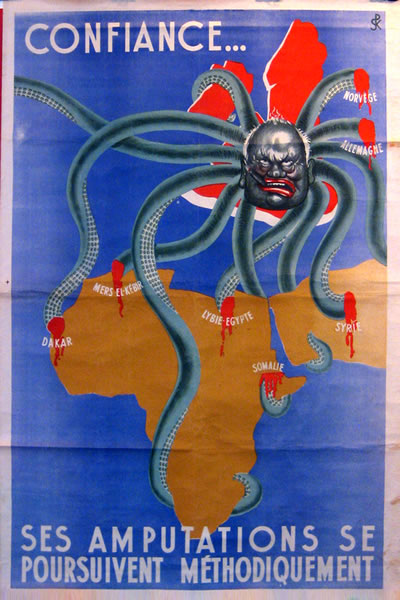

Among the overarching themes in the book are these: First, Vichy evolved as the war developed. It transformed itself, in part, and was later transformed by the Germans. Second, at the start Vichy earnestly sought co-operation with Germany, to which Germany was indifferent for a couple of years, until the tide of the war changed the calculus. Third, Vichy had nominal responsibility for the whole of France, i.e., including the Occupied Zone in the North and West for schools, hospitals, police, roads, and so on. Fourth, in practice France was divided into three not two zones, the third being Paris itself where the German presence was the greatest and collaboration was the most blatant. Fifth, the Vichy regime was internally riven by ideology, religion, region, and personality, united only by an abhorrence of the Third Republic and a willingness to work in Vichy. Sixth, Vichy’s commitment to retaining the Empire ran deep, hence the undeclared naval warfare with Britain, the defence of Syria and Algeria, and Vichy bombing attacks on Gibraltar. Vichy propaganda supposed Britain’s only war aim was to seize the French Empire. In this context Vichy propaganda portrayed General de Gaulle as a puppet for Britain to steal the French Empire away, which partly explains his intransigence in trying to retain every foot of the French Empire from Syria to Morocco.

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

That is Churchill as the head of the octopus

Germany wanted France out of the war, and did not want a French government-in-exile to continue the war in any way. Why not? After all the Norwegian, Dutch, Polish, Belgian, and Luxembourg governments-in-exile existed and were of little moment.

France was different because (1) of its proximity to Britain for the putative invasion, (2) its size compared to these others, (3) its navy which was second only that Britain, and (4) its colonial empire, particularly in North Africa – Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and the Levant. A united French government-in-exile might make a very large difference in one or all of these dimensions.

As to (1), in July 1940 the German plan was to concentrate on an invasion Britain as soon as air supremacy over the Channel was achieved, not on occupying and subduing every corner of France. Let the French govern themselves in everyday life, policing, sanitation, railroads, hospitals, water, roads, schools, and so. Call these matters administration. Of course, such administration continued in the other occupied Western European countries but run by Germans. Read on.

(2) The difference in France was size and location. German staff estimates of the troops needed simply to occupy all of France were considerable, let alone what would be necessary to subdue continued resistance in a rear-guard or guerrilla action in the Vosges, Alps, Pyrenees, Massif central mountains or the swamps of the Gironde, Loire, Rhone, and Saone rivers. It was best to make peace so that France could be used as a platform against Britain, and as a resource of food, men, and armaments. As it was the German army of occupation in France numbered a mere 40,000 for a population of 45 million, and most of those Germans were concentrated along the North coast opposite Britain. When resistance attacks began, that number increased and the overall calculus changed.

(3) The French navy was distributed around the world, though much was in French waters, not all. There were major elements in Africa (Algeria and Senegal), and there were 18,000 French sailors and more than one hundred ships in England in June 1940. Germany did not have the means of using the ships in French waters, i.e., it did not have the seaman and officers to man them, still less did it have a surefire way to recall the fleet from Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific. The best option then was to neutralise it by an agreement with the French government, i.e., the Armistice, to keep the ships out of the hands of Britain which might have the means to use them. Hence the fiction that Vichy was sovereign neutral. If and when Germany needed the ships, they would then be available. The fiction of French sovereignty kept the much of the fleet on ice for several years.

(4) Finally the colonies were a distraction to Germany. It had no means to occupy even those of strategic value, e.g, French Somaliland on the Red Sea, Lebanon and Syria (then French protectorates) with ready access to Middle East oil, or Dakar (Senegal) with its excellent deep water port on the Atlantic. Each would have been useful, respectively, to disrupt the Suez Canal, either secure Iraq oil or disrupt British access to it, and to base submarines in the Atlantic. Even so, Germany did not have the means (at the time) to do anything about them. Neutrality would be the best, immediate result to keep them out of British hands while the final battle for Britain occurred and allow for the possibility that later Germany would make use of them, brushing Vichy aside.

However, when Hitler turned east to the Soviet Union, then the demands on France changed, and would change again when the Allies landed in North Africa, expelled Germany from Tunisia, invaded Italy and drove it out of the war, and landed at Normandy. Each time, the German bear-hug on France tightened.

The 1940 Armistice allowed France, alone among the conquered European countries to retain a sovereign government beyond the daily administration alluded to above. France was divided into two zones and Vichy had about 30-40% of the country by either area or population. While much of France’s industry was in Paris and the north, Michelin tires, for example, was located within Vichy and several large manufacturers were in Marseilles and Toulon. The Armistice implied that once the war was won against Britain, the Vichy regime would be located in Paris and the northern Occupied Zone would dissolve. Meanwhile, Vichy received ambassadors from the United States and Canada and thirty (30) other countries, negotiated with Britain in Madrid for French assets, sold war matériel to Italy, imported food from Latin America, appointed new governors to its empire abroad … for a time.

Meanwhile, the regime was temporarily housed in the hotels of the spa town of Vichy. Why Vichy? Because nearby Clermont-Ferrand had the very best railway connections and Vichy itself had the most modern telephone exchange in France, connecting it easily to Paris, Berlin, Marseilles, and any where else. Moreover, one the most influential members of the Vichy Regime had major commercial interests there, and probably lobbied for the location, namely Pierre Laval.

By the Armistice, Vichy had administrative responsibly in the Occupied Zone, and near sovereignty in its Free Zone. Indeed, it maintained an Armistice Army of 100,000, unique in conquered Europe. That it existed, motivated many officers and men to be loyal to Vichy until November 1942 when it was disarmed and disbanded.

Though not stated in the Armistice, Paris quickly became a separate, third zone in everything but name.

Paxton convinces this reader that the Vichy regime attempted to use the situation to break with the past of France, and start the National Revolution to wind the cultural clock back. The first break with the past was the name. It called itself L’État Français and not La Républic Français. It repudiated the Republic and all it represented. It was a utopian moment when the discredited past burned away, allowing a Phoenix to rise. And because authority was concentrated in the executive, Pétain and the cabinet, with no carping, criticising parliament to be accommodated, it was a green-fields opportunity to (re)create a society afresh by dictate.

The Vichy Regime was Catholic not secular, agrarian not urban, insular not cosmopolitan. It did not celebrate the Rights of Man but rather the duties of a good Catholic to pray, work the land, procreate, and shun outsiders. On grounds that a religion brings order and calm it embraced Catholicism, though none of the principals of Vichy was ever religious, and certainly not Pétain himself, still less Laval. The school curriculum was changed and the Catholic Church invited to re-enter the classrooms from which it had been expelled after the Revolution. Science was de-emphasized. Curriculum committees set to work cutting French literature down to Vichy-size, big ideas out, duty and humility in. Girls were encouraged to pray and bear children for France. Withal, the author argues that Vichy was not fascist, but rather nationalist, nostalgic, and conservative. For example, its anti-Semitism was culture not racial. Hence the efforts of Vichy, ineffective though they were, to protect converted Jews.

Paxton shows in a great many ways that the Vichy Regime strove to be an active partner with Germany when it seemed that Germany’s final victory was only a matter weeks away. Again and again, Vichy took the initiative to expel Spanish Republican refugees, to identify foreign Jews, to surrender arms, to bomb Gibraltar, to turn over information, to oppose Britain in word and deed, and to excoriate de Gaulle. Later, by 1944 the tables had turned and Vichy was merely a German catspaw, but that was not the case in 1940, in 1941, in 1942, in most of 1943, and even in some ways in early 1944.

Phillipe Pétain headed the Vichy government, bringing to it little more than his name, as the victor at Verdun in 1917 and a reputation, in contrast to so many in World War I, for saving the lives of his men behind fortifications and not spending them in pointless attacks. He was 84 years old when he took over. German intelligence kept an eye on all things Vichy including Pétain himself, and its assessments repeatedly confirmed that the old man had his wits about him, though he tired easily in the afternoons. We should all be so fit at that age.

When the time came the Vichy regime made itself a German catspaw. To make work in the South it negotiated contracts for war matériel for Germany. When Germany demanded slave labour, Vichy conscripted it. When Germans retaliated for resistance attacks by shooting hostages, Vichy volunteered to do that, and in some cases exceeded the German appetite for blood, as both local and national authorities settled old scores, personal and political. Most of all it delivered up Jews ever easier. Once on the slippery slope, the only way was down and down into the levels of Hell.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

Frenchmen arresting Frenchmen to please Germans.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

French volunteers against Bolshevism on the Russian Front.

Paxton chronicles the infighting, careerism, exploitation, profiteering, undermining, conflicting personalities within the hothouse of Vichy, though he offers no explanation for the remarkable dismissal of Pierre Laval in 1941, who bounced back and exacted revenge on his real and imagined enemies. The seamy side of Vichy is well realised in some of J. Robert Janes’s krimies set in this time and place like ‘Flykiller’ (2002).

One of the claims of Vichy was stability. Unlike the volatile Third Republic where governments lasted six months at best, and often less, Vichy would be a rock, as Pétain was at Verdun. Vichy propaganda repeated that claim untinged by the fact that its was a government set to musical chairs with six ministers of defence in one year, and a parade of prime ministers (until the Germans put a stop to it): Pétain, Weygand, Laval, Flandin, Darlan, and Laval again in less than 2 1/2 years. The Third Republic had longer periods of ministerial stability than Vichy ever had. Rather reminded me of the Murdoch media where what matters is repetition not veracity. Pétain wanted to remain prime minister and tried to regain that post but lost in these manoeuvres Laval.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

Pétain and Laval. They despised one another but were bound together in a bargain with the Devil in Berlin.

This book also makes very clear just how very alone Charles de Gaulle was on the 18th of June 1940 in London and how alone he remained for quite a time, making his creation France Libre all the more remarkable. De Gaulle remained alone because the chain of command in the army and the colonies held, despite the catastrophes of the defeat, the surrender, the occupation, the dismemberment.

There are honorable exceptions to the unalloyed vanity, venality, and immorality of Vichy. General Charles-Léon Huntziger, whom Charles de Gaulle specifically invited to command Free France forces, chose to stay at his post to share the fate of his soldiers in captivity, signed the Armistice in that railway car, and then worked tirelessly on the Armistice Commission to secure the release of French prisoners of war by any and every means, and met with some success.

To end where we started with ‘Casablanca,’ the Governor-General of French Morocco, Hippolyte Noguès, held to Vichy despite his own expressed conviction that the Reynaud government should retreat to Algeria and continue the fight from there. This was soldier who obeyed orders, however distasteful. But when by the terms of the Armistice a German commission arrived to monitor the French troops there, he restricted the movements of its members, assigned them a police escort, insisted they wear civilian clothes, put them in poor accommodation, and tried everything within his limited powers to minimize their impact. ‘Casablanca’s’ Major Strasser would not have been allowed to wear his uniform, click his heels, drive around with a Wehrmacht guard, or start a bar fight. Not quite as accommodating as Louie Renault in the film. On the other hand, in 1942 when he was told, the day before, that American forces would land, he was ordered to resist, and he did for three days before surrendering. Not quite the romp show in ‘Patton’ (1970).

The book is informative, insightful, meticulous in the use of evidence, precise in drawing conclusions, and makes extensive us of German archives. It is also somewhat repetitive, which suggests more organisation is necessary, and there are annoying lapses in composition. Too many sentences end with ‘however,’ ‘moreover,’ and ‘of course.’ Far too many. There are also cryptic references to French history better suited to the seminar room. The author compiles some compelling data, especially in the final chapters, that is, quantitative, calories a day, total costs, tonnage of shipments, and the like, and these are presented as lists in paragraphs. While the presentation of evidence is welcome, this method detracts and distracts. Better to have presented as much of this evidence as possible in charts, graphs, and tables to give the reader a picture to put the detail into perspective.

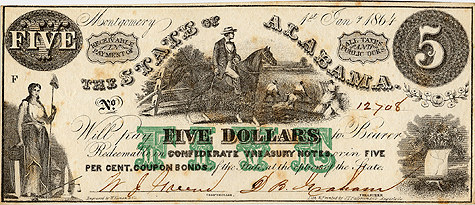

Postage stamp catalogues feature stamps printed but not distributed by the Vichy regime for France’s far flung colonial empire. By early 1943 Vichy had lost contact with most of that empire, apart from North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco), and by 1944 all of that empire had gone over to Free France, with the exception of Indochina which the Japanese had occupied much earlier, despite the protests of Vichy. Germany made no effort to discourage this Japanese strategic move. Yet the stamps kept coming off the presses.

In a time of desperate shortages, when skilled manpower was at a premium, when printing presses were being broken up to be re-fashioned into weapons, when oil was a rarity, at this time the Vichy government had printed by the thousands in Paris those postage stamps for all of its lost empire. Almost none of those stamps were ever issued, that is, they not transported to Madagascar, Réunion, Nouvelle Caledonie, St Pierre et Miquelon, Guyana, or the Antarctic station. An example suffices. New stamps for St Pierre et Miquelon were issued six months after those strategic islands off the Atlantic coast of Canada had been occupied by an Anglo-Free France force. Reality did not intrude into the process, once engaged. Anyone who has worked for a larger organisation knows the truth of that fact.

Issued in 1943

Issued in 1943

Is this a case of bureaucracy gone mad? With the new constitution of Vichy the colonies had to have new stamps, so new stamps were produced regardless of the circumstances. Possibly. Another explanation presents itself, though, continuing to make work like this shields the workers from conscription for slave labor in Germany. The stamp designers, the stockmen, the inkers, the suppliers of ink, paper, and glue, the auditors all become essential workers in the Vichy administration. With this make-work perhaps some Frenchmen were protected from the dreaded Service de Travail Obligatoire.

‘Particle Fever’ (2014)

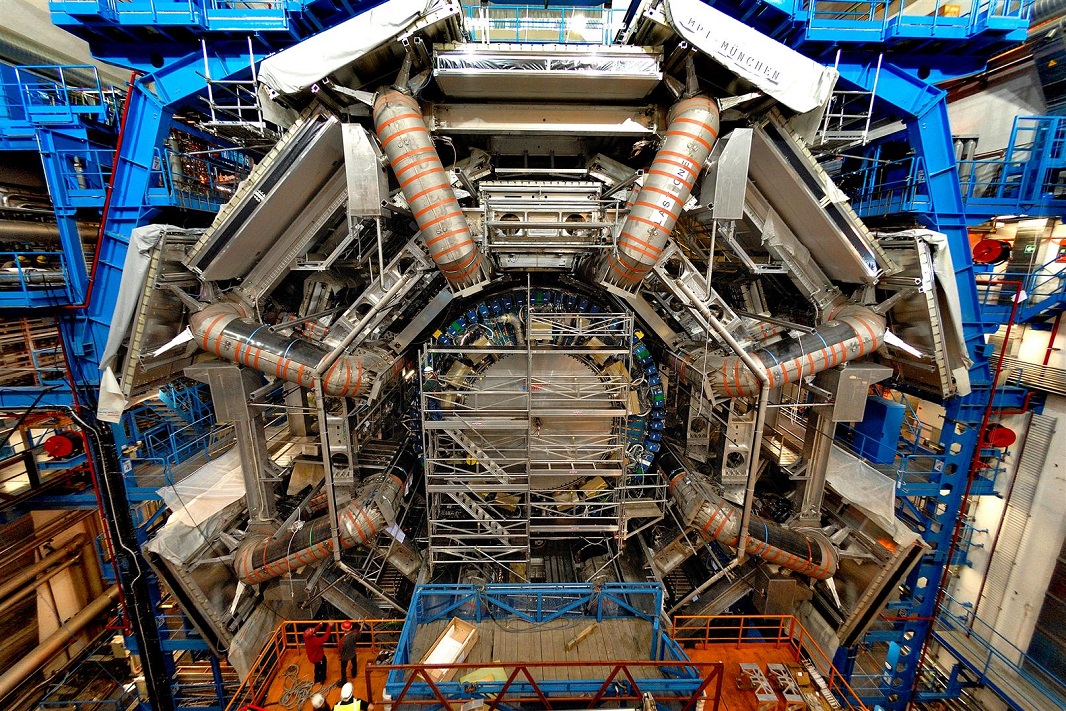

Driven by the pack instinct of nerds, we went to the Dendy Newtown to watch ‘Particle Fever’ about physics. The star of the show was the Large Hadron Collider at CERN (Centre Européenne pour la Recherche Nucléaire) in Geneva.

The focus of the 100 minutes was the alternative explanations offered by theoretical and experimental physicists. The commitment of the individuals portrayed to pursuing ideas and testing them was inspirational. All the more so, considering the diversity of their background and formative experiences.

The theoretical issues were well enough explained to keep interest. The mix of interviews, exposition, graphics, background, and images of that Collider kept us engaged. Though much of it was in the form of extended selfies, and that got thin. A super nerd talking to an iPad camera is not entirely captivating.

The search for evidence of the Higgs Boson particle provides the drama, and there is a lot of it, including a meltdown. That Peter Higgs is there to see it was touching, affirming, and delightful.

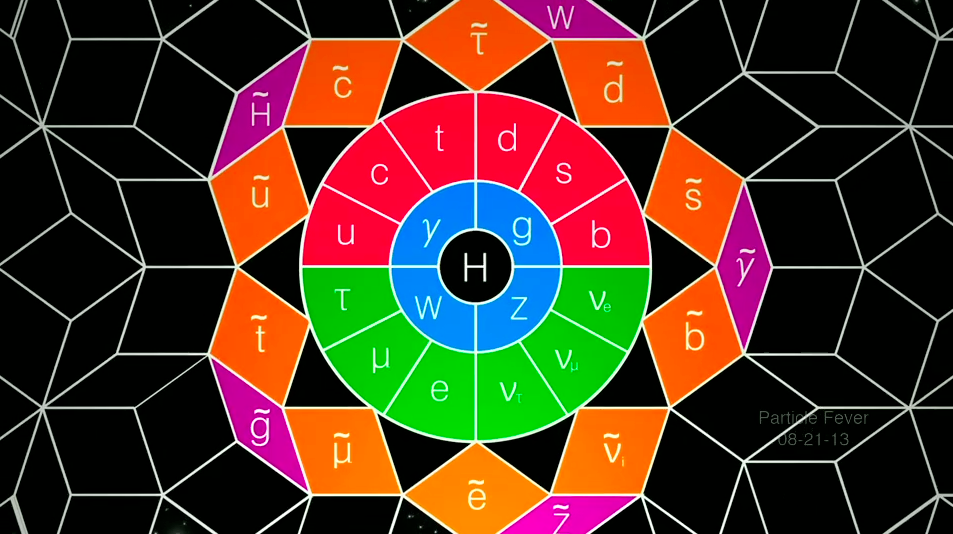

The theoretical matrix in which Higgs Boson is crucial

The theoretical matrix in which Higgs Boson is crucial

Along the way are messages about the importance of basic research which everyone wants and no one wants to fund. The clips of United States congressmen defaming such research is sobering, though the conditions of unfettered thinking that physicists at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton enjoy is the obvious counterpoint which left in silence.

Also left in silence is the engineering that built that sucker, and the endless political work that must have gone into securing, maintaining, retaining, perpetuating, and using its funding.

Look closely at the people in the bottom left for perspective

Look closely at the people in the bottom left for perspective

This is a film about the actors on the stage, the physicists, and not about the stage machinery that made it happens. More’s the pity, because the people who made it happen also include all the politicos who sold the project, and continually re-sold it to keep those Euros flowing.

My visit to Geneva years ago took me to the League of Nations archives where I read 3×5 index cards from 1939. Now I know what I missed!

‘Softly dust the corpse’ (1960) by S. H. Courtier. Recommended

A fine krimie by an Australian writer, this and his other books too long out of print. This one was originally published in London as ‘Gently dust the corpse.’ Why it was changed from ‘Gently’ to ‘Softly’ is anyone’s guess.

It offers the classic setup of an group people isolated from the outside world with tensions among them, in this case at Tyson’s Bend on the Old(est) Hume Highway between Melbourne and Sydney near Mildura in the 1950s. The tensions spring from a missing lottery ticket worth £100,000. So far so ordinary.

Tyson’s Bend has a petrol pump, a general store, a pub, a school, and perhaps a population of 200.

What sets this work apart is the additional character of the dust storm that cuts cuts off Tyson’s Bend from the outside world, making driving impossible and bringing down telephone wires. While most of the townfolk shelter at home about a dozen take refuge in the pub where, thanks to a generator, the beer remains cold. These people are the syndicate that bought the lottery ticket which has won, but before they can collect the dust storm hits, hits hard, and keeps hitting.

The wind howls and cracks, the dust is invidious and insidious, getting through every crack, slit, hole, and into everything from eyes to drinks. It just goes on and on, shaking the roof, ripping doors open, cracking windows, overturning cars, blowing detritus with force, making a walk from one house to another as dangerous and difficult as such a walk in an Antarctic winter. Even in the pub, dust swirls in the air and coats and re-coats every surface. Makeshift face masks and dark glasses are essential to venturing outside and they add to the mystery.

The dust of the Red Centre

The dust of the Red Centre